Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:23 — 29.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

By 1955 the sport of endurance riding had existed in America for more than 40 years since the initial competitive 1913 ride in Vermont. The sport was called “endurance riding” by those who participated in it for the early decades. Part 2 will cover the very significant birth of the famed Western States Trail Ride (aka Tevis Cup), which inherited practices from the older endurance rides, especially the Vermont 100 Trail Ride.

Introduction: Different Formats For Endurance Rides

About 1970, a redefinition was invented to solve disputes of competing endurance riding factions. The main difference is whether an endurance ride should enforce a minimum finish time to protect the horse. It appears that much of what was called in the past, “endurance riding,” wasn’t really endurance riding, it was “competitive trail riding” simply because they had a different format and distance. To this outsider history buff, you shouldn’t rename the past to fit your format preference of the present. Nevertheless, most of those who prefer the present-day “endurance riding” definition believe that their sport gave birth in 1955 with not much acknowledgment of the past. That “birth” will be covered in this part.

The parallel with ultrarunning history is fascinating. Many runners think incorrectly that the entire ultrarunning sport was born with the creation of the Western States Endurance Run in 1977. Similarly, many riders think that the entire endurance riding sport was born with the creation of the Western States Trail Ride. In both cases the legend and folklore of these major events are taking too much credit at the expense of pushing aside their heritage and those who made their events possible to be established.

The creation of the Western States Trail Ride was certainly a pivotable historic event for the sport. It would eventually lead to the creation of the American Endurance Ride Conference (AERC) governing organization in 1971 that helped launch the endurance riding sport into a new modern era. Even more impactful to the endurance world was the creation of the Western States Endurance Run in 1977. Both of those events will be covered in the next article/episode.

The State of Endurance Rides in 1955

In the 1950s and 1960s there was no overarching governing body for endurance rides to set standards or to sanction the events. Much like trail ultrarunning today, riding competitions were created by independent associations and clubs. Event directors could set the distances and rules themselves. Public perception and criticism influenced how the events were handled. Rides were created patterned after other rides held in the country. But the endurance riding sport did exist before 1955 and was growing.

In 1955, the premier endurance ride, the Green Mountain 100 Mile Trail Ride, held its 20th annual ride and was alive and well. Miss USA presented the Ride awards in South Woodstock Vermont. Also, the 5th annual Florida 100 was conducted that year by the Florida Horsemen’s Association in the Ocala National Forest near Umatilla, Florida. It was a three-day event using a well-established endurance riding standard, used by other 100-mile rides, of 40-40-20 miles for three days. That year, 28 riders participated. There were many other endurance rides that year including a 100-mile ride that was held in the Sierra Nevada and it didn’t go to Auburn. It was the three-day Washoe Junior Horseman 100-Mile Ride. Youth riders were accompanied by adults who performed the duty that ultrarunners call “pacing.”

The 1955 Planning Meeting in Auburn

Legendary Wendell Robie (1895-1984) was at this meeting and was the person who brought forward a proposal for a one-day ride. He was a well-known businessman and outdoorsman in Auburn, California where he helped establish winter sports in the Sierra. He was currently serving as the vice-chairman of the State Board of Forestry.

At this historic 1955 meeting, there were concerns if a one-day, 100-mile event was practical and possible. The majority of riders thought it was a crazy idea. Robie was a very vocal participant in the discussion. The Auburn Journal reported that at the meeting it was discussed that “old time horsemen on fairly frequent occasions were known to have ridden 100 miles or more in a day’s time on one horse. Several horsemen were present who reported having ridden 72 to 86 miles to a day’s destination and in their opinion the added miles for 100 miles would not have been detrimental to their horse or themselves. Dr. Bullock, [vet] reported it would be a long ride but probably well within the capacity of present-day horses properly conditioned for it.”

