Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:27 — 35.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

Frank Hart, at age 22, broke through racial barriers with his fourth-place finish in the 5th Astley Belt Race in Madison Square Garden, held in September 1879. Despite being black, Hart became a local hero in his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts. He had proven himself worthy of praise, competing on the grandest sporting stage in the world.

The ultrarunning/pedestrian promoters, backers, and bookmakers had allowed for diversity in this most popular spectator sport in America of that time. But was an American public ready to accept a black champion, just 15 years since the end of the bloody Civil War, with racial bigotry still prevalent in nearly all aspects of society? Hart, an immigrant from Haiti (see Part 1), had not grown up in slavery, and had the determination to reach the highest level of the sport in 1880, if he would be allowed.

Hart also needed a manager/agent. He again turned to a very young, unproven, but dynamic talent. He hired nineteen-year-old Jacob Julius “J.J.” Gottlob (1860-1933). Gottlob, a commercial traveler and theater man with west coast ties, took interest in pedestrianism. He would become known as the “Dean of Pacific Coast Theater managers.” As he acquired money, he would be Hart’s backer for several years.

The Rose Belt

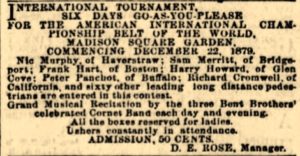

With these two young men to look after him, in December 1879, Hart went to compete at the next big six-day tournament, the “Great International Six-Day Race” or “Rose Belt” held in Madison Square Garden in New York City. The manager of the race was Daniel Eugene Rose (1846-1927) of New York City, a pedestrian promoter and owner of the D. E. Rose cigarette manufacturing company. This was perhaps the largest six-day race in history with 65 starters.

An expensive Rose Belt, valued at $400, was created for the winner, with seven rectangular sections. The center section included a globe with running figures and colored flags, and the words, “American International Champion of the World.”

About 200 scorers were employed. Scores were displayed on dials for each runner. Each runner had a big number both on their chest and on their back. Hart was not the only black runner in the field, there were three others, Edward Williams of New York City, Paul Molyneaux Hewlett (1856-1891) of Boston, and William H. Jacob Pegram (1846-1913) of Boston, who would often run together with Hart on laps. Pegram was a former slave from Sussex, Virginia. He won a small 60-hour race in Brighton, Massachusetts against whites, a month before Hart started competing. Pegram spoke in a thick southern black dialect that at times was mocked by the press.

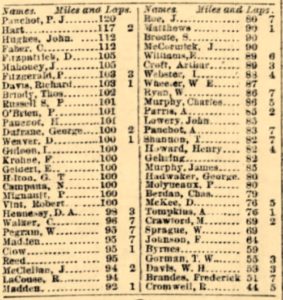

After the first day, December 22, 1879, Hart was in second place with 117 miles. On day two, after Peter J. Panchot (1841-1917), of Buffalo, New York, withdrew from the race, Hart took over first place. By evening, only 48 of the 65 starters remained in the race.

On Christmas Eve, day three, the race continued, and Hart lost the lead in the evening to Christian Faber (1848-1908), of Newark, New Jersey, when he went to get some sleep. Grumbles were heard by those with wagers on Hart, worried that he would not return. But Hart had not had very much sleep and needed it badly. He returned at midnight to kick off day four. Ten more runners chose to quit and celebrate their Christmas away from the Garden.

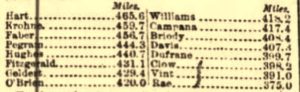

The largest crowd came out on Christmas Day (day four), with 7,000 people. “Hart looked the most wearied, and all his friends began to lose hope.” He was in third place, but only two miles behind the leader. At 9 p.m., Hart, in his familiar striped suit, finally retook first place which caused the crowd to cheer. Hart’s new trainer, Happy Jack Smith was pleased with his runner and said he was in “tip-top condition, determined to do or die.” His goal was to exceed the 530 miles that Charles Rowell reached during the 5th Astley Belt a few months earlier. But his friends hoped that he would reach 551 miles, which would break Edward Payson Weston’s world record of 550 miles.

