Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:34 — 23.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

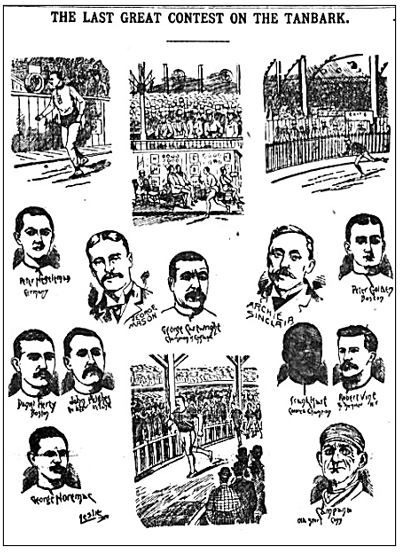

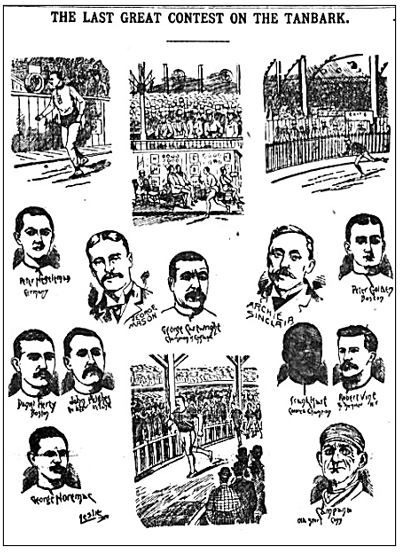

The New York City press was favorable. “Old Sport Campana, whose increasing years seem to add new vigor to his constitution, will start. He will celebrate his 99th birthday on the track.” He was confident that he would reach 550 miles before he retired from the sport. Everyone wondered what new antics he would perform during this race.

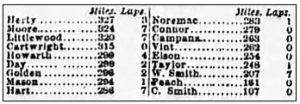

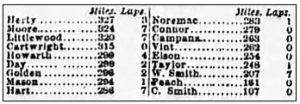

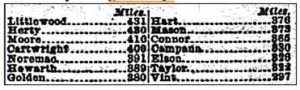

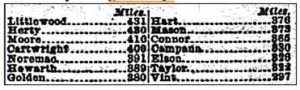

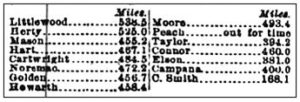

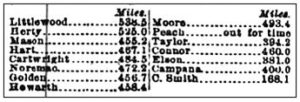

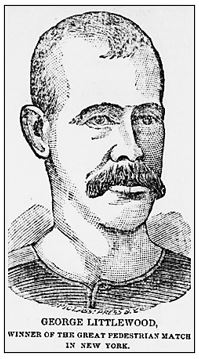

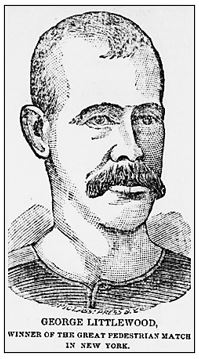

A bold prediction was made that George Littlewood (1859-1912), of England, would break the world record. “Probably no man alive today can beat Littlewood. He is a phenomenal pedestrian, and having a poor field to beat should win with ease.”

|

The Start

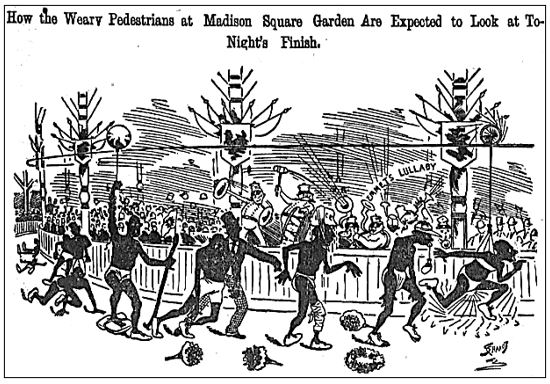

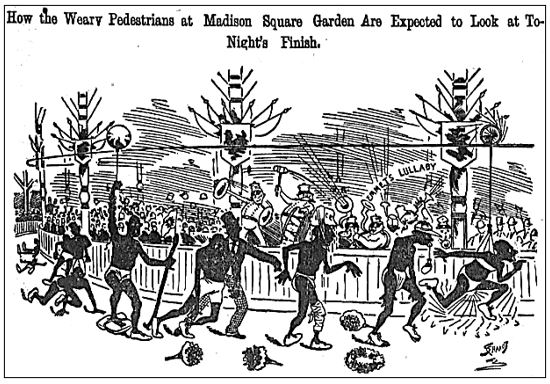

An hour before the start, Madison Square Garden was full, with 9,000 spectators, despite a howling blizzard that ripped through the city during the day. Thirty-six runners came to the starting line, led, as usual, by Campana, age 52.