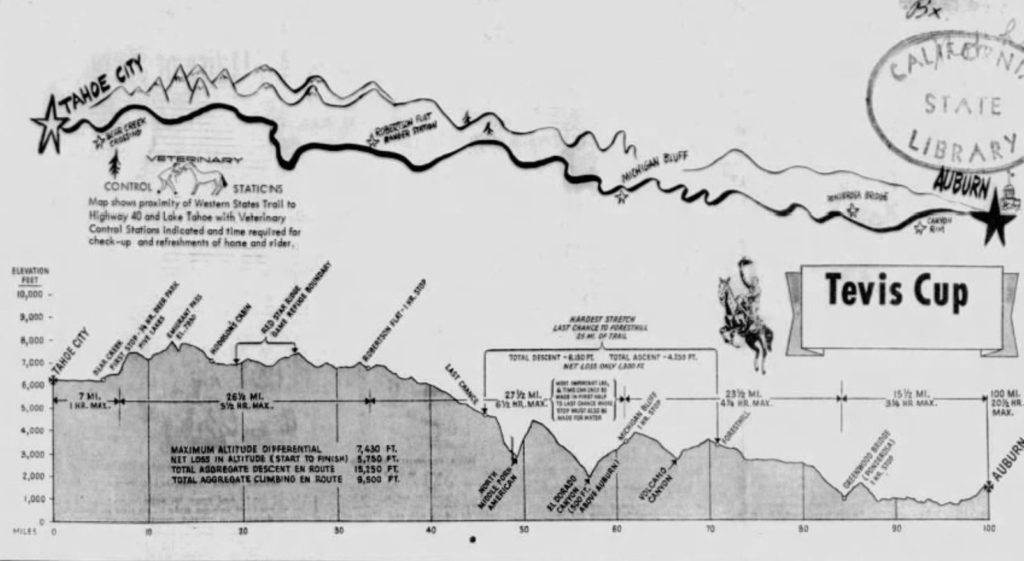

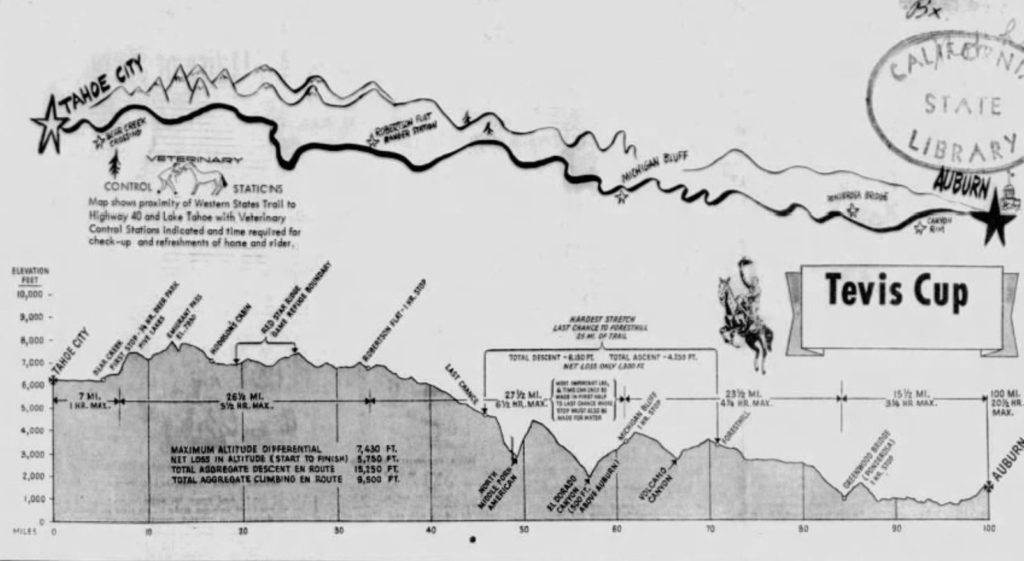

The trail to be used was discussed and it was called at that time the “Auburn-Lake Tahoe Riding Trail.” About the trail, the Auburn Journal stated, “Horsemen familiar with the route claim it is the best riding trail to cross the Sierra which is left with natural surroundings and without paved roads and automobiles.”

For the 100-mile one-day event it was proposed that this ride use the same “strict veterinarian qualifications and similar endurance contest rules to those developed for the Green Mountain Trail Ride in Vermont and similar well-known established endurance races.” Robie later held up the Vermont Ride and its organizers as proof that Endurance Rides were fine for both riders and horses. Thus, it is historically important to understand that the establishment of the birth of the Western States Trail Ride had important roots from the well-established, existing Endurance Rides of that time. It is also totally historically inaccurate to state that the organizers of the Western States Endurance Ride invented the sport. A follow-on planning meeting for the event was scheduled for January 31, 1955.

After this initial meeting Robie was enthusiastic about this event and went into action to help. He developed a prospectus under the name of the of the “Lake Tahoe-Auburn Trail Ride Committee” with an address of Auburn’s City Hall and provided some financing.

In April, organizers presented at the Placer County Chamber of Commerce meeting. They distributed maps of the “Emigrant Trail” and it was mentioned that Wendell Robie was backing the ride which would attract about 250 horsemen for the different types of rides. Those at the meeting “agreed it was quite an undertaking and would, if successful, go a long way to establish a worthy annual project.”

Western States Folklore

As with most important historical events, legend and folklore grew out of the birth of the Western States Trail Ride. The same thing would happen after the Western States Endurance Run was established many years later. Folklore can take on a life it its own as it is told and retold. One well-established story states that during 1955, Robie had a discussion in a bar with an associate about whether a horseback rider could cover 100 miles in a day. He got riled up about it, vowed to prove it could be done, accepted a wager, and just did it one day with four friends. Perhaps he did have such a discussion, but the ride was put in place as part of a well-planned event involving three riding clubs.

Contemporary newspapers called Robie, “one of the organizers” of the ride, not the founder. But as Robie’s legend grew, he was mistakenly given all the credit for organizing the first Ride and later called “the founder.” The truth is that there were many forgotten individuals who organized the event. In 1955 Robie was not the chairman of the event. But there is little doubt that he was the main individual who pushed for the one-day 100-mile event and helped make it happen. He also was the driving force to keep it going.