Only 19 runners remained in the race. “The crowd at midnight had dwindled to a few hundred, and a good proportion of these were stretched out on the upper benches for an all-night’s sleep.” Hart maintained a lead of six miles on day five which was close enough to push him hard.

On the last day, running through air foul with tobacco smoke, Hart became very excited when he reached his goal of 531 miles. “Hart was swinging around with an American flag amid tremendous cheering, that was aroused by a dog trot into which he struck with the ease and lightness of a fresh man on the track.”

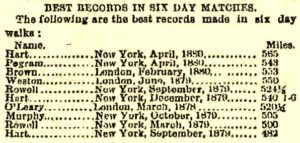

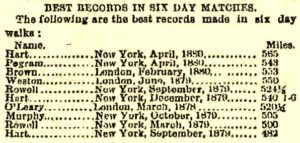

Hart, fueling on champagne diluted in seltzer, cruised to victory wearing a white flannel suit, with a blue jockey cap on his head. He reached 540.1 miles, running the last lap with the Rose Belt around his waist, carrying an American flag. Cheers rang out that shook the building. His mark was the third-best six-day mark in the world at that point and the best accomplished on American soil. Eight runners had exceeded 500 miles in the race. Three of the black runners finished in the top seven. Hart had established himself as a world elite ultrarunner and went away with at least $3,000 of winnings and the Rose Belt valued at $400.

It was challenging for large crowds to exit Madison Square Garden because of its few narrow doors. “There was a tremendous crush at all the doors when the crowd was leaving the Garden. At the Madison Avenue exit, two women fainted. They were carried into the street by their escorts, and were taken to a neighboring drug store, where restoratives were applied.”

Sadly, one of the contestants, Clarence G. Howard (1859-1879) who had withdrawn from the race on day one after 75 miles, feeling sick, died four days later at his home on Long Island. “Everything possible was done to save him, but without avail, and he died from utter exhaustion. He was more like a schoolteacher or a man of sedentary employment than a professional walker.”

Reaction and Racism

The New York Daily Herald wrote, “The promise of the young negro Hart to become one of the leading pedestrians of the world was handsomely fulfilled on Saturday night when the boy retired from the track with 540 miles to his credit.” The reporter speculated in the racist attitude of the day, that Hart was successful because he was “docile and obedient” to his trainers late into the race and gained his perfect walking method from his “master,” O’Leary. But the article then admitted, “As for Hart himself, his manners and achievements have made him as popular as any pedestrian in America and he may confidently challenge any other pedestrian in the world.”

When seen the next day, Hart said, “I felt rather stiff in my joints when Jack Smith, my trainer, pulled me from my bed and had a sort of headache, which I suppose is due to the wine I drank last evening to keep me awake. A spin of a mile or so though put me all right.”

Hart returned to Boston by train and was greeted by a large crowd at the Old Colony depot. A few days later, a nice banquet was held in his honor with many dignitaries giving flattering speeches.

Much of the nation was astonished that a black man could rise to be the greatest American athlete in the most popular spectator sport of that era. The Boston Globe wrote, “We have heard it said that the negro was incapable of noble endeavor. Hart has proven the lie to this assertion, for he has not only vanquished 49 white men but beaten the remaining sixteen who pluckily continued on the track. Great deeds accomplished by one man tend to raise the race to which that man belongs in public estimation. Hart’s success must be a natural spur of grand and nobler achievements. His great zeal, devotion, and honesty of purpose displayed on every occasion, he has earned for himself the exalted position of champion of America, if not of the world.”

In addressing the racism of the day, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote, “Mr. Hart has shown conclusively that there is nothing in a black skin or wooly hair that is incompatible with fortitude. The idea that our colored brother is an inferior will never sustain so severe a shock at the hands of the logician as it will when a colored man proves his physical equality as Hart has done. In the contest which ended last night, there were Americans, Englishmen, Irishmen, and Germans and this colored boy showed that he was above their average.”

