Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:52 — 30.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

The first certified 100 km race in America was held at Lake Waramaug, Connecticut, in 1974. Today it remains as the oldest 100 km race in the country and the second oldest American ultra still held. For many years in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, it was the unofficial national championship for the 100 km distance and the best ultrarunners in the U.S. made their pilgrimage to Lake Waramaug to test their abilities on the 7.59-mile paved road loop around the lake.

Before 1974, the 50-mile or 100-mile distances had been the America’s “standard” ultra distances. But most of the ultras held during the 1970s were of odd lengths. There were a few road 50 kms, such as those put on by the AAU in Sacramento. But in the New York City area, the hotspot for ultramarathons put on by Ted Corbitt (1919-2007), of the New York Road Runners, had a large variety of ultra distances during the 1960s and early 1970s. San Francisco had been the scene of multiple 32 milers. Racing around Lake Tahoe for 72 miles would become popular starting in 1975. No one had yet thought to put on a race that was exactly 100 km.

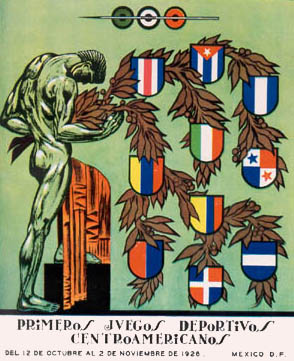

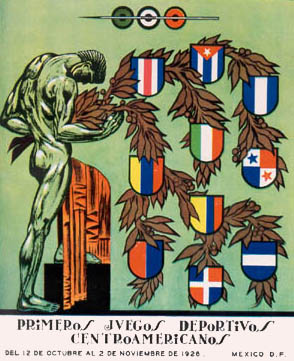

The Great Tarahumara 100 km of 1926

It was called La carrera Tarahumara, or the “Great Tarahumaran Race,” and was held five days after the games. It was hoped with the attention to this race, that the 100 km would be adopted by the upcoming Olympic Games. “They dreamed that their Tarahumaran countrymen would win honor for Mexico by thrilling the world at Amsterdam in 1928.” With Mexican victories, they hoped that it would help drive away racial lies about the Mexican people.

100 km Races Begin in Europe

100 km races began to be held in Europe as early as 1959 with the Lauf Biel 100K that was competed on a long road loop in Biel, Switzerland. Most of these European 100 km events started as hikes but opened up to runners. In 1974, nearly 2,500 runners and walkers finished the very popular European race. At least 14 100 km races were held that year in Europe. The fastest recorded 100 km times were usually split times accomplished by runners trying to achieve longer distances, such as 100 miles. In 1974, before America had a 100 km race, the world record of 6:42:53, was held by Ensio Tanninen (1936-) of Finland, who set that mark on an uncertified road course in 1972 at Järvenpää, Finland. The record on a certified track was 7:26:14, set by George Perdon (1924-1993) of Australia, in 1970, at Olympic Park in Melbourne, Australia.

America Was Slow to Adopt the 100 km Ultra

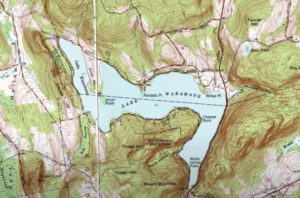

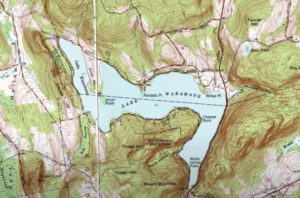

Lake Waramaug

The lake was described in 1860 as a quiet place that only had one road coming to the west side of the lake. The roads around the lake were first created and improved during the 1860s. A small hotel was operated there. “Lake Waramaug is a beautiful sheet of deep, clear water. Its length is nearly five miles and in form it is like the letter ‘S.’ For beauty of situation, it is unparalleled. On every side, high mountains meet the vision. Many of those who entertain summer boarders are wealthy farmers.”

Steamboats operated for decades, giving rides day and night around the lake starting in 1874. Fishing on the lake was one of the main attractions for visiting. The lake was stocked with bass, trout, and even salmon. The small village of New Preston sat a half mile from the south end of the lake. It contained 200 residents, a store, a blacksmith shop, a grist mill, a school and a church.

ice was free of snow. “It was interesting to see a horse and carriage going down the middle of the lake along a path plainly visible.” Large crowds would come from surrounding towns each winter when the races were held. In the summer, sailing races could be seen on the lake.

