Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:53 — 36.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

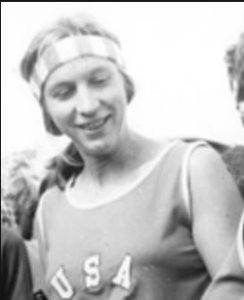

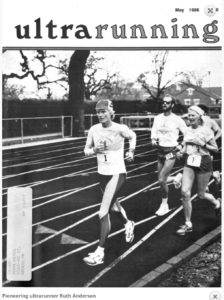

She was a nuclear chemist and began running at all distances, especially marathons, in her 40s. Thus, all of her many running accomplishments, including world records, were achieved as a masters runner. She became an icon and inspiration in the Northern California running community where she was probably its most prolific runner in local races.

But her greatest impact on the sport was made behind the scenes. She aggressively worked hard to open up the doors for women and masters runners to compete in long distance running. The famed ultramarathon London to Brighton race was opened up to women in the 1970s largely because of her persistent lobbying. The women’s masters division was established in running because she wouldn’t accept “no” as an answer. She strived to tear down decades of bias and false beliefs about women and their capability participating in the sport. Ultrarunning legend, Ann Trason said, “I don’t think the sport would be where it is today without Ruth. She was a very fair, generous and kind person who you could really share the love of running with.”

Ruth Frances Purney (1929-2016) was born in Omaha Nebraska, in 1929. She was raised in Nebraska by highly educated and professional parents.

Ruth’s father, Dr. James Francis Purney (1892-1970), was also born in Nebraska. He finished dental school about 1917 and served in the dental corps during World War I. In his professional career, he was a leader and served as president and secretary for various dental associations. He was also an athlete who played football, golf, tennis, and was a member of the Omaha Tennis Club. Dr. Purney was also very involved in the theater, both acting and directing in the 1920s, 30s and 40s. In 1928 he was the director for a performance put on in the local playhouse. His assistant director was a young 23-year-old actor who would become very famous, Henry Fonda.

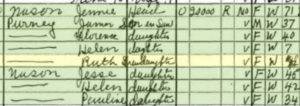

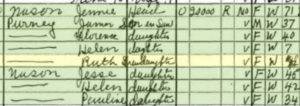

Ruth’s mother was Florence Barney Nason (1890-1952) also of Omaha. Both her parents were graduates of the University of Nebraska. Her mother graduated, in 1915, in Home Economics, specialized in dietetics, and was employed as the head dietitian in a hospital for a time. Her parents were married in 1918. As Ruth grew up, her mother taught home economics at Benson High School in Omaha, Nebraska. During World War II, she was active in the Red Cross, working with the Clarkson Hospital Service League.

Grandparents

To truly understand who Ruth Anderson was, it is also helpful to know who her grandparents were.

Ruth’s father’s parents were Emil Jackson Purney (1854-1894), born in Ohio and Ella Rachel DeLay (1873-1900) born in Illinois. They were married in Denver, Colorado and lived in Wyoming, Nebraska, and Portland, Oregon. Emil Purney, who was called “Cheyenne” by his co-workers was a railroad night switchman who worked for the Northern Pacific. In 1894 at the age of 40, he died suddenly of a heart attack, working in the telegraph operator’s room during the night. “He suddenly complained that his heart was troubling him, and lying down on the floor, expired before medical aid could be summoned.” Ella Purney was left a young widow, age 21 with five very young children including Ruth’s one-year-old father. Sadly, Ellen Purney also died six years later when Ruth’s father was just six years old. He and two of his siblings went to live with their uncle and aunt, Jerry and Mary Scott, in Kearney, Nebraska.

