Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 34:48 — 38.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

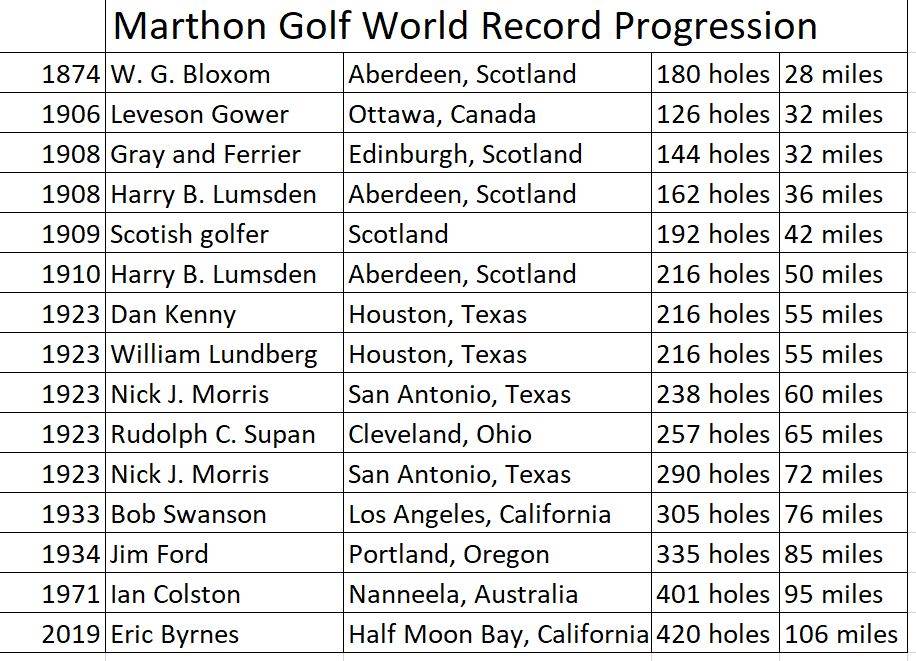

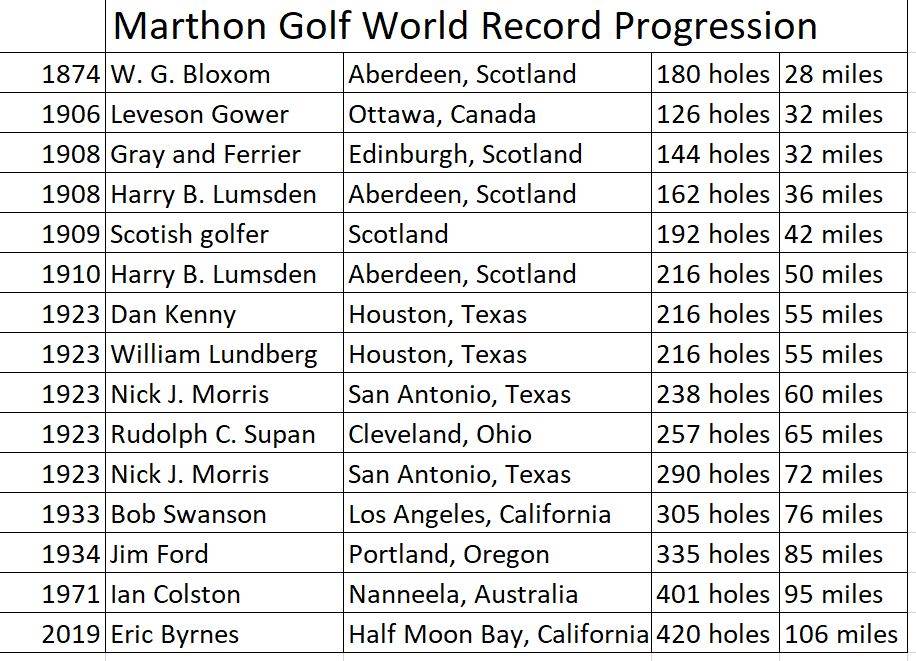

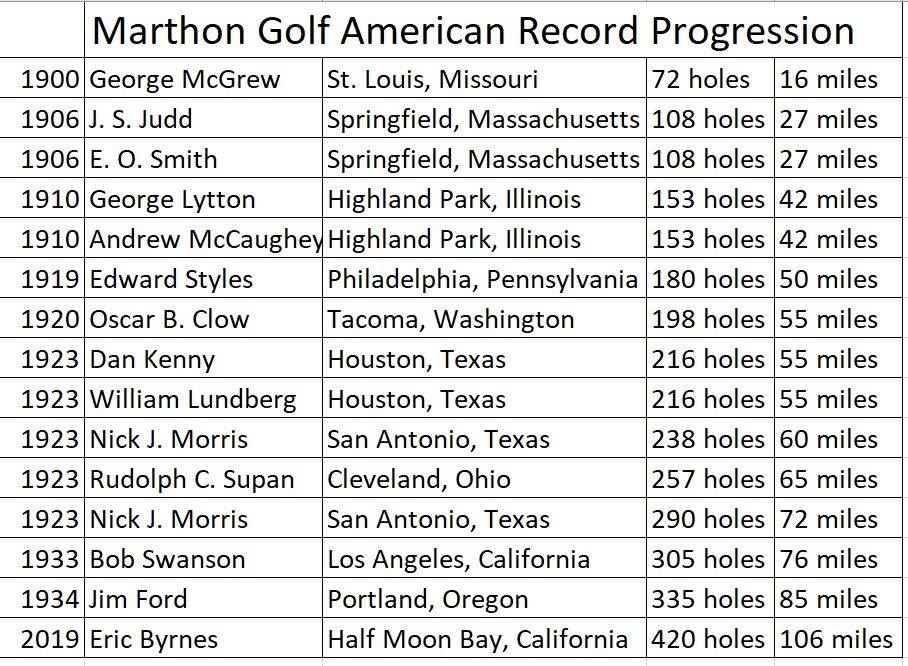

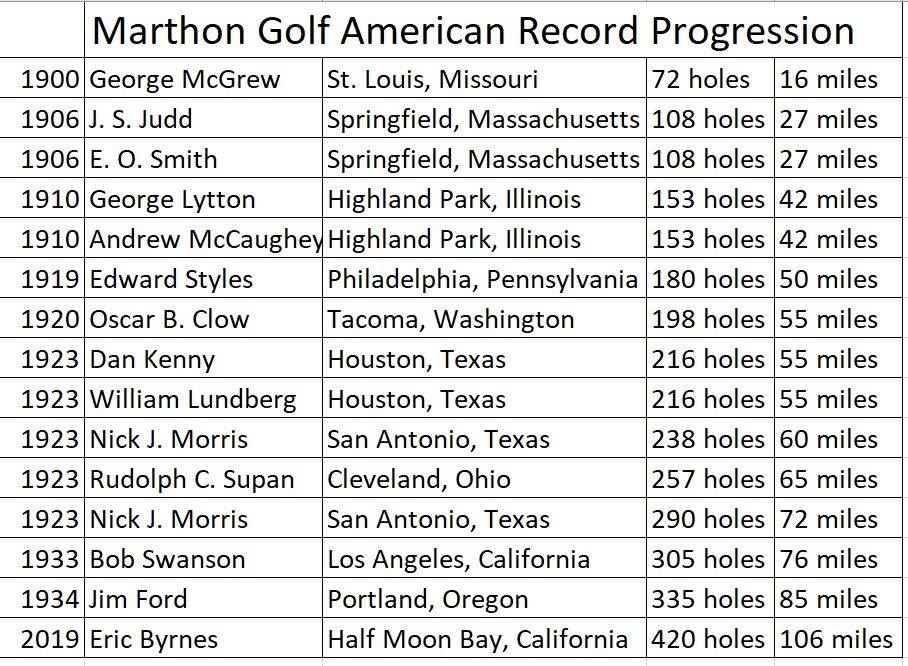

What has been called “Marathon Golf” is the art of playing as many rounds or holes as possible in a certain amount of time, usually a day (24 hours), recording strokes for each round. Golf purists have despised this activity over the years. Ultrarunners are amused and fascinated by it. In 1923 a marathon golf frenzy spread across America and again in 1934 several athletes were contending furiously for the world record.

How many miles is covered by playing a golf round? It depends on the length of the course of 18 holes. Today’s courses average about 6,500 yards. When I run every hole of my local 7,000-yard golf course straight line using a GPS, the distance comes to about 5.5 miles. Today for the average course, an average distance for a round is probably about five miles. Years ago, before golf technology improved, average courses were shorter with a length closer to 4.5 miles. There were, and still are, very short nine-hole courses where playing 18 holes could be as short as 3 miles.

Birth in Scotland

It is believed that marathon golfing was born in Scotland on a bet. In 1874, an Aberdeen Scotland golfer, W. G. Bloxom, wagered that he could play twelve rounds, 180 holes, on a short 15-hole, 2.3-mile course, and then walk ten more miles, all in 24 hours (about 38 miles total). He won the wager.

Bloxom found something he was very good at. Next, he played 16 rounds (96 holes) of the Musselburgh Links nine-hole course, for about 35 miles, against Bob Fergerson. They started at 6 a.m. and finished at 7 p.m. Bloxom averaged a score of 40 for the nine-hole rounds and won five pounds.

While the Scots were perfecting their marathon golf skills, a golfer in Canada also wanted to golf an entire day. On June 19, 1906, Canadian, Leveson Gower, of the Ottawa Golf Club completed seven rounds (126 holes) in one day, starting at 3:45 a.m., finishing at 7:30 p.m. His average score was 97, and he covered about 32 miles on a very hot day.

