Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:01 — 34.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

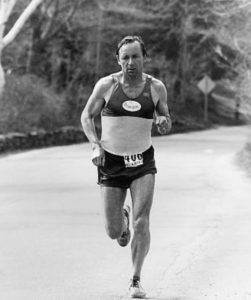

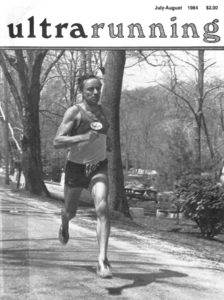

Heinrich appeared suddenly on the ultrarunning scene, setting a record in his very first ultra, and he quickly rose to the top of the sport. He was named “Ultrarunner of the Year” three of the first four years of Ultrarunning Magazine. He had a quiet nature and never sought for the running spotlight, but eventually was one of the few to be inducted in the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.

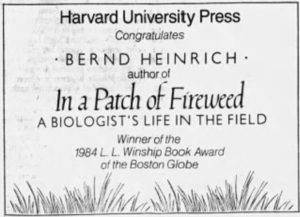

As a boy, Heinrich grew up living deep in a forest in war-torn Germany. In his life priorities, running was secondary to his true love, observing, researching, teaching and writing about nature. During his intense running years, he was able to find a balance to become a world-renowned expert in his professional naturalist career. Ultrarunning historian, Nick Marshall wrote about Heinrich in 1984, “Often runners don’t know much about the backgrounds of individuals whose athletic accomplishments may be very familiar to them, so it is quite nice to see one of our sport’s star gain recognition as a successful pioneer in a totally unrelated field.”

Childhood in Germany

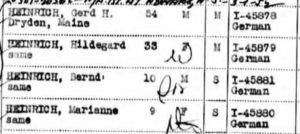

Bernd Heinrich was born in Poland in 1940. Near the end of World War II, he and his family fled their large farm near Gdansk to escape advancing Russian troops in 1944 and crossed what would be the future boarder for East Germany. Henrich recalled, “The times were not easy. The biggest problem was filling our bellies. Papa decided that the best chance of finding food would be in the forest. We came across a large reserve called “the Hahnheide,” and within it a small empty hut used before the war by a nature club from Hamburg. The forester in charge gave us permission to move in. We lived deep in the forest for five years. We had no work and hardly ever any money.” They survived by foraging for nuts, berries, mushrooms, and hunting small rodents and ducks. This experience began his love for nature and was, “a rare mix of survival and enchantment.”

Heinrich recalled, “We were totally immersed in nature. Like most animals, our major concern was finding food. I didn’t like picking berries because I had to move so slowly, from bush to bush. I much preferred picking mushrooms when I could run at will through the damp forest, feeling the soft green moss under my bare feet.” Young Heinrich collected beetles and birds’ eggs for his family’s food supply. He became obsessed with the creatures around him. “I had no playmates and never owned a toy. Yet I didn’t feel deprived. Who needs toys after having seen caterpillars from up close and knowing they can turn into moths?”

Heinrich became fascinated with bugs and insects. When he was nine, he drew a birthday card for his father and on the back, he wrote that he had collected 447 beetles of 135 species. “I loved spending all day in the woods, and I dreaded the idea of growing up and having to work all day.”

He said that he discovered “the joy of running after tiger beetles through warm sand on bare, tough-soled feet.” He said, “When I was a child my family called me Wiesel (Weasel) because I was always running through the forest. A lot of people might think of it as a deprived childhood. I feel just the opposite. I see people in the suburbs as very deprived. They don’t get to touch nature.”

In April 1951, the Heinrich family immigrated to the United States and settled in Wilton, Maine, where he continued living by the forest in an old run-down farmhouse. His parents had little means to earn a living and worked to collect birds to be sold as museum specimens. Young Heinrich ran through the forest collecting birds for his father’s collection.

Soon his parents went off to Mexico and Africa to collect specimens. He and his sister were sent to the Good Will boarding school for disadvantaged and homeless children. His childhood was difficult because his school guardians “tortured him mercilessly” for six years.

