Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 34:48 — 38.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

For more than a century there has been a “sport” involving combining ultrarunning with golf. No, this isn’t a joke. In 2016, Karl Meltzer of Utah, who has more 100-mile trail wins than anyone, set a world 12-hour speed golfing record of 230 holes, covering about 100 kms in the process. This created attention in ultrarunning circles, and we were left to wonder, how long has such a thing been going on?

For more than a century there has been a “sport” involving combining ultrarunning with golf. No, this isn’t a joke. In 2016, Karl Meltzer of Utah, who has more 100-mile trail wins than anyone, set a world 12-hour speed golfing record of 230 holes, covering about 100 kms in the process. This created attention in ultrarunning circles, and we were left to wonder, how long has such a thing been going on?

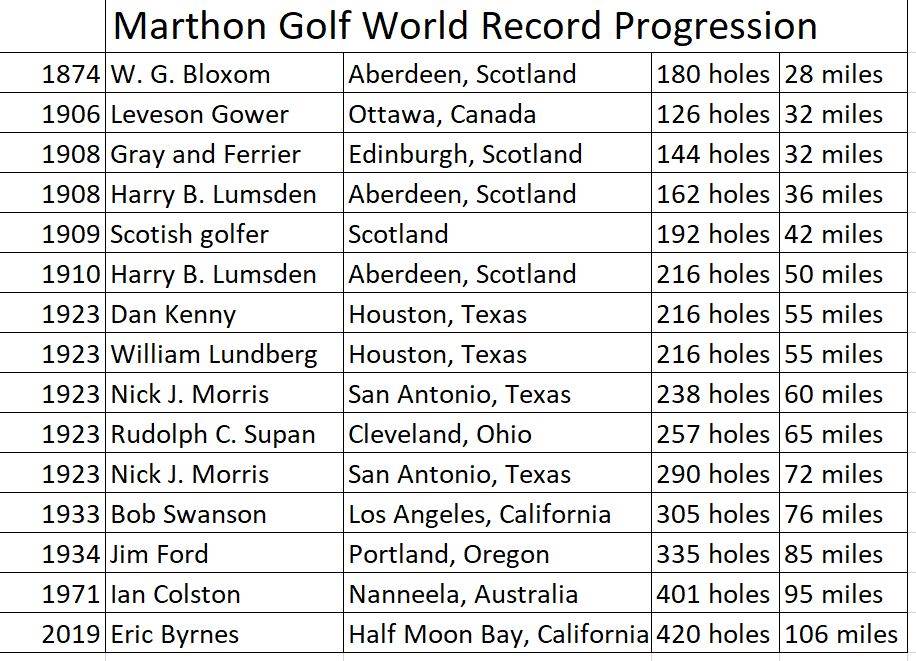

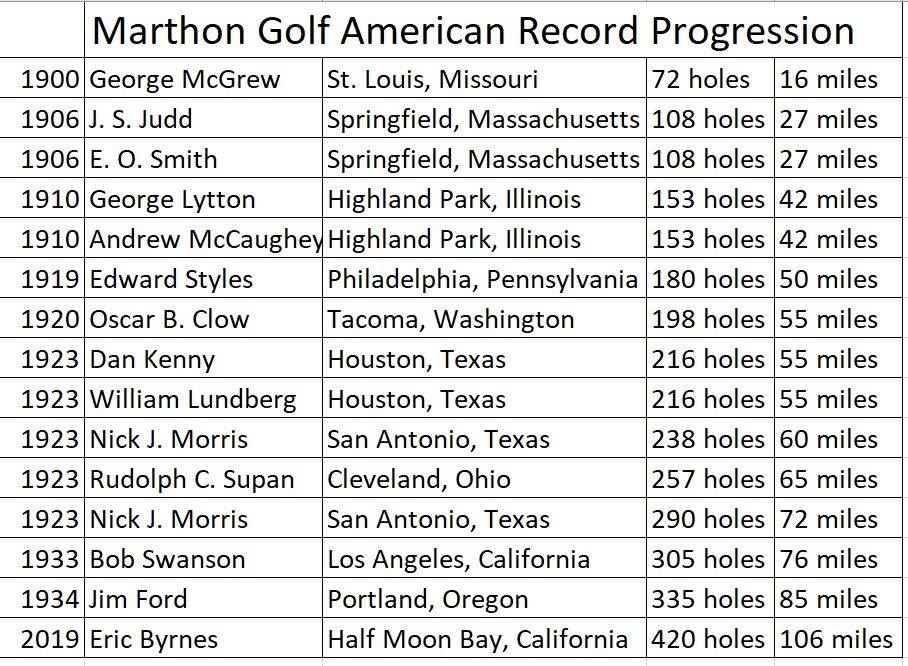

What has been called “Marathon Golf” is the art of playing as many rounds or holes as possible in a certain amount of time, usually a day (24 hours), recording strokes for each round. Golf purists have despised this activity over the years. Ultrarunners are amused and fascinated by it. In 1923 a marathon golf frenzy spread across America and again in 1934 several athletes were contending furiously for the world record.

How many miles is covered by playing a golf round? It depends on the length of the course of 18 holes. Today’s courses average about 6,500 yards. When I run every hole of my local 7,000-yard golf course straight line using a GPS, the distance comes to about 5.5 miles. Today for the average course, an average distance for a round is probably about five miles. Years ago, before golf technology improved, average courses were shorter with a length closer to 4.5 miles. There were, and still are, very short nine-hole courses where playing 18 holes could be as short as 3 miles.

Birth in Scotland

It is believed that marathon golfing was born in Scotland on a bet. In 1874, an Aberdeen Scotland golfer, W. G. Bloxom, wagered that he could play twelve rounds, 180 holes, on a short 15-hole, 2.3-mile course, and then walk ten more miles, all in 24 hours (about 38 miles total). He won the wager.

Bloxom found something he was very good at. Next, he played 16 rounds (96 holes) of the Musselburgh Links nine-hole course, for about 35 miles, against Bob Fergerson. They started at 6 a.m. and finished at 7 p.m. Bloxom averaged a score of 40 for the nine-hole rounds and won five pounds.

While the Scots were perfecting their marathon golf skills, a golfer in Canada also wanted to golf an entire day. On June 19, 1906, Canadian, Leveson Gower, of the Ottawa Golf Club completed seven rounds (126 holes) in one day, starting at 3:45 a.m., finishing at 7:30 p.m. His average score was 97, and he covered about 32 miles on a very hot day.

English point-to-point matches

In 1898, two English golfers successfully golfed a 35-mile cross-country hole from Maidstone to Littlestone-on-Sea. A wager of five pounds was placed that it couldn’t be done in less than 2,000 strokes. T. H. Oyler and A.G. Oyler took up the wager and a student at Cambridge served as the umpire to keep score, “although if he knew the large amount of monotonous work attached to it, it is very doubtful if he would have accepted it.”

The golfers took clubs with them along with about a half-gallon of balls that were newly painted, carried in a bag. Progress in the morning across fields was slow with hazards of hedges and ditches. After lunch, they played the road rather than across fields. But the balls tended to roll into the ditches on the side of the road, so they returned to the fields and woods.

They stopped for the night and were back at it the next day. While on a farm, the owner demanded to know what they were doing on his land. “We’re playing golf.” He replied, “I just request you to leave as quickly as possible.” Difficulties include strong winds and a high fence that took five strokes to get over. On the third day, one of the golfers explained, “Twice our ball hit a sheep and we were frequently in small ditches, but could generally play out.”

