Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:54 — 29.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

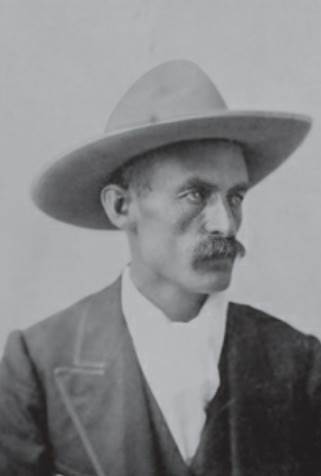

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

Endurance riding is the equestrian sport that includes controlled long-distance riding/racing. The sport has existed for more than a century in various forms. 100-mile trail ultramarathons, especially the Western States Endurance Run, Old Dominion 100, and Vermont 100 can trace their roots to endurance riding. Other trail 100s that emerged in the 1980s were also influenced by endurance riding practices.

Endurance riding is the equestrian sport that includes controlled long-distance riding/racing. The sport has existed for more than a century in various forms. 100-mile trail ultramarathons, especially the Western States Endurance Run, Old Dominion 100, and Vermont 100 can trace their roots to endurance riding. Other trail 100s that emerged in the 1980s were also influenced by endurance riding practices.

Ultrarunners should feel indebted to those of the endurance riding sport who had the vision to establish some early 100-mile trail races for runners. The trail 100-miler inherited many of the same procedures of aid stations, course markings, trail work, crews, medical checks, and of course the belt buckle award. Once ultrarunners understand their history, a common kinship is felt between the two sister endurance sports. So trade in your running shoes for horse shoes for a few minutes and learn about an inspiring and adventuresome endurance riding history that impacted the sport of ultrarunning.

The Origins of the Endurance Riding Sport in America

Usually the credit for establishing the endurance riding sport is given to Wendell Robie of Auburn, California when he initiated the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup) in 1955. (That history will be covered in Part 2). But endurance riding competitions of various formats existed long before 1955. Vermont must be recognized as the birthplace for the endurance rides in America.

Perhaps it depends on the definition for the “endurance ride.” The debate around the definition of what an endurance ride is, is similar to the definition of what an ultramarathon is. Is an ultramarathon anything over a marathon or do they start at 50 miles? One published definition for the endurance ride is “a timed test against the clock of an individual horse/rider team’s ability to traverse a marked, measured cross-county “trail” over natural terrain consisting of a distance of 50 to 100 miles in one day.” That is a modern, very limited definition especially the “trail” limitation, and the one-day limitation. But it still does apply to many very early endurance rides that predated the Western States Trail Ride.

Just as ultramarathons did not originate with the 1977 Western States Endurance Run, organized endurance riding did not originate with the 1955 Western States Trail Ride as Wikipedia erroneously states. Such a claim can also be found in other histories on the Internet. Some of the early endurance ride pioneers and events seem to have been forgotten or pushed aside.

Rides That Inspired Endurance Riding

In 1814, Sam Dale (1772-1841), the “Daniel Boone of Alabama” made a famous 670-mile ride on horseback in eight days from Georgia to New Orleans in the dead of winter to deliver a dispatches from Washington D.C. to General Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812. Some have called this the “greatest ride in United States history.”

Long before there was organized mail delivery, a French Canadian, Francis Aubry (1823-1852) was a American frontier legend who delivered mail from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Independence, Missouri during the war with Mexico during the 1840s. He purposely sought to break speed records and would on occasion ride his horses or mules to death.

In 1848 Aubry accepted a bet of $1,000 that he could make the 800-mile ride between Santa Fe and Independence in six days. He made arrangements to switch horses at various locations along the route about 100 miles apart. He ate as he rode, tied himself to the saddle, and took brief naps. An army Major stated, “He passed my train at a full gallop without asking a single question as to the danger of Indians ahead of him.”

After 100 miles he was going to switch out his yellow mare “Dolly,” but the relay station man had been killed and scalped and the horse were gone, so Dolly covered another 100 miles for a total of 200 miles in 26 hours. On September 17, 1848, Aubry arrived at Independence and men helped him out of his saddle and cut the ropes holding him on. The saddle was covered in blood. Aubry won the bet, arriving in five days, 15 hours. He ruined six horses along the way and several died.

These accomplishments would inspire horse riders for generations who wanted to prove that their horse breed was superior for endurance rides.

