Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:28 — 24.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

(Listen to the podcast episode which includes the bonus story about my love for the Grand Canyon, and the 1,000 miles I’ve run down in it.)

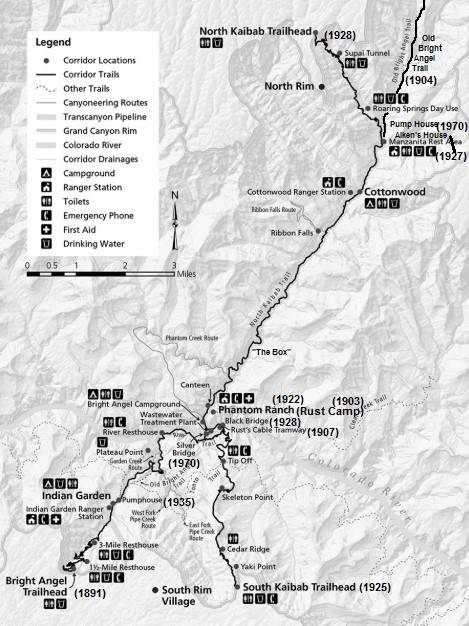

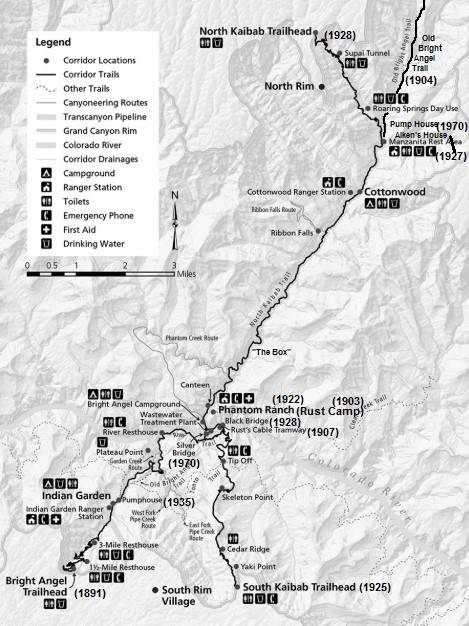

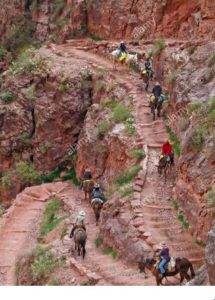

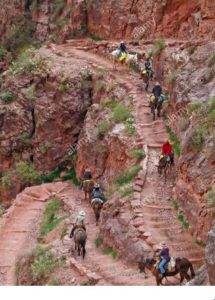

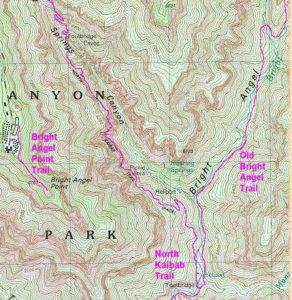

Crossing the Grand Canyon on foot is something many visitors of the spectacular Canyon wonder about as they gaze across its great expanse to the distant rim. Crossing the Canyon and returning back is an activity that has taken place for more than 125 years. Each year thousands of people cross the famous canyon and many of them, return the same day, experiencing what has been called for decades as a “double crossing,” and in more recent years, a “rim-to-rim-to-rim.”

Crossing the Grand Canyon on foot is something many visitors of the spectacular Canyon wonder about as they gaze across its great expanse to the distant rim. Crossing the Canyon and returning back is an activity that has taken place for more than 125 years. Each year thousands of people cross the famous canyon and many of them, return the same day, experiencing what has been called for decades as a “double crossing,” and in more recent years, a “rim-to-rim-to-rim.”

In 1891, crossings of the Grand Canyon using rough trails on both sides of the Colorado River, in the “corridor” area, were mostly accomplished by miners and hunters. Double crossing hikes, in less than 24 hours started as early as 1949. More were accomplished in the 1960s and they started to become popular in the mid-1970s. Formal races, for both single and double crossings, while banned today, are part of ultrarunning history. This article tells the story of many of these early crossings and includes the creation of the trails, bridges, Phantom Ranch, and the water pipeline

| Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

Introduction

When this history story starts, there was no Grand Canyon Village, no Phantom Ranch at the bottom, and these trails didn’t exist. There were few visitors to either Rim because they lacked roads and there were no automobiles yet. It is believed that Native Americans crossed the Canyon for centuries in many locations up and down the canyon and early miners used many places to cross, including the Bass location. I have run double crossings using the Grandview Trail (twice) and Hermit Trail, so there are many possibilities. This article will concentrate on the corridor region near Grand Canyon Village where most modern crossings are taking place.

Creation of Bright Angel Trail (South Side)

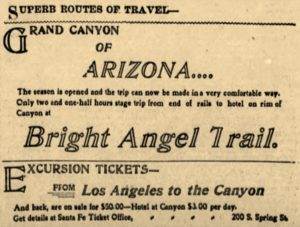

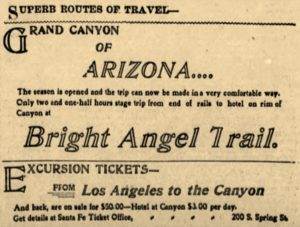

The upper part of Bright Angel Trail, coming down from the South Rim, was originally a route used by the Havasupai to access Garden Creek, 3,000 feet below. In 1887, Ralph Cameron (1863-1953), future US senator for Arizona, prospected and believed he found copper and gold near Indian Garden. The original idea for a trail was for mining. Work began on December 24, 1890 and it would take 12 years to complete. In 1891 Peter D. Berry (1856-1932) obtained rights for the trail, including collecting tolls.

By 1892 it was called the “Bright Angel Trail.” It cost about $100,000, and at its height was worked on by 100 men. How did the trail get its name? This is a subject of legend and folklore. One story was told by “Captain” John Hance (1840-1919) who came to live at the canyon in about 1883 and was famous for his stories and yarns about the canyon. He said that a beautiful girl who the men thought looked like an angel came to stay at the canyon who would descend often down the trail. One day she never came back up and wasn’t seen again. The truth is that John Wesley Powell (1834-1902) named the creek as a contrast to another creek name “dirty devil.”

To build what is known as Jacob’s Ladder, workmen had to swing down with ropes 100 feet to drill holes in the rock which blasting powder was inserted. Thankfully there were no bad accidents during construction. One worker said, “Fifteen hundred feet of the trail known as the “Devil’s Corkscrew” had to be blasted out and this is what I consider the best engineering feat of the work.

The greatest hardship was getting provisions to the canyon from 75 miles away. Teams of horses became snow-bound and the workers ran out of provisions. They had to use snowshoes to to bring the stuff in. From the rim it then had to be packed down to the workers. There was no water on the rim and it had to be hauled from 18 miles away. They had to sleep at times on the steep cliffs using a tarp as a blanket because there was no room for a tent, and would wake up in the morning covered with a foot of snow. The work was so hard and conditions so poor, that it was hard to keep men employed.

