Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 32:42 — 37.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

For centuries, many Native Americans were known to be outstanding long-distance runners who could run ultra-distances. Their talents were used in important roles to carry messages and news to distant communities. One of the most famous ultra-messaging events took place in 1680 when a very coordinated system of message runners were dispatched from Taos Pueblo, in present-day New Mexico to Hopi Villages in present-day Arizona, nearly 400 miles away, to coordinate a successful, simultaneous, revolt involving 70 villages against their Spanish oppressors.

In the 1860s a Mesquakie runner in his mid-50s ran 400 miles from Green Bay, Wisconsin to the Missouri River to warn another tribe about an impending attack. Such runners would dedicate their lives to this role of being an ultrarunning messenger.

As Native American Talents became more widely known by Anglo-Americas, competitive wagers arose to prove their capabilities. In 1876 “Big Hawk Chief” ran 120 miles within 20 hours accompanied by an observer on a horse. In the early 1900s gifted ultra-distance runners were known to be among the Hopi, Yaqui, Tarahumara in Mexico, and the Seri of Tiburon Island in the gulf of California. The Hopi had been known to cover 130 miles within 24 hours.

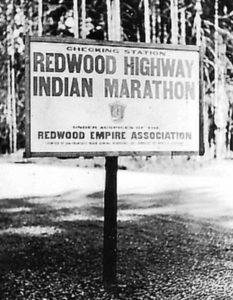

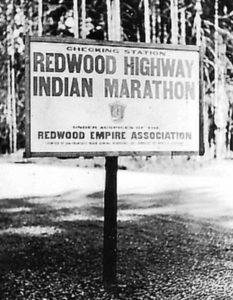

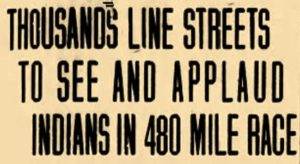

The Native American runners occupied a central role in ultrarunning during the early twentieth century. Sadly, this fact has largely been forgotten or overlooked. In 1927, a 480-mile race took place on the California/Oregon Redwood Highway that received intense daily attention in newspapers across America. This article will provide the detailed story for the first time of that historic, forgotten race.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. This book, with more than 400 photos, tells a 130-year story of many of the early crossers in their own words. It also covers the creation of the trails, bridges, Phantom Ranch, and the water pipeline, the things that are seen during a rim-to-rim journey. |

Plans for the 1927 Redwood Indian Marathon

By 1921, the running talents of the Native Americans were being noticed. The Los Angeles Herald, suggested, “If the Olympic commissioners want to find an Olympic Marathon runner who can beat the world, it might be a good scheme to look the Indian reservations over.” By 1926 In Arizona, “Indian Marathons” started to become features at local fairs and festivals. One such race was organized in Phoenix, running 25 miles from downtown to the fair grounds. “Only Indians who, in former days, ran over hot desert sands for various tribal missions will be called upon to appear in the race. The Hopi and Navajo Indian runners will serve as one of the best advertising features of the affair.” Soon this idea spread, to link exhibitions of Native American extreme running with national events.

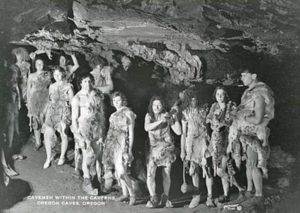

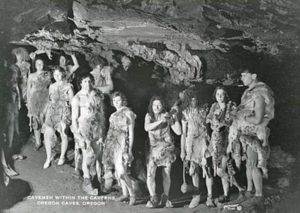

In March, Clyde Edmunson, the manager of the Redwood Empire Association, announced that a 480-mile race would be held in June and that a dozen Indian tribes had agreed to enter runners for prizes of $2500. (This was a stretch, because no tribes had actually committed.) In Oregon, The “Caveman Association” of Grants Pass, a club of civic boosters, also jointly sponsored the idea and they claimed that the event would be “the longest race of its kind in history.”

Harry Lutgens (1892-1968), the owner and editor of the San Rafael Independent was named the general chairman of the event. He went to work organizing and promoting the “Redwood Indian Marathon.”

By mid-April, some potential entrants from California started to express interest but they didn’t pan out. Counties were “scouring the hills for husky braves to make the race.” At first the event was limited to runners from California or Oregon, but they were having trouble getting enough interest, so they soon opened up entry to any Native American “provided they are sponsored or backed by an official organization or responsible individual who will attend to their preliminary training, take them to San Francisco and see that they have a trailer car to take care of them at stops during the race.” The runner also needed to be from an Indian tribe and at least one-quarter Indian.

Without the Internet for live online results, Lutgens called for the revival of the old Indian method of communication, smoke signals. “As the race progresses, the positions of the various contestants will be announced by signal fires strung out along the entire route of the race.” That turned out to just be a marketing attention-grabber. A newspaper on the route wrote that the race would “prove to the paleface world that the Indian is not a dying race, but a strong and virile one.”

Prizes were set to $1000 for 1st place, $500 or 2nd, $300 for 3rd, $200 for 4th, and five prizes of $100 each for the next five finishers that reached the finish within 24 hours of 4th place. Several communities along the way also promised to put money into the pot, awarding those who first reached their various towns.

June 14, 1927, Flag Day, was chosen for the start of the race. Entry forms were sent out on May 17th.

The Karuk

Oregon promoters hoped to find runners to beat those in California. The Grants Pass Chamber of Commerce sought to find nearby Karuk tribe runners from the town of Happy Camp, which was located 70 miles away in northern California on the Klamath River.

