Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:16 — 32.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

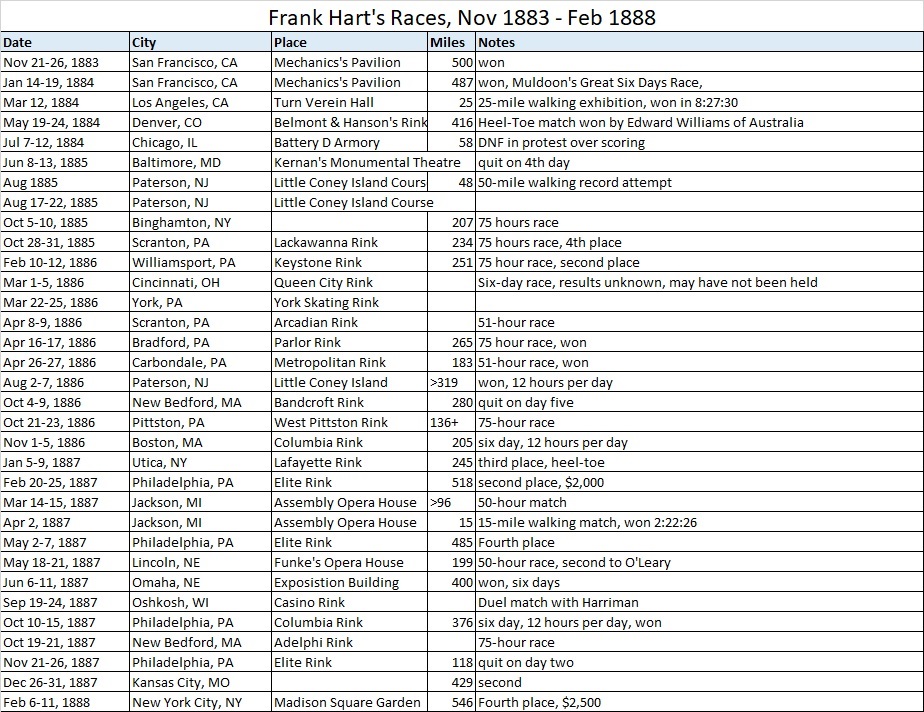

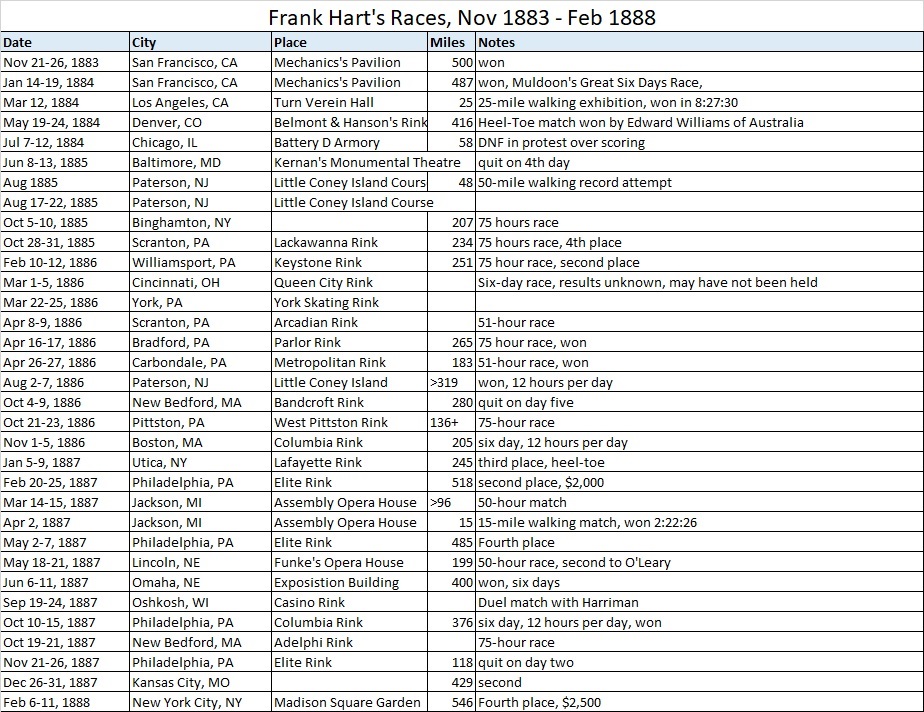

Frank Hart’s life in 1883 was at a low point. He had squandered his riches and damaged his reputation as a professional pedestrian. He was viewed as being hot-headed, undisciplined, and a womanizer. His wife and children were no longer being mentioned as being a part of his life and by then were likely gone. Many people had tried to help him, even his original mentor, Daniel O’Leary, who called him “ungrateful.” Trainers did not last long working with him. Hart was no longer referred to by the flattering title of “Black Dan.” Certainly, some of the criticism against him was because of racial stereotypes, which he fought hard against. He wanted to regain the glory and fame he had felt in previous years.

To make things worse, he had a young woman, Frances “Fanny” C. Nixon, arrested, accusing her of stealing a diamond ring from him valued at $526. The press was quick to point out that a black man was accusing a white woman, unheard of at the time. She had met him at his 1880 world record race at Madison Square Garden and they developed a relationship. He claimed that the night before he left for England in 1881, she had stolen the ring from his vest pocket. She countered that he had given it to her as a gift before he left. She admitted that she later sold it to a pawnbroker for $250. The court released her on bail and apparently the case was soon dismissed or settled.

California Here Hart Comes

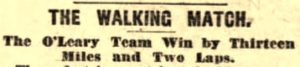

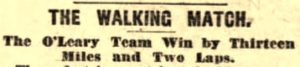

On November 8, 1883, Hart left Boston to travel to California for the first time. Money in pedestrian contests was becoming harder to find, and it was hoped that the West Coast would deliver. He was invited to compete in a six-day race in San Francisco with O’Leary, and two Californians, Charles A. Harriman, and Peter McIntyre, in what was called a “four-cornered” match. The East Coast team’s miles would go against the West Coast team. They put in a rule against any “hustle, push, impedance, or interruption with any other contestant” because of Hart’s known aggressive conduct in races.

Hart Gives a False Identity

