Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:06 — 32.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

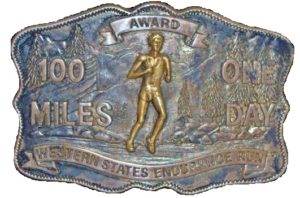

![]()

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

In Part One on Endurance Riding, I covered the very early history of the sport of endurance riding from 1814-1954 when forgotten individuals established the sport they called “endurance riding” and paved the future for the sport. In Part Two I covered the early history of the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup) from 1955-1970 and worked through some folklore about the history of the Ride. In this concluding part we will wade through some controversy and get to the ultrarunning fun, the founding of the Western States Endurance Run or commonly called, the Western States 100.

In Part One on Endurance Riding, I covered the very early history of the sport of endurance riding from 1814-1954 when forgotten individuals established the sport they called “endurance riding” and paved the future for the sport. In Part Two I covered the early history of the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup) from 1955-1970 and worked through some folklore about the history of the Ride. In this concluding part we will wade through some controversy and get to the ultrarunning fun, the founding of the Western States Endurance Run or commonly called, the Western States 100.

By 1970 with all the numerous endurance rides held across the country, the Western States Trail Ride, or “the Tevis” had emerged as being the toughest and the premier endurance ride in the country. It had survived intense criticism over the years from the public and animal rights groups. Under the leadership of Wendell Robie, the ride had made adjustments, weathered the storms of criticism, and increased in popularity.

By 1970 among the dozens of endurance rides, there were still only a few that patterned their event after the Western States Trail Ride, Virginia City 100, and two 50-milers in California, Castle Rock 50 and Blue Mountain 50. In 1971 two more were established, Big Horn 100 in Wyoming, and Diamond 100 in California which awarded a Wendell Robie Cup.

In all, across the country there were nearly 100 endurance rides of various flavors held in 1971. Some histories grossly under count and mislead readers into thinking there were just a handful of endurance rides in existence at that time. During 1971 there were at least 20 new rides established with distances between 25-100 miles and several of them were influenced by the Western States Trail Ride in one way or another. Some started to award belt buckles and some rode on tough trails. But most of these new “races” were doing their own thing. For example, the Wasatch Mountain 50 Mile Endurance Ride in Utah was particularly tough, doing loops near the present-day Wasatch Front 100 course with some big climbs. By 1971, endurance riding was ready to enter into a new era with the strong influence by those associated with the Western States Trail Ride.

North American Trail Ride Conference

Back in 1941, at Concord, California, an endurance ride was established by the Concord Chamber of Commerce, and was patterned after the Green Mountain Ride in Vermont. It was a two-day (later three-day), 80-mile ride going from the city of Concord on trails, winding across ranches, through wooded canyons, and along the slopes of Mt. Diablo. They emphasized that “to finish was to win,” that the last finisher could be the winner. This endurance ride in California was established 14 years before the first edition of the Western States Trail Ride in 1955.

Twenty years later, in 1961, members of the rider association in Concord established the North American Trail Ride Conference. That year in a newspaper article it was stated, “The purpose of the conference, or organization is to coordinate dates so there will be no conflicts, develop rules and regulations for member rides and riders, and generally help and promote new rides just getting established.”

With the many critics from influential organizations like The Humane Society, the NATRC emphasized looking after the “soundness of horses.” The NATRC said that their events were not “endurance rides” (but they really were). They also started to refer to their flavor of endurance riding as “competitive trail riding.” This semantic approach was used to distance themselves from the intense criticism that the Western States Trail Ride was receiving even though the Tevis claimed that it wasn’t a race (but it really was). The careful use of words was obviously part of a strategy to fend off attention and criticism from animal rights groups and the public. When the early NATRC events were announced in newspapers, the sanctioned rides made it very clear that their rides were not associated with races like the Western States Trail Ride.

The NATRC became successful and influential by 1970, sanctioning many events, and was careful to keep fairly true to long-established principles for endurance rides established long ago in Vermont. They did not want their events to be races. They established a point system awarded to riders in order to publish annual rankings and awards. Points went to finishers not to “first finishers.”

