Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:26 — 38.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

Can a person walk or run 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours, doing a mile in each and every hour for nearly 42 days? That was the strange question that surfaced in 1809 in England. In Part 1 of the 1000-milers I covered the attempts to reach 1,000 miles as fast possible. This part will cover what became known as the Barclay Match, walking a mile every hour, which was a feat of enduring sleep deprivation and altering sleep patterns dramatically. In a way, these matches were similar endurance activities to the bizarre walkathons of the 1930s that required participants to be on their feet every hour.

Critics of these 1,000-mile events called them “cruel exhibitions of self-torture” that had no point except to “win the empty applause of a thoughtless mob” and put a few pounds into the pockets of the walkers. They said, “there is nothing to learn from such exhibitions save they are positively injurious, physically and morally.” But others thought the matches gave “convincing proof that man is scarcely acquainted with his own capacity and powers.”

These “1,000 miles in 1,000 hours” events captivated the world, were cheered in person by tens of thousands of people, were wagered with the equivalent of millions of today’s value in dollars and launched the sport of pedestrianism into the public eye. It was first thought that this 1,000-mile feat was an impossibility, and it was called a “Herculean” effort. Betting was heavy and wagers were nearly always against success. But during a 100-year period, there were more than 200 attempts of this curious challenge and more than half were successes. How did this all begin?

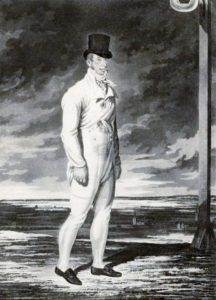

Captain Robert Barclay

Robert Barclay Allardice, or “Captain Barclay,” of Ury, Scotland, was born to a Scottish family in 1779. His father had been a member of Parliament and owned extensive estates. When young Barclay was fifteen years old, he won a 100 guineas wager, walking heal-toe six miles in one hour which at that time was considered a great accomplishment. When he was twenty years old, he covered 150 miles in two days, and in 1801, in very hot weather, he walked 300 miles in five days. Also, that year he walked/ran 110 miles in 19:27 in a muddy park. He became a very experienced walker who took on many wagers. He also was an officer in the army and thus called “Captain.”

Robert Barclay Allardice, or “Captain Barclay,” of Ury, Scotland, was born to a Scottish family in 1779. His father had been a member of Parliament and owned extensive estates. When young Barclay was fifteen years old, he won a 100 guineas wager, walking heal-toe six miles in one hour which at that time was considered a great accomplishment. When he was twenty years old, he covered 150 miles in two days, and in 1801, in very hot weather, he walked 300 miles in five days. Also, that year he walked/ran 110 miles in 19:27 in a muddy park. He became a very experienced walker who took on many wagers. He also was an officer in the army and thus called “Captain.”

In September 1808 Barley started to consider accepting a challenge to walk 1,000 miles in 1,000 consecutive hours for 1,000 guineas, a large fortune at that time. (Worth about $155,000 in 2019). For a farm laborer, a year’s wages were about 50 guineas.

Barclay first conducted a secret test at his estate in Scotland. One of his tenant farmers was able to walk one mile, every hour for eight days. Barclay decided to accept the 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours challenge.

Others had attempted this before, but no one went longer than 30 days. For example, in 1772 a tailor began a walk on a large wager to walk 1,000 mile in 1000 hours on “a spot of ground marked out for the purpose near Tyburn Turnpike” in London. It is believed that he was unsuccessful. A pedestrian named Jones sought to walk every hour for a month but quit in less than three weeks. Others were defeated by lack of sleep, swollen legs, and other various problems. A man from Gloucestershire rode a horse 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours, one mile in each hour, on Stinchcombe Hill in Dursley, England. “He won with ease.”

As word spread about this challenge, other 1000-mile ideas were spawned, including by George Wilson, who wanted to attempt walking 1,000 miles in less than half the time, in 20 hours. (See Part 1).

1,000 Miles in 1,000 Consecutive Hours

Months passed and Barclay’s challenge was put together to be performed on open land near Newmarket, England. A half mile course was laid out to be walked out and back in a straight line over smooth and even uncultivated land. Tent camps were constructed at each end for recorders and assistants.

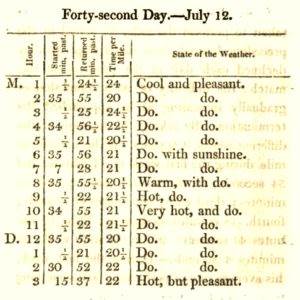

Barclay began the monotonous six-week task just after midnight of June 1, 1809. Seven gas lamps on poles 100 yards apart were lit each evening like streetlamps. He would generally start each mile about fifteen minutes before the finish of the first hour and then do the next mile at the top of the second hour. In that way he could take about a 90-minute rest before heading out again for the next two miles. Over the first three nights he overslept by a few minutes and had to really speed up his pace in order to finish an entire mile before the hour ended.

He dressed in a “jacket and breeches, and woolen stockings. His shoes appeared to be very large, and a handkerchief hung loosely about his neck.” He would usually have two men walking on each side of him, day and night. After each mile they signed their names into a log book, describing the weather and how he was feeling.

On his first day, his slowest mile was 16 minutes, and the average mile was 15:15. “He paced along at a sort of lounging gait without any apparent extraordinary exertions, scarcely raising his feet two inches above the ground.” He ate his first breakfast at 5 a.m. when he dined on roast fowl, drank a pint of strong ale and two cups of tea, with bread and butter. For the first few days he didn’t go to bed between walking stretches, and just reclined on a sofa or did a little strolling in Newmarket outside the course.

On his first day, his slowest mile was 16 minutes, and the average mile was 15:15. “He paced along at a sort of lounging gait without any apparent extraordinary exertions, scarcely raising his feet two inches above the ground.” He ate his first breakfast at 5 a.m. when he dined on roast fowl, drank a pint of strong ale and two cups of tea, with bread and butter. For the first few days he didn’t go to bed between walking stretches, and just reclined on a sofa or did a little strolling in Newmarket outside the course.

By the eighth day, Barclay had walked about 135 miles. Onlookers were curious to see if he was exhausted. He wasn’t, and appeared to be happy, with good health. At night he was able to fall asleep instantly and arose at the right time without any trouble.

At times he was greatly bothered by the dust. On day 10 he grew very tired because of the high wind and rain. On the 12th day he rested often, slept well, but complained about pain in his neck and shoulders. It was believed that he wasn’t wearing enough warm clothes at night. On the 13th day his calf muscles were seizing up and were very painful every time he started a new mile.

Barclay ate four meals a day, about every six hours. His diet generally consisted of cold beef steaks and mutton chops for a total of 5-6 pounds of meat each day. He also ate some vegetables and would drink about two bottles of port wine. For every mile, he added a few yards so that no one could cause a dispute. His mile times had slowed from about 15-minute-miles to 21-minute-miles.

Barclay ate four meals a day, about every six hours. His diet generally consisted of cold beef steaks and mutton chops for a total of 5-6 pounds of meat each day. He also ate some vegetables and would drink about two bottles of port wine. For every mile, he added a few yards so that no one could cause a dispute. His mile times had slowed from about 15-minute-miles to 21-minute-miles.