The Trail

There is also a lot of folklore surrounding what would be called the “Western States Trail.” The WSER website states erroneously that the trail extends all the way from Salt Lake City, Utah. It does not and never did. Some stories state that the trail was used by the 1860-61 Pony Express riders. It was not. The Pony Express Trail went on the other side of Lake Tahoe and didn’t go to Auburn. Some stories say that Robie did historical research and discovered the trail. He did not.

A significant character in the Western States history has been mostly forgotten. During early 1930, Robert Montgomery Watson (1854-1932), a Lake Tahoe lawman, located and mapped out an old emigrant/miner road that was used before the railroad arrived. He also constructed the granite monument near Emigrant Pass. The trail was used by emigrants, many heading to the California gold mines and by miners traveling to and from Nevada. Over the years, this trail would be used frequently by horsemen. In 1956 Robie would rename this well-established “Auburn-Lake Tahoe Riding Trail” to the “Western States Trail” and pretty much adopt it as his trail.

The 1931 Ride

The main purpose of the 1931 ride was to place markers on the trail so it could easily be used by riders in the years to come. The riders started in Auburn and on the first night camped at Michigan Bluff after about 36 miles. It rained during the night. On the second night they camped at Robertson Flat where Watson, age 77, joined the company. Robie considered Watson as a mentor and said of him, “He was a man of destiny, a man before his time, and man who could live astride a horse. Watson broke the first trail for endurance riders.”

They took a day and a half more to ride from Robertson Flat to Tahoe City with Watson guiding them. The route was rough, at times “no more than an opening through the tall pines, over and around huge boulders and narrow ledges.” On a very steep section near French Meadows, a pack horse lost its footing, fell and rolled down into a canyon. Patrick went down, secured a long rope on the troubled horse, attached it to his saddle horse and “pulled the shaken horse back up to the trail without losing supplies or injuring the animal.”

They spent the last night camped at Needle Peak and the next day rode slowly up to Squaw Peak. Watson placed an American flag on the monument. Robie’s wife and other women had ridden up to ride the last miles with them. Watson later said, “The trail is marked so clearly that parties desiring to retrace the steps of the hardy pioneers would have no difficulty in following it from Auburn to the lake.” Robie commented that it was a beautiful trip and “presents some of the most naturally wonderful views in California.”

When the weary riders arrived at Tahoe City after three and a half days, they were greeted by a large crowd. Lukens was very stiff and sore and had to be helped dismounting by rolling up a bale of hay for him to step off onto. The crowd roared in laughter. Shields reported that the men had spent 39 hours in the saddle. He said, “The trail was completely obliterated by brush and boughs and we had to search out the trail at many points to keep the horses going the right direction.”

The men announced that were making plans to hold an annual summer tourist trip from Auburn to Tahoe City on the trail. Lukens explained, “It’s a trail of thrills. It will make one of the most fascination trips in the world. With a little work it can be made perfectly safe for guiding large parties back and forth from Auburn to Tahoe.” They had a vision of camps located at French Meadows, Robinson Flat, and Michigan Bluff. Their plans didn’t take hold, but the trip had a deep impact on Robie and remained in his mind for years.

The First 1955 Western States Trail Ride

During 1955, Robie worked hard to help organize and advertise the big “Tahoe to Auburn Trail Ride.” He was a master promoter. Lavell Shields was the chairman of the Ride. Shields had also participated in the 1931 ride. The big event was held as planned August 5-7, with more than 100 riders. There were three 100-mile events, a three-day ride (68 riders), a two-day ride (34 riders), and a 24-hour ride (five riders).

On August 7, at 5:20 a.m. the five riders, Wendell Robie (1895-1984) of Auburn, Richard “Dick” Highfill (1921-2009) of Auburn, Lincoln “Nick” Mansfield (1908-1999) of Reno, young Patrick “Pat” Sewell (1938-1978) of Sacramento, and William “Bill” Patrick III (1904-1981) of Sacramento, were ready to start the 24-hour ride at Tahoe City. To honor the spirit of the 1860-61 Pony Express, a history that he loved, Robie carried a mail pouch to be delivered to Auburn. A siren sounded and the riders were off to travel on historic trail. The riders proceeded to Squaw Valley and climbed up the steep, rocky trail to Emigrant Pass.

A newspaper reported, “Robie set a mile-challenging pace at the beginning of the ride with horses travelling at either a show or fast trot. There was very little walking, mostly uphill, and no galloping.”

As they crossed the upper regions of the Middle Fork of the American River, Highfill’s horse slipped on a granite slab and went down, injuring its shoulder. When they arrived at Robinson’s Flat (about mile 33), a veterinarian checked the horse and determined that it couldn’t continue on, so Highfill dropped out. Staff members from the University of California School of Veterinary Medicine examined all of the horses at given points.

The remaining four riders continued on. When the trail became very difficult, they dismounted and led their horses ahead. On sharp inclines they would follow behind, holding their horses’ tails, letting the horse pull them up the slope. Mansfield, the owner of Western Stables in Reno, said, “Wendell was confident, and he had his mind set. He very definitely knew he was going to make it.”

