Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 35:27 — 42.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

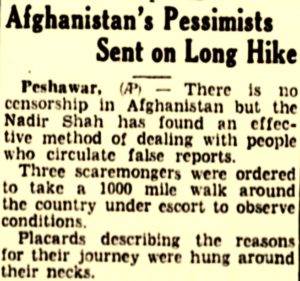

In the 1980s running 100 miles started to become more popular for the non-professional runner to attempt. By 2017 some in the ultrarunning community viewed running 100 miles as fairly common place. In recent years a saying of “200 is the new 100” emerged as a few 200-mile trail races were established, meaning that 100 miles used to be viewed as very difficult but 200 miles was the new challenging standard. This may be true, but what about running 1,000 miles? Will 1,000 milers ever be the “new 200?” What? Who runs 1,000-mile races?

In 1985 America’s first modern-day 1,000 mile race was held in Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens, New York with three finishers. The 1986 race was probably the most famous modern-day 1,000-mile race held with a show-down of several of the world greats. But most ultrarunners have never heard about 1,000-mile races. 1,000-mile attempts in one go have taken place for more than two centuries.

A curious 1,000-mile frenzy took place for about ten years in England during the early 1800s by professional walkers/runners. They took on huge wagers making those who succeeded, very wealthy men. These 1,000-mile events attracted thousands of curious spectators who also wagered and spent much of their money at the sponsoring pubs during the multi-week events.

This will be a three-part series on 1,000 milers. Two main formats for these 1,000-milers took place during early 1800s. In Part 1, the stories will be told about walking 1,000 miles, “go as you please” as fast as the pedestrians could, to reach the distance within a certain number of days to win the wagers. They were not really interested in achieving best times. They were simply interested in reaching 1,000 miles in time to win the wager and gain lots of money donated by spectators. Massive amounts of money changed hands in bets.

In Part 2, stories even more famous will be told about reaching 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours, an effort commonly called, the “Barclay Match.” With this format the pedestrians were required to walk a mile during every successive hour, a strange battle to establish bizarre sleep patterns for nearly 42 days. Part 3 will include the modern-day 1,000-mile races.

Very Early 1,000 Mile Attempts

Running or walking the 1,000-mile distance in an event has taken place for more than 250 years. Before the modern era of ultrarunning (post-WWII), attempts to reach that specific distances were mostly conducted as solo attempts involving wagers.

The earliest known 1,000-miler was attempted in 1759 by George Guest, a wagoner from Warwickshire, England. At Birmingham, England, for a “considerable wager”, Guest attempted to walk 1,000 miles in 28 days. He knew that he needed to walk about 36 miles per day. His course was in the area of Mosely-Wake Green, about two miles from Birmingham. He only walked 31 miles the first day but from then on stayed on schedule. Half way through, on day 14 he was back on schedule at mile 490. It was reported, “He is perfectly well and it is thought he will perform the whole in the time.” By day 21 he had walked 720 miles.

With two days to go, Guest still had 106 more miles to go. He was feeling fine and to show off a bit, “he walked the last six miles within an hour, though he had a full six hours in which to complete his task.” He finished on February 1, 1759. The next month he again attempted to walk 1,000 miles, this time in 24 days for 1,000 guineas in five-pound shoes. His attempt took place on horse grounds in South Lambeth, a southern district of London. It is unknown if he was successful, probably not.

1,000 Miles in 20 Days

George Wilson

With his endurance walking skills, Wilson, a small man, only 5’4”, started to look for long distance walking wagers. His first one involved walking the 84 mile length of the historic Roman Hadrian’s Wall within 24 hours.

In September, 1808, it was announced that another pedestrian, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice of Ury would attempt to cover 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours, performing one mile only in each hour. (We will get to that in Part 2). Wilson read about these plans and believed he could accomplish 1,000 miles in less than half the time, in 20 days.

In October of 1808, Wilson, probably wanting to accomplish 1,000 miles before Captain Barclay, quickly took on a challenge to walk 1,000 miles in 20 days. Bets were in his favor. It was reported that he started the challenge by the end of the month if so, was not successful. A couple months later bets were again being taken for a Wilson 1,000-mile attempt. He was required to walk 50 miles each day within a 14-hour daily time limit. He was also required to drink only water during his journey. If successful he would win 1,000 guineas. His planned start date was April 11, 1809. Each day he would start from Shoreditch Church and walk to the 25-mile stone on Cambridge Road and back. It was reported, “The attention of the sporting circles is much attracted by this match. High odds are betting against the performance.” It appears that the event never took place.

By 1810, Wilson was selling pamphlets in Kent which at times required him to walk 40 miles per day. In 1814 he fell on hard times as his marriage was breaking up and he couldn’t pay a 20 pound debt to an uncle. He was thrown into debtor’s prison. While imprisoned he continued his ultra-walking ways, walking 50 miles in 12 hours in a small prison area, 11×8 yards, making 9,026 turns. He won a wager of 3 guineas, one shilling which helped him get out of prison. Less than a month later, Wilson announced his interest in covering 1,500 miles in 30 days near London.

