By Andy Milroy

In 2018, Nao Kasami of Japan won the Lake Saroma 100km in a world best time of 6:09:14 on a significantly wind-aided 100 km course. A wind-aided course like this, has caused statisticians to look again at the way 100 km times are interpreted and understood. Wind-aid offers a real problem. Is a good time due to a strong effort by the runner or just due a strong tail wind? It is time to look again at the fastest non-aided 100 km performance, the forty year old track mark of 6:10:20.

The clash of the giants

For much of the second half of 1978, there had been keen anticipation to discover if Don Ritchie of Scotland could match his 6:18:00 100 km road mark set in June at Hartola in Finland, in the forthcoming Road Runners Club 100 km promotion on the track to be held in October at the Crystal Palace in England. Ritchie had set out to run fast in the Finnish race with the intention of surpassing the 6:19 that he thought Cavin Woodward of England had run just a fortnight earlier in Migennes, in France. That report was garbled and incorrect, Woodward had “only” run 6:26:05!

In his biography, Ritchie wrote that he planned on running the Hartola race hard and fast. He did not want to make a habit of running 100 km races!

Cavin Woodward’s current 100 km world best (6:25:28) was due for revision because he had set that time en route to running a then world 100-mile best of 11:38:54, set in 1975. The 6:25 had surpassed the week-old previous world track best by Germany’s Helmut Urbach of 6:59:57.

Since the his 6:18 run in late June 1978 on a tarmac and dirt road course, Ritchie had lost twice to Woodward, at the 36 miles Two Bridges in Scotland and the Woodford to Southend 40 miles in London. Woodward was in very good form that year, attempting a world track best at 40 miles in April, setting a new course record in the tough Isle of Man TT 40 miler on a new longer course, winning the Migennes 100 km in 6:26:05, taking the Two Bridges in 3:24:45, the second fastest time ever on that course (Ritchie back in 5th 3:32:49) and the Woodford 40 miler had been won in humid conditions in 3:50:14 with Don Ritchie in second in 3:59:35. Thus Woodward was unbeaten over ultra-distances before the Brighton race.

1978 London to Brighton

But in September 1978, in the London to Brighton, the balance between these two great runners perhaps shifted. Woodward made his usual fast start and was nearly a minute clear of the Scotsman at one point but Ritchie caught him after 30 miles. At around this point Woodward heard that his car, which was carrying his drinks, had broken its camshaft. Worrying about how he and his family were going to get home to Warwickshire, and how he was going to get his drinks, he momentarily panicked, accelerating sharply. Ritchie let him sprint away, content to reel him in slowly. After he drew along side he was able to move away from the winded Woodward, whose race had been badly disrupted by the news. Woodward’s drinks had been moved to another car, so that problem at least was solved.

The record for the Brighton course had been strongly contested in the 1970s. First the record was revised by the 21-year-old South African, Dave Levick. Alastair Wood broke that mark in 1972, with Joe Keating narrowly missing the record in 1973. The 53.5 mile course was a mile longer than that on which Ritchie’s fellow Scot, Alastair Wood, had set his course record of 5:11:08 in 1972. For this 1978 race, Ritchie finished with 5:13:02, with Woodward clocking 5:18:30. The 5:13 was effectively a new course record, worth perhaps 5:09 on the old course.

Preparing for the 1978 October 100 km

Within a week, Ritchie recovered well from the Brighton race and ran several shorter races over the next month. A week before the track 100 km, he ran a 26 mile glycogen depletion run. Clocking excess of 20 miles a day in training until the Wednesday, when he began to carbo-load. On Friday he began the long train journey from Forres in the north of Scotland down to London.

On Saturday, the 28th of October, Ritchie had a cup of tea and three rich tea biscuits for breakfast before travelling to the Crystal Palace stadium in South London. There he was once again going to race Cavin Woodward who would be seeking to defend and perhaps improve on his own world 100 km record. Also in the race was the Irish Olympic marathon runner, Mick Molloy, who in 1974 had set a world 30 miles record of 2:44:47, beating Ritchie.

