Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:30 — 35.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

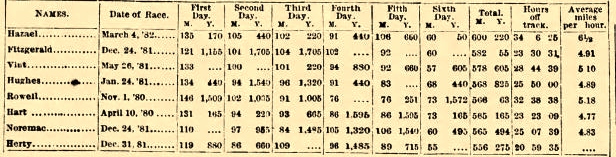

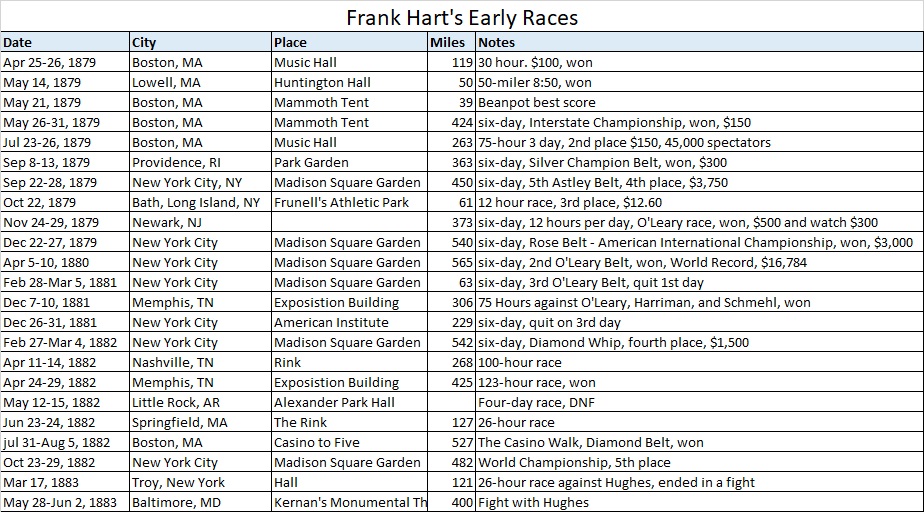

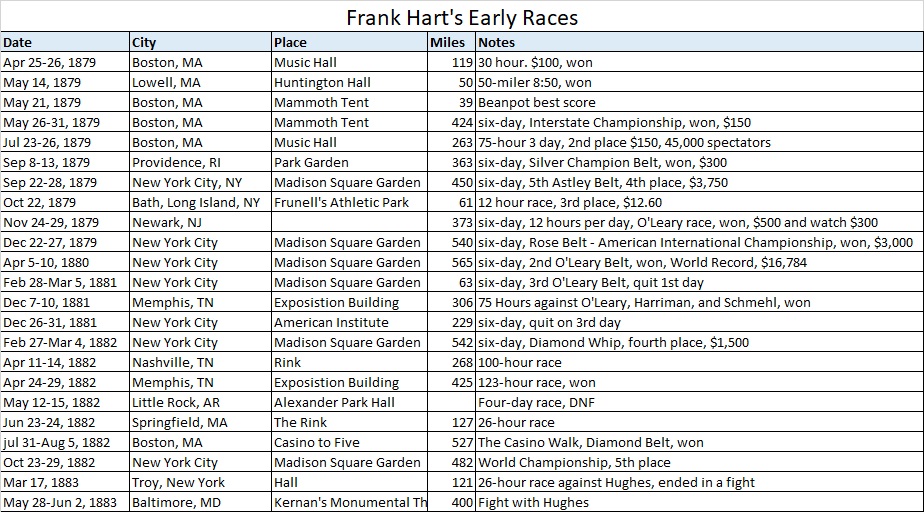

Hart’s six-day world record of 565 miles had been broken by Charles Rowell (1852-1909) of England by one mile in November 1880, which deeply bothered Hart. In January 1881, he accepted a challenge from Rowell to meet head-to-head later in the year. That became his focus and he tried to get back into world championship shape. But then another rival appeared on the scene full of racist hatred.