There was contention in the sport. The rides/races that started to be patterned after Western States Trail Ride were not sanctioned by the NATRC. There was heated disagreement about the racing aspect of events and what should be done to safeguard the treatment of horses. In 1970 there was also a split in the NATRC, and the Eastern Competitive Trail Association (ECTA) was formed in upstate New York, and started to sanction their own races.

Many of the new events cropping up in 1971 were not sanctioned by the NATRC, and were doing their own thing. Two horses died that year in a new 25-mile “Ride and Tie” race in California, again bringing serious public backlash on all types of endurance rides. Many Arabian horse breeders refused to sell horses to endurance riders. From the Western States riders’ point of view, something needed to be done.

American Endurance Ride Conference

In 1971 during this contentious environment in the sport, while a new 50-mile ride from Sacramento to Auburn was being planned, 25 riders from California and Nevada who were in in the “Tevis faction” met together led by Phil Gardner to discuss organizing a competing organization that would align better with their preferred form of endurance riding. Arguing resulted, but Gardner did soon create an organization and later in 1972 formalized into a legal entity as the American Endurance Rice Conference (AERC). Founders included Phil Gardner, Charles Barieau, Marion Robie Arnold, Kathie Perry, Todd Nelson, Hal Hall and Julie Suhr. Gardner was their first president.

Similar to the NATRC, the AERC started doing record keeping to preserve statistics and also ranked riders and horses. Eventually they standardized rules, started sanctioning rides, and controversially required sanctioning fees from events.

The original rules for an AERC sanctioned events described a limited definition for an endurance ride.

- The first horse to finish (in the least amount of time) in acceptable condition is the winner.

- An award for the best conditioned horse.

- There can be no minimum time limit.

- Everyone finishing a ride shall receive a completion award.

- The ride is open to all breeds of horses.

While Wendell Robie supported the idea of the establishment of the AERC by his rider friends, he had no intention of participating, paying fees, and letting his Western States Trail Ride be governed by the AERC or any organization. This created conflict and eventually the AERC even denied to sanction to his ride until a compromise was reached to gather fees from riders who wanted their results in AERC records.

AERC rides had a set distance, a finish order, and an award given to the “first finisher.” Any outsider would call that a “race,” but the founders of the AERC eventually chose to avoid at all costs the words “race” and “winner.” This subject was hotly debated by the AERC founders, most who wanted to preserve the racing aspect of their flavor of endurance riding. Eventually they adopted a motto of “To finish is to win,” a principle that actually grew out of the NATRC’s flavor of endurance riding as far back as the 1941 Concord Mt. Diablo Ride.

Curiously in the AERC’s crafted history, it appears that they totally broke away from their common history roots with the NATRC and proclaimed that endurance riding began in 1955 because that is when they believed their preferred format of endurance riding first emerged. Actually, it wasn’t until the mid-1960s that the” minimum time” was eliminated for good at the Western State Trail Ride. (rule 3). The riders for decades before 1955 called their sport “endurance riding” and Robie used some of the earlier endurance ride principles to help establish Western States Trail Ride. How could it all have started in 1955? It didn’t.

But, despite controversies and growing pains, the AERC lived on and was a huge stabilizing influence to the sport allowing it to be preserved and grow. The same can be said to NATRC’s contribution to endurance riding. By 1974 there were about 50 AERC sanctioned rides. Certainly because of the leadership of these organizations, endurance riding of all forms was able to better promote safety and certainly saved horse lives.

Let’s get back to the races that were called rides.

1971 Western States Trail Ride

In 1971 a young man, age sixteen, Hal Hall entered the now famous Western States Trail Ride. In 1969 when he was only fourteen, he attempted the ride but was in way over his head and didn’t finish. But he did finish in 1970, in 64th place. In 1971 he would ride again, for the third time.

Also In the field was a first-timer, a young, large athletic rider, 23-year-old Harry “Gordy” Ainsleigh, who rode on this eight-year-old horse, Rebel bareback. Staggered starts were used with small groups of riders starting together. Ainsleigh started in the 14th group, Hall in the 9th group. There were four key checkpoints in place that year with mandatory rest periods: Robinson Flat (one hour), Devil’s Thumb (half hour), Michigan Bluff (1 hour), and Echo Hills (1 hour).