Hart was now very rich, with winnings of at least $5,000, valued at $145,000 today. He believed that his financial backers had cheated him of some of his past earnings. One reporter warned, “He is in danger of falling into bad hands, owing to a disposition to be guided by other people instead of relying upon his own knowledge.” He became determined to take ownership and be his own backer. In January 1880, he looked at proposals to compete in San Francisco and then in Australia. He participated in some exhibition runs and announced intentions to run in the 2nd O’Leary Belt to be held in April 1880 in Madison Square Garden.

On Feb 26, 1880, a son was born to the Harts in their home at 26 North Anderson Street in Boston. They named him William Walter Hart. Hart gave his occupation on the birth record as “Pedestrian.”

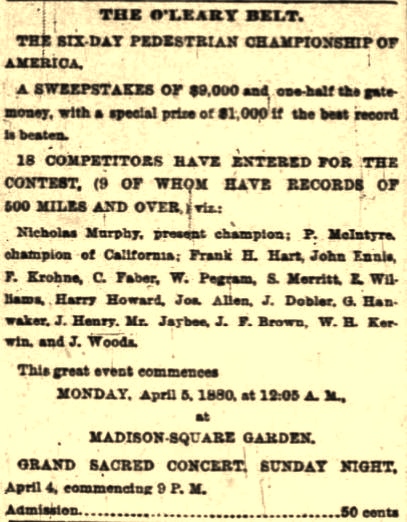

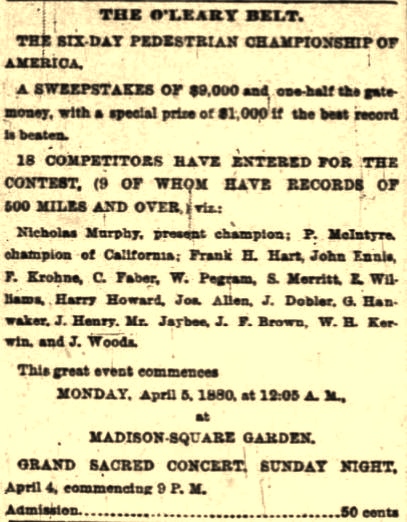

The Second O’Leary Belt

Daniel O’Leary established the “Oleary Belt” six-day race series in October 1879 as an American championship alternative to the Astley Belt Race. The British had too much control over the Astley Belt series and this American version could prepare American runners to compete on a world stage without traveling to England. The O’Leary belt race series could only be competed in America. The first O’Leary Belt was won by eighteen-year-old, Nicholas Murphy (1861-1904) of Haverstraw, New York, who reached 505 miles. Six months later, it was time for the Second Astley Belt race.

At 11:30 p.m., on April 4, 1880, Hart, age 23, entered Madison Square Garden and walked around the track to his tent while given loud applause from 6,000 people. He was confident that he would win and was a 3-1 favorite among the betters, and had boasted to the press, “I’ll break those white fellow’s hearts, I will. You hear me!” At midnight, all the 18 starters lined up and pedestrian promoter and referee, William B. Curtis (1837-1900) shouted the word, “Go.” The competitors went off on a trot or dead run, with Edward Williams, another black runner, finishing in the first mile in 6:20 with the lead. After an hour, the third black runner, William Pegram, was in the lead. He had been called, “the dark horse” of the race. By morning, nearly 8,000 spectators filled the Garden. At the rail, the beer-drinking, and cigarette-smoking men puffed their smoke into the faces of the plodding pedestrians as they passed by.

“Pegram and Williams, the dark team of Hart’s nationality, moved steadily and untiringly in the procession, at times working up and making a tandem with Black Dan as leader.” Some commented that Hart was coaching Pegram as they ran.