English point-to-point matches

In 1898, two English golfers successfully golfed a 35-mile cross-country hole from Maidstone to Littlestone-on-Sea. A wager of five pounds was placed that it couldn’t be done in less than 2,000 strokes. T. H. Oyler and A.G. Oyler took up the wager and a student at Cambridge served as the umpire to keep score, “although if he knew the large amount of monotonous work attached to it, it is very doubtful if he would have accepted it.”

The golfers took clubs with them along with about a half-gallon of balls that were newly painted, carried in a bag. Progress in the morning across fields was slow with hazards of hedges and ditches. After lunch, they played the road rather than across fields. But the balls tended to roll into the ditches on the side of the road, so they returned to the fields and woods.

They stopped for the night and were back at it the next day. While on a farm, the owner demanded to know what they were doing on his land. “We’re playing golf.” He replied, “I just request you to leave as quickly as possible.” Difficulties include strong winds and a high fence that took five strokes to get over. On the third day, one of the golfers explained, “Twice our ball hit a sheep and we were frequently in small ditches, but could generally play out.”

In 1920, a shorter 20-mile hole was played over rivers, swamps and hills near Cardiff between D. Rupert Lewis and W. Raymond Thomas. They played alternate stroke, were chased by a bull, and accomplished the hole with 608 strokes in 16 hours, losing 20 balls

Early Scottish world records

Also, in 1908 Harry B. Lumsden, a golfer from Aberdeen, Scotland, played the Balgonie Links nine times in a day, 162 holes for about 45 miles, setting a world record. He golfed for 15 hours with an average score per round of 82. A critic commented, “It is not easy to extract any useful lesson from the feats of endurance that are occasionally chronicled in connection with golf matches.” Soon after that another golfer from Scotland increased the world record to 192 holes for about 42 miles in 17 hours.

In June 1910, Lumsden was at it again in Aberdeen and accomplished an impressive 12 rounds, 216 holes, covering about 50 miles, and average 82.5 strokes per round. That world record would last for the next 13 years. Using the long summer light, he started at 2:20 a.m. and finished at 9 p.m. His fifth round was his best with a score of 77. “The excellence of the scoring is perhaps the most remarkable thing about this feat.”

First American marathon golfers

Americans also got into the “sport” early. In 1900, George McGrew, age 54, played 72 holes at the fair grounds in St. Louis, Missouri. “As far as can be figured, no one ever played as many as 72 holes hereabouts. Such play means walking fourteen miles in no less than ten hours.”

On June 2, 1906, J. S. Judd and E. O Smith of Springfield, Massachusetts, played six rounds, 108 holes for an estimated walking distance of 27 miles, the first known Americans to golf “ultra-distance.” They started early in the morning and finished late into the evening.

George Lytton and Andrew McCaughey – 153 holes

Around 1910, George Lytton, an amateur boxer, and Andrew McCaughey, a football player and oarsman, wanted to compete in a sport against each other. They chose to use the neutral sport of golf to see who could last the longest. They knew nothing about previous marathon golfing. They played at the Exmoor Country Club in Highland Park, Illinois, starting at 4:30 a.m. Both carried their own clubs throughout the day.

The two played three rounds before breakfast and decided to continue throughout the entire day and set some sort of new record. Their pace was playing nine holes every 45 minutes. They walked and did not run. “At noon both were still going strong and they stopped a half hour for lunch. During the afternoon there were many other players on the course, but word went around that George and Mac had all records distanced and players invariably gave them the right of way.”

They continued to play on, despite blistered feet, and finished at 7:45 p.m. with 153 holes, 8.5 rounds, traveling about 42 miles. McCaughey lost ten pounds during the day and had fewer strokes. But Lytton claimed that he walked the farthest.

Crazy golf match planned

Many reporters of the time could not embrace marathon golf. “Freak golf usually is the result of a new player being caught up in the chariot of fire of his enthusiasm or the result of a bet. Street golf, marathon golf, blindfolded golf, golf played in suits of armor, are some expressions of these vagaries. The trouble with a man who plays 100 holes or more in one day is that he does not get enough practice. His scores show that.”

Women join the sport

Fred Knight – 144 holes

During the World War I years, golfers took a break from marathon golfing. After the war, the “sport” really started to get attention due to the efforts by a golfer in Pennsylvania. In 1919, Frederick W. Knight (1887-1946) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, one of the best golfers of the city, sought to set what he thought would be a record of 126 holes. The actual record was still 216 holes set by Lumsden in 1910.

Knight was focused on completing the seven rounds with an average of 85 strokes or less per round. He started play on April 14, 1919 at 6:15 a.m. at the Whitemarsh Valley Country Club course in Lafayette Hill Pennsylvania. There was frost all over the course and once melted it was soaked with water.

Knight’s first round took him 1:45 and he scored an 87. By the end of four rounds he was four strokes off the 85 average. On his 7th round, “a gang of workmen passed him on the third hole. His ball lay short of the green with Wisshickon Creek between him and the green. Instead of waiting for him to make the shot, they walked on and as they passed, one of them remarked, ‘Watch him put it in the creek,’ and that is just what he did. Then to make matters worse, he hashed up the next shot and he registered an 8 on that hole.” After he finished his goal of seven rounds, he walked to the first tee and announced his intention of making an eighth journey.