Woodward had been in excellent form that year, as we have seen, recovered from the groin injury which had been affecting him for some two years since his great 1975 multi-world record 100-mile run at Tipton, England. It was just whether the loss in the Brighton had dented his confidence. Ritchie had the fastest 100 km time in the field and had broken Woodward’s 100-mile record in 1977 at the Crystal Place. His very good run in the Brighton beating his rival may have helped to neutralize mentally the earlier defeats in the Woodford and Two Bridges. Both men had marathon bests that dated back some years. Woodward’s was the faster, 2:19:50 in 1973, with Ritchie’s 2:23:31 best set in 1971. Based on those times, once again Woodward had the edge.

The addition of Molloy to the field added uncertainty. The former Olympian was an unknown at distances beyond 30 miles but his 2:18:22 marathon speed meant he could potentially be dangerous. Mike Newton was also in the race. He had won three Continental European 100 km races in three different countries in the previous six months. The outcome of the race looked unpredictable.

The Race

Mist made it impossible to see the far side of the track when the race began at 9:30 am. Mere mist could not inhibit Woodward’s usual aggressive start and he reached five miles in 27:21, but both Ritchie and Molloy followed him closely. Woodward continued to lead, reaching 10 miles in 55:28 and when at 20 miles, Ritchie was forced to leave the track for a pit stop, he and Mick Mollloy quickly opened a gap of a lap and a half, both going very strongly.

Ritchie quickly showed his competitive credentials. Once back on the track, he quickly closed on the leaders. Pushing on, he pulled the Irishman with him only to be faced by a strong response from Molloy who then led through the marathon in 2:29:46 and 30 miles in 2:51:54. Ritchie was in third place at 50 km, which he passed in 2:59:59, Molloy leading with 2:58:22 and Woodward in second on 2:59:52. Ritchie however took the lead shortly after, when Molloy left the track for some minutes. The new leader took 29:08 to run the next five miles.

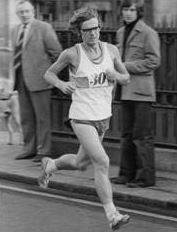

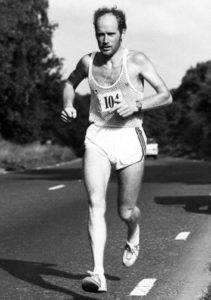

(When I first saw Ritchie in action a year later, my impression was of a savage beast which had just been unleashed. Another author has described him as a “mananimal”. The 34 year old Scot was probably at his physical peak.)

The 40 mile mark was passed in 3:52:55 and by that time, Ritchie had pulled out a close to four-minute gap on Woodward. It took him just over a hour to reach 50 miles, where he broke Woodward’s existing 50-mile world best of 4:58:53 (split time during his 1975 100-mile world record) with a time of 4:53:28, by five and a half minutes. Ritchie continued to run at close to 10 miles an hour and became the first man to run 60 miles in under 6 hours – 5:56:57. His last lap for the 100 km took just 88 seconds and he took fifteen minutes eight seconds off Woodward’s 100 km world record, running 6:10:20. He had also run over seven minutes faster than his road mark at Hartola.

At 30 miles Molloy had looked in contention for the 40 mile world record but his feet became so painful he had removed his shoes and ran the rest of the race in socks. He completed the 100 km but took half as long again for the second 50 km to his first. Woodward had also left the track briefly, but managed to complete the race in a time which few could match (6:38:48) reaching 50 miles in 5:04:54. Mike Newton, running his fifth 100 km race in six months, passed 50 km in 3:08:03 and 50 miles in 5:15:51 before completing the distance in 6:48:08.

100 km Results

1. Don Ritchie 6:10:20

2. Cavin Woodward 6:38:48

3. Mike Newton 6:48:08

4. Jan Knippenberg NED 7:07:50

5. Mick Molloy IRL 7:26:11

The above were the only runners to cover 100 km within the eight hour time limit. Don Ritchie’s 10 mile splits were 55:28, 59:26, 58:51, 59:10, 60:33 and 63:29. A fuller list of Don Ritchie’s splits: 10km – 34.06, 20km- 1.09.21, 30km – 1.46.55, 40km – :23:12, 50km – 2:59:59, 60km – 3:36:29, 70 km – 4:13:59, 80km – 4:51:48, 50 miles – 4:53:28, 90 km – 5:30:45, 97.2 km at 6 hours, 100 km – 6:10:20 [The 6 hour distance is now also recognized as a world best.]