The 1,000-Mile Riot

On September 11, 1815, at the age of 50, Wilson again tried to accomplish walking 1,000 miles in 20 days and it turned out to be one of the strangest and most famous stories in early pedestrianism. His walking course was a one-mile triangle near the Hare and Billet pub at Blackheath, about eight miles east of London.

Rules for his walk specified that he must reach 50 miles in each of his 24-hour periods. The landlord of Hare and Billet agreed to feed and lodge Wilson, but after the second night he moved out because the pub was just too noisy when he needed to sleep, so he was taken to a nearby home each night. During his walk he ate “fowls, jellies, strong broth, teas, milk, eggs and a moderate quantity of Madeira wine”

On Day 5, Wilson was on schedule but it was very hot, and the dust was quite annoying. Wilson’s feet were dreadfully blistered. The next day he walked in good spirits. At times he was interfered with by some rowdy spectators who were betting against him. After finishing his 50th mile that day around 11 p.m. he was carried home “amidst the cheers of his friends.”

Halfway through, on the 10th day, Wilson had sore feet but doing well with a 16-minute-mile pace. He took stops every four miles. Curious crowds had grown to about 7,000 people. The dust kicked up by the crowd affected his breathing. He had asked that his route be roped off to give him protection from the pressure of the crowd but that was impossible. The area was “a complete scene of riot and confusion.” Some rich men who were betting in favor of him published hand-bills for the crowds that included, “Give him room! Keep back! George Wilson, the pedestrian, most earnestly entreats the spectators to keep a greater distance, so as to allow him sufficient space to walk with ease and have the benefit of the air.”

On the 11th day, the daily betting odds were against him. A couple disgruntled bettors tried to attack him and he fought back with his fist. His assaulter tried to get Wilson arrested. Previously two pretended friends had given him a drink on a hot day. Soon afterword his stomach became ill and it was determined that they had tried to poison him. As if walking 1,000 miles wasn’t hard enough, he had to face daily stress from all these people who wanted him to fail.

Wagers were estimated totaling, 5,000 guineas. Men with bayonets were sent out to clear his path. With the huge crowds the pub was doing amazing business. They sold 1,296 quarts of beer in one day. The Tartar fair was well established near the pub and had put up many tents and large booths with musicians and alcohol. A theater came to put up attractions but was stopped by the property owner. But some circus acts were approved including a trapeze. An elephant sat in front of the pub. Every time Wilson completed a mile lap, a roar would come from the crowd. It was an amazing spectacle.

The nearby roads were the scene of terrific confusion. The road to London was blocked up with all types of horse-drawn vehicles. Screams of terror could be heard. There were collisions between carriages, stage coaches, carts, donkeys, and horses. Vehicles were “pressed forward with an unwise impatience amidst the general crush. Friend and foes seem to have forgotten all the usual courtesies of good manners.”

Local authorities were not pleased with reports of drunkenness, prostitution, and riotous acts. On the 12th day alcohol was banned outside the pub and the booths were cleared. On the 13th day a warrant for Wilson’s arrest was issued but not yet executed. On Day 14, the authorities would not allow him to walk in their town on Sunday so he was taken to park in a nearby town where a half-mile out-and-back was measured off. Back in Blackheath there was great confusion as horse-drawn carriages were going in all directions in search of Wilson. “The inmates inquiring most anxiously of each other, whither he had gone.” Heavy rain fell and he only completed 32 miles before midnight. Torches and lanterns were used to light his way. He continued on through the long night and reached 50 miles by 5 a.m.

On day 15, after just a few hours of sleep, he was “under evident marks of a depression of spirits, and great bodily fatigue.” He made a statement at the day’s start, “In having accomplished so much of my task, I have done as much (700 miles) as any pedestrian who has preceded me, in the same time, and I am now about to commence three hundred more miles, which I hope I shall be permitted to perform without molestation. I sincerely hope the magistrates of the county will not feel it necessary to disturb me.” He completed his 750th mile that day.

After just one mile on the 16th day, it was rumored that a “posse of constables” were on the way to arrest Wilson. His friends took him off the course to the home he was staying at, but eventually the authorities showed up and he was placed under house arrest. The charge was for disturbing the peace with “a very tumultuous assemblage of people from the surrounding and other parishes and occasioning a considerable interruption to the peace of the inhabitants.”

Wilson was disappointed but gracious, addressing his friends and supporters with thanks and then was taken to bed where he slept all day. A hearing was held days later but eventually Wilson was “discharged and conducted home in triumph, decorated with ribbons, and accompanied by the shouts of the multitude.” But, the damage was done. It had been nine days since his walk was interrupted. A public collection was taken and he still received his 100 guineas.

