Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:15 — 41.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

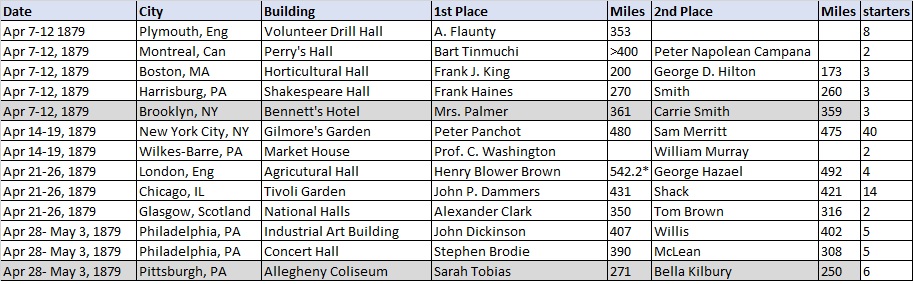

From 1875 to 1879, at least 130 six-day races were held, mostly in America and Great Britain. In 1879, the foot races became the #1 spectator sport in America. During that single year, at least 88 six-day races were held worldwide, with about 900 starters and witnessed by nearly one million spectators. Women played a significant role in these early six-day races, a century before they could take part in marathons. From 1875 to 1879, at least 30 six-day women’s races were held, involving 150 women starters who ran as far as 393 miles in six days. These daring women athletes caused a significant rift across the Victorian-era society. An editorial in the New York Times stated, “Today it is the walking match, soon the women’s vote will come.” It isn’t surprising that once the women competed, that New York City considered passing an ordinance banning “all public exhibitions of female pedestrianism.”

From 1875 to 1879, at least 130 six-day races were held, mostly in America and Great Britain. In 1879, the foot races became the #1 spectator sport in America. During that single year, at least 88 six-day races were held worldwide, with about 900 starters and witnessed by nearly one million spectators. Women played a significant role in these early six-day races, a century before they could take part in marathons. From 1875 to 1879, at least 30 six-day women’s races were held, involving 150 women starters who ran as far as 393 miles in six days. These daring women athletes caused a significant rift across the Victorian-era society. An editorial in the New York Times stated, “Today it is the walking match, soon the women’s vote will come.” It isn’t surprising that once the women competed, that New York City considered passing an ordinance banning “all public exhibitions of female pedestrianism.”

Many people thought these races, even limited to men, were a plague on society, especially because of all the wagering that took place and suspected corruption involved. In Louisiana, it was written, “Can’t someone up there give these lunatics some kind of creditable employment in which they can exercise their pedal extremities to their hearts’ content?” From London, England, “One of these days, when one of these poor fellows, dazzled with the distant prospect of gold, drops down dead on the track, science will be satisfied, sport appeased, and public indignation aroused. Pedestrians will go on doing the ‘best time on record’ until they drop down dead.”

After a huge race in New York City, The Third Asley Belt race, that affected attendance at churches that week, a minister wrote, “New York has been shamefully disgraced. This commercial emporium is in dishonor in the sight of God and in the eyes of the civilized world.”

These early pedestrians at first had a goal to surpass 500 miles in six days. They then kept pushing the six-day world record further until George Littlewood reached 623 miles in 1888. That record stood for nearly a century and was considered a running record that would never be broken. But it eventually was broken by one man. Today, the six-day world record is held by Yiannis Kouros, of Greece, who covered an astonishing distance of 635 miles on a track in New York City in 1984. Later, in 2005, he covered 643.

Running vs. Walking

In 1878, the British established a six-day world championship series of races called “The Astley Belt.” After the 3rd Astley Belt Race in early 1879, won by Charles Rowell of Great Britain, Daniel O’Leary, the former six-day champion of the world, spent a lot of time pondering how the British seemed to being exceeding the Americans in the six-day sport. He became convinced that no strict walker could ever again win a highly competitive six-day race against runners. The best strict heel-toe walkers could exceed 500 miles, but not much further. He believed the runners being developed in Britain could go much further than 500 miles, and it was time for Americans to learn how to run more during these “go-as-you-please” six-day races.

