Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:14 — 33.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

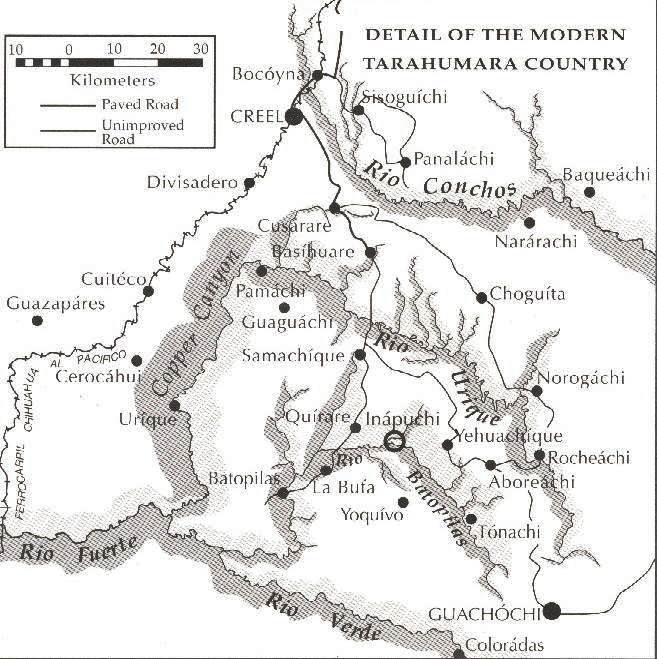

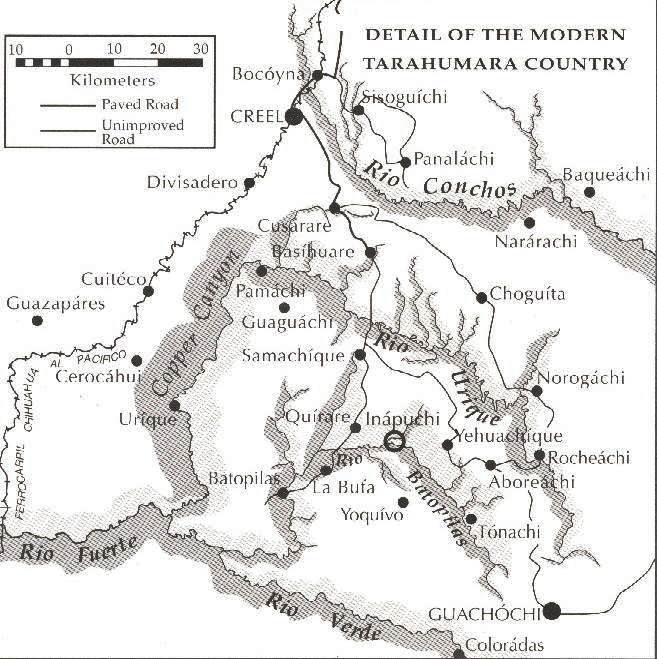

In recent years, the story of the amazing Tarahumara (Rarámuri) runners from Mexico exploded into international attention with the publication of Christopher McDougall’s best-selling 2009 book, Born to Run. Runners everywhere in 2009 naively tossed their shoes aside for a while and wanted to run like these ancient native Americans from hidden high Sierra canyons in Chihuahua, Mexico. Many other runners left the marathon distance behind, sought to run ultramarathons, and dreamed about running the Leadville 100, which exploded with new entrants.

In recent years, the story of the amazing Tarahumara (Rarámuri) runners from Mexico exploded into international attention with the publication of Christopher McDougall’s best-selling 2009 book, Born to Run. Runners everywhere in 2009 naively tossed their shoes aside for a while and wanted to run like these ancient native Americans from hidden high Sierra canyons in Chihuahua, Mexico. Many other runners left the marathon distance behind, sought to run ultramarathons, and dreamed about running the Leadville 100, which exploded with new entrants.

Readers of Born to Run think that the Tarahumara Indians made their debut running in America in 1992. Born to Run features their 1994 race at Leadville, Colorado. It has been falsely claimed that this was the first time that this indigenous people showed up to run outside their native environs. This is not true. Yes, the Tarahumara competed in America, in 1992, but it was not the first time that they displayed their running abilities in the United States. The Tarahumara competed in America more than six decades earlier when they made an even deeper impact on ultrarunning history.

The story of the Tarahumara was only half told by Christopher McDougall. Their early running stories have been forgotten and need to be retold. This is the story of the Tarahumara before Born to Run.

| Please consider supporting ultrarunning history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://www.patreon.com/ultrarunninghistory |

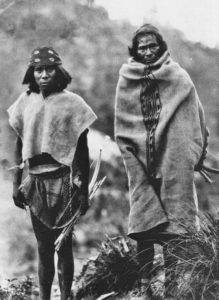

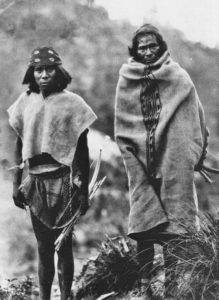

The Tarahumara are introduced to America

In 1889, America was first introduced to the Tarahumara by an American exploring expedition that traveled through Mexico and published a long fascinating multi-part article in many newspapers. The author, explorer, Frederkick Schwatka (1849-1892) wrote, “The Tarahumari tribe of Indians are not at all well-known, for I doubt if one reader in a thousand of this article have ever heard of them. The savage Tarahumari lives generally off all lines of communication, shunning even the mountain mule trails if they can. His abode is a cave in the mountain-side or under the curving of some huge boulder on the ground.”

Schwartka gave a brief mention of the Tarahumara running abilities, “In the depth of winter, with snow on the ground, the Tarahumari hunter, with nothing on but his rawhide sandals and a breech-clout, will start in pursuit of a deer and run it down after a chase of hours in length, the thin crust of snow impeding the animal so that it finally succumbs to its persistent enemy.’

Norwegian explorer Carl Sofus Lumholtz (1851-1922) lived among the Tarahumara for more than a year. In 1894 he published a book, In the Land of Cave and Cliff Dwellers and lectured to American Geographical Society about the people. “Mr. Lumholtz found the Turahumari unyieldingly opposed to the use of his camera on them until the fortunate day arrived when his photographing was followed by much-needed rain. Ever after the use of the “rain maker,” as the camera then came to be known, was sought as a favor.” He mentioned “their fondness for extensive foot contests, of which careful account is kept by a simple system of stone counters.”

But it wasn’t until 1905 that America started to have a true fascination with the Tarahumara Indians. Articles appeared across the country telling tales of “the most interesting tribe in the world.” They were described at that time as being a “savage” people of about 30,000 who seemed to be untouched by modern civilization and lived in the northern portion of the Mexican Sierra Madres.