It turned out that the warrant for his arrest had been conducted illegally. Ten magistrates had signed a blank warrant that was filled out later. That was why Wilson was released. The locals were not happy with a particular unpopular magistrate and a “great number” of people knocked on his door in the morning asking him “if they might have permission to walk over the Heath on their way to town.”

The 1,000-mile “Pedestrian Mania”

Despite Wilson’s failure to finish 1,000 miles because of interference, other pedestrians and inn keepers noticed that it had been an enormously successful profitable event. Plans were immediately put in place to mimic Wilson’s event to achieve 1,000 miles in 20 days.

William Tuffee

Just a month later, in October 1815, William Tuffee, age 35, a laborer with a wife and five children, started his copy-cat walk in the town of Rochester, Kent, England, about 30 miles east of London. The spot for the walk was Cossack Field, where a 220-yard roped off out-and-back grass course was constructed in a hollow of a hill beside Cossack Pub. At one end of the course was a chair for Tuffee and at the other end was a British flag.

Before holding the event, they made sure that it was supported by the local magistrates so they wouldn’t have the same difficulties that Wilson experienced. Tuffee agreed to attempt to reach 1,000 miles in 21 days and bets were against him succeeding. His only training was walking 20 miles to work and back now and then. For his event it did not matter how many miles he walked each day, he just needed to reach 1,000 miles in 21 days.

Early on, all went well and Tuffee stayed right on schedule. After five days, he was at mile 248. Tuffee walked with two canes in his hands, stayed very upright, and did not “ramble” as Wilson did. On the 6th day he began at 5 a.m. and was in “high spirits.” He completed 13.5 miles by 9 a.m. and then went to his tent for a half hour breakfast of coffee and eggs. By noon he reached 22 miles and reached 46 miles by about 9:45 p.m.

The next day the crowds started to grow. “Rochester exhibited a greater scene of bustle than has been remembered for a considerable length of time, by person, some in carriages, some on horseback, and others on foot, arriving in all directions to view the performance of Tuffee, whose Herculean task is now the general topic of conversation.”

On day 7 some rowdy members of the crowd “threw impediments into his path.” He received bruises to a leg causing him considerable pain. It was reported that the crowd was loud, “given to shouting and singing to such an extent that Tuffee, who had been staying at the Cossack Inn, had to repair to his own home, some small distance away, as they were disturbing his rest.”

The rain poured on day 12 and at night Tuffee wore a huge coat, with a pair of boots that had large nails in the bottoms so he wouldn’t slip. He held an umbrella and trudged along at 3.5 miles per hour. His feet were soaked and bad blisters formed. He finished that day with 534 miles. He was about 36 miles behind schedule but he was confident that the knee pain would stay away. “He had every hopes of finally accomplishing his undertaking” with only nine more days to go. Unfortunately, on day 13, Tuffee quit after going 553 miles. The course was in terrible shape.

It clearly bothered Tuffee to fail at his 1,000-mile quest, so just about a month and a half later in December, he participated in a new stunt, a 1,200-mile relay with his 12-year old son. When he rested, his son could continue to keep the mileage ticking up. Their course was in Maidstone, England, near the Roebuck Inn. They reached the half-way point, 600 miles on the 11th day. They succeeded and reached 1,200 miles on the 20th day. The boy covered 502 of those miles.

John Baker

The promotors of Tuffee’s attempt were very savy. If Tuffee didn’t finish, they had John Baker waiting in the wings to replace him and thus keep the spectators coming. Once Tuffee quit, Baker was to start his 1,000-mile, 21-day walk just three days later on the same course in Rochester.

Baker, a Rochester native, was 33 year old and was 5’5”. He was very used to training “through the most dreary parts of Kent.” It was rumored that Baker gained his stamina while smuggling goods for long distances. The evening before his start, he made a bet that he could perform one mile on the course in less than 10 minutes. He completed it in nine minutes.

Because of the troubles that Tuffee had experienced with the rowdies who wanted him to fail, the mayor of Rochester sent assurances to Baker that he would receive officer protection during his walk, making sure no one tried to interfere his attempt. The one requirement was the Baker didn’t run between 10 a.m. and noon on Sundays during church services.

The next morning, Baker came to the start, accompanied by members of the Cossack Cricket Club, all who loudly cheered him. He wore an overcoat, several waistcoats, thick three-pound half boots, and a common round hat. His friends wanted him to wear shoes, but Baker insisted to walk in his favorite boots. It was reported “He carries in his hand a tick hazel stick, which he swings as he walks along in his gait he rather stoops.”

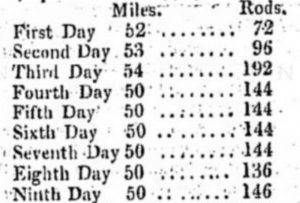

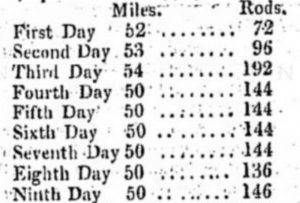

His first day went well. He had a plain diet of wine and beef tea and reached about 60 miles, maintaining a pace of about 15-minute miles. He reached 12 miles by 8:30 a.m. and stopped for breakfast, resting only 20 minutes. He reached 52 miles by 7 p.m. and retired for the night. The ground for the course was good and nearly the entire day the place was full of spectators.