Racism from a Competitor

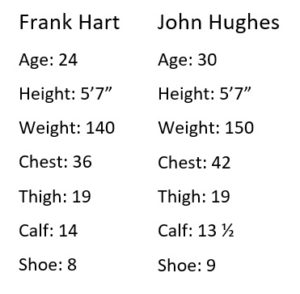

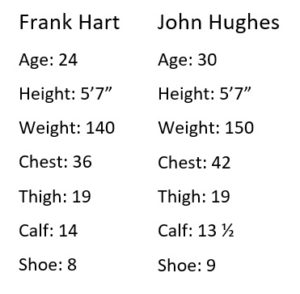

John “Lepper” Hughes (1850-1921) of New York did not hide his racist hatred for Hart. He had been a “poor day laborer” before he found success in pedestrianism. He was born in Roscrea, Tipperary, Ireland, and was the son of a competitive runner. When he was a boy, he was a fast runner, won some races, and could run close to hounds in fox hunts. With no formal education, he emigrated to America in 1868 at eighteen, became a citizen, and worked for the city of New York in Central Park. It was said that he was “stubborn as a government mule.” He was called, “the Lepper” because of his peculiar way of walking with an odd jumping gait.

Hughes was known for his temper and often showed inappropriate behavior in races. He desperately wanted to be recognized as the champion pedestrian of the world. It was reported, “Hughes is a boastful and ignorant fellow, with a fine physique and unlimited confidence in his powers.” He had a deep personal hostility against fellow Irish American, Daniel O’Leary, who had beaten him soundly in the Second Astley Belt Race in 1878. Hughes blamed his backers for purposely poisoning his milk and swindling him out of all his prize money.

Since then, Hughes had experienced some success but had failed to win any of the big six-day races. His best six-day mark was 520 miles, when he finished sixth at the Rose Belt Race in 1879, won by Hart.

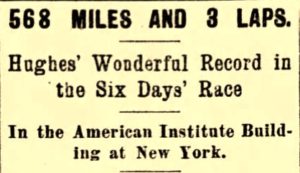

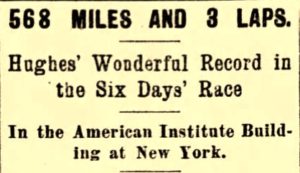

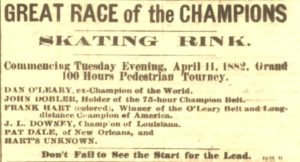

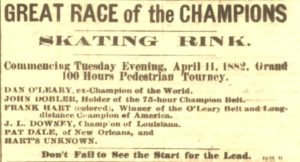

But finally, on January 29, 1881, Hughes had the finest race of his career when he broke the six-day world record, achieving 568 miles in the “First O’Leary International Belt Race” held at the American Institute Building in New York City. Hart did not compete in the race, choosing instead to get ready to defend the original “American” O’Leary Belt, to be held the following month. As the Third O’Leary Belt approached, Hughes desperately wanted to win that O’Leary belt too and beat Hart. He boasted he would cover 600 miles.

Hart and Hughes Fight

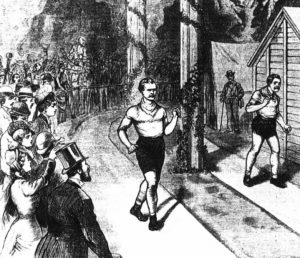

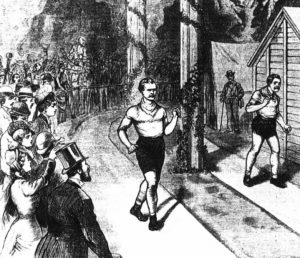

In 1881, Bernard Wood’s Gymnasium and Athletic Grounds on North 9th and 2nd Street (Wythe Ave) in Brooklyn, New York, was a popular place for runners to train on an indoor sawdust track. In February 1881, both Hart and Hughes used the track to train for the upcoming O’Leary Belt. Hughes would often yell hate-filled racist slurs at Hart. Hart had nothing good to say about Hughes.

One Sunday afternoon, while both were training there, they competed in an ego-based sprint together, which Hughes won. Hart joked that at the upcoming match there would be no poison soup, referring to Hughes’ excuse for losing the Second Astley Belt. He added he would beat Hughes at the upcoming match.