When they arrived at Michigan Bluff (about mile 60) around dusk, the vets declared the horses fit to continue. The other two riders, Sewell and Patrick, were exhausted and had to be coaxed to continue on. Night travel on the ridges was pretty scary. Mansfield said that in the dark he didn’t spend any time looking down because “in places there was too much down on both sides of the trail.”

As the riders rode near “the old Mountain Quarry” at about 3 a.m., they were surprised to meet a young man running on the trail, Harold Jay. “He trotted along nonchalantly in pace with the horses for a mile or so and then shot ahead of them at a fast run, to appear again about an hour later, keeping an easy pace with the horses which were traveling at a mountain jog. It turns out that he was a long-distance runner spending part of the summer in the mountains to get in shape for competition.” Jay, who had no trouble keeping up with them on the rough, dark, trail, said he would run and guide them the rest of the way with a flashlight. He was the first trail runner to run with the horses on the famous trail.

Mansfield and Robie reached the finish ahead of the others. Mansfield invited Wendell to be the first to cross the finish line. They finished at 4:05 a.m. for a total time of 22:45, with about 19 hours in the saddle. The riders had covered the last 40 miles in the dark. Robie handed the mail pouch to a police officer and then rode his horse one more mile to his home on Robie Point. The runner, Jay, asked Mansfield (from Reno) what he was going to do. He replied, “I’m going to lay down in a stable and go to sleep.” Jay insisted that Mansfield go home with him. Mansfield said, “When he showed me to my room, I was dead asleep almost before I could get into bed.”

The 1956 Ride

Wendell Robie kept the ride alive and took it over. He renamed the Auburn-Lake Tahoe Trail to The Western States Trail and organized the Western States Trail Ride Inc. He initially called the ride that year, “The Pony Express Ride.” He knew that the 1960 Winter Olympic Games, that would be held at nearby Squaw Valley, would bring significant attention to the area and he hoped to capitalize on it with the 100-year anniversary of the Pony Express. An editorial criticized Robie with fraud on plans for a 1960 Pony Express 100-year commemoration because the Pony Express never passed through the county or on the Western States Trail. Robie countered that he knew mail was delivered between the mining camps using the trail before the Pony Express was established and felt justified.

That year, in 1956, Nick Mansfield and the Washoe Horsemen’s Association added a 50-mile “Pony Express Ride” leg from Reno to Tahoe City. Riders then changed horses to participate in the Western States Trail Ride for a total of 150 miles in two days. Real mail was carried with the approval of the U.S. Post Office to be delivered to from Reno to Auburn for 15 cents plus postage.

There was a lot of attention that four women signed up for the ride. Concerns were expressed that riders could cheat by changing horses, but it was explained that each horse would be stamped with an ink mark that would be inspected at the finish.

For the 1956 Ride, twenty riders started, including Robie who carried the “Pony Express” mail pouch. The route that year started at Tahoe City, followed the Truckee River to Squaw Valley, climbed to the Emigrant Trail Monument, descended west over ridges and through canyons to Robinson Flat, Michigan Bluff, Spring Garden, on the Ponderosa Way, on the old Gold Rush mining trail, and along the Middle Fork of the American River to Auburn.

One of the 1956 riders, Jack French, rode down in one of the canyons but had to drop out far from a checkpoint. He found a hermit in a cabin back in the hills and spent the night with him. “Jack said it was the most interesting experience of his life. He sat up all night listening to tales of the Old West and the mining boom in that area.” Days later, French and his daughter would go back to take supplies to the hermit and they became close friends. French said he would again ride the next year and planned to spend the night with “the old codger” again to hear his tales.

Two horses died during the race, but apparently Robie tried to keep that quiet but word leaked out. One horse had a heart attack near Deadwood and the other one collapsed from fatigue. The Sand Juan Record wrote, “The one-day 100-mile ride may be abandoned next year because of the fatalities.” A letter to the editor of the Auburn Journal included, “True horse hovers feel that such heartless stunts should be prohibited by laws which surely must be on the statue books to assist the humane societies in protecting dumb animals from the cruelty of brainless or heartless humans. It’s too bad the riders didn’t get their necks broken when their horses collapsed.”

The 1957-1959 Rides

In 1957, the name of the Ride was changed and was very long. Robie still wanted the Pony Express connection. It was called “Western States 100 Miles One Day Pony Express Ride.” Each year the weekend of the ride varied a little to try obtain a full moon for the event. Nineteen riders started. The Reno mayor, Lenonard “Len” Harris (1909-1979) planned to ride that year and left a wakeup call with the hotel clerk for 4:00 a.m. But he didn’t wake up until 7:00 a.m., missing the start at Tahoe City. He hired a helicopter to take him to Squaw Valley in hopes to catch up, but the riders couldn’t be located. He then drove to Foresthill in Robie’s car, again hoping to join the group to at least complete the ride with them. But he was unable to rent or buy a horse so he drove to the finish at Auburn.