On the 16th day he moved to new lodgings near the “Horse and Jockey” pub, with a new course laid out on the Norwich Road. The change was good for him, and he felt more comfortable. His food was cooked outside. For some reason, his muscles were in the greatest pain around 3 a.m. each night. On the 19th morning he had difficulty walking and would lie down frequently to sleep, but his appetite continued to be very good. The next day his legs and feet were soaked in vinegar to take away soreness.

The weather was consistent for the first 20 days, with some rain about every day. After that, heat became the enemy of his walks for the second half of his long challenge, which hardened up the road. They used a “water cart” once a day to soften up the road and pound down the dust.

Crowds came to watch. It wasn’t just a sporting event; it was also a social event. They held picnics and ran races among themselves. Not everyone wanted him to succeed, especially those who were betting against him. Some gas lamps for the night were broken by rocks or shot by muskets. Barclay carried pistols on his waist belt and arranged for a bodyguard, John Gully, a former boxing champion.

By the 23rd day he had a terrible toothache, and he became feverish. It took two days for it to calm down. On day 25 he had great difficulty starting his miles. His attendants used remedies such as oil and camphor to rub down his painful muscles. The pain progressed down to his ankles and his legs became swollen. When heavy rain fell, he had to wear a heavier coat and his mile times increased to 36:30.

By the 23rd day he had a terrible toothache, and he became feverish. It took two days for it to calm down. On day 25 he had great difficulty starting his miles. His attendants used remedies such as oil and camphor to rub down his painful muscles. The pain progressed down to his ankles and his legs became swollen. When heavy rain fell, he had to wear a heavier coat and his mile times increased to 36:30.

On the 26th day he fell into a deep sleep state, and it was apparent he was still asleep as he began his 607th mile. His attendant, William Cross had to beat him on the shoulders with a walking stick in order to wake him up in time to complete his task within the hour.

On day 32, he needed help getting to his feet after resting. His mile times slowed to well over 30 minutes, making it too hard to get any rest. He soon had so much pain he kept crying out and “walked in a shuffling manner.” It was said, “His courage was unconquerable.” By day 35 he had doubts if he could continue because of spasms in his legs. But with a few days to go, he was very confident about succeeding. It was reported, “He declared he would die on the road rather than give in.”

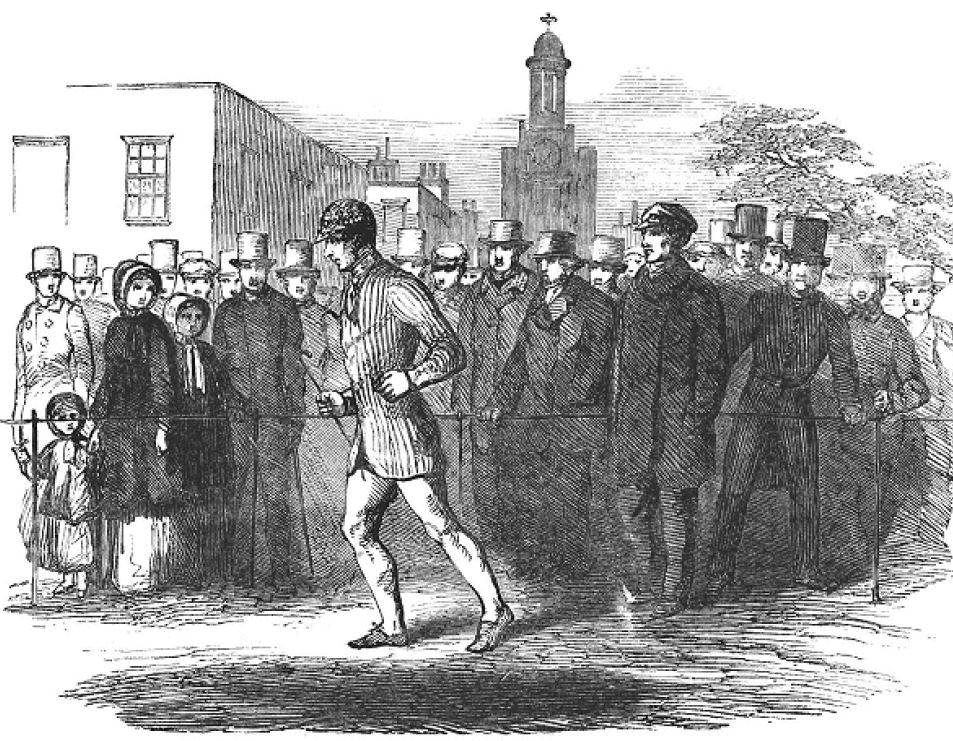

During the last two days of his long journey, he was in good spirits and completed his miles in shorter times than he had for many days. The weather was better, and he walked many hours without his large coat. The crowd of people during the concluding days had been “unprecedented.” No lodging could be found anywhere in the Newmarket area. The course became so crowded that Barclay was interrupted often and they finally had to rope off his walking area to keep it clear.

On the afternoon of the 42nd day he finished his last mile “with perfect ease and great spirits, amidst an immense concourse of spectators.” The crowd went wild. His bodyguard led the masses in three “rousing cheers.”

On the afternoon of the 42nd day he finished his last mile “with perfect ease and great spirits, amidst an immense concourse of spectators.” The crowd went wild. His bodyguard led the masses in three “rousing cheers.”

When he was asked what he planned to do now that it was over, he said he looked forward to taking a long, good sleep. But he said he would need to be awakened about three times during the night to transition into longer sleep. Right after finishing, he went and took a warm bath as the bells of Newmarket rang loudly. He won an enormous sum of about 16,000 guineas. All bets exceeded 100,000 guineas or about 8 million in 2019 dollars.

During the six weeks of walking, he lost about 32 pounds, weighing 154 pounds at the finish. His fastest mile was 12:00. This fastest walk time for 24 miles during a 24-hour day was 5:40 and his slowest was 8:39. Altogether his moving time on the course was 12 days, 8 hours for the 1,000 miles in 41.7 days.

Captain Robert Barclay died in 1854 as a result of injuries from being kicked by a horse.

Initial Unsuccessful Copycat Attempts

Captain Barclay had proven it could be done. The fame of Barclay’s accomplishment spread like wildfire. Similar to the 50-mile craze of 1963, a 1000-mile craze erupted instantly in 1809. Others tried to duplicate his accomplishment. It became known as a “Barclay Match.” History and been made. Some later called Barclay the “father of pedestrianism.”

Within a week of Barclay’s 1809 finish In Somerset, England, the first copycat was Mr. Howe, “a stout, athletic man,” took up the challenge for 300 guineas. with odds 10-1 against him. He walked over a piece of land from his own door at Cliffe Common. After twelve days he was still walking but “it was expected every hour that he would give in.” Howe quit after the 15th day and lost 200 guineas. It was reported that “his health was much injured.”