In November each year, the resort community shut down almost entirely. “Lake Waramaug has now a deserted appearance on account of the closed cottages and hotels about its border. This dreary season will come, especially when any locality is used as a summer resort almost entirely.”

Tragedy and deaths occurred at the lake. In 1901, two waitresses from New York City, working at the hotel, went missing. Their shoes and towels were found on the lake shore, and they both went into the water and somehow drowned. Their bodies were found in 18 feet of water, five feet from each other. That same week, during a picnic party of young people, Sheldon Edwards, age 23, was seized with cramps while in the water and drown before help could reach him. Drowning in the lake occurred nearly every year, most often when boats were overturned and people without life preservers couldn’t swim to safety.

Pleasure rides and a slower speed around the lake became popular in the coming decades. “A trip around Lake Waramaug is over dirt road, but on a dry day is well worth making the run around the lake in order to view the camps of summer residents.”

Runners Spotlight – Jack Bristol

In the 1970s, Bristol founded the Bethel Bananas Running Club. The logo on club running shirts read, “Boogie till ya Puke.” About Bristol, it was said, “Jack ran anything. It didn’t matter the distance, the type of terrain, or how many people were in the race. He always gave it his all. One mile, 100 miles, what’s a few miles among friends?”

Bristol started running ultras in 1971, competing in the National AAU 50 Mile Championship in Rocklin, California. He placed 9th with 6:39:50. He ran again in 1972, placing 5th with 6:27:22.

One of Bristol’s early ultras was the Metropolitan 50 miler, held in Central Park, New York in 1973. He finished 7th, in 6:15:27. That year he also ran the Two Bridges run in Washington D.C. The race was 36 miles. It started at the Washington Monument and went to Mount Vernon and back. Forty-nine runners were in the field. Bristol placed third. He had quickly progressed to be one of the elites in American ultrarunning.

The Founding of Lake Waramaug 100 km

The 1974 Lake Waramaug 50-miler and 100 km

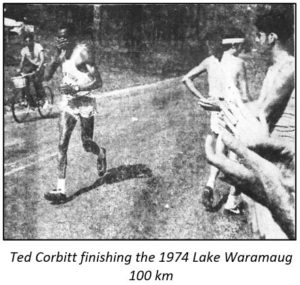

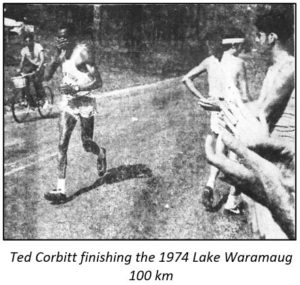

The first Lake Waramaug race was held on May 11, 1974. It was 52 degrees at the start and reached 70 degrees during the race. The course was held on a 7.66-mile pave-road loop circling the lake. The road was mostly flat, with a few gentle slopes and had very little automobile traffic. It featured both a 50-mile race and a 100 km race. Once you reached 50 miles, you had the option of continuing to finish 100 kilometers. If you did that, you would get credit for finishing both ultras.

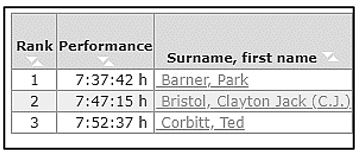

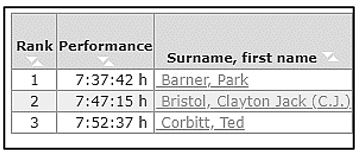

Twelve strong runners toed the starting line of this historic race. Bristol led the race at the marathon mark with a blistering time of 2:58. Park Barner (1944-) of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was about six minutes behind. Eight runners made it to the 50-mile mark. First was Barner in 5:55:30, second was Bristol in 6:06:23, and third was legendary Ted Corbitt (1919-2007), age 55, of New York City, in 6:11:27. The 50-miler required 6.5 loops and finished across the lake.

Corbitt said, “It was a great race. The course is beautiful, the traffic minimal. It is a moderately hard course, and I hope we can have the race every year.” He admitted that he was only in “fair condition,” and hoped to train harder for future races.

There were five others who made it to 50 miles during this inaugural year but did not continue. They were: Dean Perry (1950-), Lloyd Ryyslyainen (1949-2013), Phil Heath (1944-), Nathan Cirulnick (1930-2003) and Edwin Duncan.