The true name for this people was the Rarámuri. thought to mean “the running people,” although some Tarahumara have said it means “runner with the ball.” The Spanish, not understanding their language, named them the “Tarahumara”. In 1906 the public became truly fascinated in their culture when it soon was reported that they were amazing distances runners

The 1867 Women Tarahumara 100-miler

The race started at 6:35 a.m. “The whole bevy were off at the word go, amide the wildest excitement, and the betting commenced.” After the first loop of about seven miles, five women were together in the lead. The only stops they made were to accept prizes along the way, drink water or eat pinoli, “a simple gruel made of parched corn, ground and sweetened with sugar.”

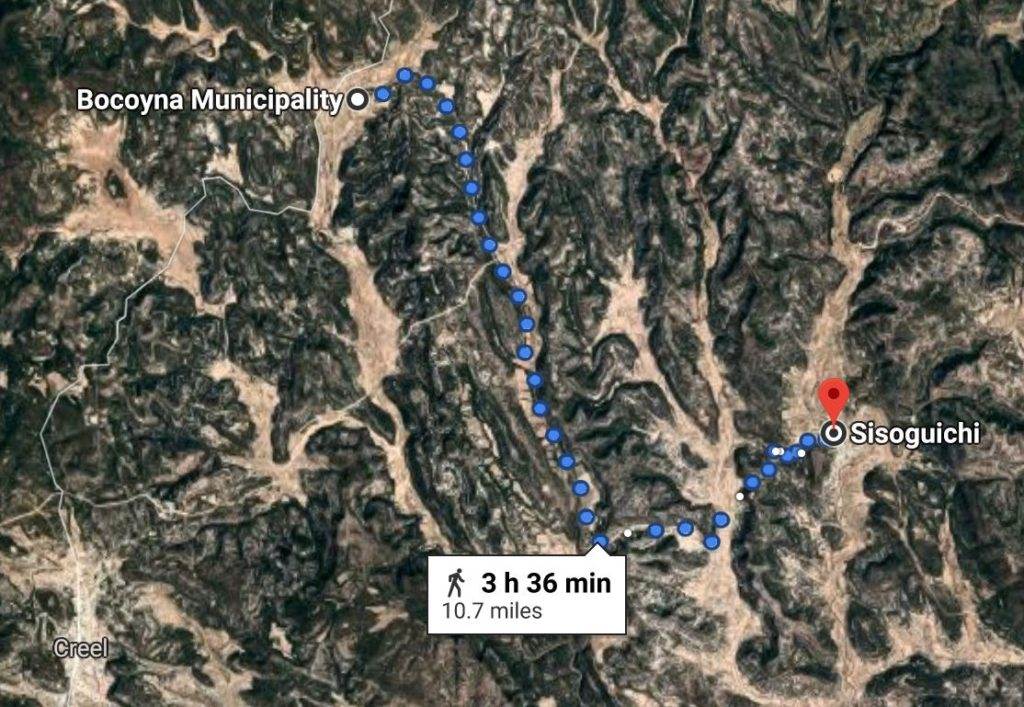

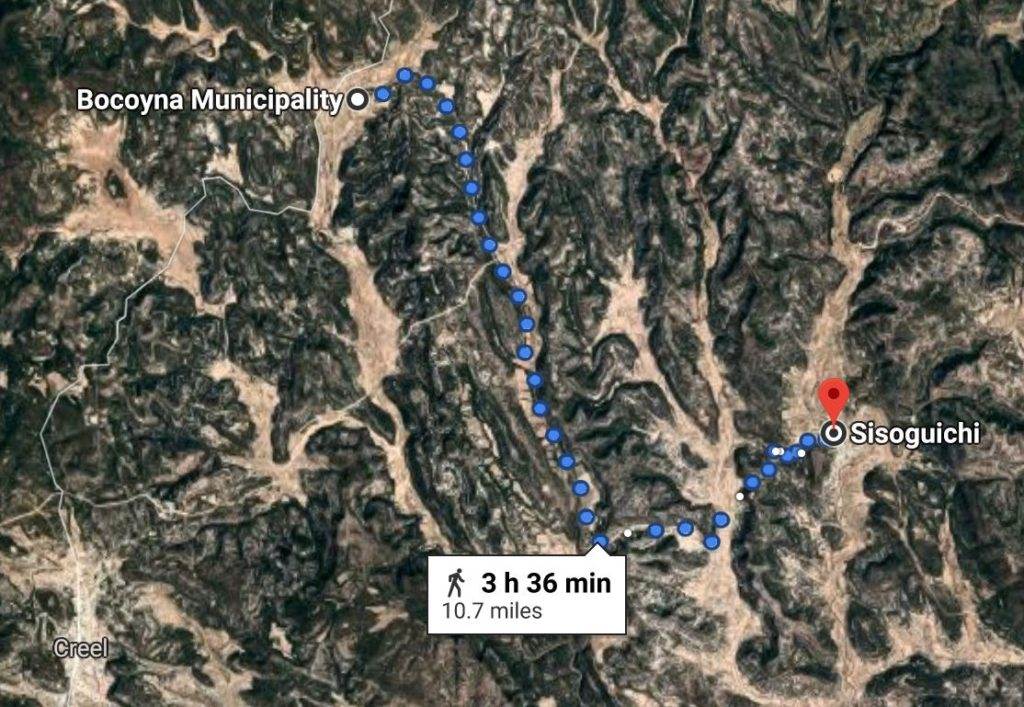

After about 92 miles only three women were left in contention, but by the last lap, the lone contending runner from Sisoguichi had fallen off the pace. The two winners were from Bocoyna, and were “received with the loudest shouts of joy by their towns people.” The women finished in 13:25. One of the women who finished had given childbirth just ten days earlier. Heavy betting took place. Horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, cats, dogs and other items changed hands. At the finish nearly everyone was “on the ground drunk.” This is the earliest known 100-mile mountain trail race, which was held 110 years before Western States 100. (Note: The distance of this 1867 race was likely short well of 100 miles just as the Westen States course in its early years was only 89 miles.).

Annual 140-miler in Sisoquichi

The Tarahumara held a 140-mile race annually in November at the town of Sisoguichi. The event consisted of eight 17.5-mile laps. In 1905, several runners covered the 140 miles in 30 hours. The contest did involve running. This description was given, “There were four runners on a side and each runner was handicapped by having to take with him a wooden ball which had to be kicked along the ground in front of him for the whole distance without once being touched with the hands.”

One observer reported, “A foot race among the Tarahumara Indians is a most picturesque scene, especially after nightfall, when the course is lit up by flaming torches carried by the eager friends of the runners, who steadily pursue their way, the only silent people in the excited crowd. How in their weird fitful light the men contrive to keep the ball in view is a mystery. One would think that so small an object would be lost in the flickering torchlight, but Indians have wonderful eyes as well as wonderful muscles and somehow the ball survives all perils and is there at the finish.”

