Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:20 — 33.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

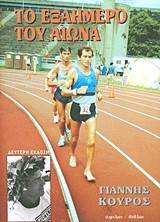

Yiannis Kouros from Greece is considered by most, as the greatest ultrarunner of all time. That is a bold statement, but there are few that dispute this statement. The late “Stubborn Scotsman,” Don Ritchie, is certainly in the conversation, Some can try arguing for certain mountain trail ultrarunners, but what Kouros accomplished, dominating for more than a 20-year period, and setting world records that have lasted for decades is nothing but mind-boggling. Every ultrarunner needs to know about Yiannis Kouros and his accomplishments. One of his competitors, Trishal Cherns of Canada, said, “There’s the elite, the world class, then there’s Yiannis.”

Yiannis Kouros was born on February 13, 1956 in Tripoli, Greece, a city of about 20,000 people at that time. His father was a carpenter and the family lived in poverty. They did not always have enough food, requiring Yiannis to perform his first manual laboring at the age of five. He could not afford to go to the movies so he went to a stadium to run for fun.

Sports was also a refuge from his family trouble. Kouros explained, “I had a misfortune in my family. When I was born, my father thought I was not his own, he was of course wrong. For that reason, he used to lash out on me. My mother was uneducated and instead of nurturing me she fought me even more. So I grew up in a hostile environment.” He spent much of his childhood with his grandparents who were strong disciplinarians.

In elementary school, he was awarded first place in the long jump. In high school he couldn’t stay home after school because of family troubles, so he had to go somewhere and went to track. He began formal athletic training and started running races at the age of sixteen. At first his coach dismissed Kouros as being “a mediocre athlete who just didn’t have the build to go fast.” But he progressed to be one of the top high school runners in Greece. He was a junior champion at the 3, 000 and 5,000 meter distances. After high school he left home and lived on his own in Athens for a time.

In 1981 at the age of 25, Kouros started building a house for himself in Tripolis which would take years to complete. He worked during the days as a guard at the athletic stadium and in the evenings worked on his house alone and trained about twice per day. He averaged only 2.5 hours sleep per night. By the end of the year, he asked the Sports Council to send judges to witness his attempt to run 100k, running on a 20k road course, seeking to set a national record. He finished in 7:35 but no judges came.

Spartathlon

Kouros signed up, hoping to be the first Greek finisher. It was his first ultramarathon! He jumped right from the marathon distance to about 156 miles (251 km)!

World record ultrarunner Eleanor Adams of England also signed up, the only woman in the race. When she took a bus ride to preview the course, including the climb over the 3,500-foot pass on Mount Didimas, she commented, “It’s going over that mountain in the dark that worries me a little. It’s a tiring course for someone who’s only run round and round a track. This race will be a real challenge.”

Kouros said, “I eventually reached Sparta. I beat not only the Greeks but, the whole lot. The best runners and world champions of ultra-distances were competing. I won with nearly a three hour difference from the second runner. I arrived at 4:50 a.m. at the crack of dawn when everybody was fast asleep. I remember the mayor and the bishop had to get out of bed, the award presenting girls had to get dressed in a hurry.” He won in an official time of 21:53:42. There were 15 other finishers that first year. None of three American starters finished including Ed Dodd of New Jersey who dropped out after 112 miles (180 km) due to dehydration. Eleanor Adams finished in 32:23:23.

Kouros was surprised too. He said, “I’ve never run so far in my life. I just wanted to see what I could do against the experienced runners.” He received international attention and there were serious uncertainties in some people’s minds if it was a legitimate win. He explained, “There were doubts in Sparta on the side of the English who refused to give me the cup as they regarded humanly impossible the fact that a distance of 250 km could be covered in 21:50.” A French runner who chose to remain anonymous said, “I do not make an accusation of unfair play, but still I say to myself, ‘perhaps he made a favorable turn by accident.’ Because this performance, it is not possible for any man.’” Ultrarunning pioneer Dan Brannen said, “He is the only runner for whom an accusation of cheating eventually became an honor.”