The challenge was accomplished in 1,087 strokes, 17 lost balls, and 72 penalty strokes. One critic stated, “Such feats as these are spectacular and attract attention for the moment, but will not become popular, because of the great powers of endurance necessary to carry out such stunts. I do not imagine a long jaunt over mountainous hills and dales, with many natural traps, would appeal to very many.”

The challenge was accomplished in 1,087 strokes, 17 lost balls, and 72 penalty strokes. One critic stated, “Such feats as these are spectacular and attract attention for the moment, but will not become popular, because of the great powers of endurance necessary to carry out such stunts. I do not imagine a long jaunt over mountainous hills and dales, with many natural traps, would appeal to very many.”

In 1920, a shorter 20-mile hole was played over rivers, swamps and hills near Cardiff between D. Rupert Lewis and W. Raymond Thomas. They played alternate stroke, were chased by a bull, and accomplished the hole with 608 strokes in 16 hours, losing 20 balls

Early Scottish world records

The endurance swinging and walking continued in 1908, when two well-known golfers from Edinburgh Scotland, Gray and Ferrier, played eight rounds, 144 holes, for about 40 miles, at Barnton. They started at 4 a.m. and finished their last round about 18 hours later, aided by the long summer daylight.

The endurance swinging and walking continued in 1908, when two well-known golfers from Edinburgh Scotland, Gray and Ferrier, played eight rounds, 144 holes, for about 40 miles, at Barnton. They started at 4 a.m. and finished their last round about 18 hours later, aided by the long summer daylight.

Also, in 1908 Harry B. Lumsden, a golfer from Aberdeen, Scotland, played the Balgonie Links nine times in a day, 162 holes for about 45 miles, setting a world record. He golfed for 15 hours with an average score per round of 82. A critic commented, “It is not easy to extract any useful lesson from the feats of endurance that are occasionally chronicled in connection with golf matches.” Soon after that another golfer from Scotland increased the world record to 192 holes for about 42 miles in 17 hours.

In June 1910, Lumsden was at it again in Aberdeen and accomplished an impressive 12 rounds, 216 holes, covering about 50 miles, and average 82.5 strokes per round. That world record would last for the next 13 years. Using the long summer light, he started at 2:20 a.m. and finished at 9 p.m. His fifth round was his best with a score of 77. “The excellence of the scoring is perhaps the most remarkable thing about this feat.”

In 1911, a Detroit newspaper commented on the marathon golf accomplishments that had taken place in Scotland, “The mere recital of them makes one feel tired. Besides, it is not golf, this sort of thing. It may be noted that these extraordinary fats of endurance took place some years ago and one may conclude that they happened before the rubber-cored ball came to stretch out all our courses to the utmost, for there can be no doubt at all that a round of average course today is a more strenuous affair than it used to be. As a mere feat of pedestrianism two rounds a day is as much as most of us care to tackle.”

In 1911, a Detroit newspaper commented on the marathon golf accomplishments that had taken place in Scotland, “The mere recital of them makes one feel tired. Besides, it is not golf, this sort of thing. It may be noted that these extraordinary fats of endurance took place some years ago and one may conclude that they happened before the rubber-cored ball came to stretch out all our courses to the utmost, for there can be no doubt at all that a round of average course today is a more strenuous affair than it used to be. As a mere feat of pedestrianism two rounds a day is as much as most of us care to tackle.”

First American marathon golfers

Americans also got into the “sport” early. In 1900, George McGrew, age 54, played 72 holes at the fair grounds in St. Louis, Missouri. “As far as can be figured, no one ever played as many as 72 holes hereabouts. Such play means walking fourteen miles in no less than ten hours.”

On June 2, 1906, J. S. Judd and E. O Smith of Springfield, Massachusetts, played six rounds, 108 holes for an estimated walking distance of 27 miles, the first known Americans to golf “ultra-distance.” They started early in the morning and finished late into the evening.

George Lytton and Andrew McCaughey – 153 holes

Around 1910, George Lytton, an amateur boxer, and Andrew McCaughey, a football player and oarsman, wanted to compete in a sport against each other. They chose to use the neutral sport of golf to see who could last the longest. They knew nothing about previous marathon golfing. They played at the Exmoor Country Club in Highland Park, Illinois, starting at 4:30 a.m. Both carried their own clubs throughout the day.

The two played three rounds before breakfast and decided to continue throughout the entire day and set some sort of new record. Their pace was playing nine holes every 45 minutes. They walked and did not run. “At noon both were still going strong and they stopped a half hour for lunch. During the afternoon there were many other players on the course, but word went around that George and Mac had all records distanced and players invariably gave them the right of way.”

They continued to play on, despite blistered feet, and finished at 7:45 p.m. with 153 holes, 8.5 rounds, traveling about 42 miles. McCaughey lost ten pounds during the day and had fewer strokes. But Lytton claimed that he walked the farthest.

Crazy golf match planned

In 1911, a truly crazy golf match was planned by members of the Park Ridge Country Club near Chicago. The distance was only 15 miles, but worthy of mention because he was so odd. “Twenty-four members of the club will gird up their loins and play golf through the city all the way to Lincoln Park, fifteen miles. According to the rules as received, all houses, barns, street cars, pedestrians, motorists, rivers or lakes will be the natural hazards of the trip. The match starts at six in the morning, just in time for the merry commuter to have the occasional stray golf ball drop in for breakfast.” It turned out to be a practical joke article that fooled many newspapers on the east coast.

In 1911, a truly crazy golf match was planned by members of the Park Ridge Country Club near Chicago. The distance was only 15 miles, but worthy of mention because he was so odd. “Twenty-four members of the club will gird up their loins and play golf through the city all the way to Lincoln Park, fifteen miles. According to the rules as received, all houses, barns, street cars, pedestrians, motorists, rivers or lakes will be the natural hazards of the trip. The match starts at six in the morning, just in time for the merry commuter to have the occasional stray golf ball drop in for breakfast.” It turned out to be a practical joke article that fooled many newspapers on the east coast.

Many reporters of the time could not embrace marathon golf. “Freak golf usually is the result of a new player being caught up in the chariot of fire of his enthusiasm or the result of a bet. Street golf, marathon golf, blindfolded golf, golf played in suits of armor, are some expressions of these vagaries. The trouble with a man who plays 100 holes or more in one day is that he does not get enough practice. His scores show that.”

Women join the sport

Even though women were excluded from playing in many country clubs, some embraced marathon golfing. On September 10, 1912, Corralla Lukens and Theris Hogan finished 81 holes (about 22.5 miles) at the Edgewater Golf Club in Chicago. The young women started at 6 a.m. and finished at 7 p.m. “They managed to press two unsuspecting caddies into their service. At noon the two tired and disgusted boys threw up the job and two others had to be offered excessive bribes to take their place.” It wouldn’t be until 1931 that a woman went into ultra-distance territory. That year, Mrs. F. C. Yates of Omaha, Nebraska played 111 holes in a day in Buenos Aires, Argentina for about 28 miles.

Even though women were excluded from playing in many country clubs, some embraced marathon golfing. On September 10, 1912, Corralla Lukens and Theris Hogan finished 81 holes (about 22.5 miles) at the Edgewater Golf Club in Chicago. The young women started at 6 a.m. and finished at 7 p.m. “They managed to press two unsuspecting caddies into their service. At noon the two tired and disgusted boys threw up the job and two others had to be offered excessive bribes to take their place.” It wouldn’t be until 1931 that a woman went into ultra-distance territory. That year, Mrs. F. C. Yates of Omaha, Nebraska played 111 holes in a day in Buenos Aires, Argentina for about 28 miles.