Ritchie led at 10 km, joint first with Woodward at 20 km, 3rd at 40 and 50 behind Woodward and Molloy. Marathon Ritchie – 2:31:13 , 60 miles 5:56:57

Fastest road 100 km

The fastest non-aided road 100 km was set on a loop course (Winschoten NED) by Jean-Paul Praet BEL in 1992. J-P Praet’s splits: 10 km 35:45, 20 km 1:11:15, 30 km 1:47:57: 40 km 2:26:07. 50km 3:03:53, 60 km 3:41:59, 70 km 4:20:16: 80 km 4:58:45, 90 km 5:37:02,

100 km 6:16:41. Praet led from early on. Konstantin Santalov was second at 50 km 3:06:26. 12 Sept 1992

The top road 100 km performances set on non-aided courses

6:16:41 Jean-Paul Praet BEL Winschoten 12 Sep 1992

6:17:17 Takahiro Sunada JPN Belves 30 Apr 2000

6:18:09 Valmir Nunes BRA Winschoten 16 Sep 1995

6:18:22 Hideaki Yamauchi JPN Los Alcazares 27 Nov 2016

6:18:24 Mario Ardemagni ITA Winschoten 11 Sep 2004

6:18:26 Vasili Larkin RUS St Petersburg 07 Sep 2013

6:19:20 Steve Way GBR Gravesend 03 May 2014

6:19:54 Yamauchi – 2 Sacramento 04 May 2019

10 km Splits

- Praet – 35:45, 1:11:15, 1:47:57, 2:26:07, 3:03:53, 3:41:59, 4:20:16, 4:58:45, 5:37:02, 6:16:41

- Sunada – 35:14, 1:11:47, 1:48:15, 2:26:09, 3:03:06e, 3:39:22, 4:16:46, 4:59:36, 5:37:17, 6:17:17

- Nunes – 36:21, 1:12:44, 1:48:58, 2:25:40, 3:03:40, 3:41:59, 4:20:59, 5:00:32, 5:39:20, 6:18:09

- Yamauchi – 2016 – 39:05, 1:17:22, 1:55:02,2:32:53, 3:09:27, 3:45:06, 4:21:48, 4:59:51, 5:38:34, 6:18:22

- Ardemagni – 38:00, 1:15:40, 1:53:20, 2:31:11, 3:07:45, 3:44:40, 4:22:00, 5:00:26, 5:39:10, 6:18:24

- Larkin – 4 km loop – 36.31e, 1:13:47, 1:51:04e, 2:28:02, 3:05:39e, 3:43:42, 4:21:56e, 5:00:22, 5:43:36e, 6:18:26

- Way – 37:53e, 1:15:38e, 1:53:11e, 2:30:30e, 3:07:18, 3:44:11e, 4:23:16e, 5:01:58e, 5:41:11e, 6:19:20

- Yamauchi – 2019 – 36:04e, 1:11:58e, :47:55e, 2:23:55e, 3:00:34, 3:38:05e, 4:16:09e, 4:56:14e. [50 miles 4:57:44], 90 km 5:37:31e, 100 km 6:19:54

Note: Nao Kazami’s 6:09:14 in 2018 was set on the Saroma course with a strong following wind – two to three times the allowable limit for sprinters.

Why has the 6:10:20 record lasted for 40 years?

Ritchie’s 6:10:20 has remained unsurpassed by a non-aided mark for over forty years. This is perhaps for several reasons. The Crystal Palace race saw two great ultrarunners in very good form go toe to toe, with a formidable marathon runner adding more to the mix. Ritchie was only third at at the 50 km point, he was in a highly competitive race against strong competitors who had beaten him before. When he pushed hard enough to create a gap, he had to continue to strive to maintain and increase it. Ritchie’s great strength was the ability to sustain a pace over a long period, only very gradually slowing. Too often one great runner does not have the support of such sustained competition in a race. Moreover, unlike a road race, Ritchie always knew exactly where his opponents were. But he also knew how formidable an opponent Woodward was, he would never give in and would dig deep late in the race.

I asked Don Ritchie years later why he had run so fast, he ran ten minutes or more faster than he needed to break the record, his reply was “Cavin Woodward was chasing me.”