The school included a forest of 3,000 acres and he would flee into the woods where everything was familiar and peaceful. He said, “I eventually cleared about a half-mile stretch on one of our forest trails that I ran all by myself, feeling the freedom of wind on my face.” Once he ran away from the school with two buddies. They travelled about fifty miles during the day and night until they became so hungry and tired enough to willingly be caught. He was small and awkward and was often mocked because of his interest with bugs and birds. He said, “My favorite form of play in the summer was looking for bird nests or caterpillars.

Cross-country in school

Heinrich ran track and cross-country in high school and by his senior year was the school’s best cross-country runner. He said, “After that I was no longer derisively called ‘Nature Boy.’ I was instead ‘an animal.’ That sounded much better, in fact, it felt great. High school cross-country had provided me the transition from running to racing. I had tasted the lure of the chase, and I was changed.” Asked why he took up running as opposed to the other sports, he replied, “For some reason it just seemed more natural. It seemed unadorned and simple, direct and it didn’t seem like a game. It was something I could practice at any time or any place. It appealed to me because I could do it all the time wherever I was. No matter where I was, I could always run.”

One of the main reasons he went to college was to run cross-country. He said, “I owe a lot to running. It’s probably the only reason I went to college.” When he applied for schools, he was rejected four times, but finally found a college home at the University of Maine at Orono where he majored initially in forestry and then switched to zoology.

To get ready for his first cross-country season, he had a summer job trying to trap gypsy months. He set nearly 500 traps and when he went to check them, he would stop his car about 100 yards away so he could get in short runs over and over again.

Once at college, knowing that he was small, he tried weightlifting but ended up with a ruptured lumbar disc and the doctor told him to not do any more running. He did join the cross-country team but didn’t do any serious running that first year. But for his sophomore year, he had healed up and was ready to run again. He said, “That year I flew. I was with the leaders of the pack, and my spirits soared.” His 1961 team was the best east of the Mississippi in their division he won the two-mile track championship with a time of 9:24. His coach announced that Heinrich would be the team captain for the next year.

Heinrich was determined to lead his cross-country team to another championship and vowed to not let them down. But then his father asked him to go spend a year with him in Africa for his father’s last great expedition. Just as he was likely to get a national spotlight put on him for his extraordinary running talent, he decided to put that aside for his greater passion. He said, “There was no question that this would be a once-in-a-life-time experience, and it was my only opportunity to be with my parents and to see the life I had heard so much about. I had to go to Africa. Years later, I would realize how profoundly this trip influenced my thoughts about running.”

So off he went to faraway Africa with his parents on this Zoological expedition. His father was a self-taught taxonomist, specializing in wasps. Heinrich’s job for thirteen months was to hunt birds and to skin and prepare them for a museum research collection. His only diversion was to collect insects. What about running? “I had no reason to run, but when we were near a dirt road, I usually did run when our busy schedule allowed. I once ran barefoot as I had seen Africans do while winning at the Olympics. But the soles of my feet became like raw hamburger. I could not walk for about two weeks.”

On returning to college in 1963, Heinrich ran well, but not outstanding because he became injured when he tore some cartilage in his knee while pushing his small car down a hill to start it. But in his final race at the university, he was determined to get his name up on the field house wall as a school record holder for the two-mile run. He ran his heart out on pace for the record, but an official lost count of his laps and didn’t properly fire the warning gun to indicate his last lap to sprint. When he did kick hard, it was for a lap beyond two miles. He had missed the record by two-tenths of a second. It would be a lasting disappointment.

Heinrich graduated with a biology degree and then received a master’s degree from the University of Maine. He next traveled west, enrolled in UCLA, and eventually received his Ph.D. in zoology. He became a world expert on bumblebees. During his studies and research during the 1960s he raced now and then, but was more focused on his work. He didn’t identify himself as a runner, even though sometimes he ran 140 miles during a week. He said, “My work with certain insects is where most of the percentage of my energy went.” He ran regularly on the UCLA track, mostly quarter and half mile intervals and formed a social running team. “One of the guys on the team talked about someday racing 26.2 miles, a marathon. I thought he was nuts.” In 1968 he married Kathryn in Los Angeles, California.