Another man, in Ireland, weighing 280 pounds took on a wager to accomplish the Barclay Match “to walk OVER a thousand miles in a thousand successive hours.” The betting odds were 50-1 against him. A report included, “The portly personage who was to be the hero in this extraordinary scene waddled forth to the race course. All eyes were eagerly fixed upon him and just as they thought he was about to start, he pulled out of his pocket a sheet of paper on which was written the words, ‘A Thousand Miles in a Thousand Successive Hours.’ He laid it on the ground, and then deliberately walked over it, to the astonishment and chagrin of the deluded beholders. A universal murmur was immediately set up at this hoax and many swore that they would not be ‘walked over’ in that kind of manner, but demanded their stakes be returned. It being the opinion of the umpires, however, that the wager was fairly won, the winner immediately pocketed the money and walked off.”

Many other attempts were made and failed. In 1811, A Mr. Blackie of Somershire made the attempt be had to quit after 23 days because of terrible swollen legs. He had lost nearly 50 pounds during his try. Others quite because of injured feet, pulled hamstrings. The newspapers seemed to delight in all these failures making Captain Barclays fame grow even more.

First Successful Copycat Barclay Match

In 1811 it was reported, but not widely know, that Thomas Standen, age 60, of Salehurst, England, successfully completed the Barclay Match at Newmarket and extended it to 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours. The event did not receive wide coverage or crowds. Why 1,100 miles? Many pedestrians want to “one-up” Barclay. They could not do it faster, but they could go further, and attempt variations that required their rest times to be shorter, and more frequent, pushing the limits of sleep deprivation.

1,100 Miles in 1,100 Hours

In 1815, Josiah Eaton, age 46, was a baker from Woodford, Northamptonshire, England. He was a small man, only 5’2”. He announced that he would attempt the Barclay Match but add more to it, and walk 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours, not realizing that Standen had already accomplished this extended feat four years before.

In 1815, Josiah Eaton, age 46, was a baker from Woodford, Northamptonshire, England. He was a small man, only 5’2”. He announced that he would attempt the Barclay Match but add more to it, and walk 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours, not realizing that Standen had already accomplished this extended feat four years before.

Eaton would walk at Blackheath, at the same location where George Wilson’s walk caused riots and Wilson arrest just a couple months earlier. (See Part 1). It is puzzling why Eaton selected the same county that was so unfriendly to Wilson’s walking stunt. He did not want the local magistrates to interfere with his walk as they did to Wilson, so he made it clear that he wasn’t walking for money and cancelled all his personal bets. But betting on or against Eaton certainly did take place and the people even bet on whether the magistrates would interfere with the walk.

There was a lot of skepticism whether he or anyone could duplicate or exceed what Barclay had accomplished. . It was said, “Captain Barclay was not only a man of great constitutional power, but he also knew how to train, whereas Eaton did not appear to possess the former, neither had he adopted the latter.”

Eaton started on November 10, 1815, near the Hare and Billet pub on a quarter mile course with two small red flags marking each end. He wore a white hat, blue coat, and striped waist coat. He did his sleeping in the pub. He used the same crew chief that Wilson used, a Mr. Stevenson. His first mile was accomplished in only 14 minutes. “A great concourse of persons assembled towards evening.” Like Barclay, he walked one mile at the end of the hour and another mile at the beginning of the next hour, giving him about 90 minutes of rest between his walking efforts.

As Eaton went along well, unsubstantiated rumors emerged that he wasn’t walking at night. To counter this, Eaton made a statement, “I will, for 100 guineas, give up the distance now performed, and commence again with the assertion of such malicious falsehood, if he will enter the lists against me.”

After ten days, a poem was published in the newspaper:

Since tramping now is all the rage

Some hundred daily take the stage

The walking man to greet on;

And oft impatient of delay,

From meals unfinished run away,

To Blackheath, there, to Eat-on

Why Eaton walks, it is not known very well,

‘Tis for Pedestrian glory some have said;

But other folks with much more reason tell,

This is the way the baker makes his bread!

By Christmas Eve, 6 p.m., Eaton had walked 1,062 miles. There were still rumors that Eaton had cheated. An affidavit was issued signed by four witnesses that Eaton had not cheated, that one of the four had always been on the course with him since he started on November 10th. Eaton also included his testimony in the affidavit.

By Christmas Eve, 6 p.m., Eaton had walked 1,062 miles. There were still rumors that Eaton had cheated. An affidavit was issued signed by four witnesses that Eaton had not cheated, that one of the four had always been on the course with him since he started on November 10th. Eaton also included his testimony in the affidavit.

Eaton successfully finished the Barclay Match plus 100 more miles on December 26, 1815. The Gentleman’s Magazine wrote, “The extraordinary task of pedestrianism which has just been completed by Josiah Eaton, has not only exceeded all former experiments of this nature, but given convincing proof that man is scarcely acquainted with his own capacity and powers.”

Within two weeks, Eaton was disappointed to discover that he had not been the first person to accomplish 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours. Because Eaton did not receive money for all his effort, he was still just a poor baker. Within a month he was in debtor’s prison for not being able to pay a debt.

1,000 Miles in 1,000 Hours at the Top of Each Hour

After release from prison, Josiah Eaton organized another 1,100 x 1,100, again at Blackheath starting on June 10, 1816. This time he would be required to start each mile at the top of the hour, which would be much harder, only getting about 45 minutes consecutive rest. Also, all his miles were required to be walked within 20 minutes. The betting odds were “greatly against him.”

Early on Eaton had feet problems and then had swollen legs, but he was in good spirits, and he quickly adapted his sleep patterns to cat naps. He could quickly fall asleep and was easily awakened by his attendants. Odds were in his favor when he reached 925 miles. It had not been easy, as opponents made attempts to obstruct him.

With about 75 miles to go, Eaton injured his ankle which forced him to use two walking sticks for a while. The last mile finally arrived. It was reported, “Eaton in performing the last mile, was attempted to be thrown three times by some supposed hirelings of his opponents.” But he successfully completed 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours on July 20, 1816 in front of an “immense crowd” after nearly 46 days of walking every hour. After winning the match, he went another mile in just 12 minutes. “At the conclusion of his performance, the air rang with acclamations, and partaking of some refreshment.”

He was soon offered a wager for 1,000 guineas to walk 100 yards every 15 minutes for 1,000 hours. He didn’t take that bet.

2,000 Half Miles in 2,000 Half Hours (1 Mile Each Hour)

Later in 1816, Eaton’s friends accepted a wager of 500 guineas that he could walk 2,000 half miles in 2,000 successive half hours. This would involve only getting about 22 minutes of rest each half hour, requiring an outrageous sleep pattern for nearly 42 days.

Eaton started on October 23, 1816, walking on a course about three miles from Croydon, England on the Brixton Causeway. He walked on a quarter-mile out-and-back path near a private home where he took his rests. Umpires were always on hand to witness the effort. Within a couple days, a Mr. Petty Sessions was trying to get magistrates to stop the match because of the inconvenience it was causing locally from the crowds coming to watch. Within ten days, the newspaper was calling Eaton the “Sleep Walker.” It was said, “he frequently takes a few winks during walking, and only requires, it is said, a gentle shake from his attendant to render him awake to what he has to perform.”