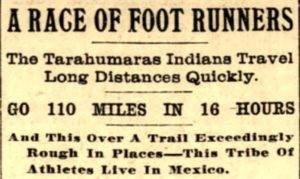

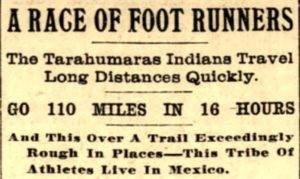

The 1906 mountain trail 100-miler

An historic race was held from Bocoyna to Minaca and back, 110 miles on “exceedingly rough” trails over the mountains. William Demming Hornaday (1868-1942), an American journalist, and the publicity director for the National Railways of Mexico, was there to watch this race and reported that the Americans collected a purse of $100 for the winner. This created great interest among the Tarahumara and at a council of members of the tribe, two of the fastest runners with great endurance were selected to race. Wagers were made both by the Americans and the Tarahumara.

American readers wondered how this newly discovered people could be “super human” runners. At that time it was said that the Tarahumara had great lung capacity and that they “adapt their movements to a long-gaited trot that seems slow to the casual observer. They have the faculty of recouping their strength quickly.”

Other Early legendary Tarahumara ultra-distance runners

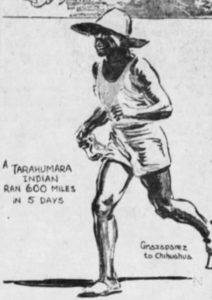

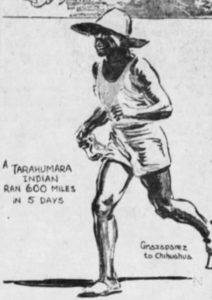

The Mexicans told a tale that a few years earlier, a commander of Mexican soldiers was in the area and needed an important message delivered to a town more than 50 miles away. A Tarahumara runner took on the task, delivered the message and returned within 17 hours. He then slept three hours, and took another message 150 miles away, running the round trip in three days. Others said he ran 600 miles in five days. Exaggerations were of course made, but the result was that the word got out about the Tarahumara runners as early as 1906.

One early report included, “They have frequently been known to run down from the mountains for forty or fifty miles to some town or village in the State of Chihuahua to dispose of some piece of handicraft of crude construction, which hardly bring more than fifty centavos. They can continue in that peculiar gliding dog trot, one of the most characteristic movements on earth, from sunrise to sunset, without stopping for food or drink.”

G. C. Terry reported to the Manchester Guardian, “Half a dozen men will take part in the chase. They head off the animal, taking up the pursuit in relays, until finally the poor beast, running in ever-narrowing circles, drops from sheer exhaustion. They also chase and capture the wild turkey in the same fashion.”

Around 1924, a match race that took place between the champion of the Yaquis and the champion of the Tarahumari in Chihuahua, Mexicso over a distance of 90 miles, across mountains, streams and “rough, broken ground.” They finished in almost a dead heat in 11 hours 15 minutes, with the Tarahumara just ahead. Wagers were made between the tribes, and the Yaquis lost a great amount of goods.

The Tarahumara run 10,000 meters in Mexico City

Jesus Antonio Almeida (1885-1957), the governor of the State of Chihuahua, was a Tarahumara by birth but not raised in the tribe. He witnessed a Tarahumara race in a local village during June 1926. The race was competed by women over 70 miles. About thirty ladies ran and the betting was furious. Many Tarahumara lost their life possessions as the result of their bets. He reported, “The Tarahumara is a gambler, and during the feast days, when a great race is announced, the men and women will bet even to the last blanket.” The race started a 5 p.m., concluding at 7 a.m. the following morning. Two women finished the 70 miles in fourteen hours.

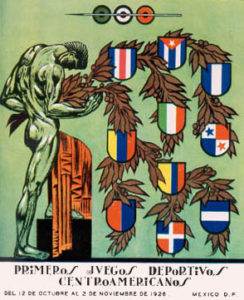

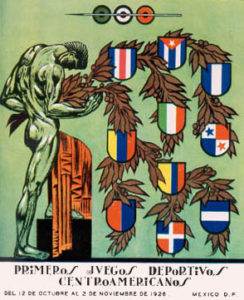

Governor Almeida was very impressed with the running talents of the tribe and believed it was time for them to compete for Mexico. The inaugural Central American and Caribbean Sea Games, the first international sporting event organized by Mexico, was being held at high altitude (7,500 feet) in Mexico City starting in mid October, 1926. These games were a regional Olympic initiative to promote interest and participation in the upcoming games. Fourteen nations were invited to participate but only Mexico, Guatemala and Cuba came.

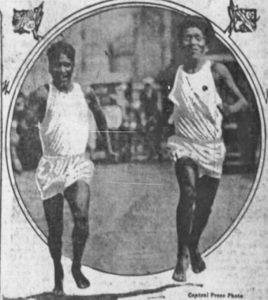

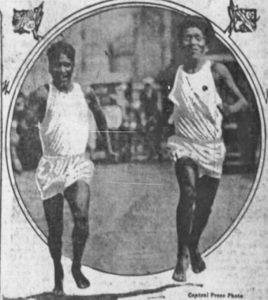

Almeida quickly entered two Tarahumara men in the 10,000 meter race. The runners were Tomas Zafiro and Jose Nevarez. They had been reluctant to leave their villages but agreed to run. An engineer, Carlos Peralta took them to Mexico City. Navarez did very well in the preliminaries, running in both the 10,000 km and a modified marathon. They both ran barefoot in the 10,000 km finals and everyone was astonished when Zafiro won with a time of 36:05.

The Great Tarahumaran Race

Governor Almeida and the President of Mexico, Plutarco Elias Calles (1877-1945) wanted to showcase the newly discovered Tarahumara running talent on this world stage. After the 10,000 meter race, Governor Almeida asked the Tarahumara men to stay and run in an exhibition 100 km race after the games were complete.

The terribly homesick runners declined the invitation. It was told, “Nothing made them happy. They wanted to see their babies, their children and the women folk who had been left behind. Of course they had been interested in the magnificent sights they had seen in Mexico City, the tall buildings and automobiles, but when asked to enter more races they shook their heads and turned their faces towards their glorious old mountains and forests.”

President Calles told them that it was their patriotic duty, but the men still weren’t interested. Finally the president of Mexico promised that he would give them schools for their children and that got their attention. But the runners would still be away from their farms, fearing the loss of their corn crop. The governor asked about the value of their crop. The two said after selling their crop, they would be able to buy thirty yards of white cotton cloth each. Almeida promised them that amount to appear. They became convinced and said, “All right, we will run.”