Early Endurance Ride Stunts

Before endurance ride competitions emerged, endurance ride “stunts” were performed to demonstrate what was possible riding horses for long distances. Such exhibitions have existed in both ultrarunning and endurance riding for more than a century. Here are a few examples of very early endurance riding stunts.

In 1903 a former officer in the Argentine Army performed a 210-mile ride in 14 hours at the Hippodrome (an outdoor stadium with a 1.5 mile track).

In 1907, a Captain Williams of the 7th Cavalry stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, after being on saddle for a 21-day march, boasted that after returning to the post, he could ride the 130 miles from Fort Riley to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in less than 48 hours. He set off the morning after on his 16-year-old saddle horse and covered the distance in 43 hours, with 28.5 hours actual riding time. He received many congratulations at the fort for his “plucky ride.”

The 1923 Pony Express Race

In 1923 a reenactment of the Pony Express ride was conducted as part of the 75th anniversary of the discovery of gold in California. On August 31, 1923 at 10:25 a.m. the 2,100-mile Pony Express “race” began. One lone rider started that morning when President Calvin Coolidge pressed a button from the White House. The fastest ride for the original Pony Express took 7 days, 17 hours in 1861. The riders hoped to break that record and many believed it couldn’t be done. It was estimated that 243 horses were used. At some point in Kansas, a cavalry relay team from Fort Riley accompanied the cowboy team and it developed into a race.

As the relay went through Utah, a seventeen-year-old cowgirl, Myrtle Gardner, rode a ten-mile leg that brought the mail pouch into Salt Lake City. The Governor and mayor were there to greet her at the post office. Thousands of others witnessed the arrival. A brief ceremony was held and a letter from the Governor of Utah to the Governor of California was inserted in the mail pouch. Then a new rider mounted a fresh horse and took off toward the west desert.

Will Tevis (1891-1979), a polo player and famed California horseman rode the last leg of the journey (with two relief riders), 278 miles from the California border at Lake Tahoe to San Francisco via Sacramento. Their leg took 13 hours, 58 minutes. Tevis finished up the leg, arriving at the finish at Tanforan on September 9th at 2:39 p.m.,, beating the cavalry team by only 21 minutes. In the last hours, the two teams had to race through some automobile traffic jams on the highway. Squads of police on motorcycles tried to guide the riders through the congestion.

The total journey took more than nine days. The newspapers inaccurately reported that the speed record was broken by 42 hours. More correctly the complete journey missed the record by about 42 hours. It appears that they may have been keeping track of actual riding time since the 1923 riders did stop for rests that would last for several hours. They stayed close to a planned schedule to let the public come out to watch them go by.

Also in 1923, Tevis, in San Francisco, using four polo ponies in relay, rode 200 miles over a measured track in 10 hours, 3 ¼ minutes to establish what probably was the fastest riding time in history for 200 miles. He became know as “The Iron Man of Age.”

Tevis and his rides would later inspire Wendell Robie’s 1955 ride on the Western States Trail and Robie’s endurance ride would eventually be named, “The Tevis Cup,” in his honor.

Transcontinental Rides

Both ultrarunners and endurance riders have had interests in crossing the continent on foot or on horse. In 1911, a woman, Nan J Aspinwall, accomplished a ride from San Francisco to New York. She was known as the “Montana Girl” and rode 3,200 miles across the country in 178 days. She was awarded the “Richard K. Fox” diamond medal, as the championship record rider of the world.

Aspinwall said, “I’ll never do it again and I advise no man or woman to undertake the trip. I have had enough of horseback riding to last me the rest of my days. I didn’t receive the best of receptions along the route and some of the days and nights I spent through parts of this country which I guess the Lord forgot, I don’t like to think about.” The journey took a toll on her. She greatly suffered through mosquitoes in New Jersey and toward the end was stricken by poison ivy which later developed into blood poisoning that put her down for three weeks.

In 1912, another woman, Alberta Claire, “The girl from Wyoming” went on a very long tour of the country on horseback. She started from her home in Sheridan, Wyoming, went to the Pacific coast and rode all the way down to the Mexican border.

She continued to Phoenix, Dallas, St. Louis, Cleveland, and ended at Atlantic City, New Jersey. For much of the way, her 100-pound part wolf dog accompanied her. She was received at many receptions along the way where she promoted woman’s suffrage. She claimed to have ridden one stretch of about 150 miles in 24 hours.