Fred Knight – 144 holes

During the World War I years, golfers took a break from marathon golfing. After the war, the “sport” really started to get attention due to the efforts by a golfer in Pennsylvania. In 1919, Frederick W. Knight (1887-1946) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, one of the best golfers of the city, sought to set what he thought would be a record of 126 holes. The actual record was still 216 holes set by Lumsden in 1910.

Knight was focused on completing the seven rounds with an average of 85 strokes or less per round. He started play on April 14, 1919 at 6:15 a.m. at the Whitemarsh Valley Country Club course in Lafayette Hill Pennsylvania. There was frost all over the course and once melted it was soaked with water.

Knight’s first round took him 1:45 and he scored an 87. By the end of four rounds he was four strokes off the 85 average. On his 7th round, “a gang of workmen passed him on the third hole. His ball lay short of the green with Wisshickon Creek between him and the green. Instead of waiting for him to make the shot, they walked on and as they passed, one of them remarked, ‘Watch him put it in the creek,’ and that is just what he did. Then to make matters worse, he hashed up the next shot and he registered an 8 on that hole.” After he finished his goal of seven rounds, he walked to the first tee and announced his intention of making an eighth journey.

Knight finished with an elapsed time of 14 hours 45 minutes, and actual playing time of 12:20. In the end he had played eight rounds, 144 holes, traveling about 40 miles, with 689 strokes. He missed his goal of averaging a score of 85 by only nine strokes. During his few breaks he would drink a glass of milk with a raw egg.

“It was hardly thought possible for a man to play seven rounds of golf at Whitemarch under the most favorable conditions, and yet Knight made eight trips over the course and played more golf in a single day than has ever been played in America by one man.” While his accomplishment wasn’t actually an American record (the record was 153 holes), it brought great attention to “marathon golfing” in many newspapers across America and soon Knight was incorrectly credited as being the originator of the sport of “marathon golf.”

“It was hardly thought possible for a man to play seven rounds of golf at Whitemarch under the most favorable conditions, and yet Knight made eight trips over the course and played more golf in a single day than has ever been played in America by one man.” While his accomplishment wasn’t actually an American record (the record was 153 holes), it brought great attention to “marathon golfing” in many newspapers across America and soon Knight was incorrectly credited as being the originator of the sport of “marathon golf.”

With all the attention Knight’s accomplishment caused, others quickly tried to beat Knight. Accomplishing eight rounds (144 holes) became common. One golfer kept track of all his expenses including greens fees during his 8 rounds and it came to 30 cents a mile or a total of $12, which was worth $183 in 2019 value.

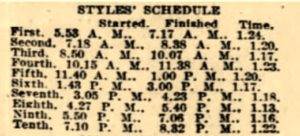

Edward Styles – 180 holes

On July 11, 1919, Edward Styles, age 48, of Philadelphia, of the Old York Road Country club, broke the true American record by completing ten rounds, 180 holes, covering about 50 miles, in 796 strokes, with an average of 79.6 strokes per round. His goal was to best Knight and do eight rounds in better than an 85 stroke average, but once he accomplished that, he continued on. He started at 5:53 a.m. and finished at 8:32 for an elapsed time of 14 hours 39 minutes.

Styles talked about his amazing day. “I could never have played that many holes if I had not been right down the alley all the time off the tee and on my brassie (2-wood) shots, nor could I have averaged under 80 for ten rounds if I had been in trouble all the time.

“Unlike Knight, who used a long swinging stride, Styles’ pace was more of the ‘heel and toe’ style, his steps short, but rapid. So fast did he get over the ground that many in the gallery were almost forced to trot to stay with him.”

“Unlike Knight, who used a long swinging stride, Styles’ pace was more of the ‘heel and toe’ style, his steps short, but rapid. So fast did he get over the ground that many in the gallery were almost forced to trot to stay with him.”

Others wanted to join in on the sport. Styles gave this advice, “Walking forty miles or more and hitting something like 800 golf shots of every kind takes a lot of strength and endurance. A player has to be in pretty good shape to try it.”

Others wanted to join in on the sport. Styles gave this advice, “Walking forty miles or more and hitting something like 800 golf shots of every kind takes a lot of strength and endurance. A player has to be in pretty good shape to try it.”

A Philadelphia golf champion who wasn’t a fan of marathon golf stated that after both Styles and Knight finished their marathon accomplishments, that neither regained their consistent golf talent again in normal competition.

Charles Daniels – 226 holes

Marathon golfers started to figure out how to golf many more holes in their quest for the record – do it on very short courses. In 1920, newspapers mentioned that Charles Daniels, a golfer from New York golfer had accomplished 226 holes using a very short 2100-yard, nine-hole golf course at Long Lake, New York. He traveled only about 38 miles, with an elapsed time of 16 hours. I don’t consider this a legitimate effort to qualify for a record.

Oscar B. Clow – 198 holes

On June 23, 1920, the true American record was broken again. Oscar “Ironman” B. Clow (1884-1942) of Tacoma, Washington, a “former marathon runner,” played 11 rounds, 198 holes, of the Meadow Park Golf Course in Tacoma Washington. He started at 4 a.m. and played continuously until noon, accomplishing seven rounds. A doctor then examined him and stated that his respiration was fine. Clow continued on until he finished his 11th round at 5 p.m. He traveled about 55 miles in 13 hours and used 1,085 strokes for a 98.6 stroke average for the rounds.

Clow’s caddy, Earl Williams accompanied him on a bicycle. His only duty was to watch the ball. “The caddy, although cutting corners and taking short cuts at every opportunity, was completely exhausted at the finish. Clow carried his own bag the entire way and lifted all the flags. He hit only one ball out of bounds and didn’t lose any balls.”

Arthur E. Velguth – 198 holes

On August, 22, 1922, Arthur Erich Velguth (1877-1944) of Spokane, Washington tied the American record playing 198 holes on the short nine-hole Spokane Down River Golf Course in Washington. It was thought at the time that he set a new world record, not knowing about Clow’s 1920 American accomplishment, nor Lumsden’s 1910 world record of 216.

Velguth took 1,069 strokes and covered about 44 miles in 15 hours. His breakfast consisted of four raw eggs and a half a pint of cream. He didn’t eat again until after he finished. His caddy, Tommy Willard made sure they walked all available short cuts. Velguth wanted Willard’s caddy services again, but the boy said, “Nothin’ doin’, I’m not a race horse.” Velguth confessed that he smoked 15-18 cigars daily. Some in the press mocked this silly record. One stated that Lulu Cargill’s mail-sorting record was much more impressive when she sorted 30,225 letters in eight hours.

Velguth took 1,069 strokes and covered about 44 miles in 15 hours. His breakfast consisted of four raw eggs and a half a pint of cream. He didn’t eat again until after he finished. His caddy, Tommy Willard made sure they walked all available short cuts. Velguth wanted Willard’s caddy services again, but the boy said, “Nothin’ doin’, I’m not a race horse.” Velguth confessed that he smoked 15-18 cigars daily. Some in the press mocked this silly record. One stated that Lulu Cargill’s mail-sorting record was much more impressive when she sorted 30,225 letters in eight hours.

Two months later, after hundreds of stories praising Velguth all over the country, Clow came forward and let everyone know that he also had accomplished 198 holes two years earlier on a course that was 1,000 yards further for 18 holes. Clow still held the American record.

Dan Kenny and William Lundberg – 216 holes – tied world record

In 1923, a golf marathon craze exploded all over America much like the 50-mile frenzy of 1963 when everyone wanted to hike 50 miles. In 1923, a golfer or two at most country clubs across the nation set their sights on showing what they could do golfing over and over again on their favorite course.