Hall, young, fast, and eager, kept up with the leaders for many miles but at Michigan Bluff his horse was ruled lame and he was pulled out by the veterinarians. Hall would have to try again the next year.

Ainsleigh, disadvantaged because of his larger frame and weight would have to run many miles ahead or behind his horse to take the weight off and make faster progress. He finished at the fairground’s stadium, with a time of 19:37, about five hours after Donna Fitzgerald, the winner of the Tevis Cup. For that 1971 finish, 74 finished and there were another 76 riders and horses that did not finish for various reasons including: “lame horse, thrown off horse, lost horse shoe, disqualified (switched rider), fatigue, horse pulse too high, missed cutoff, and rider quit.”

For many riders it took multiple years to learn and succeed in earning a buckle with a finish in 24-hours or less. There was no handbook or training manuals to refer to. They learned from their failures and successes. The Friday before the ride each year, was both a stressful and exciting day for the riders. They would arrive at Squaw Valley and get their horses all ready and have them inspected by the veterinarians. Each year many horses would not pass the examinations. Being passed off to start was a huge initial victory.

Friday evenings were exciting. The rider meeting was held with all the last-minute instructions. That evening also was the social event of the year for the riders. It was like a big reunion when they could exchange ideas, tips, and get educated. It also was a big party with dancing and a lot of drinking, making it tough for some to feel ready in the morning for the start.

The riders could use crews to travel to certain check points and assist them, but in the early 1970s many riders did not have a crew at all. They prepared drop bags that were delivered. For example, multiple Ride champion, Donna Fitzgerald, did not use crews. She would organize duffel bags of supplies which were dropped off at each of the vet stops during the ride. Occasionally someone held her horse, or if her husband, Pat got pulled from the ride, he provided assistance. The early riders, similar to experienced ultrarunners, were self-reliant and did not use the massive crews that a majority of the riders of today deem necessary to ride their horse in the Western States Trail Ride.

1972 – The First Finishers on Foot

The 1972 Ride was very historic for a new reason. Wendell Robie allowed twenty soldiers from Fort Riley Kansas to come and test their endurance ability to try to cover the course on foot during the Ride. Their goal was to complete it in less than 48 hours. An “adventure team” had been organized at the Fort and they sought for a very challenging test. The wife of Captain Joseph McCarthy who was on the team, Mary McCarthy, had finished the Tevis in 1967. McCarthy had brought forward the idea to march the Western States Trail. Robie was contacted and he was enthusiastic about the idea. Captain McCarthy would be the commanding officer of the team and crew chief, Lt. Larry Hall would lead the team on the trail. They came out about ten days before the event to make plans with Robie.

McCarthy explained what the adventure team was all about. “The Army has a new program of providing its men with challenges that give them an opportunity to see the country. It is adventure training, providing an incentive challenge, rather than marching in circles.” About 30 soldiers were bussed out, 20 to march and ten to support.

Hal Hall, age 17, rode again. A group of worn-out soldiers had arrived at Michigan Bluff, about mile 60, right before Hall. He recalled, “They looked a bit whipped. Their faces were blush-red, they were sweaty, and generally looked tired. They were under a shady tree, most of them seated, and some laying on the ground. Some were shirtless as they filled canteens, and wetted bandanas for their heads.” Most of the soldiers dropped out along the way but seven were successful in marching all the way to the finish. Six finished with a time of 44:54 and another soldier finished in 46:49.

Hal Hall finished the ride for the first time on his Arabian horse, El Karbaj. He had been determined to do well and came in 2nd place. He won the Haggin Cup for the best conditioned top horse to finish.

At the awards banquet that Sunday evening, the finishing soldiers were presented with many awards including a trophy for the first finishers on foot prepared by Wendell Robie. One soldier said, “It’s a once in a lifetime thing! I’d never do it again unless I had to, but what a great sense of satisfaction to have finished.” The Fort Riley Post stated, “This was the first time the trail had been competitively traveled on foot with a time factor involved.” See Western States 100 on Foot: The Forgotten First Finishers to read details of their historic march.

