Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:56 — 33.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

|

Nick Marshall Starts Compiling 100-mile Finishes.

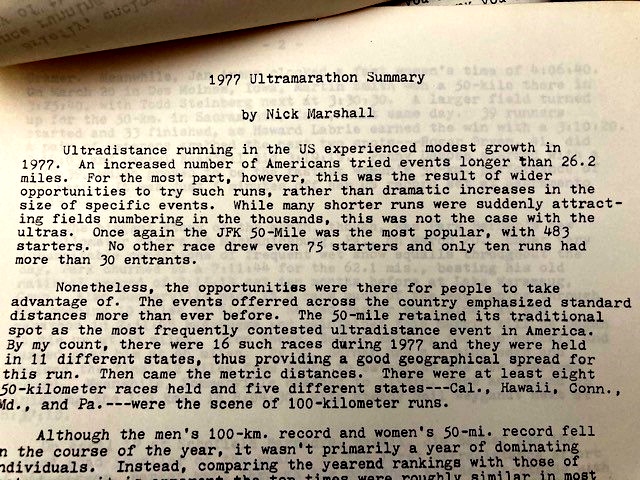

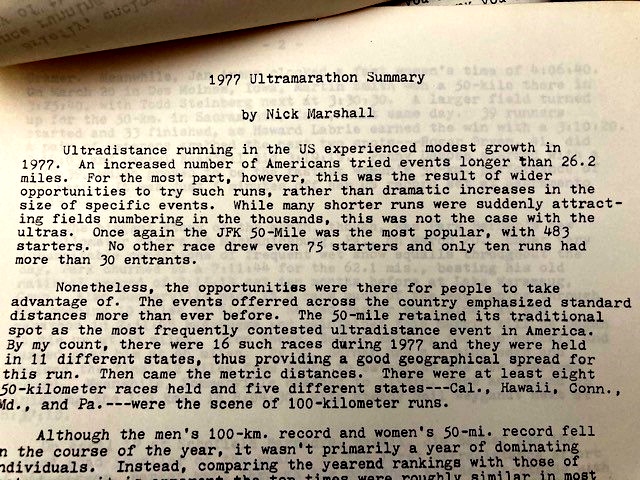

In 1976, future American ultrarunning hall of famer, Nick Marshall (1948-) of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, published the world’s first newsletter dedicated purely to ultrarunning. This annual publication became known as the Ultradistance Summary. Marshall wrote, “There had always been a coverage-void for the fledgling sport, and I sort of filled it by default, simply because no one else was doing anything along these lines.” He explained, “No summary is perfect, but I think this one provides a fairly complete and quick summary touching of the major bases.”

Marshall’s 1977 Ultradistance Summary stated that no formal 100-mile races took place in 1977, but actually a few were held worldwide along with a half-dozen 24-hour races. One significant 100-miler that was overlooked because it was not yet tied into the ultrarunning sport — the first Western States 100 from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California. While the Western States course was actually only 89 miles at the time, the 1977 race has an important place in 100-mile history. (see episode 71).

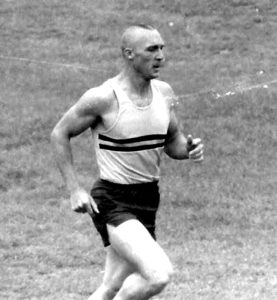

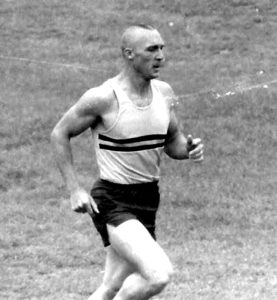

Don Ritchie – the Stubborn Scotsman

Ritchie ran cross-country in school, and during the track season raced the 440 and 880 yard races. His coach advised him to concentrate on the 880. In 1963 at the age of 19, he started to run fifteen miles regularly with Alastair Wood (1933-2003), one of the great ultrarunners of the early 1970’s, who later won London to Brighton race in a record time. Ritchie eventually started to keep up with him on training runs.