Two golf professionals from the Houston, Texas area made their attempt at a record on June 8, 1923 at the Glenbrooke Country Club. They ended up matching Lumsden’s world record of 216 holes on a nine-hole, 3,000 yard, hilly course. They started at 4:30 a.m. with the first hole lit up by automobile headlights and ended at 8 p.m. using flashlights.

During that day it reached 116 degrees. Their elapsed time was 15:30. It was explained that with two players , It takes longer than a single player because the players stop and wait for the other to hit. Kenny played the holes in a very impressive 957 strokes for an 18-hole round average of 79.75. Lundberg used 1,003 strokes.

“At the close of play both golfers stated that they could continue for at least two more rounds. Aside from blistered feet, no ill-effects were felt. Play was continuous throughout the day, the golfers being fed as they played. The only delays came when it was necessary to change shoes. The golfers carried only four clubs each. Caddies worked in relays and were used in locating tee shots.”

“At the close of play both golfers stated that they could continue for at least two more rounds. Aside from blistered feet, no ill-effects were felt. Play was continuous throughout the day, the golfers being fed as they played. The only delays came when it was necessary to change shoes. The golfers carried only four clubs each. Caddies worked in relays and were used in locating tee shots.”

Nick J. Morris – 238 holes – world record

On June 22, 1923, Nick “JD” Morris, a 21-year-old amateur golfer from San Antonio, Texas, set a new world record of 238 holes, 13 rounds plus four more holes, covering about 60 miles on the 6,200 yard Brackenridge Municipal 18-hole course. He started at 4:55 a.m. and finished at 8:10 p.m. for an elapsed time of 15:15.

On June 22, 1923, Nick “JD” Morris, a 21-year-old amateur golfer from San Antonio, Texas, set a new world record of 238 holes, 13 rounds plus four more holes, covering about 60 miles on the 6,200 yard Brackenridge Municipal 18-hole course. He started at 4:55 a.m. and finished at 8:10 p.m. for an elapsed time of 15:15.

Morris used only four clubs, “a driver, midiron, mashie (wedge), and putter. From start to finish he astonished the field of 3,000 who followed his play by his long, straight drives.” Throughout the day he fed on a dozen oranges, a bottle of dry malted milk, and two ounces of raisins. Morris made a rookie ultrarunner mistake. He said, “If I had not worn high shoes in the morning rounds, I am sure my foot would not be hurting me now. I had them laced too tight.”

Morris averaged a bit more than 89 strokes for his rounds. “After he had finished the 12th round, he was forced to play the first nine holes twice for the 13th round. The greens were being watered on the last nine, making it impossible to putt. The fist nine measure some 200 yards father than the last nine.” After finishing his 13th round, he played the first two holes twice before darkness forced him to stop.

Rudolph C. Supan – 257 holes – world record

The 1923 marathon golf craze continued. On July 6, 1923, Rudolph Supan (1902-1963), a 21-year old originally from Czechoslovakia, and a veteran of World War I, started at 4:20 a.m. on the Highland Park nine-hole golf course near Cleveland, Ohio. He finished 257 holes for a new world record, completing 14+ rounds, covering about 65 miles before darkness. His elapsed time was 16.5 hours.

The 1923 marathon golf craze continued. On July 6, 1923, Rudolph Supan (1902-1963), a 21-year old originally from Czechoslovakia, and a veteran of World War I, started at 4:20 a.m. on the Highland Park nine-hole golf course near Cleveland, Ohio. He finished 257 holes for a new world record, completing 14+ rounds, covering about 65 miles before darkness. His elapsed time was 16.5 hours.

During his rounds, he only took one eight-minute rest, tired out eight caddies, and wore out two pair of shoes. He played through two rainstorms. Supan ran between shots, the first known marathon golfer known to truly try to run it. Spectators tried to keep up but soon gave up. After 10 hours he slowed down to a fast walk.

The 1923 marathon golf frenzy continues

A day later, Herbert Oberdorf, a professional golfer at High Point Country Club in North Carolina thought he broke the world record when he played 243 holes in twelve hours, forty three minutes. He likely did have the record for the most holes up to that point in 12 hours. His “elation over his feat was short lived” when he learned that his hole total was bested the day before by Supan.

Ten days later, two golfers, William McGuire, and Eddie Tipton of Washington D.C. went for the glory on the East Potomac Park course. They ran between shots, used 15 caddies, ten scorers, eating only oranges but came up short of Supan’s record, reaching 216 holes. The two wore pedometers. McGuire’s registered 69 miles for his 1,007 strokes and Tipton’s registered 57 miles for his 1,084 strokes. Both lost seven pounds during the day and Tipton played the final 18 holes in his stocking feet because of a bad blister on his right heel.

During this 1923 marathon golf craze, most traditional golfers turned their noses up to the fad. Charlie Betschler of the Park Heights Avenue course in Baltimore, Maryland said, “It’s not an endurance test, but a speed test. There is only a certain number of playing hours each day, and the one who can go the fastest will win, and that’s not golf.”

Nick J. Morris – 290 holes – world record

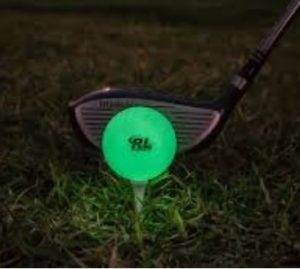

Nick J. Morris, age 21, of San Antonio wanted the world record back that he had set and lost in just a month. He set out on July 27, 1923 at 12:40 a.m. in bright moonlight, using an “illuminated ball” and many specially trained ball hunting caddies. He hoped to reach 300 holes before sundown. “Although the gallery was small at the early morning start, there is no doubt that traffic cops will be necessary before the feat is completed and arrangements have been made for Morris to have right of way over all players.”

Nick J. Morris, age 21, of San Antonio wanted the world record back that he had set and lost in just a month. He set out on July 27, 1923 at 12:40 a.m. in bright moonlight, using an “illuminated ball” and many specially trained ball hunting caddies. He hoped to reach 300 holes before sundown. “Although the gallery was small at the early morning start, there is no doubt that traffic cops will be necessary before the feat is completed and arrangements have been made for Morris to have right of way over all players.”

Morris reclaimed the world record, finishing 290 holes in 19:10 for about 72 miles. He averaged shooting 85 strokes per round. His tenth round was his best with a score of 80. Morris, a clerk at a drug company, did have difficulty with an injured knee which he nursed after the 15th round and cramped up during some swings. “He said he was through with marathon golf and does not care to compete against anyone who may surpass his record.”

The craze fades out

The 1923 marathon golf craze ran its course, especially with the untouchable record that Morris posted. Some continued to do it, including a 62-year-old Hiram Ramp who played 144 holes. A journalist wrote, “Golf is too good a game to take in such huge doses and if all sixty-year-old golfers get the craze some of them are sure to suffer and then the grand old game will be blamed.”

This definition of marathon golf was published across the country: “The idea, if any, in this game is to see how many different varieties of sap you can make of yourself between sun up and sun down. It is one of the things that makes you realize the utter futility of daylight saving.”