Robie finished in 20:25. Two youngsters finished that year, David Jay, age 12 and Gwen Smith, age 13. More than 1,000 real letters were delivered to Auburn. To determine total elapsed time, riders got a postal cancellation at both Tahoe City and Auburn that contained the time.

In 1958, 28 riders started at Tahoe City. Seventeen finished, seven from Nevada and ten from California, including eight women. Robie set a new speed record of 20:20. It leaves to you wonder if anyone dared trying to beat Robie.

Nine of the horses were pulled out of the ride along the way by the vets. A husband and wife both finished, Buck and Marcia Anderson. Robie proclaimed that they were the first husband and wife in the world to finish riding 100 miles in a day.

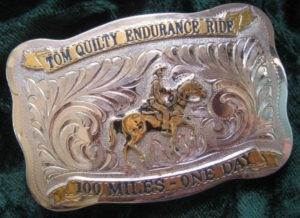

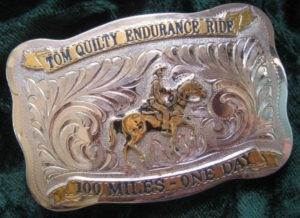

The Tevis Cup

Starting in 1959, the ride also started to be referred to as the “The Tevis Cup” when famed horseman, Will Tevis (1891-1979), a San Francisco businessman, introduced a perpetual trophy that would be awarded to the winner each year. (Or more politically correct “first to finish.”) The trophy was named after his grandfather, Lloyd Tevis (1824-1899), who went to California to join the gold rush in 1849. He later was president of Wells Fargo and Co. from 1872-1892.

Involving Tevis wasn’t just a nice gesture by the Robie. With the Winter Olympics arriving in 1960, it was a calculated marketing strategy to help the Ride get international attention. As Tevis got started marketing, he said the Ride was “the greatest horse epic and yardstick for horsemanship I’ve ever seen. I think it would be a magnificent event for the Olympic Games and if we made it an international event. Maybe we could even invite Russian Cossacks.” He proclaimed that the Ride “is a test where you can judge a man and horse. You can do it without hurting your horse if you’re a real rider I can foresee the day when we’ll have a runoff contest to limit the number of riders in the event.”

The 1959 ride still also included a multi-day pleasure ride and that year it was a six-day or nine-day ”scenic” ride between Reno and Auburn. To pull off the event, the work wasn’t all done by Robie, or even formerly led by him. Martin W. Sword (1909-1967) of Auburn was serving as the chairman of the board of directors for Western States Trail Ride, a board made up of riders from various horsemen associations from Sacramento, Auburn, and Reno.

Entering the 1960s

By 1960, the Tevis Cup was growing up to be a respected endurance ride with 42 starters. The marketing efforts were starting to work. Among the riders registered that year were two famed riders from Austria and Mexico. But it really was still a California/Nevada event. Movie star, Clark Gable was signed up to be one of the judges. A 78-year-old woman finished that year.

With increased attention came more criticism regarding cruelty toward the horses. To combat that, the Ride secured a letter of endorsement from F. W. Koester, formerly the commanding officer of the Remount Service of the U.S. Army. He wrote, “Your ride is well conceived, and is the type of event that needs to be encouraged whenever it can be regulated properly. From many years of experience, I know that 100 miles in 24 hours is well within the capabilities of a good horse that has been thoroughly conditioned and is properly ridden.” The Ride organization made sure that quote was seen in the newspapers.

With more riders, the Ride needed more volunteers. Why not get the Forest Service involved to also generate good will? Robie contacted the Sierra Rangers asking them to serve as guides and observers. Ten wanted to participate and did some serious training.

In order to compete in the Ride, horses had to pass a veterinary physical prior to the start, and at least four other inspection stations at Robinson Flat, Michigan Bluff, Ponderosa Bridge, and the middle fork of the American River. The first three stations included one-hour mandatory stops for rest. Other check-points were eventually established along the way for timers and recorders. In order to win the Tevis Cup, the horse must be “absolutely sound” at the finish, otherwise the Cup was awarded to the next finisher. Sterling Silver belt buckles where awarded those who finished in under 24 hours (total time) with fit horses.

Each year the list of riders grew along with many spectators. The historic town of Michigan Bluff became a “party site” attracting politicians and celebrities. For many years the ride started in Tahoe City on the shoreline of Lake Tahoe. Riders and families would camp out all along the pristine shoreline preparing for the ride.

Other Endurance Rides Being Held

In 1958, seventy-three riders took part in the Vermont Trail Ride and twenty-nine finished. A 50-mile “pleasure” ride was also conducted with 106 riders. Those riders did 20 miles each of the first two days and ten miles that last day. The course in the 1960s for the 100-miler went from South Woodstock, through Reading, Cavendish, and back. The 20-mile loop went through Hartland and back. The cutoff for the two 40-mile loops had been made quicker, 6.5 to 7 hours, and the 20-mile loop from 2.5 to 3 hours. Because of the extreme popularity of this endurance ride, the field was limited to 75 riders. They traveled over hard and soft roads, up steep hills, over rocky stream beds, and down gullies. In 1963, 74 riders and horses participated in the 100-mile ride from about 15 states.

