Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:42 — 19.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

Both a podcast and a full article

Prior to the 1960s, most of the ultrarunners participating in ultradistance races were professionals. It was a spectator sport. The general public never had serious thoughts that they too could run ultradistances.

Prior to the 1960s, most of the ultrarunners participating in ultradistance races were professionals. It was a spectator sport. The general public never had serious thoughts that they too could run ultradistances.

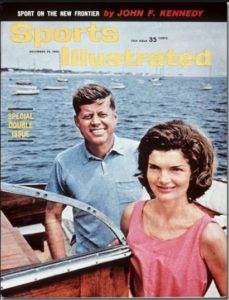

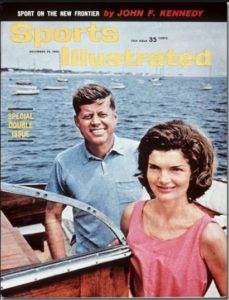

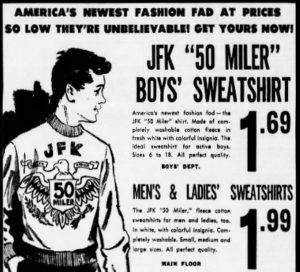

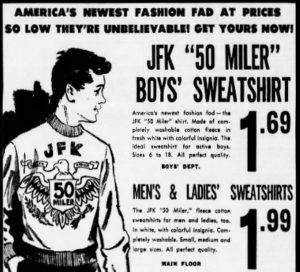

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy unintentionally played a key role that provided the spark to ignite interest for ultrarunning in America and elsewhere. The door was flung open for all who wanted to challenge themselves. An unexpected 50-mile frenzy swept across the U.S. like a raging fire that dominated the newspapers for weeks. Tens of thousands of people attempted to hike 50 miles, both the old and the very young. Virtually unnoticed was a small club event run/hiked by high school boys in Maryland that eventually became America’s oldest ultra, the JFK 50.

Kennedy’s Push for Physical Fitness

Fitness Test for Marines

Back in 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt issued an executive order that every Marine captain and lieutenant should be able to hike 50 miles in 20 hours. If necessary, this could be accomplished over a three-day period. For the final half mile, the test required the marines to “double-time” to the finish. In 1962 Kennedy discovered this executive order and asked his Marine Commandant, David M. Shoup (1904-1983), to falsely claim that the discovery was his. Kennedy then wanted Shoup to find out how well his present-day officers could do with the 50-mile test. Shoup made it an order to his Marines. Twenty Marine officers would be selected, ten captains and ten lieutenants to take the test in mid-February 1963, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

News Article Starts the Frenzy

An Associated Press article was published nationwide on February 5, 1963, that shared the story of the Roosevelt test and Shoup’s order to test 20 of his Marines. It received intense national attention. President Kennedy never directly challenged America to take the 50-mile challenge, and no walks were sponsored by the Fitness Council, but the article inspired many across the country, who were eager to test themselves too. Naïve, untrained citizens, immediately decided to hit the road without much planning to undertake the challenge in the middle of the cold winter. In response, the government tried to make it clear that they were not encouraging and sponsoring 50-mile hikes conducted by the public.

The Public Starts Hiking 50 Miles

On the very evening after the article was published, Lt. Colonel James W. Tuma, age 48 (1914-1990) from Michigan, the lone Marine stationed at Fort Huachuca, near Tucson, Arizona, read the article and immediately decided within minutes to start a 50-mile hike through the Sonoran Desert. You would think Tuma, who held a Ph.D. in physical education, would have more sense, but away he went at 9:05 p.m. on February 5, 1963. He said, “I wanted to do this thing for two reasons. To lend credence to the hypothesis that a Marine’s value to the corps is better expressed in terms of physical fitness and mental alertness, rather than chronological age. And to show Shoup that his independent duty Marines are also in shape.” Tuma used a 5-m.p.h. run/walk approached he called the “Apache Shuffle” for the first half and later settled into pace of about 4 m.p.h. He hiked through the night, not sleeping. He said, “Everybody was nice along the way, wanting to give me a ride.” The next morning, he finished his 50 miles with a sprint into the RCA plant at about 10:30 a.m., for a time of 13.5 hours and was credited as the very first one to finish 50-miles at the start of the nationwide craze. He said, “I had a notion I could do it.”