Baker became concerned that some strangers trying to be friends with him had gained access to the room that he would use to rest. One had tried hard to get him to accept some pills which Baker refused. The committee over the event feared that someone might try poisoning Baker and ordered a sign be put on Baker’s door “that no person whatsoever, during this match of his, shall be permitted therein, except themselves and his known friends.”

Baker would often hum his favorite song, “Within a mile of Edinburg Town” as he took his breaks in his room. On one day, Baker was offered bribes to quit, including a very large one for 100 guineas. He “scornfully” rejected such offers.

On the 14th day, the weather was “more tempestuous” than the oldest settlers could ever remember. Baker started out at 4 a.m. in the terrible storm accompanied by attendants with lanterns. But it was so muddy that he and his pacers gave up after a few laps. He tried again a 6 a.m. but again gave up after five miles until the storm passed. “The ground had become so slippery that to attempt to get on he could not.” At 9 a.m. he finally could continue, but by afternoon he had traveled only 17 miles. That day in town several windows were blown in and chimneys were down. Most of the tents pitched at the Cossack were totally leveled except for a grand stand tent. A large wagon carrying an 8-ton elephant was moved to higher ground. On day 16 he reached 770 miles.

On day 19 when Baker was on his 50th mile for the day, “a fiddler came upon the course and accompanied him, playing some lively airs, which seemed to volatize his animation; for he intended to finish that 50th mile, but at the end of it, he, to the astonishment of everyone, danced a jig, and said he would add another tick top the clerk’s score.” He walked the next mile in less than 14 minutes. As he leaving the ground, he turned back to the course and said, “I’ll walk another mile merely for recreation.” He did another 13-minute mile and then danced the hornpipe dance.

On his 20th day, he really wanted to reach the 1,000 mark even though the bets were on 21 days. He needed 74 more miles. By 10:30 p.m. he had 50 miles. To the astonishment of his friends, he showed amazing determination to continue through the night. He stopped three times to dance a hornpipe. At about 5 a.m. he reached 1,000 miles and went one more mile for good measure. He then retired to the Cossack public house “amidst the acclamation of the spectators and the roaring of a huge elephant.”

Apparently 1,000 miles was too easy. Bake issued a challenge to George Wilson to walk 1,500 miles in the shortest period of time but it never happened.

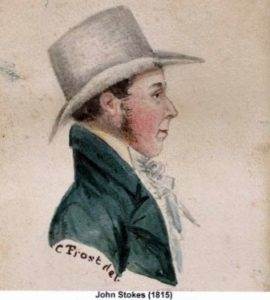

John Stokes

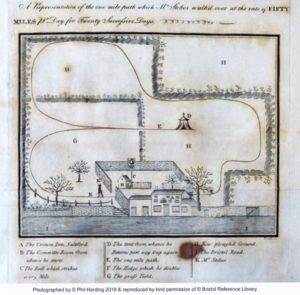

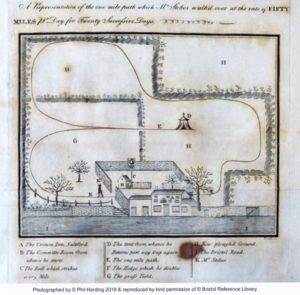

Stokes, like the others, teamed up with a local inn, the Crown Inn at Saltford, England on the road between Bristol and Bath. The landlord of the Inn, Mr. Cartwright, constructed a one-mile gravel walkway course in a field behind the inn. Stokes started on November 20, 1815. Each day Stokes planned to start at 6 a.m. and reach 50 miles, but he wasn’t required to walk that mileage every day.

Stokes generally wore “a green frock jacket, a silk plush waistcoat, net-pantaloons, with a white hat, and shoes of strong calfskin with very stout soles, thickly studded with nails.” The report said Stokes was “remarkably upright with a firm step, seemed a particularly affable gentleman and he converses freely during his progress with the bystanders”.

On his 20th day, he did very well, reaching 50 miles in a little less than 12 hours. He walked “with all that apparent ease which accompanied him even to the last moment of his Herculean task.” An “immense” crowd from the surrounding country greeted Stokes when he reached his 1,000-mile goal. Friends put him in a coach and drove a circular route to be cheered by the crowd. His actual walking time was 214:07:14.