Gordy Ainsleigh saw the soldiers and knew that they covered the course on foot, and he passed by the finishing seven during the early morning. He finished ten minutes quicker than the previous year.

Gordy Runs his First Ride

In 1973, Ainsleigh, knowing that seven soldiers had been able to cover the Western States Trail on foot, went to a 50-mile ride event to attempt to run it. In 1967 the Castle Rock Ride, patterned after the Western State Trail Ride, was established in Henry Coe State Park in Northern California southeast of San Jose. “Locals described [the ride] as a test similar to the famed Tevis Cup Ride in Placer County, except on a smaller scale.” By 1973 it was a 50-mile point-to-point ride that attracted riders from several states. That year it started on the Pacific coast beach near Davenport, California, went through Castle Rock State Park, and finished at a ranch in Los Gatos near San Jose. Ainsleigh successfully ran the course in about nine hours, finishing in the middle of the pack of riders who had two mandatory one-hour stops.

Gordy Runs the Western States Trail Ride

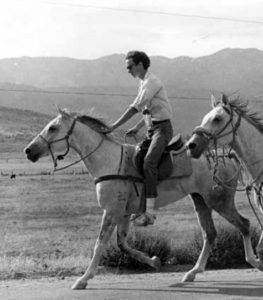

In 1973, Gordy Ainsleigh rode again at the Western States Trail Ride, but only made it to Robinson Flat (mile 30), which took him seven hours. His horse was lame and couldn’t continue.

He gave away that horse and intended to ride again in 1974 but procrastinated finding another horse. Dru Barner, Wendell Robie’s assistant, suggested and encouraged Ainsleigh to run the course on foot, to try and finish it in under 24-hours. She said to him, “We’re all wondering when you’re going to leave the horse behind and just do it on foot.” In the previous years when he would ride, he would run much of the course leading or following his horse.

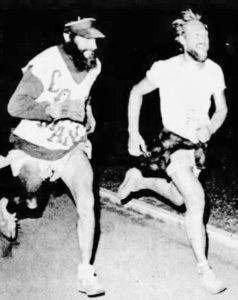

Just seven weeks earlier, he had teamed up to win the 42-mile Levi Ride & Tie Race with Jim Larimer of Auburn and Larimar’s Arabian horse, Smoke in Klamath Falls, Oregon. For “Ride & Ties,” two runners/riders and one horse, race to reach a finish line together. One person rides ahead, ties off the horse so it could eat and rest, and then runs ahead. The other runner catches up, rides the horse and continues the leap frogging to the finish. It took very skilled and fit runners and riders to win these competitions.

Ainsleigh decided to run the 1974 Western States Trail Ride and wanted finish much faster than the soldiers did two years earlier. In 1972 his running coach expressed the belief that no one could run that trail in under 24 hours. Ainsleigh believed otherwise. Wendell Robie, the “prime mover” in establishing Western States Trail Ride had his doubts if Ainsleigh could do it. He said, “It is probably a universal opinion that it is beyond the powers of human endurance to span the 100 miles of this rough mountainous trail on foot in a period of 24 hours, but Harry (Gordy) probably will make one or two of the control stations within the operational schedule.”

To train, Ainsleigh would get a car ride to Michigan Bluffs and then run to Auburn. He did that four times in six weeks. In preparation, a few days before the race, he rode his dirt bike to various points on the course and dropped off Gatorade that he would need during the run.

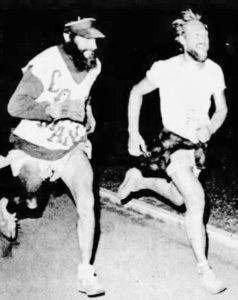

On race morning, Ainsleigh was given a good head start on the horses and tried to stay ahead of most of them for the first 30 miles or so to Robinson Flat. With all the single track trails in that section he didn’t want to be delayed by stepping off the trail to let horses go by, so he ran faster than planned. The horses then started to pass him as he slowed, but he passed them again as they slowed and took their mandatory rest stops. A kind timing crew gave him canned peaches at Last Chance and at Devil’s Thumb he was really struggling in the 107 degree heat. He had decided to quit because he was so drained and felt so weak. His sister was stopped there with a lame horse and recognized that he was dehydrated and suffering from hyponatremia. She revived him with salt and water. Thirty minutes later, he was on his way again.