At 12:05 a.m. on November 26, 1888, Campana led the runners across the line. “Campana who has been likened to a fragment of time, broken off the far end of eternity, got a big start and made his bony shanks play like drumsticks for a lap. He passed under the wire first.”

Through the first night, it became obvious why there were plans to have Madison Square Garden demolished and replaced. “The ring in the center of the garden looked as if it had been swept by a hurricane. Booths were overturned and the floor was flooded with melted snow, which had dropped through the crevices in the roof.” Littlewood, dressed in white drawers and an undershirt, with a red cloth around his neck and a toothpick in his mouth, reached 77.5 miles in twelve hours in front of about 700 people in the cold building.

After twelve hours, Campana had covered 60 miles. Campana complained that the scorers were rigging the race against him. “He went on again, with a blue nose, red cheeks, and open mouth.”

With 122 miles, Littlewood left the track for a long nap, dropping him to fifth place. He had drunk a bottle of beer that had gone slightly sour, and it upset his stomach. All runners who reached 75 miles during the first day could continue. The field was cut down to 24 competitors.

Day Two

Shortly after dawn on the second day, a “loafer” made an insult to Campana. “The Bridgeport centenarian always prefers paying value received, and he scrambled over the picket fence, and, after a short interview with the loafer returned to the track, leaving him with a black eye and a sadly troubled pride.”

Campana looked fatigued on the second day. His wife, Jennie, was not cooking his meals in this race, but from Bridgeport, she sent a telegram that told him not to lose heart. The Marquis of Queensbury, John Douglas (1844-1900), dropped in to watch. “He and a select coterie amused themselves for an hour by tossing dollar bills to Campana. He picked up the bills reverentially and then kissed the tips of his bony fingers to the English nobleman and continued on his journey. The wad of bills acted like oil on a rust wheel box, and the veteran outdid himself for a few minutes.”

Campana sent home $55 to his wife that he picked up off of the track. For each bill received, he knotted them on a cord that he wore around his neck, making a knotted necklace. His Connecticut rival, Alfred Elson (1836-1900), who was the same age as Campana, remarked, jealously, that spectators only gave bills to broken-down walkers. It was ironic that Elson was twenty miles behind Campana and in last place. Elson admitted that he would not refuse the bills if offered to him.

Day Three

At daybreak, the five leaders were all within twenty miles of each other. Before noon, Littlewood climbed into third place as other runners began faltering. Littlewood seemed to be the greatest eater among them. During the morning, he ate eleven lamb chops, washing them down with two large bowls of oatmeal gruel.

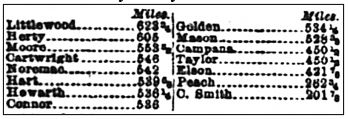

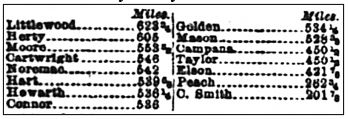

The runners continued to circle that track all day. Littlewood, eight miles behind, ran hard as dusk arrived and the gas and electric lights were seen through the “sickly atmosphere” of cigar smoke.

Day Four – Thanksgiving

The Thanksgiving spectators were dressed up. “There were Sunday coats and Sunday trousers, with store wrinkles still in them. There was a clean-shaven and freshly brushed air about the men, and the wives and sweethearts were numerous. Everybody was particularly good-natured and the peanut, popped corn, and refreshment stands did excellent business. The condition of most of the men was remarkably good. All are footsore and stiff, of course, but the hollow eyed, utterly exhausted look which usually comes about the fourth day was generally absent.”

Day Five

Littlewood retook the lead at 4:30 a.m., with 450 miles, increasing his lead to four miles by daybreak. But when he left the track at 12:30 p.m., a rumor circulated that he had fainted on the track and was taken to his hut. It apparently was not true, because he quickly returned to the track.

Campana continued to receive dollar bills from spectators. He sent home $55 to his wife that he picked up off of the track on the previous day. For each bill received, he knotted them on a cord that he wore around his neck, making a knotted necklace.

Littlewood completed his 500th mile at 109:56:30, only 38 minutes behind the world record held by Fitzgerald. “The crowd cheered, and the band played ‘We Won’t Go Home ‘Till Morning.’” As the evening progressed, more people came to watch Littlewood try to break the record.

The Final Day

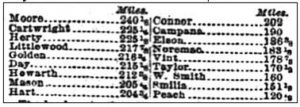

At midnight, Littlewood received an alcohol bath and a rubdown, and then was tucked in his bed for a two-hour nap. “His limbs were as clean as those of a racehorse and there was not a mark nor blemish on him. His feet were pink and white, like a baby’s and there was never a blister.” He gradually increased his lead to eighteen miles by dawn. Fourteen of the 36 starters remained in the race and ten still hoped to reach 525 miles, to claim a share of the gate receipts.

