Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:55 — 32.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Both a podcast episode and a full article

Today, few know of the name of Johnny Salo of Passaic, New Jersey. His story needs to be told. In telling his story, I will also tell the story of the very famous races across America that were nicknamed the “Bunion Derbies.” Several fine books have been written about this famed race held for two years, that attracted the greatest ultrarunners in the world. I won’t try to duplicate all the details of those races but will tell that story from the perspective of its greatest ultra-distance runner, Johnny Salo. The primary source used are the daily updates published in Salo’s hometown newspaper. The is the first of two articles about Salo and the Bunion Derbies.

Immigrant living in New York City

John “Johnny” Salo was born May 25, 1893 in Wiborg, Finland. His original Finnish name was Johannes Nakka. Johnny became a sailor during his teen years. He first visited America in 1908 at the age of 15, loved the country and felt the desire to someday live there, and leave his homeland that at that time was under Russian control

Running was a part of the lives of many Finns. At the age of 16, Salo was said to be Finland’s top amateur cross-country runner. In 1911 at the age of 18, he immigrated to the United States to Gulfport, Mississippi, through Antwerp, Belgium. He came over on the ship ”Cis” as a member of the crew of that ship. In 1914, living in New York City, he started to apply for United States citizenship but it wasn’t granted at that time. He worked for the United States Shipping Board, working himself up to the first officer.

As World War I broke out he enlisted into the service along with about 500,000 other immigrants with the hope of receiving citizenship later. Johnny joined the Merchant Marines and served a three-year tour of duty on an emergency fleet based out of Staten Island, New York. He worked his way up through the ranks and achieved the officer rank of Ensign. During the war, he made ten trips on convoys across the dangerous waters of the Atlantic, that were infested by submarines.

In 1917, at Brooklyn, he was injured in a scary trolley crash. The car carrying about 50 people was being pulled up a hill on 39th street in Brooklyn when the coupling broke and it slid down the grade. The motorman tried fruitlessly to reverse power and then leaped into the street. The trolley car crashed into a car with passengers. Salo along with 19 others were injured and treated. Salo had other poor luck living in the city. One day he was assaulted as he was coming up the stairs out of a subway. “The assailant inflicted lacerations and contusions on Salo’s head and face.”

In 1917, Salo married Amelia Hoveland (1894-1956), his boyhood sweetheart also from Finland. They soon had a son Leo John Salo (1918-1970) and a daughter Helen (1920-1992).

World War I ended in 1918 but Salo continued to work on ships. In August 1919, Salo was on an American steamer, Englewood, with 47 seamen bound for Rotterdam. As it was near the North Sea on the Thames River, it struck a mine. They radioed for help and tugs came in time for the rescue and the ship did not sink.

In 1922 Salo was finally granted U.S. citizenship. He was among 192,000 immigrant war veterans who eventually were made citizens after their service in World War I. About 1924, the Salo family moved to Passaic, New Jersey where he had relatives living.

Begins competing in running

All his life, Johnny wanted to be a great runner like other illustrious Finns of the time such as Paavo Nurmi (1897-1973) who held world records and won medals at the Olympics. Even though Salo spent so much of his life on ships, he trained on the decks, frequently doing 12-mile runs. “He sprinted around the deck until he was dizzy from running in a circle. His shipmates kidded him good-naturedly, but he didn’t mind. He kept in condition.” Salo said, “I would start running about four or five miles a day and gradually increase the distance until one day I ran forty miles. From this showing, I decided to participate in track games.””

In 1925, Salo started to compete in long distance events shorter than a marathon. He said, “In the first few races, I gave poor exhibitions. This did not discourage me. I kept plugging along until I improved.” In May he raced in a 12.5-mile race with 400 runners on the hottest day of the year in New York City. He finished in the top five of his Finish-American running club, helping win the team gold. “As a member of the team he received a beautiful gold medal and then secured another gold medal for being the first New Jersey novice to cross the tape. Much more will be heard from Mr. Salo in the future as he is making an effort to become one of the leading marathoners of the country, and it would not be surprising to see him listed among the leaders in future races.”