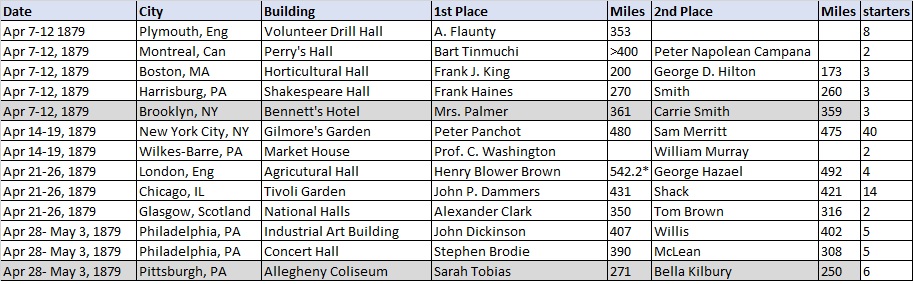

During April 1879, at least 13 six-day races were held, including five during the same week. Two significant races were held that month, the American Championship Belt at Gilmore’s Garden, New York City, and the 2nd English Astley Belt held at the Agricultural Hall in London.

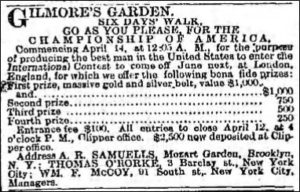

Plans for the American Championship Belt

Belts, not belt-buckles, had become the six-day championship award for the winner of these races. The belt was described as “38 inches long, five inches wide, made of seven heavy plates of gold and silver and bearing the inscription: ‘Champion Pedestrian Belt of the United States.’” Figures of runners were inscribed on two plates of the belt, some with wings or wheels for feet. The central plate featured large figures of the statue of Liberty and a native American.

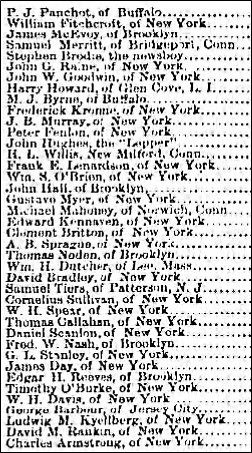

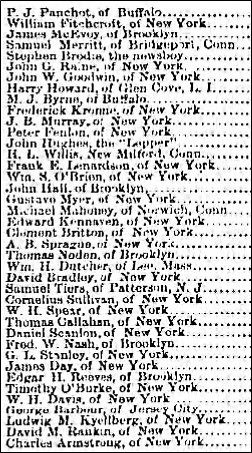

The organizers planned for 40 starters, which would by far be the largest six-day race ever held up to that point. This race was significant, because it was the first major race where the field was composed mostly of amateurs. The entries’ fee for this race was not as expensive compared to the previous six-day races, and thus a new crop of 36 six-day “greenhorns” entered the race. Only four others had six-day race experience. With all this inexperience, they risked causing a disaster.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, recalling how some spectators got clubbed by the police at Gilmore’s Garden during the previous month’s Third Astley Belt Race, wrote, “Tramps have begun walking at Gilmore’s Garden, but the people are beginning to understand that there is no law which compels them to go there and get clubbed for fifty cents”

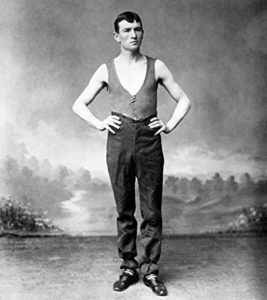

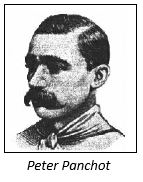

Runner Spotlight – Peter Panchot

He was inspired in 1878 by John Ennis to start running long distances and he competed in three-mile races. In May 1878, he got the attention of Buffalo when he won a 50-mile walk at the Pearl Street Rink in 11:11:33 and won again in June with 10:17:32. Also at the Rink, he walked 100 miles in 22:27:58.