Happy Camp was a rural community of miners, farmers, hunters, trappers, and was populated with many Karuk Indians. Herbert G. Boorse (1873-1932), the owner of the Happy Camp General Store, was named to train the Karuk runners and be a sponsor of the race. Boorse gave the runners Indian-like names which he knew would be liked by the public and enhance his sponsorship of the race.

They later moved their training to the city park at Grants Pass to get used to running on pavement. John R. Harvey (1865-1943), the manager of Grants Pass chamber of commerce said, “Our runners are getting in fine shape and they are going strong. These Karuk boys are in the marathon to win. The Karuk Indians are noted for their endurance and they boast that they are the only tribe able to run down the bear and the elk”

As can be expected for 1927, newspapers mentioning the event resorted to the racial terms of the time. “Red men, including trappers and hunters as well as tribesmen who have left reservation or family lodge to enter sports events promoted by the white man, are being signed up for the start.”

The Zuni

Race preparations

The highway in those days was mostly a narrow two-lane unpaved road winding through forests and redwoods. It was promoted as “A road more typical of California than any other route within its borders, a highway that breathes the very spirit of the West in the wide spaces of its vision and in the wilderness of beauty which it opens to the motorist.”

The marketing strategy was to connect “wilderness” and “spirit of the west” with America’s recent fascination with Native American runners. “Like a flash-back to the days when red braves sped overland afoot with messages from tribe to tribe will be the scene presented by these genuine tribesmen pressing on almost continuously for from ten to fifteen days to reach their goal.”

While the race would start at the San Francisco, with no bridges across the bay, they would first run to the ferry as a group and then be taken across to Sausalito where the true race would begin to the north through the Marin Hills.

Runners arrive

Lunches and dinners were held for the runners and their teams. The eight Karuks were accompanied by the Oregon Cavemen club. “The Cavemen were more terrifying than the Indians, being clad in coyote skins and ‘armed’ with stone-age clubs.”

A caravan of cars were obtained for race officials, the press, and some “moving picture outfits” who would film the event. Each runner would be followed by an automobile containing his backers, trainers, and an inspector.

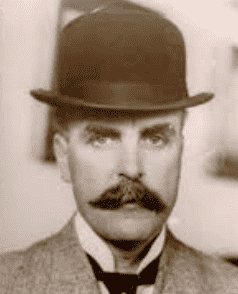

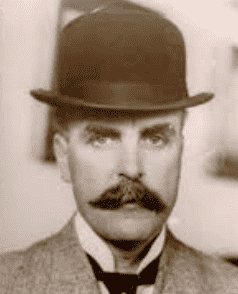

The person to fire the starting gun was an odd choice. He was Al Jennings (1863-1961), a former bank bandit and train robber from Texas and Missouri, but at that time was the mayor of Crescent City, California, along the Redwood Highway. Jennings was making silent movies and writing novels. In 1899 he had been sentenced to life in prison but was pardoned in 1904 by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Race Roster

Eight Karuk runners were entered along three Zuni runners. Each runner competed “under the colors” of a Redwood Empire county, town, or club, and also sponsored by local businesses.

The Karuk runners

The Karuk entrants were represented by the Oregon Cavemen, the booster organization in Grants Pass. The newspapers always referred to these runners by their Indian-like name that had recently been given to them by their trainer, Boorse.

Here are Karuk runners with their bib numbers: Rushing Water (1), Flying Cloud (2), Fighting Stag (3), Falcon (4), Mad Bull (5), Thunder Cloud (6), Sweek Eagle (7), and Big White Deer (8).

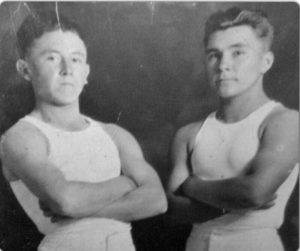

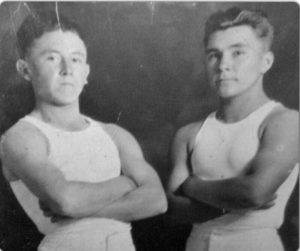

Their real names were known. Three were brothers, Mad Bull, Fighting Stag, and Rushing Water, from the Southard family. They all were, John Wesley Southard (Mad Bull) age 23, Marion Southard (Fighting Stag), age 20, Gorham Lincoln Southard (Rushing Water), age 18, David Henry Huey (Falcon), age 29, referred to as the chief of the group, Henry Thomas (Flying Cloud), age 19, W. E. Simpson, Elder Earl Barney, age 19, and James D. McNeil.

The Zuni runners

The Zuni entrants were from Manuelito New Mexico. Here are the Zuni runners along with their bib numbers, Jamon (9), age 32, Melika (10), age 55, and Chochee(11), age 48. All had been trained for endurance since their childhood and all had won awards in inter-tribal Indian races of New Mexico.

Each of the Zuni runners competed “under the colors” of a Redwood Empire town or county, sponsored by local businesses. Jamon ran for “Marvelous Marin” County, Melika for the town of Willits, and Chochee for Humboldt County. None of them had ever been to those places before.

The Start, June 14

June 14, 1927 was race day. The eleven runners assembled at San Francisco City Hall along with about 5,000 cheering spectators. Major James Rolph Jr. (1869-1934) of San Francisco was introduced to the runners and he handed each of them a letter of introduction to be presented to Mayor George J. Fox (1864-1837) of Grants Pass, Oregon, on their arrival. The press were in a frenzy. One photographer punched a rival photographer in the nose as they tried to get a prized photo.