Salo started to run marathons in about 1926 and did very well. He finished 7th in the Passaic City Marathon, 7th at Port Chester, and finished 13th at the 1927 Boston Marathon. In May 1927, he placed 15th in New York to Long Beach Marathon with 3:10:53,

As a member of the the Finnish-American Athletic Club, he gained some national attention when he placed 3rd at Valley Forge-Philadelphia Sesquicentennial race. He then joined the Millrose Athletic Association of New York City,

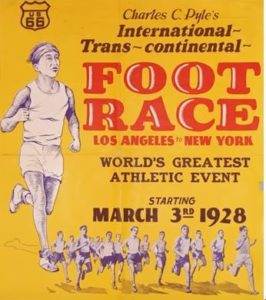

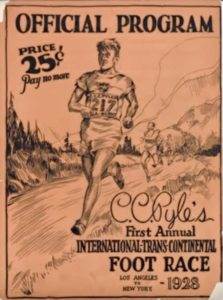

The 1928 C.C. Pyle Bunion Derby

Pyle said his race would be “The greatest sporting event in history.” Many were critical of the race and a doctor predicted that “five to ten years would be shaved off the runners’ lives.” Another man hearing that runners would be checked out by doctors before the race commented, “Well, if a man enters a 3,000-mile foot race, the first thing to examine is his head.”

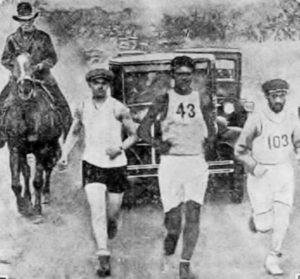

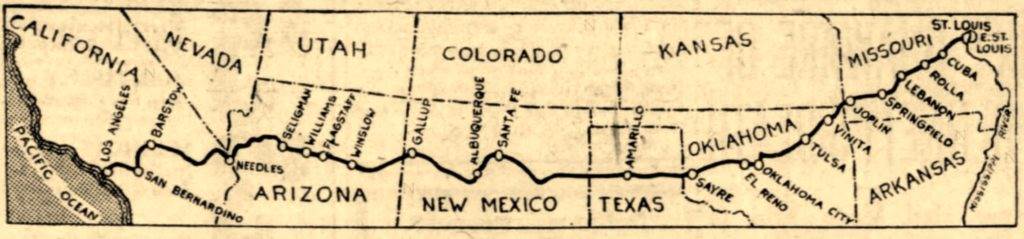

The race would generally follow what became known as route 66, which was still largely unpaved, so it mostly was a trail run. The exact course and daily “control points” would be made up as the race was underway in order for Pyle to find the towns that would pay him to stop there and allow him to put on his evening side-shows.

Salo enters the 1928 race

Salo’s talent as a runner was unknown even in his New Jersey hometown. But, the famed Finnish trainer, Hugo Quist (1890-1941) recognized his running talent and managed to get Salo an invite to the race. (Quist had trained legendary Finnish olympian gold medal runner Paavo Nurmi, and in later years would train world champion skater Sonya Henie (1912-1969)).

Salo was determined to run in the historic race, believed he would win, and trained hard for a month. He ran an hour and a half each day on steel decks of a shipping steamer. “Being a merchant marine, Salo trained on nothing else but beef stew and Yankee Hash.” He was described as being “solid bone and muscle,” at about 160 pounds. He attempted to raise funds from some local Passaic citizens but did not have much success, having only lived there a few years. One man offered to give him $300 if Salo signed a contract to let him be his manager and guarantee him half of his winnings. Salo declined that offer. Instead, he depleted all his savings, cashed in his insurance, found every cent possible, and his wife went to work. He was betting everything on winning and did obtain enough money to pay the required $150 entrance fee and buy six pair of shoes for $96.

Arthur G. McMahon of the Passaic Daily News wrote, “There were no bands and handshakes as Salo departed from Passaic except for his family and a few Y.M.C.A track men. Few knew he was going. And if he comes through it won’t be due to any demonstration by citizens, but in Johnny Salo, who believed in himself.” Salo and the other runners camped out near the start for days getting training and waiting for the race to begin. Pyle charged the runners to sleep in tents and to eat meals.

The start

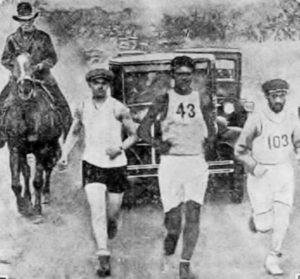

On March 4, 1928, 199 runners gathered on a muddy track, and Pyle organized everyone in rows of 20, separating the men, as much as possible, into groups by nationality. There were 24 countries represented, and many athletes were adorned in colorful uniforms and carried flags representing their respective nations.