The first known double crossing hike occurred in 1891. Dan Hogan (1871-1935) and Henry Ward went down the rough miner’s trail, crossed the river and made their way up Bright Angel Canyon to the North Rim. They then returned by the same route. In 1892 evidence that the ancients lived along the trail could still be seen half way down. Cliff granaries existed with doors about 18 inches by 12 inches. In 1896, Sanford Rowe who owned property on the rim was hard at work leading a “large force” of men improving the trail. It was believed the tourists could start using the trail the next year. A hotel was in the plans to be built at Indian Garden.

The main motivation at that time to descend into the Grand Canyon was to prospect. In 1899, William F. Hull led a company of prospectors down Bright Angel Trail. He said, “We packed our effects, including our boat, on horse.” The boat was made out of canvas, about fourteen feet long. “On getting to the river, at the bottom of the steep inner gorge, we put it in shape and two of us embarked. With that frail, canvas-covered boat it took all our nerve and every faculty on a strain to keep afloat and avoid the constant whirlpools and mad counter-currents on every side. More than once we thought for an instant that our time had come.” On reaching the north side, they claimed to find a ledge with a vein of copper nearly 100 feet wide located about 1,000 feet above the river. Later that year, W. Frank Russell lost his life trying to cross the river in a canvas boat in an attempt to prospect the supposed vein. He couldn’t swim and he was last seen clinging to the capsized boat. His remains were found several years later buried in a sand bar several miles down river.

In 1900, the railroad was completed far enough to bring tourists from Williams to the Grand Canyon, including some of the trip in a stage-coach for a price of $10. They could descend into the canyon on mules or horses.

By 1902 the train had made its way clear to the canyon where a small temporary hotel existed at the head of Bright Angel Trail that could accommodate 35 people. A much larger one was in planning stages (El Tovar) by the railroad. “Finally we reached the canyon about 10 o’clock at night. The porters of the Bright Angel hotel met the train with lanterns and handcarts. Along with about sixty other passengers, I followed a flickering lantern up the hill to the hotel. I stepped into the hotel sitting room. The walls were covered with Indian blankets and skins of wild animals and decorated with deers’ horns and pictures of the canyon. I was told that owing to the crowded condition of the hotel I would have to sleep in a tent.” Horse and mule trains brought tourists down to Indian Garden and Plateau Point. “There, with the subdued roar of the water in our ears, we ate our lunches and climbed about the rocks and chased the nimble lizards.”

By 1903 traveling down to the river and back in one day either by foot or by horse was possible. That year, Cameron convinced government authorities that he had legal claims to the trail. He had obtained Peter Berry’s rights for the trail about 1902. The Secretary of the Interior granted Cameron exclusive rights to Bright Angel trail, enabling him to make it into a toll road. “This concession was granted Mr. Cameron because of his having located the trail previous to setting aside of the Grand Canyon forest reserve, and complied with territorial laws.”

Cameron soon charged a toll of one dollar to use the trail, plus fees for drinking water and to use outhouses at Indian Garden, bringing in about $1,000 per month. Immediately legal challenges reached the courts from others to prove they constructed major portions of the trail, not Cameron. In May, 1903, District Court in Flagstaff ruled in favor of Lombard, Goode & Co’s. claim but by the end of the year another case ruled in favor of Cameron. The railroad fought on in the courts to try to prevent Cameron’s tolls, but in 1904 the Department of Interior confirmed Cameron’s rights to the trail. Coconino County eventually gained rights to the trail and received toll revenue.

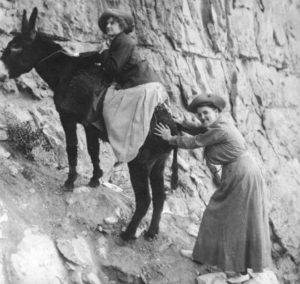

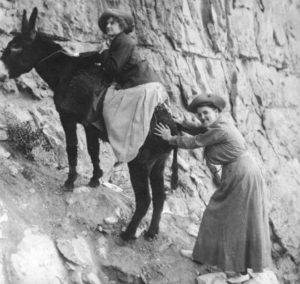

A 1905 description of traveling down the Bright Angel Trail to the Colorado River and back was provided by a lady who went by horseback to Indian Garden, and a little further, then by foot to the river and back. She wrote, “A strong person accustomed to walking can easily make the round trip on foot, but women rarely undertake it. A horse for the upward climb is almost a necessity. The trip from the mesa [rim] to the river is a trip of six or more hours. At “Jacob’s Ladder,” which is a flight of steps cut in the stone, we dismounted, leading the animals down. In three hours we made “Indian Gardens” a little camp is situated for the accommodation of the travelers consisting of a good-sized dining room and several tent houses, furnished with Navajo rugs and little white cots.”

“Resting a few moments, we started onward to the river. This portion of the trail is much steeper and difficult. In places one scrambles and slides down an almost perpendicular wall, the animals being abandoned at a zigzag place called the “Devil’s Corkscrew.” The Colorado River was something of a disappointment to me as I hoped to see a specimen of the raging fierceness of its rapids or waterfalls. Here instead it is as turbid as a sea of frothy mud and uninteresting.” Returning to Indian Garden they had a “fine dinner furnished us by Japanese cooks and waiters,” and then went by horse back up to the rim.

Bright Angel Trail on the North Side

In 1897 F.S. Burt and Sam Hubbard Jr. ventured across the river and explored up Bright Angel Canyon and discovered Roaring Springs. They reported “the discovery of a big water fall, north of the river several miles. The water seems to pour out of a cave from a perpendicular side of a high wall of red rocks and judging from the distance it was thought it must be fully fifty feet wide.”

In 1902, Edwin “Dee” Woolley, the Mormon leader in Kanab, Utah, started to pursue a vision to allow travel across the Grand Canyon. To descend into the canyon from the North Rim, he chose to try a route down from the head of Bright Angel Creek, about five miles northeast of the current North Kaibab trailhead (located at the head of Roaring Springs Canyon). He and two others explored. There was no trail used by humans there. They found some game trails that helped them descend to the creek bottoms and concluded that a trail could be made.

Later in 1902 a group of surveyors, led by Godfrey Sykes, descended the same route to consider building an facility to generate electricity. They cleared brush, logs, and boulders. Once down to the wider valley. they continued to follow the boulder-filled Bright Angel Creek to the Colorado River, crossing the creek 94 times along the way and mapped the route.

A serious proposal was brought forward in 1902 to dam Bright Angel Creek probably at “The Box,” to generate electricity to be taken to Flagstaff, Arizona. A company was formed, the “Grand Canyon Electric Power Company.” It was estimated that the plant would be up and running by 1903.

Also in 1902, an separate survey of Bright Angel Canyon took place by the U.S. Geological Survey, led by François Émile Matthes (1874-1948). His team was surveying many sections of the canyon and its rims. In the fall of that year they reached the top of Bright Angel Canyon and were surprised to see two men, Sidney Ferrall and Jim Murray coming up with a burro. They had crossed the canyon and planned to return. Two of the survey team went down ahead to cut brush and roll off logs and boulders for the survey pack train. The entire team began the descent on November 7, 1902. “So steep was it in certain places that the animals fairly slid down on their haunches.” By noon they made it down to the junction with Roaring Springs Canyon. They crossed Bright Angel Creek 94 times and made their camp for the night prior to entering “The Box.” It rained that night and the next day they looked back up to the North Rim and saw that snow had fallen. They spend several days in Bright Angel Canyon mapping it out and then went to the Colorado River where a prospector kindly let them use his boat to cross and head up to the South Rim.