1816 1,000-Mile Attempts

After all those back-to-back and concurrent 1,000-mile attempts, it didn’t stop. In August 1816, a pedestrian, Evans, age 22, weighing only 112 pounds, started at Brighton to attempt to walk 1,000 miles in a very speedy 17 days. His course was at the Bear Inn, near the horse barracks. In six days, he reached an impressive 345 miles. On Sunday he rested during church services and then walked at a pace of 5.5 miles per hour before “an immense concourse of spectators which considerably annoyed him.” But he continued on “prosecuting the task with undiminished perseverance.” With three days to go, he still had 174 more miles. The crowds were pretty thick. “The road leading to the cavalry barracks was one continued line of company.” However it was remarked that the novelty of these 1,000-mile attempts and were not the public spectacles as they used to be.” At 4:21 a.m. Evans succeeded and reached his 1,000 miles in about 16 days, 22: 21, the fastest known 1,000-mile time up to that point.

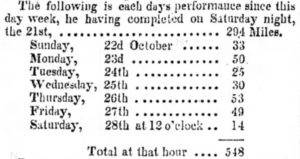

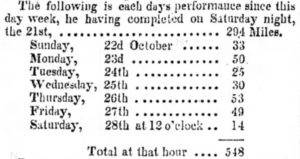

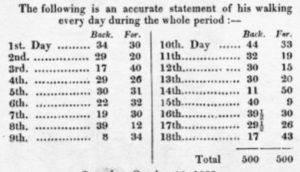

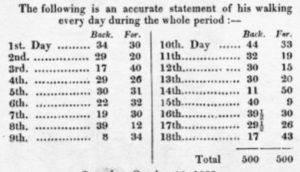

In November 1816, the pedestrian pioneer George Wilson started another attempt to walk 1,000 miles at the garden of the “Ship Launch Inn” at Hull, England. This time he attempted to do it in less than 18 days, taking time off on Sundays. Admission of one shilling a day was charged to watch, or four shillings for a week. After day 9, he was close to schedule with 495 miles. But on day 10, stiff winds blew out the lamps on the course forcing him to finish that day with just 42 miles. With two days left he still had 106 miles to go and the bets were 4-1 against him that day. But he made it!

Wilson finished in a record 17 days, 23:19:10. He “concluded his arduous task amidst the cheers of populace, and a torrent of rain.” A band was playing at the finish and accompanied him twice around the course. But Wilson later complained very publicly that all he got from the people of Hull was funds only sufficient to pay for his expenses during the 18 days. A newspaper editorial was glad he didn’t get paid much, “It will tend to put an end to such exhibitions. If every idle fellow who chooses to take an extraordinary long walk is to be paid for his trouble, we should never have an end of such useless exertions, nor of the evils they bring on the indolent and thoughtless, who lose their time in witnessing them.”

1817 1,000-mile attempts

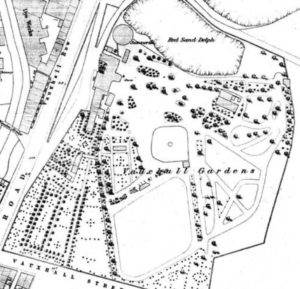

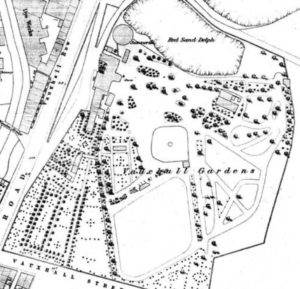

In 1817 George Wilson again reached 1,000 miles in less than 18 days, this time at Mr. Tinker’s Vauxhall Gardens, at Collyhurst. Vauxhall Gardens was a popular place for recreation such as dancing and concerts. The gardens also had “excellent grass for horses is available at moderate terms.” There was plenty of room for spectators to cheer Wilson on. Later that fall he made another attempt at Bowling Green Tavern, Scotland Road in Liverpool, but stopped short because the crowds were too disruptive. In 1820 at age 54, Wilson was capped his 1,000 my career by successfully reaching 1,000 miles in 18 days at Chelsea, Middlesex, England.

In October 1817 a female walker, Esther Crozier started to attempt 1,000 miles in 20 days on Croydon Road. As was typical of the time, people were amused that there could be women pedestrians and the papers reported mostly on their appearance and clothes. “This heroine is rather of prepossessing appearance, about the middle size, and very effeminate. She wore a brown stuff gown, colored shawl, white stockings, and tout shoes.” On the third day she was completely drenched through. Her friends wanted her to change her clothes but she just pushed on. She was still doing well on the 7th day. There were only a few curious people who stopped by to watch but nothing compared to what the men received. Neighbors started raising money for her. Unfortunately, on the next day she resigned her attempt.

Daniel Crisp, a bricklayer of Paddington, took a different approach to reaching 1,000 miles. Instead of going back and forth or on circles on short courses, he took the approach to walk back and forth between cities. In October 1817, Crisp started a journey to go more than 1,000 miles by walking back and forth from Oxford to London on Uxbridge road for 20 days. Each one-way trip was about 61 miles. He succeeded and reached 1,134 miles in 21 days, attracting about 10,000 spectators. The following year, in 1818, on the same road he reached 1,037 miles in 16 days, 23:08 despite some terrible flooding. The Thames River left its banks and spilled onto the road in five locations and he had to wade a quarter mile through the water. It was called, “the greatest pedestrian task ever performed.” He likely reached 1,000 miles early on the 16th day but his split time is unknown. His official time including the 37 extra miles was the fastest known 1,000-mile time for the next 60 years.