Claire said, “People ask me if I don’t get lonesome on my trips. Of course not. How can a person get lonesome when there are thousands of good books to read. I always carry a book with me in my saddle roll and at noons when my horse is resting or of nights, I sit and read my books.”

When Claire arrived at New York she commented that New Yorkers were skeptics. “No one will believe that a rattlesnake will not crawl over a hair lariat, and that when I am sleeping out in the hills or on the desert, I coil the lasso about me to keep them away. They ask me why a snake won’t cross a horsehair lariat. The only answer I know is, ‘Because it won’t and then the people laugh.” She said her primary reason for making the long ride was to help people along the way learn about Wyoming.

In 1912 four cowboys set out on horses to accomplish a 20,000 mile ride to visit every state capital in the lower 48 states. A horse-breeder association on the Pacific coast supported them with one dollar per mile. As of late 1913 they had visited 27 states and covered 9,000 miles. They averaged 20 miles per day and only one of the original starting horses remained, a little Arabian horse.

In 1914 a “Coast-to-Coast Endurance Race” involving 100 riders was planned for 1915 for a prize of $15,000. The race would start from Bangor, Maine. Riders would only be allowed to use one horse. The route would go to San Diego and finish in San Francisco, California. Stiff opposition arose and the race was never held.

On January 13th they arrived in St. Louis, Missouri. Leinhard said he was out to prove that Black Bess was the “best little mare that ever pranced to a bugle.” He had thus far averaged about 40 miles per day and his six-year-old black mare was on her fifth pair of horse shoes.

On March 21st, they arrived in Tucson, Arizona, where the local American Legion took good care of the horse at the University stables, where she was re-shod. Lienhard expressed some worry whether Black Bess would withstand the trip across the hot desert to California. The trip was taking more than a month longer than he planned and the desert was heating up. Five days later, as they approached Phoenix, sadly, Black Bess dropped dead in the Arizona heat. The loss hit Leinhard very hard. He traveled on to Yuma where he took a train back to Long Island.

Ride from Argentina to Washington D.C.

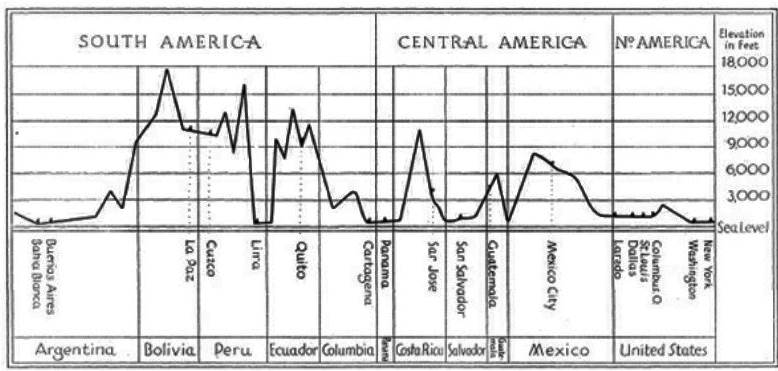

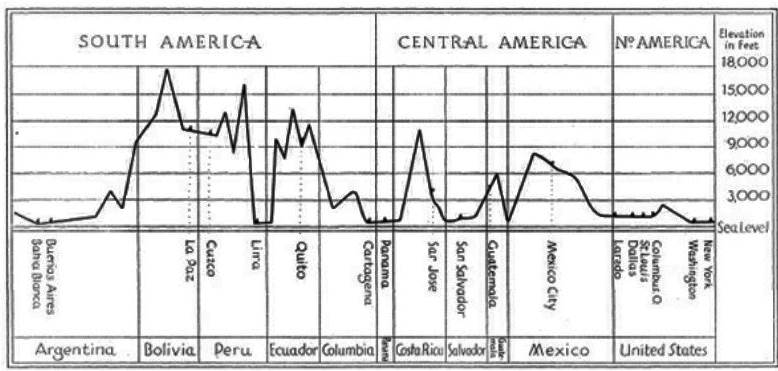

By September, 1926 he reached Ecuador. In June 1927 he reached San Salvador in Central America. It was reported that “he crossed the desert of Equator, rode through alligator-invested rivers, contracted swamp fever and dodged roving bandits. He crossed the snow-capped Andes three times, once going over the foothills of highest peak, El Condor, at an altitude of 17,400 feet. On several occasions his food supply ran out and he was forced to live on monkey meat. In Columbia he was had to make a raft for himself and his horse in order to get through the swamp lands. Because of a revolution in Nicaragua, he skipped that country using a ship.