In February 1879, he challenged William M. Hoffman to a 25-mile race outdoors in the streets of Buffalo for $100. It was watched by hundreds of people. Panchot won by a mile, finishing in 4:22:30. The following month, he raced Cyrenus Oscar Walker (1841-1919), for 50 miles indoors at St. James Hall. Panchot won the walking match by only four minutes, finishing in 9:05:40. He then entered the six-day race, Buffalo’s favorite undefeated local pedestrian.

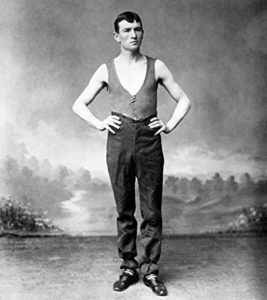

Runner Spotlight – Steve Brodie

In February 1879, at the age of 17, Brodie made his first attempt to break into the sport of pedestrianism when he walked 90 miles in under 24 hours in the gym of the Newsboys’ Lodging House. He quickly achieved youthful stardom in New York City and followed that up by walking 50 miles in 8:39:53 in front of 3,000 people at Eagle Hall, Hoboken, New Jersey. With that success, he was accepted to compete in the American Championship Belt.

The Start

The start of the race was delayed for an hour and that gave the 2,000 spectators a chance to walk around the place. “The Garden was damp, chilly, and uncomfortable, but the crowd amused themselves by walking over the floor, peering into the tents and starting the week’s supply of cigar smoke.” A large group of news boys took seats across from the scorers’ table, ready to cheer their fellow boy, Brodie. As the race director tried to make a speech, to boys shouted, “Brodie, Brodie, Brodie’s the man.”

The first to quit the race, at about mile 45, was Thomas Callahan, who worked as a dirt collector with a cart in the streets of New York. “Those who saw his pipe-stem legs wondered how they could have carried him over so much ground. He is satisfied that there is more dust to be picked up in the streets than on the sawdust track.” Ludwig M. Kyellberg, of New York City, was soon out too. “He had weakened himself with strong whiskey and had hopped around like a sick Piute in a war dance.”

Brodie ran close to the frontrunners, but started to look lame after the first day. “The newsboy, was the picture of distress, and notwithstanding the opinion of his attendants that he was ‘tough and all right,’ it was evident that only their ignorance and his own pluck kept him moving around the track.” He found his groove and continued to run strongly. The common joke people yelled at the newsboy was, “Are they getting out new extras?” He was often seen chewing away at a large sandwich as he plodded along. His gait was described as “a very slouchy manner, with his head hanging forward and his arms swinging violently.”

Day Two

Brodie was doing well. “The youngster was astonishing everyone.” He vowed to continue for the entire six days. He was a hero to all New York City newsboys. “Shivering newsboys, wet to the skin, stood in the half shelter of the building outside, inquiring eagerly of persons whom they supposed had just come from the inside. ‘How is Steve Brodie getting along?’”

“The presence of only about 200 spectators this morning is an indication that New Yorkers are beginning to tire of the spectacle of a number of weary men trudging around a dirty track.” It became especially boring when most of the runners were resting in their tents. The crowd would cheer loudly and shame the walkers to come out of their tents. They would then go around the track “like a flock of startled sheep.”