The runners sprinted fast toward the ferry and were amazed that they stopped the numerous street cars just for them. “They all wore heavy running shoes, running pants, and some wore belts with their names on them.”

It didn’t take them long to reach the Ferry Building, just 15 minutes. They were then brought by automobiles to the Golden Gate ferry.

All the runners stayed together for the first five miles jogging slowly. But then Jamon, one of the Zuni, suddenly sprinted into the lead like a shot. He ran fourteen miles in just 1:19. Soon he was leading the field by nearly a mile. However, his fast start overcame him. He stopped for a rubdown rest while Rushing Water and Flying Cloud started to catch up.

During the early afternoon, Jamon reached San Rafael (mile 14) and won $100 for being the first to arrive in that city. That was the reason for his fast initial sprint. He then waited for the other two Zuni to catch up and they all rested at San Rafael for two hours. Jamon was injured there when a movie camera tripod jabbed him in the back. Flying Cloud of the Karuk went into the lead.

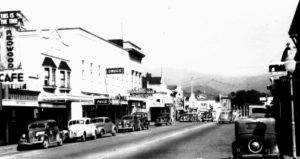

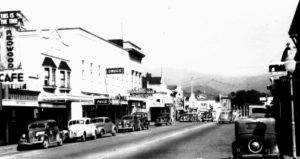

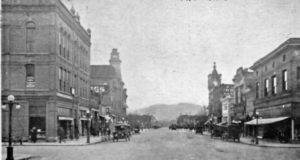

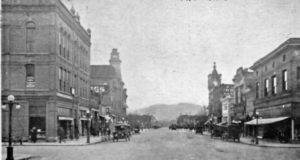

Petaluma

Still on day one, at 5:53 p.m., after six hours of running, Flying Cloud was the first to reach Petaluma (mile 38), a small city of about 8,000 people. The city was known for its chickens was called the “Egg Capital of the World.” As Flying Cloud approached, the fire department set off sirens to let the city know the first runner was arriving. Crowds came out and lined Main Street, cheering Flying Cloud as he went by. Many people climbed up on house roofs to get a good glimpse.

A throng of well-wishers followed after Flying Cloud. “The excitement knew no bounds and he was followed to the checking place, later given attention, and continued after a 32-minute stop.” A long line of cars followed him north, heading out of town along with many pedestrians. But soon his trainer following him in a Buick, decided that it was time for him to have a good supper and turned him around back to Hotel Petaluma for about an hour. In 46 minutes, Rushing Water, was the next runner to arrive.

A banquet was held at the Occidental Hotel in honor of the 20 Oregon Cavemen who arrived clad in wildcat and coyote hides. The cavemen gave talks at every stop to talk about the wonders of southern Oregon. Herbert Slater (1873-1847), blind state senator and newspaperman was the toastmaster of the event. Carrier pigeons were released with messages for the San Francisco mayor.

After sunset, the motion picture men wanted to still film as the final runners arrived into town. “Fat” Bill La Rue (1888-1932), a well-known heavy-weight boxing contender was helping the movie delegation put out flares for light, and his overcoat caught on fire. “He was mightily scared but said, ‘It’s alright as long as the fire department was not disturbed.’”

The three Zuni were the last to arrive at 9:22 p.m. “The group presented a pretty picture as they jogged along Main Street and all along the line they were heartily cheered, despite the fact that they were the last to reach this city.” They were presented baskets of eggs that were made by high school girls.

Large crowds in automobiles followed them as they continued north toward Santa Rosa. The traffic was incredible. Officer Andrew Stein (1887-1970) was in charge of traffic on Main Street. “The crowd in front of the Courier office, the official checking station, was so large that it was impossible for machines to make their way along the thoroughfare.” Some of them were moving so slowly that they were “steaming like clam bakes.” After midnight the officer had to get the constable to help him because it was still so busy.

Thunder Cloud and Big White Deer had to stay the night at Petaluma because of cramps and exhaustion. They both tried to continue on at 4:45 a.m. the next morning but Thunder Cloud didn’t make it far and dropped out of the race with an infected foot.

Flying Cloud extended his lead and was the first to reach Santa Rosa (mile 54) with an eight mile lead over Rushing Water. At 3 a.m. he reached Healdsburg (mile 69), a small town of about 2,000 people, where he checked into a room to sleep.

An accident occurred during the first night along the race route. “Victor Grande of Santa Rosa, who was motoring south encountered a group of runners on the highway, swerved his car, and ran into a ditch. He suffered a broken collarbone and right arm and was taken to a hospital for treatment.”

Day 2, June 15

At 7:30 a.m. after sleeping about four hours, Flying Cloud left Healdsburg about four miles ahead of Rushing Water who had run more through the night, cutting four miles into Flying Cloud’s lead. When Rushing Water arrived at Healdsburg, he was expecting to find Healdsburg’s famous prunes on his breakfast table. Prunes were the most important industry in that town during that time. Rushing Water asked, “Where are the prunes? I thought you raised lots of ‘em here!” He was quickly give a large supply of them and left at 9:45 a.m.

Geyserville (mile 76) was the gateway to “The Geysers,” the world’s largest geothermal field. At this tiny town ahead, some young men pulled a prank on their town. Bruno Solari (1911-1983), age 15, “dressed in the proper running togs and grease paint applied. He looked just like a redskin. Solari jogged through Geyserville and was checked in at marathon headquarters. The crowd cheered, horns tooted.” He continued on running through a wildly enthusiastic crowd. But as he continued on, since he wasn’t in running shape, he soon became exhausted and was forced to stop. Then someone recognized him and the gig was up.

