Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:22 — 32.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

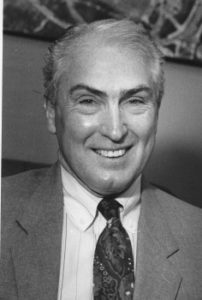

Dan Brannen (1953-) of Morristown, New Jersey, has made a lifetime contribution to ultrarunning and the running sport in general. His dedicated work, mostly from behind the scenes, helped to establish world and national ultrarunning championships. His efforts have affected thousands of ultrarunners in America and around the globe for decades. Dan was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame in 2022.

Dan Brannen (1953-) of Morristown, New Jersey, has made a lifetime contribution to ultrarunning and the running sport in general. His dedicated work, mostly from behind the scenes, helped to establish world and national ultrarunning championships. His efforts have affected thousands of ultrarunners in America and around the globe for decades. Dan was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame in 2022.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Frank Hart: The First Black Ultrarunning Star. In 1879, Hart broke the ultrarunning color barrier and then broke the world six-day record with 565 miles, fighting racism with his feet and his fists. |

Early Running

The Brannen family were Irish Catholics from Upper Darby, a suburb of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He went to Catholic schools growing up, including St. Joseph’s Prep in Philadelphia. In high school, he was required to participate in an athletic extracurricular activity. Dan explained, “I was a shrimpy little kid. I played little league baseball, but I wasn’t particularly athletic or coordinated. One of the sophomores who came in to give the orientation, said, ‘If you can’t do anything else, go out for cross-country.’ So, I did, my freshman year even though I was terrible at it.”

During Dan’s senior year, a new coach, Larry Simmons (1942-2004), a successful distance runner and racewalker took over the team. He lit a fire into the team and into Dan whose course times dramatically improved, resulting in his promotion to the varsity team. His rapid success, instilled by the inspiration of Simmons, turned him into a runner for life.

Dan went to Bucknell University in Central Pennsylvania and got in on the ground floor of a new cross-country team. His coach, Art Gulden (1942-2001) developed the team into a highly successful running program at Bucknell. Dan continued to improve under his tutelage and recalled, “Each year Gulden was able to recruit faster and faster high school runners. They included state champions, and it was very competitive. I was able to stay with the second tier of those guys. One of the best feelings I had about myself as an improving runner was when I was running and keeping up with state high school champions.”

Dan ran a few marathons during college, graduated in 1975, and joined the well-established road-racing scene in the Philadelphia and New Jersey area. He was a self-described “running bum,” living a subsistence lifestyle as he concentrated on his running passion. His weekly mileage would average about 100-120 miles per week.

His personal best marathon occurred at the 1979 Boston Marathon which he ran in 2:31:13. He was intoxicated with distance running and it would later evolve into a true career for life. Part-time he worked editing research manuscripts which enhanced his writing skills. He also coached cross country at his former high school for a few of these years in the late 1970s.

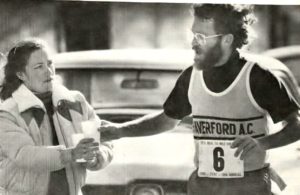

Dan was a member of the Haverford Athletic Club. Road running was very competitive in the Philadelphia area during the late 1970s. He became acquainted with the future ultrarunning legends in the area. “One of the prime organizers in the area was Browning Ross who was a great Villanova runner and Olympian. Browning founded the Road Runners Club of America and started the Long Distance Log which was the very first running magazine. I would go over to South Jersey and met Ed Dodd, Tom Osler, and Neil Weygandt in those races.”

Dan was a member of the Haverford Athletic Club. Road running was very competitive in the Philadelphia area during the late 1970s. He became acquainted with the future ultrarunning legends in the area. “One of the prime organizers in the area was Browning Ross who was a great Villanova runner and Olympian. Browning founded the Road Runners Club of America and started the Long Distance Log which was the very first running magazine. I would go over to South Jersey and met Ed Dodd, Tom Osler, and Neil Weygandt in those races.”