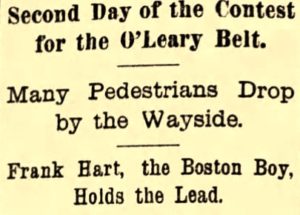

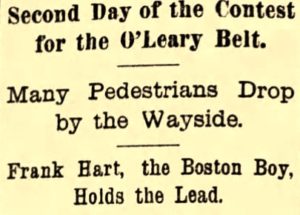

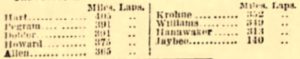

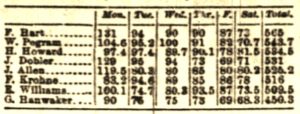

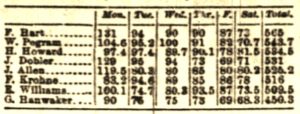

Hart reached 100 miles in 16:58:55 and covered an amazing 131 miles on the first day. He held first place by two miles over John Dobler (1859-) of Chicago, who had been training with O’Leary and had been dogging Hart’s steps. “Hart’s fine form, together with his stylish elastic walk and graceful carriage, won him much favor among the fair sex. He has since the last walk grown a mustache.” He finished day two with 225 miles.

Some observers closely watched Hart to find possible flaws. But what they found was impressive. “Hart is of a bright and happy temperament. He was always ready to look at whatever was going on, to chat with a contestant and glance in the direction from which an encouraging shout came, to give a weary plodder a kind word and helping arm, and to laugh at the fun which was going on.”

On day three, Hart feasted primarily on beef tea, mutton tea, and chicken tea. He also ordered quail on toast. “An hour later Hart was seen crunching a big piece of pie, the crust of which shone with grease. Although traveling fast, he took a mouthful about every three steps, with seemly great relish. His food is kept outside of his tent in a refrigerator and either Happy Jack or one of his assistants keep an arm over it constantly.” He reached 300 miles in an American record 66:28 and finished off the day with 315 miles, three miles behind Dobler.

Final Three Days

Day four presented a furious battle between Hart and Dobler. “The sharpest struggle of the race took place. Dobler began to quicken, and Hart followed. Lap after lap was covered and still the young Chicagoan hurried the work, which evidently began to surprise Hart, who was immediately behind him.” By mid-morning, the battle seriously exhausted Hart.

Later in the day, Dobler “hit the wall” and broke down, allowing Hart to build a double-digit lead in miles by late evening. The smoke in the Garden became terribly thick. When the walkers finally complained, the windows were opened.

It soon was discovered that smoke was coming up through cracks in the floor of the scorer’s box. A smoldering fire was found below that had been lit by a watchman trying to warm himself. It was put out and they were lucky it didn’t spread throughout the building. Hart finished day four with 405 miles, ahead of the world record pace, and a 14-mile lead. The press was amazed to see the two black runners, Hart and Pegram leading the race. When Hart started to have fainting spells, his trainers gave him stimulants and a “magic sponge” to revive him.

On day five, Hart concentrated on keeping his lead over his friend Pegram. They raced hard against each other for about seven miles during the morning without a break. “Although Hart was literally 13 miles ahead in the journey, he dogged Pegram’s footsteps relentlessly. Pegram lost his temper at times, occasionally throwing his broad feet backward like scoops and showering Hart’s legs with sawdust. Hart took this good-naturedly, retaliating by giving Pegram a brisk brush once in a while.” Runners could reverse direction for the next lap at the scorers’ table whenever they wanted. Hart would at times reverse direction without Pegram immediately noticing, causing him confusion and to the delight of the laughing crowd. At the end of day five, Hart reached 492 miles, with a 19-mile lead over Pegram.

World Record

As Hart started the final day, he struggled. Happy Jack Smith said, “At first, Frank was terribly sick and tired. He didn’t want to work. He was awful leg weary. But he said he had to get that belt, and he went on.”

Hart reached 500 miles early in the morning, two miles ahead of the world-record pace. His tent was nearly hidden by all the flowers that had been presented to him. He reached 550 miles with about six hours to go. “This was the signal for a perfect storm of applause from the men and boys, while the women waved handkerchiefs and shook their fans in a perfect frenzy of excitement. As he neared his tent, in the next lap, the colored favorite grasped an American flag from the hands of one of his trainers and ran at a lively gait around the track for the next lap, waving the flag in the air, amid the yells and cheers of the crowd.” The Garden was packed to capacity including many black spectators who had come to witness Hart’s victory.