When the true leader, Flying Cloud arrived at Geyserville at 9:41 a.m., the enthusiasm had diminished. There were quite a few scowls as the spectators took a close look to see if he was fake or genuine. Rushing Water was only 1.5 miles behind.

Far behind, the three Zunis were bringing up the rear after spending the night at Santa Rosa. At Windsor (mile 62), Jamon, stopped and was taken back to Santa Rosa for a hot bath and treatment of his blistered feet. It was feared that he would have to drop out of the race there, but later he would continue on alone.

Further up the road in the lead, Flying Cloud arrived at Cloverdale (mile 86). It was a small town of 800 people, and home of many Pomo Indians. He came into town at 12:44 p.m. and stopped to avoid running during the hot day. Mad Bull and Falcon caught up during the afternoon and also stopped to sleep. At 8 p.m. the three left Coverdale together, feeling much refreshed. Within a mile Mad Bull took the lead. It was believed that Flying Cloud disliked the quiet-natured Mad Bull and that a charged rivalry had developed between them. Mad Bull later said, “I was resting when back down the road I saw Cloud come into view. I changed my shoes and took off. He never caught me.”

The hills between Coverdale and Hopland really bothered the runners but Mad Bull and Flying Cloud were moving well. The two Zunis, Melika and Chochee, also seemed to be gaining strength and speed and were catching up.

Mad Bull’s lead increased by two miles as he passed through Hopland (mile 103) and its massive hop fields. Injured Big White Deer was about five hours behind. He was no longer running, just walking, but also gaining. Jamon, was slowly pulling up the rear and arrived at Cloverdale later during the night. It was reported, “All runners are showing signs of suffering from the heat and few if any have escaped blisters from running on the hot pavement. Carbon monoxide fumes from automobiles that crowd too close to the runners are also telling on them.”

Mad Bull

Day 3, June 16

By the third day, the tasks of continuing to grind out miles and struggling with poor sleep patterns were taking a toll on all the runners. Mad Bull arrived in Ukiah (mile 118), a city of 3,000 people at about 6:00 a.m. with about a three-mile lead over Flying Cloud who took a long stop there letting him stretch his lead to about eight miles by noon. The two Zunis were an additional seven miles behind. The town of Ukiah also grew hops. Prohibition had affected the area but hops were now exported to other countries, especially to Germany.

At Willits (mile 143), a town of 1,400 people, Mad Bull arrived first at 12:55 p.m. and won a Ford automobile and cash. In order to claim the prize he needed to finish the race. During the past 25 hours he had covered an impressive 60 miles. He stopped to sleep, letting Flying Cloud catch up at 4:10 p.m. But Flying Cloud also stopped for a rest. Mad Bull hit the road again around 6 p.m. and shortly after, the two Zunis, Melika and Chochee, also showed up at Willits. They planned to sleep there until midnight.

As for the others, the long trek was wearing them down. Sweek Eagle, Rushing Water and Falcon were together more than 20 miles behind. Rushing Water and Falcon were in bad shape and were taken to receive medical attention but later returned to their stopping point to continue. A doctor shuttled up and down the road in a car, ready to care for any runner who got sick or injured. Fighting Stag was “in distress” back at Ukiah. Big White Deer was about 30 miles back. Bringing up the rear, Jamon, about 72 miles behind the leaders but still determined to catch up to his fellow Zunis.

Jack McDonald (1899-1997) was a sportswriter for at the San Francisco Call-Bulletin newspaper. He was the only reporter to travel the entire way with the race. At Ukiah during the night, the Western Union office was closed. He wanted to get out an article about the race’s progress. “He jimmied the door of the telegraph office and sent his own story. McDonald was a radio operator in World War I. His wire gave the operator in San Francisco a scare when he heard the Ukiah call letters coming over at midnight.”

After just three days, the organizers of the Redwood Indian Marathon were thrilled by its initial attention and success. They announced that the event would be an annual contest, open to all Indians and aborigines from all over the world. They hoped to attract runners from Bolivia, the islands of the south Pacific, and even Africa.

Day 4, June 17

In the morning at 8 a.m., Mad Bull arrived at Cummings (mile 173), a small stopping point on Rattlesnake Creek after covering 37 miles during the night. He had stretched his lead to 14 miles ahead of the rest of the field. He stopped there for a short rest. The runner, Jamon was 110 miles behind still suffering from bad blisters but continued on in the morning as he waved farewell to a small crowd.

Harry Ridgeway was the president of the Marvelous Marin club and referee for the race. He drove his LaSalle sedan up and down the road from leader to the last runner. Sometimes he drove more than 300 miles in a day to make sure the competitors were running all the way. The road was always well covered by cars and he later reported that there was never a charge of cheating.

At noon, Mad Bull reached Coolidge and quickly sent on, going strong, determined to put greater distance between himself and the two Zunis who he heard were moving well. Melika was 14 miles behind and Cochee was a few more miles in the rear. They both were very anxious to overtake Mad Bull. “They refused to hold back, defying their trainer and threatening to scalp him. During an argument they broke away and started off against his orders and planned to run to suit themselves as they rebelled against the restraint.” The day went very well for these determined runners and they cut into Mad Bull’s lead. He would stop every four hours to change into fresh socks and dry running shoes.

Sweek Eagle, who was about 20 miles behind the leader, was believed to be a dark horse for the win because he just kept plodding along at a steady pace without taking long rests. He appeared to be in fine condition. He was the tallest of the runners at 5’11”, 160 pounds and had an impressive long stride.