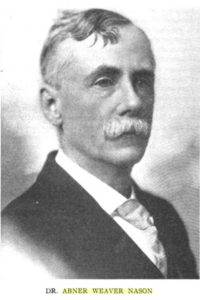

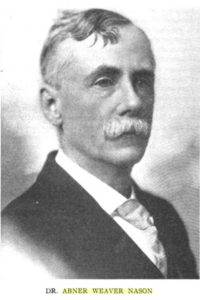

Ruth’s mother’s parents were Abner Weaver Nason (1849-1921) and Jennie V. Barney (1858-

1941), a daughter of a pioneer Omaha merchant. He was born in 1849 in French Creek, New York and became a dentist. He began his practice in 1869 in Mt. Carroll, Illinois and moved to Omaha in 1874 “where for nearly half a century he was recognized as a leader in his profession” and for many years he was dean of the Omaha Dental College associated with Creighton university. “Few members of the dental profession in the Middle Western were as widely and favorably known through the country as Nason. He was always an energetic and progressive leader in the various dental and civic activities.” He was also a member of an athletic club in Omaha.

When Ruth’s parents were married they went to live with the Nason’s, her mother’s parents.

Childhood and Schooling

With upper class parents, Ruth attended Brownell Hall boarding school for girls for both elementary school and high school. It was an Episcopal school in Omaha, Nebraska. At age 13, in 1943, during World War II, she learned photography and won an award in a Nebraska-Western Iowa regional exhibition of High school wartime art.

Ruth said that when she was growing up in Omaha, girls were not encouraged to play sports. But she was very athletic and during the 1945-46 school year served as vice-president of the Brownell Hall athletic association. She followed in the footsteps of her father and played tennis. She said, “Since tennis was somewhat acceptable, I took that up.”

She said no one pushed her on to be truly successful. But she was successful and played for more than seven years (1947-1955), in various city tournaments, and won in both singles and doubles. In high school she lettered in tennis, basketball, field hockey and volleyball. She never thought about running. What fun would that be?

Ruth attended Stanford University in 1950, and received a Bachelor’s degree in Chemistry in 1951 from the University of Nebraska. In college her outside interests were tennis, swimming, horsemanship, as well as music and art. In 1951 she was one 16 “Princesses of the Realm” from the Omaha and Council Bluffs area.

In 1953 Ruth was married to John Thomas Anderson (1928-2016), a graduate of Western Military Academy in Illinois, and the University of Nebraska. He became a veterinarian. He was the nephew of Lewis R. Anderson, a member of the Lincoln Journal’s Nebraska Sports Hall of Fame, as the first athlete from Nebraska to run in the Olympics (1500 meters) in 1912. The couple moved to Lincoln, Nebraska in about 1955 where Ruth continued to compete in tennis.

Oakland California

In 1962, the Andersons moved to Oakland, California where Ruth worked as a nuclear chemist and gamma-ray spectrometrist at Lawrence Radiation Laboratory located in the Berkeley Hills near Berkeley, California, overlooking the main campus of the University of California, Berkeley.

In 1964, Anderson gave birth to her daughter, Rachel Edith Anderson. The young family lived in a two-story house in Oakland’s woodsy Montclair district. She called their home her “tree house.”

Early Running

Anderson started to run in 1972 when she was 43. She would swim in the employee pool, but the heating broke and she looked for other exercise opportunities. She said, “At noon each day a group of fellow workers at Lawrence Radiation Lab in Berkeley would go jogging. One day they convinced me to join them. I had never run before although I did have stamina from tennis and swimming. I brought a pair of tennis shoes and a jogging suit to work. We ran at an eight-minute-mile pace which is what they were geared to. I completed a mile and a quarter. Afterwards, I thought I’d die. I swore that was not going to be my sport. It left me with a horrible awful taste in my mouth, it was hard.I don’t know why I took to the sport. After the first day it all kind of snowballed.” By early 1973 she started to race two miles, 5Ks and 10Ks.

Fellow runners recalled that she had astonishing stamina rather than remarkable foot speed. She was described as having a unique running style in which “she got her legs under her by throwing them out sideways rather than underneath her body. This probably conserved energy since she did not have to spring up as much as normal runners with each stride.”