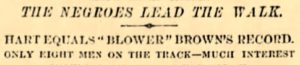

Three miles later Hart broke the world record of 553 miles, set by Henry “Blower” Brown (1843-1900) of England, two months earlier in London. This earned Hart a $1,000 bonus. “The yells and cheers which greeted him shook the building with their volume. Reaching his tent in the midst of the applause, he grasped a broom to which a flag was attached and ran the next lap as nimbly as a deer.” Another described the sound as “it was more like a series of bloodthirsty war whoops than the cheering of a civilized multitude. Hart came bounding along like a yacht under full sail.”

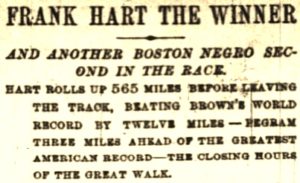

He didn’t stop, wanting to pile up more miles. When he reached 560 miles, all eight runners still on the track joined him for a lap. Hart ran with a silk jockey cap of many colors that a spectator gave to him. For his final lap, he wore the O’Leary belt and waved the stars and stripes as the band played “Yankee Doodle.” He finally retired after 141 hours and 23 minutes, with 565 miles, beating the previous world record by 12 miles.

O’Leary believed that Hart would break 600 miles someday. He said, “I am sure that he has not yet put his best foot forward. Look out for him in the next match.” Pegram reached 543 miles, for the third-best six-day score ever accomplished by an American up to that point, and the second-best performance on American soil.

Hart was driven by horse carriage to a Turkish bath, and after a nap of a couple of hours was taken to his agent’s home nearby. “His trainer said that he had not a blister, chafe, or strain anywhere, and was good for another day’s work at least as brisk as any he had done in the contest.” Hart won an estimated $21,567 (including a wager on himself) valued at $627,000 today. His winnings so far during his running career exceeded $860,000 in today’s value.

The next day, when visited by a reporter, he was quietly smoking, sitting near a table displaying both his belts, the Rose Belt and the O’Leary Belt. “Hart looked the very picture of contentment with a quiet, easy dignity that well befits all heroes.” He was surrounded by his agent, Gottlob, and his trainer, Happy Jack Smith. Daniel O’Leary arrived and they left together arm-in-arm to go celebrate at Putnam House with Pegram.

Reaction

There was a stunning racist reaction across the country that a black runner was the best ultrarunner in the world. In Louisiana: “Hart, the negro tramp, is the colored lion of the hour in New York. His legs have shown remarkable sustaining powers, and ladies give him bouquets.” In Indiana, “The colored man’s foot is not a thing to be despised. The negro walker carried off $16,000. Many a white man with a head full of brains never earned that much money in all his life.”

In St. Louis, Missouri: “It is eminently proper that in a contest of this character that the honor should fall to a race celebrated for its physical accomplishments, as opposed to intellectual.” In Kansas, “Legs pay better than brains every time. We, however, can’t advise young men to cultivate a growth of legs rather than brains.”

In England it was written, “The negro has now reappeared to public view in a new light. He has proved himself the ‘champion long-distance pedestrian of the world.’ This being an honour recently warmly contended for by many white men, it necessarily follows that to secure it must be a mark of unquestioned merit in the coloured men.”

In Cleveland, Ohio: “It has always been claimed that the negro race was inferior to whites in every respect. But it appears that result of this match, that the negro race may lay claim to physical superiority to the white, in endurance of prolonged muscular exertion as in this walking match, and in the power of resisting tropical heat. The black race is evidently developing rapidly.”

Tennessee described a reaction that was common in all the states: “Almost the sole topic of conversation among the colored people is the feat performed by the negro Frank Hart, and they seem quite proud of their champion.”