Professor at Berkeley

In 1970 Heinrich became an assistant professor at University of California-Berkeley. He ran a lot on the track at Berkeley and said, “When I was there, there was a horse trainer who would go to the track. He would analyze my style and make recommendations about my arm swing and cadence. He made me much more conscious of my stride. One should not underestimate the coordination that is involved in running.”

While corresponding with the world’s premier biologist of social insects, Edward O. Wilson at Harvard University, Wilson mentioned that he was a runner too. He reviewed Heinrich’s running history and declared out the blue, “You could run a sub 2:30 marathon.” Heinrich became determined to prove him right.

Marathon Running

As Heinrich trained for his first marathon, his knee pain reappeared and an orthopedic surgeon advised him to stop running. Heinrich hoped that things would get better and they did. In 1975 he ran the Boston Marathon and he finished with an impressive 2:23 in 46th place, beating Wilson’s prediction. Wilson later mentioned, “When he was studying the flight patterns and orientation of bumblebees, he’s the only biologist I think I ever knew who actually got his data and checked it by running with the bumblebees as they flew back and forth between their home and wherever they were going.”

Heinrich had another personal goal that he worked very hard to achieve. He wanted to run a sub-two-minute half mile (880 yards) and said, “I finally did, all by myself one Saturday morning on the Berkeley track.” It was only witnessed by a friend, Max Mische, who came because he knew I was going to try.”

Beetles and Bumblebees

Also during 1979, the Scientific American sent Heinrich and another professor to Africa to research the African Dung Beetle which fed on elephant dung. They published an amusing and interesting article about the beetle that would doze all day and then, after sundown, the flying beetles arrived in great humming clouds to feed on the poop. Heinrich traveled to other places. He also chased butterflies in New Guinea and researched moths in Costa Rica.

Heinrich published a book titled, Bumblebee Economics. He shared stories of the industrious creatures and found many implications for mankind. The book received excellent reviews. He said, “I can’t directly apply bumblebees to running, except they have the same problems as us, like overheating and storing enzymes in muscles, but my science is helping a lot by my running.” He was a world authority in insect thermoregulation. But he said, “I got bored with insects, I could predict too much. After you’ve been doing the same thing for years, it’s not fun anymore unless you make big discoveries.” Some of his Berkeley colleagues that he was crazy to move on from insects.

Heinrich continued to run marathons. In February 1980 Heinrich ran his lifetime personal marathon record of 2:22:36 at the West Valley Marathon in San Mateo, California, missing qualifying for the Olympic Trails by only 40 seconds.

1980 Boston Marathon

Next he ran in the famous 1980 Boston Marathon featuring Rosie Ruiz who was caught cheating the win. Heinrich was caught up in a little controversy of his own. He finished in 2:25:25 which was good enough for first place masters (over 40 years old). But at first, the race officials believed he was 39 years old, not knowing that he had turned 40 two days earlier.

First ultramarathon

Even with his master’s win, Heinrich was disappointed in his performance. He had been content with running marathons until he noticed that he was passing a lot of runners toward the end of his races and he knew that he could run much further. He decided to pursue longer distances. Around that time, he left Berkeley, moved to Burlington, Vermont, and took a position as a professor of zoology at the University of Vermont. He promptly joined the Green Mountain Athletic Association and became their star runner, the 4th fastest marathoner in the state.