But strong, sustained competitive pressure is not enough on its own. Careful and realistic pace judgement is essential. When Woodward had set his 100 km record he had passed 50 km in under 3:01, so the leaders already knew what sort of pace to hit halfway. Looking at the 50 km splits of many of the sub 6:20 marks above, they cluster around 3:04, already giving away precious minutes to Ritchie’s 6:10.

Perhaps one of the most talented ultrarunner operating at the turn of the 21st century was Takahiro Sunada of Japan. He was a member of the Japanese team at the Chavagnes-en-Paillier World 100km Challenge in 1999. Quoting from my 1999 race report “By the end of the first long lap (about 27Km). . . Takahiro Sunada . . . passed 27Km at 1 hour and 35 minutes – which is around 5:51 pace for 100Km! . . . Sunada continued to pour on his incredible pace, completing the second major loop (51Km) in 2:57:47, [around 2:54 pace at 50km] . . . Sunada went through the 60Km in about 3:28 but trouble hit the impetuous race leader at 63km. Cramp reduced him to a walk, and he was forced to take a massage in a medical tent at 76km. [At the 70km point he had a 20 minute lead over the second placed runner!]” Despite the blitz start, walking and a massage, he still finished up third in 6:26:06! Arguably Sunada went out too fast to the 50 km, so there is a delicate balance. He was five minutes faster than Ritchie at 50km, perhaps eight at 60 km. Sunada’s start was definitely too fast. 5:51 pace for the 100 km is not sustainable. But he was on his own, he did not have experienced rivals racing with him who could run at his pace. Sunada was a 2:11 marathon runner at that stage of his career, he was to improve to 2:10.

Ritchie had Woodward racing with him at 50 km, racing at a pace at which they were comfortable. With numerous London to Brighton races behind them, at that time viewed as an unofficial Ultra World Championships, attracting top runners from across the world, racing at such tempo was not unusual. Woodward has also run the Comrades. Within the relatively small community of such runners in the U.K. and within a reasonably compact country, the elite runners would race each other frequently. Woodward habitually would go to the front of a race and run as hard as he could for as long as he could. When he first began this strategy, often he would crash and be overtaken. Eventually his body adapted and he did not come back, so the best U.K. runners got used to going out fast with him. It made for fast races.

Moreover there were relatively few ultramarathons back in the 1970s so most runners also competed regularly in marathons. The faster marathon running tempo carried over into ultramarathons. Nowadays there are many Ultras, so runners are able to specialise but get used to running at a slower pace. In the 1970s and earlier, races beyond the marathon did not have a distinct identity, they were seen as longer marathons. It was Ted Corbitt who coined the terms “ultrarunner”, “Ultramarathon” and “Ultra Distance”. Don Ritchie was not to hear the expressions until he visited San Francisco in December 1979.

The possibility a sub 6 hour 100 km

There has been talk of runners running a 100 km in under 6 hours. The nearest anyone has come on an non-aided course is Don Ritchie who ran 60 miles in under 6 hours. (Actually 97.2 km/60 miles 699 yards) His 100 km was 6:10:20. Effectively a runner would need to run substantially under three hours for 50 km and then finish the next 50 km in close to three hours. This needs very good basic speed, excellent pace judgement and serious competitive pressure.

There is also talk of what a 2:03 or 2:04 marathon runner would achieve over the 100 km distance. This deserves closer examination. The physiological processes for the two events are distinctly different. In the Marathon a runner burns glycogen and eventually fat in the closing stages. Over the 100 km a runner needs to burn fat efficiently and will probably need to take on carbohydrates as well. The 100 km is well over twice the length of a marathon.

Only one Kenyan has made serious attempts at the 100 km, Japanese based Erik Wainaina (once a 2:08:43 marathon runner.) Despite six 100 km runs on the Lake Saroma course, the fastest he has run is 6:38:40. For the often slight Kenyans and Ethiopians the additional strains and stresses of running a 100 km are very hard. The more robust Southern African runners from South Africa, Botswana and Lesotho have adapted better. The fastest 100 km by a African is 6:24:06 by Bongmusa Mthembu RSA. Other South Africans, Philemon Mogashane and Livingstone Jabanga have also run faster than Wainaina on non-aided courses.