His horse Mancha was the dominant horse, “When going through dense jungles where riding was impossible and where I had to go ahead on foot to cut interfering creepers, twigs, and branches with the bush-knife, Gato always had to follow behind Mancha who never allowed him to take first place.” He explained that his horses traveled best at a fast walk but for many miles in the desert country he traveled at a trot. The most miles he had covered in 24 hours was 96 miles.

After two and a half years, In February 1928, Tschiffely entered the United States at Laredo, Texas and was invited to stay at Fort McIntosh by the post commander. He said that he expected to write a book about his travels. (He did in 1933 and it was titled, Tschiffely’s Ride.”)

In July he arrived at Indianapolis and was referred to as the “Lindbergh on horseback.” He said, “I would not take anything in the world for my experiences, but I never in the world would make another trip like this.” Of the US he said, “Your country is beautiful, but so crowded. Everywhere there are tourists. I can’t seem to get used to so many people”

When he returned to Argentina, he decided to let his horses live out their lives on a vast ranch. He commented, “I have visions of many strange places we saw together, joys and sorrows, hardships an pleasures, and then the faces of many friends in far-away countries appear before me, friends is all station of life, friends without whose moral and other assistance we could never have succeeded. Good luck to them, and good luck to you, old pals, Manch and Gato.”

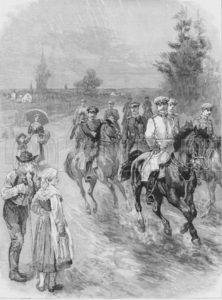

Theodore Roosevelt’s Endurance Riding Tests

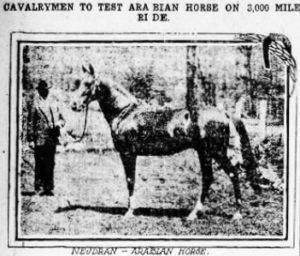

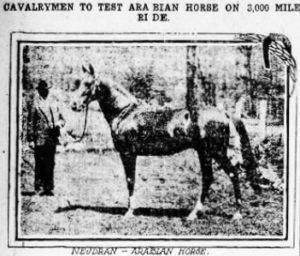

One of the most famous endurance rides was made by a Lieutenant Bassor of the Russian Army. He rode a single horse from Manchuria to St. Petersburg, a distance of 5,676 miles in eight months and three days. Knowing about that event, in March 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt received a letter stating that no real test had yet been conducted in America to demonstrate the power of the Arabian horse.

A test was proposed to for a 3,000 endurance ride across the country from Silverton, Oregon to Morris Plaines, New York, carrying regulation army equipment, ridden by a cavalry field soldier. The president endorsed the idea. Second Lieutenant E. Warner McCabe, a small, accomplished gymnast of the 4th Cavalry at Fort Riley, Kansas was selected. General Bell, the president’s chief of staff rationalized, “that the value to the government of such a test would be sufficient to warrant the undertaking.” The planned ride got national attention. But after several delays it was announced that the selected horse became ill and the ride was cancelled.

The tests were at first slow to happen, but by the end of 1907, they were occurring at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Motivation to pass these tests were further enhanced as a bill was proposed to move officers who failed the test, to work on improving rivers, harbors, and do other construction work. Some officers chose retirement instead of facing the endurance test. The Leavenworth Times reported, “Just now the army has begun to see the beginning of the weeding out process on the way in which the President is rather determined to get rid of many of the older officers now in the service.”

Some units were exempt from the riding test and instead were required to complete a 50-mile march in three days. This was the order that President John F. Kennedy discovered in 1963 that started the “50-mile craze” covered in another article and podcast episode.

Early Endurance Races

What about the races? Let’s go further back in time and read how they began.