As work progressed on the electrical proposal, a man was posted year-round at Bright Angel Creek to watch over the power company’s interests. In 1903 a company man came to relieve a watchman. They met up at Indian Garden on the south side of the Colorado River, and the first man went back down with his replacement to show him where the camp was. They attempted to cross the River at “Cameron’s ramp”, likely near present-day Silver Bridge, but they were never seen again and the burros on the other side were still waiting for them. In 1904 Andy Connon spent nearly a year at Bright Angel Creek as a watchman. For three months of that time he didn’t see a single person. Power plant plans were soon abandoned.

Woolley formed the “Grand Canyon Transportation Company” in 1903 and petitioned the county for a toll road on the Rim and down into the Canyon. Work started in 1903 “hacking out some rock and vegetation. The rough trail zig-zagged down a steep ridge, two miles to the creek bottoms.” The entire trail soon was called “Bright Angel Trail,” the same name used for the trail on the north side of the Colorado River.

In 1904, William W. Bass (1849-1933) petitioned to have a mail route established using the Bright Angel trails to deliver mail to a Ryan, a mining town that existed near present-day Jacobs Lake.

In 1905 Woolley was granted a Forest Service permit for a right-of-way, but it couldn’t be a toll road. He also received rights to establish a camp located near the mouth of Bright Angel creek that was located about a half mile closer to the River than present-day Phantom Ranch. Woolley’s hope was that it would become a tourist camp.

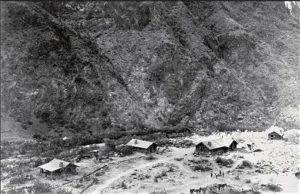

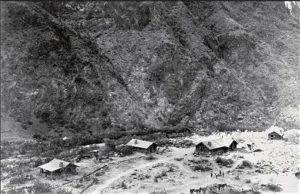

Woolley’s son-in-law, David D. Rust (1874-1963) joined the company in 1906 and went down into the Canyon to work as the manager and foreman with those who had been building the trail. Day after day they chipped out a graded trail with pickaxes on the steep side hills. By the end of the year there was a “suitable” trail in place from the North Rim to the Colorado River and the workers celebrated by taking a “plunge” in the River. The nearby camp became named, “Rust Camp.”

Rust and his crew improved “Rust’s Camp” with irrigation ditches and then planted cottonwood trees by transplanting Cottonwood branches cut from trees found up Phantom Creek. Adventuresome tourists would initially come over the Colorado River by boat to visit the camp and go part way up the trail into the “The Box.”

Crossing the Colorado River

In 1905 a “cable ferry” started construction to float both humans and horses across the Colorado River, a length of 500 feet. James S. Emmett of Lee’s Ferry oversaw its planning. The hope was, that travelers to and from Utah could use this crossing and go up Bright Angel Canyon to the North Rim instead of all the miles to the ferry crossing at Lee’s Ferry up the River. A large cable was brought down from the North Rim and the ferry system was completed in October 1906, going across near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek. Hunters started making use of it to get to the North Rim. For whatever reason, the cable ferry did not operate very long, probably because of safety concerns.

During the fall of 1905, a large hunting party including some of the city leaders from Williams, Arizona crossed over to the North Rim to hunt. Their company included 14 riding and pack animals which were all swum across the river. A boat was rowed across 57 times to bring everything across. The trail up to the North Rim was in poor shape from storms, so men at Rust’s Camp were sent ahead to make improvements. Hip boots were worn because of all the Bright Angel Creek crossings that were necessary. “The water was a rushing torrent in places and mad travel difficult. The trip was cut short on account of a snow storm.” The company killed seven deer.

To get more tourists to the camp, in 1907, Wooley and Rust constructed a cable car system across the Colorado River allowing visits from the South Rim. The “cable tram” was about 400 feet long and about 40 feet above the water. The car with passengers was moved over to the north side by gravity and using a crank. If the car is on the wrong side, an operator would go over on a narrow seat with one pully to retrieve the car. A gasoline engine was installed in 1909 but would break down often. The cable car was a key attraction in the canyon, but there was not always an operator stationed there. Most visitors weren’t daring enough to operate it themselves, so instead of visiting Rust Camp, they would return to the South Rim.

Linking the North and South Bright Angel Trails

To truly establish trans-canyon travel, what remained was to improve the trail on the south side from the tram crossing up to Cameron’s Bright Angel Trail at Indian Garden. Travelers were coming down Pipe Canyon and then going along the rough shoreline of the River to the tram. Cameron was in favor trail of the improvement plan but would not provide any money or resources to do the work, so it was up to Rust. Rust knew that blasting a trail above the south bank would involve difficult blasting, so in 1908 he turned his attention to a prospector route called “Wash Henry Trail” that went up the steep canyon above the tram to a place called Tipoff. (Present-day South Kaibab winds its way up to Tipoff). The trail would then cross the Tonto Platform west to Indian Garden. This connector trail was completed in 1909.

Rust Camp

By 1908, Rust Camp had six tourist tents, a cook tent, and herd of sheep. The following year, Rust ran into famous naturalists John Muir and John Burroughs coming down the South Bright Angel Trail and invited them to visit his camp. Rust wrote, “They were real people. We would sit down every hundred yards chatting and observing.” Rust stayed busy shuttling visitors from Rust Camp to the North Rim and back. It was the first year that the camp was open all season and hosted a few groups each week.

One of the very early Grand Canyon runs took place in 1910. A rich woman was with a group on an outing on the north side of the canyon. An important telegram needed to be delivered to her. During the heat of July, a young man working at Kolb Brothers Photography volunteered to deliver it. The woman’s traveling group had a two-day head start on him, but he ran down into the 100-degree canyon, crossed the river in the cable car, fording Bight Angel creek repeatedly, and reached the company somewhere up the canyon in only 6.5 hours.

In 1912 Ralph Cameron sold 35 mining claims near Indian Garden and Devil’s Corkscrew for five million dollars to a investors in Pennsylvania. It was reported that the the investors “intend to place immense milling plants on the ground and construct an electrical plant” at Indian Garden. The deal fell through. In 1913 Cameron was mining platinum near Indian Garden and hoped to still lease mining rights to the Pennsylvania company, but not with a plan to build huge plants. As it turned out the ore was tested carefully and no platinum was found.

Also in 1912, improvements were being made on the Bright Angel trail in the area known as Cape Horn to create a tunnel to make the trail safer. The workers prepared five blasts of dynamite. Four went off, but the last one didn’t. After waiting fifteen minutes, Charles Bell decided he would go up for dinner and come back later to check on the blast. While over the blast area, the charge went off, throwing Bell into the air, tossing him over an 80-foot cliff. Rescuers reached him but he only lived for about an hour more.