At 3:04 p.m., Red Grange, “the galloping ghost” of football fame, lit what reporters described as a “starter bomb.” It exploded with a deafening bang, and the spectators in the stands began cheering and shouting.

After each stage, during the evenings the race staff provided a carnival for each town they stopped in, but the runners and the others spent their time eating and sleeping unless they were asked to appear. Nearly all of them stayed in bed until it was time for breakfast.

Johnny who?

It took two weeks for Salo’s hometown newspaper to notice that he was in the race and doing well, placing high in the stages in Arizona. Not knowing who he was, the Passaic, New Jersey newspaper first referred to him as a “youngster” and a “lad” but he was 34 years old. One columnist wrote, “I for one did not know this youngster was in this race. Let someone who has the time, keep in touch with John Salo, find out his condition and whether or not he is in need, and then let’s do something to keep him in the race. I for one would like to know just who he is, where his home is, and anything else that anybody may know about him, for he is a credit to Passaic and showed great pluck in starting such a long, grueling race even if he doesn’t finish.”

Arizona

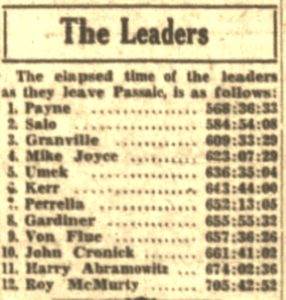

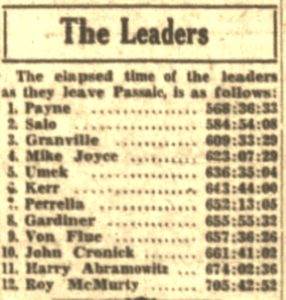

By day 16 near Winslow Arizona, Salo climbed into 6th place but more than 20 hours behind the leader, Newton, as they were nearing Winslow, Arizona. Harold Burpo (1892-1967), the brother of the former local Passaic sheriff, was crewing for Salo but his support was minimal.

Back home, his 12-year-old son Leo, 7-year-old daughter, Helen, and their mother were “praying that ‘daddy’ will not fail to finish well up in the race. The home is a gathering place all day and late in the evening for neighbors awaiting news.”

Salo wrote to his hometown Legion members and let them know that he had already worn out four pair of shoes. If he couldn’t find more funds he would soon be forced to drop out of the race. He also mentioned that he had no trainer along to give daily rubdowns. “The other runners had trainers and were receiving all kinds of attention.”

By Day 18 Salo’s local American Legion stepped up to the plate to try to help, establishing a funding campaign. Within a day, donations started to come in and word was quickly sent to Salo to “keep plugging” that help was on the way.

By Holbrook, Arizona. Fellow Finish-American, Arne Souminen (1900-1972), had taken the overall lead. Newton had dropped out due to injury and Payne was suffering from tonsillitis, in 2nd place. Salo was in 6th, about ten hours behind.

New Mexico

Salo reached Albuquerque, New Mexico with only four cents in his pocket. While other runners were getting great treatment, he had no dry clothes when he finished after a rainy day and received no rubdowns.

Texas

The runners entered Texas on day 35. They had run more than 1,100 miles. Salo placed a strong second in a 37-mile leg to Amarillo, Texas in snow and rain. He was 17.5 hours behind the leader, Suominen. The next day he again finished second and climbed into 4th place overall.

Back home in New Jersey the newspaper was critical of the slowness of the citizens to get behind Salo. “Now they expand their chests with air and point out to Uncle Louie and Aunt Jane visiting from Brooklyn, ‘See what we turn out here in Passaic?’”

Salo mentioned that most of the runners had teamed up with other runners to jog along with, but he always ran alone. He did his best when out on the dirt highways without other runners near him. He as well as many other runners were scarred and blistered from sunburn on the right side of their bodies after running across the desert.

Each morning the runners needed to show up for a roll call at the designated time. If they didn’t, they received a five-hour penalty. “The runners start at 6 or 7 o’clock each morning and before five minutes have elapsed, they are strung along the roads, some walking, some running, some jogging, others resting and some singing cheerfully as they trot along. They finish at the control point all hours of the night until midnight after which those not checked in are disqualified.”

Struggles through Oklahoma

On Day 37, entering Oklahoma, Souminen pulled a tendon and was delayed as he was brought into a town for medical treatment. He later continued from his stopping point, but soon he lost his overall leader to Payne.