On February 22, 1868, a 38-mile race was conducted between two famous horses, Empire State and Ivanhoe. The course route was from Brighton to Worcester, Massachusetts. Each horse pulled sleighs with 400 pounds (two men in each sleigh). The horses pulled the heavy sleds over many sections of bare ground. Empire State won the race in 2:33. The horse was given only a seven minute rest at mile 28. It refused to eat or drink and wanted to continue to run. Soon after finishing, Empire State became seriously sick and died at midnight. Ivanhoe didn’t finish, pulling out a few miles from the finish, but long after Empire State finished. But even trotting at a much slower pace, he died two months later from the effects of the match. Reaction was highly critical and even spread across the ocean to England. The outrage was huge in Boston and that year it sparked the creation of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA).

The Distanzreitt in 1892

In 1892 a brutal 360-mile race called “The Distanzreitt” was held between Berlin, Germany and Vienna, Austria. German and Austrian officers competed, each group leaving their capital cities toward each other and passing. A prize of 20,000 marks was promised to the winner and the event involved heavy wagering. About 250 horses started the race.

Only 145 riders and horses finished. About 25-50 horses died as a result from the race. Many more became lame, and one horse fell off a bridge. Morphine was used to keep horses going. The winner was Austrian, Wilhelm Starhemberg (1862-1928) who arrived at Berlin in 71.5 hours and only had spent eleven hours resting. His horse died a few hours later. In Vienna the German winner made it in 73.5 hours and his horse died the next day.

A London newspaper reported, “All the animals which have survived this race have suffered severely.” An Australian newspaper later commented, “It is only just to say that everyone who took part in the competition seems to be sorry and ashamed, not only for the cruelty inflicted, but also the disgrace incurred.”

The Great 1,000 Mile Cowboy Race

The race was covered nationwide in newspapers. Riders included famous colorful cowboys. John Berry, a railroad surveyor, won the race that ended at the entrance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show with a “tremendous crowd” of about 5,000 people in front. Berry’s eyes were swollen from lack of sleep. A reporter wrote, “Berry half tumbled from the saddle in front of Colonel Cody’s tent so weak and tired he was unable to rise to his feet or grasp the proffered hand of Colonel Cody. When able to speak, he asked Cody to ‘please take care of his horse.'”

Berry was asked if he was sore. “Sore? Well, I should say I was. I don’t feel much like sitting down, but I am so sleepy that I can’t talk. I have had no sleep for ten days to amount to anything. Some of the riders say I rode in a wagon. But they are liars.” He explained that he had started slow and was in last place because he walked his horse half the time for the first two days. “I did not catch the leaders until I reached Iowa Falls. From there we kept pretty close together.” He went into the lead as they entered Illinois and kept it to the finish.

Berry’s finish time was 13 days and 16 hours. He and his horse “Poison” covered the final 130 miles in 24 hours. Humane Society veterinarians examined Poison and pronounced that he was in fine shape. Buffalo Bill yelled, “Western range horses are the hardiest and best horses for the cavalry use on the face of the earth.” Other riders also finished that day.

The 1908 Endurance Race

Competitive point to point horse endurance races started to be conducted in the early 1900s. In 1908 an “international endurance horse race” was conducted from Evanston, Wyoming to Denver, Colorado, for a distance of nearly 500 miles. Originally the race was planned to start in Ogden, Utah for a distance of about 600 miles to Denver. Controversy arose as the president of the American Humane Society appealed to the governors of Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado to enforce established laws against such exhibitions which he said “are little better than the bull fights” put on in Mexico. The Utah governor agreed, stating that he was “opposed to the brutality manifested by owners of animals in tests of strength beyond reasonable bounds and that such should be prohibited.” The start was moved out of Utah to the Wyoming border city of Evanston.

Twenty-five riders and horses competed. The Wyoming Humane Society arranged to have veterinarians watch the race so there would be no cruelty to the horses. On the first day, Charles Workman, riding Teddy covered 43 miles during the first 4.5 hours. The dropout rate was huge. The winner reached Denver in six days and it was a very close finish. Frank Wykert on a bronco barely beat Workman on a Kentucky bred horse. They turned out to be the only finishers.