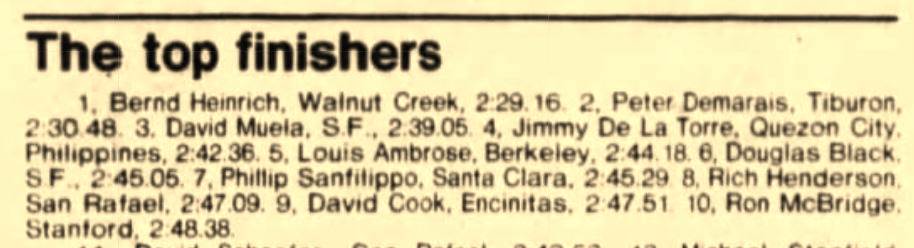

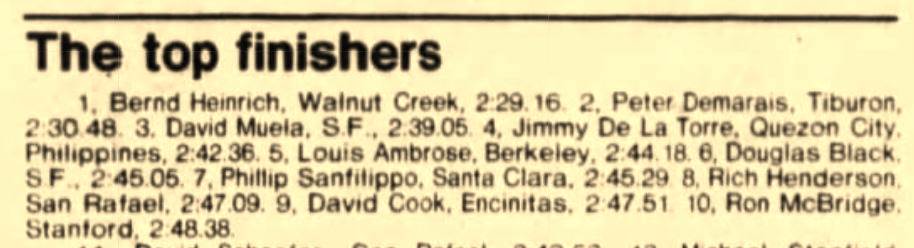

He ran his first ultra in November 1980, a 50K race, The Athletic Congress (TAC) national championship held in Brattleboro, Vermont. He finished in third, but set the American Masters record of 3:03:56 in his very first 50K! In that race, he beat the current 100K American record holder, Frank Bozanich, and that gave him the confidence to try racing 100K next.

On May 19, 1981 Heinrich suffered a serious knee injury while chopping a tree, tearing his meniscus. He had surgery, and in those days they opened up the knee and removed the medial meniscus. His surgeon said, “If you don’t stop running, I’m going to have to take off your knee cap” and said that he only had a certain number of miles left on his knee. “I figured I’d better get that mileage in now rather than frittering it away slowly to no effect.” He first convalesced in his cabin in Maine watching ants for days, but a couple months later he was running again.

The historic 1981 100K

At the age of 41, Heinrich did not just want to race his first 100K, he wanted to win the National Championship held in October 1981. He started his training in mid-June in Maine with a ten-mile week. He added ten miles every week until reaching 140 miles and then tapered in September with 110-mile weeks. He never took days off. He explained further, “I did not know any other ultrarunners, nor did I know of any training manuals on ultrarunning. I was up there in the woods by myself, so I trained the way I thought I should. I felt I had to do long, hard runs. I tried to tax myself, then allow for rest and recovery.” On fueling he said, “I found eating solid stuff was great at slow speeds but it made my mouth feel like cotton on hard runs and I couldn’t get it down. Liquid carbo was easiest to get down.”

Returning to teach for the school year in Vermont, Heinrich continued to run – all the time. “I never walked. Even if I needed to go only 50 yards to the library or to my car, I jogged. My body must not be allowed to think it could ever walk again.” His long runs were usually to and from work.

Instead of going to the pre-race meeting the night before, he went down to the Lake Michigan shore to check out the start line and jog part of the course. There he met Ray Krolewicz of South Carolina for the first time. Heinrich wrote, “I didn’t know it then, but Krolewicz was a veteran who had already raced in more than sixty ultramarathons. I had raced in only one.” Heinrich’s impression of the course was that it would be long and boring, but he considered it a challenge.

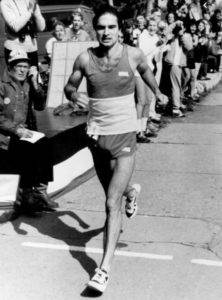

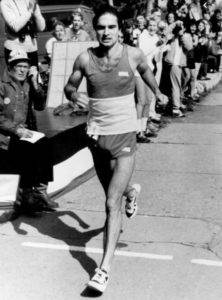

The next morning, at 7 a.m. in the dark, Heinrich lined up with with 261 runners from 30 states. As he ran the first few miles, Krolewicz ran beside him, “talking a blue streak.” Heinrich couldn’t listen. He was lost in his concentration. Heinrich pushed ahead of Ray. The favorites including Klecker, disappeared down the road. Heinrich concentrated on initially running 6:15-mile pace. Timers along the course would “holler” out the race time. Heinrich’s strategy was to “never speed up, never slow down, and to not stop until the finish.” He hit ten miles at 1:03, and was 8 minutes behind the leaders. His next three ten-mile splits were all 1:01. He hit the marathon mark at 2:42. The leader, Barney Klecker, was ahead of world record pace.