From Michigan Bluff to the finish, he “panhandled” for food and liquids from plenty of people on the course. He stopped at one point to help some riders with a horse that had collapsed in the river. With 20 miles to go, he asked for a guide rider to help pace him to the finish. Many people were curious and betting on whether he could finish by 24 hours. As the finish came closer, he had been passed by the majority of the horses and was running amidst the riders and horses struggling to make the 24-hour cutoff in time.

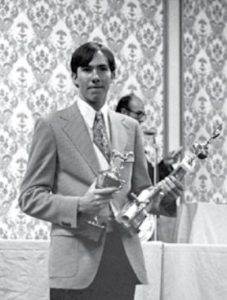

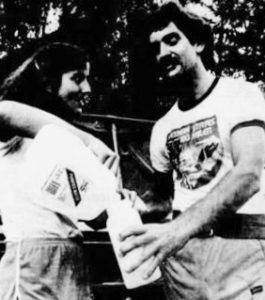

At the finish, at McCann Stadium on the Gold Country Fairgrounds in Auburn, Hal Hall, had finished six hours earlier and was the winner of the Tevis Cup that year. He was Ainsleigh’s friend and had gotten up several times during the night to walk his horse, in order to make sure it didn’t stiffen up. Hall went back to rest and asked someone to wake him up to witness Ainsleigh’s finish. Around 4:30 a.m., exciting news arrived that Ainsleigh was close to the finish.

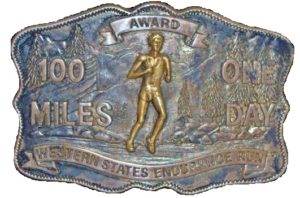

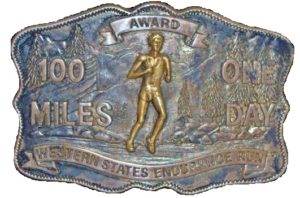

Ainsleigh entered the stadium, did a somersault and headstands before the finish line, and crossed with a time of 23:42. There were lots of cheers and congratulations. He became the eighth person to cover the course on foot and the first to break 24 hours.

Ainsleigh would become the icon of the future Western States 100 and the founders would make sure to “cement Gordy’s place in history.” For the next 44 years he was incorrectly credited as being the first to cover the course on foot during the Ride until the story of the soldier’s march was brought into the light and told in 2018. Nevertheless, Ainsleigh would be a great ambassador for the sport, and the story of his 1974 run would be the most legendary story in ultrarunning.

The Western States Trail Run

The 1977 race was organized by the rider organization, The Western States Trail Foundation with Ainsleigh given the race director role. He had talked about putting in a qualifier requirement that the runners had to have completed a marathon in at most 3:15. He said, “We don’t want anyone who isn’t a good runner.”

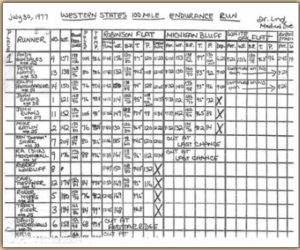

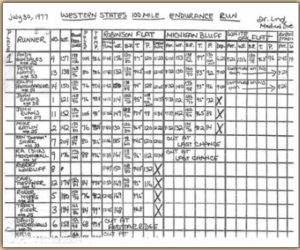

Mo Livermore and Curt Sproul were the race managers. Shannon Weil, an experienced finisher of the ride, was invited to help with the run. The four horse inspection stations were utilized as aid stations and the veterinarians would check the runners as they came through.

1977 was the only year when the Run was held concurrently with the Ride. It turned out to be the hottest day of the year. 200 riders and 14 runners started. If a runner wanted to pass a rider they would yell “Trail.” Weil rode along on her horse monitoring the runners and rode the final 40 miles with the front-runner and eventual winner, Andy Gonzales, who set the course record in 22:57. Only three runners finished. The other two finished in more than 24 hours. That helped race staff to consider extending the finish cutoff time the next year to 30 hours. Hal Hall won the the Tevis Cup again that year.