The 100 km race was held on a highway from the silver mining center Pachuca to the stadium in Mexico City. Tomas Zafiro ran along with Leoncio San Miguel. A third Tarahumara, Virgillo Espinoza, also competed. The race began in the dark at 3:05 a.m. The governor of Hidalgo and the mayor of Pachuca were there along with a large crowd to see them off.

“The three ran down a highway illuminated by the white rays of car and motorcycle headlights. Crackling firecrackers broke the usual silence. A caravan of cars, motorcycles, and riders on horseback followed the runners. Their bell-laden belts jingled in the night, marking a steady rhythm on their quest to race to Mexico’s capital city.” They seemed to run at top speed for an hour before their first stop for a few seconds. The Tarahumara were clad in white sweaters adorned by ribbons of red, green, and white, the colors of Mexico. They drank pinole, their native drink, a liquid made from ground corn. They also chewed the entire way on peyote, at cactus with psychoactive properties that they believed had healing properties

After a couple of hours, Virgillo was being left behind and was soon seen to be limping. The judges following the runners called to the boy to abandon the race. He first refused but an hour later was forced to stop. He was suffering from a sprained knee.

The people in the villages along the highway to Mexico City lined the road to cheer them on to the City. They shot off firecrackers, cheered, and some joined in to run with them for short distances. Church bells tolled bringing out more spectators. The two Tarahumara suffered from fatigue and cramps, but pushed though it, consuming 300 grams of pinole, several sandwiches made from tortillas, frijoles, and several oranges.

As they run toward the National Stadium in Colonia Roma, in Mexico City, thousands of people cheered them on. Their escort caravan swelled to 200 cars. Zafiro and San Miguel entered the stadium packed with thousands spectators at about 12:35 p.m. and ran three laps around the track, finishing at 12:42 p.m., tied for the win of 9:37. It was thought to be a world record. (Actually, the fasted known road mark at that time was accomplished by a professional, Emil Anthoine of France who ran 100 km on the Paris-Troyes Road in 1904, in 7:25. Their mark was likely an amateur road world best at that time by about 15 minutes.)

A writer present called the Tarahumara “super athletes.” He had seen marathon winners topple across the finish line exhausted, but not the Tarahumara. He wrote, “They made an extra circuit of the half-mile track and came to a halt in front of the box occupied by President Calles to receive from his hands the prizes they had trotted 100 kilometers for. Trained medical eyes watched the Indians, ready and almost eager to catch the first sign of exhaustion. But their eyes saw only a slight heaving of their broad chests.”

College athletes at the games were astonished. Some people tried to contend against their accomplishment with arguments that the Tarahumara received massages during the race by Red Cross ambulance men, which some considered receiving outside help.

Zafiro and San Miguel became national heroes. “The Tarahumaran runners served as icons of Mexico’s efforts to build a new post-revolutionary national culture. They seemed to have stepped from a mural depicting Mexico’s long-oppressed native masses as the heroic paragons of a new stable, just, and integrated society.”

1927 American interest

The accomplishment at Mexico created more American interest in the but they still did not get worldwide attention. The Dallas Morning News wrote, “What is believed to be one of the most remarkable running performances in sporting history was witnessed today in Mexico” They were called “the greatest long-distance runners in the world.”

The Tarahumara village races

In 1927, Governor Almeida gave a detailed description of their races in their villages. “The famous races are run over a stipulated course and the racers carry a medium-sized wooden ball, which they run and kick as they speed along. During these races the runners have their heads ornamented with feathers of the chaparral-cock, and in some parts of their territory with feathers of the peacock. Many of the runners have their legs ornamented with chalk and wear belts to which a great number of deer hoofs, beads or reeds are attached, to make a great deal of noise.”

“The women, as the runner pass them, stand ready with dippers of warm water, or pinole, which they offer them to drink and for which they stop for a few seconds. The wife of the runner may throw a jar of tepid water over him as he passes, in order to refresh him, and all incite the runners to greater speed by cries and gesticulations.”

“Their races consist of kicking a ball with their toes. The runners are clad only in a loin cloth and wear sandals (huaraches) on their feet. The distance may be from five to fifty mile circuits in length. The first four or five circuits are run at high-speed, but that speed is never held up, although once they get into a certain stride, they keep it constant. Good runners make from fifty to sixty miles in six to eight hours.”

“Women run their own races, one valley against another, and the same scenes of heavy betting and excitement are to be observed. The women do not toss the ball with the toes, but use a long two-prong stick, with which they propel the ball forward. It is a strange sight to see these fleet stalwart amazons racing by with astonishing perseverance.”

Tarahumara games

A favorite extreme game taken part by the Tarahumara is called palillo or tacuari. It has similarities to lacrosse. It involves carrying or throwing/hitting with a three-foot oak stick, a wooden ball the size of a baseball. Instead of a stick with a mesh, it is all wood with the end in the form of a spoon. “But none of these hundred yard fields as are used as in the modern namby-pamby game of lacrosse.”

The field can be miles long over mountains and through ravines. The goals could be at the competing villages. The entire countryside is in bounds. As many as 20 players can be on each side. The only constraining rule is that the ball cannot be touched by the hand unless it falls in the water or is stuck in rocks. On a pass, the ball is tossed into the air and batted with the stick with one arm. A good hit travels about 60-70 yards. It is typical for players to come away with cracked skulls and getting beat up pretty bad. The team wins when the ball arrives at the goal and the game can last for multiple days.

Racial bias

As can be expected, racist comments of the era surfaced about the people. Typical American racist stereotypes that Indians were lazy and drunk emerged. It was written in 1927, “The Tarahumaras are quite satisfied to live to themselves in blissful idleness. Generally speaking, they are regarded by the rest of Mexico as a lazy, decadent race, little concerned in the progress of civilization except as it may threaten to disturb their repose. The compelling desire to stub their toes upon the wooden ball seems to be the only thing that will prod them out of total inaction. So far as other thing go, ‘as lazy as Tarahumara’ would appear to be a phrase implying complete lack of enterprise.” Consuming their native drink, tesguino, or “corn beer” which was regarded sacred, was criticized and made fun of. “Inspired by tesguino, the Tarahumara will run any distance and kick anything within reach.”

Such hateful comments were countered in an El Paso, Texas, newspaper with, “Tarahumara Indians are said to be so degraded that they mind their own business and take care of their families. Civilization ought to do something about this.”