After each lap, Heinrich was met by his “handler” Jack, who had him drink the cranberry juice. (He ended up drinking 1.5 gallons). After four hours, the day was hot and the wind picked up. Jack told him that Klecker was fading ahead. Heinrich was in second place. He hit 50 miles in 5:10, setting an American Masters record which stood for many years. Klecker dropped out after 50 miles, so Heinrich was in the lead continuing on to 100K. He pushed on ahead, always fearful that another runner would catch him, but he crossed the finish line in first place with a time of 6:38:21 (averaging 6:26 miles). He set an American Record and World masters record. He didn’t even know what the existing record was, nor did he at first know that he had broken it. His time was only second on the all-time world ranking list only to Canadian Richard Chouinard’s 6:36, set two years earlier.

He later wrote, “One would think I’d have raised my hands in triumph and pranced about like a mad banshee. However, I was much too exhausted to raise even a finger; instead, feeling a deep quiet, warm glow, I collapsed onto the soft, cool grass in the shade of a tree. I felt unimaginable contentment as my heart pounded a long time from the hard finishing sprint.”

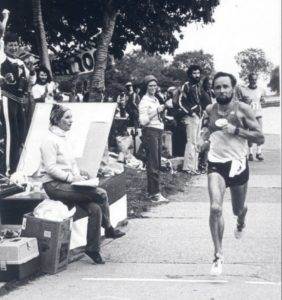

![]()

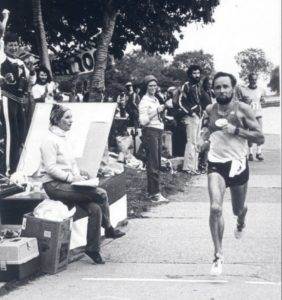

![]()

Heinrich’s hometown Burlington, Vermont newspaper wrote, “Ultramarathoning, in a sense, is the new frontier in distance running. Slowly gaining acceptance, the land beyond the marathon, is just now filling up with a pool of top runners. Bernd Heinrich is one of them. Right now, he stands as king.” Heinrich said, “It feels unreal to me. I never thought I was a fast runner. Always thought I was a plodder. Basically, I race against myself. I don’t care about beating people that much. I do, however, get a thrill about breaking a record.”

Heinrich thought that was the end of that. “I promised myself that it would be the only ultra I would do in my life. I did eventually break the promise that I had made to myself and to my wife to not run others.”

Ultrarunner of the year

The impact of that performance really got his ultrarunning career started and recognized. Ultrarunning Magazine recognized his race as the performance of the year and crowned him the Ultrarunner of the Year.

Heinrich suffered from a foot injury in 1982, but in November, he went to run Rowdy 50 in Brunswick, Maine to see how we would do, planning to take it easy. He explained, “But at the marathon mark I was 2:42 so I thought, hell, this is two minutes faster than I was a Chicago.” He tried to speed up, but ended by slowing. “I felt like death warmed over the last ten miles.” His choice of fueling with cranberry juice required him to constantly stop for bathroom breaks. “I was glad the race was all through forests, rather than crowded streets.” Heinrich still came away with the win, running 50 miles in 5:22 which was one of the top 50 times for the year.

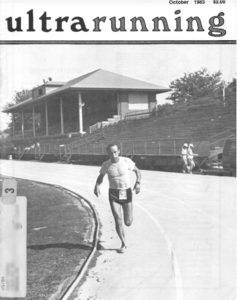

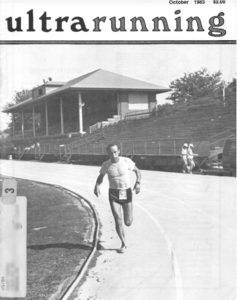

24-hour America Record

By 1983 Heinrich calculated that he had run nearly 70,000 lifetime miles. That year he entered the Rowdy 24-hour race on a track at Brunswick, Maine. His goal was to set the 100-mile American record. The race didn’t go as expected. He explained, “It was a very warm day and I soon knew I had no chance at the record. I hadn’t really planned to go 24 hours. I had planned to drop out after 100 miles.”