Knight finished with an elapsed time of 14 hours 45 minutes, and actual playing time of 12:20. In the end he had played eight rounds, 144 holes, traveling about 40 miles, with 689 strokes. He missed his goal of averaging a score of 85 by only nine strokes. During his few breaks he would drink a glass of milk with a raw egg.

With all the attention Knight’s accomplishment caused, others quickly tried to beat Knight. Accomplishing eight rounds (144 holes) became common. One golfer kept track of all his expenses including greens fees during his 8 rounds and it came to 30 cents a mile or a total of $12, which was worth $183 in 2019 value.

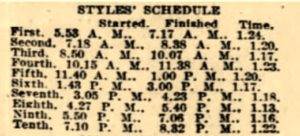

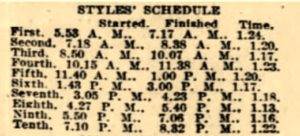

Edward Styles – 180 holes

On July 11, 1919, Edward Styles, age 48, of Philadelphia, of the Old York Road Country club, broke the true American record by completing ten rounds, 180 holes, covering about 50 miles, in 796 strokes, with an average of 79.6 strokes per round. His goal was to best Knight and do eight rounds in better than an 85 stroke average, but once he accomplished that, he continued on. He started at 5:53 a.m. and finished at 8:32 for an elapsed time of 14 hours 39 minutes.

Styles talked about his amazing day. “I could never have played that many holes if I had not been right down the alley all the time off the tee and on my brassie (2-wood) shots, nor could I have averaged under 80 for ten rounds if I had been in trouble all the time.

A Philadelphia golf champion who wasn’t a fan of marathon golf stated that after both Styles and Knight finished their marathon accomplishments, that neither regained their consistent golf talent again in normal competition.

Charles Daniels – 226 holes

Marathon golfers started to figure out how to golf many more holes in their quest for the record – do it on very short courses. In 1920, newspapers mentioned that Charles Daniels, a golfer from New York golfer had accomplished 226 holes using a very short 2100-yard, nine-hole golf course at Long Lake, New York. He traveled only about 38 miles, with an elapsed time of 16 hours. I don’t consider this a legitimate effort to qualify for a record.

Oscar B. Clow – 198 holes

On June 23, 1920, the true American record was broken again. Oscar “Ironman” B. Clow (1884-1942) of Tacoma, Washington, a “former marathon runner,” played 11 rounds, 198 holes, of the Meadow Park Golf Course in Tacoma Washington. He started at 4 a.m. and played continuously until noon, accomplishing seven rounds. A doctor then examined him and stated that his respiration was fine. Clow continued on until he finished his 11th round at 5 p.m. He traveled about 55 miles in 13 hours and used 1,085 strokes for a 98.6 stroke average for the rounds.

Clow’s caddy, Earl Williams accompanied him on a bicycle. His only duty was to watch the ball. “The caddy, although cutting corners and taking short cuts at every opportunity, was completely exhausted at the finish. Clow carried his own bag the entire way and lifted all the flags. He hit only one ball out of bounds and didn’t lose any balls.”

Arthur E. Velguth – 198 holes

On August, 22, 1922, Arthur Erich Velguth (1877-1944) of Spokane, Washington tied the American record playing 198 holes on the short nine-hole Spokane Down River Golf Course in Washington. It was thought at the time that he set a new world record, not knowing about Clow’s 1920 American accomplishment, nor Lumsden’s 1910 world record of 216.

Two months later, after hundreds of stories praising Velguth all over the country, Clow came forward and let everyone know that he also had accomplished 198 holes two years earlier on a course that was 1,000 yards further for 18 holes. Clow still held the American record.