John Wright, a tailor, was born in 1765 at Huggate, Yorkshire, England. In 1817 Wright walked 1,000 miles in less than 20 days on the New Cut (canal road) at Bristol. He succeeded with 11 hours to spare. Later, again in November 1817 he extended the challenge by walking 1,200 miles in 24 days at Saltford on the Bath road (the same venue as John Stokes used in 1815. Wright again succeeded with nine hours to spared. In In 1819 he increased the speed, by walking 1,200 miles in 20 days at Gloucester, with 2:10 to spare averaging about 60 miles per day. He likely reached 1,000 miles in about 16.5 days which was probably close to Crisp’s unknown 1,000-mile split time in 1818. In 1824 at the age of 53 he made his final attempt at 1,000 miles in 20 days going back and forth between Maidstone and Tunbridge. He lasted only six days due to “constant sickness of the stomach, and never having been able to eat anything for the whole six days.”

The Great Pedestrian Contest

In 1817, the first known 1,000-mile race was announced. But it wasn’t just 1,000 miles, it was planned to be 2,000 miles in 42 days. The contestants were the “Rochester Pedestrian,” John Baker and Josiah Eaton, a 46-year-old baker from Woodford, Northamptonshire, England. The event took place in an open area called Wormwood Scrubs used to exercise cavalry horses. The course was right by the Mitre pub, starting on May, 7th. In the betting odds, Baker was favored 2-1. The winner would get 100 guineas. They each would walk on quarter-mile out and back courses that were parallel, 20 yards apart. At one end, two large tents were put up for each contestant and their crews. When it would get cold, both had rooms in the pub. The rules agreed to, acceptable to local authorities, was that the men would walk only between 3 a.m. and 11 p.m.

After seven days, both had passed 300 miles and Baker had a seven-mile lead. After two weeks Baker was just barely ahead and they had passed 600 miles. They reached 1,000 miles on the 21st day, with Baker 13 miles in the lead, a very close race. Baker kept to a strategy to stay ahead but keep it close, probably for betting purposes. On some rainy days the course became impossible for them to walk very long because of deep puddles.

The Duke of York and other “persons of distinction” came to watch and the common people came “in huge numbers.” The largest crowds came on the 38th day. A nearby canal was choked with boats. In one day, 2,200 gallons of beer were sold at the pub. It was estimated that about 50,000 people came to watch on that Saturday as Baker maintained a 9 miles lead. With a couple days to go, Baker became ill due to smoking an extra pipe, allowing Eaton to catch up a little.

In the end, Baker came away with the win, reaching 2,000 miles in 41 days 21:07 with nearly a ten mile lead. Eaton also squeaked under 42 days with just ten minutes to spare. All the most famous pedestrians of the time came to witness the finish. A huge dinner was held in the pub after the finish.

While this incredible event was taking place, another pedestrian was doing his own 2000-mile in 42 days quest. He was Burnett and was walking at Tooting. He started about 17 days before Baker and Eaton, probably trying to steal attention. By about day 27, Burnett had reached 1,282 miles and was “then going on in grand style.” Apparently, he did not finish.

Backwards Walking

With all the attention brought to Wormwood Scrubs, promoters didn’t want to see the crowds go away. In the days following the 1817 2,000 mile race, others came on the course trying to achieve 100s of miles walking backwards! Darby Stevens, age 25, started to walk backwards on July 11, 1817. He had the aid of a rope stretched on the course which he could grab to keep his balance. He succeeded in walking 500 miles backward in 20 days.

The next day Daniel Crisp of Paddington took his place without the aid of a rope and walked 280 miles backwards in only seven days. A newspaper editorialized, “We have reason to believe that the idle scene of walking backwards, which continues to disgrace even Wormwood Scrubs, is encouraged for the very worst purposes and the public disgust will be still more excited, when we state that it is meant to continue these vicious scenes throughout the whole of the summer. Another of these reprehensible matches is already determined upon.”

Continuing 19th Century 1,000-mile Attempts

Walking/running 1,000 miles has lasted for ten years and the mania was petering out. But there still were some determined pedestrians that wanted to go the distance for good money. There still were plenty of the 1,000-mile Barclay Matches being conducted which will be covered in Part 2.

In 1821 he tried it again at the Prussia Gardens in Norwich. This time the local magistrates put an end to the event on the 8th day after he traveled 390 miles.