The 1978 Run

Planning for the 1978 Run became more serious and better organized. The Western States Endurance Run Board of Governors was formally organized by Robie and the key participants were horse endurance riders, Shannon Weil, Mo Livermore, Curt Sproul, and Phil Gardner, called affectionately “the gang of four.”

Because of the difficulty experienced in 1977 with both runners and horses on the same trail, especially with single-track sections, the run was moved to the month before the ride. Weil worked at Robie’s bank and made calls to get the word out and fielded calls from interested runners, marketing the run mostly by word-of-mouth. In a 1978 Runner’s World magazine, an advertisement was included that read: “Western States 100-mile Endurance Run. An experience only for ultramarathon veterans. Course: rugged, uncertified over mountains, through streams, with snakes and bears. All entries must pass physical exam. No one under 18. 30-hour time limit.”

Weather was good in 1978 but there was snow in the high country to run over. There were 63 starters, including five women, and there were 30 finishers. Fifteen finished in under 24 hours. There were 21 aid stations that year, including six medical checkpoints. Steve Mason of Reno lost the trail but was found by rangers and race crew at 7 a.m. on Sunday. He went on to finish in 29:38.

70-year old Walt Stack finished in 38:47 and was listed in the official results. Stack described the experience, “It was by far the hardest race for me. You have to run in the dark with flashlights, and carry a rattlesnake kit. Eighteen miles of the course is on snow. You have to run through creeks and get your feet wet. There are no running trails, just horse trails. My feet were so damn sore.”

Twins Peggy and Karin Stok got lost and mile 92. Peggy said, “You get what’s called runner’s daze. The rocks looked like they were playing a movie and I clearly heard the river talking.” They were eventually found by some campers who led them out of the woods. Ainsleigh was accompanied by a dog the entire way, “Merlin,” an Australian shepherd.

That year Andy Gonzales won for the second year with 18:50. At the finish, Weil said that the finishers looked “brutalized,” but the race that year was a huge success. Robie was ecstatic and told Weil that they had “caught a bear by the tail.” He knew the race would become a very big deal. Weil proclaimed that with both the ride and the run, that Auburn was “the endurance capital of the world.” The Run did take off. Other mountain trail 100 race organizers soon contacted Weil, including Old Dominion and Wasatch Front, to pick her brain about organizing and conducting trail 100s.

The 1979 Run

In 1979, Western States was off and running with 143 starters, 96 finishers, and 67 of them in under 24 hours. It was being billed as “the toughest footrace in the world.” The entrance fee increased to $50.

Runners still had not figured out how much to carry. Bill Minturn carried two quarts of water with him. He recalled taking a wrong turn following footprints to a log cabin where an old prospector sat behind a barbed-wire fence and yelled, “Get out of here! You’re not supposed to be in here.”

Vandals removed yellow trail ribbons and many runners got lost during the night that year. The Foresthill Safety Club was called out to search for one runner. Another runner wasn’t found until 12 hours after the last finisher, at a remote forest ranger station, miles from the course.”

Many of these runners experienced running in the mountains at night for the first time. Michael Witwer said, “You feel like you’re being hypnotized because of running in the dark so long. Mild hallucinations would occur. You start seeing things. You see, for instance, a deer cross in front of you and then you realize it didn’t happen at all. Just occasionally you snap back into reality.” Witwer lost the trail three times and believed he ran an extra six miles. He said, “I looked for shoe prints to figure out whether runners were doing the same things I was.” Lono Tyson added, “We had to get down on our knees with our flashlights to check the trail for tracks. You start imagining things in the dark, like I thought I saw a rattlesnake, but it was stick. It was nerve wracking all night long.”

Witwer and Tyson did have a scare running through the mining town of Foresthill. Witwer said, “It was one of the few places where we ran on pavement. There was a bar there and some noise. Then some trucks pulled up in front of us and I heard three or four rifles cock. I thought, ‘What a way to go, after surviving 80 miles, to get my head blown off.” It turned out to be a local feud with no shorts fired.