Salo wrote home from Oklahoma, “All last week I was troubled with my knees but I always managed to finish. My right knee is OK now but my left holds me back yet. I believe I will get rid of this trouble soon. I have a set pace and always finish in the first 20 at control points.” He also sent a diagram of the custom shoes he liked with heavy, thick soles and large rubber heels.

While in Oklahoma, disaster struck Salo. For a week he had stomach issues, which he said was dysentery. It cost him many hours including fourteen hours on one day. Pyle had recently imposed a new rule that if a runner didn’t complete the daily stage by midnight, they were out. Salo finished a stage after midnight. Pyle realized how popular and important Salo was to his race, so he rescinded his rule.

Salo said that he couldn’t sleep or truly eat for a week. During this low time, he went three weeks without a bath and he said, “Many a night I crawled under my blankets at the end of the day’s run and stayed there too tired to get up for supper.”

After more than 1,400 miles at Bridgeport, Oklahoma, with about 70 runners still in the race, Salo had held onto 3rd place but still struggling 20 hours behind the leader Payne and losing more time each day.

Before leaving Oklahoma, fellow Finn, Souminen dropped out. When asked who he thought would win, he picked Salo. His reasoning was, “Salo is probably more accustomed to running on pavement than any of the men now in the race. He will make good time and should stand the strain of the hard road grind ahead. If he reaches St. Louis in good condition and still remains among the first ten, I don’t believe anyone of them can beat him out in the final spurt to New York. As for the rain, the more it rains the better Salo likes it. He’s a genuine mud-horse.”

Missouri

On day 48, Salo entered Missouri and was about 32 hours behind Payne, but had fully recovered. A few days later he demonstrated his skill running in the rain and mud, finishing 2nd in a 44-mile run toward Springfield Missouri. His speed had returned and he covered a 45.6-mile stage in 7:07. Everyone could see he was running stronger. In Illinois, he had reached 2,173 miles in 396 hours, averaging about 5.5 miles per hour during the stages. But he was still 32 hours behind the second place bearded Brit, Gavuzzi.

As Salo reached the pavement, on day 58 at Springfield, Missouri, he won a 26-mile stage in an amazing fast, 3:01. He followed that up with a 4:12 50 km stage. The wins that started to come were impressive, but everyone wondered if he could he make up for all of his lost time from Oklahoma before the finish at Madison Square Garden in New York.

Illinois

A reporter from his hometown interviewed Salo. “Salo is very sure that if all goes well his chances for overtaking the leaders are very good. He is very brown looking, almost like an Indian, and seemed to be in superb physical condition. In conversation Salo is very modest and talks with reluctance about himself. He does not seem to think that what he is doing is really a big thing, but his performance today has put his name before everyone in Chicago.”

The reporter next went to interview the famous Finn trainer, Hugo Quist, who had been helping Salo during his transcontinental run. A patrol car with Quist onboard covered the route every hour or two, looking for crippled runners. He believed Salo could still win. He said, “John is one of the best runners I have ever had in hand, in respect to following advice and instructions.” He reasoned that the hardest part of the race was ahead, that the real competitive running would now begin and the mountains would require the utmost strength and endurance. He knew that Salo was the best equipped of all the runners in this respect.

Indiana

Salo had lost twenty pounds since the start of the race, weighing in at 142 pounds at Butler Indiana where he finished the leg in 2nd place on a 41.8-mile stage. He had reached 579.7 miles in 454 hours. He finally fired his trainer who he said was a “habitual drunkard” and had not helped him for three weeks. He had a new helper, but no car. While the other runners had a crew to support them, he had to get water along the route by himself, losing valuable time. He was only getting $1.50 per day from the race for food, getting only one meal per day.

It was reported, “Salo claims that trainers of other runners would ride along slowly along the side of him and pour water out on the ground in front of him, trying trickery in every way to effect his brain and discourage him.” He wished for a tough American Legion man to come out and protect him.

Ohio

In Ohio, on the 69th day, Gavuzzi, the race leader was suffering terribly from five infected teeth and had to stop at a dentist’s office for treatment, losing two hours of his lead of six hours over Payne. Gavuzzi soon had to drop out and Salo moved into 2nd place. Salo also won a 64.7 mile stage to Freemont, Ohio, in 8:58. He was gaining time, but still 24 hours behind Payne.

Salo got word that his hometown was getting behind him and he vowed to give all he had to push on at his sensational pace. He said, “You don’t know how grateful I am to the Daily News of Passaic for planning to send me an automobile. I have a trainer, but he has to depend on outsiders to give him a lift from town to town and I ate very little.”