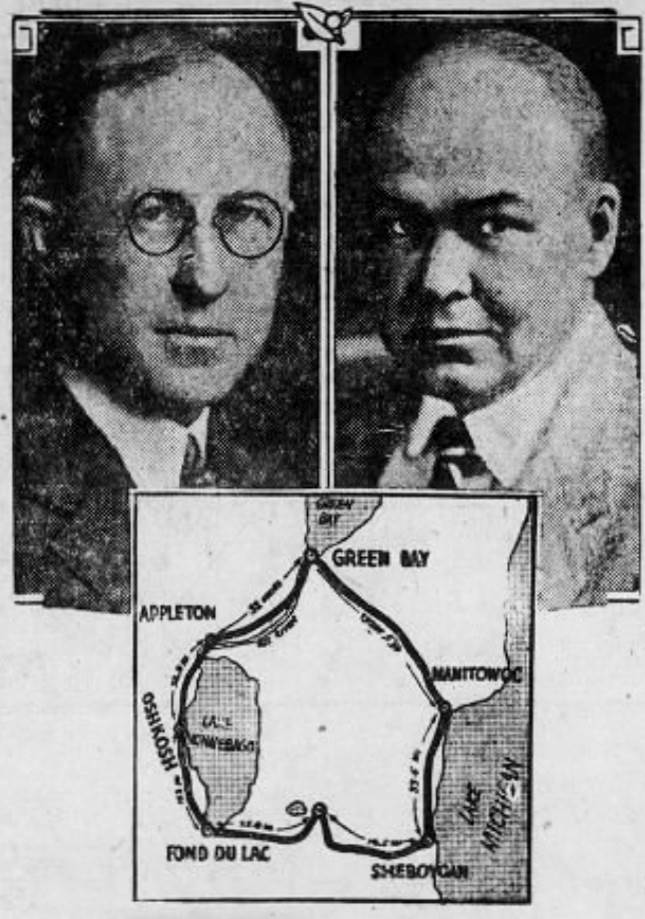

A new twist was performed in Wisconsin on August 2, 1924 when local golf stars, J. D. Steele, and H. L Davis played seven nine-hold rounds on seven courses in seven different cities in 16 hours. They traveled 230 miles during that time. Each round averaged 1:10. In a similar attempt a golfer used an airplane to shuttle him between courses, but he ended up with bad motion sickness.

A new twist was performed in Wisconsin on August 2, 1924 when local golf stars, J. D. Steele, and H. L Davis played seven nine-hold rounds on seven courses in seven different cities in 16 hours. They traveled 230 miles during that time. Each round averaged 1:10. In a similar attempt a golfer used an airplane to shuttle him between courses, but he ended up with bad motion sickness.

Golf attempt from Alabama to California

By 1927, the newspapers had forgotten about the best marathon golf performances and nearly every accomplishment was called a record. That year, Doe Grahame attempted driving a golf ball from Mobile, Alabama to Los Angeles, California. On February 13th, about 100 people braved heavy rain to watch Grahame start, along with his 18-year-old caddy, Happy Kirby. “Mathematical calculations indicate it would require 123,200 strokes over a journey of estimated at 3,500 miles.” Grahame estimated it would take him between five months and five years and that he would take 1.5 million strokes.

By 1927, the newspapers had forgotten about the best marathon golf performances and nearly every accomplishment was called a record. That year, Doe Grahame attempted driving a golf ball from Mobile, Alabama to Los Angeles, California. On February 13th, about 100 people braved heavy rain to watch Grahame start, along with his 18-year-old caddy, Happy Kirby. “Mathematical calculations indicate it would require 123,200 strokes over a journey of estimated at 3,500 miles.” Grahame estimated it would take him between five months and five years and that he would take 1.5 million strokes.

The rain was terrible on the first day and they had to take shelter after four miles. But by the second day Grahame had made 40 miles. “The first night out, he and his caddy slept in a farmer’s stable. On Monday he was lost and when he regained the right road, Kirby slipped down an embankment and had to have medical attention. That night a church was their refuge.” Each time he took a ferry across a river, it cost him a stroke.

The rain was terrible on the first day and they had to take shelter after four miles. But by the second day Grahame had made 40 miles. “The first night out, he and his caddy slept in a farmer’s stable. On Monday he was lost and when he regained the right road, Kirby slipped down an embankment and had to have medical attention. That night a church was their refuge.” Each time he took a ferry across a river, it cost him a stroke.

He spent one night in jail when a sheriff caught him acting suspiciously with a flashlight and golf clubs late at night. He used a driver through the countryside, a two-wood in the suburbs, and putted along city sidewalks. By March 26rd, he was playing through Houston Texas and had 21,643 strokes on his card with 73 lost balls. He had golfed for about 43 days and covered more than 500 miles.

At San Antonio, Texas, his caddy had to return home to Mobile, so Grahame was on his own. Leaving San Antonio, he lost track of his strokes so had go back to start again from the city. He had taken 31,237 strokes. The lost ball count was up to 114.

Grahame made it to Ozona, Texas before quitting on April 22,1927 after more than two months, because he ran out of funds. Up to that point he had 35,948 strokes, lost 140 golf balls, and lost 25 pounds. He had golfed for more than 900 miles.

Golfing for more than six days

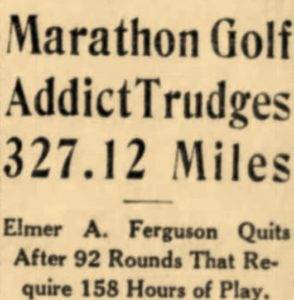

In 1930, Elmer A. Ferguson of the American School of Theater Arts played golf for nearly an entire week. He walked about 350 miles, completing 828 holes with 3,999 strokes on a nine-hole golf course at Ridgemont in Detroit. He had one hole in one along the way. At night he was helped by a barn lantern and a pocket flashlight. His caddie held the lantern on the green as he drove on a short hole or between the tee and green on longer holes. The ball was covered with luminous paint.

In 1930, Elmer A. Ferguson of the American School of Theater Arts played golf for nearly an entire week. He walked about 350 miles, completing 828 holes with 3,999 strokes on a nine-hole golf course at Ridgemont in Detroit. He had one hole in one along the way. At night he was helped by a barn lantern and a pocket flashlight. His caddie held the lantern on the green as he drove on a short hole or between the tee and green on longer holes. The ball was covered with luminous paint.

Ferguson said of his followers, “The gallery ran from about 25 in the wee hours to mobs in the daytime. In the early morning hours, I would have a lot of golf professionals and newspaper men in the gallery waiting to see me go to sleep, but they were disappointed. He played pretty much non-stop for 158 hours and gave up due to badly swollen hands.

Other Depression era marathon golf fads

In 1930, more variations appeared. J. Lathrope of Princeton, New Jersey kicked off “speed golfing” by playing the 6,186-yard Springdale course in only 50 minutes, scoring an 88. He sprinted between shots and used two caddies.

In 1930, more variations appeared. J. Lathrope of Princeton, New Jersey kicked off “speed golfing” by playing the 6,186-yard Springdale course in only 50 minutes, scoring an 88. He sprinted between shots and used two caddies.

Also in 1930, marathon miniature golf was established at the Colony miniature golf course in Chicago. Sixteen young men and women, under the direction of M. L. Mathleu, owner and manager, started the contest that was broadcast nightly on the radio. The objective was to golf until you dropped. The winner golfed for 136 hours.

This event was soon copied in Montreal, Canada with 37 contestants. The winner played for 100 hours. “The players batted the ball around continuously, munching sandwiches and chewing oranges as they went, stroking day and night through water pipes, over dish pans and up little hills and down little valleys with tireless monotony.” It was estimated that 4,000 rounds were played by al the contestants and that they were watched by 7,000 spectators.

Robert Coy – Marathon golf fraud?

Records could have been cheated. In the early 1900s, many ultrarunners fabricated transcontinental accomplishments (see Dakota Bob) and other claims. These individuals were commonly self-promoters who accomplished stunts, and sought records for attention and financial gain. During the Great Depression, many of these solo endurance performers emerged in a desperate effort to earn money.