The Tarahumara plan to race in America for the first time

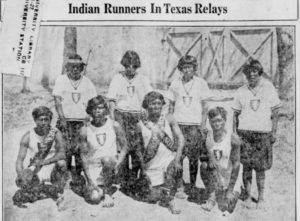

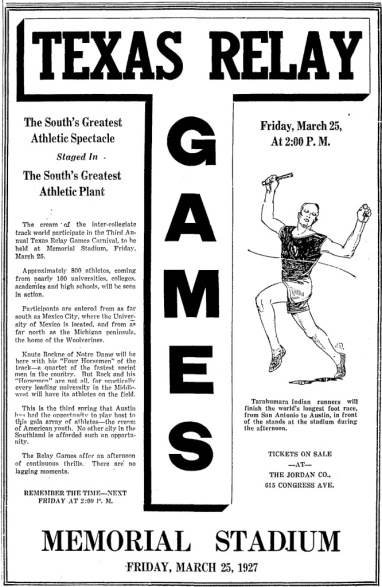

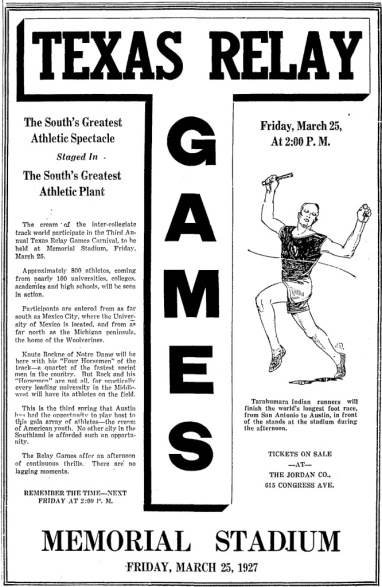

In early 1927, Austin, Texas announced plans to hold an 82-mile run from San Antonio to Austin, featuring three Tarahumara Indians runners. “Famous for their ability to run almost incredible distances with little rest, the Tarahumaras for years spurned offers of money and jewelry to brave the mysteries of civilization.” The race was part of the “Texas Relays” put on be the University of Texas. They mentioned, that “the Indians, although wearing regulation track suits, will race with their hair hanging to their shoulders.”

Many wondered and speculated how the Tarahumara would fare running outside Mexico for the first time. “In the lower levels of Texas, it is believed the Indians should be able to do much better. They are expected to have little trouble in annihilating distance records.” Some Americans were fearful that Mexico would gain an advantage at the next Olympics by including the Tarahumara. They felt comfort to know the Tarahumaras couldn’t bring their tesguino across the border into Texas and that their bare feet would be running on hot pavement instead of hard-packed dirt. But then it was reported that they could protect their feet with home-made sandals made from goatskin with leather thongs to wrap around bandaged ankles.

A New York Times sport columnist who was a Tarahumaran skeptic wrote, “This time they will run a distance measured in English miles and they will be timed by a split second watch, though, for that matter, in an 82-mile race, an alarm clock would do just as well.” But he still believed that “civilized” whites could easily beat the Indians if they wanted to run that distance.

The Tarahumara race trials

Upon receiving the invitation to compete, Mexican officials immediately started to train candidates for the event. They felt with this new venue, they could further prove doubters wrong. A Mexican newspaper predicted, “The Tarahumaras would garner a resounding triumph in Texas that would make Mexico famous in every corner of the world.” And said, “the name of Mexico would echo around the globe.”

On February 27, 1927, in Mexico, fifteen Tarahumara villages competed with 60 athletes to identify three men and three women to send to Texas to run in the 82-mile and marathon events. The elimination trials created great excitement among the Tarahumara, developing “sharp rivalry among the different villages.” The event became the biggest race ever held up to that time among the Tarahumara. In the main event, twenty-six Tarahumara men ran in a 91-mile race and three men were selected to run the 82-mile race. Women competed in the 45 km distance but their times were not considered “very extraordinary,” with 16-year old Juanita Paciencia winning with 4:46. The final runners were chosen. Mexican authorities were still uncertain if they selected the best runners of the tribe because they believed the best runners were never seen anywhere near the villages.

The men eventually selected were: Jose “Johnnie” Torres, 24 from Bocaina, Tomas “Tommie” Zafiro, 38 from Creel and Augustin “Gus” Salido. After returning from Mexico City, while training, Zafiro had unofficially broken his 100 km record, with 7:25 in a test run. Torres was considered the Latin-American 5000-meter champion. Salido was considered as good as the other two especially at longer distances. The women were just young girls. Lola Cuzarare, age 18 and married. She had no last name so took the name of her village. Juanita Cuzarare was 14 year old and Juanita Paciencia, was 16.

The tribe elders were not in favor of the whole undertaking but did bid farewell to the group leaving their villages and gave them their blessing with tribal rites.

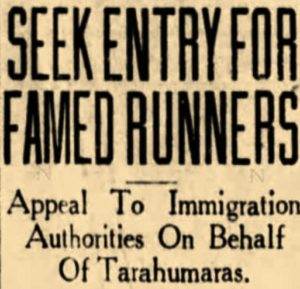

The Tarahumara arrive in Texas

Newspapers mocked this immigration controversy. “There could be no possible danger of letting in the Tarahumara Indians for it seems that nobody at present in the United States would find his job endangered by their competition. Nobody in America right now is making a living doing 60 miles running stunts at the rate they achieve.” A day later everything was resolved with the help of Senator Earle B. Mayfield (1881-1964) of Texas. The runners would not enter the country as immigrants, they would enter solely to take part in athletic events and were under the authority of the department of education.

On March 21, 1927, a party of ten Tarahumara crossed the border into United States to compete on US soil for the first time. The ten were six runners, an interpreter (Juan Zavala), a trainer (E. F. Perez), a chaperone, and a manager (Thomas Rodriguez). Mexico provided $1,500 for expenses. The men would run in the 82-mile race and the women in the 26.2 marathon. While on a train to Austin, three of the runners suffered minor burns on their bare feet from steam heating pipes in the pullman car. When they arrived at the Austin station they came off the train clad in the native dress, carting a huge store of supplies wrapped in “gaudy blankets.” A throng of newspaper reporters and curious onlookers met them.

Tomas Zafiro was interviewed by the San Antonio Light. Through an interpreter he said, “We begin to run when we are ten years old. I started in my native village of Creel. First, I hardened my feet by kicking a ball about. This ball being made of oak and called “umaca.” I won my first three races easily. We do not look upon our running as a business, but do it only three times a year at our great games, especially on the day of St. John, besides running, we play the “Palillo” which I think is the forerunner of your golf game and dance the “Pascole” a dance in which we use masks to cover our faces.”

He continued, “It was on these occasions that I won my races. Then I ran continually against the other boys of the village. We run so much there, that we can tire a deer after a chase of half a day or so. Many times five of us see a deer and run after him. When we run, we carry a girdle of bells about our waist and a piece of sugar cane in the hand, in order to keep a better stride. This run to Austin is not very difficult. I believe as many times we run much father. I expect we will make it in from thirteen to fourteen hours. We do not run for money but for the pleasure of it.”