In the evening, Mad Bull arrived at Garberville (mile 219) at 7:40 p.m. still holding a 12-mile lead. He checked into Hotel Benbow, a new spacious resort inn that would soon become a popular destination for motorists on the Redwood Highway, including the Hollywood elite. He soaked in a hot bath, had a meal and slept in one of the hotel’s best suites for several hours.

Day 5, June 18

On the fifth day, Mad Bull passed through Dyerville (mile 243), a small crossroads town, before noon, marking the halfway point of the race. (This town would be completely destroyed in 1955 from the Eel River.) His lead had dwindled to nine miles over Melika and Chochee was just an additional two miles further back. They were no longer running, and instead trying to use a walk-only strategy that seemed to be working. The Zunis said that they could start running again if Mad Bull’s feet started to blister.

The standings at this point with mileage were: Mad Bull, 243; Melika, 234; Chochee 232, Flying Cloud, 214; Falcon, 214, Rushing Water, 207; Fighting Stag, 207; Big White Deer, 188; Sweek Eagle, 181 and cramping; Jamon, 101 was being transported in an automobile to get medical attention again but still was not out of the race, knowing that he had 15 days to finish.

In the afternoon, Chochee, at Pepperwood (mile 263), ten miles behind Mad Bull, became quite ill and was stopped by his trainer until the doctor could examine him. He had been pushing for 15 hours straight, covering 50 miles, trying to overtake Mad Bull, but he would now fall way behind. Mad Bull was ahead at Scotia, a lumber town. He was smiling and looking fresh. Melika had fallen back to 21 miles behind.

Mad Bull reached Fortuna (mile 276), at town of 1,200 people on the Eel River, at 5:30 p.m. The town was known for its vegetable crops, berries and fruits, and for the fresh fish from the river. But the lumber industry had really taken over. Girls at Fortuna tried to flirt with Mad Bull because “they wanted to bug him,” but he stuck to the business at hand. His stop was short, and then he ran strong for the five miles to Loleta in 75 minutes. He had arrived at the coast where the Eel River flowed into the Pacific Ocean.

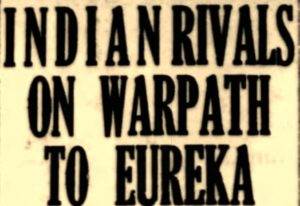

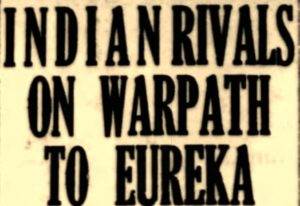

Mad Bull arrived at Eureka (mile 298), a large city of 16,000 people, at 11 p.m. with about a 30-mile lead ahead of the next runners, Flying Cloud and Falcon. A crowd of about 500 fans stayed up to cheer him to the noise of fire sirens. He announced plans to stay for the night. He took a warm bath and fell asleep in the tub.

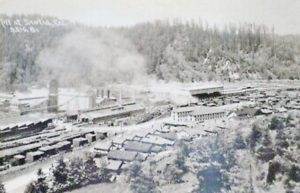

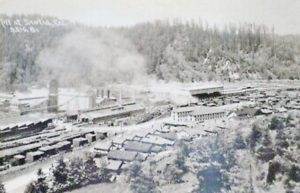

Eureka was a transportation connection to the “outside” world. Lumber and goods were shipped through there on train, by ship, and now by the Redwood Highway. It would soon experience a population It was nicknamed “Queen City of the Ultimate West” but it also was the home of earthquakes.

“Leslie Buck (1902-1999) age 25, was nominated for the job of posing as Mad Bull and the rest of the guys painted him up, put him in shorts and tennis shoes and he was ready to run. Lee Lungren’s car was signed with Mad Bull’s number, and accompanying him in the car was Harry Wyatt (1896-1971) as “trainer.” Around 11:30 p.m. the fire whistles blew and people got out of bed and headed for the plaza, including Les Buck’s father, Chris Buck, who was a runners’ fan.”

“Around midnight here came Les, followed by his car and trainers complete with a local night watchman who moved the crowd back. They fooled everyone, passing within three feet from his dad who failed to recognize him. The only time Les was scared was when officials ran out of the Hotel Arcata and attempted to get the running party to stop to come in and register. Les ran almost to the old Grammar School and then jumped in a car and headed to get into his street clothes.”

Way back, at mile 86, Jamon, the determined Zuni, finally was withdrawn from the race by his trainer, Mike Kirk. His feet were in too much pain to continue. Nine runners remained. Flying Cloud and Melika teamed up in second place and were enjoying each others’ company. Flying Cloud could not speak the Zuni language and Melika could not speak English. Flying Cloud said that they could make plenty of signs to communicate. It was reported, “The two apparently were quite chummy. At one point Flying Cloud was given an orange by one of his handlers. He stopped to eat it and Melika refused to go on without him.” Flying Cloud was suffering from a sore knee. Falcon had fallen behind ten miles further back in fourth place.

Day 6, June 19

After a nice 8.5-hour sleep at Eureka, Mad Bull left at 7:30 a.m. It had been his longest rest during the race. As he progressed up the road, his support crew would often hand him a glass of orange juice containing two raw eggs for fuel. Other times when his crew was away he drank water from numerous springs along the road.

At 8:30 a.m. he arrived at Arcata where the imposter passed through the night before. The story continued, “The fire whistles blew and the real Mad Bull came through. There was almost a riot on the plaza as one bunch said he came through in the night and the other said there he is right now. The argument continued for months, was it midnight or 8:30 in the morning.”