“Hughes turned around and shouted, ‘You lie, you black (n-word).’ Saying this, he struck Hart with a powerful blow under the chin. Hart fell flat on his back but was up again in an instant and hit Hughes over the right eye.” They continued to deliver blows, but Hart was no match for the bigger Hughes. Trainer Happy Jack Smith jumped in and separated them. “As Hart went away, Hughes shouted at him, ‘I’ll kill you the next time I meet you on the track.” Hughes had a black eye, and Hart had a swollen cheek.

When a reporter asked Hughes why Hart didn’t have a black eye, he replied disgustingly, “I would have had to put white marks on Hart to have given him black eyes, wouldn’t I?” Hughes moved his training to the American Institute Building. His wife said, “He does not wish to associate any longer with such low trash as frequent the Williamsburg (Brooklyn) Gymnasium.”

Third O’Leary Belt

Hart was determined to stay ahead of Hughes. “Happy Jack Smith, his handler, who wears a fine diamond scarf pin, said that Hart, for the first time in his racing career, refused to obey his instructions. He traveled altogether too fast in the first two hours of the race, keeping it up after repeated cautions to slow down. Jack ran around an entire lap with him to his endeavors to put on the brakes.” Several “loafers,” hung over the rails, subjecting Hart to terrible racial insults, such as “You ought to be jerked from the track with a rope around your neck.”

Unfortunately, Hart withdrew from the race due to nerve pain after running only 63 miles. The doctor reported, “He is suffering from intercostal neuralgia caused by taking cold during the walk wearing too light clothing.” The explanation did not satisfy bookmakers, who believed he quit to save himself to compete against Rowell, who had come from England. Smith said, “The truth of the matter is, Hart tried to kill Hughes with the pace and succeeded in killing himself.” Others speculated his downfall was from his mode of living since he became rich and from his severe sickness the previous year.

Hughes was elated that Hart dropped out. He took the lead and reached 100 miles in 16:20, but he soon lost the lead when he went off track to take an alcohol bath. When he returned, he was stiff. “The change in Hughes’ demeanor was marked. His stolid face had almost become a bright one when he learned of Hart’s withdrawal, but now he scowled blackly at the new leader, and all the spirit seemed to have gone out of him. He couldn’t or wouldn’t run.”

Hughes made frequent brief stops on day two and experienced “excruciating pains in his stomach,” causing him to fall on the track. He eventually got up, but continued to complain loudly. “His face became pale and his whole body swayed to and fro like an intoxicated man.” He finally quit the race after only 115 miles. “It was agreed that Hart and Hughes had allowed their personal animosity, by inciting them to an exhaustive struggle at the outset, to defeat them both. Both cried like babies and cursed their trainers, while their trainers as heartily cursed them back.” Hart’s public image took a tremendous hit, and criticism filled the newspapers. On his return to Boston, he said that he cared nothing for newspaper opinions.

To England

Hart sent in his deposit for the Seventh Astley Belt Race to be held in England during June 1881, hoping finally to race against Rowell. He promised his friends that he would train hard and make a good account for himself in the next race. On April 17, 1881, he sailed for England on the steamer Canada to get ready for the June race. His new manager, John W. Luke, a former private detective from New York City, went with him, along with one of Hart’s black friends who would serve as his attendant. Night and day, he trained running or walking on the deck of the steamer.

Happy Jack Smith did not accompany them. He had resigned as Hart’s trainer because Hart would no longer train as Smith desired. After all that Smith had done for Hart, including nursing him back to health, their breakup was sad to see. He said Hart’s downfall was from “cruising around town at nights when he ought to have been in bed.” Even during six-day races (12 hours per day), he would sneak out of his hotel without being seen by his trainer, dressed in “frills and fancy jersey” and party late into the night with friends. Smith took on the role of trainer for John Dobler, as people viewed him as the best trainer in the sport.