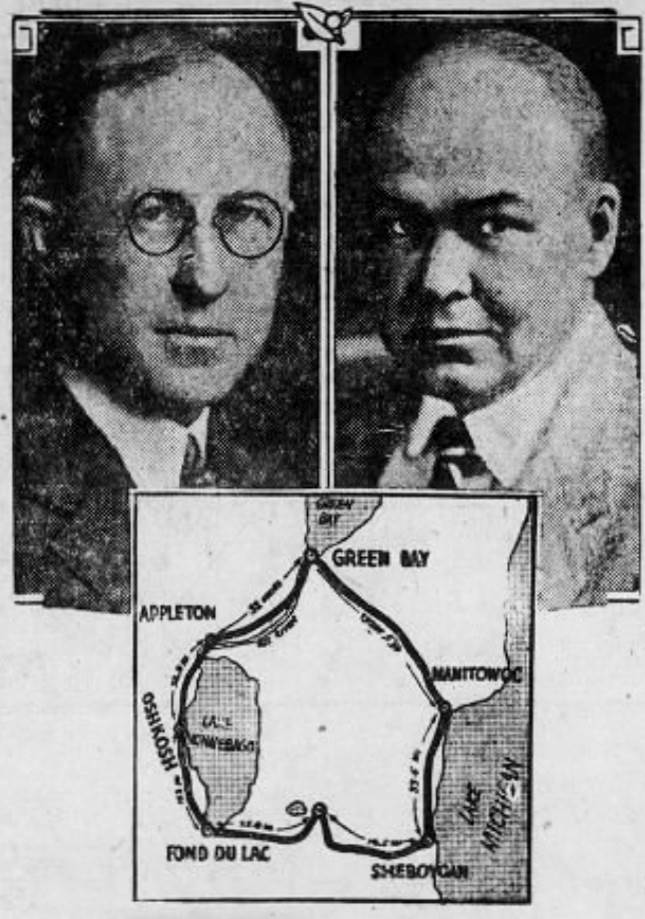

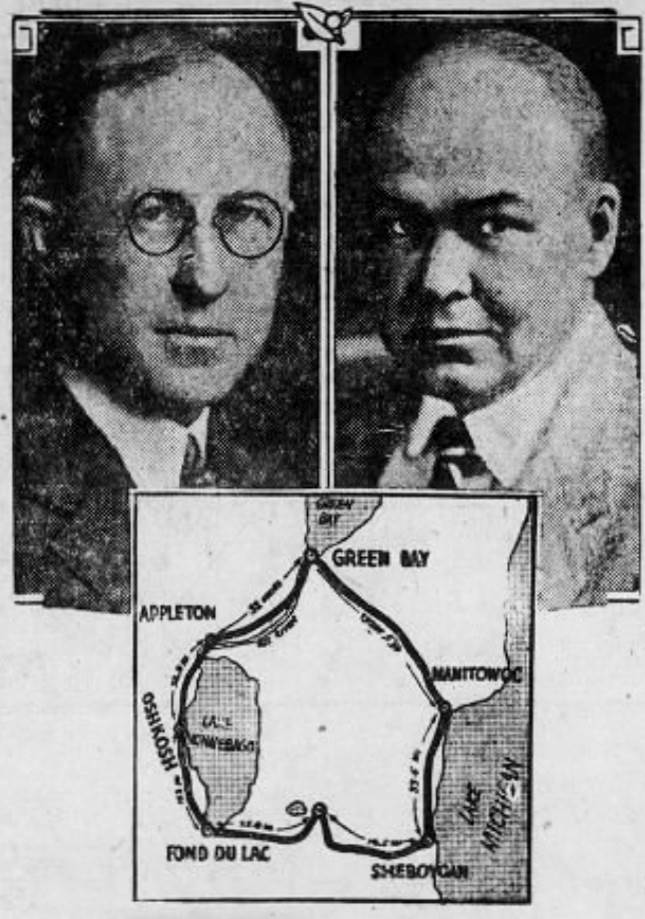

Dan Kenny and William Lundberg – 216 holes – tied world record

In 1923, a golf marathon craze exploded all over America much like the 50-mile frenzy of 1963 when everyone wanted to hike 50 miles. In 1923, a golfer or two at most country clubs across the nation set their sights on showing what they could do golfing over and over again on their favorite course.

Two golf professionals from the Houston, Texas area made their attempt at a record on June 8, 1923 at the Glenbrooke Country Club. They ended up matching Lumsden’s world record of 216 holes on a nine-hole, 3,000 yard, hilly course. They started at 4:30 a.m. with the first hole lit up by automobile headlights and ended at 8 p.m. using flashlights.

During that day it reached 116 degrees. Their elapsed time was 15:30. It was explained that with two players , It takes longer than a single player because the players stop and wait for the other to hit. Kenny played the holes in a very impressive 957 strokes for an 18-hole round average of 79.75. Lundberg used 1,003 strokes.

Nick J. Morris – 238 holes – world record

Morris used only four clubs, “a driver, midiron, mashie (wedge), and putter. From start to finish he astonished the field of 3,000 who followed his play by his long, straight drives.” Throughout the day he fed on a dozen oranges, a bottle of dry malted milk, and two ounces of raisins. Morris made a rookie ultrarunner mistake. He said, “If I had not worn high shoes in the morning rounds, I am sure my foot would not be hurting me now. I had them laced too tight.”

Morris averaged a bit more than 89 strokes for his rounds. “After he had finished the 12th round, he was forced to play the first nine holes twice for the 13th round. The greens were being watered on the last nine, making it impossible to putt. The fist nine measure some 200 yards father than the last nine.” After finishing his 13th round, he played the first two holes twice before darkness forced him to stop.

Rudolph C. Supan – 257 holes – world record

During his rounds, he only took one eight-minute rest, tired out eight caddies, and wore out two pair of shoes. He played through two rainstorms. Supan ran between shots, the first known marathon golfer known to truly try to run it. Spectators tried to keep up but soon gave up. After 10 hours he slowed down to a fast walk.

The 1923 marathon golf frenzy continues

A day later, Herbert Oberdorf, a professional golfer at High Point Country Club in North Carolina thought he broke the world record when he played 243 holes in twelve hours, forty three minutes. He likely did have the record for the most holes up to that point in 12 hours. His “elation over his feat was short lived” when he learned that his hole total was bested the day before by Supan.