By the time he was halfway, skepticism had mostly gone away, and betting was in his favor. As he was getting close to reaching the 2,000 half miles he issued a shocking statement, “I feel myself fully competent to complete the task I have undertaken, of walking 2,000 half miles in 2,000 successive half hours, which would have been finished on the 5th of December at noon; but being deceived by the gentlemen who should have supported me, I am determined not to complete the task. I therefore hereby give notice, I shall walk only until 11:00 on Thursday, December 5, 1816, being only 1,998 half miles, and recommend all parties to consider their bets to be null and void.”

By the time he was halfway, skepticism had mostly gone away, and betting was in his favor. As he was getting close to reaching the 2,000 half miles he issued a shocking statement, “I feel myself fully competent to complete the task I have undertaken, of walking 2,000 half miles in 2,000 successive half hours, which would have been finished on the 5th of December at noon; but being deceived by the gentlemen who should have supported me, I am determined not to complete the task. I therefore hereby give notice, I shall walk only until 11:00 on Thursday, December 5, 1816, being only 1,998 half miles, and recommend all parties to consider their bets to be null and void.”

The problem was that Eaton had been promised money from several men if he accomplished the task, but as he neared the finish, he discovered that they were not going to follow through. He was told that the primary person had died and that the bet was void. Eaton realized that he had been duped, that actually no serious bet had been made. He stopped as he promised with one mile to go, walking his last half mile freshly in 8:30. He claimed he did not receive even a shilling from the pub owner. In all he only received 25 guineas which didn’t come close to covering his expenses. Despite the halt, his 1998 x 1998 half-mile effort was declared, “the greatest pedestrian feat ever performed.”

4,032 Quarter Miles in 4,032 Quarter Hours (1 Mile Each Hour)

Now it started to become truly stupid. In 1818 Eaton started an attempt to walk a quarter mile every 15 minutes for six weeks (4,032 quarter miles) in Stowmarket, Suffolk, England. Betting was 5 to 1 against him. He began his outrageous attempt across from the Pot of Flowers Inn on May 11, 1818. After each quarter mile, Eaton would ring a bell. Wet weather affected his performance early on, making him very tired and lame but he recovered and soon bets were close to even money.

It was reported, “He falls asleep immediately on throwing himself on his bed, which is placed in a hut at the end of his ground and awakes at the slightest touch or call.” Hot weather arrived and caused problems, but he continued to push forward. Eaton was successful and finished on June 30, 1818. He was paraded through the streets of Stowmarket in front of a crowd of 2,000 people.

It was reported, “He falls asleep immediately on throwing himself on his bed, which is placed in a hut at the end of his ground and awakes at the slightest touch or call.” Hot weather arrived and caused problems, but he continued to push forward. Eaton was successful and finished on June 30, 1818. He was paraded through the streets of Stowmarket in front of a crowd of 2,000 people.

1,000 Miles in 667 Hours (1.5 Miles Each Hour)

Yet another flavor of the Barclay Match took place in September, 1816. N. B. Barnet, age 72, started a 1,500-mile attempt in 32 days on a course at the Mitre Tavern, Lower Tooting, Surry. He was successful with 45 minutes to spare. Along the way he achieved 1,000 miles by doing 1.5 miles every hour, starting at the first of every hour!

A report included, “For the last five or six miles he was accompanied by a large concourse of person, male and female, on horseback and on foot, who were anxious to witness of his pedestrian power. At the end of the last mile, he was received with shouts of applause by his friends at the Mitre; and after he had refreshed himself, they seated him in a triumphal car and bore him in grand procession through Lower and Upper Tooting, the village musicians, two fiddlers and a tambourine player, accompanying him in his progress with the very appropriate air, ‘See The Conquering Hero comes.’”

1,200 Miles in 1,200 Hours (1 Mile Each Hour)

Robert Skipper worked as a “ostler” (took care of horses) at an Inn in Norwich, England and had also served in the army for up to 15 years. He took on attempts to walk 1,000 miles in 20 hours but failed each time, once because of injury and the other time because magistrates halted the attempt. In 1822 he took on an extended Barclay Match to walk 1,200 Miles in 1,200 Hours. His feat was accomplished near Papermills Turnpike, Cambridge, England. After finishing, he immediately for fun, walked six miles within the next hour.

Robert Skipper worked as a “ostler” (took care of horses) at an Inn in Norwich, England and had also served in the army for up to 15 years. He took on attempts to walk 1,000 miles in 20 hours but failed each time, once because of injury and the other time because magistrates halted the attempt. In 1822 he took on an extended Barclay Match to walk 1,200 Miles in 1,200 Hours. His feat was accomplished near Papermills Turnpike, Cambridge, England. After finishing, he immediately for fun, walked six miles within the next hour.

1,000 Miles in 1,000 half hours. (2 Miles Each Hour)

A few months later, also in 1822, Robert Skipper was back at it, this time to do 1,000 miles in 1,000 half hours. He began on Sept 25, 1822 next to cricket grounds (Prussia Gardens) on a turnpike road going from Newmarket to Norwich. It was reported, “He is going on well at present, and excites great attention. He performs his task on the public road, half a mile out and half a mile in.” The betting odds were against him.

He was successful. Thousands were on hand to witness the finish including many Dukes and Lords. When he finally was able to sleep solid for five hours after finishing it made him pretty ill because he body couldn’t adjust fast to continuous sleep. He did not come away rich because no bets were involved. He only collected rewards from generous supporters.

1,250 Miles in 1,000 Hours (1.25 Miles each Hour)

In July 1838 J. E. Molloy, about age 30, successfully completed walking 1,250 miles in 1000 hours, walking 1.25 miles every hour at Bromley Common. It took its toll. “He appeared greatly fatigued, and seemed much swollen, particularly about the legs and feet, from want of proper rest.” He did it without drinking any drink stronger than tea or coffee.

As if that wasn’t enough for him, or perhaps the money he received pushed him to want more, just six weeks later he started on a quest to reach 1,000 miles in 500 hours, walking a mile every half hour seeking 500 guineas. The betting odds were heavily against him. His course was at Hall’s cricket ground in Camberwell, England. He would do a mile at the end of a half hour, rest two minutes and start his next mile at the start of the next half hour. Early on he averaged 13-minute miles. That gave him 32 consecutive minutes rest each hour. It was said that if he was successful, it would be the “greatest pedestrian feat on record.”

On day three, Molloy slipped and fell going up the steps leading to his room and badly bruised his leg but was able to continued. By day six he had severe pain in that leg and a surgeon was fetched who treated him with lotion. In a few hours he was better, in high spirits, but walked with a limp. Later that day when he reached mile 278, he had to quit and his wager was lost.

1,750 Miles in 1,000 Hours

In August, 1938, Charles Harris, a 14-year pedestrian veteran, walked 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours (1.5 miles each hour) in Finchley, England. A couple months later, he attempted another 42 days of walking to go 1,750 miles in 1,000 hours (1.75 miles each hour) at Battersea Fields in London. His method was to walk 3.5 miles each session which he would begin a about 38 minutes past the hour, giving him 22 minutes before starting the next 1.75 miles at the top of the hour. This would give him about 1:15 continuous rest every two hours. On weekends large numbers of spectators came to witness.