Hart arrived in England on May 1, 1881. He trained with Blower Brown, at Turnham Green, a public park in a suburb of London. As the race approached in June, probably because of over-training, his feet swelled, and his legs suffered from rheumatism. Unfortunately, he had to pull out of the Astley Belt race. He was bitterly disappointed. London sports reported, “Frank Hart, who came over here with the express intention of whipping all wobbling creation has gone in for rheumatism instead.”

Hart went to Nice, France, to get better. “He dabbled in horse racing and lost $10,000 on the turf in England and $5,000 in Paris. His trip cost him $17,000 (valued at $500,000 today, more than half of his fortune), and as he remarked resignedly, ‘It has cost many a man more.'”

Hart Arrested in England

They caught Hart, but his friend escaped. A couple of weeks later, the Grand Jury threw out the case. The London Age reported, “The charge against Hart was utterly devoid of foundation and the grand jury, without hesitation, threw out the bill. Hart, leaving the court without a stain on his character.” Unfortunately, this outcome was not printed in papers across America.

Hart Attempts Comeback

The Diamond Whip Six-day Race

The referee said he could enter anyway with agreement from all other entrants; however, they were not unanimous in letting him in without paying. He finally raised the $1,000, with Rowell kindly contributing $100, but it was past the deadline. Again, some of the other entrants, including his nemesis Hughes, opposed his late entry. “Hughes positively refused to hear of Hart’s admission on any terms.” Hart was greatly disappointed, and his new backers tried hard to change Hughes’ mind, but he refused. Hughes claimed Hart owed him $100 and believed that if Hart was in the race, he would focus on preventing Hughes from winning, by dogging his steps.

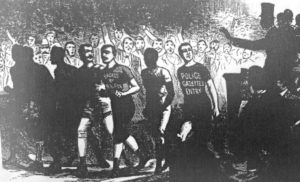

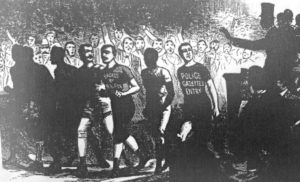

It amazed everybody when Hart entered the Garden and went towards one of the runners’ cabins an hour before the start of the race. The scorer at the great blackboard put up Hart’s name. Reporters were informed that Hughes had finally consented to let Hart run. “The fact soon became known to the vast throng, and the cheers showed how great was the sympathy with Boston’s colored athlete. Hart himself was overjoyed and was so moved that he could hardly speak.” It turns out that the notorious police Captain Alexander “Clubber” Williams (1839-1917) convinced Hughes to let Hart in – likely a little blackmail to pay off a shady favor Williams had previously performed for Hughes.

At the start line, something surprising occurred. “Hart was chewing a toothpick, and as he turned, he saw Hughes. Stepping up to the latter, he grasped his hand and vigorously shook it.” Early in the race, Hart ran alongside Rowell, angering some in the crowd who speculated that Hart had been allowed to run to help Rowell. By running next to Rowell, he could also block other runners from passing. Hughes complained to the referee and wanted Hart to be kicked out of the race. The crowd “hissed” Hughes. Finally, some in the crowd screamed, “Clear the track, Hart,” and he ran ahead. After Hart bumped Hughes while passing him, Hughes shouted to the referee, “I rule this man out.” Hart gave his side of the story to the referee and was allowed to continue. Whenever Hughes ran near Hart, a scowl would appear on his face.