Finally, a particularly cruel reaction printed in the Agriculturalist in Kansas directed at black migrants from the South, “If this knack of walking is by any means peculiar to colored people, we suggest that those of the Exodusters who are too lazy to work and have to be supported by charity, pick up their heels and walk back where they came from.”

At the Top of the World

Hart went with O’Leary on a victory tour to various cities, putting on walking exhibitions. O’Leary praised Hart’s effect on others. “The colored boys are all crazy to walk, and darky pedestrians will probably soon be almost as numerous as blackberries in summer.” O’Leary also expressed some racist observations that were common for the era, saying, “One great difficulty has been encountered in handling this class of men, and that is their desire for sleep. It gives the white man a decided advantage. The moment that night comes on, a terrible drowsiness is experienced that they cannot shake off without making a very great effort. With all his great score, Hart had to have his sleep, no matter how close the race might be.”

Hart’s prized belts went on display in a storefront in Boston. He turned his attention to putting together a contest against England’s greatest champion, Charles Rowell. But the Brits were insistent that any such match be competed in England.

Serious Illness

Then tragedy struck. On about July 20, 1880, Hart became critically ill. Early on, a reporter visited him at his home at 26 North Anderson Street in Boston with a high fever. Hart said, “I feel much better today but my physician says I must keep quiet. Ice seems to be the only comfort that I have. My head worries me considerably, but I am satisfied that I will come out all right. It, however, annoys me, as I fear that it may hurt my chances for holding onto the O’Leary belt. But you can tell my friends that I hope to get out of my present sickness and show them that Boston’s representative will not be behindhand at the next race.”

After a few days, things got worse. “He spent a very restless night, and his family and friends are considerably exercised as the result. His trainer, Happy Jack Smith, arrived from New York and will watch him with his usual care. His presence seems to have given much confidence to the sick champion.” His doctors diagnosed, “congestion of the brain,” thought to have been caused by sunstroke. “Added to this, the great strain that he has endured by the loss of sleep in his tasks has been sufficient to affect his nervous system, which with excitement, has brought on the present fever.” The press also speculated that he had typhoid fever.

Adding to Hart’s tragedy, his two-year-old daughter, Sarah, died on July 30, 1880, of “tuberculous meningitis” while Hart was still very low. She had been sick for two weeks. Hart likely had the same disease.

News of his illness spread across the country. Some editors were cruel. In Buffalo, New York, “Frank Hart, the peacock of pedestrians, the dandy of darkies, is sick with congestion of the brain. It is odd that the disease did not attack him in the legs.” In Ottawa, Canada: “Frank Hart, the colored pedestrian, is dying in Boston. It is noticeable that men who force nature in any way, die young.”

Smith tried to nurse Hart back to health, giving him alcoholic baths. After a few days, Smith reported Hart’s condition. “I am glad to say Frank is much better tonight. He is more rational, but I do not yet consider him out of danger. I have followed the doctor’s orders to the letter and allowed no one to see him. I will spare no expense to see Frank on his feet again. We’ll take the starch out of those English blowers.” Daniel O’Leary kindly came from Chicago to visit him.

After about two weeks, Hart told a reporter, “I’m all right now, but I’ve had a siege of it.” Smith added, “Hart’s appetite is excellent, he sleeps well, and will soon be able to sit up. The crisis is past, he is all right now, and you can bet your bottom dollar that he will win another race.” Hart had lost eighteen pounds during his health scare. After three weeks of caring for him, Smith returned to New York City. Hart let Smith train fellow black pedestrian, Pegram, who was training for the 6th Astley Belt race.

After a month of being struck by the illness, Hart was finally getting outside, taking carriage rides. He said, “My appetite is poor, owing to the fact that my stomach is very sensitive. I am able to get around my house pretty well, but I am very cautious. I do not expect to be able to go into training until late this fall. I am going to act with caution, and follow my physician’s instruction, for I expect to have a few more trophies.” It would be impossible for him to try to bring the Astley Belt back to America in September 1880 and the next O’Leary Belt challenge was postponed for several months to let him recover.