Kouros returned the next year and ran even faster, finishing in 20:25 which has stood as a course record through the present day. In total he won Spartathlon four times and has the four fastest times ever. To help today’s ultrarunner understand just how fast that was, his best time was nearly two hours faster than Scott Jurek’s fastest Spartathlon.

1984 Three-Day Austria

Kouros proved his doubters wrong when he went to Austria on Easter weekend of 1984 to run a 320km (198.5-mile) three-day road race in Austria. During the stage race he averaged 66 miles (106 km) per day of nonstop running at a pace of seven-minute-miles. He was never seen walking, even while passing through 30 aid stations. His slowest mile during the three days was faster than eight minutes. He won by more than three hours, even with taking a wrong 3 km turn that cost him about 20 minutes.

1984 Six-Day New York

Next, Kouros wanted to break world records. He said, “When I realized that I was good at ultrarunning and that a world record was something I could do, I had faith in writing history, because records remain as a written testimony, inspiring after 100 or 200 years, just as I am today inspired by Pheidippides and others as they have written history. When you break a world record, you interject into a portion of the history of athletics what you have done.”

Kouros sought to go after a mystical record that had not been broken for nearly 100 years, the 6-day record of 623 miles (1,002 km). This was set by George Littlewood in 1888 at Madison Square Garden in New York City. It was the oldest established running world record.

Fred Lebow, the race director said that the biggest headache preparing for the race was trying to satisfy all the runners’ musical tastes on the loudspeaker in the old stadium under the Triborough Bridge. He said, “It is impossible. The Greek runner wants bouzouki music. Siegfried Bauer from New Zealand wants Bach concertos.”

The long race began with 25 men and six women. Kouros took off fast, reaching 9.5 miles (15 km) in the first hour, running a 2:42 first marathon, and opened a quick lead. Modern-day six day races were still new and the press was fascinated. One report stated, “The runners carried on, wearing an odd variety of pajamas, turbans, running caps, T-shirts, open-toes sneakers and even pedal-pushers stuffed with ice cubes.

After day one, it was reported, “Shortly after noon, the mysterious and legendary Yiannis Kouros of Tripoli, Greece, stepped gingerly off the running track at Randalls Island and helped himself to a dish of boiled potatoes and a quart or two of water laced with honey and lemon. He also put his feet up for the first time in 24 hours. Stopping only for the most vital reasons, he finished the first 24 hours of competition with 164 miles, 46 ahead of his nearest competitor, Don Choi. Some of the other runners wonder if the nonstop beginning would catch up with Kouros.”

Kouros later revealed, “I had a fear of remaining a vegetable for the rest of my days, as after 24 hours, I felt my body no longer operating and I was carrying it without its consent. I thought I would not be able to walk again, though I made a conscious decision to write history. To expiate myself, I saw it as a sacrifice in an ancient drama. I knew I was leaving something behind me.”

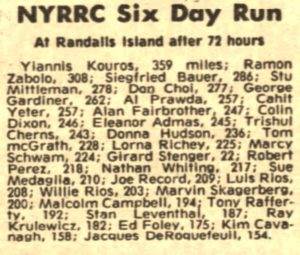

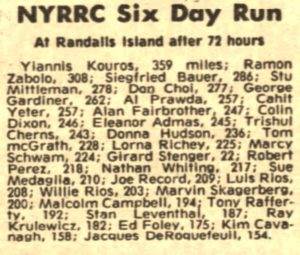

He ran 102 miles on day two and 93 miles on day three. His 266 miles after 48-hours set a world record. After 72 hours, he had logged 359 miles which shattered the known world record of 318 miles. He was 51 miles ahead of the second-place runner, Ramon Zabolo of France.

Kouros shared more thoughts about his effort, “I was running very fast, and because my toes were bleeding very much, many believed I would have to drop out. There I experienced how important the mental attitude is. I come to a point where my body is almost dead. My mind has to take leadership.” He experienced great highs where his mind took over his body. “I reached the stage to look at my body from above, from outwards, I mean like an out-of-body experience. I mean that your body has surrendered and you see yourself from above and behind and you somehow guide your body ahead. I am talking about incredible moments.”