Scottish Athletics required that runners be at least 21 years old in order to run in marathons. In 1965 Ritchie was old enough and entered a marathon with Alastair Wood. The furthest Ritchie had trained was 17 miles. He did great and was pleased with his finish time of 2:43. His mentor Wood, won the race in 2:24. When Ritchie finished, he didn’t say “never again,” he was excited to run more marathons. His personal best for a marathon would be 2:19 at the London Marathon.

Ritchie’s best running year of his life was in 1977, at the age of 32 when he was a schoolmaster. In April, he broke the world 50 km track record at Ewell, England, with a time of 2:51:38 taking more than four minutes off the previous world record. He beat the 100-mile world record holder, Cavin Woodward by about 23 minutes. He followed that up by winning London to Brighton that year, despite being ill. Just three weeks later, he would run perhaps the greatest race of his life at a 24-hour race at the Crystal Palace at London, England.

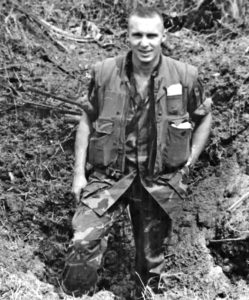

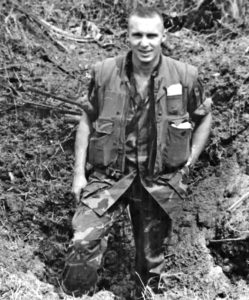

Frank Bozanich

While recovering in a roman bath, he was approached four or five guys. “They said, ‘We would like to invite you to run at the Crystal Palace 24-hour race in London in three weeks. We are limiting it to twelve runners. We would like you to be there.’ I said, “I’ll be there.” A half hour before I said I wouldn’t run another ultra.” He returned home to San Diego and successfully received orders from the Marines to return to England and run in the historic 1977 race at the Crystal Palace.

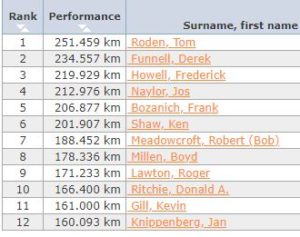

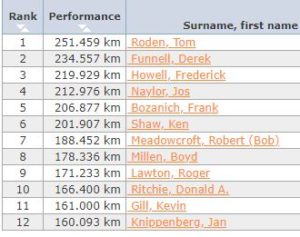

24 Hour Crystal Palace Track Race

The Start

On October 15, 1977, Ritchie, Bozanich and ten others started out on the historic 24-hour race. Bozanich said, “When the gun went off, Don Ritchie was gone. I didn’t know any better so I hung with him. He was one determined guy and focused. He just put his head down and went.”

Ritchie indeed went out blazing fast. His first ten-mile split times were, 1:02, 1:03, and 1:02, reaching 50K in 3:15. At about mile 40, his feet and legs started to become sore. He speculated that it might have been due to the warm afternoon’s effect on the synthetic track surface. He took salt tablets and fueled on a special carbohydrate drink with vitamin C and potassium.

Bozanich also started to have issues. “I had gotten a blister on my toe and was trying to fix that. A young guy comes over who was the brother of Jan Knippenberg, a runner from Holland in the race. He was a doctor and asked, looking at the two marines without any crewing experience, ‘Is this who you have for your team?’ I said ‘Yes.’ Knippenberg the asked, “Would you like to come over and set up by us and we will help you out?” Bozanich was delighted to receive the kind help. “I went over there and they started taking care of me and helped me.”

Ritchie Breaks the 100-mile World Record

Ritchie said, “I ran for 100.5 miles before stopping to have a massage and to look at my feet, which were hurting badly. I had two blisters on my left foot and my right had three blisters plus a cut. I changed my shoes and tried walking, but I could not make myself run again. The outside of my right foot was also painful from favoring the inside where the blisters were.” He decided to drop out of the 24-hour race but he broke the 12-hour world record with 100 miles, 727 yards. He couldn’t run again for four days because of his torn up feet.

The 24-hour Race Continues

Other runners continued. Bozanich said, “The hard part was just trying to keep going. I was used to running 50 miles where I could just drop the hammer and hang on but I came to find out that I had to do double that and more through the night. I never stopped to take a nap. I slowed down a lot.”

Bozanich reached 100 miles in 15:21:56 and Knippenberg retired after reaching 100 miles in 17:21:42. Only seven of the starting twelve reached 100 miles. Knippenberg’s crew kindly committed to crew Bozanich for the full 24 hours. From them, he learned the virtue of eating baby food for the first time during an ultra.