Dan ventured into the shorter ultrarunning races in 1978, running the Knickerbocker 60 km in Central Park, and ran in a few others the next year, including the classic ultra, Two Bridges 36-mile Road Race in Scotland.

Win at 1980 JFK 50

In 1980, Dan ran a 50-mile race for the first time at JFK 50 in Maryland. To convince himself that he could do well, he ran two sub-3-hour marathons on back-to-back days leading up to the race, a 2:58 at Kane, Pennsylvania, and 2:57 at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. He also did a 60-mile training run, from his home in Philadelphia to his aunt’s house at the Jersey shore.

In 1980, Dan ran a 50-mile race for the first time at JFK 50 in Maryland. To convince himself that he could do well, he ran two sub-3-hour marathons on back-to-back days leading up to the race, a 2:58 at Kane, Pennsylvania, and 2:57 at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. He also did a 60-mile training run, from his home in Philadelphia to his aunt’s house at the Jersey shore.

Dan went to JFK thinking that he might have a good chance to win. His specialty was gnarly, rocky, technical trails. He knew that he could stay with people who were faster than him on roads and hoped to keep up with the previous year’s champion, Bill Lawder (1947-) of New Jersey.

Dan’s JFK 50 start did not go smoothly. He explained, “I was probably the only person ever to win the JFK to start in absolute dead last and end up in first. When the gun went off, I was in the porta-potty with my sweats still on. I heard the gun, rapidly finished my business, and almost tripped over my sweats as I tried to get them off and run at the same time. When I got to the start line, I could barely see the final stragglers. I ran through most of the field for those first three road miles and mowed my way through the field until I caught and passed Bill Lawder with three miles to go on the Appalachian Trail.”

Dan continued, running an ideal race. Two others ahead of him soon dropped out and he went into the lead at about mile 20. He was later passed by Lawder on the C&O Towpath but caught him on the final long road uphill toward the finish and won by nine minutes with 6:14:02.

Racing and Directing Ultras

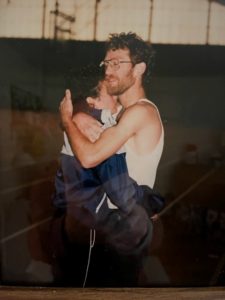

During the next few years, Dan branched out and started organizing and race-directed classic early ultras including the Great Philadelphia to Atlantic City race and the Haverford indoor 24-hour and 48-hour races. His first 100-miler was at Fort Meade, Maryland on a track in 1981, where he finished in third place with 17:45:56. In later years he would run trail 100-milers at Western States, Old Dominion, Massanutten, and Wasatch Front.

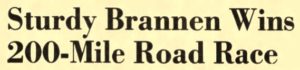

In 1982, Dan organized, ran, and won perhaps the earliest modern-day 200-mile race, the “Johnny Salo Road Race” across New Jersey from High Point, New Jersey, to Cape May. The race with 15 starters was named after Johnny Salo, perhaps the greatest American ultrarunner during the 1920s, who won the 1929 race across America, nicknamed “The Bunion Derby.” He was New Jersey’s hero. Dan managed to track down Salo’s daughter, Helen Salo Lotz, who brought family and some of her father’s memorabilia for a pre-race dinner.

Dan recalled, “I was very excited to have succeeded in recruiting two of the fledgling ultra era’s ‘living legends’ to run the event, American Park Barner and Max Telford of New Zealand. What none of us fully appreciated was that the course dropped over 1,000 feet of elevation in the first eight miles. Everybody’s legs were trashed after the first hour. After only about 3-4 hours both Barner and Telford dropped out. That left me in the lead, and I too felt like dropping out and continued to have that feeling hour after hour for the next two days. But the folks in Cape May had gotten quite excited about welcoming us to their small town. They had arranged reporters, photographers, and a significant number of the townsfolk to greet us at the finish. So, I felt obligated to continue.” Dan finished in 61:15:18.