After 400 miles his spirits were good but he was struggling. His diet was roast beef, bread, and coffee. He would drink each day a pint of diluted brandy. Harris talked about his sleeping pattern and explained “that he always feels the first two weeks of any pedestrian undertaking to be the most arduous for want of deep slumber, which he never obtains.” He had to walk through terrible storm with high winds and penetrating rain showers that “sadly annoyed him.” He had come prepared to battle the elements but the storms were far more severe than he planned. Bets were against him.

At 1,464 miles Harris was still in good spirits but it was reported his “physical energies were beginning to fail. He no longer walked with a firm and vigorous step.” During rains, he caught a bad cold and was coughing violently. He had terrible sores and blisters on his feet and was limping. His sleeping patterns were poor, getting very little sleep. But betting had shifted in his favor and he hoped to receive about 100 pounds.

During his final weekend, Battersea Fields, along the Thames River was packed with about 6,000 people trying to get glimpse of Harris walking. He successfully completed the feat on December 3, 1838. He received “warm congratulations” and his friend paraded him around on a chair led by flags and a band playing music. Harris explained that the next week would be very rough because he always suffered from terrible pain after concluding those long walks, even worse pain than during the walk.

Two years later, Harris was arrested during another long walk (48 miles in six hours between two towns) which attracted huge crowds and was “an obstruction to passengers” on the road. He was accused of striking a man who tried to stop his progress. A constable came and hauled him away to the police station. His accuser never showed up and he was discharged.

1,000 Quarter Miles in 1,000 Quarter Hours, 1,000 Half Miles in 1,000 Half Hours, and 1,000 Miles in 1,000 Hours (1,750 Total Miles in 1,750 Hours)

Richard Manks “the Warwickshire Antelope” was born in 1818 during the first decade of the Barclay Match craze. He became a professional pedestrian in 1843 and accomplished his first 1000 x 1000 in 1850. In 1851 things got pretty ridiculous as he took on a challenge to do three consecutive matches, 1,000 quarter miles in 1,000 quarter hours, 1,000 half miles in 1,000 half hours, and then the traditional Barclay Match of 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours for a total of 1,750 miles in nearly 73 days!

Richard Manks “the Warwickshire Antelope” was born in 1818 during the first decade of the Barclay Match craze. He became a professional pedestrian in 1843 and accomplished his first 1000 x 1000 in 1850. In 1851 things got pretty ridiculous as he took on a challenge to do three consecutive matches, 1,000 quarter miles in 1,000 quarter hours, 1,000 half miles in 1,000 half hours, and then the traditional Barclay Match of 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours for a total of 1,750 miles in nearly 73 days!

The bizarre sleep deprivation challenge was held at Barrack Tavern Grounds at Sheffield, England. He started on June 23, 1851, waving to a large crowd. His bedroom was twelve yards from his course. Watchers were hired in eight-hour shifts to make sure he indeed walked and to keep time. Thousands of spectators would come to watch. He completed his 1,000 quarter miles on July 4, then rested only 12 minutes and started his half miles. He had already lost 25 pounds.

The newspaper recorded, “When aroused from his bed, though staggering, he persisted in going his rounds, although it required two men to be with and followed to steer him in his course, and keep him awake.” His roughest times were typically during the late afternoon when it was warmest and the from midnight to 4 a.m. “During those hours it is with the greatest difficulty Manks can be brought to a state of recollection and to convince him as to what he has to do, where to go, and when he has finished his half mile.” Manks declared that he would succeed or die. The local paper believed he was walking himself to death.

On July 25th he finished his half-mile challenge, and at 3 a.m. start his first full mile. Halfway through, a government doctor came to examine him and found his pulse rate to be 92 beats per minute. The doctor “declared him to be one of the most extraordinary men, for endurance and perseverance it had ever been his lot to meet with.”

As he neared 1,750 miles, it was estimated that nearly 160,000 people had come to watch him during the previous few days. He wowed the crowd by doing a 7:56 mile and racing against other pedestrians who came to visit. During the day he averaged about 12-minute miles and at night about 16-minute miles. On one of his last days, he was so disoriented that he walked into a wall cause bruises from head to knee. On his final mile the shouts and the applause of the massive crowd could be heard from far away. The newspaper declared, “Thus was finished the greatest feat ever contemplated by man.”

2,000 Miles in 2000 Half Hours (Two Miles each Hour)

James Searles of Leeds, England, was born in 1819. He was called “The Wonder” and was an experienced Barclay Match walker. He was referred to as a “champion” Pedestrian and had only lost three wagered walking matches out of about one hundred of all types. He was a man of small stature, only 5 feet 4 ½ inches in height but very muscular.

Searles, a rival of Richard Manks, first accomplished 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours at Tranmere near Liverpool in 1850, starting each mile at the top of the hour. In 1851 he accomplished 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours at the Old Red House at Battersea Fields in London. During his 735th mile, a young child ran under the ropes of his course and suddenly appeared at his feet. Searles had to spring to the side to avoid hurting the child and sprained his ankle. It swelled up badly and he had to do many miles on crutches. He prevailed and finished the match. He then immediately continued and accomplished 1,000 half-miles in 1,000 half hours, and 1,000 quarter miles in 1,000 quarter hours for 1,750 total miles in 1,750 hours duplicating what Richard Marks had already accomplished but Searles did it in a much harder reverse order. Thousands came to the grounds to watch on weekends.

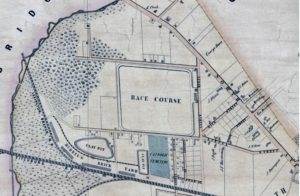

On September 20, 1852, Searles began his attempt to walk 2,000 miles in 2,000 half hours on a round track that involved seven laps to a mile near the Pineapple Inn, at Toxteth Park in Liverpool, England. During the first week it was reported, “One astonishing feature in connection with the pedestrian is, that he rises from his bed at the fixed time without requiring any person to rouse him, and starts on his journey apparently quite refreshed.”

Searles ate about eight pounds of “animal food” per day and was assisted by his father. He probably wasn’t taking in enough calories. By 500 miles he had lost 10 pounds. He had continued to lose weight at 1,000 miles. One Sunday he allowed a young man to race him during a mile. He really pressed the speed and accomplished his mile in less than ten minutes. The crowds were very large and promoters raised admission on Sundays. Searles perhaps was an early adopter of the ultramarathon belt buckle. On his belt he wore “three representation in silver, illustrative of his performances.”

As the finishing days approached, Searles was bothered by a badly sore knee, but was still pushing forward. He said he would finish if he had to walk on crutches. He complained of dizziness during his night but recovered during the days. One night a man wanted to see if Searles was really still walking. He climbed to the top of a railing surrounding the grounds and fell over into a pond. Searles, walking at the time, heard the splash in the dark and rushed to helped the man get out of the pond. He won over his skeptical spy who said Searles was “the cleverest man in Europe.”

He finished on November 1, 1852 and had lost nearly 30 pounds along the way. He walked his last mile in 7:30 and “looked tolerably well.” He wore new clothes and his champion belt. The band played “See the conquering hero comes.” It was said, “The match my be considered one of the most extraordinary ever recorded in the annals of pedestrianism.” That evening at a benefit held for him he danced a clog hornpipe.