Jim Shapiro’s 1977 Article on the Ultramarathon

He was a graduate of Harvard and served in the Peace Corps. “Quite by chance, in 1974, I saw the finish of the Boston Marathon. Then it became very simple: I had to run one too.” He started to train and soon was running marathons. He became a member of the Boston Athletic Association and visited physiotherapist, Jock Semple (1903-1088) at the Boston Garden for some treatment. Semple gained fame when he tried to tear off the bib number of Kathrine Switzer when she ran the Boston marathon in 1967.

Shapiro and Semple discussed ultramarathons and Max White’s impressive 1973 fourth place finish at the famed London To Brighton (52 miles) race. Semple remarked, “Why, for the love of Pete, does he want to run such things? That ultra stuff is for old men, fellas at the end of their running careers. There’s no future in it, none at all. Why it’s a disgrace how the Boston papers don’t even print a paragraph on it. Nobody cares about such stuff. He should run marathons, that’s where the glory is. Why run these things if you don’t get proper credit.”

Shapiro understood the personal attraction for running ultradistances. “I had some success in competition, which was rewarding, but my taste really veered more toward private solo run, the fifty-mile crunchers.”

He started to run further and further. In the age without Garmin watches, he would meticulously measure his runs in Manhattan with an expensive swiss-wheeled map reader along topographical maps pinned to the wall of his apartment so he could know how far he had run within a hundredth of a mile. He said, “The ultra-distances are so long that simply to cover them can be for some an achievement that matters much more than the speed with which it is done.”

In 1975 Shapiro went to Mexico to witness firsthand the culture of the Tarahumara and their legendary distance running abilities. He hoped to learn something about running from them. He came away very impressed and wrote, “In a way, I hope that the Tarahumara are left to practice their ultrarunning games among themselves, on their own terms.”

Shapario’s 1977 Article

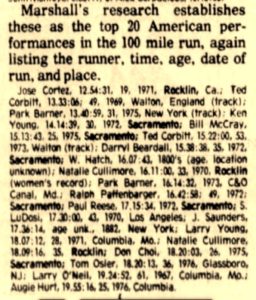

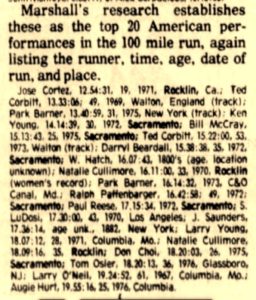

The article went on to feature Ted Corbitt, Park Barner, Tom Osler, and Max White. Shapiro later taught that an ultramarathon at a minimum was a race of 50 miles or longer. He felt that “races that cover only 40 or 60 kilometers really have more of a character of a marathon than an ultra.”

While the 1977 article introduced the ultra to the country, it also painted a picture that it was an outlier, odd sport. “Reactions from other runners range from awe to incomprehension. A familiar comment is: ‘That’s crazy stuff.’” He continued to publish articles about ultrarunners. In Harvard Magazine, he used the term ultrarunners and described them as “the authentic crazies of the sport, the swept together cuttings who represent every kind of motivations and background. They are the mammoth distance specialist, inspired lunatics who yearn to accomplish mind-breaking feats”.

Shapiro went on to write many books including the classic 1980 book, Ultramarathon which is now a rare book. That year he also ran across America in 81 days. He went on to teach in high school. One of his students said, “He’s hands down the most amazing teacher I’ve ever had. He used to tell us about 100 mile runs, and it absolutely blew my mind. He’s one of the most generous, kindhearted people I’ve ever met.”

