Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:04 — 22.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

50 years ago, on August 3-4, 1974, Gordy Ainsleigh accomplished his legendary run on the Western States Trail in the California Sierra. It became the most famous run in modern ultrarunning history. Initially, it went unnoticed in the sport until several years later, when, with some genius marketing, it became the icon for running 100 miles in the mountains, the symbol for Western States 100, founded in 1977 by Wendell Robie. With Ainsleigh as the icon, Western States inspired thousands to also try running 100 miles in the mountains on trails. Let’s celebrate this historic run’s 50th anniversary.

History Note: You were probably told Ainsleigh was the first to do this, but he was actually the 8th to cover the Western States Trail on foot during the Tevis Cup horse ride. Others were awarded the “first finishers on foot trophy” two years earlier, in 1972. Also, the sport of trail ultrarunning was not invented in 1974. It had existed for more than 100 years. There were at least eight trail ultras held worldwide in 1974, including a trail 100-miler in England. Previous to 1974, more than 1,200 people had run 100 miles in under 24 hours in races on roads, tracks, and trails, including some women.

| Learn about the rich and long history of the 100-miler. There are now three books that cover this history through 1979. Learn More |

The Early Years

Frank Ainsleigh left the home, quickly remarried, and eventually settled in Florida where he raced stock cars and worked in a Sheriff’s office as maintenance supervisor over patrol cars. Bertha Ainsleigh remarried in 1952, when Gordy was five, to Walter Scheffel of Weimar, California. He was employed at a sanatorium. But Gordy’s family life continued to be in an uproar. They divorced less than a year later.

Gordy Ainsleigh spent his childhood years in Nevada City, California, about 30 miles north of Auburn. (This is the same town that seven decades earlier put on a 27-hour race in December 1882, won by Charles Harriman (1853-1919) with 117 miles.) Ainsleigh recalled his first long run as a child. “One day when I was in second grade. I came out on the playground with a bag lunch that Grandma had packed for me, and I just couldn’t see anybody who would have lunch with me. I panicked. And I just felt like I couldn’t breathe. And I just dropped my lunch, and I ran home for lunch.” On another day, he missed the bus for school and didn’t want to admit to his mother that he again missed it, so he just ran several miles to the school. He explained, “I came in a little late. The teacher knew where I lived. She asked, ‘Why are you late?” I said, ‘I missed the bus, so I ran to school.” She was so impressed that she didn’t punish him.

By the age of fourteen, Ainsleigh started to get into trouble with the law, so his mother decided it was time to move out of town, back to the country. They moved back closer to Auburn, to a small farm near the hilly rural community of Meadow Vista. In junior high school, his gym teacher treated P.E. like a military boot camp with lots of pushups. He recalled, “I’d goof off and he’d make me run. I made sure I wore a real pained expression whenever he could see me. Actually, I was having a good time.” Living on a farm, he grew up among livestock animals, and in 1964 was given an award at a country fair for a sheep.

High School, College, and the Military

But perhaps Ainsleigh’s greatest recognition in college was winning the 1967 Sierra College Pancake Tournament. “He consumed 30 pancakes, breaking his record of 24 ½ at the beginning of the competition. Ainsleigh took advantage of all the rules which allowed anything inside the mouth to be counted as consumed while pancakes still outside were disallowed.”

In 1968, Ainsleigh served in the military and did his basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. While there, he was given an award for the highest rifle score in his company. In July 1968, he volunteered for a 21-day high altitude testing program conducted at Fort Sam Houston in Texas and at Pike’s Peak in Colorado. He took part in a series of diet and exercise tests as part of the program.

In 1969, Ainsleigh was back in California, and started to attend the University of California, Santa Barbara. He wasn’t fast enough to qualify for their cross-country team.

In 1970, he was caught up in violent anti-war and anti-apartheid unrest and rioting taking place near the UC Santa Barbara that had been going on for months. In June, police conducted raids to quell student unrest taking place during a dawn to dusk curfew. Ainsleigh was there, taking part in a sit-in at a local park. He was part of a group of 200 who were ordered to disperse but did not, and then were sprayed with pepper gas. Ainsleigh claimed he had been hit by police on the skull four times and said, “I didn’t really believe one person would hit another person who wasn’t threatening him. I kept thinking that after this one, they’ll quit. I thought they wouldn’t keep beating a person on the ground, but they did.”