The Endurance Ride Sport Begins

The 1913 Vermont State Fair Endurance Ride

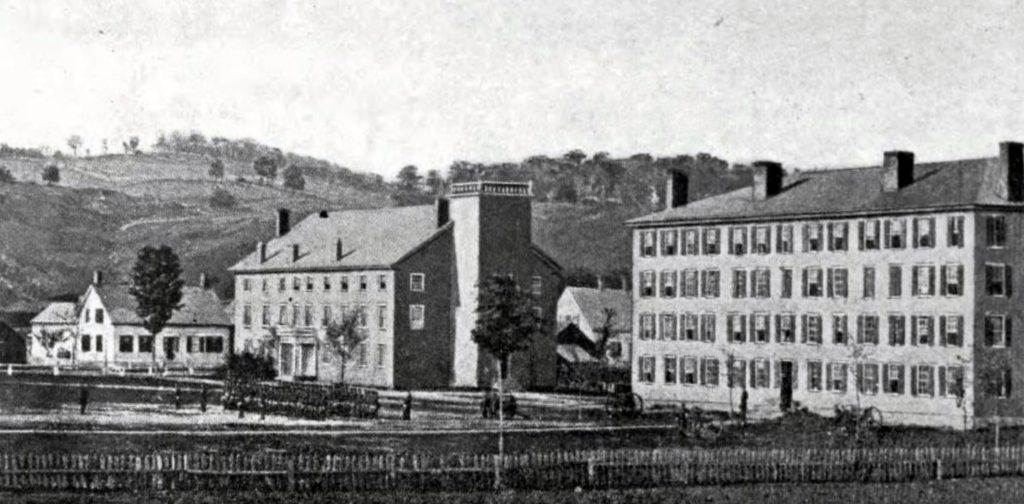

In 1910 an endurance test between a Vermont Morgan horse and a horse from the U.S. Army was proposed. The Morgan Horse Club made the challenge to the local army. General Leonard Wood (1860-1927) declined the challenge, stating that a test should involved multiple horses. Wood, who was a horseman from New Hampshire, countered with an idea to hold an endurance ride in 1911 with several horses. The competition would consist of 30-40 miles per day and could be conducted for several days, ending at the Vermont State fairgrounds at White River Junction, where the horses would be inspected. The event evidently didn’t take place in 1911, but Wood’s cavalry competition idea gave birth to the American endurance riding sport.

It was Captain Frank Tompkins (1868-1954) of the US 10th Cavalry who took the idea further, and implemented it. In 1913, he was the superintendent of military instruction at Norwich University in Vermont and had introduced Cavalry instruction back in 1909. He originated and planned a two-day 154-mile endurance ride to be associated with the Vermont State Fair, as General Wood had proposed three years earlier. When the event was initially discussed at a committee meeting of the Morgan Horse Club, there was some opposition, fearing that a race component to it could cause cruelty to the horses. Such concerns would be a constant factor in all endurance rides for more than a century. That is why such events were purposely called a “ride” instead of a “race,” even though most had a race component to it.

When Captain Tompkins mentioned the event at the university, he received enthusiastic support. The cavalry stable at the school would be used for the start of the ride and military students volunteered to work for the ride. As the ride was designed, features were considered to make sure concerns about cruelty were addressed. The course was laid out including stops for rest and feeding, with volunteers to care for the horses at each point. A veterinarian was selected who would accompany the riders. The format designed for this ride laid the foundation for endurance rides in the future, including the Western States Endurance Ride, which would be established more than 40 years later.

Before the 1913 event, Captain Tompkins was transferred, but Lieutenant Ralph M. Parker of the 11th Cavalry took over. Parker was famous for leading a company of 42 horses on a 20-hour, 127-mile ride without roads, in Cuba. He was enthusiastic about the planned ride which he would participate in.

Two days before the ride, the riders gathered in a classroom at Norwich University. They were given instructions and advise as to pace, times for stopping and feeding, and care of horses. Riders were told that “they would find muscles in their bodies they never knew they had before they had ridden the distance.”

The ride began on September 14, 1913. There were seven riders on small horses, Arabians or Morgans. The ride was open to all, Five cadets from the University competed along with Parker. An automobile drove ahead for the entire course to mark detours, place lanterns at night where the road was torn up, and gave other assistance. The eventual winning horse lost a shoe during the night at 2 a.m. The driver of the automobile went ahead to a town and retrieved a blacksmith who shod the mare by the light of the car. The rider had lost 55 minutes, but eventually caught up to the others. They all finished together in less than 31 hours and covered the last 17 miles in three hours.