Tom McGrath of New York had set up his tent next to Kouros and they seemed to get along well. Stopping to go to the bathroom which was quite far off the track took too much time, so Tom said his job was to “shield” Yiannis when he wanted to do it on the run, on the track.

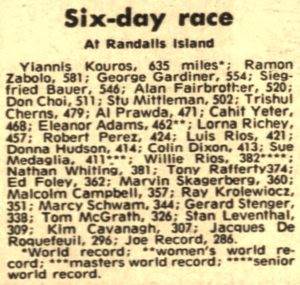

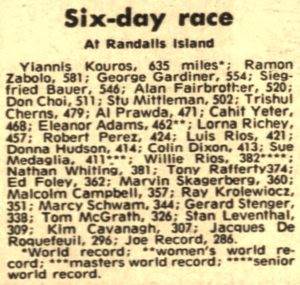

In the end, Kouros shattered the all-time world record of 623 miles (1,002 km) and went on raise the record to a staggering 635 miles (1,022 km). He ended up winning a total of $7,500. After he finished, he said, “I am very, very tired. I am really surprised that I broke the record. I didn’t think it was humanly possible and I doubted that the man ran that many miles such a long time ago.” It was speculated that it would take another century for anyone to break the record again. But it would only take five months.

Training for Records

Kouros was training about two hours each day on the mountainous roads near Tripoli. He trained himself and had no coach because there was no one in Greece who coached ultra-distances. As he trained, he composed songs in his head and then would write down the music when he got home. When asked what he thought about when he raced, he explained, “I run with a kind of film inside my head, looking at pictures of my childhood, my time in the army, my first girlfriend. I stay cheerful indefinitely.”

1984 Sri Chinmoy 24 Hours

He led the field of 56 runners for the first ten miles but was closely followed by George Gardiner. Kouros hit the marathon mark at 2:48 and 50 miles at 5:27.

His running was continuous, without walking. He only stopped to change into warmer clothes for the night. He explained his strategy that evolved for 24 and 48 hour races. “When I run the 24 hours, I never sleep. I hardly sleep on the 48 hours unless I have an incredible need to. I sleep for only 10 minutes on the second night. I avoid stopping. I am terrified in giving up a race or at least pausing a race. When I pause, it is for the bare minimum time wise.”

Along the way he beat Don Richie’s 1979 100-mile road world record of 11:51. Kouros hit 100 miles in 11:46:37. He next lowered the 200km world record to 15:11:48 and finally went on and passed the world 24-hour record of 170 miles with two hours to go. After that he walked more and finished with 177 miles (284 km), a new road 24-hour world record.

A fellow runner observed, “It was fascinating to watch Kouros running by himself. Since we were on an enclosed mile loop, you were constantly aware that he was moving at an incredible pace, never appearing to slack off and totally within himself, never acknowledging anyone else.”

1984 Colac Six Days

In late November 1984, the City of Colac, Australia established a new six day track race around their Memorial Square, which was measured and certified at 400 meters per lap. It was the first six-day race in the southern hemisphere. When Kouros arrived he was disappointed. “I found the course not suitable and the organization just as bad. The surface was irregular. I saw the track and wanted to go home.” But he stayed. Fourteen runners started with some of the same runners from New York. Kouros again dominated.

But as the race was concluding, one of the most surprising things ever happened in a ultramarathon. There were about 5,000 spectators, including about 1,500 Greeks cheering Kouros to break his own world record. But with only 200 meters to break the record he stopped, and “went on strike.” He refused to continue until his appearance fee of $5,000 was secure and $10,000 additional prize money would be paid as promised. According to his manager, it was a gesture of disgust at promises that had been rescinded.

His manager said, “Kouros was upset because it was hard work for him to run that distance. He doesn’t consider running six days for fun and why should he break the record if there is no reward.” He waited for 97 minutes until there was agreement and then went on to extend his world record by just 360 meters. One news story said, “his gracelessness took much of the shine off his efforts.”