How was Salo’s family doing during his long absence? His wife, Amelia was very appreciative of the new help he was receiving from their town. She was getting along alright and was doing her best to provide some aid to Salo. “Leo and Helen are the envy of the pupils at school but they are merely attending to their studies, confident in their daddy’s ability to ‘come through.’” Leo was promoting the idea in his neighborhood that perhaps his father was going to be made president of the United States.

On the road after a stage, a stunned reporter wrote, “He reluctantly uncovered his feet to me when I asked him about his physical condition. His toenails were falling off. There is a little swelling in his left ankle, but otherwise his feet and legs are in find shape to run.”

After driving day and night without stopping except to eat and refuel, the car from Passaic was delivered to Salo’s new capable trainer, George Mattison near Elyria, Ohio. When Salo saw the New Jersey license plates, he was thrilled. He gained another hour on Payne that day. With a car, Mattison was now able to give Salo advice and comfort along the route, along with water and food without stops. Others arrived from Passaic joining his caravan, including an American Legion bodyguard. Too bad this great help arrived so late, there was only 12 days left in the race. He was still 22 hours behind.

His new friends from home observed that others were jealous of Salo’s abilities and tried to hurt his chances to win. “Every night he is forced to appear in Pyle’s sideshow at 9 p.m. getting from bed to appear, and sometimes not getting back again until midnight. At the start they always see if there is something they can find fault with about him. It has come to the stage where Johnny is afraid to take a drink from anyone but his trainer or those in the trainer’s party. He sleeps apart from the other runners, more for convenience than anything else.”

But Salo was very popular among the fans and Pyle went out of his way to help him. Pyle even planned to modify the course so it would go through Passaic. Thousands of Finns residing in Ohio along Lake Erie came out to cheer. “It is a holiday every time the caravan of humans moves through a town. Flags are displayed. School is let out and restaurants and hotels raise their prices. Thousands lined the streets cheering wildly.

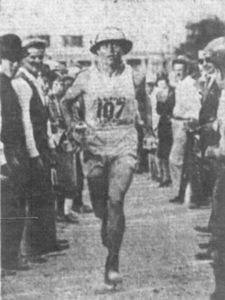

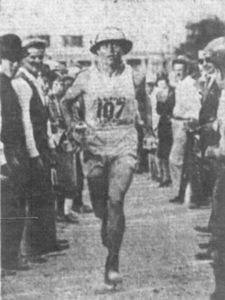

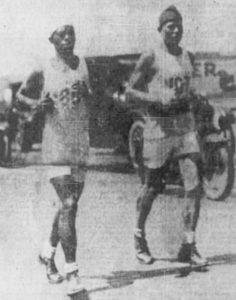

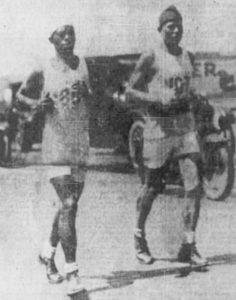

It was observed, “Johnny is easily the best of the lot. He runs without effort, not in a plodding style and at the end is not winded. Wherever he goes thousands turn out to greet him. Admirers by the hundreds ask for his autograph.”

During a stage, Salo and Payne ran together for 30 miles “talking to each other and halting momentarily while one or the other trainer handed out water or some other drink. That day Salo made no attempt to draw away from Payne who was content to remain with his nearest competitor.” They became good friends and respected each other.

Even though the hills were drawing near which Salo did well in, reality was setting in that it was almost a hopeless task to overtake Payne’s huge lead. He could gain an hour each day and still finish in 2nd place.

New York

On May 17th, the runners entered New York State. Salo had recently only been gaining a few minutes each day on Payne who was being very careful walking up and down hills to avoid shin splints. If Payne could avoid injury, Salo wouldn’t make up 20 hours with 400 miles to go. Salo still held onto hope and said, “First place is my fondest hope. I have a wife and two children. My wife has worked to keep things going while I have been running so that we will have a better future than the hard sledding of the past. I may have to be content with second place.” Still, second place winning $10,000 would be significantly financially rewarding The top ten places were supposed to share prize money of $48,500.

Salo won a tough stage in the rain dressed in a fisherman’s coat and hat, feeding on cheese sandwiches, hot coffee, lemon soda and soup. He was said to be “brilliant” in the rain. He “raced about and down the long hills in easy fashion and wasn’t bothered about the heavy rain that fell during most of the trip.” Only 55 runners remained in the race.