The Comrades, with its substantial prize money, is the attraction for South Africans, giving them a natural transition to the 100 km. For Kenyans and Ethiopians to run the 100 km would also mean an extended recovery time, which would substantially reduce their potential earning capability. As yet there simply is not the prize money in ultras to attract the East Africans and provide the incentive to overcome the greater physical demands and significant recovery time. Those with long memories will recall that the move up to the marathon took the East Africans years to manage and master.

The winner of the New York Marathon in 2:09 and a 2:08 marathon runner Willie Mtolo ran the Comrades four times, finishing just second once. Fast marathon runners – Ian Thompson (2:09:12) and Alberto Salazar (Boston 2:08:52) won the London to Brighton and Comrades respectively, but only ever tackled the one ultra.

Perhaps the most successful fast marathon runner to tackle Ultras was Takahiro Sunada, originally a 2:12 performer. He improved his marathon best each time after running a 100 km, going down to 2:11 and then 2:10. Sunada ran 6:17:17 on an non-aided course (see above), and 6:13:33 at Saroma. When he attempt to run faster at Chavagnes-en-Pailliers in 1999 he set out too fast, clocking around 2:54 at 50km. He hit trouble soon after 60 km. Yet in order to run sub 6 hours he needed to probably run even faster by 50 km to allow some degree of slowdown over the second half. His fellow Japanese Hideaki Yamauchi showed negative 50 km splits are possible in a sub 6:20 in 2016, 3:09:27/3:08:55. Arguably at Sacramento in 2019 he attempt this again, reaching 50 km in 3:00:34, on schedule at 50 miles he slowed to 3:19:20 in the second 50. His negative splits in the World 100 km at Los Alcazares in Spain in 2016 were driven by fierce competition over the later stages from South African runners; Bongmusa Mthembu was to set a national record in second place. So a second factor, sustained competitive pressure is needed.

So why has no runner come close to Ritchie’s 6:10:20 100 km set over 40 years – on a non-aided course? Often things happen because the right person is in the right place at the right time. Ritchie was in very good form. Woodward was in very good form. They were used to racing fast, the building blocks had been put in place over the pervious decade. Neither Ritchie nor Woodward focussed on the marathon, but the former had a personal best of 2:23:31 not far from Woodward’s 2:19:50.

The highly competitive Two Bridges race demanded sustained speed up to 60 km; a popular race that attracted top marathon runners too. Both Ritchie and Woodward were used to running 40 miles in close to 3:50 on both track and road. It was, once again, a very popular distance, an extended marathon that could run hard. The London to Brighton also gave good grounding over 50 miles plus against top international competition. Yet the longer events (Ultras was not then used as a term as I have said) were not common, so the top runners regularly ran marathons competitively, thus retaining their leg speed.

The race environment at Crystal Palace, in October 1978, was good with favourable weather conditions, strong competition and with a tough but achievable target of Woodward’s 6:25.

Both men had run world record 100 mile times, both had very strong 100 km road marks that year, (ranked one and two on the road all-time list by German Statistician Heinz Klatt), both were confident of victory, yet both knew the other had the ability to win the track race in record time. Ritchie knew he had run faster than Woodward’s listed world track record for 50 miles of 4:58 in the Brighton, probably below 4:53. So both men had the confidence, the experience and the ambition to set out to break the world track records, at least at 50 miles. The competitive pressure generated by each on the other, meant that confidence was tinged with uncertainty born of respect. Even when Ritchie was out in front, he could not let up, he knew that Woodward was there, chasing, waiting.

So the 6:10:20 is the result of a unique set of circumstances, when three ultra world record holders met, each with the ability and confidence to set new world marks. If Ritchie had eased off, content with 6:20 clocking, that would have given Woodward the incentive to challenge the race leader.

We have noted the marathon bests of Ritchie, Woodward and Molloy. Forty years later are faster marathon runners testing themselves over the 100km distance?

Marathon personal bests for top 100 km runners

Having seen so many good runners crash and burn in the frenzied cockpit of the World 100 km, the problem for the faster runner is not getting sucked into the fast early pace of the race, when such a pace feels comfortable for them. The discipline instead is of running at a slower pace that can be sustain with reasonable slowdown to the finish. Basically pace judgement. But testosterone and adrenaline tend to screw that up on the World stage for male runners. The faster the runner, the faster the normal pace at which they operate, and the greater can be the difficulty in scaling back that pace to one sustainable for the 100 km. This is why running preparatory races at the stepping stone distances of 50km, 60 km and 40 miles are so useful.