Endurance Riding

In 1971, at age 23, while going to UC Santa Barbara, Ainsleigh bought a horse named Rebel. One day he read a notice on a bulletin board about an endurance horse race, the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup) which was held just miles from his home. He had never heard about it before, but wanted to give it a try. It was a 100-mile horse race (actually less the 89 miles) from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California.

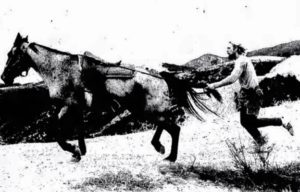

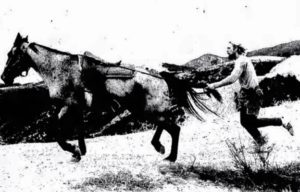

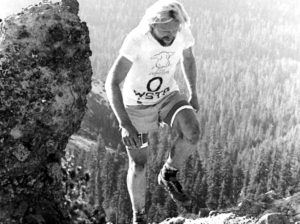

Ainsleigh entered and rode on his eight-year-old horse, Rebel. Staggered starts were used with small groups of riders starting together. There were four key checkpoints in place that year with mandatory rest periods. Ainsleigh, disadvantaged because of his larger frame and weight, had to run many miles ahead or behind his horse to take the weight off and make faster progress. He finished in great pain at the fairground’s stadium in Auburn, with a time of 19:37. Ainsleigh said that after that 1971 ride, he began to consider running the entire Western States Trail, but it took several more years to take place.

The First Finishers of Western States Trail on Foot

Ainsleigh Runs Ultra Distance

Ainsleigh dropped out of college and worked in logging/tree-removal. He didn’t know what he wanted to do in life and felt depressed. He visited his old high school and started running long distance road races with the school’s math and music teacher. He also started to run on trails.

Several ultras were held in the San Francisco and Sacramento area since 1970, involving about 100 California ultrarunners, but Ainsleigh had not heard about them. (In 1971, Jose Cortez (1951-) broke the American 100-mile record with 12:54:31, at the Camellia 100, held just 13 miles from Auburn, in Rocklin, California).

In 1973, Ainsleigh went to another endurance ride event, 50-miler, to attempt to run it on a $10 bet. It was the Castle Rock 50 Mile Ride, in Big Basin Redwood State Park, southeast of San Jose, California. This race was established in 1967, patterned after the Western States Trail Ride. Ainsleigh successfully ran the 50-mile course in about nine hours, finishing in the middle of the pack of riders who had two mandatory one-hour stops. That year, Ainsleigh also finished a marathon in a very impressive time of 2:57:07, weighing more than 200 pounds.

1973 Western States Trail Ride DNF

On July 14, 1973, Ainsleigh rode the Western States Trail Ride for the third year but only made it to Robinson Flat (mile 30), which took him seven hours. His horse, “Old Rattle Nose” was lame and couldn’t continue, so he dropped out of the race. He never replaced that horse and thus didn’t have one for the next year’s race.

Ride and Tie Success

Ainsleigh’s Historic 1974 Run

A few weeks later, with that success at the Ride & Tie, Ainsleigh became confident that he could run Western States without a horse. He had intended to ride it again, but had given away the horse he used the year before and had procrastinated finding another horse. Dru Barner (1914-1979) Wendell Robie’s assistant, suggested and encouraged Ainsleigh to run the course on foot. She said to him, “We’re all wondering when you’re going to leave the horse behind and just do it on foot.” Indeed, he wanted to try cover the trail much faster than the soldiers did two years earlier and beat the 24-hour cut-off time established for the riders and horses. Many, including Robie, were skeptical if he could pull it off. He said, “It is probably a universal opinion that it is beyond the powers of human endurance to span the 100 miles of this rough mountainous trail on foot in a period of 24 hours, but Harry (Gordy) probably will make one or two of the control stations within the operational schedule.”

To train, Ainsleigh would get a car ride to Michigan Bluff and then run to Auburn. He did that four times in six weeks. In preparation, a few days before the race, he rode his dirt bike to various points on the course and dropped off Gatorade that he would need during the run.