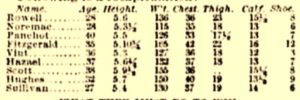

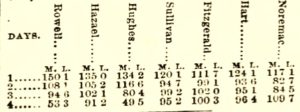

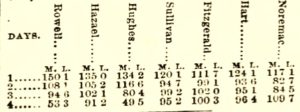

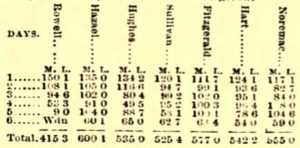

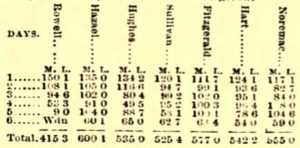

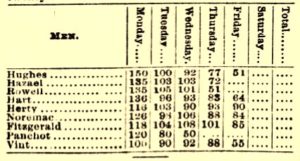

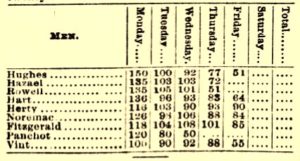

On the first day, Rowell covered an astonishing 150 miles. Hart was in third place with 124 miles. Unfortunately, during the night, a cold settled in his chest and slowed him down the next morning. Gottlob, Hart’s re-hired manager, said that Hart began the race at the last minute with hardly any provisions, two bottles of ginger ale, and a bottle of cold soup and that his cabin was poor. But Hart continued and reached 217 miles after day two, 313 miles after day three, and 409 after day four, accomplishing the extremely rare 400+ miles in four days for the second time in his career.

Hughes broke down on day four, went at a “snail-like pace with an agonized countenance, a sorry figure on the track” and fell in the standings but recovered the next day. His remaining focus was to just beat Hart, and the spectators cheered him on in his effort.

On the last day, Hughes kept gaining on Hart. During the final laps of the race, Hart, in one of his many colorful outfits, came up to pass Hughes, and he put out his hand for Hart to grasp. “The two bitter enemies were thus reconciled. Both raced like mad the length of a lap, and the crowd strained its lungs with shouting.” But in the end, Hart prevailed and for the first time in nearly two years, he finished a six-day race. He placed fourth and reached 542 miles to Hughes’ 535 miles.

The big story of the race was that George Hazael (1845-1911) of England became the first person in history to reach 600 miles in six days, crushing the world record and winning the diamond-studded whip. Hart won a much-needed, $1,500 (valued at $43,000 today) to maintain his lifestyle and pay off debts.

Hart Sued by Former Manager

At the end of the race, the referee was presented with a legal summons against Hart’s winnings. His former trainer, John W. Luke, was suing Hart for $313.75, for lack of payment of services at the failed effort in England. Hart got wind of it and made his escape. “He put on a big overcoat and a high hat, fixed a huge cigar in his mouth, broke a hole in the roof of his quarters, climbed through, leaped ten feet to the ground, and got out the back door. There, a carriage awaited him and one of his backers thrust him into it, whispered to the driver, and saw him safely away.” He hid and reportedly was evading deputy sheriffs. Gottlob took control of Hart’s winnings, but could only get $1,000 from race management who held back $500 to satisfy Luke’s claim. Hart’s reputation in Boston took another blow.

Hart Leaves Boston with Financial Difficulties

At the end of March 1882, The Boston Globe reported, “Frank Hart has left Boston for good. He says he hasn’t a friend in the city, either white or colored.” Hart was being pursued by other debtors. The Sheriff seized some of Hart’s land and buildings in Boston on Blossom Street and put up for auction to cover his foreclosed mortgage. (The Wyndham Boston Beacon Hill Hotel stands there today). His wife still lived on some property a block to the west on North Anderson Street.

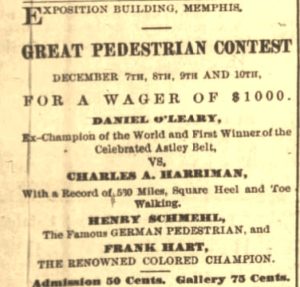

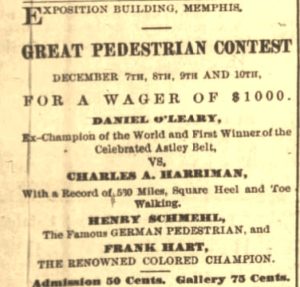

Hart went on a southern barnstorming tour to Tennessee and Arkansas, with O’Leary and others, where he competed in leisurely races and exhibitions, more for money, less for competition. He was pleased to be away from controversy and treated like a celebrity again. In June 1882, with money back in his pocket, Hart returned to Boston, entertained at The Casino, raced on foot against cyclists in handicapped races, and made other circus-like appearances at carnivals.