Women start running marathons

For the 1971 New York City Marathon, the AAU finally agreed to allow women to participate if they started 10 minutes before the men. Later that year the AAU agreed to allow selected women to run in marathons, subject to approval by the national chairman. Selected women were those who had run in a marathon previously, which made no sense since they weren’t allowed before.

The AAU permitted women to run in the 1972 Boston Marathon, but the AAU Women’s Track and Field Committee, severely out of touch, Stipulated that women should start from a different time OR place than the male athletes. Race Director Will Cloney out-smarted the AAU and simply extended the starting line to the sidewalks, “a different place,” allowing the eight women entrants to start at the same time as the men.

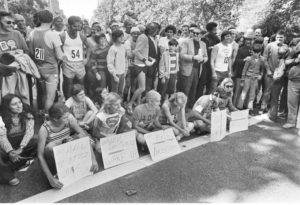

In 1972 the women protested the marthon’s 10 minute delay policy and refused to participate in the special start, sitting down for ten minutes until the men’s gun went off. At the Trail’s End Marathon in Oregon, women were required to provide health certificates and the men were not. The AAU soon removed these practices under the worry of discrimination law suits.

In 1971, Elizabeth Bonner (1952-1998) from West Virginia was the first woman to break three hours with 2:55:22. In 1972 women were allowed to compete officially in the Boston Marathon for the first time. The first all women’s marathon was held in 1973 in Waldniel, Germany.

When Anderson started to run, few women were running long distances and certainly not women over 40 years old. She became a pioneer masters marathoner. Her first marathon was run on September 30, 1973, the Champagne Marathon, in Nampa, California and she finished in 3:52:36 in fourth place. This started a 29-year career running many marathons.

Her future rival and friend, Joan Ullyot, age 33, finished in first place. Ullyot had been working hard to lobby athletic governing organizations to retreat from their archaic view that the sport of long distance running was detrimental to woman’s health. Anderson and Ullyot would run in many races together in the years to come and Anderson also joined the crusade against this discrimination.

Many marathons

Two months later in February 1974, the first AAU women’s marathon championship was held in San Mateo, California. Anderson, age 44, ran a 3:20 lowering her world master’s record. It was written about that event, “This day was perhaps the most important step ever for women’s long distance running, as the fair sex proved to the world that they could handle ‘officially’, the classic marathon distance of 26 miles, 385 yards.” Anderson’s amazing accomplishment gained national attention when the Sport’s Illustrated magazine made mention of it.

In July 1974 she ran in the National AAU Masters Championship Marathon in Portland, Oregon. There was no woman’s masters category or even a women’s category, and officials refused to make one. Anderson ran anyway with the men and finished 11th in a field of 22 with 3;22:45, lowering a world marathon age record. She was the only woman entrant. She said, “I didn’t exist as either a division winner or a national champion for my first place female placing.”

Anderson decided to take on the AAU which she called a “monolithic organization interested only in training Olympic material.” She was instrumental in getting women over 40 to sign and present petitions to the AAU convention in New Orleans. “Women runners are a forgotten minority. We petitioned for a national Master’s division for both men and women and an autonomous long distance running commission for women. We succeeded, so I guess the AAU is finally shaping up.”

1974 Women’s International Marathon Championship

In 1974 Dr. Ernst Van Aaken, a German, and a strong supporter of women’s running, organized the first Women’s International Marathon Championship. It was held in Waldniel, Germany. Forty women from seven countries competed in the event Anderson was one of nine women selected by the AAU to compete and represent the United States. She was thrilled to be included and to go to run in this historic race.

On race-day morning, Anderson and Ullyot nervously jogged together three blocks to the sports hall early to pick up their bib numbers. “An amazing number of people were milling around the start-finish area which was roped off for blocks. Flags of all the participating nations were snapping in the brisk breeze, beautiful to watch.” Crowds of enthusiastic children collected autographs from the runners. Positions on the start line were assigned by number and team rank. The French and the Americans were in the first row.