Dan recalled, “I was very excited to have succeeded in recruiting two of the fledgling ultra era’s ‘living legends’ to run the event, American Park Barner and Max Telford of New Zealand. What none of us fully appreciated was that the course dropped over 1,000 feet of elevation in the first eight miles. Everybody’s legs were trashed after the first hour. After only about 3-4 hours both Barner and Telford dropped out. That left me in the lead, and I too felt like dropping out and continued to have that feeling hour after hour for the next two days. But the folks in Cape May had gotten quite excited about welcoming us to their small town. They had arranged reporters, photographers, and a significant number of the townsfolk to greet us at the finish. So, I felt obligated to continue.” Dan finished in 61:15:18.

At the Weston Six-day later held that year in New Jersey, he met Englishman Malcolm Campbell. Campbell expedited Dan’s entrance in the 1983 international La Rochelle 6 day in France. Dan finished 5th, running 468 miles to rank as #2 American for the year. Dan said, “It had an international feel to it. It was a spectacular environment. It was indoors, there were people in the stands surrounding the track 24 hours a day. They had a restaurant and band playing in the middle of the oval.”

In 1983, along with Neil Weygandt, they attempted to break the world two-man 24-hour relay record of 193 miles. They made their attempt on a track at Mullins Field in Fort Meade, Maryland, and successfully surpassed the mark with 199.5 miles, averaging 7:16-minute miles between them—only to later discover that two men in South Africa had run 201 miles the same weekend.

In 1985 Dan ran 223.2 miles indoors at Haverford 48 hours to break Ray Krolewicz’s 48-Hour American Record by a mile, only to lose it back to Krolewicz within a year.

Co-founding the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU)

Dan’s greatest contributions to the sport of ultrarunning came when he worked tirelessly to organize the sport worldwide during the late 1980s. Gary Cantrell (Lazarus Lake) wrote at that time, “Thanks, in large part to Dan’s efforts, our sport appears well on the way from being a mere diversion among running’s fringe element to establishing a place among respected amateur sports. Dan was aware of the effects when a governing body is unconcerned about and unresponsive to, the needs of a large group of constituents.”

In the early 1980s, Dan had mail contact with Andy Milroy of England who had been involved in the collection and ranking of international ultra statistics for several years, working with Antonin Heyda and Nick Marshall of Pennsylvania. Dan recalled, “It became immediately obvious to me the incredible value of Milroy. He was like a thorough-going archivist and statistician, and he was in touch with other like-minded folks. In our communications, everybody was getting some information about ultramarathons held in the United States, Great Britain, and South Africa. Those were the three countries we knew about, but it turned out that Milroy was getting information of events and movements in places like Japan, France, Bolivia, and even behind the Iron Curtain.”

The excitement and thrill of these communications inspired the idea in Dan that ultrarunning could be organized on a global scale. He proposed the notion of an international ultrarunning association through correspondence to Milroy, Edgar Patterman of Austria, and Malcolm Campbell of England.

Enthused and convinced that an organization was needed, Dan and the others went to work. In April 1984, at a three-day race in Austria, he co-founded the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU). The founding members were: Brannen, Patterman, Campbell, Milroy, Gerrad Stenger of France, and Harry Arndt (of West Germany.) Very soon thereafter the IAU Executive Council expanded to add Jose Antonio Soto Rojas of Spain, and Tony Rafferty of Australia (Rafferty, by his own choice, was soon replaced by Australian Geoff Hook).

Enthused and convinced that an organization was needed, Dan and the others went to work. In April 1984, at a three-day race in Austria, he co-founded the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU). The founding members were: Brannen, Patterman, Campbell, Milroy, Gerrad Stenger of France, and Harry Arndt (of West Germany.) Very soon thereafter the IAU Executive Council expanded to add Jose Antonio Soto Rojas of Spain, and Tony Rafferty of Australia (Rafferty, by his own choice, was soon replaced by Australian Geoff Hook).

Malcolm Campbell was chosen as the first IAU president, Andy Milroy as statistician, and Dan Brannen as general secretary. Dan would hold that position for about 15 years. Campbell had the charisma necessary to charm others and ease politics with other organizations.

In the June 1984 issue of Ultrarunning Magazine, Dan announced the formation of the IAU. “The preliminary goals of the association are: To foster communication and cooperation between ultrarunners of all countries, regardless of ethnic or national considerations, and to establish international guidelines for the conduct of events and for accurately measuring standard-distance courses.” In addition, they had goals to maintain ultrarunning records in some form.