Finally, in 1823, at age 34, he was very successful when he covered 1,500 miles in 30 days. Early he would start from the Mouth of the Nile pub in Worcester and walk to “the Lamb” at Cheltenham and back for 50 miles. He would start at about 4:00 a.m. each day and finish around 8:30 p.m. for a 16.5 hour 50-miler, averaging about 20-minute miles including stops. With two miles to go, “his path was lined with spectators and he was joined by a band of music and flags to escort him into the city. His step was firm and elastic, and his pace so rapid that those who would keep up with him, were compelled to amble, almost trot, and scarcely exhibiting the least symptoms of fatigue.”

By day 13 he had reached 715 miles but was 17 miles behind schedule. “His ankles are much swelled and is much oppressed in walking backwards, having fallen of nearly a mile an hour.” He walked with a stick which prevented his hands from swelling. He successfully completed 1,000 miles with 12 minutes to spare. It was said, “This feat may be pronounced one of the most arduous in the annals of walking.”

In 1824, a “pig jobber” (distributor), W. Verral, better known as “Lad” attempted to walk 1,000 miles in 20 days for a wager of 30 pounds. His course was from Swam Inn in Horsham, England going on the London road out 25 miles and back. He used many friends “to render him comfortable in respect to refreshments, clothing, etc.” He proclaimed, “Lad will not give in until he can go no longer, and of that Lad is not afraid.”

1,000 miles “Go as you Please” Comes to America

The 1,000-mile quest came to America in October 1830. Newsam, a pedestrian from England, took on a wager of $1,000 to walk 1,000 miles in 18 days at the public gardens of Philadelphia. He was successful. Toward the end of his journey some men frequently got in his way in attempt to defeat his effort. “To protect him against these, he was armed with a formidable weapon, and accompanied during the latter part of his walk, by a bodyguard of several stout men.” He went on his way in triumph.

In 1868, Fred W Symons, a 24-year-old law school student at University of Wisconsin was a “new walking sensation” in the area. He had always been fond of walking and was 6’0” weighing 137 pounds. went to Chicago where three men promised to pay him a total of $3,000 if he could walk 1,000 miles in less than 22 days. Symonds only trained for 15 days but took on the challenge. Part of his route was walking from La Crosse, Wisconsin to Chicago, Illinois, about 285 miles. At Hessler’s Garden at La Crosse, Wisconsin, he reached 1,100 miles in 20.5 days. He earned a bonus by doing 100 of those miles in 19:45. To earn the bonus he had needed to break 24 hours.

A balcony was built for Mrs. Weston and family to watch his progress. It was draped with stars and stripes. For his 865th mile, he clocked it in 10:29. At the start of his last day at 5:00 a.m., he still had about 64 miles to go. His fastest mile that day was his 975th mile in 11:22. By 7:00 p.m. he only had 15 miles to go and he reached 1,000 miles at 10:41 p.m. His moving time was 15:41 but he took about 21 days including the Sundays he took off. Altogether he took only 150.5 hours rest and did an additional 7 miles walking to and from his lodgings. His fastest mile was the 995th which he covered in 9:15. It was said, “He accomplished the feat with great ease and appeared fresher at the finish than he did at the onset.”

Head-to-Head 1,000-Mile Match

In 1890, the famous American pedestrian champion, Daniel O’Leary and James T. Lowry of Waco, Texas, raced 1,000 miles on a track at the Oak Cliff baseball park in Dallas. The winner would get $500 plus 2/3rd of the gate receipts. The contest started on August 3, 1890. By day 5, Lowry led 372-356. It was said that Lowry was in better condition than the champion but O’Leary had phenomenal grit and endurance. On the 7th day, O’Leary’s feet were in bad condition and he was suffering from a sore heel and a sore toe. In the waning days, it was close. O’Leary held an 858 to 855 lead, and both mean had sore feet and the long struggle was taking its toll. Lowry won in about 15 days likely a world best mark but his exact time is unknown. O’Leary was ten miles behind when Lowry won.

1,000 Miles Into the 20th Century

By the turn of the century into the 1900s, walking/running 1,000 miles in the fastest time possible disappeared. 1.000-mile Barclay challenges were still conducted. Stay tuned for their bizarre story in Part 2. Stunt artists attempted a few 1,000 mile stunts to get attention.

In 1926, George Hassler Johnston of New York, “the hunger hiker” attempted walking 1,000 miles between Chicago and New York City for $1,000 in 30 days without eating any food, only drinking about two gallons of mineral water per day. A doctor traveled with him along with an experienced walker to pace him.

A friend wrote, “The walk carried him over hills and valleys, through wind and rain, and the summer’s heat and through crowds that flocked along the way. Handshaking, interviews, posing for pictures and making short health talks consumed almost as much of his energy as the walking.”

After 20 day and 577.8 miles, as he climbed to the top of the Allegheny Mountains in Pennsylvania, he had lost nearly 38 pounds and weighed 120 pounds. His feet had shrunk three sizes. One news outlet commented, “If there is any point to be gained by the completion of his journey, we hope he makes it, but so far as we can learn the hiker is putting his body on the verge of the scrap heap. At the top of the mountain range he was so weak that he gave up the attempt.