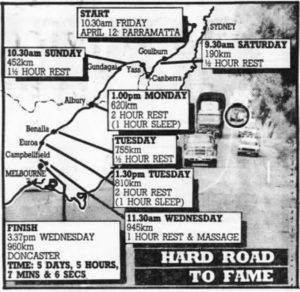

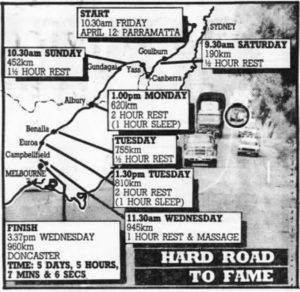

Westfield Sydney to Melbourne

Two days before the 1985 start at Sydney, Kouros said little more than that he was ready to do his best. On race day at a Sydney shopping center, the starting gun was fired and the field of 27 very talented ultrarunners started their very long run.

Kouros took the lead in the first few miles and left the other runners “in his wake.” He was never challenged after that. At about mile 45 he was already seven miles ahead of New Zealand great, Siegfried Bauer. His competitors hoped that by the third day Kouros was fade because he they knew he was not used to running on roads in Australian conditions.

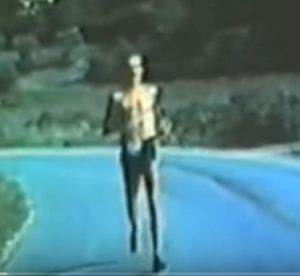

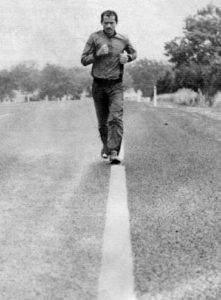

An article observed, “Kouros can run like no others before him at such long distances. While the majority of ultramarathoners employ a shuffling gait, Yiannis runs like a regular marathoner.” He continued ahead at a “seemingly mad and unendurable pace.” During the first 24 hours covered about 160 miles. It soon became a race against himself and he moved further and further ahead of the main field.

By the time he approached Melbourne his race was a national front-page story and on prime-time TV news. Near the late stretches he finally began to walk, wanting to be careful in order to break the course record. He was about 90 miles ahead of the next runner.

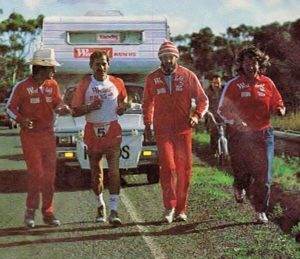

Before entering Coburg, a city consisting of a large Greek population, he stopped for a shower, shave, rest and a good meal at a small hotel. His crew suggested that he take a long sleep, but Kouros wanted to get the race over and done with. On his way again, he entered the crowded streets of Coburg where Greek nationals greeted their Greek hero. “For the last 40 kilometers, Kouros’ countrymen lined the streets waving Greek flags, throwing streamers, and covering him in flowers, while special escorts assisted him through the crowd.It seemed as if the entire Greek community was converging on the finish area. As Kouros ran into the finish area, pandemonium reigned. No one could have anticipated the power pushing enthusiasm of a mob of hero worshipping Greeks.”

He commented, “The tragedy in our sport is that we cannot celebrate our victory when the race is up. In all the other sports, when the race is finished, they go to celebrate and rejoice. In our case you can not do anything. The day after the race, you feel like death itself.” A columnist concluded his coverage of Kouros’ race with, “Thank you Yiannis Kouros for showing us ordinary people what one extraordinary person can do. It leaves us no excuse for not trying.

Running in a Hurricane

A race official reported, “An hour before the start, the winds had picked up to 30-40 mph gust, knocking over our tents for counting and flattening anything not tied down. We made decisions to have counters sit in dry cars near the start/finish area to count the laps. Tables were tied down with heavy construction blocks. Food and aid for runners and helpers was given out of a van. The runners gathered to the starting line dressed in raincoats. A moment of silence ensued just before the start. A steady rain was falling. The runners moved forward as the horn sounded.” Wind gusts continued to increase.

A TV newsman reported that the City was closed down, all the parks were closed, all events canceled, “except for this long race in Flushing Meadows. Guru Sri Chinmoy said, ‘God will protect the runners.’ I sure hope so.”

At night the streetlights didn’t come on along the park roads. Several cars were positioned to use their headlights to light the course. “At the far turn one could glance at the other parts of the big public park and see bright car headlight shine through the damp haze everywhere.”