But Hart, wanting even more attention, characterized himself as a wealthy lawyer. An article was printed stating that he was a member of the Boston Bar. “Owing to an unfortunate stutter, Hart is a poor pleader, but his opinions on legal matters are so sought for that he is able to hire a pleader to present his ideas in court.” The lawyer news surprised the Boston Globe, and it implied that the claim was fiction. He also stretched the truth of his recent six-day accomplishments, claiming that he held the current world record.

The New York Sportsman got wind of Hart’s “lawyer profession,” claim, and a correction was later printed in a San Francisco newspaper. The New York editor wrote, “Hart may be a great lawyer–we have never heard him plead for other than a release from a creditor. Before reading the story of Hart’s great ability as a lawyer, we thought his fame rested chiefly on his reputation as a pedestrian and a masher (a man who chases after women).”

California Four-Cornered Six-day Race

The San Francisco Four-Cornered race began right after midnight on Nov 21, 1883, in Mechanics’ Pavilion. At the end of day four, the match was tight. Hart had a one-mile lead with 370 miles and his team score with O’Leary led by only five miles.

A gossip paper wrote, “Hart has nearly all the time from two to a half-dozen white female visitors in his tent, and on the track, he is the frequent recipient of loral offering from the fair sex. One lady tossed him a bunch of violets as he was walking by, which he did not see. She, thinking herself slighted, brought about an explanation and the little affair terminated happily, the parties becoming fast friends.”

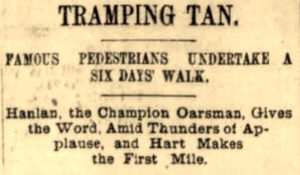

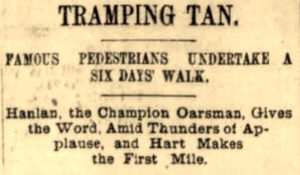

Muldoon’s Great Six Day Race

![]()

![]()

California Fame Exhibitions

Hart left California and headed back east to get ready for the next big race in Madison Square Garden at the end of April 1884. After two weeks, it puzzled people because he hadn’t arrived yet and assumed that he was training on the way back. Hart’s New York friends had sent Hart $175 to pay for his expenses to travel back from California and they too didn’t know what was going on. They assigned him a hut for the race, but he was a no-show as the start approached. In this race, Patrick Fitzgerald broke the world record with 610 miles.