Ten days later, two golfers, William McGuire, and Eddie Tipton of Washington D.C. went for the glory on the East Potomac Park course. They ran between shots, used 15 caddies, ten scorers, eating only oranges but came up short of Supan’s record, reaching 216 holes. The two wore pedometers. McGuire’s registered 69 miles for his 1,007 strokes and Tipton’s registered 57 miles for his 1,084 strokes. Both lost seven pounds during the day and Tipton played the final 18 holes in his stocking feet because of a bad blister on his right heel.

During this 1923 marathon golf craze, most traditional golfers turned their noses up to the fad. Charlie Betschler of the Park Heights Avenue course in Baltimore, Maryland said, “It’s not an endurance test, but a speed test. There is only a certain number of playing hours each day, and the one who can go the fastest will win, and that’s not golf.”

Nick J. Morris – 290 holes – world record

Morris reclaimed the world record, finishing 290 holes in 19:10 for about 72 miles. He averaged shooting 85 strokes per round. His tenth round was his best with a score of 80. Morris, a clerk at a drug company, did have difficulty with an injured knee which he nursed after the 15th round and cramped up during some swings. “He said he was through with marathon golf and does not care to compete against anyone who may surpass his record.”

The craze fades out

The 1923 marathon golf craze ran its course, especially with the untouchable record that Morris posted. Some continued to do it, including a 62-year-old Hiram Ramp who played 144 holes. A journalist wrote, “Golf is too good a game to take in such huge doses and if all sixty-year-old golfers get the craze some of them are sure to suffer and then the grand old game will be blamed.”

This definition of marathon golf was published across the country: “The idea, if any, in this game is to see how many different varieties of sap you can make of yourself between sun up and sun down. It is one of the things that makes you realize the utter futility of daylight saving.”

Golf attempt from Alabama to California

He spent one night in jail when a sheriff caught him acting suspiciously with a flashlight and golf clubs late at night. He used a driver through the countryside, a two-wood in the suburbs, and putted along city sidewalks. By March 26rd, he was playing through Houston Texas and had 21,643 strokes on his card with 73 lost balls. He had golfed for about 43 days and covered more than 500 miles.

At San Antonio, Texas, his caddy had to return home to Mobile, so Grahame was on his own. Leaving San Antonio, he lost track of his strokes so had go back to start again from the city. He had taken 31,237 strokes. The lost ball count was up to 114.

Grahame made it to Ozona, Texas before quitting on April 22,1927 after more than two months, because he ran out of funds. Up to that point he had 35,948 strokes, lost 140 golf balls, and lost 25 pounds. He had golfed for more than 900 miles.

Golfing for more than six days

Ferguson said of his followers, “The gallery ran from about 25 in the wee hours to mobs in the daytime. In the early morning hours, I would have a lot of golf professionals and newspaper men in the gallery waiting to see me go to sleep, but they were disappointed. He played pretty much non-stop for 158 hours and gave up due to badly swollen hands.

Other Depression era marathon golf fads

Also in 1930, marathon miniature golf was established at the Colony miniature golf course in Chicago. Sixteen young men and women, under the direction of M. L. Mathleu, owner and manager, started the contest that was broadcast nightly on the radio. The objective was to golf until you dropped. The winner golfed for 136 hours.

This event was soon copied in Montreal, Canada with 37 contestants. The winner played for 100 hours. “The players batted the ball around continuously, munching sandwiches and chewing oranges as they went, stroking day and night through water pipes, over dish pans and up little hills and down little valleys with tireless monotony.” It was estimated that 4,000 rounds were played by al the contestants and that they were watched by 7,000 spectators.

Robert Coy – Marathon golf fraud?

Records could have been cheated. In the early 1900s, many ultrarunners fabricated transcontinental accomplishments (see Dakota Bob) and other claims. These individuals were commonly self-promoters who accomplished stunts, and sought records for attention and financial gain. During the Great Depression, many of these solo endurance performers emerged in a desperate effort to earn money.

It appears that such was the case with at least one individual who came onto the stage in 1931, establishing spectacular marathon golf records. He was not known to be a great golfer. Each time he broke the world record, the details about the effort were very scarce. News coverage on the day of the attempt was always non-existent. This individual was Robert Norman “Chief” Coy.

In 1927 he was in the news when he attempted a “nonstop” 130-mile run from Peoria to Bloomington, Indiana and back and then planned to run 35 miles on a track in front of spectators. His run was a failure when he gave up his running stunt at mile 22 because of thick mud. In 1929 he returned to the boxing ring.

In 1930 Coy played pocket billiards for 120 hours without stopping, a world record. “As the week wore on, crowds came and went. After a couple days Coy started mistaking the nine ball of the cue ball. After 120 hours, it was over. He staggered backwards and began babbling deliriously. A crowd spilled out into the street cheering, spreading the news that Chief Coy and done the impossible.”