Heinrich reached 100 miles in 14:29:04. With the help of his brother-in-law, Charles Sewall, crewing, he set his sights on the 24-hour American record. His 50-mile splits were 6:43, 7:35, and 8:40. “At the end I was only thinking about one thing, the record. I was so close but I didn’t think I was going to make it.” After about 70 miles he used a pattern of running five miles and then walking a lap. He took in juice and baby food which could be swallowed easily.

Finally it came down to the last five miles and Heinrich needed to run sub-seven-minute miles to get the record. He pushed very had and did it, reaching 156 miles, setting an official American Record that would stand for seven years. (In 1979 Park Barner, of Pennsylvania, had set the unofficial record of 162 miles, but it wasn’t officially recognized because timers didn’t follow the strict time recording procedures required by The Athletic Congress (TAC )).

Recovery was rough for Heinrich. He was so dehydrated that he was taken to the hospital for treatment. Also his left calf muscle was in bad shape. He was very grateful that the direction on the track had changed every two hours which helped his calf. But despite how he physically felt after the race, Heinrich was in ecstasy thinking, “I did it! I did it!” He had been acutely aware of the probability of failure, but said, “you can’t see or feel sunshine without shadows. You can’t feel happiness without having felt disappointment.”

However, a few months later in 1984, TAC (The Athletic Congress), the predecessor of US Track and Field, tried to expand their power further over ultrarunning and in the process voted unfairly to disallow the record set by Heinrich, charging that he used pacers during the last hour of the race when race staff came out on the track to run. This action came as a complete surprise to Heinrich as he had never been contacted before the vote.

The race had been on a track with many other runners and race monitors around him. He said he was just running his own race as he always did. But someone told TAC that other runners around him were pacers. Heinrich said, “I did not feel it was my business to tell anyone to get off the track. At that point I was thinking only of one thing, running as fast as I could.” None of the runners or race staff knew about a pacing rule. Heinrich was a victim, being penalized by the enforcement of an obscure rule at that time. Heinrich always trained by himself and felt no benefit from those unofficial runners on the track. TAC officials clearly lacked understanding and fairness. They eventually reversed their ruling at the end of the year, recognizing the record.

100 mile American record

Heinrich concentrated on his next big race, the Sri Chinmoy 24-hour at Ottawa, Canada, at Terry Fox Memorial Stadium. He trained running about 170 miles a week before the race and used short races as training tempo runs, including at Lake Waramaug in Connecticut, where he won both the 50-mile (5:29:01) and 100K (7:15:01) races, beating a talented elite field in both distances.

In May 1984 he had the race of his life at Ottawa, Canada, and reached 100 miles in 12:27:01, breaking the existing unofficial American Record set in 1971 by Jose Cortez of 12:54. Heinrich also set the 150 km American record. His 100-mile time was the 6th fastest 100 mile time ever in the world at that point. He stopped his 24-hour race after reaching the 100-mile mark. His 100-mile record stood for more than two decades.

Heinrich, assisted by his crewman, Darren Billings said, “It went just about as we planned. I wanted to run a seven-minute mile pace. I figured if I could do that, I could slow down later when I got tired and still break the record.” He hit the marathon mark at 3:03 and 50 miles in 6:00, after which he slipped to an eight-minute-mile pace. Heinrich added, “Billings told me if I wanted to break the record, I would have to keep that pace to make 12:40. I thought that was a little close.” He spent the last 25 miles “playing mind games” as he counted off each quarter-mile. He then stepped up the pace to seven-minute-miles again and claimed the record. “I felt basically very well when I finished.” Asked if he would go even greater distances, he replied, “Usually I have one goal at a time, but now, I’m in limbo. I have too much else to do.”

Bumblebees in Maine

That year a film was produced featuring Heinrich entitled, “The Plight of the Bumblebee.” It was shown on public television all over the nation. He taught that the bee must find food and return to the nest with a greater amount of calories than she burns working with the flowers so as not to be in a calorie deficit.