There were many other endurance rides held during the early 1960s.

- In 1960, the Florida 100 conducted their tenth annual ride using the same three-day “cavalry” format as the Vermont Trail Ride. Awards were given in different divisions depending on the weight of the horse.

- A 25-mile endurance ride was held near Palm Springs, California.

- The Arizona State Horsemen’s Association put on a 30-mile endurance ride in 1963 as a trial for a possible 100-mile ride.

- A 60-mile Black Bart Ride was conducted in the mountains near St. Helena, in Northern California.

- A 30-mile-4-hour endurance ride was held in Pennsylvania by the Conewago Trail Riders. They soon added a 50-mile in 6.5 hour ride with no minimum time restriction.

- A 50-mile, one day endurance ride was held from Casa Grande to Phoenix, Arizona. With the warm October weather, the ride was held during the cool night.

- A 100-mile one-day endurance ride was held in Moore, Oklahoma. The winner was a 13-year-old boy who completed the ride in 15 hours of actual riding time.

- A 75-mile endurance ride was conducted in Dodge City Kansas by the Boot Hill Saddle Club and the Kansas Trail Riders Association.

- A 100-mile ride was conducted in Virginia.

- In Oregon a mountain 50-miler in 14 hours was put together on the Skyline Trail in the Mt Jefferson Wilderness.

- In North Carolina the WNC 100-mile Trail Ride started with the three-day format.

These are just a few examples. The Western States Trail Ride was just one of many endurance rides. It wasn’t the premier ride yet, not the only mountain ride, and not the only 100-miles in one day ride. In Phil Gardner’s “How it all began” endurance ride history, he stated incorrectly that during the 1960s, the only endurance ride that existed was the Tevis Cup until Castle Rock 50 appeared, which he also claimed was the first 50-miler. It wasn’t. Perhaps this was true if your world only existed in Northern California, but endurance rides were alive and well across the United States.

Tevis Cup 1961-1969

Unlike other endurance sports in those early years, women were very prominent in these rides and were equal competitors with the men. In 1961, the winner was a woman, Drucilla “Dru” Barner (1914-1979). She set a course record of 16:02, which included 13:02 riding time, subtracting three mandatory one-hour rest stops. The riding times started to be saved as course records for this ride that wasn’t to be called a race.

That year at Michigan Bluff, Wendell Robie’s horse was ruled lame by Dr. Richard Barsaleau (1925-2013). A vet assistant warned Barsaleau, “You don’t pull a horse ridden by Wendell Robie.” But Barsaleau stuck to his guns and initially Wendall was furious, but later admitted that the veterinarian was right. Barsaleau would go on to finish the Ride 14 times.

Charges of Cruelty to Animals

During the 1961 ride, a 15-year-old girl’s horse fell down a 300-foot embankment and died as a result of the injury. A second horse also died during the event. Protests of horse cruelty resulted and the event became better-known outside the rider community. Past presidents of the California State Horsemen’s Association called for an end to the Tevis Cup Trail Ride. They said the ride was “pointless and inhumane, and endangers both horses and riders.”

Robie defended the ride against all critics. “Most persons have no idea of the capabilities of the western horse. He is a working horse, built for stamina, bred for endurance and capable of feats far beyond the ordinary casual riding done today.” Horses did suffer at times and “gave out.” With the heat, horses would collapse at times and vets would need to ride in to administer IVs.

It was argued by critics that the event was obviously a race with silver belt buckle awards given to those who pushed their horses to finish in 24 hours and a cup for the winner. In the 1961 race, the veterinarians were from the University of California at Davis. Because of all the complaints, they withdrew their support.

Robie met with the Humane Society who gave him a list of changes to the race including banning minors. The race bowed to some recommendation. They didn’t ban minors, but added a rule that riders under 16 years old had to be accompanied by a parent or guardian. Additional “sweepers” would be added to aid riders in trouble. A minimum finish time was established of 17 hours total time. You could not finish faster than 17 hours. Because of this restriction it is interesting to consider that for those years, the Tevis Cup did not fit the definition of a modern “endurance ride” for several years. After the last check-point riders were required to walk their horses for 20 minutes before mounting. All of the changes would go by the wayside within a few years after the public out-cry died down.

Robie took on a more personal role in the next ride. The new ride officers were Robie, president, Nick Mansfield vice president, and Drucilla Barner, secretary.

The California State Human Society Associate decided that “on-the-spot” inspections would be needed for the 1962 ride with a “force of experienced humane officers” from various parts of the state. They showed up at veterinary check points. Robie, rather rudely, said, “Let them take a look at these well-conditioned horses and then they can go back to picking up stray dogs and cats.” The officers did show up. The Ride let them have full access and great care was taken that there wouldn’t be any major incidents and there were not any. They reported, “All 25 horses finishing were tired from their exertions, but none was exhausted, those that could not withstand this type of ride having been eliminated.”