In Little Rock, Arkansas, five Marines started off the next night, hiking it “for the honor of the corps.” Two dropped out along the way, one with leg cramps and one with a twisted ankle. They didn’t carry any gear and ate light rations along the way. Three finished in less than 20 hours, along with a reporter. One mentioned, “I’ve got to admit it, it almost killed me.” Another, finished in stocking feet, carrying his boots, said, “I won’t be walking for the next couple of days. My feet are mad at me for the ordeal I put them through.”

At Pensacola, Florida, on the next day, Stanton E. Jordan, age 37, (1927-1988) ran the final 20 yards into his barracks before daybreak, completing the hike in 17 hours. He had hiked around a five-mile course at the naval air station and reported for work three hours later.

Press Secretary Challenged

The AP article reported that Kennedy mentioned that Roosevelt also wanted this fitness requirement “for members of his own family, members of his staff and Cabinet, and even for unlucky foreign diplomats.” He joked that his portly press secretary, Pierre Salinger (1925-2004), would “look into the matter personally and give me a report on the fitness of the White House staff.” When asked, Salinger said, “Either I or some other fitting individual from the White House staff will see what we can do.” Eventually Salinger backed out of the idea of personally trying to cover 50 miles and was made fun of in the press. He later explained how he got out of it. “I paced back and forth in my office (not too fast) and suddenly I got a brilliant idea. I called the president’s advisory committee on physical fitness and suggested it would be unwise for people who are not in shape to make the 50-mile walk. They agreed. I suggested that they give their views in a press release.”

The Physical Fitness Council issued a warning that “Anyone contemplating hiking 50 miles against time should be in good physical condition, should be in training, and should see a physician before starting out.” The American Medical Association advised gradual training. Podiatrists suggested using well broken-in leather shoes and two pairs of socks.

A former professional football player for the Green Bay Packers who was a doctor and director of student health for Michigan State University, called the 50-mile hikes, “foolhardy” and encouraged the public to leave the spectacular accomplishments for television. Few paid attention to these warnings. A national article reported, “From coast-to-coast Americans were on the march this weekend showing President Kennedy Americans indeed can march 50 miles or more.”

Robert F. Kennedy’s 50-mile Hike

On Feburary 9, four days after the story went public, Attorney General Robert F Kennedy decided to take the challenge himself and hike 50 miles. Without any specific training Kennedy hiked away on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal towpath with his dog Brumis. Conditions were cold with snow and slush during his quest with aides in tow. After 25 miles, the group was ready to give up. But the press had caught wind of what Kennedy was doing, and a helicopter arrived soon after with photographers and journalists. So, Kennedy set off again, this time accompanied by just two of his aides. His last aide dropped out by 35 miles, but RFK pushed on to the end and reached 50 miles in 17:50, accomplished in a pair of leather Oxford dress shoes. He said, “I’m a little stiff, but that’s natural, never having walked 50 miles before.” He recovered fast and the next morning went ice skating with his children. 50 years later, in 2013, a Kennedy 50-Mile Walk was established on February 8, 2013, to commemorate RFK’s historic walk and it is still held today.

Boy Scouts conduct 50-Mile Hikes

Within a week, boy scout representatives from all regions of the country visited the White House and brought a 50-mile hike patch for RFK. Since 1956 the BSA had a 50-miler award for their multi-day 50-miler hike that also included a conservation project.

In Wisconsin, four young boy scouts set off to walk 50-miles. Their scout master dropped out at mile 32 because he didn’t want to slow the boys down. They successfully hiked from Dodgeville, Wisconsin to Dubuque, Iowa.

Five boy scouts, age 13-14 in Illinois hiked 50 miles in 13.5 hours. The scouts were given a big welcome when they finished footsore and weary. One said, “I’m not ready to do it again tomorrow, but give me a month and I’ll be ready to go again.”

Servicemen Eager to Prove They Could Do It

In Naha, Okinawa, Japan, Harold R. Dent, 23, of Burwell Nebraska decided to go for 100 miles on February 6, 1963, in wind, rain and sleet. Dent stopped at 50 miles for a medical check-up and fresh footwear and halted at 75 miles for a two-minute rub-down of cramping muscles. He generally ran alone, but a few soldiers jumped in now and then and his battalion commander joined him for the last ten miles. He finished his 100-mile run in an amazing 16:42:48. This was the first-known sub-20-hour 100-miler for an American in the modern, post-war era, and would be the unofficial 100-mile American record for 8 years. Afterwards Dent only had a few sore muscles, no blisters, and just two pair of badly worn-out shoes.