100K track American Record

On Aug 31, 1985, Heinrich set the American Track Record for 100K by 14 minutes with a time of 7:00:12 at Rowdy Ultimate 24-Hour in Brunswick, Maine. A fellow runner at that race said, “Heinrich made it look easy. He doesn’t say much, but he has my utmost respect.” The 100K record stood for 30 years until Zach Bitter beat it by two minutes in 2015. At that time in 1985, Heinrich also held the American records for 100K on road, 100 miles and 24 hours. Clearly, he was the American best. Ultrarunning historian Andy Milroy commented about Heinrich, “His record as a setter of national ultra bests was remarkable; the pity is that he never had (or never took) the opportunity to test himself against international competition.”

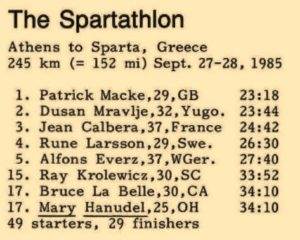

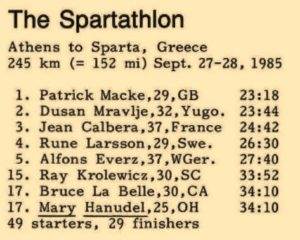

Spartathlon

Away they went, first running in Athens. For the first ten miles, the pace seemed “agonizingly slow,” but Heinrich purposely was holding back. As the day became warm, he continually traded the lead with a Hungarian runner. After five hours, they left the outskirts of Athens behind them and entered winding roads along the coastline that reminded Heinrich of the coastal road in California north of San Francisco. The Hungarian’s coach’s car came by and the coach leaned out from the window and shouted instructions as there were a few runners ahead of them. They caught up with a runner from Denmark who had run 62 marathons with a best of 2:16. The three ran together for several miles.

Henrich later reflected on his successes and failures. “I have never been consoled by the thought that the failures might sow seeds of personal growth. I know that each failure was due to some mistake that only I, and nobody else, had made. That is the beauty of running. There is no such thing as luck and when things go wrong you have no one to blame but yourself. Failures must be faced, and almost welcomed. Failures are experiments that can be invaluable steps toward success.”

Ravens and running

At his home in Vermont he also spent time as a environmental advocate, working publicly to fight a golf course being put in nearby. He said that the golf course would eliminate some beaver ponds and he feared that the herbicides and pesticides used at the golf course could affect the water.

In 1987 Heinrich ran the Philadelphia to Atlantic City 100 km race, a race patterned after the classic London to Brighton in England. It was won by Charlie Trayer for the 4th straight year. Heinrich came in 5th with 7:56.

In October 1992, Heinrich ran again. He entered the Del Passatore 100K in Washington, D.C. because he had time while he was writing a book called, A Year in the Maine Woods. For training, he ran by himself on the lonely wooded roads feeling alive. He was curious how well he could run now that he was in his 50s. He hoped for the national championship but he came in 7th overall but was the first masters.

Retirement from ultrarunning

During the rest of the 1990s, Heinrich focused on his Zoology career. He said, “I could still run, and did all the time. But in no way could I take basically two or more days and dollars out of my life and tight budget to do a race when I could run anytime out my door and into the woods and back, and all without any hassle. Why race?”

Heinrich’s love to run never left him. In 1998 at the age of 58, he was curious how fast he could run a mile. He measured one off and ran it in 5:20 but pulled a calf muscle and was left with a sore knee. Looking back on his running career, he was asked if he would have done anything different. His reply was, “I’d have started ultras earlier in age, having more faith in myself in the ability to finish one.”

Running in his 60s

Heinrich did eventually race again. In 2001, he first ran Lake Waramug 50 in 7:28 which was a disappointment to him. His bad knee really hampered his effort. But he kept trying. That year at the age of 61 he ran in the Maine Track Club (MTC) 50-Miler at Brunswick, Maine and finished in 6:39:55 which set an American Record for age 61.

In 2002 at age 62, he went back to defend his title. His recent training had been good with about 100 miles per week leading up to race day. The race was low-key with twenty-two runners. He decided to run the 50K division instead. He finished first in 4:04, more than an hour before the next runner.