In October 1880, Hart severed ties with his agent, Jacob Gottlob, and planned to sail with O’Leary and others for England to support the American runners competing in the 6th Astley Belt race. However, while in New York City, he lost another child. On October 14, 1880, his baby son, William Walter Hart, eight months old, died of cholera, back in Boston and was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery. Hart decided to return to Boston and start training to defend the O’Leary Belt.

World Record Broken by Rowell

On November 5, 1880, Charles Rowell of England won the Astley Belt again and broke Hart’s world record by one mile, reaching 566 miles. Losing the world record, especially to a Brit, was disappointing for Hart. Rowell won the belt by nearly 100 miles but went on to snag Hart’s world record “for the fun of it.” Hart publicly challenged Rowell to a six-day race in New York, saying, “I will put up dollar for dollar of his, and will beat him, and let him see that there is no fun in beating me.”

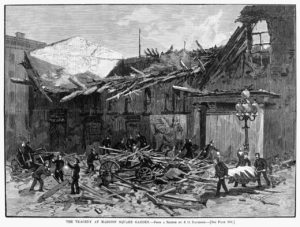

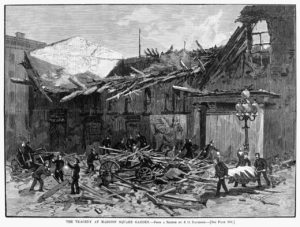

The next O’Leary Belt was planned to be held during Christmas week, but Madison Square Garden had been condemned because of an accident on April 21, 1880, when the walls fell, tragically killing four people, two horses, and wounding sixteen other people. During the Hahnemann Hospital Fair, the front of the building facing Madison Avenue gave way and fell outwards, causing part of the roof to fall inside the building. “The cause of the accident was the dancing, which shook the beams and strained the trusses, causing one or more of the latter to give way.” The builder of the building believed the roof gave way because of overheating of the timbers by gas.

Repairs had not been finished and the building could not yet be scheduled for December. But the American Institute Building (former Empire Skating Rink) was engaged for the race to be held in late January 1881, giving Hart another month of training.

The sporting world wondered if Hart would return to his previous dominance. “The impression in New York is that Hart is fearful of again entering in a long-distance match, or that having accumulated so much money he is not willing to again pound the sawdust.”

Word spread, “It looks as if the young man from Haiti was breaking up.” Was Hart washed up as an ultrarunner? “The general opinion among the pedestrian fancy is that Hart, the colored boy, has broken down. Hart should enter the (O’Leary Belt) race if only to prove to his friends that he is as game as ever and is not afraid to meet a number of good men.”

Sources:

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Oct 14-15, 23, Dec 17, 1879, Jan 3-4, 6, 28, Feb 5, Mar 10, Apr 7, 11-12, 24, Jul 25, 27, 28, Aug 6, 8, 22, Sep 26, Oct 3-4, 17, 21, Nov 8, Dec 19, 1880, Jan 9, 1881, Dec 19, 24, Nov 27, 1914

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Oct 11, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Dec 23-27, 1879, Mar 28, Apr 11, 1880

- The Sun (New York, New York), Dec 26 28, 1879, Apr 6-11, Dec 29, 1880

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Dec 29, 1879

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Dec 30, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Dec 23, 1879, Apr 9-12, 1880

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Apr 1, 1880

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Apr 5, 1880

- The Times-Picayune (Louisiana, New Orleans), Apr 12, 1880

- The South Bend Tribune (Indiana), Apr 12, 1880

- The Comet (Jackson, Mississippi), Apr 14, 1880

- Knoxville Whig and Chronicle (Tennessee), Apr 21, 1880

- The Greeley Tribune (Kansas), Apr 30, 1880

- The Western Spirit (Paola, Kansas), Apr 30, 1880

- Evening Mail (London, England), Apr 28, 1880

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Jul 27, Aug 18, 1880

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Jul 30, 1880

- The Ottawa Free Trader (Canada), Aug 14, 1880

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Aug 20-21, 1933