1852 Barclay Match Frenzy

Manks and Searles help spark a Barclay Match Frenzy in 1852. The public started to get rather skeptical in recent years if these matches were being conducted fairly. It was written, “Deception has been often practiced by persons engaging to accomplish the distance in the time named, and, with the collusion of others, the cheat may be easily played off.” Some were charades to attract spectators that were charged entrance to watch the walker performed in enclosed areas. Some walkers in these enclosed area had been accused of stopping during nights.

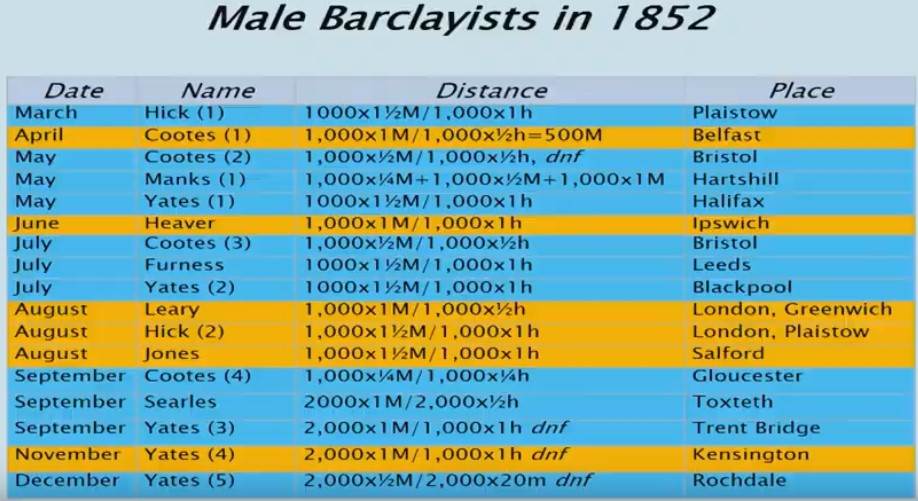

In 2018, Derek Martin collected and recorded the known “Male Barclayists”in 1852.

1,500 Miles in 1,000 Hours

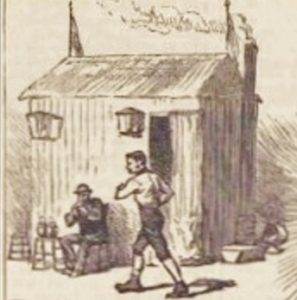

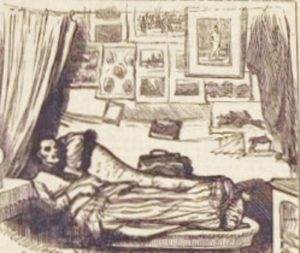

In 1877 at Lillie Bridge, William Gale, age 52 attempted 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours with each 1.5 mile started at the top of each hour, limiting him to no more than 37 minutes of continuous sleep for nearly six weeks. Thomas Hicks, of Leeds made a similar accomplishment back in 1852 at Royal Oak Grounds in Canning Town. Gale walked 36 miles per day and up to 8,000 paying spectators would come to watch each day. He walked a quarter-mile track and a large hut was constructed for his quarters. It contained a small stove, couch, “presenting the strange mixture of a doctor’s shop, bed-room, and kitchen. Opposite this hut is the head-quarters of the judges, in front of which a large clock is fixed.” During the night the grounds were open and free to spectators to all could see for themselves that he was still walking.

In 1877 at Lillie Bridge, William Gale, age 52 attempted 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours with each 1.5 mile started at the top of each hour, limiting him to no more than 37 minutes of continuous sleep for nearly six weeks. Thomas Hicks, of Leeds made a similar accomplishment back in 1852 at Royal Oak Grounds in Canning Town. Gale walked 36 miles per day and up to 8,000 paying spectators would come to watch each day. He walked a quarter-mile track and a large hut was constructed for his quarters. It contained a small stove, couch, “presenting the strange mixture of a doctor’s shop, bed-room, and kitchen. Opposite this hut is the head-quarters of the judges, in front of which a large clock is fixed.” During the night the grounds were open and free to spectators to all could see for themselves that he was still walking.

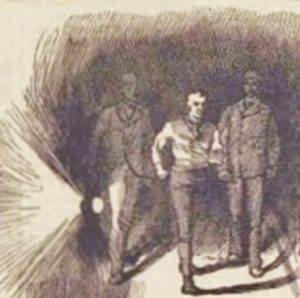

Gale really struggled with bad pain behind his knee and he became very depressed. A detailed report included, “Exactly at 1 1/2 minutes to each hour one of the judges appears on the balcony of the judges’ stand and rings a small hand-bell to announce to the attendant that the time has come to once again arouse the weary and exhausted man. Almost invariably the wiry little man appears up to time and often steps from his hut door at the very instant that the deep boom of Big Ben can be heard in the distance. A procession is then formed consisting always of the attendant carrying a lantern, one of the judges, who are bound to walk with him and generally two or three more whom curiosity or duty have determined to ‘make a night of it.’ The procession, with its steady and silent tramp, lit by the lantern, goes on. Each lap (for going to the mile) is called by the walking judge on duty, and duly echoed by the assistant judge in the box, who records the same in a book. And thus the weary hours of night pass.”

Gale really struggled with bad pain behind his knee and he became very depressed. A detailed report included, “Exactly at 1 1/2 minutes to each hour one of the judges appears on the balcony of the judges’ stand and rings a small hand-bell to announce to the attendant that the time has come to once again arouse the weary and exhausted man. Almost invariably the wiry little man appears up to time and often steps from his hut door at the very instant that the deep boom of Big Ben can be heard in the distance. A procession is then formed consisting always of the attendant carrying a lantern, one of the judges, who are bound to walk with him and generally two or three more whom curiosity or duty have determined to ‘make a night of it.’ The procession, with its steady and silent tramp, lit by the lantern, goes on. Each lap (for going to the mile) is called by the walking judge on duty, and duly echoed by the assistant judge in the box, who records the same in a book. And thus the weary hours of night pass.”

“Gradually the day breaks, the lanterns dispensed with and Gale seems fresher. In time the judges are relived and Gale takes his cold bath, the effect of which at times seems simply miraculous and in the early walk after it influence Gale seems to be another man to the one who but two hours before had plodded round with haggard look and shaking knees.”

With a few days to go Gale had so much pain in his leg that he didn’t sleep for more than 48 hours but he pushed ahead. On October 6, 1877, Gale successfully reached mile 1,500 accomplishing what was said to be”the most extraordinary walking feat ever attempted.”

4,000 Quarter Miles in 4,000 Periods of 10 Minutes (1,000 Miles in 667 Hours)

Also, in 1877 William Gale twice accomplished the most terrible sleep deprived Barclay Match, going 1,000 miles in 667 hours, by doing a quarter mile every ten minutes. He did this twice in 1877, once at the Canton Hotel Grounds at Cardiff, England and another time at the Agricultural Hall in London.