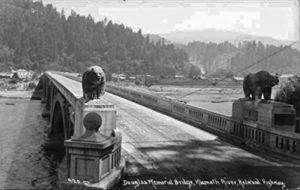

Mad Bull crossed the Klamath River (mile 359) on the new Douglas Memorial Bridge at 12:12 a.m. (The bridge would be destroyed in 1964 due to a terrible flood.) Flying Cloud crossed the bridge only 90 minutes later and then rested for an hour.

Mad Bull’s strategy to stay ahead was to never run up the hills. He would power walk them and run the downhills and flats. He still held a 14-mile lead over Flying Cloud who had gone ahead of Melika. Flying Cloud celebrated his 20th birthday that day by running. Melika finally abandoned the idea of only walking, and ran strongly into Eureka at 3:20 p.m. where he rested for an hour.

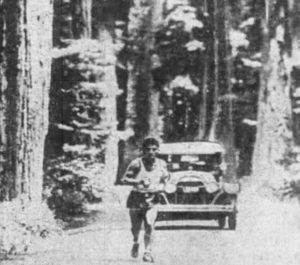

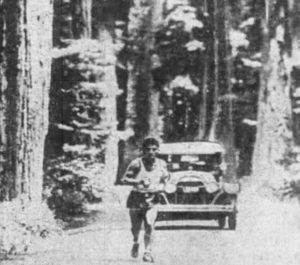

With the highway skirting the Pacific ocean for nearly 100 miles since Eureka, it was reported that Mad Bull “was greatly refreshed by the invigorating air from the sea. It was in this region that many of the Karuk ancestors hunted, fished and fought.”

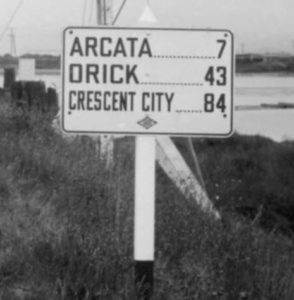

During the night Mad Bull passed through Trinidad in the afternoon and Orick (mile 333) at 10 p.m. An observer at Orick wrote, “The long sleep which he enjoyed last night, his appearance as he reached here and the big lead he now possesses, with but one-quarter of the distance yet to be covered, seem to make him the overwhelming favorite to win.” Mad Bull continued on and stretched his lead to 20 miles during the night.

Day 7, June 20

With the end getting closer, Mad Bull continued to pile up the miles determined to hold his lead. On day seven, he reached Requa (mile 362) near the mouth of the Klamath River at 11:40 a.m. holding a 15-mile lead ahead of charging Flying Cloud. Melika was five miles further back in third place. It was thought that the winner would be one of these three. The pace had been pretty fierce. Since the previous day, Mad Bull had run 62 miles, Flying Cloud 70 miles, and Melika 66 miles.

“Mad Bull was approximately 70 miles from the Oregon State line and seemed to sense the goal as a horse would his stall after a hard drive. He grinned cheerfully as he loped along the highway 1,000 feet above the misty Pacific waters. He had left the Redwood forests and was high on the picturesque bluff.”

Chochee, the ill Zuni, had struggled to make it to Eureka during the morning and suffered from a sprained ankle. “Though he expected to continue the run, observers contended that the odds were too great against him to enable him to help Melika gain any ground.”

Next, Mad Bull arrived at the coastal town of Crescent City (mile 385), just 20 miles from the Oregon border, at 5:17 p.m. He was 14 miles ahead of Flying Cloud and had 87 miles to go to reach the finish at Grants Pass, He rested at Crescent City until 10 p.m. when he heard Flying Cloud had caught up. Flying Cloud had arrived at 9:19 p.m. Mad Bull’s 20-mile lead from the previous day had evaporated. But Flying Cloud needed rest and stayed for three hours, taking up the chase again a little after midnight, nine miles behind the desperate Mad Bull.

A report from the road included, “Flying Cloud in good condition and running at a steady pace. These same tidings have Mad Bull suffering from the effects of the great efforts which carried him into the lead and at one time put him 30 miles out front. It appears that a real contest looms between these two before the finish line.”

Chochee, with the sprained ankle, had re-entered the race near Eureka. Sweek Eagle who had also been temporarily out because of injury also resumed running close behind Chochee. They were about 100 miles behind. Chochee eventually withdrew from the race at Loleta, at mile 280.

Day 8, June 21

By dawn on the eighth day, the racing was intense. Mad Bull reached Patricks Creek (mile 412) at 5:05 a.m. determined to reach the finish at Grants Pass by evening. Flying Cloud also arrived there at 8:45 a.m., losing ground on Mad Bull. Melika was more than 30 miles behind and had left Crescent City at 7:10 a.m. that morning. “All three leaders were walking today, the pace having begun to tell on them. Flying Cloud was slightly ill, but was exhibiting a fighting spirit and was determined to finish second at least.”

At about 11 a.m., Mad Bull crossed into Oregon with about 44 miles to go. His pace was continuous as he rested only a short time during the day. At the one-week mark from the start at Sausalito, he had run about 440 miles over those seven days. At 8:15 p.m. he was within twelve miles from the finish and he started running again. Feeling the urgency of finishing, he only stopped for several minutes once, eight miles from the finish, for a cup of coffee and then ran on.