It appears that such was the case with at least one individual who came onto the stage in 1931, establishing spectacular marathon golf records. He was not known to be a great golfer. Each time he broke the world record, the details about the effort were very scarce. News coverage on the day of the attempt was always non-existent. This individual was Robert Norman “Chief” Coy.

Robert Norman Coy (1902-1980) was from Peoria, Illinois and was born in 1902. He only finished the 8th grade. He was a former welter-weight boxer that went by the name of Chief Coy because he said he could whip every boy in grade school. It was said that he had an awesome face, the right side was paralyzed, not from fighting but from childhood when his father struck him. “His great slanting face became his trademark as a fighter.”

Robert Norman Coy (1902-1980) was from Peoria, Illinois and was born in 1902. He only finished the 8th grade. He was a former welter-weight boxer that went by the name of Chief Coy because he said he could whip every boy in grade school. It was said that he had an awesome face, the right side was paralyzed, not from fighting but from childhood when his father struck him. “His great slanting face became his trademark as a fighter.”

In 1927 he was in the news when he attempted a “nonstop” 130-mile run from Peoria to Bloomington, Indiana and back and then planned to run 35 miles on a track in front of spectators. His run was a failure when he gave up his running stunt at mile 22 because of thick mud. In 1929 he returned to the boxing ring.

In late 1929 Coy sprang onto the endurance scene with many claims. The Chicago Tribune thought one of his letters to try to get a fighting bout was amusing. They mocked his letterhead of “modesty” where he proclaimed that he was a “fighter, wrestler, strong man, runner, the super athlete of the age.” The news reporter was skeptical. Coy stated, “I hold the world’s record for playing the most holes in one day, 234. I hold all the marathon running records in Central Illinois.” These kinds of claims were a huge red flag for typical endurance frauds of the time.

In late 1929 Coy sprang onto the endurance scene with many claims. The Chicago Tribune thought one of his letters to try to get a fighting bout was amusing. They mocked his letterhead of “modesty” where he proclaimed that he was a “fighter, wrestler, strong man, runner, the super athlete of the age.” The news reporter was skeptical. Coy stated, “I hold the world’s record for playing the most holes in one day, 234. I hold all the marathon running records in Central Illinois.” These kinds of claims were a huge red flag for typical endurance frauds of the time.

In 1930 Coy played pocket billiards for 120 hours without stopping, a world record. “As the week wore on, crowds came and went. After a couple days Coy started mistaking the nine ball of the cue ball. After 120 hours, it was over. He staggered backwards and began babbling deliriously. A crowd spilled out into the street cheering, spreading the news that Chief Coy and done the impossible.”

Later in 1930 because of the billiards record claim, he was invited to participate in the world championship of pocket billiards. “All that is known about him is that he holds the world marathon record for pocket billiard playing.” Coy announced that he was going to walk from Peoria to New York City for the contest. Nothing was heard of him, he just didn’t show up.

Later in 1930 because of the billiards record claim, he was invited to participate in the world championship of pocket billiards. “All that is known about him is that he holds the world marathon record for pocket billiard playing.” Coy announced that he was going to walk from Peoria to New York City for the contest. Nothing was heard of him, he just didn’t show up.

Learning that the world record for marathon golf was actually 290 holes, Coy wanted to break it. On June 18, 1931 with sparse details, he claimed to play the Monmouth Country club nine-hole course in Illinois, playing 302 holes, covering at least 70 miles on the 6,400 yard course in 16 hours, 20 minutes. He claimed that he did it in bare feet and used only one club, a mid-iron. A news story published later stated, “Outside of a blistered hand and a bad case of sunburn, he suffered no ill effects. To prove it, on finishing the 302nd hole, he ran a hundred yards in less than 11 seconds. Then he put on a strength demonstration bending a steel bar with his teeth, tearing a tobacco can in half and driving a 20-penny spike through an inch board with his bare hands.”

Learning that the world record for marathon golf was actually 290 holes, Coy wanted to break it. On June 18, 1931 with sparse details, he claimed to play the Monmouth Country club nine-hole course in Illinois, playing 302 holes, covering at least 70 miles on the 6,400 yard course in 16 hours, 20 minutes. He claimed that he did it in bare feet and used only one club, a mid-iron. A news story published later stated, “Outside of a blistered hand and a bad case of sunburn, he suffered no ill effects. To prove it, on finishing the 302nd hole, he ran a hundred yards in less than 11 seconds. Then he put on a strength demonstration bending a steel bar with his teeth, tearing a tobacco can in half and driving a 20-penny spike through an inch board with his bare hands.”

He also claimed that some of these nine-hole rounds were done in only 15 minutes, which was golfing at a six-minute mile pace during nine holes. His new 302 hole world record was likely a fraud but the public soaked it all in.

Bob Swanson – 305 holes – world record?

Bob Swanson, age 23, from Los Angeles, California, was another stunt artist who wished to beat Coy. In July 1933, he claimed to complete 305 holes of the Sunset Fields course at Los Angeles for about 76 miles. He stared around 2 a.m. and finished in 20 hours and 45 minutes. Earlier that year he claimed to have accomplished 200 holes in 17.5 hours. His 305 hole accomplishment was a dramatic improvement. Details of his 305 round accomplishment are lacking and newspaper coverage was sparse. One must be skeptical of his world record.

Coy claims 314 holes

It was then Coy’s turn to get the record back. He claimed that on Jun 20, 1934, he played the Patty Jewette course in Colorado Springs, for 24 hours, finishing 314 holes, covering about 80 miles. At 12 hours he had reached 127 miles which he claimed was a world record. The only other details given were, “Through the night he was accompanied by caddies armed with flashlights and many spectators.” Oddly, no news stories about the event originated from Colorado newspapers. This accomplishment was again likely fraudulent.

It was then Coy’s turn to get the record back. He claimed that on Jun 20, 1934, he played the Patty Jewette course in Colorado Springs, for 24 hours, finishing 314 holes, covering about 80 miles. At 12 hours he had reached 127 miles which he claimed was a world record. The only other details given were, “Through the night he was accompanied by caddies armed with flashlights and many spectators.” Oddly, no news stories about the event originated from Colorado newspapers. This accomplishment was again likely fraudulent.

Jim Ford – 335 holes – world record

Just two days later, Jim Ford, a youth from Portland, Oregon completed 335 holes in 24 hours and claimed the world record, covering about 85 miles. “He finished in good physical condition but slightly sleepy. He required 1,632 strokes. The speedometer of an automobile which followed him over the Peninsula Country club course registered 78 miles.” Surely Coy was bothered that his “record” had so quickly been snatched away.

Just two days later, Jim Ford, a youth from Portland, Oregon completed 335 holes in 24 hours and claimed the world record, covering about 85 miles. “He finished in good physical condition but slightly sleepy. He required 1,632 strokes. The speedometer of an automobile which followed him over the Peninsula Country club course registered 78 miles.” Surely Coy was bothered that his “record” had so quickly been snatched away.

Swanson reaches 343 holes on short course

Just five days later, Swanson started his quest to get the record back and he became smart. He chose a very short, flat, nine-hole course (less than 2,400 yards) at Nibley Park in Salt Lake City, Utah, using only a three-iron. Swanson started at midnight, took several rests because of the altitude, and still finished 343 holes in 23 hours, 30 minutes. “His performance was attested by two Nibley caddies, Roy Lambert and Max Wilkinson.” He was really hoping for 400 holes on the short course. He lost 14 balls during the night.