Footing was bad but Yiannis continued to run circles around everyone. He reached 50 miles in 5:38 and 100 miles in 11:53:31. In the end he increased his 24-hour World Record to 178 miles. Only 39 of the original 78 starters hung in there to the 24-hour finish.

Ultrarunning Life

Kouros’ dominance continued. In 1986 he won the Sri Chinmoy 100 in New York, in 11:56, just ten minutes off his road 100 world record. He ran the race with a fractured toe, which was still healing from a few months earlier. Kouros rarely held back even when not feeling well. He said, “I consider my races as exceptional chances which will not be repeated. You are never sure you can run again after a race as you could have sustained a serious injury, so you try to lessen the time on everything, on sleep, on changing clothes, end eating, you do it on the move, not standing.”

“I would say that ultrarunning is a way of life. It is neither an everyday party nor a mourning. It fluctuates. When you feel good you fly. When you feel bad, you regain your strength. When you are at your lowest exhausted, having nails missing, knees blown up and a sore back you try to inspire yourself and overcome these obstacles. At low points, I hunt for inspiration

Kouros said, “I am not the best runner. If I were to train with other runners, they would beat me. But in a race, I feel something different. There is something extra in a race – the mind.” He really didn’t like racing in track events. The presence of other runners distracted him and he preferred races like Spartathlon and Sydney to Melbourne. He also felt badly about lapping his competition on tracks, believing that is amounted to an act of humiliation. He said, “when I am alone with my thinking, I have another world.”

Kouros had strong opinions on what was true ultrarunning. He believed that 50 km and 100 km, 6 hours and 12 hour races were not long enough to be called ultras, that “this category of races is meant for specialists.” His definition for true ultras also did not include trail races or solo runs. The 100-mile distance also didn’t meet his definition because he felt that the race must go “beyond 24 hours, as a runner has to face the whole spectrum of the daytime and nighttime and be able to continue.”

1,000 Mile Race

Kouros started the 1,000-mile race at a slower pace than he usually ran in his races, with “just” a sub-8-minute-mile pace. But he still reached 144 miles on the first day. He didn’t get much sleep the second day because of all the noise at Flushing Meadows and the planes flying overhead, so he rented a camper. After six days he had covered 639 miles. He was sick the eighth day with only 69 miles, but went on to finish 1,000 miles in a world record of ten days, ten hours, a record still held to the present day.

Apartheid Controversy

Eventually, in order to run in Sydney to Melbourne, in front of cameras with race organizers at his side, he signed the UN pledge denouncing South Africa’s policies. The anti-apartheid movement declared that they would no longer push for Kouros to be ineligible to run in events. Greece was slower to decide on his eligibility.

During this troubling period of time, in 1989, Kouros lost his job he held for nine years accused of not producing enough work. Perhaps it also was related to the eligibility. His employer had the perception that he was focused more on his national profile from races and awards. Kouros said he left Greece in 1990 because his boss got involved in politics with a shift of the government and didn’t pay him for nine months. His dispute wasn’t resolved and the prime minister of Australia invited him to move there as an immigrant. Kouros was also frustrated that in Greece the sports focus was almost solely on soccer. He decided to move. In Australia he worked at a sports shop as well as singing at a club and was given a house.

1991 Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Controversy

Kouros claimed his 1991 participation would be well worth that amount given the $20 million of publicity that the race generates for Westfield. He said, “The other runners pay money out of their pockets to participate and pay their crews because they love the sport and Westfield gets all the rewards. It is not fair. Without me, the race will suffer. It can no longer be called the greatest ultramarathon.”

The race commented, “The guy is the greatest ultrarunner of all time and we’d have loved to have had him in the race as an official starter, but there was no way we could afford that amount of money. He’s been great publicity for us with his rebel run, but he won’t be abiding by the regulations of the Westfield Run.” Kouros did finish his “rebel run” well ahead of the official field. The Westfield race did suffer without him. Westfield withdrew their support after the 1991 race and it was no longer held after that.