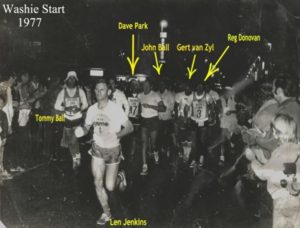

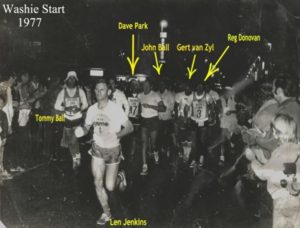

Washie 100 in South Africa

Other 1977 100-mile and 24 hours races

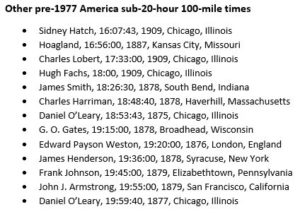

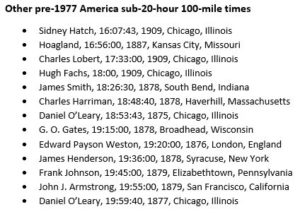

On November 11, 1977 a 100-mile track race was held at Auckland, New Zealand. John Hughes (1933-) won in 12:59:24. Numerous 24-hour races were held in European countries. Four were held in Italy and two in Czechoslovakia, and the race at the Crystal Palace. Len Keating (1940-2016), originally from Scotland, ran 100 miles on a track in Zimbabwe, Africa in 16:21:31.

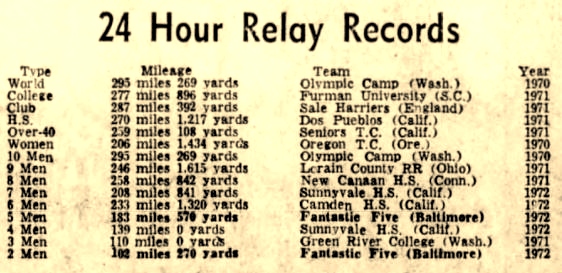

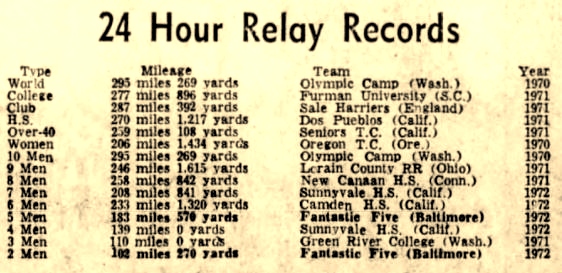

24-hour Relays

In the 1970s, a 24-hour relay craze took place at high schools, colleges and running clubs. Records were claimed, but hard to compare because the number of team members in the relays varied so much and record keeping was always suspect. These type of running relays took place as early as 1907. In 1930 at Montreal, a professional race of six two-man relay teams competed for 24 hours against each other and six teams of horses. The winning team reached 211 miles, 11 miles ahead of the first horse team.

In 1959, at Melbourne Australia’s Olympic Park, a large 24-hour relay race involving 20 clubs was held with teams of unlimited sizes, although each competitor had to run at least four miles. The road course was a one mile loop around the Park. The winning team reached 275 miles.

In 1968, 37 members of the Simi Valley High School Pacer Club in California ran 257 miles in 24 hours in stiff “Santa Ana Winds.” The wind became so bad, that the boys started to run relay legs of only one lap. They believed that they had set a record.

In 2021, the 24-hour world relay best for 10 runners was thought to be 302.2 miles set in 1994 by Puma Tyneside Running Club in Great Britain.

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources:

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia), Apr 15, 20, 1959

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), Dec 29, 1964

- The Van Nuys News (California), Feb 13, 1968

- Corvallis Gazette-Times (Oregon), Mar 7, 13, 20, 1970

- Longview Daily News (Washington), May 16 1970

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Jul 21, 1970

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Aug 14, 1970

- The Greenville News (South Carolina), May 23, 1970

- Times Colonist (Victoria, Canada), Aug 30, 1971

- The Herald-News (Passaic, New Jersey), Aug 23, 1971

- The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Jun 7, 1972

- Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Texas), Jun 12, 1972

- The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), Jul 1, 1972

- The Los Angeles Times (California), Aug 8, 1937, Sep 24, 1978

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia), Aug 1, 1937

- San Diego Tribune (California), Nov 4, 1969

- Sacramento Bee (California), Jan 20, 1977

- Colorado Springs Gazette (Colorado), Nov 30, 1977

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Sep 18, 1977

- The Honolulu Advertiser (Hawaii), May 24, 1979

- James E. Shapiro, Ultramarathon

- Don Ritchie, The Stubborn Scotsman

- 2021 Interview with Frank Bozanich

- Frank Bozanich, “From Vietnam to National Champion”