Gale started walking about 3:30 quarter miles. He soon suffered from terrible headaches, congested ears, and pained legs. But by the second week his sleep patterns had adjusted and he could sleep comfortably for about four-five minutes between his walks. He would fall asleep at once in a sitting position and woke up instantly on being touched. For each 24-hour period he slept about a total of 3-4 hours. Sometimes he didn’t know where he was. He thought he was out in the country in a farmyard. He could only recognize the dark line of the track before him. During the third week he was so constipated that his pulse was low and he became very week. Castor oil solved that problem. More than 10,000 people came to watch him reach his 1,000th mile. He walked his last quarter mile in 2:04.

There was harsh criticism in the newspapers about his accomplishment. “Gale’s walk of 1,000 miles was a disgusting as well as cruel exhibition of self-torture. He accomplished his task, and may claim the barren honour of having done more than any other pedestrian, but no one would be surprised to hear that the unnatural strain which he put upon himself had brought him to a premature grave. For four weeks this man has been walking with an interval every ten minutes of five or six minutes rest. Toward the end of his weary and bootless tramp he had to walk in a semi-somnolent state, and on one occasion he stood still, fast asleep. He had to be continually roused and urged on. He has walked his 4,000 quarter-miles in 4,000 successive ten minutes, but what does it amount to. At the best he has won the empty applause of a thoughtless mob, and put a few pounds into his pocket. There is nothing to learn from such exhibitions save they are positively injurious, physically and morally.”

Woman Barclayists

Woman also attempted and achieved the Barclay Match and perhaps more than men. But their achievements were rarely covered widely as compared to the men. Women were not allowed to do walking events in many venues and thus most were conducted in more private settings. In 2018 Derek Martin gave a presentation on Barclay Matches from 1809-1902. He estimated that there were at least 118 women who attempted, completed, or claimed to have completed a Barclay Match of some flavor between 1809 and 1908.

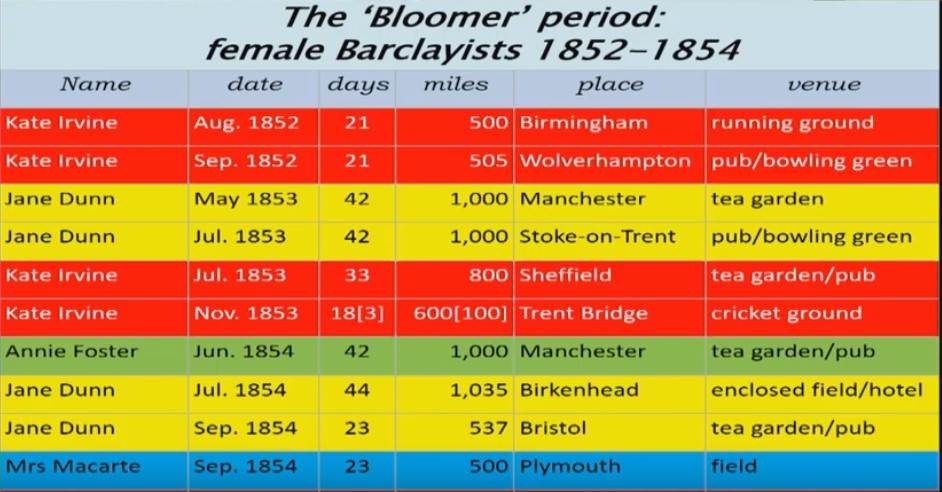

In 1844, the first known woman walked 1000 miles in 1000 hours. She was Mrs. Harrison, age 50, who walked on the Leeds and Whitehall Road. From 1852 to 1854 a few women started to take on the challenge wearing bloomers, perhaps sparked by American Katie Irvine who went to England and made attempts. Jane Dunn and Annie Foster were successful in covering the entire 1,000 miles.

Emma Sharp

From 1864-1866 more women took up the Barclay Match getting increased attention and was triggered by Emma Sharp and Margaret Douglas.

From 1864-1866 more women took up the Barclay Match getting increased attention and was triggered by Emma Sharp and Margaret Douglas.

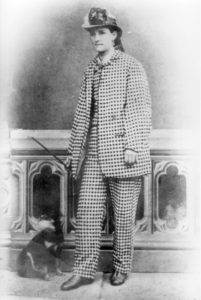

One of the most widely covered walk by a woman was accomplished by Emma Sharp, age 30, of Bowling, England who started her walk on September 17, 1864 at Bradford, England near a pub, the Quarry Gap Hotel. She chose to be sensible and dressed like a man. It was written that “almost the only indication of her sex being in her large drooping straw hat which was ornamented with a white feather and other feminine adornments.” She carried a stick in her right hand.

She used a roped-off 120 yard course and walked a mile at the end of an hour and another at the top of the next hour. For the two miles, she would walk 14 laps + 80 yards to and from her room. Unlike other attempts by women, thousands came out to watch and made bets. Early on she suffered from swollen ankles by they became stronger as she went along.

As occurred to many of the men walkers, shady characters attempted to stop her. She was attacked with chloroform, burning embers were thrown on her, some attempted to drug her food, and others tried to trip her. During the final days, eighteen police officers, not in uniform, disguised as civilians watched over her and attempted to catch these criminals. One friend walked in front of her with a loaded rifle at night. Emma finally walked the last two days carrying a pistol which many times she would fire in the air as a warning.

Sharp finished successfully her 1,000 x 1,000 on October 29, 1864 in front of thousands of spectators. A band played and an ox was roasted in her honor. Her husband had been embarrassed with her man-like efforts and stayed out of public view. But once he realized how much money she won, he quit his job and started his own business.

The Barclay Match in America

The Barclay Match eventually made its way to America in 1842. Captain Thomas Ellsworth “the St. Louis Pedestrian” accomplished the first ever American Barclay Match near Boston, Massachusetts at the one-mile Cambridge Trotting Course near Porter’s hotel. At mile 500 it was reported that he was in good spirit and he thought he could “ go through with the feat with ease.” He went on to finish. In 1843 he Ellsworth competed against a Mr. Fogg or Brown at the 1,000 x 1,000 on a course at Chelsea, Massachusetts. Ellsworth finished. He attempted it again in May, 1845 in New Orleans, Louisiana on the “Eclipse Course.” By mile 792 his legs were very swollen with severe pain. For many days he had to battle walking in almost incessant rains. When the sun was out it was terribly hot and humid. Three men were hired as watchers and had to swear in front of a judge with threats of perjury charges that they would report on his success or failure. Ellsworth went on to finish his third successful 1000 x 1000. For the fourth time he went the distance in 1851 at St. Louis, Missouri for $1,000 ($33,000 value in 2019). He then set off immediately to walk 500 miles in 250 hours. In 1855 he did it again for the 5th time in Sacramento, California. He became the most prolific Barclay Match walker in American history.