Everyday People Hike

A 26-year-old mother of three, from Lincoln Nebraska, Pauline Domico, set off on her own 50-mile hike from Lincoln to the Missouri River at 3:45 p.m., just three days after the AP article was published. She called it her “March to Missouri,” and carried a 20-pound duffle bag with a change of clothes, shoes, flashlight, candy bars and sandwiches. Of her night hike, she said, “Fog swirled about me most of the night. Temperatures lingered in the low 30s. After 15 offers of rides, I quit counting.” She rested for only 20 minutes during the night. But stopping to rest made it hard to get moving again, so she decided to just keep going. During the last mile, she was greeted by a Marine recruiting officer who walked with her to the finish. She completed her hike in 20 hours and was the first-known woman to complete the 50-mile hike challenge. She said that the country is in sad shape it its people can’t hike 50 miles. She wanted President Kennedy to know that she wasn’t an athlete, but rather inclined to piano-playing, reading, sewing, baking, and writing poetry. Her first request upon finishing was for a comb.

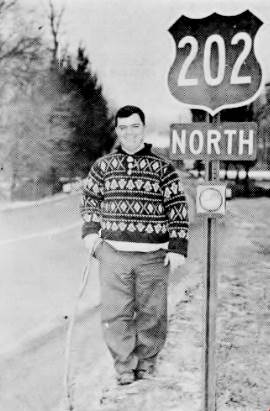

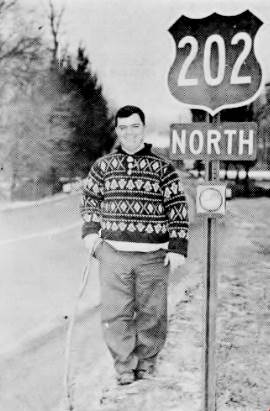

Francis Wulff, 24, a policeman and ex-Marine from Somerville, New Jersey hit the road to prove his physical condition. He said that he used to be able to walk 50 miles in 10 hours when he was a Marine. “I judge this will take about 15 hours although I am shooting for 12.” He chose a route randomly on a map and measured it with his car. He finished in 14.5 hours.

As the craze got going, the Amos Alonzo Stagg Foundation offered 50-mile medals to anyone finishing the challenge in 20 hours or less if they sent 50 cents to cover mailing and handling.

Safety became a serious concern. Many hikers would walk on freeways and not face traffic. In Oregon a teenager narrowly missed being struck by a car as he wandered onto the highway.

Newspaper reporters thought it was amusing to report that there were laws on the books in North Carolina and other places that endurance events could not be more than eight hours. These were put into place in the 1930s to combat the walkathons of that time. In North Carolina, the penalty was 30-90 days in jail and fines up to $500 dollars.

A Newspaper reporter from Baltimore hiked. His reaction was: “The walk was for the birds, only they’re smart enough to fly. Nobody, but nobody should attempt it unless it’s a matter of survival.”

Records

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) Handbook at that time stated the record for 50 miles was 9:29:22 set in 1887 which is a very slow time and very unlikely record, given fast performances over the recent decades. But the AAU said, “In the interest of President Kennedy’s physical fitness program, we will consider faster times made on unsurveyed courses for listing under ‘noteworthy track performances.'” That quickly spurred people to seek after records.

In Florida, Gene Flaherty, an Engineer, thought the world record for 50-miles was 9:27 set in 1878. Flaherty also managed an Amateur baseball team. He sought to break the “record,” receiving pledge of $125 to the team if he broke the “record.” He attempted to run from Cocoa to Orlando, Florida, but collapsed after only 19 miles and attributed his failure to “improper training”

A Marine lieutenant at El Toro base in California claimed he set a 50-mile record, completing it in 10:30. In Carson City, four high school teachers claimed a world record walking 50 miles in 12:58. A Eugene, Oregon, high school junior, Garry Kryazak, claimed a world record of 7:12. He said, “I’ll never do this again, at least not this year.”

In Houston, a former University of Houston distance runner, John Macy, 32, using pacers, achieved a 50-mile run of 5:29 and at that time it was thought to be a world record by the National Track and Field Federation, but they admitted such a record has not been kept before. Macy ran from Galveston to Houston. His achievement put to rest the many false claims of 50-mile records.