Ironically, the winner was disqualified because his horse was judged “lame” at the finish. The second and third place horses finished in a “dead heat.” The horse that was the best condition after the finish was awarded the Tevis Cup.

1963-1969

Getting lost was a problem. In 1963 a rider failed to arrive at the first check station and deputy sheriffs were sent out to search. The rider was eventually found and was hospitalized because of exposure and dehydration.

Starting in 1964 because of the increased number of horses, groups were established for staggered starts, two minutes apart. This bothered the competitive riders who were truly racing because it was difficult to know where they stood. That year they also started to award the Haggin Cup for the horse among the top-ten that finished in the best condition. An inscription on the cup read, “Kindness to animals despite adverse pressure is the mark of a man.”

Robie, age 68, rode again and suffered a serious injury. His 900-pound Arabian gelding named Timour, stepped in a chuckhole and rolled over with Robie beneath. Several riders wanted to stop and help, but he waved them on and said he could make it to Michigan Bluff. He eventually did, but incurred painful back and rib injuries. He was taken to the hospital but luckily avoided any serious injuries.

That year, 1964, a 17-year-old in high school boy, Neil Hutton, of Reno, won the Tevis Cup on an Arabian mare, Salalah in 14:34 riding time, 17:34 total time. There were 53 starters that year but only 29 finishers because of very hot conditions. It was Neil’s third year in the ride. He said, “I feel great, ready to go after a victory again next year.”

Also that year, Nick Mansfield on Buffalo Bill finished their tenth Western States Trail Ride. Nick received his 10th silver buckle and was awarded a special cup for reaching 1,000 miles. Buffalo Bill received a silver brow band. Buffalo Bill was originally purchased for $12.50 after being left in a Reno pasture by an unknown former owner.

In 1965 the 17-hour minimum time was discontinued and the Tevis Cup became a race again, but they still didn’t want to call it a race. The first rider, Eddie Johnson, set a course record of 11:38 riding time. He crossed the finish line in about 15 hours. Western States was starting to be referred to as “the toughest marathon horse ride in the world.” In 1968 a new record of 11:18 riding time was set by Bud Dardi on Pancho.

In 1966 while training with his horse for the Tevis Cup, Hank Gibbons of Mt. Pleasant, California found the wreckage of a crashed Navy airplane with three aboard that had crashed six month earlier. Bud Dardi won the Tevis Cup that year with 12:26 riding time. In 1967 Ed Johnson won. He was just four minutes shy of the course record, finishing in 11:42 riding time. Robie, age 72 finished to loud applause in ninth place out of 55 finishers with 15:10. Sadly in 1968 two horses became ill with colic after they finished and died at the fairgrounds while be tended by veterinarians.

Ride Details

Over the years, only about half of the riders finished each year. There are various reasons: 1. Going out too fast, getting caught up into the racing aspect. 2. Going too slow and missing cutoffs. 3. Not enough night-riding experience. 4. Not enough rider or crew experience. 5. Horse or rider not fit enough. 6. Various accidents. Those who succeeded the best, participated in previous rides in a crew, or as a volunteer.

The American River crossing was challenging at times. “We had to cross the American River which was so deep in spots that if you missed the ford markings you would have to swim.” Many riders trained on the course so their horse was familiar with the course. One rider mentioned, “When Dolly and I reached a spot near the end of the trail which we had ridden before, she knew she was going home. It was almost like she was smelling the oats. She really whipped out of there.”

Robie in 1965 ride

Crewing was quite challenging. The road to Robinson Flat was not paved and water had to be obtained from a small creek flowing through a nearby meadow. Feeding the horses was fairly easy. Most feasted on hay or grazed. Riders didn’t yet wear helmets and didn’t understand the need for electrolytes. Many had a Western look wearing jeans and cowboy boots and hats. They were given bag lunches for the ride and provided a hot meal served at Bonnie’s Stone Cellar in Michigan Bluff.

The Tom Quilty Gold Cup

Just as Robie signed up Will Tevis to endorse the Western States Trail Ride, Reginald Williams, the ride founder (1908-2003) asked 79-year-old Tom Quilty (1887-1979), a famous Australian horseman, to be part of the ride. Quilty donated the funds for a perpetual trophy, just as Tevis did, and the emerging ride was named the Tom Quilty Gold Cup and a Quilty buckle created.

There was a lot of opposition from animal rights groups. A.J. Croft, the president of the Ride committee wrote a long editor the Sydney newspaper. “The endurance ride is not a race but will be a series of trials to test the endurance capabilities of the horses. I repeat this is not a race. The prize money and cup are in effect an award for the hours of effort and expense which have gone into the preparation of horses.”

A 50-mile trial ride was first held just one month later in May 1966, and then on October 1, 1966 at 1:11 a.m., the 100-miler was conducted with 26 starters, 16 of them women. Rain, mud, and confusion marred the start. Race organizer, Williams, withdrew $1,000 prize money after police called and said they were “not in favor of the race.” Williams said he had legal advice that the contestants should not be riding for any monetary gain.