The next day, the men with their manager Rodriguez, took an automobile ride to San Antonio, to preview the course backwards and to get ready for the start there very early the next morning. The road was hard-surfaced most of the way and in places covered with rough gravel. The runners shook their heads dubiously as they examined the highway, knowing that they would need to run in their sandals. Salido had never seen an airplane before and when one swooped down near the car he “became consumed with fear for the majestic birds soaring above him.” During their trip they stopped at shops and a store owner insisted that they select statuettes for free. They were very pleased and chose small black and white cows. Their spirits were very high. They prepared for their run by drinking herbal tea, anointing their bodies with oil, uttering “certain lucky phrases,” and then retired to a private room to pray and get some sleep before the early start.

Racial comments, that are disgusting to us today, appeared in some newspapers. A sports columnist for the Austin Statesman let readers know that the “redskins” would run from their “Alamo wigwam” in San Antonio to Austin. He said that the automobile that went along would not carry any “firewater.” He remarked that the women runners were too young to “be properly called squaw.”

The race from San Antonio to Austin

Rodriguez woke the runners at 2:30 a.m. and they were taken to a cafe for only coffee. Other nourishment would be given to them once they started. A little after 3 a.m. they appeared ready at the city hall steps and stepped into a circle cleared for the camera battery. They looked like bronze statues despite the motion picture photographers’ calls for some action. They were told to “get on the mark” for picture purposes. The milling crowd was caught unprepared for their get-away.

At 3:19 a.m. the race from San Antonio to Austin began. It was actually just a Tarahumara exhibition. No U.S. athletes were in the race. But the event was the central event of the Texas Relays. The Austin paper wrote that “it is truly a landmark in athletic history in the world, as it is the first race of its kind ever to be staged in this nation.” 2,000 spectators came out early to witness the start. “There was a mad rush in the wake of the runners they started. A dozen boys set out on their heels to run with them as far as they could. The Indians were off in a steady trot, bells attached to their waists tinkling, bambo staves swaying in unison.”

The running method of the Tarahumara seemed odd to observers. They did not run on their toes, they did heel strikes and pushed off from their mid-foot resulting in a very short stride. Little or no strain was thrown to their calves and no rise and spring from the instep and toe. The style seemed surprisingly easy and rhythmical. It was described as a shuffle and a glide, the feet barely leaving the ground.

The halfway point was reached at Hunter where they reached in less than seven hours at 10:05 a.m. and soon passed the 50-mile mark. Torres and Zafiro were in the lead with Salido a mile or so behind. Salido was soon attacked by stomach cramps and slowed, two miles behind. Rodriguez made the two in the lead slow down, hoping Salido would catch up. But when they arrived at Kyle, the 100 km mark at noon, Salido was far behind. He arrived there two hours later, collapsed, and was then brought by automobile to Austin.

Torres and Zafiro didn’t show any signs of weakening and continued along the road that was filled with cars, crowds, and motorcycles that rode along with them. They slowed to ten-minute miles. “Eight miles out of Austin, the road became almost impassable. Handkerchiefs had to be tied over the Tarahumara’s mouths to make breathing possible. The gas and exhaust pipes were almost disastrous to the runners.”

Their interpreter, Juan Zavala, an older runner paced them at times, trying to keep their morale up. He lifted his hat as applause came from the crowds. One observer wrote, “The runners were greeted along the road by the Mexican population enthusiastically as well as the Americans. The Mexicans would rush to the runners with gifts. One man gave each of the boys a plaster of Paris black and white cow, while an old water man emptied his pockets of coins into the hands of the runners. This is the custom in Mexico as the runner passes through the villages.” The runners showed their appreciation by slapping their chests and waving their arms.

They passed a “deaf and dumb” institute where every child was gathered on the lawn applauding. Jaun took off his hat and made a gracious bow. Whistles began to blow as they neared Austin. The streets were lined with “Applauding multitudes.” Two “motor policemen” met the runners five miles out of town and were “life savers” for the runners because the crowd had jammed the way ahead.

As they neared the stadium, Zafiro grasped a letter in his hand given to him from the San Antonio major for the Texas governor. He held it high as they reached the stadium grounds. Torres, Zafiro, and their pacer Juan ran three abreast around the track. Juan dropped out and let the two rushed through the tape covering what turned out to be 89.4 miles in 14:46 to a warm greeting of about 500 of the 10,000 spectators who had stayed around after the rest of the events were over. Zafiro and Torres finished in nearly perfect condition except for feet that were cut to shreds by the asphalt.

The University of Texas officials failed to provide any sort of trophies to the victorious runners. They were introduced separately to the crowd and received a round of applause, but it was evident from their expression on their faces that they had anticipated some sort of reward.

The women’s marathon

The women’s marathon that also run that day, it turned out to be 28.5 miles. They started in front of the American Statesman newspaper building at 11:34 a.m. Lola had been very ill before leaving Mexico and the manager, Rodriguez, had given strict orders for her not to run before he left for San Antonio with the men. She disobeyed him and toed the start line. They wore their native sandals and carried cane poles about four feet long and were paced by their trainer and chaperone who rode in cars.

The Texas race impact

It was written that In Mexico “the foot runners reigned in Mexican’s imaginations as the heroes of a new nation rising from the ashes of more than a decade of civil war.” Some predicted that Zafiro would break the Olympic marathon record.

Before the Tarahumara runners left the United States, many offers poured in from theatrical promoters to create plays and movies about the Tarahumara. Others wanted to take the runners to their cities for running exhibitions. Large amounts of money could have been made. But Rodriguez said, “We are not out to capitalize in dollars and cents on the Tarahumara running ability. They have willingly and graciously consented to come here and give an exhibition of their running. They have accomplished their purpose and are happily on their way back to their homes, where their loved tribesmen are anxiously awaiting their return.” Rodriguez recognized that they would be recognized as heroes. “A man is not great in his own country until he has gone away and made a name for himself, then he will be the lion of the hour. It is the same in the Sierras.”

Kansas Relays

By the time the runners reached the border at El Paso, it was announced that the three men would return to the U.S. in a month to run at the Kansas Relays to be held in Lawrence, Kansas on April 17, 1927. They would run in a race from Kansas City to Lawrence, a distance of about 51 miles on a course that wouldn’t be hampered with thousands of curious motorists’ cars. They had agreed to run if they could first return and see their families for a few weeks.