In 1935, Julius Slade, age 37, walked 1,000 miles for $200 pushing a wheelbarrow from Mississippi to Chicago in 30 days. He was a former baseball coach and left with just 35 cents in his pocket. He finished with 75 cents.

In 1947, Bert Couzens, age 27 of Essex, England walked and ran 1,000 miles in 333 hours, in less than 14 days, on the Romford Stadium track. It was reported, “At times he had rapid pace setters, the greyhounds that chased the mechanical rabbit almost nightly on the dog track. At no time during the long walk did Bert have more than five hours of sleep. Most of his resting was done in one hour naps. He ate only lean meat sandwiches and a few apples. He drank buckets of tea and smoked hundreds of cigarettes.” He was asked why he did it and replied, “I’m fed up with seeing us as a race being mostly beaten in every angle of sport and enterprise. I’m a patriot and feel like doing my bit in keeping up the prestige of the old country.”

And thus ends the crazy stories of fast 1,000-mile walks before the modern era of ultrarunning. Stay tuned for Part 2 for the crazy 1,000-miles in 1000 hours matches, a mile every hour, or how about a mile every half hour with no misses!

Sources:

- Andy Milroy, “The History of the 1,000 Mile Race”

- The Shipwrecked Mariner, Volume 31

- George Wilson: The Blackheath Pedestrian

- S. Marshall: Richard Manks and the Pedestrians

- Allen Guffmann, Sports: The First Five Millennia

- John Stokes (1815) A Brief Memoir

- John Stokes (1815) Journal of twenty days

- 1815: John Stokes’ 1,000 mile walk at Saltford

- Herbert M. Shelton, “Working During The Fast”

- Walter Thorn, Pedestrianism: Or, An Account of the Performacnes of Celebrated Pedestrians.

- George Wilson, A Sketch of the Life of G.W. the Blackheath Pedestrian

- Derek Martin, “The 2,000 Mile Race: Pedestrianism in the Early Nineteenth Century.”

- The Newcastle Weekly Courant (England), Feb 3, 1759, Nov 17, 1821, Dec 31, 1869

- The Leeds Intelligencer and Yorkshire General Advertiser (England), Jan 30, 1759, Mar 20, 1759, Dec 31, 1808

- Jackson’s Oxford Journal (England), Jan 20, Feb 3,10, 1759, Dec 24, 1808, Nov 4, 11, 1815, Oct 8, 1817, Sep 7, 1822

- The Public Advertiser (London) Feb 8, 1759, Oct 7 1772

- The Ipswich Journal (England), Oct 1, 1808, Nov 5, 1808, May 26, 1810, Nov 4, 1815, Nov 23 1816

- The Observer (London), Oct 30, 1808

- The Morning Post (London), Jun 5, Dec 27, 1808, Oct 28, Nov 1, Dec 13, 1815, 31 Oct 1817

- The Bury and Norwich Post (England) Dec 21, 1808, Jun 3, 1812, Oct 25, 1815

- Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle (England), Aug 26, 1811, Aug 22, 1814, Dec 18, 1815

- The Exeter Flying Post (England), Jun 15, 1809, Oct 26, Nov 2, 9, 16, 23, Dec 14, 1815

- The Hull Packet (England) Jul 18, 1809, Jul 11, Nov 28, 1815

- The Lancaster Gazette (England), Nov 11, 25, 1815, Dec 30 1815, Sep 20, 1823

- The Leeds Mercury (England), Nov 11, 18, 1815

- The Morning Chronicle (England), Sep 30, 1808, Aug 1816, Sep 21-26, Nov 2, 15, 1815, May 1817

- The Times (London), Dec 12, 1815

- The Champion and Weekly Herald (London), Jul 15, 1838

- Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle (England), May 18, 1818

- The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post (England), Jun 22, 1822

- The Evening Post (New York), Feb 26, 1824

- North-Carolina Free Press, Nov 2, 1830

- The Horn of the Green Mountains (Vermont), Oct 19, 1830

- New York American (New York), Oct 26, 1830

- The Weekly Standard and Express (England), Jan 19, 1878

- Belvidere Standard (Illinois), March 26, 1878

- The Indianapolis news, 26 Apr 1878

- The Yorkshire Herald (England), Jan 1, 11, 1878

- Fort Worth Daily Gazette 8, 15-16 Aug 1890

- Messenger-Inquirer (Owensboro, Kentucky), Aug 20, 1890\

- The Waterloo Press (Indiana), Jun 24, 1926

- The Republic (Pennsylvania), Jun 24, 1926

- The South Bend Tribune, Jun, 4, 1926

- The Los Angeles Times, Aug 7, 1935

- The Post-Register (Idaho Falls), Aug 7, 1935

- The Boston Globe, Jan 5, 1947