In 1913, former President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) and his sons visited Rust camp, coming over in the cable car, and was thrilled to be in the inner canyon. The crossing over the river took place during a terrible thunder storm and all the part was terribly drenched. Soon after, they reached Rust Camp was unoccupied. Rust was away at the time. Guided by two cattlemen, Roosevelt went on with a hunting party to the North Rim to hunt mountain lions for several weeks. Hundreds of the lions roamed the Rim at that time along with an estimated 15,000 mule deer. While already in the Canyon, there was some controversy whether Roosevelt had a proper hunting permit but Washington quickly granted a special permit “for scientific purposes” to let his party “bag as much game as desired.”

Because of the visit, soon Rust Camp was renamed to “Roosevelt Camp.” Despite the attention this visit caused, the camp still didn’t receive heavy tourist traffic. The trail was rough from the north, and the cable car was pretty scary.

In 1919 a camp was established on the North Rim called the “Wylie Way Camp,” which attracted automobile tourists. It later became known as “Bright Angel Camp.” More people from the Utah side started to visit Roosevelt Camp from the North Rim.

By 1920 various guided trips were available for the general public to ride down into the Canyon. From the North Rim for $5 you could ride a horse down to the river and back on a three-day trip. Bedding and provisions were another $2.50. From the South Rim if you wanted to go clear to the River and back, in one day, for $5, you would leave on a guided mule train at 8:30 a.m., reach Indian Garden, go on foot to the river using the rough trail to Pipe Creek. You would return to the South Rim at 5:30 p.m. You could go on foot all the way down, but to ride a mule back up from Indian Garden was still $5. There was even an option to do a Hermit-Tonto-Bright Angel Loop, two days and one night for $23.25 including meals.

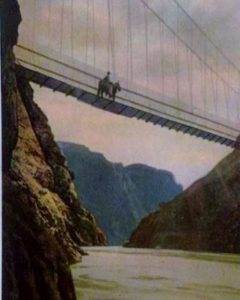

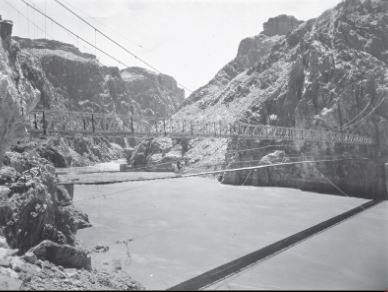

The Swinging Suspension Bridge

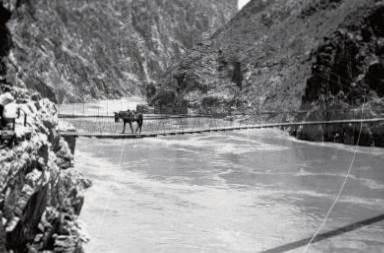

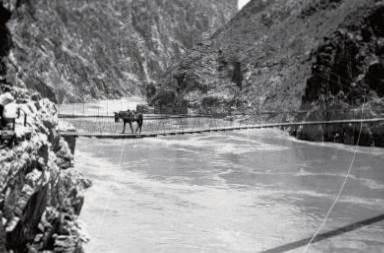

The National Park Service built the first bridge in the Canyon across the Colorado River in 1921. It was called the “swinging suspension bridge” and was built near the present-day Black Bridge location. Because it would swing, it could only handle one mule at a time and was only 13 feet above the highest recorded water level.

A 1,200 pound cable needed to be brought down the Bright Angel Trail by mules. They first rehearsed the trip carrying down ropes of the proper length. The cable was successfully brought down on eight mules roped together. Once the bridge was finally completed, The Park Service reported, “The bridge has linked the two sides of the Grand Canyon and makes possible trans-canyon travel.” The River trail did not exist at that time to reach the bridge area. To get to the bridge, there was a trail used at the upper end of Pipe Creek

Early Single Crossings

After the bridge was finished, a party on horses attempted a Canyon crossing ride in late September, 1921. “One of the horses refused to step on the bridge, which swayed too much to suit his fancy, and laid down. They had to drag him on.” The rough trail up to the North Rim was a real problem because of the narrowness of the trail. But they made it all the way.”

Canyon crossing hikes were now possible on foot the entire way. In 1921, Milo D. Gibson went from North to South in four days. It took him three days to reach Roosevelt Camp. Coming down the Bright Angel Trail from the North Rim was rough because it was “seldom traversed except by hardy hunters.” He described going down the trail, “In order to follow it, the creek has to be forded again and again, the depth ranging from knee-deep to waist-high. The drinking water was good at first and then became poor.”

Before 1921, the manager of the El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim explained why there were still few crossings. “The reason is that the trail up Bright Angel Creek is too difficult. It is too much to attempt except by a seasoned athlete who has no objection to strenuously roughing it. The almost ice-cold creek has to be crossed 117 times between the Colorado River and the North Rim and this in itself is no picnic.”

In 1921, Bonnie Gray, an very accomplished athlete and famous stunt rider from California, claimed that she had run across the canyon using the Bright Angel trails in 6:25. She said she “believes that this feat will never be equaled by a woman.” Given the rugged nature of the trail, and all the creek crossings needed at that time, the published time should not be believed.

Phantom Ranch

Roosevelt Camp was renamed to Phantom Ranch by Mary Jane Colter (1869-1958). Major construction of the Ranch began in 1921 under her direction. It opened the next year with four cabins, a lodge with a kitchen and dining hall. Work went forward to improve Bright Angel Trail to the North Rim.

The Park announced that “the government will put the trail up Bright Angel Canyon into shape for easy traveling by women and children. Half way up Bright Angel Creek toward the north rim, another camp will be built to be named Ribbon Falls camp.” Because the trail section through “The Box” would often flood, it was raised above the creek bed which eliminated many of the creek crossings.

The Kaibab Trail (south and north)

Work began in 1924 on a new trail coming down from the South Rim at Yaki Point as an alternative to the Bright Angel Trail toll trail. This new trail was first named “Yaki Trail” or “Yaki Point Trail” and would eventually be named, “Kaibab Trail.” Previous to this, work was underway in 1922 on the “Cable Trail” that ascended from the Swinging Suspension Bridge to west of present-day Tipoff. During the construction work on the Cable Trail in 1922, Forman Rees Griffith (1872-1922) was descending a rope after some rock had been blasted away. Loose rock from above fell on him and killed him. He left behind a wife and five children in Fredonia, AZ. He was buried near the trail along the north side of the River. His burial-place and monument can still be seen from the trail.

In 1925 the South Kaibab Trail was finished at a cost of $73,000 with the trailhead at Yaki Point. Promotions for the trail included, “The new trail will be by far the most scenic trail in the canyon as it winds its way down the walls along a ridge jutting out into the abyss from which magnificent views of the canyon may be had both to the east and the west.” Tourist traffic increased to Phantom Ranch. Two-day mule trips across the Canyon were taking place using the South Kaibab Trail and the Bright Angel Trail going up to the North Rim.