Colored Baseball?

Where was Hart? It turned out that he stopped in Denver, Colorado, to put together a lucrative match to be held there later in the month. He sent word to the New York race management that he was in Chicago and had joined a semi-pro “colored” baseball team. He claimed he was hired to play shortstop on the Black Stockings in St. Louis, Missouri. The claim that he played for this team is very much in doubt.

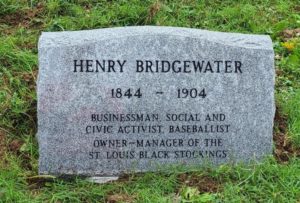

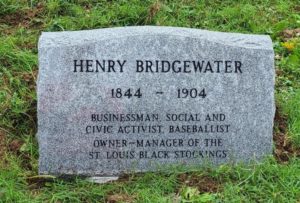

The Black Stockings were owned and managed by Harry Bridgewater (1844-1904) who had been born into slavery and became one of the most influential and wealthiest black businessmen in St. Louis. He had a goal of organizing a national black baseball league, but it never came together during his lifetime. Bridgewater evidently had recruited Hart to play for him. Hart played briefly in 1883 for the Boston Vendome Hotel Black Baseball Club, and for Saratoga Springs’ Leonidas Black Baseball Club, so he had some baseball experience.

While Bridgewater was putting together the baseball team and season, Hart was still competing as a professional ultrarunner. A six-day heel-toe walking match was held in Denver, Colorado, at Belmont & Hanson’s Rink, for him to compete against William Edwards, an experienced pedestrian from Australia. Edwards won 426 miles to Hart’s 416 miles.

Other histories about Frank Hart are in error when they claim he played in a high-profile baseball league. They only reference his likely fake published excuse for not showing up for the race in Madison Square Garden in April 1884. He couldn’t be in two places at the same time. He continued to compete in running races.

Six-day Brawl in Chicago

On July 7, 1884, Hart competed in a six-day match in Chicago put on by O’Leary, at the Battery D. Armory. It turned out to be a terrible fiasco. Hart quit the race after 58 miles, claiming that he was not being scored fairly. His nemesis, Hughes, later went on a tirade, causing a “free-for-all-fight” on the track. The police had to break it up. The police sent Pedestrian Daniel Burns (1860-1914), of Elmira, New York, to jail and gave Hart 24 hours to leave the city.

![]()

![]()

Despite being in the lead, Hughes quit the race, claiming it was fixed and that the scores were not being accurately recorded. He claimed that George Noremac assaulted him, and his wife and child were assaulted as he was being driven from the track.

O’Leary denounced Hughes’ statement as a lie. “He said Hughes was a chronic kicker and had been barred from walking matches all over the country. He started the fight and two of his friends tried to help him, and they were arrested.” The race went on because O’Leary paid bonuses to those who stuck it out. “Financially, the match was a fizzle” because it competed with the Democratic National Convention in town.

In August 1884, Hart put on a 25-mile exhibition in Springfield, Ohio, but was “deeply disgusted” because only a dozen spectators came out. He quit after only going 12 miles. “Many thought him a counterfeit of the genuine Hart, but he walked enough to show that he was a professional.”