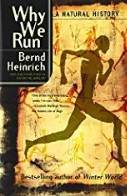

In 2001, Heinrich wrote a fascinating book, Racing the Antelope: What Animals Can Teach Us About Running and Life. He later released it in paperback form, changing the title to: Why We Run. He said, “Running has given me a lot of my perspective. A lot of my research is related to exercise and endurance, temperature regulation, metabolic factors, what kind of fuel to burn.” He claimed that humans can outrun the fastest animals on earth because having a long-term goal in mind gives them the ultimate endurance. “We evolved as endurance predators; we had to out-sprint the antelope, and that takes the vision to pursue.”

He had remarried to Rachel in 1996 and enjoyed watching his four-year-old son Eliot carrying around a salamander and seeing his one-year-old daughter, Lena, sticking worms in her mouth. “She’ll learn soon enough what tastes good and what doesn’t.”

Heinrich talked about achieving running success. “The ultimate weapon of the long distance runner is the mind. When it gets painful, you have to think about the rewards up ahead. You have to keep that dream in your mind.”

About training, he said, “I never saw an antelope stretch. I would never think of riding a bike, or weight-lifting or stretching. It seems ridiculous to me, totally wacko. I’ve never seen a single piece of data to prove that any of things work. I always thought the safe thing was to let the body decide the right thing to do. Time was also a factor in all of this. I just did not have the time to do everything, so the 15 minutes it would take to stretch I felt was better spent running.”

In 2004 Heinrich was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was then a Professor emeritus of biology at the University of Vermont. In 2007 Heinrich was also inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.

In 2008 he opened the door to his aviary and set free all his ravens. He had studied ravens for 25 years. “It felt good. I liked keeping them. I felt I had to look up close to see their interactions. I just decided they had told me enough.” At one time he had 42 ravens.

When Heinrich reached the age of 70 in 2010, he had his eyes on the age 70+ record at Boston, but he withdrew when he realized he could only barely run 8-minute miles. He was sidelined for a few years with knee injuries and arthritis, but eventually his knee improved and he was back running.

By 2019 at the age of 79, Bernd Heinrich still lived in Vermont and Maine, and was working on his 23rd book to be released in 2020 entitled, White Feathers: The Nesting Lives of Tree Swallows. This book will share his observations and studies of swallows that nested close to his Maine cabin. He was still active lecturing and sharing memories of his amazing ultrarunning days.

Heinrich reminded all of us, “In our modern lifestyle, we are not runners anymore, so we are basically disconnected from what we previously had to do. But deep down we are still all runners and so our minds as much as our muscles, are part of this running phenotype. The essential thing is to run period and to do it for a long time and constantly.”

Sources:

- Bernd Heinrich, Why We Run

- Bernd Heinrich, In a Patch of Fireweed

- Nick Marshall, 1982-85 Ultrardistance Summary

- Why We Run – Salomon Running TV S3 E01

- Ulrarunning Magazine, Oct 1983, Jul/Aug 1984, Apr 1988, Jul/Aug 1998, Jul/Aug 2001

- Boston Globe, May 5, 1962, Apr 22, 1975, Sep 15, 1980, Nov 3-4, 1984, May 20, 2001

- Fort Collins Coloradoan, Nov 29, 1973

- Tampa Bay Times (Florida), May 26, 1979

- The San Francisco Examiner, Oct 29, 1979

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Dec 15, 1979

- The Los Angeles Times, Mar 20, 1980

- Des Moines Tribune (Iowa), Apr 23, 1980, Jun 25, 1981

- Green Bay Press-Gazette (Wisconsin), Apr 23, 1980

- The Burlington Free Press (Vermont), Oct 25, 1981, Sep 11, 1983, May 27, 1984, Apr 16, 1986, Oct 30, 2003, Apr 19, 2009

- The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), Feb 27, 1984

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), May 22, 1984

- The Jackson Hole Guide (Wyoming), Aug 16, 1984

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Aug 28, 1984

- Daily News, (New York City), Nov 20, 1987

- Rutland Daily Herald (Vermont), Feb 7, 2002

- The Brattleboro Reformer (Vermont), Oct 21, 2002