The Great Marin County Hike

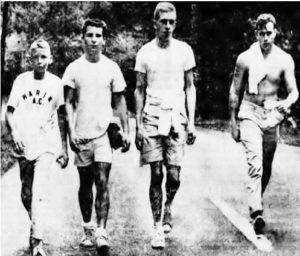

Four members of two track teams finished first in 12:08. One said, “We are pretty pooped.” Forty finished within 16 hours and others straggled in later. In all, 97 completed the 50-miles in less than 20 hours, 78 boys and 19 girls.

The first girl to complete the walk was Diane Congdon, 16. who finished in 13:29 with a 8-pound pack. She was a member of the Laurel Track Club of San Francisco and hoped to one day be on the U.S. Olympic team. When the bulk of the kids finished, “they were met by darkness and gathering of proud, bemused parents.” By midnight, the grueling journey was over. All the kids who participated “came through in fine shape – efor the blisters and tired muscles. The hikers were an interesting and merry lot.” Among those who didn’t make it all the way was eight-year-old Judy Aylwin who was very disappointed that she needed to drop out after 42 miles.

About a week later, an estimated 3,500 Portland, Oregon youths set off to hike to Salem, Oregon. Some made it. Parents followed the walkers by car and police patrolled at night. Some walkers who made it to Salem were stranded at the Capitol thinking there was food and buses waiting for them. The first one to finish in 8:24, was a 16-year-old cross-country runner, Larry Thompson, who said “My chest feels okay, but my legs are about ready to drop off. He drank five bottles of pop and ate hamburgers and french fries along the way.

Capital Hill Secretaries

The Official 50-Mile Marine Test

The men started in staggered groups. Each man was on his own and needed to circle a 25-mile course twice at any speed he desired. There were three rest stops that could be used along the way. They needed to finish within three days and their hiking time must not exceed 20 hours. Early in the march, General Tompkins smiled, but as the hours passed his face stiffened into a frown and he battled pain from his leg that was badly wounded in combat at Saipan.

Second Lieutenant Marty Shimek, of Hazen, Arkansas, was in the 6th group. He had run long distance at the University of Arkansas and by the 12.1-mile checkpoint he was in first place with a time of 1:45. He had developed a blister on his heel but pushed on running and walking. Shimek would go on to finish with the shortest moving time of 9:53, but he took just over 24 hours to do it.

“Although there were numerous red faces and a few piteous cries for water as the marines pulled into the rest stops” by noon not one had dropped out during the rainy morning.

In second place was Lt. Harry J. Crossen Jr. of Philadelphia who finished in 11:50. During the early miles his socks became very soggy because of the rain and mud. After 18 miles, he had such a bad case of blistered feet that it looked like he might have to drop out. But medics bandaged up his feet and he moved on. He said, “They really patched me up.” Once he finished, he was asked what his plans were, “I just want to get to the damned bathtub.” (In 2018, Crossen was 80 years old, living in Montville, NJ).

General Tompkins finished, 9th in 18:02 ahead of 25 other officers. By mid-morning of the next day, 14 or the 34 had finished.

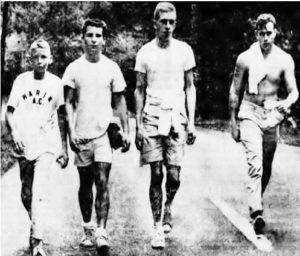

The Birth of the JFK 50

The CVAC 50 in 1963 was a private club event that responded to the Kennedy challenge. it was planned for about 53-miles. One runner recalled, “There was absolutely no race component to it. It was just, ‘Can we do it?’” The CVAC hikers would travel very light, carrying only a supply of band aids and a sandwich or two. Pumps along the C&O Canal towpath would be used for water along the way. The plan was to not stop long at any stops. Buzz didn’t advocate any special kind of shoe, just “a comfortable walking shoe.” Rick Miller, a sophomore in high school, dressed in khaki pants, a button-down shirt, and carried a bag lunch. All but three of the entrants were high school students. Sawyer was the only one who had any previous long-distance hiking experience, a 25-mile jaunt from Raleigh to Durham, North Carolina.

The route started at Boonsboro High School, southeast of Hagerstown, Maryland, and went along Route 40 to the Appalachian trail. From there it went to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia and then along the C&O Canal trail to Downsville and then finishing at St. James School in Hagerstown.