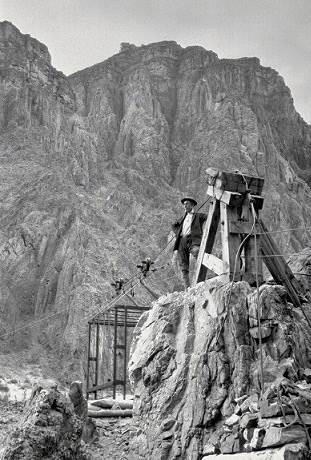

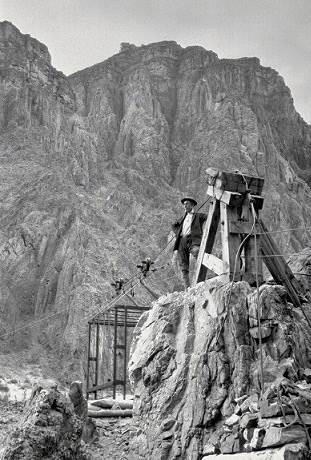

In 1924 work started on the North Kaibab Trail that would bypass the rough “Old Bright Angel Trail” and head up Roaring Springs Canyon to the North Rim. When it was proposed, engineers said “it can’t be done” but the trail work was started. Work was mainly performed on the trail during the winter because of extreme heat. Work required much blasting and hammering, including creating the 20-foot-long Supai Tunnel. In 1927 a cable conveyor system was put in from the North Rim to Roaring Springs to more quickly bring down equipment for trail building. In 1928 the trail was finally complete. Reports included, “For those looking for the ‘big thrill,’ the new Kaibab trail will give it, for beyond all question of doubt, it is the most spectacular horse trail in the world.”

As tourist traffic continued to increase to Phantom Ranch, a new bridge was needed. High winds had capsized the Swinging Suspension Bridge more than once. Construction began on a new bridge on March 9, 1928 with nine laborers who established their camp on the confluence with Bright Angel Creek. The crew soon grew to twenty. The location for the bridge was chosen to be about sixteen feet directly over the current bridge. A tunnel on the south side was excavated running 105 feet. In 1929 what became known as “Black Bridge” was complete, and originally called the “Kaibab Suspension Bridge.” It was rigid, wider (five feet), and higher than the first bridge.

The Bright Angel Trail on the south side received an important face lift in 1932. The Devil’s corkscrew area was a constant problem from rock fall and wash outs. Below Indian Garden, the trail was moved to follow Garden Creek and then to a totally new Devil’s corkscrew. (Today you can still follow the old unmaintained trail if you know where it is.) The Park Service reported, “Many of the sharp zigzags have been eliminated, grades have been greatly reduced, and a heavy rock guard wall has been placed along the outer edge of the trail. Even the most timid now should feel no hesitancy in taking this scenic trip.”

In 1938 work took place to improve the trail from the bottom of the new Devil’s Corkscrew through Pipe Creek to the Colorado River. About 75 percent of the trail work involved carving into the cliffs to raise the trail up above the high water mark. It was completed in 1939.

Visitors to Phantom Ranch

Royalty descended into the Canyon in 1926, Prince Gustaf Adolf (1906-1947) of Sweden, heir of the throne. His group of 18 went all the way to Phantom Ranch on a July day when it was 110 degrees at the bottom. The Prince, age 20, immediately went off alone to swim in Bright Angel Creek. (The prince was killed in a plane crash in 1947).

In 1929 a deer caused quite a stir crossing the Colorado River. The deer had free reign of the corridor trail area. It was tame, had been brought over from the North Rim by the park and raised on the South Rim in the village. One day it was below Phantom Ranch with her two fawns, she jumped in the River, was taken by the current, and came over to the shore at Pipe Creek. Her fawns didn’t follow but went up river and crossed at the tamer waters near Black Bridge. The fawns went up South Kaibab Trail to the Tonto Platform. The mother went up Pipe Canyon. Somehow they met up at Indian Garden.

Also that year a colony of beavers nurtured by the Park in upper Bright Angel Canyon migrated down to Phantom Ranch and started to cut down many of the beautiful shade trees that had been planted there. They sent the beavers home but they kept returning for many years.

In 1930, 100,000 fish eggs visited the ranch, brought from Montana. Rangers took the eggs on their backs from the ranch and planted them in side streams (Phantom Creek, Wall Creek, and Ribbon Creek). Fishing was excellent down there.

A horse named “Old Bob” pulled a four-horse coach for more than a decade on the South Rim. He pulled kings and presidents. In 1922, as faster automobiles replaced his coach, Old Bob lost his job. Instead of being auctioned off, an official at the transportation company let “Old Bob” retire to Phantom Ranch to graze along Bright Angel Creek. In 1936 after nine years he was still an attraction at Phantom Ranch and was 31 years old.

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) improvements

The CCC constructed the “River Trail” that was carved out of the rock on the south side of the Colorado River. It then was much shorter and easier using the Bright Angel Trail to get to Phantom Ranch. They also constructed the Clear Creek Trail, built bridges across Bright Angel Creek, and put up stone walls that are still seen on the North Kaibab Trail. Up on the North Rim they constructed a ski/toboggan run and tennis courts that could be flooded in the winter for ice skating.

The CCC built a swimming pool at Phantom Ranch which was used until 1972. The abandoned telephone line that today is seen along the North Kaibab Trail was also their handiwork. Over the years the line was unreliable because of storms in the winter and snow. In 1942 a “radiotelephone” started to be used for improved communications.

In August 1936, a massive flash flood sent a wall of water down Bright Angel Creek that was said to be 16-feet high at one point through “The Box.” It did extensive damage to the trail going up the canyon and destroyed the water pipeline going to Phantom Ranch. CCC enrollees went to work repairing the damage.

There was great concern at the end of 1937 when 12 members of the CCC became marooned at a forest ranch near the North Rim with 15 others because of an unexpected very deep snow storm. They had to survive on the food on hand for two months. When there was only food left for a few days, the CCC member desperately broke a trail to the rim and was able to descend down and rejoin their main group at Phantom Ranch. The remaining contractors also made it out to rescuers who took them to Kanab.

Early Double Crossing

In 1949 Harry Brown, an employee of the Forest Service, said he ran what is believed to be the first double crossing in less than 24 hours. There were others who accomplished this in the 1960s. But it wouldn’t be until the 1970s that this activity really took hold.

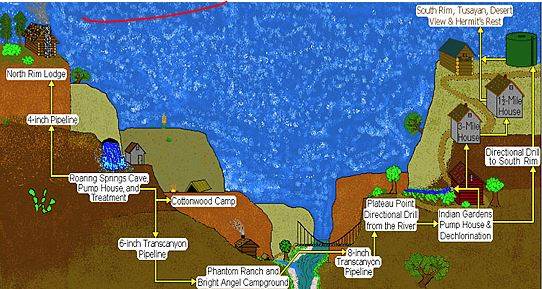

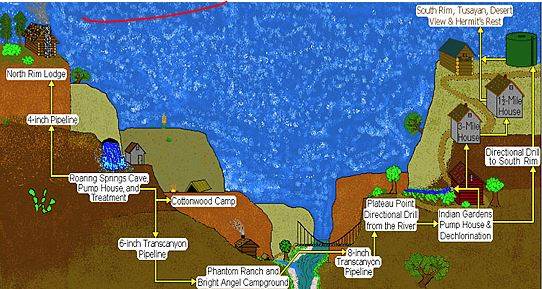

Pipeline and Silver Bridge

As far back as the 1930s, the South Rim water supply for the hotels and settlements was being transported from Flagstaff, 100,000 gallons daily. In the mid-1930s, about 150,000 gallons per day started to be pumped up from Indian Garden but over time that wasn’t enough.