Casino Police Gazette Diamond Belt Six-Day Race

At the end of July 1882, Hart competed in a serious six-day race with several of the famous pedestrians of the time, including his nemesis, Hughes. The race was held in the massive Casino Building in Back Bay, Boston. “The crowd was very small, and in the immense building looked even less than it really was. Hughes made fifty miles and then drew out in disgust. He gave as his reason that the track was not good, being soft in places.” But the real reason likely was because Hughes had not been training much, showed up with “considerable surplus flesh,” and clearly did not like running with Hart.

Championship of the World Six-day Race

The next major race was the “Championship of the World” six-day race at Madison Square Garden on October 23, 1882. Hart wisely kept a low profile and seemed to concentrate on serious training. He had reunited with world-class trainer, Happy Jack Smith. Hart said, “Happy Jack Smith, and I have buried the hatchet, and I am confident of breaking all past records.” Smith was very pleased with Hart’s conditioning going into the race. Hart re-embraced Boston and said that he was representing the city and would bring back the colors to the “Hub.”

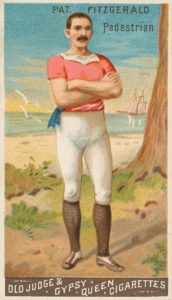

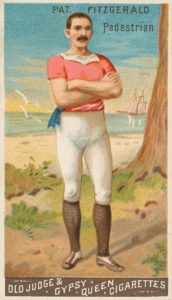

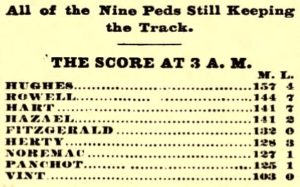

When the nine runners came to the start line, Hart looked the most impressive in his red drawers, gray trunks, white shirt, and fancy jockey cap. Hughes was in the race and swore to run “the n-word” down on the first day. After the start, the two went out hot and finished the first mile in 6:16. It was observed, “Hart is the prettiest ped on the track. His gait and the earnestness with which he jogs along are inspiring much confidence in his being, perhaps, the dark horse.”

Hughes took the lead and was the first to reach 100 miles in a very speedy 14 hours. (The world record stood at 13:26:30, set by Charles Rowell at the Diamond Whip race earlier in the year). Hart ran well, but there still was some drama involving him. While Smith was sleeping, Hart drank champagne, something Smith did not want him to do.

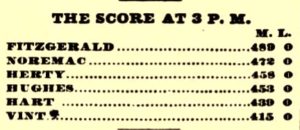

On day four, Smith was frustrated with Hart, who was still 30 miles behind the leader Fitzgerald. He said, “He is lazy. You can’t depend on him at all. If a man won’t do as you tell him to, he puts you in a hole. When we give Frank beef tea, he spurts it on the track. He wants nothing but slops all the time. I never saw him so before. He’s playing possum with you all the time.” In protest, Smith temporarily quit as Hart’s handler during the afternoon. Hart worked harder and surpassed 400 miles in four days, as did four others. It truly was a world-class race, although the world record holder, Hazael dropped out with 383 miles.

On the morning of day five, Hart fell on the floor of his room with terrible cramps. Smith, who had returned, worked on him, and he soon recovered. Then Hart apologized to Smith for the way he treated him the previous day and promised to follow his advice for the rest of the race. He pulled ahead of Hughes and reached 476 miles at the end of the day.

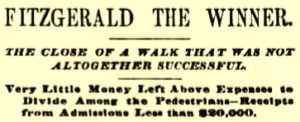

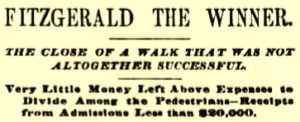

On the final morning, Hart sat in a chair with a badly swollen knee. He said, “I have honestly done my best, although everyone has called me lazy. But the truth is the atmosphere (smoke) of the Garden would kill anyone. Here I am now, as you see me, played out.” He tried to continue but withdrew at 10 a.m. with 482 miles. In the end, Patrick Fitzgerald from Long Island won with 577 miles. Smith again stopped training Hart and eventually moved on to train Fitzgerald.