There does appear to be a correlation of sorts between the 100 km and marathon. Runners with sub 2:20 marathon personal bests, were often not running those sort of times immediately before or after their best 100km. The marathon times for elite 100 km runners look more homogeneous. Takahiro Sunada was unusual. His marathon PR was 2:12:01 before he ran his first 100 km – 6:13, he then improved to 2:11:03, ran 6:17:17 and then reduced his marathon best to 2:10:08, virtually straight after. The assumption would seem to be that he was benefiting from improved fat burning following running each 100 km.

This actually also happened to Ritchie, his 2:22:48 split (see below) was a PR and was the marathon distance run after to his 100 km(6:10:20), this was a split in his 50 km world best of 2:50:30 in March the following year. In 1983 Ritchie ran a world record of 4:51:49 50 miles in March, then he ran 2:19:35 in London in April, his best marathon time. Thus Sunada and Ritchie both ran personal bests for the marathon after running very fast ultras at 50 miles/100 km. Ritchie set a marathon PR of 2:22:48 reasonably close after his 6:10:20.

Looking at the other sub 6:20 runners, their marathon PRs are listed. In brackets are their marathons either immediately before or after the best 100 km :

- Steve Way ran 2:15:16 (2:16.27)

- Nunes ran 2:18:13 [1991] (Nunes does not appear on the sub 2:20:South American marathon list – so his usual marathons were probably 2:20 +) (Still checking.)

- Praet ran 2:25:41 (2:30:31)

- Yamauchi 2:20:43 (2:26:16)

- Larkin 2:21:55 (2:24:04)

- Ardemagni 2:22:21 (2:26:09)

Other winners of the World 100 km have sub 2:20 marathons. Domingo Catalan, who won it twice, was a 2:17:46 marathon runner, his 6:19 at Torhout in the first IAU Championships was on a unverified course. (2:24:29 closer to his 6:19). Konstantin Santalov, winner three times, ran 2:14:56 on a probable short course at Kiev, probably worth 2:17:46 for the full distance. His marathon career is not well known. He ran 2:28:29 close to his faster 100 km runs. Aside from Sunada, other fast marathon runners have not made the transition to running sub 6:20 times.

Here are some more marathon/100 km bests. The marathon time in brackets is that run close to their 100 km best.

- Alberto Di Cecco. 2:08:02#/6:28:48 #suspended for use of EPO

- Erick Wainaina. 2:08:43/6:38:40 (2:28:59)

- Shinichi Watanabe 2:09:32/6:23:11 (2:17:36)

- Ravil Karpov 2:11:07/6:33:46 (2:23:10)

- Giorgio Calcaterra 2:13:15/6:23:22 (2:29:28)

- Anatoly Korepanov 2:13:21/6:32:41 (2:16:45)

- Sergey Yanenko 2:14:32/6:25:25 (2:26:12)

- Pascal Fetizon 2:14:35/6:29:44 (2:21:33)

- Jose Maria Gonzales Munoz 2:14:36/6:23:44 (2:26:34)

- Max King 2:14:36/6:27:43 (2:17:32)

- Andy Jones 2:17:54/6:33:57 (2:19:21)

- Bruce Fordyce 2:18:25/6:25:07 (2:18:37)

- Jaroslav Janicke 2:18:35/6:22:33 (2:27:38)

- Jiri Jelinek 2:19:24/6:25:19 (2:28:26)

- Andrej Volgin 2:19:25/6:20:44 (2:27:43)

- Don Ritchie 2:19:34/6:10:20 (2:29:39 – but had a 2:23:31 PR in Oct 1978)

- Cavin Woodward 2:19:50/6:25:28 (2:34:35, 2:28:47 the week before)

- Igor Tyupin 2:20:18/6:34:18 (2:27:17)

- Tim Sloan 2:20:37/6:29:35**

- Karl-Heinz Doll 2:20:47/6:29:34 (2:25:42)

- Jorge Aubeso Martinez 2:21:34/6:26:38 (2:25:50)

- Thierry Guichard 2:21:56/6:24:26 **

- Jonas Buud 2:22:03/6:22:44 (2:29:25)