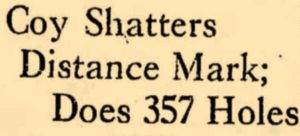

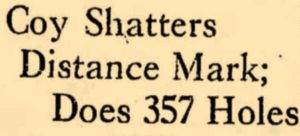

He also claimed that some of these nine-hole rounds were done in only 15 minutes, which was golfing at a six-minute mile pace during nine holes. His new 302 hole world record was likely a fraud but the public soaked it all in.

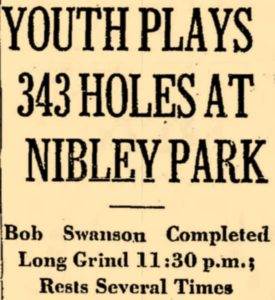

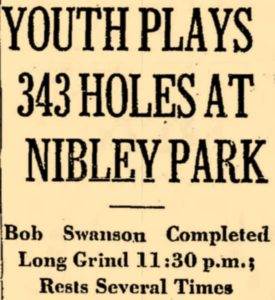

Bob Swanson – 305 holes – world record?

Bob Swanson, age 23, from Los Angeles, California, was another stunt artist who wished to beat Coy. In July 1933, he claimed to complete 305 holes of the Sunset Fields course at Los Angeles for about 76 miles. He stared around 2 a.m. and finished in 20 hours and 45 minutes. Earlier that year he claimed to have accomplished 200 holes in 17.5 hours. His 305 hole accomplishment was a dramatic improvement. Details of his 305 round accomplishment are lacking and newspaper coverage was sparse. One must be skeptical of his world record.

Coy claims 314 holes

Jim Ford – 335 holes – world record

Swanson reaches 343 holes on short course

It was reported, “While it was dark, he did not hit his ball very far and consequently scored higher. His caddy carried a huge flashlight and the streetlights adjacent to several of the holes helped out considerably.”

Given these details it appears Swanson’s accomplishment was legitimate. However, the short course must be disqualified for a true world record because he only actually covered about 60 miles. Ford still held the legitimate record with 335 holes.

Coy claims to reach 357 holes

Bill Farnham – 376 holes – very short course

Coy’s 1,000 hole attempt

“Continuous” records such as these have also plagued the sport of ultrarunning over the years. They were usually only pursued by stunt performers. The efforts were never continuous, and could have built-in rests. They were just invented records for the Guinness book of “world records.”

Conveniently, Coy wouldn’t be monitored closely, and would just have on e caddie along to carry a flashlight during the night. He planned to carry only one club, a two-iron. Starting on January 21, 1935, he played on the 6,500-yard Portrero Country Club in Los Angeles, California. True to his form, at the first tee he took a bar of iron and tied it into knots using his hands and his teeth. He also bent a half-inch bolt in a U shape.

Coy claimed to reach 300 holes during the first 24 hours. His main source of calories was ice cream with coffee. In the morning his caddie brought out to him eggs, bacon, a doughnut, and bread. Coy ate without stopping. His caddies worked in 3-4 hour shifts. “The boys who accompany him say he doesn’t talk about golf. He regales them with stories of his feats of strength.” When he hit the ball into the water, he made the boys fetch the ball out of the water. During the first night it took him seven shots to get out of a sand trap while his caddy stood there with a flashlight and watched him whale away

There was no local newspaper coverage found of the event. Coy was the only source of the news. He wrote to the Los Angeles Times and other papers. “I started June 3, 1935 and played straight through without a stop to June 5th.” Believe it or not?

What happened to Coy?

Coy retired from golf stunts but went on to other things including playing the piano for consecutive five days and nights in a store window. He got politicians to pay him to put their posters next to his piano. He claimed to hitch-hiked to every state capitols and getting the autographs of each governor. During World War II he served as a substitute mailman and jogged his route. He settled into an advertising career. He was hired to distribute advertising cards and bill around Peoria, Illinois. In 1952 it was written about him, “he fell in love with the idea of being a ‘world record’ holder no matter how obscure. He just liked the idea of having a new record and the publicity that sometimes came.”

Marathon golf into the modern era

During the next few decades after the 1930s, marathon golf attempts continued in isolated cases. There was no marathon golf published record book or even memories of records going forward. Many great accomplishments were made reaching well above 200 holes and in nearly all cases, world records were claimed. Some of these efforts were on very short courses. With better technology, fitness, lighting for courses, and true ultrarunners, the stage was set to break the records set in the 1930s.

Ian Colston – 401 holes – world record

On November 27, 1971, Ian Colston, a serious ultrarunner from Nanneela, Victoria, Australia, began his marathon golf attempt at 6 p.m. and finished at 5:15 p.m. the following day after playing 401 holes at the Bendigo Club’s course that was 6,061 yards. Colston covered about 95 miles. The club’s president and captain certified the accomplishment which shattered Jim Ford’s 1934 legitimate record of 335 holes.