After the starting gun went off, all the runners seemed to take off in a sprint. Anderson recalled, “It was truly thrilling to run past all the cheering crowds that lined the course.” She ran closely with Anni Pede, the former German national marathon record holder. “We tried to pace each other to a good time to the finish.”

There were two aid stations on each loop, manned by young local runners who would meet the runners before the aid station, ask what they wanted, and then sprint ahead to get it. The volunteers would then run along with the runners while they drank.

The wind was stiff on the long loop course. Ullyot wrote, “Right at the beginning, the disadvantage of the absence of men was clear. There were no large bodies to tuck in behind to shelter us from that headwind. There was plenty of time to enjoy the course, half of it into the wind, but mostly past cheering crowds, the other half on a bike path beside lovely woods, with a view of Waldniel and its church across the fields. We also ran past farms populated by enormous swine. The local photographers loved to shoot views of us running past the sows, for contrast I hoped.”

Anderson was slowed by the wind during the last two laps but pushed on, finished strong with a time of 3:25:32, and won her 40-50 age group among nine contenders. Ullyot wrote, “Ruth Anderson, who had hoped to regain the Masters world record by running 3:17, had been chilled and blown around like a leaf on the last lap.”

To the delight of the spectators, Liane Winter of Germany won with 2:50:31 Many people thought some of the women might die because they held on to the view that long distance running was very dangerous for women. Ullyot wrote, “Red Cross ladies flocked around us dispensing blankets and hot tea. We had to explain to them, however, that we were only tired, not dying. They kept trying to drag us off to the field hospital, while we wanted to stay and watch the others finish.”

The awards ceremony was held in a basketball gymnasium in front of an enthusiastic crowd. Dr. Van Aaken, who had fought so long and hard for acceptance of women into marathons, felt vindicated and was very moved. They partied until 3 a.m. Anderson said, “I was personally left with a feeling of immense gratitude for having been part of all this. Without the encouragement and support of my wonderful husband, John, I would probably never have undertaken such an endeavor in the first place. My hope now is that with this excellent precedent, the Olympic Committee will recognize the need and desire for women to participate in the marathon distance in the Olympic Games. Certainly this is a worthy goal to strive for in 1976.” (Sadly, women didn’t compete in the Olympic Marathon until 1984.)

Running recognition

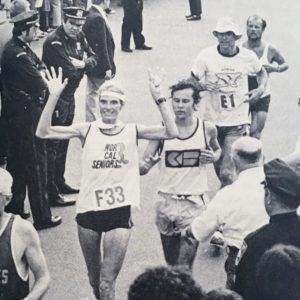

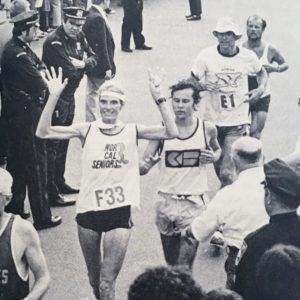

In 1975 Anderson ran in her first Boston Marathon. She was rather surprised with the reception she received from various women runners. She said, “Three years ago, not many women past 40 were running. One of the greatest thrills of my life was when I went to the Boston Marathon. There were many women entered who were over 40 and they couldn’t thank me enough. They said I was an inspiration to my age group.”

Before the race, she attended a women’s meeting and met many of the crusaders and pioneers of women’s long-distance running. Her eyes were opened to just how much inequality and prejudice still remained against women’s long distance running. “The AAU Women’s Track and Field committee still held views that 1500 meters was perhaps even a bit too far for the fragile female athlete.” Those at the meeting were determined to see that a separate long-distance AAU committee be established to better meet their needs. That was established at the end of the year. As for the race, Anderson finished in 24th with 3:25:48.

A newspaper feature wrote, “Ruth Anderson is the kind of person any dues-paying male chauvinist would fear. She’s the antithesis of Edith Bunker, a fully-realized woman over 40 who is having the time of her life. Beside having competed in 57 marathons, she’s a full-time scientist, wife, mother, part-time painter, writer and occasional house-keeper.”