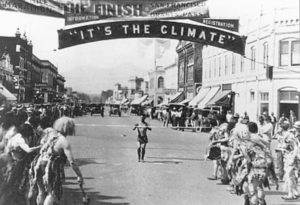

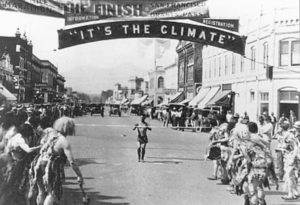

Finish

Four miles from Grants Pass, about 100 automobiles followed Mad Bulls progress toward the city. Near midnight on June 22, 1927, Mad Bull ran through a lane of automobiles parked on the Grants Pass streets that were filled with people who wanted to see the finish of the race. It was estimated that even at the late hour, there were 4,000 people in the streets. “Men, women and children tried to outdo each other in noise-making, whistles screeched, klaxons sounded and wild confusion prevailed.” It was “a scene such as this city has not seen since the signing of the armistice, ending the world war.”

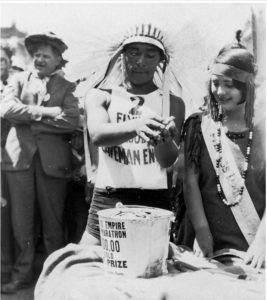

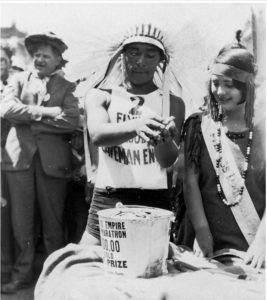

At 12:16 a.m. Mad Bull finished the Redwood Indian Marathon to win the $1,000 prize, plus town prizes. He finished ten miles ahead of Flying Cloud and about 30 miles ahead of Melika. His finish time for the 480 miles was 7 days, 12 hours, and 34 minutes. It was reported, “Mad Bull came in smiling but worn out.”

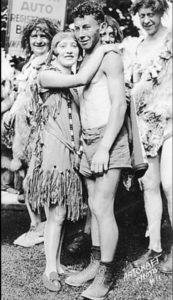

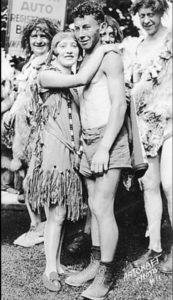

“Just as he crossed the finish line, Miss Redwood Empire, ‘Little Fawn’ of the Hopi Indians rushed out, threw her arms around the winner and gave him a tribal kiss.” Movie men focused their cameras on him and he forced a smile but said nothing other than “thank you.” The Karuk put on a demonstration of a tribal dance in celebration.

Flying Cloud finished in second place about eight hours later, at 8:40 a.m., “lame but game.” He had finished strong, clocking 12-minute miles, and won $500. “As he crossed the line marking the goal, he sank on the running board of a nearby car, but still had plenty of spirit to smile at the request of the cameramen. As soon as the movie men were through, the weary runner was whisked away to bed.”

Mad Bull slept late into the morning despite efforts to rouse him to reenact his finish for daytime pictures and the movies. He was finally up by noon to receive his total of $1,325 prize money. Two hours later he was the proud owner of a new Chrysler automobile with his name, “Mad Bull” painted on the side. The car cost him $1,050 cash. Flying Cloud also bought a car with his winnings. Mad Bull took his mother and “Little Fawn” for a ride up and down Main Street of Grants Pass. Reflecting on his run, he said, “I would run until I thought I was giving out, then I’d get a second wind and keep going. A couple of times I go so tired I thought I’d have to quit.” Thinking about the future, he said that maybe he would settle down and get married.

That evening a banquet was given for the three top finishers. Melika, age 55, was “given an ovation and his face, usually stolid, occasionally broke into a smile.” Mad Bull’s brother, Fighting Stag finished the next morning at 8:52 a.m. running strongly.

Final Results

- Mad Bull, 7 days, 12 hours, 34 minutes

- Flying Cloud, 7 days, 21 hours, 18 minutes

- Melika, 8 days, 2 hours, 49 minutes

- Fighting Stag, 8 days, 21 hours, 10 minutes

- Sweek Eagle, finished, time unknown, more than 9 days

- Falcon, finished, time unknown, more than 9 days

- Big White Deer, finished, time unknown, more than 9 days

Did Not Finish

- Rushing Water, mile 341

- Chochee, mile 280

- Jamon, mile 86

- Thunder Cloud, mile 38

After the race

With all the press coverage across America, Mad Bull became an instant celebrity. “Mad Bull, unknown outside the confines of his own stamping ground, is now a Pacific Coast celebrity as the result of seven consecutive days of publicity.” In the days following the race, the runners stayed in California and were guests at events such as a huge July 4th parade in Eureka where Mad Bull drove his new car.

It wasn’t surprising that other runners wanted find a way to get the spotlight also shown on themselves. A George W. Hooley of Newark, New Jersey claiming to a champion professional long distance runner, issued a challenge to run a 500 or 1,000 mile races against Mad Bull.

Efforts were made to try to put into place a Man vs. Horse race involving horse riders racing against three of the Karuk who had run in the Redwood Marathon. It was believed that they could beat the horses in a 70-mile race. It never took place.

In September, Mad Bull was working as a hop picker and participated in a hop picking contest at Santa Rosa in the Gus Peterson hop yards. He came away as the champion after picking 616 pounds of hops. Flying Cloud was also working as a hop picker in the area.

A promoter arranged a vaudeville tour for the runners and they appeared throughout Northern California. But the tour fizzled due to poor organization by the promoter. Mad Bull returned to Grants Pass and worked at whatever jobs he could find. For a time, he was a flagman for a crew improving the Redwood Highway.

