Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:52 — 24.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

There is a special breed of ultrarunner that historian Jim Shapiro in 1980 called the “solo artist.” These runners usually had solid ultrarunning abilities, but instead of regularly completing in races, they used their abilities to accomplish stunts. This was done to garner attention from spectators and fans and to gain income and sponsorships. Solo artists would always invent and claim “world records.” They had creative nicknames and their marketing people would prop them up as being the “world’s greatest runner.” Solo artists have always existed in ultrarunning and still exist today.

There is a special breed of ultrarunner that historian Jim Shapiro in 1980 called the “solo artist.” These runners usually had solid ultrarunning abilities, but instead of regularly completing in races, they used their abilities to accomplish stunts. This was done to garner attention from spectators and fans and to gain income and sponsorships. Solo artists would always invent and claim “world records.” They had creative nicknames and their marketing people would prop them up as being the “world’s greatest runner.” Solo artists have always existed in ultrarunning and still exist today.

In the 1920s and 1930s as professional running races were drying up, many of the ultrarunners of that time used their creativity to become a solo artist. They did various stunts and accomplished numerous point-to-point “journey runs” to claim “world records” or what today we call a “fastest known times” for a runs between cities. Some of the solo artists fabricated their accomplishments to bolster their running resume. Reporters at the time just believed and published what the runner or their manager would say about them without any verification. Fabrication of accomplishments even happens today.

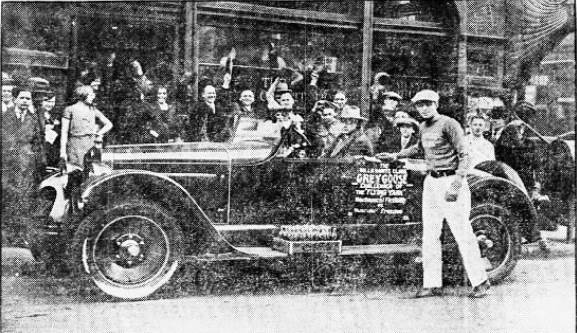

Many of these solo artists were fascinating charismatic characters who had impressive running abilities and accomplished many outlandish stunts. One of these amazing characters was “The Flying Yank,” John J. Seiler (1903-1983) of Brooklyn, New York. He would leave a lasting impression on tens of thousands of fans and young high school students by putting on entertaining running stunts, organizing city hikes, and giving interesting lectures on fitness and health.

Young Runner Emerges

John Seiler said that as early as sixteen years old, he started to do long journey walks. He came out of nowhere and said he was a “champion pedestrian.” He claimed that in 1919 at the age of 16 he had walked from New York to Los Angeles, 3,500 miles on the Lincoln Highway, in three months, twenty days, beating Edward Payson Weston’s mark by 13 days. He also claimed that he had walked from Boston to Jacksonville, Florida in 24 days, slicing seven days off the “record.” He said he had run from New York to Philadelphia, a distance of 106 miles in 24 hours.

Were all these accomplishment true at such a young age? We will never know for sure. In 1921 at the age of 18 he claimed to have walked from Brooklyn, New York to Houston, Texas, taking a round-about route for a distance of about 2,500 miles. Newspapers found him in various cities along the way. By stitching those stories together, he traveled at a believable rate of about 28 miles per day. But in later years he claimed that he covered the entire distance in only 44 days which was an impossibility at that pace. This was the first clue that perhaps some of Seiler’s claims were grossly exaggerated.

The Flying Yank of Tampa, Florida

Young Seiler boastfully, put out a “challenge to the world” to compete in any heel-to-toe exhibition. It didn’t matter if anyone responded to this challenge, just issuing it gave him attention. He wanted to be signed by a baseball club to have him do backward walking exhibitions during pre-game. The opportunities didn’t come as often as he hoped, and he returned to New York for the summer of 1922.

Seiler claimed that he attended Tulane University in New Orleans but never said when. He said while attending there, he won pentathlon and decathlon championships. When did he attend Tulane? It is possible that he did for a couple years during 1923-24, because his name did not appear in the newspapers for those years.

But, by 1925 Seiler was gaining fame again. He was started to also be called, “the human locomotive.” His “recorda” and stunt claims at that time included:

- walking from New York to San Francisco in three months and 20 days.

- walking from New York to Houston, Texas, in 44 days and two hours.

- walking from Boston to Jacksonville in 24 days and three hours.

- walking 1/3rd mile in 1:36 using heel and toe style.

- walking a mile in 6:25.