At age 46, she was a great example for the older runner. She said, “So many women past 40 feel put down as if there are no outlets left. But running is an adventure. It’s certainly economical and you can do it no matter how bad the weather. And it’s so beautiful to run through parks, especially when there are deer bouncing in front of you. People ask me how I keep from being bored running for several hours. Well, I fantasize like, maybe I’m in the Olympics.”

With a women’s masters division established because of her efforts, in October 1975 she competed in the AAU Masters Championship Marathon in Medford Oregon and came away with the win in 3:15:47 at the age of 46.

In December 1975, she again lowered her masters world record by running 3:10:10 at the Livermore Marathon in California. She was a celebrity and fixture at so many races of all distances and usually always came away with the masters award.

Ultramarathons

At age 46 in 1976, she ran her first ultra, the Sacramento Guard Highway 50K on a road course, which was also the AAU 50K championship. She came in second place with an impressive 4:17:53. That convinced her that she could continue to achieve high results at ultra distances.

Unfortunately, In September, she had to put running on hold when she broke a bone in her foot while running the Double Dipsea. But she still stayed busy and was appointed the national chairperson for the new Women’s Masters AAU Long Distance Running (LDR) sub-committee. She was also a founding member that year of the Lake Merritt Joggers and Striders Club (LMJS). She said that an important aspect of the LMJS was always to encourage the participation of women runners.

1976 Lake Merced 100K

During the early stages the only scenery was visible by the street lamps until nearly the third lap. She said, “A whole new course seemed to open up before me with daylight and the lifting of the fog.” Her husband John ran with her for a few laps and then took up crew duty in their “pit stop van” which she visited each lap. “It was a welcome Mecca to look forward to after each five miles.”

Things went well. “Somehow the marathon distance went by, then 50 kilometers arrived — halfway! A real feeling of encouragement came at this point. I enjoyed the next three laps. I was surprised how I could run without too much discomfort once I got going again each lap, until the last mile. It was dark again and there were no runners in view.” Her husband and some friends joined in for the finish. “I will never forget that first 100K, a real trip.”

Legendary Don Choi won the 1976 Lake Merced 100K in 7:44:42, unofficially the third fastest time ever run by an American up to that time. Anderson reached 50 miles in 8:30:01 and finished 100K in 11:22:46 which was thought to be an American record, breaking the existing fastest known time of 13:22:05. The unofficial world record was held by Edith Holdener of Switzerland with 8:50:19 set that year in Copenhagen, Denmark.

1977

Special awards started to come to Anderson that year. The University of Nebraska awarded her the president’s award of merit for long service and overall achievement. She kept a close association with the university and would return at times as a distinguished alum speaker. Also a short film was produced about her as the top Northern California masters marathoner and shown at running events. As a running administrator, her work continued tirelessly behind the scenes. She was the first recipient to be awarded the Otto Essig Award for meritorious service to masters’ long distance running. This award continued to the present day.

1978

During 1978, Anderson was in the prime of her masters running career. She ran her fastest marathon times in at least 15 marathons including her lifetime personal best in 1978 at Avenue of the Giants Marathon, in Weott, California, with a time of 3:04:19, finishing in 3rd place. She traveled all over the country competing. Her daughter, Rachel, participated with her at times in races. Anderson ran a 10K halfway with her and continued on, winning with 40:44.

Anderson’s training included weekday 15 km lunch-time running near her lab in a rural setting cross-country course in a nearby park, through redwoods and down in canyons. On weekends she ran hilly city streets, frontage roads. Her husband ran 35-40 miles per week and her daughter ran 10-15 miles each week.