Eleven starters left at 6 a.m. Three fell behind immediately and decided to take a side route. Sometimes the participants would break into a run for a mile or two, getting ahead of Sawyer and then lying on the towpath waiting for him to catch up. Only four finished, all in 13:10. Sawyer was one of them. When they arrived, it was dark, so Sawyer called off the mile run around the track. The total miles were about 51 miles. Along the way they spent 1:16 resting and eating. Four other starters made it to mile 42.1 before dropping due to fatigue. The other three who took a short cut made it to the finish, going about 42.9 miles, but only 27.3 miles on the established course. The finishers that first year were James Ebberts (age 16), Steve Costion (age 16), Rick Miller (age 16), and Buzz Sawyer. Sawyer said there was no plan for any more hikes in the near future.

JFK 50 – The Early Years

There was one lone exception. In Maryland, the young high school runners who were members of the CVAC went to Buzz Sawyer and asked if they were going to do the 50-miler again and they did. Sawyer said, “The kids kept it going.” Because this event had an organized structure backed by the CVAC, the 50-miler lived on while all other events disappeared.

In 1964, the second annual CVAC 50 Mile Hike was again held and was also called the John F. Kennedy 50-Mile Hike. It was still a private club event. The route was the same as in 1963, as it would be for all the early years. Two of the previous year’s finishers were back, Ebberts and Costion. They boldly predicted that they would finish in twelve hours. Sixteen runners started and the temperature was in the low 20s. Ebberts and Costion again tied for the win along with Wayne Vaugn. They came close to their prediction, finishing in 12:33, running much more that year. Medals were later presented to the seven hikers who finished in less than 16 hours.

In 1966, six girls ran. Three dropped out at 20 miles and the other three made it to 25.

In 1967, the CVAC encouraged more non-club members to enter, but it still was dominated by members. An anonymous donor put up $50 for the first female finisher. Two women entered that year but didn’t finish. Ebberts, Vaughn and Sawyer tied with a new record, 10:03. There were 19 starters and 12 finishers. The women only went 9.7 miles.

1968 saw the first female finisher, Donna Aycoth, who tied for 2nd place overall with 10:41. She had been training with the all-male CVCA. She would go on to be the women’s champion every year through 1973. She didn’t hang around at the finish very long because she had a date that evening and her “hair was a mess.” Donna trained on the local YMCA balcony track during the winter and had clocked at 5:05 miles. She ran the length of the race with Sawyer. With eight miles to go they caught up with Wayne Vaughn and finished together. (In 2018 Donna was age 68, still living in Hagerstown, Maryland).

In 1969 the race became a big-time race with 153 entrants and 40 finishers. The winner finished in 8:32. In 1970 there were 275 starters and in 1971 there were 589 starters with 150 finishers.

By 1972 there were about 1,100 starters and the race attracted the most elite ultrarunners in the country. Legendary ultrarunner, Park Barner won in 6:29. In 1973 the starting field was 1,724, the largest ultramarathon ever held in U.S. history. The JFK 50 was well established and would live on for decades.

During 1963 there were hundreds of 50-mile events, participated by tens of thousands of people inspired by President Kennedy’s challenge to the Marines. The frenzy only lasted a few months, but one race remains as a reminder of that impactful several months when America hiked.

Sources

- Associated Press articles, Feb 6-7, 1963

- Life Magazine article, Feb 22, 1963

- The Minneapolis Star, Feb 11, 1963

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Feb 12, 1963

- The Greenwood Commonwealth (Mississippi), Feb 13, 1963

- Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb 14, 1963

- Oakland Tribune, Feb 12, 1963

- Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), Feb 14, 1963

- Del Rio News (Texas), Feb 13, 1963

- Brett and Kate McKay, “Take the TR/JFK 50-Mile Challenge,” May 24, 2017

- Orlando Sentinel, Feb 24, 1963

- The Post Crescent (Wisconsin) Feb 18, 1963

- Dayton Daily News, Feb 12, 1963

- Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), Feb 12, 1963

- The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), Mar 29, Apr 1, 1963, Apr 6, 1964, Nov 10, 2012

- Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 17, 1964

- The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey) Feb 15, 1963

- Dayton Daily News, Feb 10, 1963

- Lincoln Journal Star, Feb 10, 1963

- Arizona Daily Story, Feb 7, 1963

- El Paso Herald-Post, Feb 8, 1963

- Hope Star (Hope, Arkansas), Feb 9, 1963

- The Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1928