- running from New York City to Philadelphia (106 miles) in 24 hours

- walking seven miles in 49:42, in Indianapolis

- walking a half-mile in 2:56, in McAlester, Oklahoma

Gaining Fame

On April 26, 1925 Seiler accomplished his lifetime greatest running achievement that was witnessed by many. It occurred at one of his only true races. He raced in a field of 46 runners for 10 miles at Cermak Park in Chicago that included some accomplished runners. He won with a time of 51:00 that he claimed for the rest of his career to be a world’s record. It wasn’t. The world best at that time was held by Alfred Shrubb of Great Britain with 50:40. But if Seiler indeed ran that fast for ten miles, it was an American best at that time.

After that, Seiler became very publicly brash, which was typical for the professional runner at that time. He challenged “any man in the world for a race of a marathon nature”. He boasted that he could lower any amateur long-distance mark. He said he lowered records every time that he had tried.

The Flying Yank became successful in getting hired to do various exhibitions. In Illinois and Wisconsin, he entertained baseball fans at a minor league game. He raced against players on the teams around the bases. The player would run a complete circuit abound the bases while Seiler would run backwards from second base to third, and then to home plate.

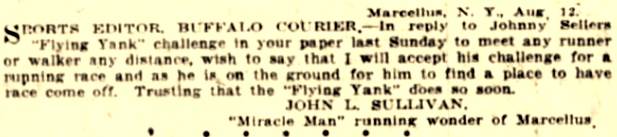

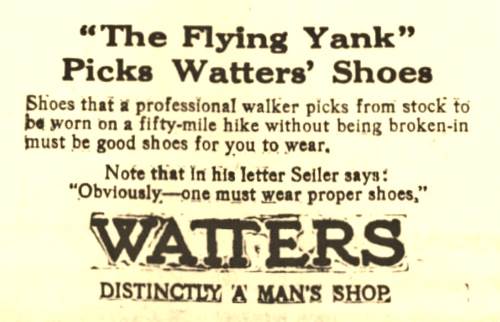

Racing Against an Automobile in Buffalo

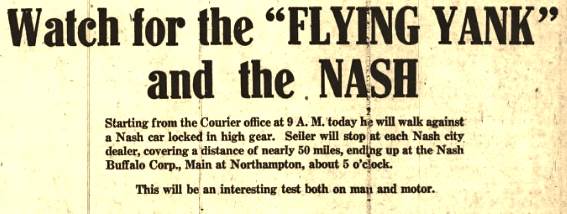

In August, 1925 Seiler took his show to Buffalo, New York, to put on a series of three-day stunts that began a pattern of events that he would replicate in other cities. This Buffalo event was sponsored by the local Nash automobile dealers and by The Buffalo Courier Newspaper. The city was curious about this young man who had so many fascinating running accomplishments to his name. How did he do it? The 23-year-old Seiler gave credit to his diet. He used a meat-free training diet and said, “For the last few days I have lived entirely on rye bread, vegetables, buttermilk, raw eggs and plenty of water. I maintain that a man or boy never can drink too much water, and I drink water at every opportunity.”

On the second day Seiler hosted a ten-mile city hike for various clubs where he would demonstrate various styles of walking along the way. Nash cars drove with the hikers to pick up any stragglers. About 350 hikers came out to participate. To liven things up, he organized running and walking relay races and raced the winner of each event, defeating them all. He also raced against a marathon runner from the University of Buffalo in a two-mile race and won. The Flying Yank showman won over Buffalo.

The main event was on the third day. Seiler raced against a Nash automobile locked in high gear through the city’s most congested traffic for 25 miles. It was called, “The Traffic Obstacle Race.” The car had to obey all traffic regulations while Seiler could keep running.

Seiler took the early lead for a few blocks but soon the Nash caught up as he was delayed by traffic lights. In the end, the car beat the Flying Yank by an hour. The asphalt heat had been so hot that Seiler’s feet became badly blistered halfway into the race.

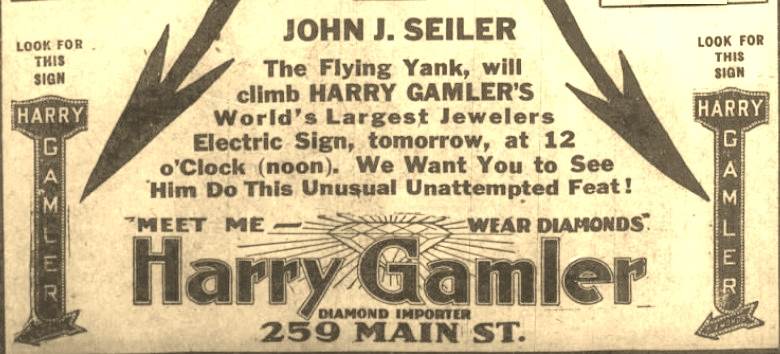

After the race, Seiler told a reporter that “every athlete should drink beer as a stimulant and declared that most of them do. The malt and hops contained in beer are excellent body builders he stated.” To close out his 1925 visit to Buffalo, thousands gathered at a jewelry store to witness “at the risk of his life” his climb to the top of a towering sign to wave farewell to his Buffalo admirers.