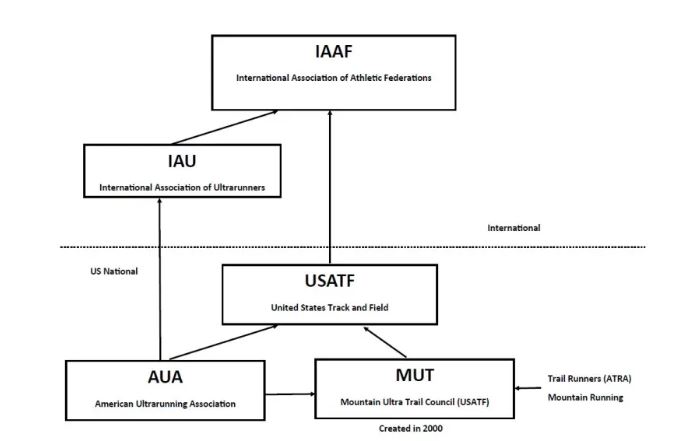

They knew that they needed to have cooperation with other sports bodies, in particular the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the international governing body over running competitions at the time. The IAAF was surprisingly receptive. They realized that the IAU was bringing in a new branch of the sport “on a silver platter.” With the support of the IAAF, they could make inroads to have ultrarunning recognized and supported in the various country federations.

They knew that they needed to have cooperation with other sports bodies, in particular the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the international governing body over running competitions at the time. The IAAF was surprisingly receptive. They realized that the IAU was bringing in a new branch of the sport “on a silver platter.” With the support of the IAAF, they could make inroads to have ultrarunning recognized and supported in the various country federations.

They started to work on an IAU charter, an international calendar of bona fide events, standardized lap-recording procedures, and guidelines for conducting ultramarathons on all surfaces, including trails.

Working to Legitimize the IAU

Skeptics of the new organization voiced their opinions. Fears were expressed that the IAU would be a governing body forcing runners to comply with stringent amateur eligibility requirements and qualification standards to complete in ultras. Dan quickly diffused these fears as being unfounded.

Throughout 1985, Dan and the other IAU executives worked to define their mission, making it clear that its activities would involve international communication and cooperation, and not in competition with any governing athletics or running organizations that governed the sport. Among their first goals was to develop an International 100 km and 24-hour world championship series.

World “Championships”

In June 1986 several U.S. men ultrarunners competed as an informal team in an international 100 km race that was not organized by the IAU. It was the Torhout 100 km in Belgium. There was some controversy about how the U.S. team members were selected for that race and received free airfare to compete. At that time there, of course, was no Internet, and poor grapevine communications were used to learn about international events and who were the right runners to be invited and some felt unfairly excluded.

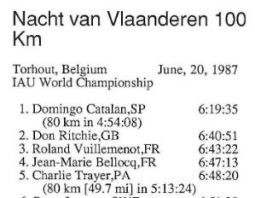

The Belgian Torhout race declared that their next year’s 1987 race would be “the world’s championship.” Any European race in those days could independently declare their race as a world championship. This and other perceived problems were issues that the IAU needed to solve for ultrarunners. In 1987 Dan was involved in negotiations with the Belgian Torhout 100 km in Flanders, arranging for them to host the first officially designated IAU World 100 km. Dan tried to help the ultrarunning community appreciate the delicate international politics around this. Issues were solved and the IAU sanctioned the 1987 championship.

The Belgian Torhout race declared that their next year’s 1987 race would be “the world’s championship.” Any European race in those days could independently declare their race as a world championship. This and other perceived problems were issues that the IAU needed to solve for ultrarunners. In 1987 Dan was involved in negotiations with the Belgian Torhout 100 km in Flanders, arranging for them to host the first officially designated IAU World 100 km. Dan tried to help the ultrarunning community appreciate the delicate international politics around this. Issues were solved and the IAU sanctioned the 1987 championship.