Runners had their vital signs checked, including blood pressure. If their weight went down 10%, they were pulled out of the race. A few willing runners even submitted to rectal temperature readings in a little canvass privacy enclosure. Doctor Robert Lind, an emergency doctor from Roseville Hospital was in charge of the medical staff. He had many medically trained people show up to help at six medical checkpoints.

High school track volunteers had to carry some competitors out of the last deep canyon at No Hands Bridge above the American River. One teen said, “A lot of runners were barely coherent when they came by us at the 85-mile mark. It was crazy.”

Mike Catlin won with 16:11 despite over sleeping too long and starting ten minutes late. Doug Latimer finished in second, about 22 minutes behind. He was competing for the win but explained that he crashed around mile 85. “I started losing control. My legs were buckling under me. I fell down trying to walk. I had cramps and spasms at Diablo Canyon. By White Oak Canyon (the last major check point) they were severe, like electric shocks.” A woman, Skip Swannack, of Redwood City, California, became the first woman to finish in less than 24 hours with 21:56.

Mo Livermore and Curt Sproul, both veteran Tevis riders who served on the Run board ran that year. Curt finished but Mo dropped at mile 58. She said, “Being a runner makes you respect the horse as an athlete. I think you really run into trouble when you start looking at your horse as a vehicle.”

It was said that the awards dinner “took on the appearance of a POW camp, the runners hollow-eyed, speaking haltingly, walking stiff-legged, hobbling around with bandaged feet and knees.” Catlin summed up the Western State 100 experience, “Is it crazy to run 100 miles in a day? To some people it is, but for me, certainly not. It’s a great thing to do.”

Both the Western States Trail Ride and the Western States Endurance Run became amazingly successful but curiously for both, their place in history has been overstated by some. Contrary to popular belief the Ride was not the first endurance ride and the Run was not the first ultra. It also wasn’t the first trail ultra, and it wasn’t the first 100-miler. Ainsleigh didn’t invent the sport of trail ultrarunning as he has claimed. But the Western States Endurance Run was the first mountain trail 100 and it very quickly became recognized as the premier 100-miler in the world.

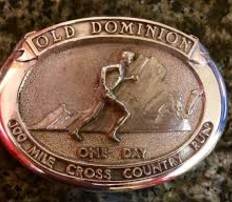

Old Dominion 100-Mile Endurance Ride

Alex Bigler, who had been a member of the Board of Directors of the Western States Trail Ride, moved to Northern Virginia and brought with him a desire to organize an endurance ride in Virginia. Others helped him and an organization was formed under the name “Old Dominion 100 Mile Endurance Ride” with Alex as president.

In 1974 the Old Dominion 100-Mile Endurance Ride was established patterned roughly after the Western States Trail Ride. The ride began and ended in Leesburg, Virginia and went through land with historic significance. It circled and climbed the Blue Ridge Mountains and went on the Appalachian Trail. It then traveled through many rural villages before returning to Leesburg.

The ride in the early years had a cavalry theme, awarding a Cavalry Award for the rider and horse that rode the ride with the least outside assistance. For the first few years, there was no award for the first to finish, instead they focused on “To finish is to win.”

In 1974, Don Cromer, a veterinarian from Churchville, Virginia, rode his black stallion, Mack in the first Old Dominion ride. He said, “We trained for four months and rode 78 miles a week. We used the back roads and different farm trails but there was just no way to really be prepared for what faced us at Leesburg.” Don wanted to start in the last group because Mack was slightly unsettled among all the horses. “It looked like the start of a posse when the first group broke from the starting line. They were going at a full gallop. But I wanted to pace myself at eight miles an hour. They had 10-minute stop breaks and then three, one-hour forced stops. The horses were checked and their breathing checked to see if they could continue.”

Don continued, “The ride was through rough mountain country, some of which was very steep. It included numerous water crossings and logs across the trail. But Mack never once quit on me. He was always willing to go one. It was tough following the trail at times, especially after dark. A lot of it went across private land and a number of markers were knocked down by cattle. You had to be on your toes to keep on the right trail.” Don finished in 23:40, total time. There were 24 finishers among the 51 starters that year.