Perry hoped with the success of the race that more ultramarathons would be established in Connecticut. About the experience of running 100 kilometers, he said, “You can’t beat the exercise.”

The Passing of The Torch

For Barner, it was the third year of his dominating hall-of-fame ultra career. Just six months later, he won the second American 100 km held on the C&O Canal, starting in Washington D.C. on the flat dirt surface. His winning time was 7:52:43. Milroy compared Barner to Corbitt and wrote, “A lanky, unassuming, ‘aw, shucks’ type of guy became a friend and student of Corbitt’s. The two men were similar in character, being noted for their quiet and modest personalities. They were not without their quirks; Barner, for instance, would typically shun the fuss of holding centre stage at races, yet often ran them in unmatched, garishly fluorescent-coloured socks – one orange, one green. Physically, Barner lacked Corbitt’s speed, and was much more of a ‘pacer’ than ‘racer’ in his approach to competition.”

Reminiscing back on Lake Waramaug in 1974, Barner said, “We always enjoyed going up there and staying at the inn. I ran 135 miles the week before Waramaug, 30 one day, 31 one day and a couple of 20s. I just liked to run, and I didn’t get tired. Nobody ever heard of running like that back then.”

Lake Waramaug 1975-1977

Barner won the Lake Waramaug 100 km again in 1975 and 1976 in 7:23:28, and 7:15:14, lowering his American record each time and then lowered it again in 1977 to 7:11:44, at Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania during snow squalls.

In 1977, the Lake Waramaug race doubled in size with 35 starters. In the field were the four fastest American 100 km runners, Barner, Bristol, Nick Marshall (1948-) of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, and Don Choi (1948-) of San Francisco, California. Choi blasted into the lead with a 6.5-minute gap on the rest of the front-runners at mile 20 and clearing the marathon mark in 2:53:48. Marshall recalled, “As Choi deteriorated, Marshall accelerated past him around 35 miles and went on to reach 50-miles in 5:42:31. Then he faded somewhat himself over the closing twelve miles.” Marshall, in his third year of running ultras, halted Barner’s win streak to three years, by pulling off the 100 km win in 17:17:06.

Lake Waramaug 1978

The 1978 Lake Waramaug race was referred to as “the top ultra contest in the northeast.” Fifty-six runners started. Several elite runners pressed hard, clocking sub-three-hour marathons. Frank Bozanich (1944-) tightened up but hung on from the 50-mile with in 5:14:36, which was less than two minutes off the American record. Roger Clark Welch (1942-2023) of Marshfield, Massachusetts, was the surprise winner of the 100 km in 7:25:37.

The first two women ran at Lake Waramaug in 1978, finishing the 50-miler. They were Connie Acton (1948-) from Connecticut and Sherry Horner (1955-) of Pennsylvania, with 8:05:23, and 8:41:23. Horner went on to beat the American 100 km record with a time of 10:55:33.

Howard Breinan, (1968-) age nine from Hebron, Connecticut, finished the 50-miler with his father in 8:58:28, making him the youngest finisher of an ultramarathon in 1978. (Breinan would continue to finish ultras into 2021.)

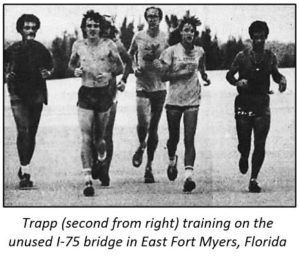

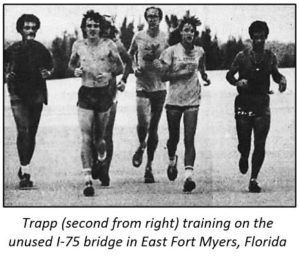

Runner Profile – Sue Ellen Trapp

Sue Ellen Trapp (1946-) was from Lehigh Acres, Florida. In 1971, at the age of 25, she was a new mom, was finishing dental school, and decided to take up running, along with her husband Ron Trapp, to get into shape for tennis, which she was highly competitive in. Her first race was Bay to Breakers 12K. She said, “I thought I’d just try it and it was awful.” But she continued and traveled with her husband to run various short races. She ran her first marathon in 1975 in 4:04 and then gained speed quickly. She won her first marathon later that year with 3:19 and continued to win and lowered her time to 3:04.