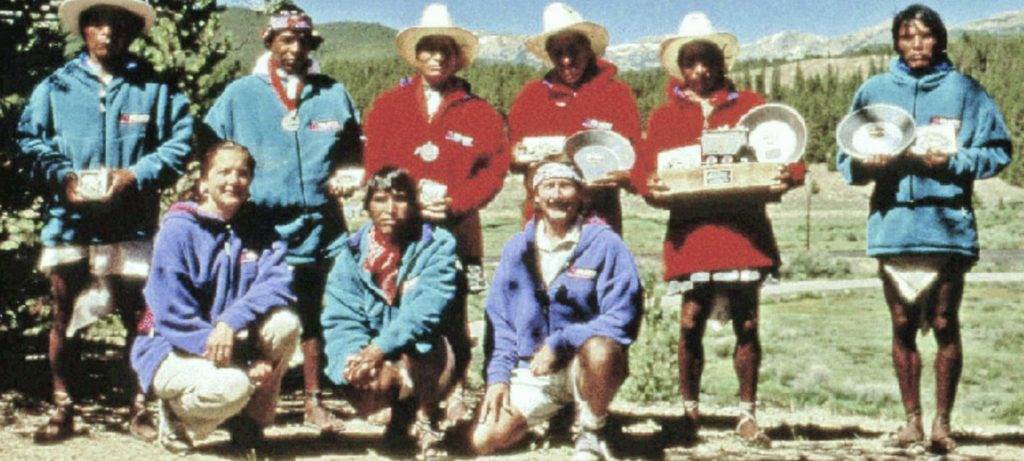

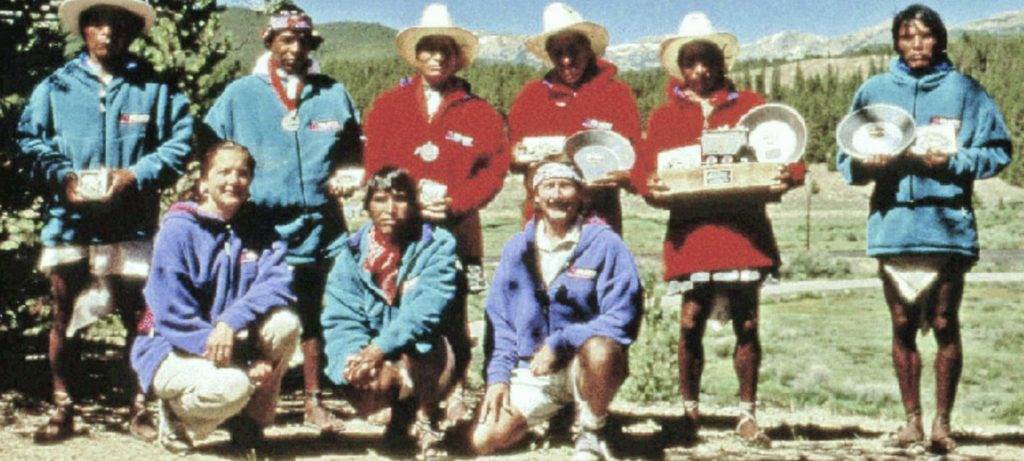

A couple of days before the big Kansas event, the Tarahumara arrived, three men and three women. They stayed at the Haskell Indian school. It was reported, “The Mexican runners were in fine spirits this morning and were pleased with the weather conditions. They hope that it will remain cool. As soon as the Indians reached Haskell last night they removed their leather shoes, the second ones they had ever worn, put on their sandals and ran around the Indian school track several laps to limber up their muscles.”

The format for the Kansas event was similar to the Texas relays. The men would run 51 miles from Kansas City, ending up at the Kansas university stadium and the women would run a 29-mile marathon from Topeka to the stadium.

Five men started on April 23rd including Purcell Kane, an Apache from Arizona and Burt Bertah a Navajo. Jose Torres was the hero, finishing 51 miles in 6:46:41 which was thought to be a world record. (It was an impressive time, but the world road 50-mile best at that time was held by Arthur Newton of England, with a time of 5:38 set in 1924 on the London-Brighton Road. In 1880 Dennis Donovan of Massachusetts ran 50 miles in 6:18).

Zafiro, the favorite, fell behind quickly and never caught up. Kane finished second, only one minute behind Torres, followed soon by Manuel Salido, (Taraahumara) in third. Betah, and Zafiro were several miles behind when the first three finished. When Zafiro came into the stadium the two-mile relay was going on and for a half lap he sprinted and kept up with them bringing the crowd to a roar.

In the women’s event, Lola Cuzarare, age 18 and 90 pounds won again, finishing 29 miles in 5:37:45. She started in sandals but removed them for the last 25 miles because they were slowing her down.

After Kansas

In May 1927, a team of Hopis believed they were better than the Tarahumara and said that they would post $10,000 to race any distance against them. One of the Hopi had recently won the New York to Long Beach marathon in 2:47. Other native American runners wanted to get attention too. A “Chief Tail Feather” ran from Milwaukee to Chicago, 88 miles in 19:47 for $1,000.

Rodriguez announced that some Tarahumara were being trained to run in the “modern method” to enable them to complete in a six day race at Madison Square Garden in New York City. That never took place.

It was reported that the Olympic committee was considering including a special “Tarahumara” 100 km race for the 1928 Olympics at Amsterdam. As C.C. Pyle started to organize his 1928 transcontinental race, it was reported that a team of Tarahumara had agreed to enter, but they didn’t compete. The Tarahumara stayed home. They also declined to enter an 1928 International Indian Marathon held in Lawrence, Kansas, stating that they wanting instead to run longer ultra-distances.

Following a time trial run of 80 miles from Toluca to Mexico City and back, Mexico sent two Tarahumara, Jose Torres and Aurelio Terrazas, to the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics to run in the marathon. En route to Amsterdam, they visited New York City and said, “The streets are like our ravines — the sun never hitting the bottom.” The two were so used to running longer distances that after they crossed the finish line in 32nd and 35th, they kept on running, not realizing the race was over. Officials finally caught up with them to have them stop. They replied, “Too short, too short.” One of the runners many years later said the reason he lost was that the food didn’t agree with him.

After the 1920s

In 1930 ruins were discovered in the town of Babicora. They were believed to be part of an ancient great racetrack. News of the discovery was brought to Mexico City by a prominent American. The track existed at the base of a hill located in a sandy desolate plain. The hill is of circular construction, 600 feet high and about 300 feet wide which was believed to have served as a grandstand. The track consisted of four courses, each separated by walls.

In 1931 it was reported that the Tarahumara were in training to participate in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. They didn’t compete. In July 1943, it was announced that the Tarahumara participated in a 1,000-mile relay race to be held in Mexico in November. This again ignited American-wide interest in the tribe. Because of World War II, the event didn’t take place.

Runs to the Mexico-Texas border

In 1948 a Tarahumara 230-mile race was planned to run from Chihuahua, Mexico to El Paso, Texas, for the 14th annual Southwestern Sun Carnival. The race was organized by anthropologist Dr. Robert Mowry Zingg (1900-1957) of El Paso, who had lived with the Tarahumara for a year, becoming the world authority on the tribe.

After 45 hours, a 35-year-old Tarahumara, Pedro Paseno, brought a smoldering torch into El Paso. He ran across the International bridge from Juarez and handed the torch to El Paso mayor, Don Ponder, in the city’s plaza. The mayor then lighted an urn to signify the opening of the Sun Carnival. Paseno’s comment at the finish was, “My feet hurt.”