In 1979 a concurrent 100-mile endurance run was added by Pat and Wayne Botts. For the inaugural run, 45 runners started and only two had experience finishing a 100-mile race. The run began at 4:15 a.m. Ray Krolewicz led most of the race but sprained his ankle while running and talking to a pretty girl on a horse. Peter Monahan won in 17:56. There were 18 finishers that year in under 24 hours.

In 1980 Frank Bozanich won Old Dominion 100 with a very speedy 15:17, which was the fastest trail 100 miler time up to that point. That year the horses were given a 45 minute head start on the runners, but Bozanich still beat all but six horses to the finish.

Vermont 100 Mile Endurance Ride and Run

In 1989, the Vermont 100 Mile Endurance Ride and Run was established, using many of the same roads and trails established by the original Green Mountain Horse 100 Mile Ride. A concurrent 100-mile trail race was conducted with a new one-day 100-mile ride. While this was a different event than the original 100-mile Green Mountain Ride, both rides shared the same tradition and local Vermont heritage, originating from the same town.

In 2018, The Green Mountain Horse Association 100 Mile Ride was still held on Labor Day weekend and was its 82nd year.

Roots for Ultrarunning

Today’s ultrarunners should feel indebted to the endurance riders for paving the way toward the establishment of trail 100-mile races. A common kinship is felt between the two sister sports. The trail 100s inherited many of the same procedures of aid stations, course markings, trail work, crews, medical checks, and of course the belt buckle award. Many thanks goes to the riders and especially to the late Wendell Robie.

Sources:

- AERC History

- Karen Bumgamer, America’s Long Distance Challenge II: New Century, New Trails, and More Miles

- Western States 100-mile Endurance run website

- Results and history of the Tevis Cup

- North American Trail Ride Conference

- American Endurance Rice Conference

- Eastern Competitive Trail Ride Association

- Tom Bache, AERC History: Traditions & Myths

- Phil Gardner, How it All Began

- Quicksilver Quips June 2017

- Old Dominion Equestrian Endurance Organization

- Old Dominion Run

- Vermont 100 Run

- Concord Mr Diablo Trail Ride Association

- The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, CA), Sep 18, 1942, Aug 16, 1979

- Arizona Daily Star, Jun 4, 1961

- Oakland Tribune, Aug 22, 1962

- Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, CA), May 15, 1969

- Auburn Journal, May 18, 1967, Jul 20, 1972, Feb 1, 1974, Jul 31, 1974, Jul 18, Aug 3, 1977, Jul 11,13, 1979, Jun 26, 1986, Jun 19, 28, 1978

- The Daily Messenger (Canandaigua, NY), Mar 24, 1970

- Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 15, 1970

- The Times Standard (Eureka, CA), Jun 10, 1971

- Red Bluff Daily News (Red Bluff, CA), Jul 6, 1971

- The Daily Herald (Provo, UT), Aug 19, 1971

- The News Leader (Staunton, VA), Jun 26, 1975

- Hattiesburg American, Jul 30, 1978

- The San Francisco Examiner, May 2, 1979

- The Pacer Herald (Rocklin, CA), Jul 12, 1979

- The Los Angeles Times, Jul 13, 1979

- Auburn Journal, Aug 3, 1972, Section C, “Camera Highlights of the 100-Mile Ride – And Walk!”

- Fort Riley Post, “Seven Air Defenders finish 100-mile hike,” August 11, 1972, 1-2

- 2017 interview with rider, Hal Hall, 30-time finisher and past member of the Western States Trail Foundation.

- 2017 interview with rider, Rho Baily, past member of Board of Governors for the Tevis Cup.

- 2017 interview with Shannon Yewell Weil, co-founder of Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run and Trustee for 30 years.

- 2014 Western States history presentation by Shannon Yewell Weil at the 2014 Western States Training Weekend. This Will Never Catch On: The birth of an Icon

- 2012 Gordy Ainsleigh podcast