As for the Zunis, they took the train to Los Angeles where Jamon was to being training for a 500-mile Los Angeles to Phoenix Marathon. “His older companions have had enough of it and will not try again but will leave Los Angeles for their home.” It does not appear that the 500-mile race took place.

The later years

The 1927 race was so successful in attracting attention that it was held again in 1928. There were 29 runners entered. Mad Bull, Flying Cloud and Melika again ran and this time Flying Cloud won in just less than seven days, crushing Mad Bull’s previous time. Melika placed second. Mad Bull didn’t finish because he claimed that someone sabotaged his race by dumping some glass shards in his runner shorts. He later chafed badly and had to pull out. An uninvited white runner ran the race “bandit” by someone trying to prove the white man was better than the Indian. The runner only made it to Healdsburg (mile 69) when he lost interest and quit.

A third race was being planned for 1929, but it never came together. Later with the stock market crash and onset of the Great Depression, the race was never run again.

Mad Bull married, but his wife died. He returned to Happy Camp and mined gold and worked as a logger. He then married again to Beulah and had three children.

In 1938, an Austrian, Adam Ziegler, attempted the run solo and boasted that he would beat Flying Cloud’s record time. He said, “I’ll keep running to Grants Pass until I drop.” Ziegler kept his promise and dropped after five days when he was about ten miles north of Eureka. He fell unconscious and was taken to the hospital and slept for 17 hours. Doctors blamed his condition on “improper diet, not enough sleep, and improper conditioning.” Mad Bull and Flying Cloud had traveled to Grants Pass to greet him when he finished, but Ziegler game up the run and headed back to San Francisco. Since 1928 the highway had been shortened and as a result of $42 million of work in improvements to its grades.

Looking back nearly 50 years later in 1976, Mad Bull said he personally ran every step of those 480 miles but recalled that at one point, a competitor mysteriously covered 15 miles in one hour. He suspected that the runner got a short, high speed lift in a car. Asked about his car, he replied, “It was no good.” He pulled out his battered silver cup that was labeled, “The winner of the world’s longest marathon race.” He also found a letter of congratulations from the Redwood Empire Association that said, “We are indeed proud of our first Americans.” He then went outside and drove off in a 1963 Buick.

The 1987 Reenactment

As famous as it became in 1927, the Redwood Indian Marathon was all but forgotten except for in the local communities along the Redwood Highway that participated in or witnessed the event. But it was a key event in ultrarunning history that influenced C.C. Pyles’ “Bunion Derby” and other ultrarunning events in the future.

In 2021, a monument was dedicated to the history of the event near where the original finish line was located in Grants Pass Oregon (6th and G Streets). It was the project of E Clampus Vitus, a fraternal organization that erects similar historic monuments.

Sources

- Andy Milroy, North American Ultrarunning: A History

- Peter Nabokov, Indian Running

- Running in Hopi History and Culture

- Wayne Morrow, “Indian Redwood Marathon (Redwood Empire Run)”

- Tara Keegan, Masters Thesis, 2016, “Runners of A Different Race”

- Leon Loofbourow, In Search For God’s Gold

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland) Dec 22, 1926

- The Arlington Enterprise (Kansas), Nov 16, 1917

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Mar 25, 1927

- The News-Review (Roseburg, Oregon), Mar 25, 1927

- Oakland Tribune (California), Apr 25,26 Jun 1,6,14-16-21, 1927

- The Coos Bay Times (Marshfield, Oregon), Apr 25, Jun 18,23, 1927

- Spokane Chronicle (Washington), Apr 25, 1927

- Modesto News-Herald (California), May 17, 1927

- The San Francisco Examiner, May 18, June 9,12,13, 15,17, 19-23, 26,1927, May 24, 1944, Apr 8, 1984

- The Eugene Guard (Oregon), May 31 1927

- The San Bernardino County Sun, Jun 1,19 1927

- The Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), Jun 1, 1927

- Petaluma Daily Morning Courier (California), Jun 8, 15-17, 1927

- Napa Journal (California), Jun 9, 1927

- San Anselmo Herald (California), Jun 10, 1927

- The Klamath News (Oregon), Jun 10, 18, 23, 1927

- The New-Review (Roseburg, Oregon), Jun 10,15,17 1927

- The Californian (Salinas), Jun 14, 16 1927

- The Petaluma Argus-Courier (California), Jun 15-18, 25 1927

- Tulare Advance-Register (California), Jun 16, 1927

- Santa Cruz Evening News (California), Jun 17, 1927

- Ukiah Dispatch Democrat (California), Jun 17, 1927

- The Times (San Mateo, California), Jun 17, 1927

- Tulare Advance-Register (California), Jun 17, 21 1927

- Modesto News-Herald (California), Jun 18, 1927

- The Los Angeles Times, Jun 19,23, 1927

- Medford Mail Tribune (Oregon), Jun 20, 22, 1927

- The Napa Valley Register (California), Jun 21, 1927

- La Grande Observer (Oregon), Jun 21, 1927

- The News-Review (Roseburg, Oregon), Jun 21, 1927

- Eugene Guard (Oregon), Jun 21, 1927

- Morning Register (Oregon), Jun 22, 1927

- The Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), Jun 22, 1927

- The Bend Bulletin (Oregon), Jun 22, 1927

- Visalia Daily Times (California), Jun 23, 1927

- The Semi-Weekly Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), Jul 27, 1938

- The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), Feb 10, 1950, Oct 6, 1987

- The Times Standard (Eureka, California), Mar 12, 1972

- Redding Record Searchlight (California), Mar 20 1976

- Santa Maria Times (California), Oct 13, 1987