Days Three Through Five

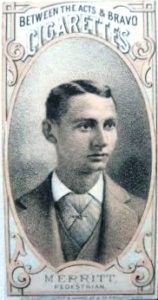

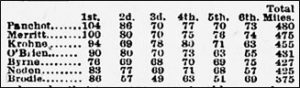

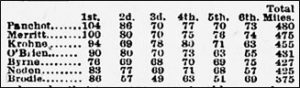

The only thing that kept the spectators’ interest was that the leader, Panchot, was at a better pace than Charles Rowell (1852-1909), the world champion, ran a month earlier at the Third Astley Belt race, but that pace would not last. It was said that many of the thirteen remaining walkers “looked fitter to be in bed than walking. The atmosphere was so cold and damp that several of the walkers were forced to wear coats. Everything had a dingy and dirty appearance. Bookmakers sat at their little tables vainly endeavoring to get bets. The crowd in the barroom drank in solemn silence and most of the imbibers had a looked about them of having been up all night.” In the evening, about 2,000 people came to watch. After four days, Panchot was at 337 miles, thirteen miles ahead of Samuel Merritt, of Bridgeport, Connecticut.

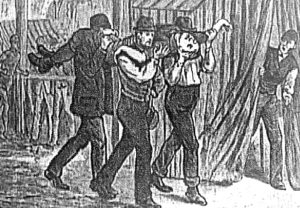

As the race neared its conclusion, young men tried to get into the building without paying for a ticket. “It was no little amusement to the spectators to watch the various appearances of heads at the broken windows, the stealthy entrances, and the sudden and ignominious ejection of the culprits from the gallery they had attained with such infinite pains by the police officers who lay in wait for the rascals as a cat does for a mouse.”

When Panchot completed his 400th mile, the band played “Yankee Doodle” and ten letter-carriers from the New York post office came out onto the track to present a letter of congratulations to their fellow postman, Panchot. “He smiled and bowed as he took it but did not pause an instant in his walk.” He hung the letter on the front of his tent. At the end of day five, Panchot was at 407 miles, only six miles ahead of Merritt. In a close race.

Runner Spotlight – Samuel Merritt

On February 8, 1879, Merritt won a six-day race, the Connecticut state championship against five other runners in Lyceum Hall, reaching 400 miles. “He was a tall ungraceful looking young man, who was described as having a shambling gait, bringing his arms in front of him with each step. However, with that method of progression, he could ‘run like a deer’ when it suited him.”

The Finish

Only eight out of the original 40 runners remained on the final day, proving that the 6-day race is not for inexperienced amateurs. It was said that the young newsboy Brodie was in the best condition of the eight runners who remained on the track. “Brodie, time and time again, ran around amid the cheers of the crowd.” He smartly would run around the track carrying a bundle of newspapers, which he autographed and sold to the spectators at exorbitant prices. His friends solicited newspaper subscriptions for him in the crowds.

William Buckingham Curtis (1837-1900), of Wilkes’ Spirit of Times presented Panchot’s his award and said, “You came among us a stranger, Mr. Panchot. We knew nothing of you, but you have earned the belt, which I am pleased to have the opportunity of handing over to you.” He also won $1,000. As Panchot left the building, he was given thunderous applause.

Reaction

Panchot beat the mark that Ennis ran during the Third Astley Belt race a month earlier, finishing in second. Ennis wrote, “Panchot has done a wonderful performance which places him in the front ranks of pedestrianism. Buffalo can justly feel proud of her champion.” American sportsmen hoped that Panchot would go to England to compete in the Fourth Astley Belt race.

Not everyone in New York celebrated. Rapidan wrote, “If the walking mania continues to catch victims, it will soon be as great a nuisance as baseball. One of the statesmen is making an effort to squelch it by introducing a bill making walking for money a misdemeanor, but there is no probability of its passage. The mania will doubtless run itself out if left alone.”

Sources:

- Los Angeles Evening Express (California), Apr 5, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Apr 6, 14, 16, 18, 20, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 6, 8, 17, 18, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Feb 9, Apr 14-20, 1879

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Apr 14, 15, 1879

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Apr 14, 1879

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Apr 15, 1879

- The Sun (New York City, New York), Apr 15, 1879

- Buffalo Courier Express (New York), Jan 15, Feb 2, Mar 19, Apr 18, 21, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Apr 20, 1878, Mar 20, 1879

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Jul 15, 1878