The other eight runners had dropped out by mile 87. “The Indians run with a peculiar rabbit-like hop, carrying forked poles for partial support. A thick, milky corn drink, carried in the escort car, provided their only food on the journey. When the tiny band halted for rest, its members stood leaning on their sticks.

In 1955 the Tarahumara ran a 10-hour relay bringing a torch to the border town of Juarez, to light a torch signifying 296th anniversary of the founding of the Juarez Mission in 1659.

Four years later, for the 300th anniversary, two 10-man teams of Tarahumara and Zapotecan Indians raced 1,700 miles to Juarez from Guelato, Oaxaca, Mexico. Runners ran in 15-minute stages as the others followed in a bus and station wagon. One runner was seriously injured when he fell from the station wagon. When the runners arrived in Juarez, they were welcomed by crowds and the blare of bands.

By 1960, Tarahumara runners had disappeared from public running competitions. They mostly struggled to live. Many articles were published over the years about their poverty, starvation, high infant mortality, and lack of education. Efforts were made by many to help.

A popular myth told, is that the Tarahumara ran the marathon in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games and that they did poorly, just as they did in the 1928 games. But these accounts tell the 1928 story as if it happened in 1968. Apparently Mexican officials tried to get the Tarahumara to run in 1968 but they declined.

How do they do it?

About 1975, Dr. Alexander Leaf (1920-2012) of Massachusetts General Hospital, who researched using diet and exercise to prevent heart disease, went to learn first-hand of the Tarahumara. He witnessed a women’s race of less than 100 miles. The children followed along rooting for their mothers. “But the youngsters could only keep up for about 10 miles.” He wanted to study their hearts, so he hauled in a stationary bicycle machine into the hills. But he couldn’t teach the Tarahumara how to pedal it. He tried taping their feet to the machine and it scared them away.

From his studies and examination of the Tarhumara, Dr. Dale Groom of the University of Oklahoma stated around 1977, “There is never any evidence of heart or respiratory distress and death from cardiac or circulartory complications is unknown.” He believed that genes were in important factor but genes alone could not account for the Tarahumara stamina. “Lifelong conditioning doubtless extends the capacity of the cardiovascular system in a phenomenal way.”

Running in America 1992-98

Rick Fisher, a Tucson, Arizona-based wilderness guide, and the Tarahumara’s promoter, brought several runners to the United States to compete in 1992 in races. They failed badly at Leadville 100, not understanding race procedures, and DNFed half way.

Ross Zimmerman and Gene Joseph co-administered the Tucson Trail Runners (TTR). After the Tarahumara’s poor performance in 1992, Fisher asked if the TTR would help train the Tarahumara runners as they prepared for 1993 races. Zimmerman ran a lot with them on trail runs and races near Tucson. Zimmerman found them to be “pretty normal guys, who told a lot of jokes. They are good-natured and smile easily. They are cautious and gentle, but also brave and tough.” Several Tarahumara men ran in the 1993 Tucson Marathon and several Tarahumara women ran in the half marathon. Zimmerman paced one of the runners during 1993 Leadville 100 and the Tarahumara were successful and won that year.

Fisher was highly critical of the American ultrarunning community and its race directors for what he thought was poor treatment toward the Tarahumara. Fisher offended many in the community and claimed that many ultrarunners offended the Tarahumara. Nevertheless, Fisher deserves great credit for giving Tarahumara the opportunity to run with some amazing athletes in a different culture.

From 1992-98, about 35 Tarahumara entered eight ultras in America. Most of them finished in the top ten and there were four outright wins with two course records. In addition to the 100-milers at Leadville and Wasatch, they ran at 1995 Western States 100 and 1997 Angeles Crest 100.

A lasting legacy

But perhaps the Tarahumara left their greatest impact in the 1920s when they first demonstrated their running abilities to the world. Dr. Mark Dyreson, a Professor of Kinesiology and History at Penn State University, wrote this summary about the Tarahumara contribution in the 1920s in his article “The Foot Runners Conquer Mexico and Texas,” “The Tarahumaras signified the potential for amazing prowess that modern folk hoped was still alive somewhere in the human species. During the 1920s the foot racers played a crucial role in the growing global fascination with endurance records. The connection between modern roads and ancient running traditions was significant. A half a century later, legends about the Tarahumaras served as one source of inspiration for the emergence of ultradistance races through the landscapes of the American Southwest.”

Sources

- Mark Dyreson, “The Foot Runners Conquer Mexico and Texas”

- Andy Milroy, North American Ultrarunning: A History

- “The Longest Race in the World”

- When the Tarahumara Indians Ran

- Tarahumara Racing Team Copper Canyon

- Ross Zimmerman, “Born to Run; Slices of Truth and Piles of Salt”

- Sioux City Journal (Iowa), Mar 16, 1867

- Los Angeles Times, Feb 11, 1894, Mar 22, 1908, Aug 8, 1923, Jan 23, 1927, May 25, 1927, Jun 15, 1930

- The Indianapolis News, June 29, 1889, Sep 1, 1906

- The Boston Globe, Nov 8, 1908, Feb 28, 1914, Nov 10, 1926, Dec 29 1948

- Norwich Bulletin (Connecticut), Jan 28, 1916

- The Allentown Leader (Pennsylvania), Oct 27 1917

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Sep 10, 1920

- El Paso Herald, Nov 8,9, 1926, Oct 18, 1954, Mar 21, 1959

- The Daily Oklahoma, Nov 9, 1926

- The Indianapolis Star, Feb 12, 1927

- The Austin American-Statesman, Feb 6, 27, Mar 3, 13, 16, 19-20, 22-23 24-30, Jun 15, 1927

- The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), Mar 3, 1927

- Victoria Advocate (Texas), Feb 7, 1927

- The Herald-News (Passaic, New Jersey), Jan 7, 1927

- Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, NY), Feb 10, 1927

- San Antonio Light (Texas), Mar 23-26, 1927

- The Galveston Daily News (Texas), Mar 13, 1927

- El Paso Times (Texas), Mar 14, 15, 19, 23, 1927, Dec 28-29, 1948, Dec 5, 1955, Jul 7, 1974

- Iola Daily Register and Evening News (Kansas), Apr 22-23, 1927

- The Manhattan Mercury (Kansas), Apr 28, 1927

- Dayton Herald, May 20, 1927

- The Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois), Jun 3, 1927

- Detroit Free Press, Apr 20, 1928

- Albuquerque Journal (New Mexico), Dec 29, 1948

- Nevada State Journal (Reno), Aug 25, 1968

- Lubbock Avalance-Journal (Texas), Apr 19, 1977

- The Daily News-Journal (Murfreesboro, Tennesee), May 15, 1977

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), Mar 20, 1992, Jan 9, 1995