In 1965 a trans-canyon pipeline began construction to take water from Roaring Springs to the South Rim. But in 1966 a massive flood in Bright Angel Creek destroyed much of the pipeline under construction and closed Phantom Ranch for several months. It also tore down trees and destroyed much of the North Kaibab Trail, campgrounds, bridges, and buildings.

From the North Kaibab Trail, you can look up and see water coming out of caves. A series of five rock dams were built inside the cave complex to collect water. The cave’s average flow of water is 5.8 million gallons per day. Seventeen percent of the spring water is diverted into two intake pipes. The rest of the water free-flows out the east cave entrance down to Roaring Springs Creek. At the Roaring Springs pump house, sediment is removed, and chlorine gas is used to purify the water. Some water is pumped up to the North Rim and one million gallons of water per day travels by gravity all the way to the Indian Garden Pump Station on the south side of the River. The pumps there push it the rest of the way up to the South Rim.

Aiken’s House

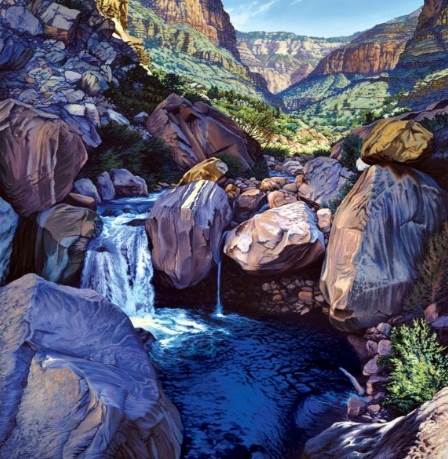

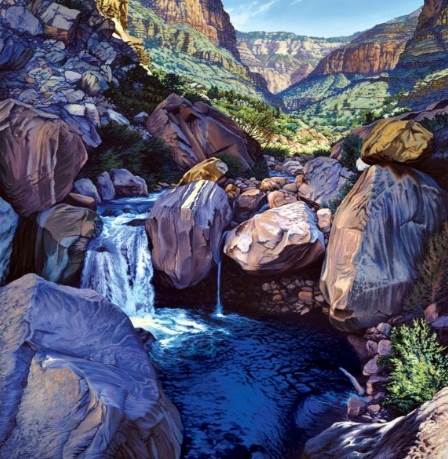

It took Mary Aiken about three years to totally feel comfortable living down in the canyon, but one day while walking by the cliffs with the light streaming in, she suddenly felt a part of it. She said, “Wow, I’m so lucky. I never want to leave here. To know it is to love it. It has made me strong living here, inside and out.” She also said, “I don’t tell strangers that I live at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, it just confuses them.”

Aiken’s children grew up in the canyon and loved it. When asked if the kids missed out on normal life, Bruce replied, “Yeah, but you know, you can’t have everything. The kids that lived in town didn’t have what my kids had. They had nature, full connection to nature, fabulous free reign. My son never wore shoes until he was five years old. He caught trout in Bright Angel Creek with his bare hands and they met interesting people from all over the world on the trail.” The kids would set up a lemonade stand for hikers and made very good money. They also invited tourists to dinner, resulting in dinner guests nearly every night. Little Shirley Aiken once wrote, “As the cheerful sunshine peeks over the Canyon walls, the violet-green swallow sings his songs. I am so lucky to live down here.” Silas Aiken, when age seven said, “I lived down here before I was born.”

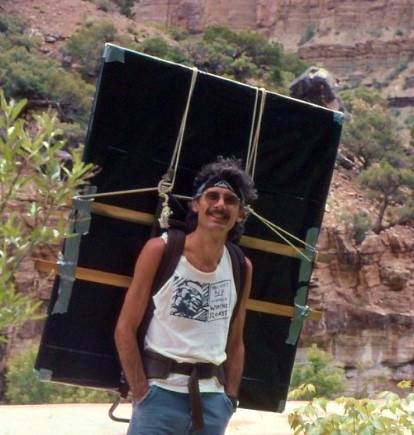

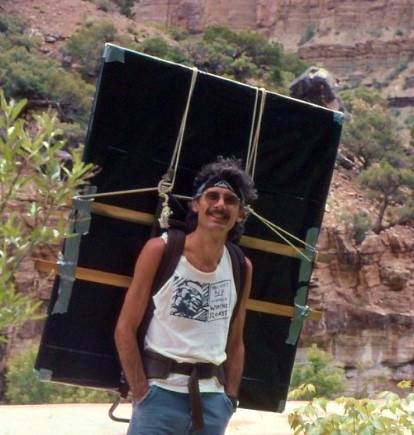

When Bruce Aiken was asked why he lived down there for so long he replied, “I’ve never been a guy who cared about shopping or Wal-Mart or movie theaters or crowds. Life in the Canyon got better every year.” They of course had no TV and mail came only every two weeks, but they could listen to three AM radio stations, only when they faded in at night. In the mornings. Because the NPS helicopter wouldn’t take his paintings out the canyon, he rigged a device on his back. In 2006, Aiken finally moved out of the canyon because he became eligible for retirement. The Aikens decided that they needed to do other things. He wrote a book and established a studio. In recent years the pump house was automated, and a caretaker was no longer needed. The Aiken’s house was converted to a ranger station and restrooms added. The location was renamed to “Manzanita Rest Area” in 2015. Hopefully when more Grand Canyon runners stop to fill up their bottles at Manzanita Rest Area, and look at the ranger station, they will think of the Aikens who lived there for 33 years.

Modern Crossings Begin

In 1957 the Southern Arizona Hiking Club began annual rim to rim hikes led by Charles. A Thornton (1912-1993). In 1960 Blind boys from a school for the blind in Tucson, Arizona would also participated, That year, 22 hikers participated including seven blind boys. It was thought to be the largest group at that time to ever hike across the Canyon. The goal was to complete the crossing in 12 hours. Thornton said of the boys, “They seem to feel, if they can cross the Grand Canyon on foot in one day, they can do almost anything.” The hiker first to finish that year was Dave Gross, in 9:35.

In 1961, 14 club members hiked. Eber Glendening (1934-1997) and Bill Faust accomplished a double crossing to “prove that it could be done.” In the heat of mid-June, they stopped at each Bright Angel Creek crossing to dunk their heads in the water. They had stashed some food and a flashlight at Phantom Ranch, but it all was stolen by the time they returned. Some tourists generously invited them for dinner. They finished in 20:40. Two others from the club finished a double in 1962, Ted Marley (1927-2014), and Joyce Wickham. On Memorial Day, 1964, Charlie Thornton, age 52, ran a double crossing. His first crossing took about 6:30. He rested for a half hour on the North Rim and then ran back down. He finished in 15:55 which was likely the fastest known time.