At 6:54 a.m., Littlewood caught up with the six-day world record pace as he reached 568 miles. “The contingent of British subjects which has infested the Garden since the race began, cheered, and the sleepers in the back seats awakened and joined in the applause, while the band played, ‘Hail Britannia.’” If he could maintain a 15-minute-mile pace to the end, he would win with the world record. He continued to either be cheered or hissed on the turns.

Campana reached 400 miles, in tenth place, during the morning, but was said to be in a crying mood. “One scorer named J. Harrison, was standing by his tally sheets when Old Sport came by. He was about to make a sympathetic remark to Campana, when Campana struck him with his clenched fist on the nose. ‘First blood’ remarked Campana as he resumed his customary jog trot. Harrison, having washed the blood from his face, met Campana once more and asked him why he struck him. Campana’s hands went up in answer, and both men clinched. The battle was short, sharp and decisive. Mr. Harrison was taken away. The crowd went wild with enthusiasm over Campana’s boxing encounter.” As he was running next to Herty, a man yelled, “Don’t lend him a cent, Dan.” “Quick as a flash, Campana’s fist left his shoulder, and the man spent the next minutes wiping the blood from his damaged nose.” His local newspaper was critical, writing, “His eccentric conduct injured his reputation.”

But Campana was smart enough to know how to keep the crowd on his side. “Campana raised a burst of enthusiasm by making a lap with a handsome baby in his skinny arms. The little one crowed joyously.”

Six-Day World Record

At noon, Littlewood was 13 miles ahead of the world-record pace. Manager O’Brien brought in the Fox Diamond Belt. It was put on exhibit in a glass case on a background of purple velvet and placed on a table at the scorers’ stand.

Back to Connecticut

Campana did not sail to England, as many reports claimed. Instead, he returned to Connecticut and before the end of 1888, competed in a 27-hour race in Birmingham, Connecticut, where he reached 120 miles, in fourth place. He was awarded a pie five feet in diameter. For 1888, he raced in ten ultra-distance races, totally 2,412 miles.

54-Hour Race in New Haven, Connecticut

In mid-January 1889, Campana competed in a 54-hour race held in Quinnipiac Rink, in New Haven, Connecticut. After 24 hours, he was in third place with 105 miles and was serious about doing well. “He ceased swinging his arms and shouting to the spectators around the track and had not stopped walking since the start.” He finished in second place, with 200 miles.

72-Hour Race in Brooklyn, New York

On the second day, “Old Sport kicked up his heels and ran around in ludicrous style that won him several greenbacks and a number of small coins from the amused onlookers.”

A curious reporter wrote, “It is surprising how Campana shows up at the various exhibitions given throughout the country. It has always been said that he is a very poor man, but no matter where there is a walking match, he manages to get there.” The reporter went to the race one evening and saw a man stretched out in front of a large stove. He was told that he was Old Sport. “When the men were called out on the track at midnight, he was the first one to get in place. There was no one at his side to receive his hat or coat. He threw them on the floor, depending entirely upon the honesty of the spectators to see that no one carried them off.” He asked, another runner’s backer, “How does he manage to get rest and get rubbed down. The reply was, “He attends to all that himself. In a match of this kind, he depends entirely upon what the owners of the place will give him. They know he will draw quite a number of persons on account of the queer manner in which he acts while on the track, and so he is presented with a few dollars to go on when the attendance is the largest. His only fault is that he entered pedestrian life when he was too advanced in years.”

On the final day, Campana ran when he wanted and rested when he wasn’t interested. “He frequently drained the contents of a beer glass ‘for a reviver’ while the spectators cheered him at each fresh outbreak. Campana finished in second place, with 280 miles, earning him only $23.75 for his effort. Samuel Day (1847-1913) won with 300 miles.

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part One

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Two

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Three

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Four

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Five

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Six

Sources:

- The Sun (New York, New York), Nov 22, 27-28, Dec 1, 1888

- The New York Times (New York), Nov 27, 1888

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Nov 22, 26-30, Dec 1, 4, 1888

- Wilkes-Barre Times Leader (Pennsylvania), Nov 23, 1888

- Pottsville Republican (Pennsylvania), Nov 27, 1888

- The Brooklyn Daily Times (New York), Nov 28, 1888

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Jan 27, 1889

- Reading Times (Pennsylvania), Nov 28, 1888

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Pennsylvania), Dec 1, 24, 1888

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Dec 2, 1888

- The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut), Dec 3, 5, 1888

- The Waterbury Democrat (Connecticut), Dec 22, 1888