The course was on “ordinary dirt roads” but had some mountain climbs. Three checkpoints were used and miles 40, 60 and 85. There were only seven finishers, most of the reasons for not finishing were related to the lack of endurance by the rider. Gabriel Strecher, born in Hungary, won with 11:24 riding time. The ride continued to be held annually.

The Virginia City 100

In 1968 a one-day 100-mile ride was established in Nevada that was at first named, “The Annual Nevada All-State Trail Ride.” For the first year, the ride started and finished at the “102 Ranch,” east of Sparks, Nevada. It was later moved and renamed to the Virginia City 100. This ride was the first American 100-mile endurance ride to pattern the event closely after the Western States Trail Ride. This giant loop ride included some significant climbs on rough trails and awarded belt buckles to those who finished in 24 hours or less. The first year there were 33 starters and 11 buckle finishers. Shannon Yewell Weil and Cliff Lewis finished in 19:41 total time. Three of those hours were mandatory vet holds.

Moving into the 1970s

By 1970, the 16th annual Western States Trail Ride was very popular and included international entries. That year there were 200 entries and 169 passed the pre-ride veterinarian tests, declared as physically fit for the ride. That year the start was moved to Squaw Valley because development over the years at the lake had greatly reduced the amount of open space there to accommodate the start area. The move cut out seven miles of the course, a Duncan Canyon Trail section was added before Robinson Flat to help compensate. Riders could spend the night before the ride at the 1960 Olympic Village dorms that had fallen into disrepair.

Ninety-three finished in 1970 within 24 hours and received 100-mile belt buckles. Some officials that year occasionally called the event a “race” which was considered “taboo.” Regardless of what it was called, it was a race.

Donna Fitzgerald won (first to finish) with a riding time of 11:49 despite a bad mishap. While galloping down narrow switchbacks, her horse Witezarif fell of the trail. Donna jumped off safely and pulled him back on the trail. As he got back on, he ran by her, kicked her, and then waited for her down the trail.

One bothersome incident occurred in the American River Canyon near Auburn. A band of “hippies” tried to prevent several riders from crossing the old railroad bridge. Sheriff deputies eventually cleared the area but it cost some riders long delays. At Michigan Bluff the crowd was huge, with about 500 people including “sweaty, beer-drinking horse buffs” who breathed down the necks of the veterinarians trying to do their jobs. That year amateur shortwave radio operators were stationed at key points along the course for emergencies.

As the 1970s arrived, the Tevis Cup had entered the “big-time” and was receiving international recognition as the premier endurance ride in the world. Rides were starting to be established that used the same format. Growing pains and continued public concerns needed to be addressed in the sport. Stay tuned for the next part that will tell the story of the birth of the Western States Endurance Run and the Old Dominion 100.

Continued in Part 3 (1971-1979)

Sources:

- Bill G. Wilson, Challenging The Mountains: The Life and Times of Wendell T. Robie

- Lori Oleso, Endurance…Years Gone By

- Tom Bache, “The Origins of American Endurance Riding”

- “Sixty Years of the Tevis Cup Ride Dusty Memories of Trotting Through the Decades”

- https://www.aerc.org

- http://www.teviscup.org

- https://equusmagazine.com

- https://www.wser.org

- http://www.nastr.org

- http://tomquilty.com.au

- 2017 interview with rider, Hal Hall, 30-time finisher and past member of the Western States Trail Foundation.

- 2017 interview with rider, Rho Baily, past member of Board of Governors for the Tevis Cup.

- 2017 interview with Shannon Yewell Weil, co-founder of Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run and Trustee for 30 years.

- Auburn Journal, Sep 24, 1931, Jan 27, 1955, Aug 23,28, Sep 27, 1956, Aug 8,15, 1957, Aug 13, 1959, Jul 16, 1959, Jul 14, 1960, June 15, 1961, Aug 30, 1962, Jul 30, 1964, Aug 15, 1968, Aug 20, 1970

- The Placer Herald (Rocklin, CA) Oct 3, 1931, Aug 16, 1956, Jul 12, 1962, Jul 31, 1964, Jul 16, 1967

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, CA), Jan 27, 1955

- The Orlando Sentinel, Mar 18, 1955

- Reno Gazette-Journal, Aug 17, 1956, Jul 27, Nov 11, 1961

- The Bridgeport Telegram (Bridgeport, Conn), Sept 6, 1955

- Nevada State Journal, Aug 14, 1955, Jul 7, 1957

- The San Francisco Examiner, Sep 13, 1959

- The Tampa Tribune, Mar 24, 1960

- Oakland Tribune, May 28, 1961

- The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA), Mar 23, 1962

- Casa Grande Dispatch (Arizona), Sep 19, 1962

- The District (Moline, Ill), Sep 22, 1962

- The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Mass), Aug 23, 1963

- Albany Democrat-Herald (Oregon), Aug 3, 1964

- Lincoln News Messenger (California), Jun 23, 1966

- The Sydney Morning Herald, Sep11-12, Oct 2, 1966

- Mark McLauglin, Tahoe Weekly, June 26, 2013