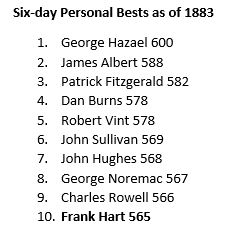

Boston considered Hart’s effort a failure. There were some rumors that Hart had been bribed to quit, but he vigorously denied that. It was reported, “The next six-day race will be his last, when he hopes to return to Boston, having reclaimed his lost laurels.” Would he really retire? No, it was a proven source of enormous income for him. But Hart just wasn’t keeping up with the competition. Since Hart set the six-day world record of 565 miles in 1880, nine others had surpassed his mark during the next four years. He was now ranked tenth in the world.

Hughes vs Hart Fiasco

Early in 1883, again desperate for money, Hart issued Hughes a challenge to race for 26 hours, and Hughes accepted. A promoter took up the event and scheduled it for March 1883 in a minor venue in Troy, New York, across the Hudson River from Albany. They held female pedestrian events in that industrial city a few years earlier. They should have realized that this was a terrible idea to get the two hated rivals together. Throughout the race, the two had confrontations and were said to be in “a quarrelsome mood.”

Late into the race, Hughes was partaking a bit too much of stimulating booze. He had a good lead, 142 miles to 121 miles, but then he went crazy. He accused his backers of cheating him. He yelled, “You sold me out before, and you have done it again. The (n-word) has been sleeping, but his score was going up all the time while I was doing honest work.” Hart responded by punching him in the face and a “lively fight occurred for a few minutes until the crowd separated them.” The police came and found Hughes bleeding from his nose. They cleared the hall and put an end to the match. Hughes only earned $3.05 from the match. They caught Gilbert attempting to skip out of town without paying the bills. He lost $200.

Another Fight in Baltimore

Hughes, who was leading the race on day four with 410 miles, accused Hart of conspiring with George Noremac (1852-1922) to try to run Hughes off the track. Hart denied it and called Hughes names. Hughes struck Hart, pounding him in the face and throwing him over the rail, and “a lively tussle” continued. “Mrs. Hughes, who has been a faithful attendant on her husband, interfered to separate the men. Hart tried to bite her, but only succeeded in biting the sleeve of her dress. The combatants were parted.” The police stopped the fight. Hart treated his black eye, changed his ripped shirt, and continued, but only reached 400 miles, not enough to be eligible for any winnings. Hughes went on to win with 558 miles.

Sources:

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Apr 24, 1878

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jan 31, Feb 23, Mar 3, Jun 5, Jul 5, 10, Aug 10, Dec 30, 1881, Jan 22, Feb 19, 24, 26-28, Mar 1-5, 26, Apr 22, Jun 25, Aug 1-6, 13, Oct 4, 23, 28, 1882

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Jan 10, Apr 21, 1881, Feb 18, 1882

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Feb 21, Jun 4, 1881, Jun 1, 1883

- The Sun (New York, New York), Feb 22-23, 28, Mar 1, Dec 26, 28, 1881, Mar 5, Oct 27-28, 1882, Mar 18, 1883

- New York Tribune (New York), Feb 28, Mar 1, 1881

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Apr 19, 1881

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), May 9, 1881

- The Weekly Dispatch (London, England), Jun 12, 1881

- Edinburgh Evening News (Scotland), Jun 6, 1881

- San Francisco Chronicle (California), Jun 16, 1881, Feb 14, 1889

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Oct 3, 1881

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Nov 27, 1881, Mar 19, 1883

- The Daily Memphis Avalanche (Tennessee), Dec 8, 1881

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Dec 29, 1881

- The New York Times (New York), Dec 29, 1881, Feb 27, Mar 9, 1882

- Kansas City Times (Missouri), Feb 16, 1882

- The Times Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Mar 10, 1882

- The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), Apr 11, 1882

- Boston Evening Transcript (Massachusetts), Jun 15, 1882

- The Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), Jun 26, Dec 4, 1882

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Aug 1, Oct 3, 1882

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Oct 23, 1882

- The Critic (Washington D.C.), Jun 1, 1883