Pausing on Racing

He would spend eight to ten hours a day in his studio with keyboards and guitars writing songs in Greek. But he still ran. He would compose songs as he ran, taking inspiration from things he saw. He said, “Music in the mind is the best drug for a runner.”

An Impressive Comeback

Around 1994 Kouros became an Australian citizen and he started competing again, this time for Australia. As part of his comeback In 1996, Yiannis, raced in a 48-hour championship at Surgeres, France, on a 300-meter track. He went on to finish a massive 294 miles (473.495 km) for 48 hours, setting a world record that stands to the present day. As of 2019 he had accomplished the top six 48-hour performances of all time.

In his last training run before this race, he had fallen and broken three ribs but was able to endure the pain through this world record performance. After the race he asked to be taken to the hospital where x-rays confirmed the fractures. Also in 1996 at Coburg, Australia, he covered 182 miles (294.504 km) in 24 hours for yet another world record. It was very impressive to see that after a few years off he was able to come back and still be the best in the world.

Pushing so hard for records had its risks. Kouros was human and once told a scary tale of a race in 1994. “I ran the seven days circling Tasmania. On the second day we had a snowstorm and I braved it wearing a snow cap. On the 5th day we had bad weather again. Halfway through that day, I felt my heart beating irregularly, as if it was not working. I asked for a warm tracksuit, gloves and a cap but later on I started to not feel well in my heart again. I asked for a second tracksuit and I was hindered with a low body temperature, immobile, then something is afoot. It was the first time I said what I hardly say, ‘Forget it, it isn’t worth it.’ I thought I was dying. I even asked that my remains would not be left in the mountains of Tasmania. I was thinking of my family and I considered them to be of a greater importance than any sport.”

Quest for 300K in 24 hours.

Yiannis had a long-standing goal to run 300K (186 miles) in 24 hours and was frustrated several times coming up short due to weather or injury. In late 1997, at the age of 41, he would finally reach his goal. His achievement came at Sri Chinmoy 24-hours at Adelaide, Australia on a 400-meter track at the Olympic Sports Field.

Yiannis went for it, not holding back. He hit the marathon mark in 2:59:59, 100K in 7:15 (new Australian record), 100 miles in 11:57:59, and 200 km in 15:10:27, a new world record. He was beginning to feel the pain but pushed on. By 17 hours he had covered 138 miles. He had a “bad patch” and his laps started to slow, so he stopped talking and was very focused. His crew continued to help, putting small pieces of food in his mouth as he passed each lap. When dawn arrived, he felt revived. He began shouting at his crew for more fuel.

With two hours to go, he needed to run 11.1 more miles to reach his 300 km goal. He made it! He He reached 300 km in 23:43:38 and ended with 303.5 km or 188.5 miles, a world record that would last through the ages. When he finished he declared, “I will run no more 24-hour races. This record will stand for centuries.” His record was 17 miles further than anyone else had ever gone in 24 hours. He did compete in more 24-hour races, seeking to do even better. As of 2019, he has the top four 24-hour performances ever.

Basel 24 Hour Race

Return to Greece

At about 1997 Greece started negotiations for Kouros’ return Greece. Agreement was made on some points so he could return. Through the work of his friends, he was offered a job as an officer at the Greek Air Force. He returned to his home country at the end of the year.

By 2000, Yiannis had won 53 ultramarathons. That year Runner’s magazine proclaimed him as the seventh best runner of the 20th century, but the best ultrarunner of all time.

1000 kms in Six Days Again

In 2005, at the age of 49, Kouros sought to reach 1000 km again in six days on the track at Colac, Australia. He had reached 1000 km three times before on loop courses and also reached that distance unofficially during the 1989 Sydney to Melbourne race in a staggering 5 days, two hours, and 27 minutes.

At 2005 Colac, Kouros was successful again and raised the world record to 644 miles. On the last day, two busloads of Greeks arrived from Melbourne to cheer their champion over the 1000 km mark. The crowd erupted when history was made. During that race he set four world records and broke personal records that he had set 20 years earlier. He attributed his ability to do all of this to “staying active and creative, and finding inspiration.”