After the 1987 inaugural World Championship, the IAAF flexed its muscles and would not approve of letting the IAU call these events “championships.” Treading softly, beginning in 1988, the IAU then referred to these competitions as “World Challenges Under the Patronage of the IAAF.” It would take the IAAF more than another decade to fully embrace the IAU and allow any ultramarathon to carry the designation “World Championship.”

In 1988, the World 100km was held in northern Spain, the Santander 100 km. The IAAF was involved in a supervisory capacity and the race saw a wider number of elite runners from multiple continents and more than a dozen nations, along with the beginning of the participation of national teams. Ann Trason won with a world record of 7:30:49. Word was spread at European races about the IAU and the good work that was taking place.

The major long-lasting benefit of Dan’s work with the IAU was to establish the world championships, bringing together an international community of ultrarunners. A secondary benefit was that, due to the cooperative and mutually respectful relationship established between IAU and the IAAF from the outset, other national federations (in Europe, Oceania, Africa, South America, and Asia) which were disinterested in ultrarunning (sometimes dismissively and aggressively so) eventually allowed their ultrarunners and ultra events into their official framework, due to the powerful authority wielded by the IAAF over every national running federation in the world.

Gaining American Ultrarunning Acceptance

In America, The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), the official governing body of the sport, had been sanctioning a handful of ultras, ratifying a limited number of ultra records, and staging national championships since the 1960s. in 1978 the AAU was reformed by congressional federal law and re-named The Athletics Congress of the USA, usually abbreviated as “TAC.” In the early 1990s, it would change its name again to “USA Track & Field,” commonly now known as USATF.

In America, The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), the official governing body of the sport, had been sanctioning a handful of ultras, ratifying a limited number of ultra records, and staging national championships since the 1960s. in 1978 the AAU was reformed by congressional federal law and re-named The Athletics Congress of the USA, usually abbreviated as “TAC.” In the early 1990s, it would change its name again to “USA Track & Field,” commonly now known as USATF.

For American ultrarunning, official national championship record designation was limited to the 50K and 50-mile distances for men and women, and the 100-mile distance for men only.

In 1986, Ollan Cassell, a gold medal winner at the 1964 Olympics (4×400 meter relay), was the executive director of TAC. He had firm “iron hand” control over TAC at the time. Dan boldly approached him, expressing the wish to bring ultrarunning formally into the TAC federation. Cassell firmly denied the request, feeling that ultrarunning was too much of an outlier compared to the rest of the running sport. The president of TAC, Frank Greenberg, of Philadelphia, with whom Dan had been friendly from the Philadelphia road running community, encouraged him to not give up and go ahead and present the idea to the long-distance committee. They were very supportive, and he then presented to the entire TAC executive committee, where they voted in favor, despite Cassel’s objections. Once that decision was made by the executive committee it was just a matter of time until full TAC recognition was achieved for ultrarunning.

In December 1986, thanks to Dan’s work, a TAC Ultra Subcommittee was formed with Dan as the chairman. He served in that capacity for nine years.

The Ultra Subcommittee selected annual national ultra championships, advised TAC on ultra recordkeeping, made national team selections, acted as an information resource to the ultra community, and advised races that wanted to be approved for records. They expanded the contents of the rulebook to include the full range of national ultra records and championships. Dan worked with race directors to help them learn how to do more meticulous race timing record-keeping with split times and to get their courses properly certified.

The Ultra Subcommittee selected annual national ultra championships, advised TAC on ultra recordkeeping, made national team selections, acted as an information resource to the ultra community, and advised races that wanted to be approved for records. They expanded the contents of the rulebook to include the full range of national ultra records and championships. Dan worked with race directors to help them learn how to do more meticulous race timing record-keeping with split times and to get their courses properly certified.

Dan worked to help ultrarunning fit in and be accepted by the rest of the running world. Not all ultrarunners wanted their sport to identify with any formal organizations like TAC. This was especially true for many trail ultrarunners, who only wanted a free-wheeling, no-rules sport that had more to do with “adventure, risk, exploration, and discovery.” But Dan had the foresight to see the benefits of organization and communication, especially if records wanted to be recognized. He had to wade through the bureaucracy of TAC that included “turf wars, power-mongering, and politicking.”