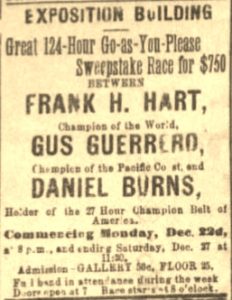

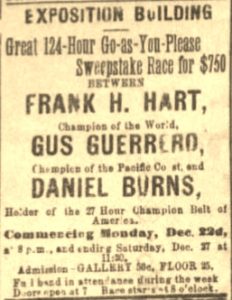

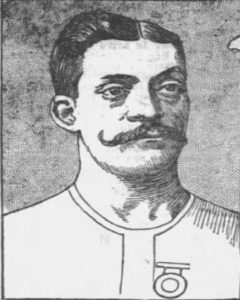

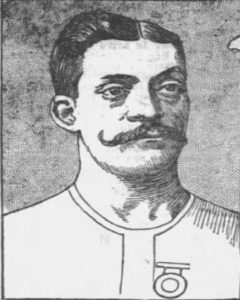

The Bizarre Memphis Fraud Race

During the fall of 1884, Hart traveled in the Midwest, trying to drum up running matches with little success. He next went south to Memphis, Tennessee, for a 124-hour match held in the Exposition Building on December 22, 1884. A man named George Tidy, of England, arranged the event. Hart, Daniel Burns, and Gus Guerrero of California started. It turned out that Tidy was a fraud and skipped out as the runners were on their second day. He left debts behind of nearly $400. “Hart, Guerrero, and Burns are all still in the city and are not to blame for Tidy’s ugly work. They are very anxious to see him themselves.”

First Six-Day Roller Skating Race

Hart’s Lifestyle

In 1885, it was reported that Hart had squandered $50,000 that he had earned over the past five years. That was worth $1.5 million today. He seemed to never have a home and likely lived in posh hotels as he traveled around the country. In November, Hart returned to Boston after being away for 2.5 years. Clearly, he had abandoned his family, who were still living there. His loyalty to Boston had wavered. In one race, he listed his residence as Bradford, Pennsylvania.

Barnstorming Pennsylvania in 1886

After participating in several 1885 races in the New York area and winning little money, it was announced that for the next year, he had allied with Charles A. Harriman, called the “Harriman and Hart Pedestrian team.” They were an interesting pair. Hart was “short and thick,” and Harriman was “tall and slender.” They planned to barnstorm Pennsylvania in 1886, go to California, and then on a 3–4-year trip to Australia

Things got off to a rough start. In January 1886, at Elmira, New York, they were barred from a race because fellow veteran pedestrians refused to let them start. The objection seemed to be because of their alliance, and the potential for shady tactics.

For the next few months in 1886, they competed in several 75-hour races in cities across Pennsylvania. With this three-day format, they could do a race every other week, rather than once-a-month six-day races. It was all about trying to make a lucrative living. Even so, running over 200 miles in each of those races took a toll. So, they next put on weekly 51-hour races, covering over 150 miles. Hart certainly was piling up the 100+ mile finishes, with about 35 thus far in his career

But these Pennsylvania races had problems because of dishonest managers who didn’t pay bills, and at times they were boring events for spectators, watching worn-out runners. After one race it was written, “All parties were disgusted with the contest.” Hart’s reputation was no longer great. He was referred to as “Ex-Champion.” The alliance with Harriman only lasted about four months, and by June 1886, the Pennsylvania barnstorming tour ended.

Failure in New Bedford

Hart Organizes His First Race

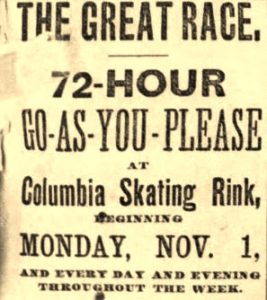

Since it seemed like Hart couldn’t win money in races anymore, he went into the race-organizing business. His first was a six-day, 12-hours per day, 72-hour race, put on at the Columbia Skating Rink in Boston on November 1, 1886. The race went well, but Hart quit after 205 miles because of bowel issues. Gus Guerrero won with 404 miles.

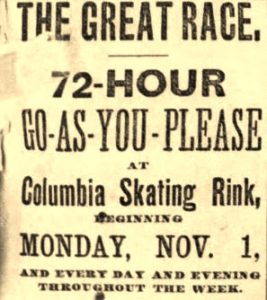

Hart Arrested, Freed, and Flees Boston

Hart’s greed and lack of business sense got him into big trouble. After the race, he was charged with confiscating funds from Edward E. Grant (1845-1888), who served as the manager of the race. Officers stunned Hart when they arrested him the day after the race in front of his hotel. He said, “All the money I received from Grant yesterday was $637.38, out of which I paid the band $90 and Bose Cobb (rink owner) $133.12, leaving $414.20 for me to account for.” He stated Grant and others wanted to exclude him from the profits. He said, “This is my reason for keeping the money, as I am not going to be played for a fool any longer.”