Just five days later, Swanson started his quest to get the record back and he became smart. He chose a very short, flat, nine-hole course (less than 2,400 yards) at Nibley Park in Salt Lake City, Utah, using only a three-iron. Swanson started at midnight, took several rests because of the altitude, and still finished 343 holes in 23 hours, 30 minutes. “His performance was attested by two Nibley caddies, Roy Lambert and Max Wilkinson.” He was really hoping for 400 holes on the short course. He lost 14 balls during the night.

It was reported, “While it was dark, he did not hit his ball very far and consequently scored higher. His caddy carried a huge flashlight and the streetlights adjacent to several of the holes helped out considerably.”

Given these details it appears Swanson’s accomplishment was legitimate. However, the short course must be disqualified for a true world record because he only actually covered about 60 miles. Ford still held the legitimate record with 335 holes.

Coy claims to reach 357 holes

On learning of Swanson’s 343 holes, within two weeks, Coy claimed that he played 357 holes in 24 hours at the short Madison Public Links (about 5,000 yards) in Peoria on July 7, 1934. His distance would have only been about 62 miles. It was said he started his attempt at 8:10 p.m., accompanied by six caddies bearing flashlights and was followed by a large gallery, the same general information published about his previous record journey. This record should not be believed and the course was too short.

On learning of Swanson’s 343 holes, within two weeks, Coy claimed that he played 357 holes in 24 hours at the short Madison Public Links (about 5,000 yards) in Peoria on July 7, 1934. His distance would have only been about 62 miles. It was said he started his attempt at 8:10 p.m., accompanied by six caddies bearing flashlights and was followed by a large gallery, the same general information published about his previous record journey. This record should not be believed and the course was too short.

Bill Farnham – 376 holes – very short course

The short course attempts continued. On August 12, 1934, at nine-hole Guilford Lakes course in Guilford, Connecticut, golf pro, Bill Farnham claimed to achieve 376 holes in 24 hours, 10 minutes. The nine-hole course was extremely short, only about 1,300 yards. Today it is only a par 27 course. For 18 holes, it was only 2,600 yards. Previous legitimate records were set on 18-hole courses of more the 6,000 yards. The course that he used was less than half the normal length. He only covered about 42 miles. This didn’t come close to qualifying for a comparable true world record.

The short course attempts continued. On August 12, 1934, at nine-hole Guilford Lakes course in Guilford, Connecticut, golf pro, Bill Farnham claimed to achieve 376 holes in 24 hours, 10 minutes. The nine-hole course was extremely short, only about 1,300 yards. Today it is only a par 27 course. For 18 holes, it was only 2,600 yards. Previous legitimate records were set on 18-hole courses of more the 6,000 yards. The course that he used was less than half the normal length. He only covered about 42 miles. This didn’t come close to qualifying for a comparable true world record.

Coy’s 1,000 hole attempt

In 1935, Coy probably knew he couldn’t beat Farnham’s 376 mark in front of witnesses, so he invented a way to better it. He invented the “continuous” golf record, golfing until you had to quit. He considered that Farnham’s 376 holes set the year before was that record. Coy wanted to reach 1,000 holes.

In 1935, Coy probably knew he couldn’t beat Farnham’s 376 mark in front of witnesses, so he invented a way to better it. He invented the “continuous” golf record, golfing until you had to quit. He considered that Farnham’s 376 holes set the year before was that record. Coy wanted to reach 1,000 holes.

“Continuous” records such as these have also plagued the sport of ultrarunning over the years. They were usually only pursued by stunt performers. The efforts were never continuous, and could have built-in rests. They were just invented records for the Guinness book of “world records.”

Conveniently, Coy wouldn’t be monitored closely, and would just have on e caddie along to carry a flashlight during the night. He planned to carry only one club, a two-iron. Starting on January 21, 1935, he played on the 6,500-yard Portrero Country Club in Los Angeles, California. True to his form, at the first tee he took a bar of iron and tied it into knots using his hands and his teeth. He also bent a half-inch bolt in a U shape.

Coy claimed to reach 300 holes during the first 24 hours. His main source of calories was ice cream with coffee. In the morning his caddie brought out to him eggs, bacon, a doughnut, and bread. Coy ate without stopping. His caddies worked in 3-4 hour shifts. “The boys who accompany him say he doesn’t talk about golf. He regales them with stories of his feats of strength.” When he hit the ball into the water, he made the boys fetch the ball out of the water. During the first night it took him seven shots to get out of a sand trap while his caddy stood there with a flashlight and watched him whale away

After 459 holes, Coy quit and was taken to the hospital with badly swollen ankles. A witness said that when he quit, he could scarcely swing the club. Coy estimated that he walked more than 100 miles during his 39 hours of play.

After 459 holes, Coy quit and was taken to the hospital with badly swollen ankles. A witness said that when he quit, he could scarcely swing the club. Coy estimated that he walked more than 100 miles during his 39 hours of play.

Coy returned to Peoria, Illinois and a few months later claimed that he played 1,000 holes of “continuous golf” at the short Madison course (5,000 yards) in 51 hours, 36 minutes. He said he only used one club all the way and that an ice cream firm sponsored him. He wore a sweat shirt advertising their product.

Coy returned to Peoria, Illinois and a few months later claimed that he played 1,000 holes of “continuous golf” at the short Madison course (5,000 yards) in 51 hours, 36 minutes. He said he only used one club all the way and that an ice cream firm sponsored him. He wore a sweat shirt advertising their product.

Coy said, “Then they set five-gallon cans of ice cream around the course. I didn’t stop to eat. I’d just dip in and get some ice cream and keep walking. I didn’t hit the ball hard at night, just topped it, and the caddies went ahead of me with flashlights. I could have played longer, but I figured that record would stand.”

Coy said, “Then they set five-gallon cans of ice cream around the course. I didn’t stop to eat. I’d just dip in and get some ice cream and keep walking. I didn’t hit the ball hard at night, just topped it, and the caddies went ahead of me with flashlights. I could have played longer, but I figured that record would stand.”

There was no local newspaper coverage found of the event. Coy was the only source of the news. He wrote to the Los Angeles Times and other papers. “I started June 3, 1935 and played straight through without a stop to June 5th.” Believe it or not?

What happened to Coy?

Coy retired from golf stunts but went on to other things including playing the piano for consecutive five days and nights in a store window. He got politicians to pay him to put their posters next to his piano. He claimed to hitch-hiked to every state capitols and getting the autographs of each governor. During World War II he served as a substitute mailman and jogged his route. He settled into an advertising career. He was hired to distribute advertising cards and bill around Peoria, Illinois. In 1952 it was written about him, “he fell in love with the idea of being a ‘world record’ holder no matter how obscure. He just liked the idea of having a new record and the publicity that sometimes came.”

In 1962 he wrote to the Chicago Tribune and said he could pack Comisky park to watch his stunts such as naming all the presidents of the United states in order or naming the first 50 popes. He also said he could walk 50 miles without pausing for a rest. In 1964 he was still seeking sponsors to do crazy things. In 1968 he asked that schools and banks close for his 66th birthday. Chief Coy died in 1980 at the age of 78.

In 1962 he wrote to the Chicago Tribune and said he could pack Comisky park to watch his stunts such as naming all the presidents of the United states in order or naming the first 50 popes. He also said he could walk 50 miles without pausing for a rest. In 1964 he was still seeking sponsors to do crazy things. In 1968 he asked that schools and banks close for his 66th birthday. Chief Coy died in 1980 at the age of 78.

Marathon golf into the modern era

During the next few decades after the 1930s, marathon golf attempts continued in isolated cases. There was no marathon golf published record book or even memories of records going forward. Many great accomplishments were made reaching well above 200 holes and in nearly all cases, world records were claimed. Some of these efforts were on very short courses. With better technology, fitness, lighting for courses, and true ultrarunners, the stage was set to break the records set in the 1930s.