The winning horse was a seven-year-old Arabian chestnut mare, Halcyon, who scored 93.3 points out of 100. She was a mare “of exceeding beauty and gentle as a kitten.” The winning rider was Howard H. Reid, a cadet at the University. He won $100. One observer of the event stated, “There can certainly be no two opinions about the fact that the entire test was a great success. It reflects in a most flattering manner on the cadets of Norwich University.”

The Vermont 300-mile rides

In 1918 the Army Horse Association conducted a race from Kansas City, Missouri to Omaha, Nebraska, a distance of 295 miles in six days. The horses had to carry 200 pounds and were required to rest ten hours each night. They were judged on their speed and condition after each day’s travel. The format for this race was noticed by the cavalry officers stationed in Vermont.

In 1919, an annual 300-mile rides began in Vermont which would attract many of the most prominent horsemen in the country. It became referred to as the Army Endurance Ride for the U.S. Mounted Service Cup.

Each rider and horse had to cover 60 miles per day for five consecutive days and carry a minimum of 225 pounds. The rider could never lead his horse on foot and had to care for his horse himself without the help of any handlers. The cutoff time for riding time was 55 hours to cover the 300 miles. Each day they had to cover the 60 miles in no more than 11 hours. For the health of the horse, the minimum time for each day was nine hours.

In 1920, many riders stayed away because they thought it was a military event. The cavalry officers were the finest riders in those early years, but the endurance ride was open to all and word eventually spread among the horse community. “Castor” again was entered in 1920 and 1921. He was much stronger and faster on a more difficult course and in 1921 finished in the money, in fourth place. “When he crossed the finish line the gritty little rascal was given a regular ovation.”

Here is a silent news reel of a 1921 300-mile ride in England.

The 1922 race included about 21 horses from across the country. It was hailed as the greatest endurance ride in the United States. The finish rate up to that time was about 50%. “They must travel rain or shine, and the course, which this year will extend through the hills of Vermont, beginning and ending at Burlington, is laid through all kinds of country, principally hilly.” Awards were huge with $600 going to the winner. Ten of the horses finished. The fastest overall riding time was 45 hours, 17 minutes, accomplished by Major Louis Beard on a seven-year-old thoroughbred mare named Vendetta. They placed first in both speed and condition at the finish.

In 1923 the endurance ride was held in Avon, New York and in 1924 was hosted in Warrenton, Virginia. Another 300-mile ride started to be held in Colorado Springs, where four horses were entered and all finished. The Eastern ride returned to Vermont in 1925 where it stayed for a few more years. The first woman to ride in a 300-mile event, did it in the 1928 contest in Colorado. That year was the last Eastern 300-mile event held in Vermont. 300-milers spread to California, South Dakota, and other places. The country’s fascination for endurance rides soon turned to bicycles and motorcycles.

The Green Mountain Trail Ride

As with the other endurance rides, they didn’t want to call this a race, but rather explain it as a test of the horse’s condition and stamina. The format evolved from the previous 300-mile rides. This new 100-mile ride required an average speed of about six miles per hour. Dr. Earle Johnson, the first president of the Green Mountain Horse Association, started these rides.

For the first year, 1936, the event was actually 80 miles in two days. The horses were not conditioned properly and the organization of the competition was a learning exercise. In 1937 the competition was extended to 100 miles in three days.

What was the typical training? “Any horse that is sound and of decent conformation between the ages of five and fifteen, and who has been worked regularly for a month or so previous to the ride should be able to give a good account of himself when ridden by an average rider. Conditioning can be accomplished by daily work of 10-12 miles. The rider will benefit from this as much as the horse.”

There were other very early 100-mile rides. In 1935 there was a 100-mile ride put on by the Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies. In 1938, in Illinois, 72 riders participated in a three-day 100-mile ride in the Cook Country forest preserves. A 100-mile ride with about 50 riders was held in 1939 near Des Moines, Iowa with the same three-day pattern at the Vermont Ride. Another ride was held in Oklahoma named the “Hoss Ride.” Great Falls Montana got into the game in 1941 with its three-day Montana 100-mile ride “to stimulate interest in horseback riding on trails and cross-country in Montana.”

By the mid-1950s Endurance Rides started to become more popular. They were held in Vermont, Tennessee, California, and Nevada. The most publicized race was the Florida 100 with as many as 70 riders going 100 miles. The stage was set for the birth of the Western States Trail Ride.

Continued in Part 2 (1955-1970)