The biggest problem was that Hart was supposed to share the profits with the top finishers of the event, and he did not. The police held him for an hour, but determined the matter was for a civil court, not a criminal court. After they released him, he said that he was determined to keep the money. He quickly left Boston and was criticized in the press for “leaving the walkers in a rather poor financial condition.” His reputation in the sport took yet another big hit.

Hart’s despicable greed and behavior appalled the Boston public. He had finally burned bridges with his hometown. They organized a “grand benefit” for the race winner, Gus Guerrero, to raise deserved money for him that Hart had run off with. People attended the evening event full of running exhibitions and it was a great success. A month later, it was reported, “Frank Hart, who is called the lazy colored pedestrian, says he will enter legal proceedings against a Boston paper for publishing his portrait and placarding him as a thief.” He threatened to sue for $20,000 and claimed Fall River, Massachusetts, as his home. He resented being called lazy, especially by men who had never tried to run hundreds of miles.

Philadelphia Diamond Belt Six-Day Race

In late February 1887, Hart, now age 30, completed at a huge six-day race in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with most of the greatest ultrarunners of that time, even Gus Guerrero, whom Hart had recently swindled. John Hughes, Hart’s racist nemesis, was also there. “Hughes harangued the crowd and said all he wanted was fair play. He kept up his ill temper until near the starting time. Then he went outside the building and did not return.”

Hart still had speed and completed the first mile in first, in 6:10, but Guerrero soon overtook him. In this highly competitive race, after day one, Hart was in fourth place with 103 miles, and after day two in second with 201 miles. He finally had a good race again and held onto second place after day three, with 289 miles and 367 miles after day four. On day five, it was reported, “Hart is still the freshest man on the tanbark and his walk is without the slightest trace of a limp.”

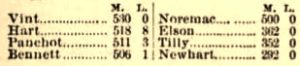

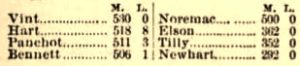

In the end, Hart finished in second place with 518 miles, twelve miles behind Robert Vint (1846-1917), an Irish-American and shoemaker from Brooklyn, New York. Hart won a much needed $2,000, but he was a sore loser. “Hart is a little disgusted at not winning first money and claims it was the fault of his trainer, who would not allow him to cover enough ground the first two days.”

The building was jammed when the final results were announced, and the police worked to shove the crowd into the rear center of the floor. “They were still pushing men out of the way when one of the large rafters holding the floor up from the cellar broke with a noise something like that of a muffled cannon and the floor began to sink. The officers were the first to run and a regular panic ensued, the crowd shoving and knocking each other down in their attempts to get away from the spot. Quiet was finally restored and the floor fell no further. No one was severely injured.”

Hart Organizes Another Race

Hart competed successfully in Nebraska, and after a win, was given a huge reception. His reputation was improving until he organized a six-day match against Harriman in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in September 1887. Hart was up to his old tricks again. “W. A. Gregg, who officiated as Hart’s trainer, claims Hart skipped out Sunday without paying his bills, among them being one due Gregg for his services. Gregg said that last spring after a six-day race in Boston, he skipped out with all the gate receipts, and all people ought to be warned against Hart.”

In November, at a highly competitive six-day race in Philadelphia, Hart tried to keep up with the new ultrarunning sensation, George Littlewood (1859-1912) of England. On day one, Hart burned himself out and had to drop out after 118 miles. Littlewood won with an amazing 569 miles.

Hart closed out 1887 by disappointing Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in not showing up for their race. He sent a letter letting them know he was ill, but that was a lie. Instead, he competed that same week in a more lucrative race in Kansas City, Missouri where he placed second with 429 miles..

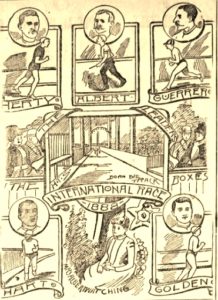

1888 International Go-As-You-Please

In February 1888, Hart competed in another historic international six-day race held at Madison Square Garden with 47 starters put on by Frank W. Hall. The field included five athletes of color, Hart, Edward Williams, Merritt Stout, “the Arabian,” a painter from New York City, William Burrell, of Chicago, and Fields. Hart was no longer a feared champion, but still respected as one to watch out for. At the start, the old building, planned for demolishment, was packed “as full as a sausage case,” with about 12,000 people. Hart was dressed in a blue shirt, red trunks, gray tights, and an old, checkered jockey cap.