Racing Against an Automobile in Atlanta

The automobile never exceeded eight miles per hour and was locked in high gear. The man behind the wheel who drove the motor shared high praise about Seiler, who he observed during the entire run. He declared that Seiler showed marvelous determination and that sometimes the car was slowed down to about a mile an hour to allow Seiler a moment to jog and rest. Seiler even ate lunch as he kept one hand on the steering wheel moving the car around in a circle. Crowds cheered him on.

It was claimed that he covered 50.3 miles in 7:20. Seiler proclaimed to the newspapers that his 50-mile performance was a world record. But it was actually was nearly two hours slower than the 50-mile world best at that time. He would usually proclaim world records after he ran. This was a very good strategy to bring out more spectators to his other events.

Later in the week, Seiler raced head to head against a Wills Sainte Claire automobile for 78.2 miles from Athens, Georgia to Atlanta. Seiler said, “I feel that I am in as good condition for this contest as I have been in former events and believe I can beat the machine.” The car was not allowed to go faster than six miles per hours.

Two miles into the race the car went ahead. The news report included, “It began to rain and never entirely quit until the contestants came in. Although the runner was drenched during most of the race, he kept doggedly at this task and several times passed the car, which was locked into high gear.” Along the way, Seiler was almost hit by an unidentified motorist and injured his knee dodging out of the way. He continued on, paced by some local college track stars, and finished in 16:03, six minutes behind the car.

During all his Atlanta races, Seiler always drank Coke. Yes, it was great for running ultradistances, but he probably also did it to gain a sponsorship. It was reported that “he declared that contrary to the belief of many athletic and track coaches, he had found that Coca-Cola had ingredients that were just what he needs to bolster his strength and to give him the punch to carry on in the final stretches of his competitions.” The Coke sponsorship came and he was the only athlete in the country that was sponsored by Coca Cola.

“Doctor” Seiler

In 1926 the newspapers suddenly started to refer to the Flying Yank as Dr. Seiler. He claimed to have a PhD as a physical culturist and started to practice natural methods in Miami. Tulane University was mentioned, but it is highly unlikely he received a doctorate degree there. Articles at first only mentioned that he was once a student there, but soon he said he was a graduate from Tulane’s medical school. Most revealing is, at that time his published age took a huge jump from 23 years old to 29 years old, helping his claim that he was a doctor.

In the 1920s bogus degree-mills were very numerous, causing Senate hearings to be held. During the early 1920s, despite the numerous articles about Seiler’s walks and runs, he was never mentioned being in New Orleans where Tulane is located. In 1926 Seiler moved to Chapel Point-on-Potomac, Maryland where he had a “physical culture school” and a “health farm.” It appears that Seiler granted himself a degree that matched his “physical culture” beliefs, a fitness movement that originated many years earlier.

The newspapers gushed over the Flying Yank. He was described as “a tall young man, with the color of perfect health. Dr. Seiler appears too slender for strength. But so firm are his muscles, so finely drawn are the sinews in every inch of his long, lean body, that he weighs 176 pounds, for all his slenderness. His strength is the agile, deceptive strength of the greyhound and from head to foot he is a bunch of steel fibers.” He and his manager would bring to each city a large collection of trophies that he had been awarded from other cities as proof “that they were officially presented for long distance runs.”

For the previous three years, Seiler said that he made 100+ mile runs on average once per month. He also claimed to hold 37 “world records.” New claims emerged included running 25 miles in 2:15:17 and running from Washington D.C. to Richmond, Virginia (137 miles) in 28:57. He also ran from Macon to Atlanta, Georgia (104 miles) in 17:03.

With all the attention, a national columnist, Damon Runyon, who had his doubts of all the claims by solo artist runners, proposed that the Flying Yank race coast-to-coast against the “Human Dynamo,” H. Levitt, from California who planned on doing a trans-continental run. Runyon proposed, tongue-in-cheek, that Levitt start from Los Angeles and Seiler start from New York. Runyon wrote, “I do not know that a Coast-to-Coast foot race would be of any great value to science, but it would at least attempt to settle an argument of the world’s long distance running champion.”