Other Americans completed the match in those early years. In 1846 George Clarke did it at Norwich, New York. In 1852, A Mr. Kelley completed the match in Sacramento, California. in 1857. James Lambert, age 21, of England went to Boston to attempt the feat in Stewart’s Gymnasium for $1,000. He started on July 28th. In his final days he was in a terrible stupor and it was very hard to make him up each time to walk his mile which he would stagger through. But he succeeded walking his last mile in a slow 20 minutes in front of a huge crowd. He ended up getting $2,000 for his efforts. While that was happening, an C. A. Wesson, an American also was doing the match at Lockport, New York, finishing it a couple weeks later. At Waukegan, Illinois, also in 1878, a Mr. Burtis walked 1,000 miles, two per hour, at Case’s Warehouse. A track three-feet wide was constructed, raised 1-2 inches and filled in with saw dust. It took 26 laps in circles to make one mile, so he went 26,000 laps. His last miles was the fastest of his journey.

Daniel O’Leary’s 1,000 Miles in 1,000 Hours

The match that received the most attention in America was performed by the very famous American pedestrian, Daniel O’Leary, age 63, took on the challenge on September 8, 1907 at Norwood Inn, in Norwood, Ohio, near Cincinnati. The mayor for Norwood walked the first mile with O’Leary. A Miss Pauline Holscher was going along too on roller skates, doing two miles to his one. The walk was initiated by the International Tuberculosis Association. Doctors were very curious about this attempt and didn’t think it could be done, not realizing that dozens had accomplished it in years past. O’Leary was also claiming this would be a record of some sort but it would not be.

The match that received the most attention in America was performed by the very famous American pedestrian, Daniel O’Leary, age 63, took on the challenge on September 8, 1907 at Norwood Inn, in Norwood, Ohio, near Cincinnati. The mayor for Norwood walked the first mile with O’Leary. A Miss Pauline Holscher was going along too on roller skates, doing two miles to his one. The walk was initiated by the International Tuberculosis Association. Doctors were very curious about this attempt and didn’t think it could be done, not realizing that dozens had accomplished it in years past. O’Leary was also claiming this would be a record of some sort but it would not be.

O’Leary walked each mile at the top of each hour. After 200 miles he was not “showing the least sign of the strain.” But soon the mental strain of it all affected him. As he started his 3rd week, 5,000 people came to watch on that Sunday. At mile 600 he was described as being “haggered” and “showing signs of tremendous strain on his nervous system.” Doctors advised that he take a little bit of stimulants. As the miles continued, O’Leary suffered from a sore left foot and caught a cold from the damp nights and he suffered from bad nose bleeds. At mile 925 the doctors pronounced him in “first-class condition” considering all the miles he had walked.

Thousands came out to watch his final day. A “walking carnival” was held including a lady’s walking contest, a ten-mile relay walk, and a free-for-all boys walk. At the finish O’Leary said he felt all right and only lost 14 pounds. He won $5,000 and the gate receipts “were considerable.”

O’Leary issued a statement that included, “Although I have been congratulated for doing something extraordinary, I wish to say that I did not go into the thing seeking any cheap advertising or looking for future glory. When it was suggested that it would be next to impossible for any man to walk 1,000 miles in 1,000 consecutive hours, I made up my mind that I would do the trick.”

The Barclay Match in the Modern Era

Eventually the Barclay match was condemned by many and died out. In the modern era of ultrarunning, others have completed the Barclay Match successfully. It reappeared in the late 1980s in Australia when Ron Grant and Trevor Harris began outdoing one another going distances far further than 1,000 miles Grant eventually managed to do 1.86 miles each hour for 1,000 hours. Two years later Craig Rowe exceeded this with 1.96 miles each hour for 1,000 hours.

The Flora 1,000 Mile Challenge

In 2003 four men and two women took on the traditional Barclay Match at the Flora 1,000 Mile Challenge starting at Blackheath Common in England. Never before had so many attempted it simultaneously in a competition. They were: Paul Selby, David Lake, Lloyd Scott, Rory Coleman, Sharon Gayter and Shona Crombie-Hicks. Medical experts predicted that the strain would cause “delusion and mental exhaustion.”

In 2003 four men and two women took on the traditional Barclay Match at the Flora 1,000 Mile Challenge starting at Blackheath Common in England. Never before had so many attempted it simultaneously in a competition. They were: Paul Selby, David Lake, Lloyd Scott, Rory Coleman, Sharon Gayter and Shona Crombie-Hicks. Medical experts predicted that the strain would cause “delusion and mental exhaustion.”

The event was started on March 2, 2003 by Prince Andrew and competitors went from place to to place on the London Marathon route shuttled by a bus each day. They walked or ran and were paid about minimum wage for each hour, 6.75 pounds.

They lived in a bus 24/7 for nearly six weeks. It was a coach similar to the kind used by touring rock bands. They ran two miles at a time at the bottom and top of each hour as Barclay did nearly 200 years earlier. Scott dropped out after 335 miles. On one day Gayter took a wrong turn and had to run a six-minute-mile in order to return to the bus before the hour was finished. Five finished, and then they all headed out to run the London Marathon. Crombie-Hicks finished the marathon with a time of 3:08 winning 3,000 pounds.

Perhaps after reading this, more will give it a try. Good luck.

Sources:

- Peter Radford, The Celebrated Captain Barclay: Sport, Gambling and Adventure in Regency Times.

- Andy Milroy, “The History of the 1,000 Mile Race”

- P. S. Marshall: Richard Manks and the Pedestrians

- Walking 1100 Miles in 1100 Hours

- Derek Martin “A Short History of the Barclay Match: 1809-1909”

- The Ipswich Journal (England), Jul 22, 1809, Oct 1, 1808, Nov 5, 1808

- The Observer (London), Oct 30, 1808

- The Morning Post (London), Jun 5, Dec 27, 1808

- The Bury and Norwich Post (England) Dec 21, 1808

- The Lancaster Gazette (England), Jul 22, 1809

- The Evening Post (New York), Sep 19, 1809

- The Freeman’s Journal (Ireland), Aug 16, 1809, Aug 19, 1813

- Hampshire Telegraph and Navel Chronicle (England), Jul 31, 1809

- The Caledonian Mercury (Scotland), Aug 25, 1814

- The Exeter Flying Post (England), Nov 16, 1815

- The Champion and Weekly Herald (England), Nov 4, 1838

- The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser, Dec 1, 1838

- Jackson’s Oxford Journal, Oct 27, 1838

- Brooklyn Evening Star, Aug 26, 1842

- New York Daily Herald, Jun 1, 1845

- The Times-Picayune (Louisiana) Apr 20, 1845

- Buffalo Morning Express, Jul 25, 1846

- The Weekly Standard and Express (Blackburn, England) Dec 12, 1838

- The Era (London, England), Aug 3, 24, 1851

- The Portsmouth Inquirer (Ohio), Nov 7, 1851

- Liverpool Mercury, Sep 24, Oct 12,19, 29, Nov 2, 1852, 21 Sep 1864

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sep 10, 1857

- Buffalo Courier, Sept 27, 1858

- The Leeds Mercury, 20 Nov 1877

- The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, (England) 17 Nov 1877

- The Marion Star (Ohio), Sep 7, Oct 19, 1907

- The Cincinnati Enquirer, Sep 23, Oct 22, 1907

- The Dayton Herald (Oho), Oct 17, 1907

- The Sun (New York), Oct 21, 1907

- Harrisburg Telegraph, Nov 13, 1946

- The Observer (London), April 13, 2003

- The Guardian (London), Apr 7, 2003