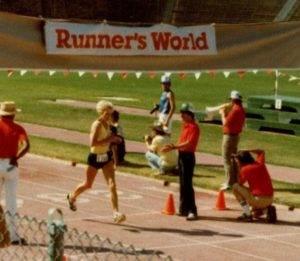

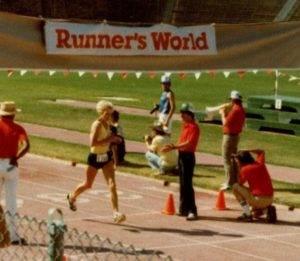

It was then time to try something totally new, where her name would be entered into the ultrarunning history books. In July 1978 Don Choi organized a 24-hour race held at a high school track in Woodside, California. She ran 100 miles in a 16:50:47. That was the second best 100-mile time ever recorded in the world by a woman up to that time. (Natalie Cullimore ran 16:11 on a road course in 1971, at Rocklin California.) This was also the first ultra that was witnessed by a young, soon-to-be Western States 100 legend, Tim Twietmeyer. He commented, “I spent hours watching them circle the track and watching how they paced themselves, what they were eating and how they decided to take breaks.”

1979

In 1979, Anderson continued to run in ultras. In February at the Pacific AAU 50-miler, Marysville to Sacramento, she finished in 7:25:05, and lowered the PA-AAU masters women’s record.

At the Los Angeles 20th Century Fox Women’s Marathon she narrowly averted disaster. A drunken driver side-swiped a woman running next to her. She said, “He zipped in almost like he was running into her and hit her by the side. My first reaction was, ‘It could have been me.’”

During the year Anderson served as a member of the Executive Board of the Pacific Association of the AAU. In 1979, she was elected the Masters Long Distance Runner Chairman for the national AAU and also received the “Masters LDR Woman of the Year” award at the national convention held in Houston.

London To Brighton

Anderson’s husband said she “beat on them” with persistence. Race officials finally relented and she was the very first woman to ever be accepted into London to Brighton. She said, “It was a coup, and it was something I definitely cared about.”

Three other British women also ran. Anderson finished in 3rd place with 7:46:54. She said, “It was one of my all-time goals. One of my dream races.” Years later she said it was her most memorable race.

1980

A feature news article was written about Anderson when she returned to her home of Nebraska to the Lincoln Marathon with her daughter, Rachel, who was a 15-year-old cross-country athlete. Commenting about Anderson it was written, “The average woman hates to admit her age, but not Ruth Anderson. Of course, it could be said with complete accuracy that Ruth Anderson is not your average woman. How many people’s idea of fun is running 54 miles? How many women laugh with glee over their 50th birthday because it will put them in a new age division for road races?”

At the National TAC Convention in Atlanta, she was named the top Masters Administrator of the year for the women’s program. By 1980 she had finished her 60th marathon and she was inducted into the Road Runners Club of America (RRCA) Hall of Fame. That was her proudest achievement.

Trails

In 1981 Anderson discovered the joy of racing on trails. She first had this experience running American River 50, Auburn to Sacramento, and ran it three years in a row. In 1983 at the age of 54, she ran Western States 100 for the first time with a time of 28:11. Up to that point, she became the oldest woman to ever finish. She again finished Western States in 1986 at age 56. She said her happiest memory racing was when her daughter and friends greeted her at finish that year and she said that Western States was her favorite ultra.

Another special race to her was the Sykline 50k which ran along the Skyline National Trail in the East Bay Hills above her home in Oakland, California. She ran in that race for many years starting in 1986.

Anderson was asked about her heroes and she singled out Jacqueline Hansen from Southern California, who was nearly 20 years younger than her, and won nearly every marathon she ran. She was the first woman in the world to run a marathon in under 2:40, in 1975. They ran in many of the same events. Hansen lobbied, finally successfully, the International Olympic Committee to add the women’s marathon event.

In 1986 at the age of 56, Anderson ran Redwood Empire 24 Hours in Santa Rosa on a track. She ran 110 miles. That was her last time reaching 100 miles in a race. Her 100-mile split was a very solid 20:54. She set American age records at 50K, 5:00:17, 50 miles, 8:25:02, 100K, 11:11:03, and 100 miles.

That year a 100K was started in San Francisco around Lake Merced by her friend and training partner, the legendary Dick Collins. It was named in her honor and still exists in the present day.