Salo was in good spirits and often joked with his crew. “He once glanced at the car, with his name and number painted all over it and asked, ‘Who is this fellow Salo” He’s getting advertised enough.”

Salo gained 1:23 on Payne in central New York after a 72-mile stage to Bath, New York and was about 18 hours behind overall. He said, “Payne is way up in the lead and it’s almost impossible to catch. I’m going to keep trying though. Anything can happen in this race and I’m going to be prepared for it when something does happen.” Payne said, “I’m not taking any chances. I have a good lead and I’m going to keep it.”

Salo was getting more and more attention from the public and demands were made upon him to attend receptions in the various cities where they stopped. “He certainly did not like the parties, but Salo is a good sport, does not want to hurt the feelings of these kind people and goes along. He is the best runner in the race. If he had the help he has now, at the start, an airplane couldn’t catch him.”

Salo won a very long stage or 74.6 miles, covering it in a stunning 12:13, lowering the lead to 16 hours. However, the next day he severely twisted his ankle. Quist gave him some treatment and it seemed to heal quickly, but it was a big concern for this to happen so close to the finish. One runner commented, “Boy, it’s a big country. Columbus was wrong. The world ain’t round. It’s a long flat road.”

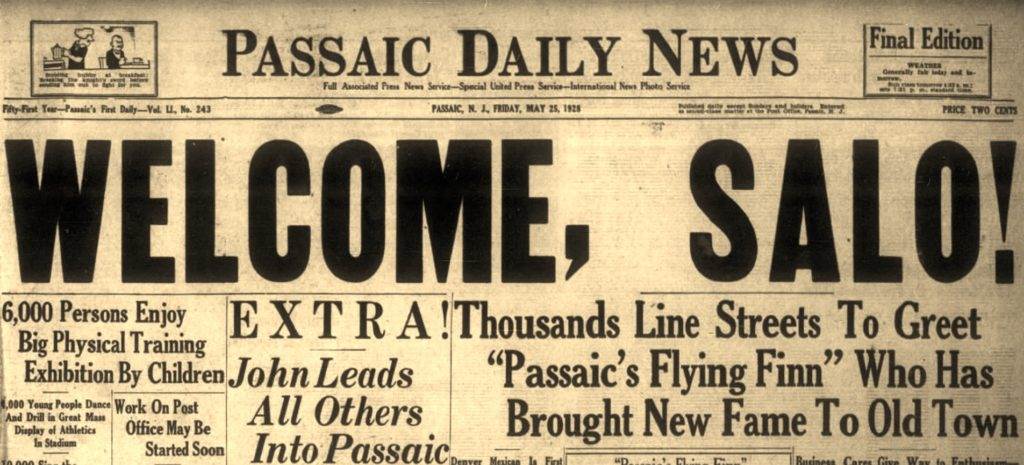

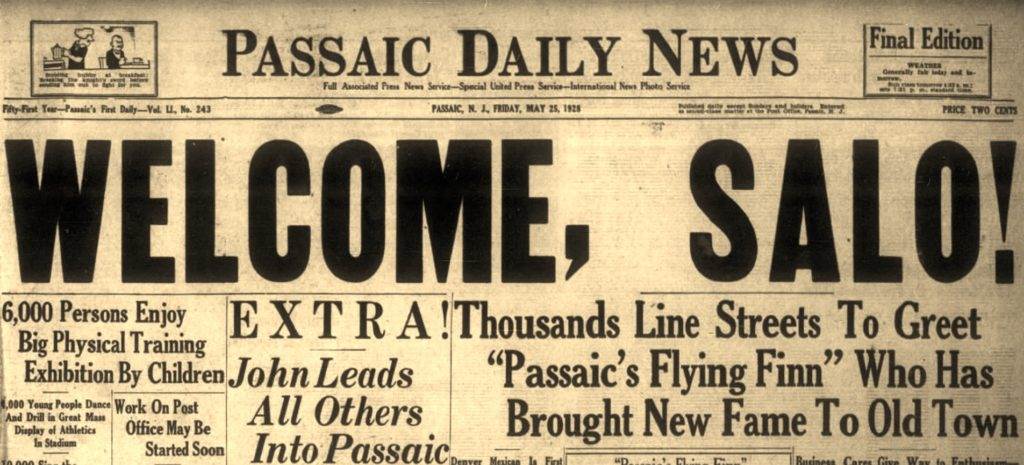

Running through Passaic, New Jersey

C. Pyle went to Passaic. The city hoped that he would have the race pass through their city. Pyle said he would bring the race to the city if he was paid him $1,000. The city had no problem with this demand and quickly raised the funds and paid him half of it upfront.