In 1974 Bill Emmerton (1900-2010), a very experienced marathon runner from Australia, received newspaper attention when he ran across the Grand Canyon in August. He had a rough time with the trails and finished in a slow 7:45. He had planned to do a double crossing but stopped. He said, “This was the most difficult run I have made during my entire life.” Rangers cheered him at both the start and the finish.

In October 1974 Jerry Jobski, a world class marathoner, and the cross-country coach at Westwood High in Mesa, Arizona set the fastest-known-time for a south-to-north crossing. He crossed in 3:07:27. Chuck LaBenz also ran, finishing in 3:15:44. Jerry had previously run a single crossing in 3:08.

Also in the mid-70s, Paul Julien, a scout master in Flagstaff accomplished a sub-24-hour double crossing with a friend. They crossed south to north in less than 8 hours. They were just aiming to finish in less than a day so took naps along the way and finished in 22:59. Boy Scout Troops in the Flagstaff, Arizona area started to award patchs to scouts who hiked across the Canyon and back.

In 1979 a group of five runners from Houston planned to run across south to north and then back the next day. All went well until about mile 22 on the North Kaibab trail. The closed trail had a section that was destroyed by heavy spring runoff and it dropped away down a cliff. They considered running back but doing 44 miles was outside their abilities. They eventually scrambled around the damaged section and made it to the North Rim after a 9.5 hour run. The North Rim rangers were not pleased, said they could have cited them, and wouldn’t let them go back down the next day. The runners took a $298 10-minute helicopter ride back.

The Grand Canyon Races

In 1979 utrarunning legend, Ken Young, organized a group to race across the canyon, north to south. After finishing, Ken asked Wally Shiel, “Wally, what do you think of running across the canyon and back?” He replied, “Ken, I don’t know. We’ve just been running for four hours and I’ll have to think about it later.” These thoughts would lead to a double crossing

The race grew each year and in 1981 had 101 starters and they all finished. Two groups started ahead of the main group. Jennifer Hesketh reported, “In the early morning semi-darkness, the runners streamed down the rocky, muddy and washed-out trail. The climb out at the south end was muddy and slippery too. Some people from the South Rim supplied the heretofore unheard of, but wonderfully appreciated four aid stations, with water.” Allyn Cureton finished in 3:06, breaking the fastest known time, and Linda Donkelaar finished in 3:40.

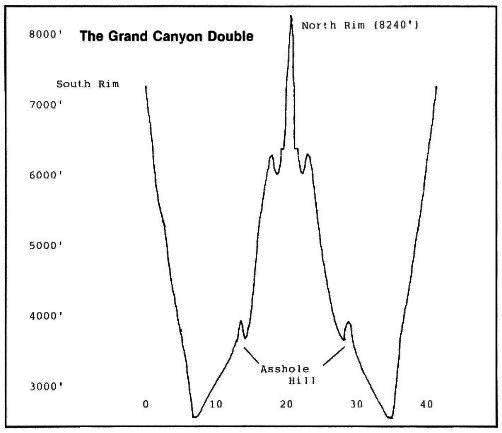

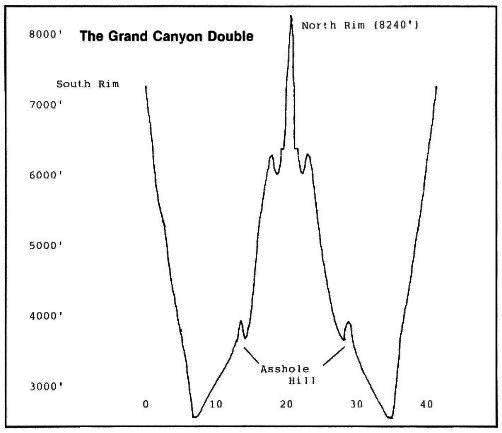

On November 9, 1981, Ken Young and Jennifer Young, of the Southern Arizona Hiking Club, organized the first Grand Canyon Double Crossing race starting at the South Kaibab trailhead. Nine brave runners participated with five taking an early start at 3:46 a.m. The others started at 6:30 a.m. The North Rim was pretty washed out in places. Jennifer Hesketh reported, “The race really began on the return leg, with most people letting out the stops, and returning at a brisk pace. But everyone slowed for what is affectionately known as “Asshole Hill, which is where the trail for some unexplained reason leaves the creek and climbs up over a small hill right where it shouldn’t. Allyn Cureton won in 7:51:23 which was a fastest known time for a double crossing.

In October 1982, the “Grand Canyon Single Crossing” race was again held, by a different group, north to south with 116 starters finishers. Allyn Cureton won in 3:16. Rebecca Felton won among the women with 4:53. There were complaints from hikers that this group had poor trail etiquette and there were reports that they were disruptive to others in the restaurants and other facilities on the rim.

On November 7, 1982, the Grand Canyon Double Crossing race exploded to 50 runners. Runners were warned, “The cost to haul you out should you be injured or just plain tired out could run between $75-100. You are on your own once you begin. The trail is not maintained on the North Rim part. It will be leaf strewn, washed out, rocky, and in some parts very dangerous. One section, the cliffs, is blasted out of rock and has a very sheer drop off. The last climb out can be exhausting. You must climb out if you want to go home. There are no aid station, course monitors, T-shirts, trophies, or anyone to hold your hand.”

The runners could choose between four start times from 2:35 a.m. to 6:39 a.m. The groups became congested near the turnaround at the North Rim. Rae Clark won with 7:58, with John Cappis second, finishing in 8:14. Valerie Doyle set the women’s fastest known double crossing time with 10:53. All but one of the starters finished the complete double. One runner said, “Imagine a 4 a.m. start, 6 ½ miles down a winding trail with a 4,800-foot drop in the dark. The only good things were, you could not see how really dangerous and steep the trail was and you could not gauge how incredible the return would be.”

After the 1982 races, the Grand Canyon National Park Service requested that no “formal, organized competitive events or spectator sports” take place within the park. A major television network was interested in televising a rim-to-rim run with 1,000 runners. That got the Park’s attention. The club stopped organizing a double cross race for a few years.

On November 3, 1985 a “Grand Canyon Double Crossing” was held by Fred Riemer from Utah. That year 23 runners started and 21 runners finished. They used three different starting times from 3:15 a.m. to 6:15 a.m. with near-freezing temperatures on the South Rim. The inner canyon reached a comfortable 76 degrees. All runners carried a little food and a water bottle. Most runners stopped at Phantom Ranch for a rest and lemonade. Riemer from Utah set up two aid station on the final climb. Rae Clark won with 9:04 and Cindy Suplizio from Salt Lake City, Utah set the women’s fastest known time of 10:28.

In 1986 the Southern Arizona Hiking Club again started putting on a double crossing race that would be called the “Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim 50,” with Sid Hirsh of Tucson as race director. These annual races were held in late May when it could be very hot. Thirteen started and ten finished. In 1987 the “Colorado Mountain Club” joined in the race. Twenty-six runners started along with a newspaper reporter who wrote, “We moved as fast as we could, trying not to become sudden cartwheels and spin-off into the river a mile below.” The winner finished in about 14 hours and four didn’t finish.