Running 100 miles between cities

Seiler moved his running show to the southern states and started a pattern of running 100+ miles when he visited a region of the country. He first ran 114 miles from Jacksonville to Daytona in 19:40 “without a stop.” He then ran from Orlando to Tampa, Florida, about 105 miles, in 15:20. The mileage was likely closer to 90 miles.

While in Miami, he raced 440 yards against a greyhound dog named “Red Juggler” and won although the dog had to run 330 yards. During the last lap of the race Seiler dislocated a bone in his foot, causing his foot to swell terribly.

Trans-Continental Run

On September 10, 1927 Seiler started a trans-continental run from Atlantic City, New Jersey to Pasadena, California. His goal was to do it 70 days. Along the way, he mentioned in one religious city that he did no running on Sundays. Somehow with all this running and even skipping Sundays, he managed to also lecture in many schools along the way. He claimed to average running 50 miles per day and said “it isn’t so much the speed, as the grind.”

Seiler finished his trans-continental run in 56 days. He said he wore out seven pair of shoes and lost 14 pounds. He claimed that he ran only about nine hours per day and skipped Sundays. The published distance was 3,052 miles. All the numbers did not come close to adding up. But no one noticed.

Challenging the Bunion Derby

In 1928, C. C. Pyle organized his famed race across America, Los Angeles to New York, coined by the press as the “Bunion Derby.” Many of the truly best ultrarunners in the world participated. These included many who competed in legitimate races, something that the “Flying Yank” didn’t do. Some of them were also talented “solo artists.” Seiler didn’t enter the race, instead mocked it, and announced that he would start running the same route one week after the start of Pyle’s race that began on March 4, 1928. He said, “I am real confident that I will be able to set a mark of 50 days actual running time.” Pyle simply ignored Seiler.

Seiler was sponsored by Herbert Lubin (1886-1943), a millionaire sportsman and motion picture magnate, and was a friend of the Flying Yank. Lubin built the famed Roxy Theatre in New York City. When Seiler had belittled the Pyle “Bunion Berbyissts,” in the press, his friend Lubin offered to pay all expenses for a proposed catch-up run. It was rumored that a $25,000 wager was also at stake. Lubin’s brother, Barney, was put in charge of Seiler’s crew. Some newspaper men also traveled along to verify the run and time.

Seiler started his run strong, running 45.5 miles the first day in 11:11, matching the distance that the Pyle runners ran over their first two days. On the next day, at Rialto, California, after running only 14.5 more miles, the Flying Yank quit. He blamed his failure on poor conditioning. Barney Lubin, his crew chief, was disgusted with the effort and commented, “I’m not a runner, but I could do better myself.” Perhaps the Flying Yank was starting to cause some doubt about all his claims.

Back to Running 100 Miles

Seiler laid low during the rest of the 1928 Bunion Derby but emerged back in the press with a 100-mile run on December 15-16 from Decatur to Peoria, Illinois. Paced by Peoria High School and college runners he finished in an impressive 16:22. The distance was probably closer to 85 miles although witnesses rode along in a truck and likely checked the odometer. Odometers at that time were very untrustworthy as car dealers wanted to show high gas mileage.

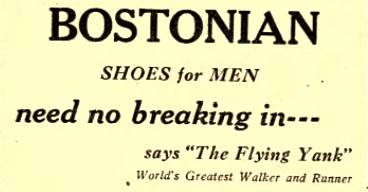

Seiler claimed his run had set a 100-mile “world professional record.” The best world mark was actually about three hours faster at that time. A newspaper claimed that he held more than 100 professional long-distance running and walking records. The true number was probably closer to zero. While in Illinois, “Doctor” Seiler also did a series of heath talks about his “platform on physical culture.” He always traveled with his manager, Pascal Juliano, who handled his appearances, sponsorships, and public relations.

Arrested in Illinois

In February 1929 both Seiler and his manager Juliano were arrested in Quincy Illinois, accused of stealing $4,500 worth of diamonds. When their vacated room was searched, a white gold ring had been found in the room without the setting which had been sawed out. Seiler and Juliano had also matched the descriptions of witnesses who saw two men throw a brick through the jewelry store window. An arrest warrant was issued. The two firmly denied being involved in the robbery.

As news was released about their arrest, some local businesses became nervous that they had been scammed by Seiler and Juliano. It was charged that the two conducted a scheme approaching companies posing as “health experts” and representatives of the state department of public health. They sought money from these companies in exchange for promoting their products in Seiler’s health lectures. The two quickly returned $150 obtained from Quincy stores for advertising.

The robbery evidence weakened. The eye witnesses could not identify the two as being the suspects. Authorities shifted to work on a case that the two were working a “confidence game,” passing themselves off as members of the state board of health. The two brought in bags of newspaper clippings about their activities in other cities which they probably used to convince other clients to sign up with them. The local newspaper cast some doubt that Seiler was actually a doctor.