Dan said, “Once it was obvious that this was going to work in a significant way within the federation structure, the ultrarunners came on board. I would go to the TAC annual meeting and significant players from the ultra community came, such as Rae Clark, Steve Warshawer, Roy Pirrung, and Kevin Setnes, among others. At the TAC awards banquet with 1,000 people from all over the country, we instituted the ultra-awards and presented them. The winners of the Ted Corbitt award, the outstanding ultrarunner of the year, got to walk up and be recognized in front of the entire track and field community of the United States.”

Dan said, “Once it was obvious that this was going to work in a significant way within the federation structure, the ultrarunners came on board. I would go to the TAC annual meeting and significant players from the ultra community came, such as Rae Clark, Steve Warshawer, Roy Pirrung, and Kevin Setnes, among others. At the TAC awards banquet with 1,000 people from all over the country, we instituted the ultra-awards and presented them. The winners of the Ted Corbitt award, the outstanding ultrarunner of the year, got to walk up and be recognized in front of the entire track and field community of the United States.”

Within a few years, Dan had virtually singlehandedly worked through the not always accepting or cooperative political labyrinth of TAC to achieve status for US national ultra teams and National Championships. Think of it this way, Dan attended all the boring meetings, and had all the fights with bureaucracy, to make it possible for ultrarunners to run, experience national teams, international races, and receive treasured awards.

Controversies

As with any effort trying to make high-impact changes in administration, the environment was highly political, and Dan was not shy about ruffling feathers and had many critics. Publicly, he stepped into the great debates conducted in Ultrarunning Magazine including if pacing should be allowed on trails if formal organizations helped or hurt ultrarunning if Badwater to Mt. Whitney FKT should be limited to the summer and the hotly debated South Africa boycott controversy.

In 1988, controversy arose as the IAAF had a global boycott in place of all running competitions in South Africa because of the continuing racial apartheid policies. They also banned any runners from South Africa from competing in their races in other countries until apartheid ended. Dan and the IAU tried to warn the ultrarunning community.

Further controversy arose in February 1989, when some world elite ultrarunners (from Europe and North America) participated in the international “Standard Bank 100 km” race organized in Stellenbosch, South Africa and the runners faced suspension by the IAAF and TAC. If suspended runners participated in another ultra, anywhere, race directors and potentially runners that participate in the ultra could also be suspended. Dan and the IAU had to wade into the issue with the IAAF and advocated leniency for temporary suspensions, but Dan made it clear that he personally had “no qualms about a ban against participation in athletic events that showcase a racist system of government.”

Dan received some heat from critics as he continued in his efforts to unify ultrarunning. Gary Cantrell defended his efforts in 1989. “Dan has strong opinions just like the rest of us. But as a leader, spokesman, and organizer, it is mandatory that representing the majority opinion and working for the long-term welfare of the sport take precedence over personal feelings. As a result, Dan has spent much of his time stuck in the middle between the stiff-necked administrators of amateur athletics and the bandits and renegades that populate the ultrarunning community. Fortunately for us, Dan has played the political game with the same intelligence and dogged determination that marked his running career. His perseverance has brought our sport to a level few would have predicted and through it all, Dan has retained his clear vision of what needs to be achieved.”

Ultra World Championships Began to be Held

In 1990, Dan’s efforts to have TAC officially recognize U.S. national ultra teams were approved. The inaugural IAU 24-Hour International Championship was held at Milton Keynes, England, complete with team uniforms. Dan was also instrumental in getting TAC, IAU, and IAAF approval for the 1990 100 km World Championship to be held at Edmund Fitzgerald 100 km in Minnesota. Dan and Bill Wenmark, the race director, worked tirelessly on the race.

The World Championship turned out to be amazing. “All the foreigners loved it. Andy Milroy said that the historic significance of that event was, that the first three places were taken by runners from three different continents and two different hemispheres.”