- Mikhail Kokorev 2:22:06/6:31:22 (2:24:28)

- Rainer Muller 2:22:56/6:26:56 **

- Bongmusa Mthembu 2:23:37/6:24:06 (2:30:34)

- Simon Pride 2:24:24/6:24:05 **

- Oleg Kharitonov 2:24:24/6:29:29 (2:27:10)

- Kazimier Bak 2:24:52/6:24:29 **

- Bruno Scelsi 2:25:39/6:27:08 (2:28:31)

- Gregori Murzin 2:26:13/6:23:08 (2:37:00)

- Andrej Magier 2:27:50/6:24:11 (2:32:02)

- Shaun Meiklejohn 2:27: / 6:26:58

- Jean-Marc Bellocq 2:29:23/6:26:13 **

** indicates marathon PR took place close to 100 km PR.

It is interesting and perhaps informative to compare the marathon times of the fastest Comrades runners.

- Willie Mtolo 2:08:15/5:33:55 (2:21:10) Mtolo was second behind Kotov

- Leonid Shvetsov 2:09:16/5:20:41 (2:16:19)

- Vladimir Kotov 2:10:58/5:25:23 (2:23:20)

- David Gatebe 2:15:30/5:18:19 (2:20:12)

- Dmitri Grishin 2:17:41/5:29:33 (2:18:18) subsequently ran 5:26 but no marathons?

- Fusi Nhlapo 2:18:24/5:28:53 (2:31:46)

- Sipho Ngomana 2:19:54/5:27:10 **

- Claude Moshiywa 2:21:09/5:32:09 (2:29:02 – not close)

- Ludwick Mamabolo 2:21:19/5:31:03 (2:33:42)

- Charl Mattheus. 2:21:50/5:28:37 ***

- Stephen Muzhing 2:24:51/5:29:01 (2:27:23)

- Edward Mothlibi 2:24 /5:31:33

- Andrew Kelehe 2:26:47/5:25:52 ***

Most of these performances were set under competitive pressure. The opportunity was there to run sub 6:20. But there does not seem to be a strong correlation between basic marathon speed and 100 km times. The evidence at present seems to be that faster marathon runners below 2:13 are usually not able to sustain that kind of speed over into the 100 km and run sub 6:20, or even sub 6:15. Watanabe is a case in point. However I suspect that there may be other factors in play with him, perhaps long term injury. It is a pity Sunada did not have the opportunity to race at Winschoten. Particularly the chance to run under 6:13 on a unaided course.

Why detailed analysis of 100 km marks is necessary

In this analysis of the 100 km, the focus has been on races which were not potentially wind aided. Reliable, comparable data is essential. The IAAF 50% separation between start and finish means that at the Lake Saroma Race in Japan runners are possibly, even probably, benefiting from a strong onshore wind that comes off the sea in the morning. This means uncertainty when examining the results from this race. Are the fast times the result of the undoubted talent of the Japanese runners, or of a strong tail wind?

With global warming, the Pacific is set to get warmer, increasing the strength and frequency of onshore winds in Japan. 2018 saw the biggest typhoons in Japan for 25 years, Typhoon Jebi had wind speeds of a 100 miles an hour. Typhoon Trami had winds of 134 miles/216 km an hour. In recent years there have been far stronger typhoon seasons in the Pacific with more typhoons and a number of “super typhoons” with wind speeds of 240km/150 miles per hour. Such typhoons are just the highlights of systems of stronger on-shore winds buffeting the Japanese coast. Typhoons are, of course, on-shore winds. The results of the Saroma races reflect this.

Takahiro Sunada ran 6:13:33 on the Saroma course but he subsequently ran 6:17:17 and 6:26:06 for 100km on standard courses in Europe. Twenty years later, in 2018, Nao Kazami ran 6:09:14 on the same course but his marathon best is just 2:17:14. So Kazami is SEVEN minutes slower than Sunada at the marathon and yet ran four minutes faster for 100 km on the same course!

Weather information websites recorded a following tailwind of twice to three times that allowable to sprinters, but the effects would have been of much, much greater duration at Saroma during the race.

The massive underlying problem with a potentially wind aided course is whether improvements in times are due to a better runner running faster or more likely just a stronger tail wind. This is why the certainty of Don Ritchie’s 6:10:20 is so important.