“All eyes were on Salo when he came marching down Lexington Avenue at a good clip. Whistles blew, automobile horns shrieked, and the great crowds cheered Salo all along the line. In front of Larkey’s store, an enthusiastic youngster rushed through the cordon of police and attempted to pace Salo, got in his way and Johnny had to give him a push into the crowd to prevent a tumble.” He ran into the stadium for the day’s finish and was followed by thousands.

After Salo finished for the day, he was presented with a certificate of appointment to the Passaic police department in front of 4,000 cheering fans. It wasn’t just honorary; he truly was being hired. A city leader said, “This is the least we can do for Johnny Salo for a boy who has done more in the way of advertising the city than any other individual in a long time.”

The reserved Salo stepped up to a microphone (which also broadcast over the national radio) and said, “This is the greatest and happiest birthday of my life. It almost makes me cry to see and hear what the people of Passaic are doing for me.” The other runners were amazed at the warm reception they all received by the city. One trainer said, “I could hardly believe that a city would turn out and pay such a tribute to the runners. Your own boy, John Salo, during the last 900 miles of the race, showed the he is probably the greatest living runner today.”

Salo was on a leave of absence from the Merchant Marines and would wait until after to race to decided whether to accept the police appointment, but he was sworn in at the clerk’s office. Salo had signed a two-year agreement with Pyle for appearances.

Pyle’s side show that night experienced huge crowds, larger than anticipated. “The snake girl, who charms the snakes and chews straw at ten cents a chew got himself a clean shave for the occasion. Kah-Ko the wonder police dog, and Ding-Dong, who removes the tatoo marks on your body in five minutes without any pain, played to capacity audiences.” Also performing was the two-headed chicken. It was actually a normal bird with an artificial chicken head attached to it. Occasionally, the chicken would scratch the fake head and pull it off, to the surprise of the crowds.

The finish at Madison Square Garden

A crowd of about 10,000 people were outside Madison Square Garden cheering as Salo entered the arena in the evening where a disappointing small crowd of less than 2,000 people cheered the runners on inside the arena that could seat 12,000. The runners had to reach the finish by running 200 laps. The larger crowd outside didn’t want to pay the 25 cents to come in. Salo demonstrated to the numerous amateur club officials, runners and coaches that he was one of the sturdiest runners in the world.” He ran hard and covered 100 laps while Payne covered 50. A one-mile sprint was held along the way for $100, but only a few runners were really interested. James Pollard of Reno won the $100.

A New York columnist who called the finish, “lunacy at the garden” commented on “the funny arm motion of Johnny Salo, who seemed to waddle around.” He also was surprised to see the runners stop to buy soda pop from a vendor at one end of the Garden because he knew it was “the worst thing that a runner could possibly do.”