In 1988 Anderson said her long term goal was to keep running and accepting new and exciting challenges as long as she was physically able to. She hoped to be running and still a “world class performer” in her 80s and 90s. In her 60’s she continued to regularly run ultras, mostly 50Ks. She did slow down, but could run 50K as fast as 6 hours. She once said, “I never let the bad, disappointing, or discouraging event of my life overshadow the good and rewarding events and the encouraging prospect of the future.”

She helped at many races including Western States, American River 50, and the Lake Tahoe Relay. In 1995 at American River, Ken Crouse was working an understaffed aid station. Two ladies walked up and offered to help. They chatted with many runners coming through until the station nearly closed. These two turned out to be legends Ruth Anderson and Helen Klein.

In 1996 Anderson was inducted into the USATF National Masters Hall of Fame. In 1999, at the age of 70, she finished first in her age group at the USATF 50K Trail Championship. She continued to run races, mostly in California, until she was age 72 in 2002 when she ran 40 miles in a 12-hour race. She also ran her last marathon that year, in Lincoln, Nebraska when she finished in 5:37:40. Each year she would come to the Ruth Anderson 100K at Lake Merced to run laps in the opposite direction as the runners so she could offer them words of encouragement.

In about 2003, Anderson and her husband moved to Eugene, Oregon. She had always loved Eugene where she had run the Eugene marathon several times. She was sorely missed by her California running community.

In 2005, at the age of 76 she went to San Sebastian, Spain to compete the World Masters Games and ran in the 8K cross-country race, finishing in 1:17. The games were held every other year and this was her 16th in 30 years, the only woman to compete in them all. At them she had won nine gold medals, eight slivers, and 14 bronzes, running everything from 800 meters to the marathon.

She was interviewed for a news article and asked if she knew how many trophies she had. She responded, “Oh, heavens, no. I’ve given half of the away.” For many of them she peeled the labels off and donated them to high schools. For her career, she had finished 108 marathons and about 50 ultramarathons.

When asked why she still ran, she replied: “It’s the people and the traveling and the experiences. If it weren’t for that, I’d probably be in a deep, dark tunnel somewhere, psychologically. I just enjoy being able to run and to keep running. Gosh, you feel so much better when you do something physical.”

Long-time running friend, Len Goldman wrote of Ruth Anderson, “She was a role model and mentor to many and friend to all. She trail blazed the way for women participating in ultra running events and became an inspiration for generations of women runners who followed in her footsteps.”

Sources:

- Morning Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), Oct 17, 1894

- Omaha Philatelic Society minutes, 1940

- Omaha World-Herald, June 13, 1915,Mar 4, 1928, Oct 24, 1937, Mar 4, 1943, May 11, 1945, Aug 27, 1950, Jun 11, Oct 14, 1951, Dec 18, 1952

- Lincoln Journal Star (Nebraska), Sep 1, 1947, Apr 5, 1953, Jan 27, 1974, Mar 18, 1977, Sep 27, Oct 26,30, 1980

- The Nebraska State Journal, Oct 27, 1918

- Desmos of Delta Sigma Delta, Volume 27

- USATF Ruth Anderson Biography

- The Complete Woman Runner

- Ultraruning Magazine, July 1988

- San Francisco Examiner, Feb 1, Dec 14, 1975

- Ukiah Daily Journal (California) Jan 21, 1979

- Los Angeles Times (California) Nov 4, 1979

- The Register-Guard (Eugene, Oregon), Aug 18, 2005

- NorCal Running Review, many issues 1973-1981

- Association of Road Racing Statisticians

- Jacqueline Hansen, “The Women’s Marathon Movement”

- Joan Ullyot, Women’s Running

- Pioneering Ultrarunner Ruth Anderson

- Ruth Anderson Passes at 86

- A History of Women’s Running

- “The Fight to Establish The Woman’s Race”

- World Masters Championships Results

- Ancestry.com

-

ZDF Sportreportage – 2. Int. Frauen-Marathon Waldniel 22.September 1974