They had constructed a spectator bridge over the track for those who wanted access to the infield that contained a lemonade booth and a newspaper stand. Other attractions were knife-throwing boards, baseball targets, cane racks, and places to buy railroad sandwiches, sawdust pie, soda water, popcorn, candy, fruit, and a bar with 100 bartenders dealing out beer. Cries of “’Drop a nickel in the slot’ caught the people curious of their own weight, their lifting powers and the strength of their lungs, and those who were partial to tutti-frutti chewing gum”

There were 150 scorers hired for shifts. Callers shouted out the number of the runner as they passed under a wire, identified by a black card on their chest. There were mistakes with so many runners. Hughes, as usual, complained that he had been short-changed two miles. Others, including Hart, stopped at the scorers’ stand to protest strongly. The scorers, under Edward Plummer’s leadership, threatened to quit unless they were left alone and allowed to take breakfast breaks.

A fight occurred on the first day and for once, Hughes and Hart were not involved. Robert Vint didn’t like John Dempsey, a boxer, dogging his heels and hitting them. “Vint got a blow in the mouth from Dempsey’s fist bringing blood. Dempsey called Vint a name which he didn’t take kindly to.” Vint dislocated his thumb from a punch.

Another disruption occurred on the track. “Policeman Creighton essayed to suppress a one-legged boy of fourteen years, but the cripple refused to leave the path of the men and when the policeman attempted to take him out of the Garden, the boy fought him using his crutch for a weapon. The rebellious lad was locked up.”

James Albert (Cathcart) (1856-1912), from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, broke the six-day world record with 621 miles. Hart had now witnessed the breaking of the world record five times. In this race, eight men went over 525 miles.

Hart won about $2,500. “Frank Hart was a badly used up winner. He was hoarse and trembling. He denies that he was lazy and says that no lazy man would ever go into the six-day business. He is to leave it and expects to be appointed a Philadelphia policeman or go into the business there. Hart once made a fortune as a champion walker but enjoyed life too well to keep it.”

He and others believed strongly that the race manager, Hall, had cheated them, taking too much profit, something Hart had previously done himself and thus he had no room to complain. He said, “There isn’t the ghost of a doubt that crooked work was done.” He was so upset that he swore he would never enter another race.

Sources:

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 31, 1882, Sep 10-11, Nov 8, 20, 1883, Jul 16, 1884, Mar 1-10, 15, 17, Apr 10, 13, 16, May 8, Aug 10, Nov 28, 1885, Oct 9, 14, Nov 9, 28, 1886, Feb 12, 1888

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Nov 8, 11, 15, 18, 22-25, Dec 4, 1883, Jan 3, 7, 11-20, Feb 21, 23, Mar 24, Jul 7, 1884

- The Record Union (Sacramento, California), Nov 17, 1883, Feb 11, 1884

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Jan 20, 1884

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Mar 24, 1884

- The Sun (New York, New York), Apr 23, 1884, Feb 12, 1888

- The New York Times (New York), Apr 28, 1884

- The Evening Telegraph (Buffalo, New York), May 3, 1884

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri) Jun 4, 1884

- Frank Hart (athlete)

- Brooklyn Times Union (New York), May 22, 1884

- The Butte Miner (Montana), May 25, 1884

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Jul 8, 1884, Apr 3, 1887

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jul 13, 1884

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Aug 15, 1884

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Sep 27, 1884

- Memphis Daily Appeal (Tennessee), Dec 7, 26, 1884

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Aug 11, 1885

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Aug 14, 1885

- Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) Oct 16, 1885

- The Democratic Age (York, Pennsylvania), Mar 23, 1886

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Apr 18, 1886, May 23, 1887

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Jan 16, 1887

- Halifax Herald (Nova Scotia, Canada), Jan 22, 1887

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Feb 21-27, May 2-7, 1887

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Feb 21-27, May 2-7, 1887

- Sunday News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), May 8, 1887

- The Oshkosh Northwestern (Wisconsin), Sep 27, 1887

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Feb 6-11, 1888

- The Morning Call (Paterson, New Jersey), Feb 12, 1888