Apartheid ended, suspensions were lifted, the Berlin Wall came down, Germany was reunited (resulting in one of the most accomplished national ultra teams), and international ultra championships started to flourish worldwide, with much thanks to Dan. He had direct hands-on involvement in twenty-one U.S. National Ultra Championships, twelve 100 kms, and nine 24-hours. In addition, he was the manager/coordinator for U.S. Teams at nine World 100 km Championships.

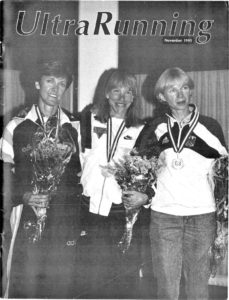

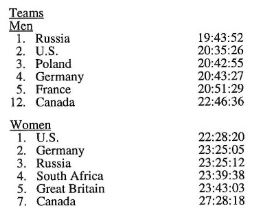

Dan’s greatest memory of a world championship was the 1995 IAU 100 km in Winschoten, The Netherlands. “That was the high point of America’s uncontested superstar of ultrarunning, Ann Trason who almost broke seven hours. The amazing thing is that the two American runners behind her ran what would have been world-winning performances too, Donna Perkins and Chrissy Duryea. It was an unbeatable team. They set the world team time record by some ridiculous amount. And the men’s team were not expected to finish on the podium, but they did, they finished second. Tom Johnson ran the race of his life and took the individual bronze and set the American record. I just remember the atmosphere. All the national team managers and runners came up and congratulated us. It was celebratory in the afternoon and through the evening. It was fantastic to be a part of.” The highly competitive international race was a great success for both the IAU and the American team.

Dan’s greatest memory of a world championship was the 1995 IAU 100 km in Winschoten, The Netherlands. “That was the high point of America’s uncontested superstar of ultrarunning, Ann Trason who almost broke seven hours. The amazing thing is that the two American runners behind her ran what would have been world-winning performances too, Donna Perkins and Chrissy Duryea. It was an unbeatable team. They set the world team time record by some ridiculous amount. And the men’s team were not expected to finish on the podium, but they did, they finished second. Tom Johnson ran the race of his life and took the individual bronze and set the American record. I just remember the atmosphere. All the national team managers and runners came up and congratulated us. It was celebratory in the afternoon and through the evening. It was fantastic to be a part of.” The highly competitive international race was a great success for both the IAU and the American team.

American Ultrarunning Association (AUA)

In 1990, Dan founded the American Ultrarunning Association (AUA), initially to serve as the USA representative organization to the IAU. It became a member organization of USA Track & Field (USATF) giving ultrarunning an official voice. Under Dan’s leadership, they succeeded in expanding the USATF list of ultra events for which records were kept and USA National Championships were held. The AUA also provided initial funding for US national ultra teams and administrative support for US national ultra championships. Dan said, “My focus with AUA was to have AUA serve as an information agency to the general public, to the press for historical perspectives.”

In 1990, Dan founded the American Ultrarunning Association (AUA), initially to serve as the USA representative organization to the IAU. It became a member organization of USA Track & Field (USATF) giving ultrarunning an official voice. Under Dan’s leadership, they succeeded in expanding the USATF list of ultra events for which records were kept and USA National Championships were held. The AUA also provided initial funding for US national ultra teams and administrative support for US national ultra championships. Dan said, “My focus with AUA was to have AUA serve as an information agency to the general public, to the press for historical perspectives.”

For his dedicated work, Dan was awarded USATF’s Presidents Award in 1992, the highest honor given to volunteers for administrative accomplishments at the national level.

Dan has been a prolific writer for the sport. Over the years he published at least 40 articles in Ultrarunning Magazine including an excellent history of American ultrarunning, co-authored with Andy Milroy, in at least 16 parts in 1998-99.

In 1991, Dan won the Lew Gibb Award which recognizes an individual who has made a significant and dedicated contribution to the sport of running in New Jersey.