Ian Colston – 401 holes – world record

On November 27, 1971, Ian Colston, a serious ultrarunner from Nanneela, Victoria, Australia, began his marathon golf attempt at 6 p.m. and finished at 5:15 p.m. the following day after playing 401 holes at the Bendigo Club’s course that was 6,061 yards. Colston covered about 95 miles. The club’s president and captain certified the accomplishment which shattered Jim Ford’s 1934 legitimate record of 335 holes.

Colston recalled many years later, “I was a pretty good runner back then and the Bendigo Golf Club approached me about trying to break the record, I remember covering 147 miles in a 24-hour period. I’d never been a serious golfer but I always enjoyed challenging myself. I trained extremely hard for six months and ran about 20 miles per day to make sure I was as fit as I could be. I had four motorbikes behind me all the time and I used a luminous golf ball.” The golf course installed lights for the record attempt. Colston continued, “As soon as I hit the ball one of the motorbike riders would take off to track the ball for me. I played smart and didn’t try and hit the ball too far. I kept it straight and tried to keep out of trouble.” Colston’s running career was cut short in 1974 when he was run over by a car when training for a run from Perth to Sydney.

Colston recalled many years later, “I was a pretty good runner back then and the Bendigo Golf Club approached me about trying to break the record, I remember covering 147 miles in a 24-hour period. I’d never been a serious golfer but I always enjoyed challenging myself. I trained extremely hard for six months and ran about 20 miles per day to make sure I was as fit as I could be. I had four motorbikes behind me all the time and I used a luminous golf ball.” The golf course installed lights for the record attempt. Colston continued, “As soon as I hit the ball one of the motorbike riders would take off to track the ball for me. I played smart and didn’t try and hit the ball too far. I kept it straight and tried to keep out of trouble.” Colston’s running career was cut short in 1974 when he was run over by a car when training for a run from Perth to Sydney.

In 1974, Mike Coon of Michigan claimed he broke Colston’s record with 407 holes in ten hours and tried to get that published in the Guinness Book of World Records, replacing Colston’s record. There was one big problem: Coon’s wife drove him around the course in a golf cart. What was he thinking?

Eric Byrnes – 420 holes – world record

On April 22, 2019, former Major League Baseball player, Eric Byrnes, age 43, played 420 hole in 24 hours at the Half Moon Bay Golf Links in California. The course was at least 6,000 yards. His strategy was taking many short, straight shots while still running. His method, while allowed, didn’t really involve golf shots. It was more like taking polo shots without a horse. Score didn’t really matter as it did to the marathon golf greats of the past.

On April 22, 2019, former Major League Baseball player, Eric Byrnes, age 43, played 420 hole in 24 hours at the Half Moon Bay Golf Links in California. The course was at least 6,000 yards. His strategy was taking many short, straight shots while still running. His method, while allowed, didn’t really involve golf shots. It was more like taking polo shots without a horse. Score didn’t really matter as it did to the marathon golf greats of the past.

He took a total of 3,538 strokes and his lowest round was 116. His highest was 168, so his batting arm strength came in handy for all those strokes. He covered about 106 miles and used just one club, a women’s 8-iron which he carried as he ran. A caddie friend ran with him and provided aid from carts that followed along the way.

Previously, in April 2018, Byrnes also broke Karl Melzer’s 2016 12-hour record, when Byrne achieved 245 holes. He played 13.5 rounds and ran a total of 65.5 miles at the Napa Valley Golf Club at Kennedy Park. Byrnes also had previously completed a trancontinental triathlon across America, swimming seven miles across the San Francisco Bay, biking over 2,400 miles from Oakland to Chicago, and running 905 miles from Chicago to New York City.

What is next for marathon golf? Perhaps, like ultrarunning, it will evolve into trail marathon golf using balls that have gps locators and emit sounds to be found easier.

Sources:

- Andrew Ward, Golf’s Strangest Rounds

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Jun 2, 1906

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Aug 11, 1909, Jul 24, 1911, Aug 20, 1911

- The Houston Post (Texas), Aug 14, 1910

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Aug 13, 1911, Sep 3, 1930

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Aug 24, 1912

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Aug 30, 1912, Jun 8, 22, Jul 7, 1923

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Sep 10, 1912

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Jan 2, 1913

- San Francisco Examiner (California), May 13, 1913

- The Honolulu Adviser (Hawaii), Apr 3, 1913, Jul 29, 1920, Aug 5, 1923

- Honolulu Star Bulletin (Hawaii), Jul 2, 1913, Jun 16, 1925

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Jul 26, 1913

- The Lincoln Star (Nebraska), Aug 22, 1913

- The Salina Daily Union (Kansas), Oct 8, 1913

- Oakland Tribune (California), Mar 28, 1915

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Apr 5, 15, Jul 12, 1919, Jun 21, 1923

- Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Apr 14-15, 1919, Feb 21, 1920

- The Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jan 21, 1900, Jun 21, 1918, Jan 1, 1930

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Jun 10, 1919, Jul 8 1920

- The Washington Times (Washington D.C.) Jan 5, Feb 4, 1920

- Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada), Jun 21, 1920

- The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), Jun 24, 1920

- New York Tribune, Dec 26, 1920

- The Semi-Weekly Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Aug 9, Oct 29, 1922

- Saskatoon Daily Star (Canada), Aug 22, Oct 21, 1922

- Wausau Daily Herald (Wisconsin), Aug 22, 1922

- Tucson Citizen (Arizona), Aug 22, 1922

- The Hutchinson Gazette (Kansas), Sep 27, 1922

- The Neosho Daily News (Missouri), Jun 8, 1923

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), Jun 22, 1923

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Jun 22, 1923

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Jun 25, 1923

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Jul 2, 1923

- The Coshocton Tribune (Ohio), Jul 8, 1923

- Los Angeles Times, Jul 7, 1923, Jun 12, 1935

- The Houston Post (Texas), Jul 8, 1923, Jan 22, 1935

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Jul 8, 1923

- Journal Gazette (Mattoon, Illinois), Jul 11, 1923

- The Evening News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Jul 16, 1923

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Jul 17, 1923

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Jul 17, 1923

- Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Jul 27, 1923

- Portsmouth Daily Times (Portsmouth, Ohio), Jul 27, 1923

- Austin American-Stateman (Texas), Jul 28, 1923, Apr 22, 1927

- The Richmond Item (Indiana), Apr 20, 1924

- The Dayton Herald (Ohio), Jul 16, 1924

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), Aug 3, 1924

- Wilmington News-Journal (Ohio), Jun 22, 1927

- Nebraska State Journal, Feb 14, 1927

- The York Daily Record (Pennsylvania), Feb 16, 1927

- Palladium-Item (Richmond, Indiana), Feb 19, 1927

- The Anniston Star (Alabama), Apr 9, 1927

- Suburbanite Economist (Chicago, Illinois), Jul 29, 1930

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Dec 13, 1930

- The Ottawa Citizen (Canada), Sep 3, 1931

- The Ithaca Journal (New York), Mar 18, 1932

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Jul 8, 1934

- The Butee Daily Post (Montana), Sept 12, 1932

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Jun 27, 1934

- Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), Jun 27, 1934

- Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Jun 23, 1934

- Jacksonville Daily Journal (Illinois), Sep 8, 1927

- Des Moines Tribune (Iowa), Apr 11, 1952

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Feb 5, 1980

- Bendigo Advertiser, “Colston reflect on amazing feat at golf course.”

- Golfweek, “How Eric Byrnes played 420 holes of golf in 24 hours”