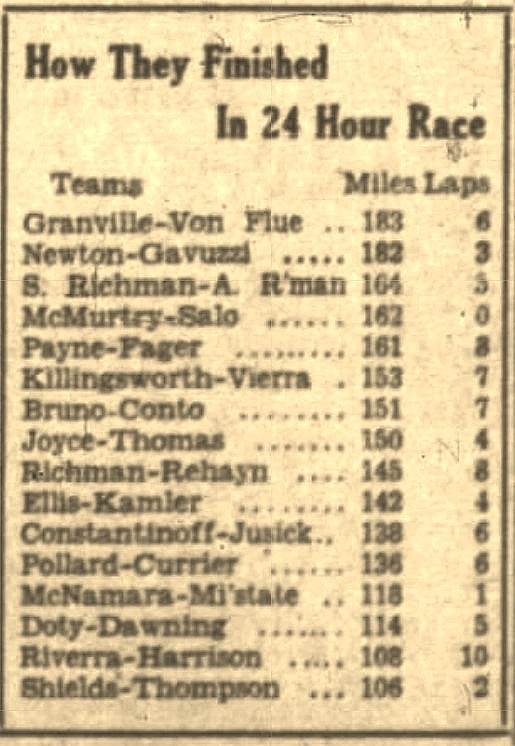

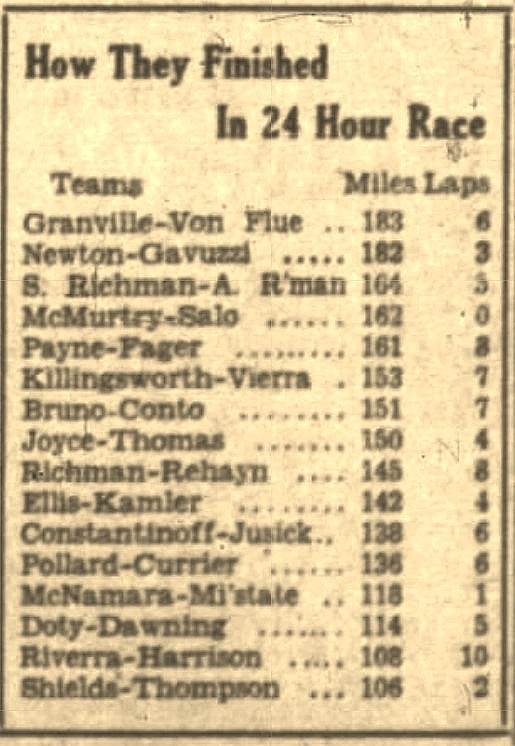

With three laps to go Salo cut loose in a sprint which caused the small crowd to go wild. He won the final stage, escorted by New Jersey police, and came in 2nd place overall. Photographers and reporters were eager for his attention. For most of the other runners they would just finish and walk away. A total of 55 runners finished the 3,423.5 miles in 84 days.

Celebrations

Andy Payne was the overall winner and the next day went to Washington D.C where he was congratulated by President Calvin Coolidge. He soon gave up running.

Two days after finishing, Passaic’s new hero was honored at a banquet at the Elks Home. He walked to the banquet followed by a huge crowd. “No longer was it a determined Salo with part of the long grind before him, but a broad-smiling, embarrassed, and healthy Salo who had won many honors and had a big future before him.” Salo said, “I can’t express what I have in my heart. I can’t say much, the way I feel now, but I do want to thank you all. I tried to do my best for the City of Passaic and my family.”

More racing and appearances

At home he made appearances at baseball games, running races, other sporting events, and spoke to many groups.

On June 27, 1928, he made his first appearance in his police uniform. His influence on the youngsters in his city was impressive. “Every kid knee high to a grasshopper is preparing to win one of the modified marathons that will be conducted on the Fourth of July, and the older boys are working up steam for the long grind from Spring Valley to Clifton on the same day.”

He used the prize money to buy a house for his family on Spring Street and settled down to walk a police beat. “For Johnny, dreams did come true. He had become the ‘flying cop from Passaic,’ a local hero.”

A comparison was made, “After Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic everybody who had ever been in a plane and several who had not, made preparations for a flight. In this case Salo’s work stimulated interest in one of the greatest of all sports, running.”

About two months later Salo was interviewed and ask how he felt. “My legs are fine, but I haven’t felt right since the race finished. I always want to rest and every time I sit down I want to go to sleep.” However, “Salo takes a long run two or three times a week and his time compares favorably with his time last year before he started the cross-country grind. He plans to enter several races which will be held in the winter.”

Passaic merchants held a “four cent Salo” sale in the fall, recognizing the four cents that Salo was down to in Arizona.

In March 1929, Salo announced his intention to get a leave from the police to again run in the Bunion Derby that would this time go from New York to Los Angeles, against the wind. An editorial in his hometown newspaper thought the idea was terrible. “For a long time after his return he was not altogether a well man Salo shouldn’t think of going into another such nerve-wrecking, body-breaking test of endurance. For his own sake and his family’s, he should to be dissuaded from making this next race. His sturdy physique, weakened by the last effort could be shattered in the next.”

This story continues here: Johnny Salo – 1929 Bunion Derby

Sources

- Geoff Williams, C. C. Pyle’s Amazing Foot Race: The True Story of the 1928 Coast-to-Coast Run Across America

- Charles B. Kastner, The 1929 Bunion Derby

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Aug 13, 1919

- The Herald-News (Passaic, New Jersey), Jul 22, 1968, Aug 16, 1973

- Passaic Daily News (New Jersey), Oct 5, 1922, Mar-Aug, 1928

- Daily News (New York, New York), May 27, 1928

- The Morning Call (Paterson, New Jersey), Mar 18, 1929