In 1974, Mike Coon of Michigan claimed he broke Colston’s record with 407 holes in ten hours and tried to get that published in the Guinness Book of World Records, replacing Colston’s record. There was one big problem: Coon’s wife drove him around the course in a golf cart. What was he thinking?

Eric Byrnes – 420 holes – world record

He took a total of 3,538 strokes and his lowest round was 116. His highest was 168, so his batting arm strength came in handy for all those strokes. He covered about 106 miles and used just one club, a women’s 8-iron which he carried as he ran. A caddie friend ran with him and provided aid from carts that followed along the way.

Previously, in April 2018, Byrnes also broke Karl Melzer’s 2016 12-hour record, when Byrne achieved 245 holes. He played 13.5 rounds and ran a total of 65.5 miles at the Napa Valley Golf Club at Kennedy Park. Byrnes also had previously completed a trancontinental triathlon across America, swimming seven miles across the San Francisco Bay, biking over 2,400 miles from Oakland to Chicago, and running 905 miles from Chicago to New York City.

What is next for marathon golf? Perhaps, like ultrarunning, it will evolve into trail marathon golf using balls that have gps locators and emit sounds to be found easier.

Sources:

- Andrew Ward, Golf’s Strangest Rounds

- The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), Jun 2, 1906

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Aug 11, 1909, Jul 24, 1911, Aug 20, 1911

- The Houston Post (Texas), Aug 14, 1910

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Aug 13, 1911, Sep 3, 1930

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Aug 24, 1912

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Aug 30, 1912, Jun 8, 22, Jul 7, 1923

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Sep 10, 1912

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Jan 2, 1913

- San Francisco Examiner (California), May 13, 1913

- The Honolulu Adviser (Hawaii), Apr 3, 1913, Jul 29, 1920, Aug 5, 1923

- Honolulu Star Bulletin (Hawaii), Jul 2, 1913, Jun 16, 1925

- Buffalo Evening News (New York), Jul 26, 1913

- The Lincoln Star (Nebraska), Aug 22, 1913

- The Salina Daily Union (Kansas), Oct 8, 1913

- Oakland Tribune (California), Mar 28, 1915

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Apr 5, 15, Jul 12, 1919, Jun 21, 1923

- Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Apr 14-15, 1919, Feb 21, 1920

- The Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jan 21, 1900, Jun 21, 1918, Jan 1, 1930

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Jun 10, 1919, Jul 8 1920

- The Washington Times (Washington D.C.) Jan 5, Feb 4, 1920

- Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada), Jun 21, 1920

- The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), Jun 24, 1920

- New York Tribune, Dec 26, 1920

- The Semi-Weekly Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Aug 9, Oct 29, 1922

- Saskatoon Daily Star (Canada), Aug 22, Oct 21, 1922

- Wausau Daily Herald (Wisconsin), Aug 22, 1922

- Tucson Citizen (Arizona), Aug 22, 1922

- The Hutchinson Gazette (Kansas), Sep 27, 1922

- The Neosho Daily News (Missouri), Jun 8, 1923

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), Jun 22, 1923

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Jun 22, 1923

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Jun 25, 1923

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Jul 2, 1923

- The Coshocton Tribune (Ohio), Jul 8, 1923

- Los Angeles Times, Jul 7, 1923, Jun 12, 1935

- The Houston Post (Texas), Jul 8, 1923, Jan 22, 1935

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Jul 8, 1923

- Journal Gazette (Mattoon, Illinois), Jul 11, 1923

- The Evening News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Jul 16, 1923

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Jul 17, 1923

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Jul 17, 1923

- Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Jul 27, 1923

- Portsmouth Daily Times (Portsmouth, Ohio), Jul 27, 1923

- Austin American-Stateman (Texas), Jul 28, 1923, Apr 22, 1927

- The Richmond Item (Indiana), Apr 20, 1924

- The Dayton Herald (Ohio), Jul 16, 1924

- The Atlanta Constitution (Georgia), Aug 3, 1924

- Wilmington News-Journal (Ohio), Jun 22, 1927

- Nebraska State Journal, Feb 14, 1927

- The York Daily Record (Pennsylvania), Feb 16, 1927

- Palladium-Item (Richmond, Indiana), Feb 19, 1927

- The Anniston Star (Alabama), Apr 9, 1927

- Suburbanite Economist (Chicago, Illinois), Jul 29, 1930

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Dec 13, 1930

- The Ottawa Citizen (Canada), Sep 3, 1931

- The Ithaca Journal (New York), Mar 18, 1932

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Jul 8, 1934

- The Butee Daily Post (Montana), Sept 12, 1932

- The Salt Lake Tribune (Utah), Jun 27, 1934

- Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), Jun 27, 1934

- Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Jun 23, 1934

- Jacksonville Daily Journal (Illinois), Sep 8, 1927

- Des Moines Tribune (Iowa), Apr 11, 1952

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Feb 5, 1980

- Bendigo Advertiser, “Colston reflect on amazing feat at golf course.”

- Golfweek, “How Eric Byrnes played 420 holes of golf in 24 hours”