2013 Across the Years

I was able to meet Kouros in 2013 when he ran the 2013-14 6-day Across the Years race. His Greek crew was set up right next to my personal aid station and I enjoyed watching them assist him during the race. They were intensely diligent and Kouros was focused and demanding. Yiannis dueled for six days against Joe Fejes. Kouros covered 550.1 miles, but Fejes beat him with 555.35 miles. Kouros’ crew was very upset about the loss and that Fejes’ strategy was to copy Kouros’ pace and stay ahead. Kouros was not used to coming in second place.

The Greatness of Yiannis Kouros

Dan Brannen spoke of the secret behind Kouros’ greatness. “You won’t find the secret to Kouros in either his ability or his training. His marathon best is only 2:24. He rarely takes a training run longer than 12 miles, and is never over 80 miles per week. He follows a strict vegetarian diet that has no red meat. poultry, fish, eggs, or dairy products. Surely the reason for his success lies beyond nutrition, but nobody now following the sport is likely to find it. Like the Trinity, pi, and pyramid power, he is a classic mystery. And the best approach to take with a mystery is to stop trying to solve it and just believe.”

Ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy still wanted answers and researched how Kouros prepared, trained and ran. He provided a detailed analysis in his book, “Training for Ultrarunning” available on Amazon.com. He wrote “Yiannis Kouros is a unique ultrarunner in that his aim was to totally disregard his opponents. His primary competitive focus was the races of 24 hours and above, where he used a technique of disassociation by concentrating on composing music or poetry, and excluding the demands and protests of his body. He would go out hard, build up a sizeable cushion and then run the race the way he wanted. His running style evolved as his strengthened his upper body. Even pace gradually supplanted the faster starting pace of his earlier years. Studying the event, learning constantly, and obsessive attention to detail are all traits worth emulating.”

Kouros said, “In ultrarunning there are no real limits. One can go on and on. I try to achieve something special in each race. I believe that more and more people will start with ultrarunning, and I feel I belong to the pioneers now. What Pheidippides did, going to Sparta just for a message and bring back a message to the Athenian, I’d like to think of myself as a messenger. I want to inspire, to give the message that something is doable. Everything is possible as far as I am concerned as long as you go for it.”

Sources

- Yiannis Kouros official website

- Elias Giannakakis, Yiannis Kouros – Forever Running

- 1984 6 Day Run https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EbXDUmEBvCQ&t=1562s

- Marshall, 1984 Ultradistance Summary, 71.

- Mike Agostini, “Kouros: New Sydney-Melbourne Record”

- Dan Brannen, “How Good is Yiannis Kouros”, Ultrarunning Magazine

- 1985 Sri Chinmoy 24 Hour

- Andy Milroy, “Kouros Claims His Ultimate Victory,” Ultrarunning Magazine, 11/1997

- Andy Milroy, “The Basel 24 Hours 2/3 May, 1998”

- Yiannis Kouros, “A War is Going on Between My Body and My Mind,” Ultrarunning Magazine, 3/1990

- Trishul Cherns, “Yiannis Kouros – A Worthy Successor to Phidippides,” Ultrarunning Magazine, 1-2/1985

- Feidippideios Athos Facebook Page

- Billings Gazette (Montana), Sep 30, 1983

- The Guardian (London), Feb 4, 1983

- The Winona Daily News (Minnesota), Oct 2, 1983

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Jul 4, 1984

- The Paducah Sun (Kentucky), Jul 4, 1984

- Daily News,(New York City), Jul 6, 1984

- Asbury Park Press (New Jersey), Jul 8, 1984

- Wausau Daily Herald (Wisconsin), Jul 3,9, 1984

- Pensacola News Journal (Florida), Jul 7, 1984

- The Montgomery Advertiser (Alabama), Jul 8, 1984

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), Jul 25, 1984

- The Age, (Melbourne, Australia), Dec 3,31, 1984, Apr 14-20, 1985, Apr 4, 1987, Oct 6, 1997

- The Daily Times (Salisbury, Maryland), Nov 4, 1984

- The Sydney Morning Herald, May 16, 1989, Mar 22, May 16-17, 22 1991

- Leader-Telegram (Eau Claire, Wisconsin), Feb 20, 1989