The only incriminating evidence found against the two during this period of prohibition “was a pint bottle of gin and another pint bottle partly filled with either cheap whisky or hootch.” All charges were eventually dropped. The two soon moved away from Illinois and went to Ohio.

Traveling on the Lecture Circuit

In late 1930 as the Great Depression was raging, Seiler, now age 27, ran 100 miles again. This time it was in Tennessee. He ran from Jasper to Nashville which likely was more than 100 miles. He ran accompanied by several official cars, friends, and two food trucks that supplied his needs. He arrived in Nashville with a motorcycle police escort and finished in 19:19, cheered by a large crowd. He had been publishing a series of dieting and physical culture articles in the local newspaper so was well-known.

In 1932, Seiler continued his 100-mile runs, doing them in Ohio and Indiana. Later in the year he went to Michigan and ran 100 miles from Cadillac to Grand Rapids in 16:45. Afterwards it was discovered that he tore a ligament in his right knee. He evidently healed, because in 1933 his 100-mile show and lectures appeared in El Paso, Oklahoma City, and Phoenix.

Seiler’s lectures gave some sound advice such as: “Walking in my opinion is the only exercise good for one and all. Walking is the best aid to good health. It is a natural exercise and given to us by Mother Nature as such. Why should we pass up Mother Nature’s perfect exercise for others?”

By 1935 Seiler added to his life history that he served in World War I in France, returning in 1918. But he would have only been 15 years old when he returned. No military records were found to prove his claim. He said, “I was in poor health at the time and decided to walk and run to better my health. After a short length of time, I was so imbued with the wonders of exercise I made it my business to help and advise others.” Seiler also claimed to drink at least 10 glasses of milk daily and sometimes drank twice that much. He was sponsored by a dairy.

In 1937, at the age of 34, Seiler was being referred to as the “former” Flying Yank and was still lecturing at schools. He even claimed to have traveled to lecture in Europe. In 1938 at the age of 34, he claimed to hold 57 world records and said he was 42 years old. He gained yet another two years in age! Apparently fibbing about his age helped his business, impressing people with how young and healthy he looked for a man of 42. In 1939 he was still visiting schools in Pennsylvania and also conducted running backwards stunts at sporting events.

Retirement

Who really was John J. Seiler? I conclude that he was a very talented ultrarunner who conceived of a way at a very young age to gain fame and money through self-promotion. But most of his “record” accomplishments were likely fictional. I believe his trans-continental runs and many other journey walks and runs were fabricated by taking rides or altering the time they took. He did run some very fast legitimate 100-mile runs. He was able to smartly gain sponsors by promoting local products during his various lectures to schools and clubs in exchange for money from the local businesses. With his creative stunts and using a very savvy manager, he became very famous and successful. His bogus doctor degree gave legitimacy to his training theories and lectures. He never had problems getting signed up for lectures. He conducted a rather brilliant scheme or business to use his athletic talents for fame and gain.

Sources

- The Columbia Evening Missourian, Apr 8, 1921

- The Tampa Tribune, Nov 11-17, 1921, Mar 14-28, 1926

- Healdsburg Tribune, Dec 15, 1927

- Geoff Williams, C. Pyle’s Amazing Foot Race: The True Story of the 1928 Coast-to-Coast Run

- New York Tribune, Apr 8, 1922

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), Nov 2, 1922

- The Journal Times (Racine, WI), Jun 2, 1925

- Buffalo Courier, Aug 13-18, 1925

- Buffalo Times, Aug 20, 1925

- The Atlanta Constitution, Dec 8-20, 1925

- Miami News, Dec 19, 1926

- The Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb 24, 1926

- Monroe News-Star (Louisiana) Mar 28, 1927

- The Orlando Sentinel, Jan 23, 1927

- The Miami News, Jan 30, 1927

- Albuquerque Journal, Oct 23, 1927

- Emery County Progress (Castle Dale, UT), Nov 26, 1927

- Santa Ana Register, Mar 12, 1928

- Lincoln Journal Star (Nebraska), Mar 13, 1928

- Arizona Republic, Mar 11, 1928

- Decatur Herald, Dec 16, 1928, Feb 22-23, 1929

- Dayton Herald, Sep 24, 1929

- Battle Creek Enquirer, Sep 25, 1932

- El Paso Times, Nov 22, 1935

- The Tennessean, May 10, 1938

- The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania), Jan 31, 1939

- Chetopa Clipper (Kansas), Apr 20, 1921

- Ancestry.com