In the fall of 1987, a Utah version “Grand Canyon Double Crossing” was also held with 25 starters, organized by Fred Riemer of Utah. The first runners started at 3:00 a.m. and the last runner went out just after 6:00 a.m. They started at the North Rim that year. Wally Shiel’s dad provided fluids at the South Kaibab trailhead. The winner was Robert Ash of Utah and the last runner went all through the night finishing in 26:10. Wally Shiel, who had finished 71 marathons and ultras finished second in 10:05 and then kept going to accomplish a quad crossing in 24:45, the first ever to do that. As of 2018, less than ten runners had accomplished a quad, including me.

In 1989 44 runners started and 43 finished the club rim-to-rim-to-rim race. That year it used the Bright Angel trail instead of South Kaibab Trail. Hirsh was asked why he kept putting on the race. He replied, “It’s my little baby. Hikers who never considered rim-to-rim-to-rim will decide to try it. They’ll run hard. And they’ll do it.”

In 1992, the Hirsh planned to put on the 7th Annual “Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim 50” In May of that year, the Arizona Highways magazine featured a long story about the race in which the author noted, “I am hemmed in by 63 bodies, male and female, bodies that shortly will propel themselves, taking me along, toward the edge of the abyss, then turn abruptly on the narrow trail at the Canyon’s edge, and lunge into the enveloping darkness.”

The Park Service was not pleased with the article, and Park Superintendent, Robert S. Chandler wrote a letter to Hirsh stating that the race was unauthorized and required a special-use permit. The formal race was “cancelled” and changed to an informal gathering to run with Hirsh. More than 80 runners showed up for this “informal” group run with two rangers waiting. Hirsh read them all a statement that the Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim race was “no more” but he was still going to run, and any others were welcome to join him, but they were on their own. The rangers said that they had an illegal assembly, and could all be cited. Angry exchanges took place but the runners were allowed to go, once all of them gave their names and contact information. The day in May was very hot and two runners had to be rescued by helicopter and continued to monitor the runners by air. That was the last formal Double Crossing race in the Grand Canyon, which the Arizona Daily Star of Tucson critically described as “the yearly opportunity to turn the Grand Canyon into their own private [sports arena] for 24 hours.”

In the early 1990s, Scott Beck of Phoenix started to quietly organize rim-to-rim hikes/runs with friends, but each year the event grew. By 2011 it involved four tour buses full of people that left from Phoenix for a hotel in Kanab, Utah. The next morning buses would taken groups in 30-minute waves to start at the North Rim and then the buses would pick them up at the South Rim. Hundreds of people were involved. Beck instructed participants that if asked who the organizer was, that they shouldn’t mention his name. But eventually someone needed to be rescued and word got out to authorities. An article was published on nationalparkstraveler.org that explained that there were nearly 300 participants in 2014. It was the 23rd annual event. That day there were long lines at the Phantom Ranch canteen and the wastewater treatment operator reported that the sewage treatment plant was operating at capacity. Hikers complained about trail congestion. Beck claimed the event was not commercial, but after a search warrant, it was discovered that the gross income was nearly $50,000 with a profit of $9,500. Beck was charged, convicted, received a plea agreement, was fined, and was banned from the Canyon.

The National Park Service cracked down again on big group runs across the Canyon and started requiring permits.

Fastest Known Times and Crossing Records

As of 2018 the fastest known times for a double crossing is: 5:55:20 by Jim Walmsley in 2016 and 7:52:20 by Cat Bradley in 2017. For a single crossing, 2:39:38 by Tim Freriks in 2017 and 3:19:23 by Alicia Vargo in 2017.

The most known single crossings in a year was accomplished by 80-year old Laurent “Maverick” Gaudreau in 2006 with 106 crossings. Sadly in 2009, he murdered his wife and then took his own life at his home at Grand Canyon Village.

Double Crossings Today

As of 2018 a group permit is required for large groups to run below the Tonto Platform. No commercial groups are allowed. Any non-profit group like scouts needs a permit. Any informal group of 12+ also need a permit. . See: https://www.nps.gov/grca/learn/management/sup.htm#CP_JUMP_2602654

I have run more than 1,000 miles in the Canyon. You can find all my Grand Canyon adventure writeups here.

Sources

- Frederick H. Swanson, Dave Rust: a life in the canyons, 2007

- 1902 – Breaking a Trail Through Bright Angel Canyon

- 1925 – Building the Kaibab Trail

- 1928 – A Bridge Worthy

- The Record (National City, California), Jun 30, 1892

- Weekly Journal-Miner (Prescott, Arizona), May 19, 1897

- Los Angeles Times, Mar 12, 1898, May 17, 1903

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 1, 1900

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Jul 20, 1902, Jul 22, 1913

- Albuquerque Weekly Citizen (Arizona), Jan 24, 1903

- The Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, AZ), Aug 30, 1902, Jan 9, Aug 27, 1904, Nov 4, 1905, Aug 16, 1912, Jan 28, Apr 22, Aug 5, Oct 7, 1921, Feb 17, 1922

- Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City, UT), Aug 29, 1903.

- Arizona Republic, Dec 13, 1896, Feb 25, 1899, July 16, 1899, Aug 11, 18, 1903, Nov 10, 1905, Aug 1, 1911, May 27, 1928, Oct 21,28, 1974, Dec 15, 2007

- Albuquerque Journal, Dec 29, 1902, Oct 28, 1905

- El Paso Herald (Texas), Dec 29, 1903, Dec 29, 1921

- The Topeka Daily Herald, Dec 22, 1906

- The Cooper Era and Morenci Leader, Jul 8, 1910

- Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), Jul 16, 1913

- Panguitch Progress (Utah), Nov 19, 1915

- 1920 Rules and Regulations

- New York Herald, May 1, 1921

- The Chantute Daily Tribune (Kansas), Sep 21, 1921

- Essex County Herald (Vermont), June 16, 1921

- National Geographic Magazine, June 1921

- Williams News (Arizona), Feb 21, Jul 25, 1903, Jun 25, 1904, Oct 28, 1905, Feb 17, 1922

- The San Francisco Examiner, Feb 8, 1925

- The San Bernardino County Sun, Mar 4, 1928

- General Information Regarding Grand Canyon National Park, National Park Service, 1933

- Mike Campbell, “The Bright Angel Trail: Then and Now”, 2014

- Arizona Daily Sun, Jun 11, 2008, Feb 9 2009

- Nick Marshall, “Ultradistance Summary,” 1981, 1982

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Nov, Dec 1981, Feb 1983, Feb 1986, Dec 1987

- Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers, Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon

- KSL.com, Dec 19, 2006

- Fort Lauderdale News, Aug 11, 1985

- The Signal (Sant Clarita, CA), Jul 28, 2005

- Arizona Daily Star, June 10, 1960, June 18, 1961, Jun 21, 1964, May 19, 1979, May 4, 1990, Jun 28, 1992, Dec 6, 2007

- Grand Canyon History Facebook Group

- Arizona Man Busted For Organizing 300-Hiker Rim-to-Rim