American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame

In 2004, with the encouragement of Kevin Setnes, Dan, as the Executive Director of the AUA, established the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. It was created out of concern that the USATF Hall of Fame, as large as it was with over 300 inductees, mostly from the various track & field events, was not well suited to properly recognize the giants of ultrarunning at the highest level of elite performance. A clear example was the fact that Ted Corbitt, universally regarded as the “Father of American Ultrarunning,” and a former Olympic marathoner was not in the USATF Hall of Fame. Nor would it be likely that any of the subsequent American ultrarunning inductees ever be realistically considered for the USATF Hall of Fame, as it is almost exclusively focused on track and field events, with emphasis on success in the Olympic Games, which do not include ultrarunning. The initial inductees into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame were Ted Corbitt and Sandra Kiddy. Dan oversaw the hall of fame until 2020 when he turned it over to Davy Crockett.

In 2004, with the encouragement of Kevin Setnes, Dan, as the Executive Director of the AUA, established the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. It was created out of concern that the USATF Hall of Fame, as large as it was with over 300 inductees, mostly from the various track & field events, was not well suited to properly recognize the giants of ultrarunning at the highest level of elite performance. A clear example was the fact that Ted Corbitt, universally regarded as the “Father of American Ultrarunning,” and a former Olympic marathoner was not in the USATF Hall of Fame. Nor would it be likely that any of the subsequent American ultrarunning inductees ever be realistically considered for the USATF Hall of Fame, as it is almost exclusively focused on track and field events, with emphasis on success in the Olympic Games, which do not include ultrarunning. The initial inductees into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame were Ted Corbitt and Sandra Kiddy. Dan oversaw the hall of fame until 2020 when he turned it over to Davy Crockett.

Recent Years

Dan has had a 55-year running career including 32 years running ultras. With ultrarunning administration fully organized and working well with both the IAU and USATF, Dan moved on but continued to consult for years.

Dan has had a 55-year running career including 32 years running ultras. With ultrarunning administration fully organized and working well with both the IAU and USATF, Dan moved on but continued to consult for years.

He became one of the very few who successfully made running his career. He did it by establishing a running race timing business (DJB Event Consultants) and for years timed local road races almost every weekend. He also became a course certifier and was the course manager for the 1988 US Olympic Trials Marathon in New Jersey, along with other very prominent races, most notably the Philadelphia Marathon. He has been the official course measurer, and course signage installation manager, of the New York City Marathon for the past two decades.

Dan became an expert in logistics and operations for road races, triathlons, and cycling races. He served for ten years as the course director for the NJ Gran Fondo cycling event, which was voted by Gran Fondo Guide magazine as the #1 Gran Fondo event in the country 3 years in a row. In 2022 Dan continues to run, put on local races, and his passion is competing in adventure racing including mountain biking, canoeing, trail running, cross-country skiing, and orienteering.

Dan recently celebrated his 37th wedding anniversary to Joyce Hayes, a runner, and triathlete who was an age-group podium finisher at the Ironman distance Triathlon in Lake Placid, NY. Dan and Joyce ride together in over a half dozen Gran Fondo ultra cycling events each summer.

Dan’s running PRs: half marathon, 1:10:07, marathon, 2:31:13 (Boston 1979), 50K, 3:19, 100k, 7:52, 100 miles, 15:09:40, 24 hours, 135 miles, 48 hours, 223 miles, six days, 468 miles.

Dan Brannen’s Contribution to Ultrarunning

Ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy, wrote, “Without Dan Brannen, it is entirely possible that the IAU’s development would have been delayed, perhaps by decades. His work in USATF Committees ensured that the US Ultra championships and team representation happened.”

Ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy, wrote, “Without Dan Brannen, it is entirely possible that the IAU’s development would have been delayed, perhaps by decades. His work in USATF Committees ensured that the US Ultra championships and team representation happened.”

Ultrarunning Hall of Famer, Kevin Setnes added: “While a few people saw the importance of governance by a national governing body, no one possessed the foresight, saw the importance of, or had the political acumen to navigate the bureaucracy of TAC (USATF). Under Dan’s leadership, ultrarunning gained acceptance within the long-distance running body. While still fringe by its nature, the rules of competition, course measurement, and records helped legitimize the sport and gain its acceptance. Today’s recognized national championships and the formation of national teams are largely a credit to Brannen’s persistence.”