Trapp set her sights to run at Lake Waramaug in 1979. She was training 120 miles per week, which left little time for anything else. She said, “My legs feel like jelly,” after finishing an 11-mile workout. “It’s incredible how time-consuming this becomes. It seems like all I’m doing is working and running. After Lake Waramaug, I can become a human being again.”

Lake Waramaug 1979

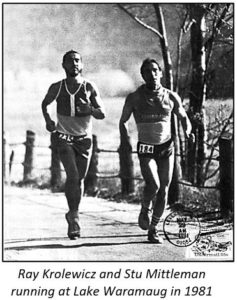

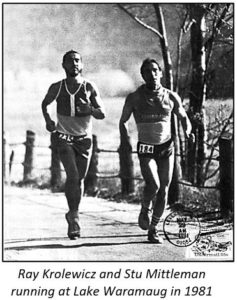

The 1979 Lake Waramaug 50 and 100, in its 6th year, grew to be a big-time ultra, with 120 starters. It attracted the greatest ultrarunners in the eastern United States. For many that year, including Ray Krolewicz, (1955-) of South Carolina, it was their first ultra attempted. At least six women started, including Sue Ellen Trapp. The entrance fee was $4, sent into Dean Perry.

The race started at a fantastic fast pace with Jack Bristol, Alan Kirik (1943-), and Martin “Marty” Kittell (1954-), of New York, running sub-six-minute-mile pace. Kittle and Kirik cruised through the marathon mark in 2:33:19 and continued an intense dual, “with them laughing as they each aggressively pushed the pace to try to lose the other.” Kittell finally cracked and Kirik broke the American 50-mile record by 12 minutes with 5:00:30 and then stopped.

Trapp, age 33, hit the marathon mark in 3:30 and the 50-mile mark in 6:55:30. She was one of the few that continued on to achieve 100 km. She broke the American record by 27 minutes in the 100 km, with 8:43:14, the second best in the world at that time. (Chista Vahlensieck, (1949-) of West Germany held the world record with 7:50:37, set in 1976 in Unna, Germany, on an uncertified road course). Roger Welch won for the second-straight year in 7:17:14.

Lake Waramaug Going Forward

Entering the 1980s, Lake Waramaug was the premier 100 km in America. Both the 50-miler and the 100 km were highly competitive, and Lake Waramaug was the site of many legendary performances and records for years to come. The 1980 race was battered by 60 mph wind gusts that caused several runners to actually hang on to the road guardrails to prevent them from being blown into traffic.

Ray Krolewicz became a fixture of the race, finishing the 100 km 27 times, with 11 wins. Barner finished the nine first Lake Waramaug 100 kms.

In 1991, the ultrarunning community was shocked to learn of Jack Bristol’s, premature death at the age of 42. He had not been racing ultras for the past seven years. The Lake Waramaug race continued and was renamed to “Jack Bristol Lake Waramaug Ultra Races.” In 2023, it ran for the 46th year, the second oldest American ultra.

Sources:

- Davy Crockett, “The Tarahumara Ultrarunners” https://ultrarunninghistory.com/tarahumara/

- Andy Milroy, North American Ultrarunning: A History eBook

- Lori Riley, “Lake Waramaug Ultra has endured as race organizers work to keep it alive.” https://www.courant.com/2019/04/28/since-1974-lake-waramaug-ultra-has-endured-as-race-organizers-work-to-keep-it-alive/

- Nick Marshall, “Ultradistance Summary,” 1977, 1978, 1979

- Litchfield Enquirer (Connecticut), Aug 14, Oct 30, 1879, Dec 16, 1880

- The Day (New London, Connecticut), Feb 18, 1890, Aug 8, 1934

- The Newtown Bee (Connecticut), Jan 24, 1896, Feb 21, 1896, Jan 29, 1897, Sep 15, Nov 10, 1899, Jan 18, Jul 5, 1901, Aug 1, 1902, Aug 21, 1903, May 22, 1908

- The New York Times (New York), Aug 18, 1904

- Harford Courant (Connecticut), Jul 6, 1901, Jun 14, 1914, Aug 10, 1934, May 8, 1974

- The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut), Aug 17, 1934

- The Miami News (Florida), Jan 25, 1979

- News-Press (Fort Myers, Florida), Apr 7, May 7, 1979

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 29, 1979

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), May 11, 1979