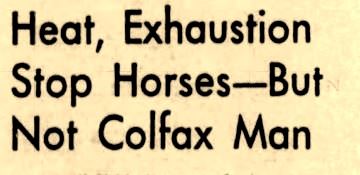

The horses then started to pass him as he slowed, but he passed them again as they slowed and took their mandatory rest stops. A kind timing crew gave him canned peaches at Last Chance and at Devil’s Thumb he was really struggling in the 107 degree heat. He had decided to quit because he was so drained and felt so weak. His sister was stopped there with a lame horse and recognized that he was dehydrated and suffering from hyponatremia. She revived him with salt and water. Thirty minutes later, he was on his way again.

From Michigan Bluff to the finish, he “panhandled” for food and liquids from plenty of people on the course. He stopped at one point to help some riders with a horse that had collapsed in the river. With 20 miles to go, he asked for a guide rider in the dark to help pace him to the finish. Many people were curious and betting on whether he could finish by 24 hours. As the finish came closer, he had been passed by the majority of the horses and was running amidst the riders and horses struggling to make the 24-hour cutoff in time.

Ainsleigh entered the stadium before dawn on August 4, 1974, did a somersault before the finish line, and crossed with a time of 23:42. There were lots of cheers and congratulations.

It wasn’t until 2020 that Ainsleigh admitted on social media that the soldiers were indeed the first to cover the course on foot during the Tevis Cup. However, he disparaged the attempt. “When Wendell announced at the pre-ride meeting on Friday in 1972 that a crack marching team from Fr Riley KS had started out that morning, and were planning to finish before 5 on Sunday morning, I said to myself, ‘What? Anyone can do that!’ . . . The commanding officer should have been court-martialed for sending out untrained soldiers into such a stupid task.”

Western States 100 established, along with exaggerated claims

In the next couple years, others would try to run the course too, but it wasn’t until 1977 that Robie, President of the Western States Trail Foundation, finally decided to organize the Western States Endurance Run. Ainsleigh was not the founder of the Western States Endurance Run, Robie was. Ainsleigh did work hard for the 1977 race that came under the direction of Mo Sproul (Livermore) (1951-). But as planning occurred for the 1978 race, Ainsleigh was disappointed that he was not appointed as an officer on the first board of governors for the race (the gang of four). He was involved, but was relegated to a marketing role, to be brought out once a year to tell his tale and promote the race.

The Western States 100 Started in 1977

For 1977 and 1978, the marketing effort for Western States came together. The board strategically, according to one of their members, decided to “prop up” Ainsleigh’s story of his run and make him into the icon of the emerging race.

Ainsleigh did love the attention, and he was skillful and dynamic in his role. The board decided to bury the 1972 story of the soldiers, “kept under wraps” according to one member. Ainsleigh was proclaimed in marketing material and news stories as the first to cover the 100-mile course on foot.

The Western State origin story continued to be enhanced by Ainsleigh and the 1978 race organizers, who made some over-reaching historic claims. These people were primarily horse endurance riders, and were just becoming ultrarunners. They were focused on California, knew nothing about the history of ultrarunning and what was going on with 100-milers across the world. They did not know that more than 1,200 athletes had already covered 100 miles on foot in less than 24 hours on tracks, roads, and trails before Ainsleigh’s run. Historic accuracy was not their focus, marketing was.

The 1978 Western States Board of Governors thought their race was the first 100-miler and started to make that inaccurate claim. The focus for Robie and these organizers was to make Auburn California “the endurance capital of the world.” Despite their over-reaching claims, their efforts were amazing and would bring Western States 100 into the world spotlight. Dozens of 100-milers would pattern their races after Western States.

The 100-mile ultrarunning history claims would continue to grow through the years. Ainsleigh, who was a mid-pack runner, was proclaimed by some as being “the godfather of the sport,” ignoring the true modern-era contributions by Ted Corbitt in New York, who brought ultrarunning back to America in 1959 (after going away during the depression and war years), and awarding the first ultra belt buckle in 1959.

Ainsleigh was also called “the man who invented trail ultrarunning” a claim that Ainsleigh embraced on his personal website and on podcasts for many years. Trail ultrarunning, including races, had existed for decades before Ainsleigh was born. Ainsleigh and Western States marketers just did not know about ultrarunning history. They were endurance riders.

Despite the inaccurate claims, Ainsleigh went on to be an important ambassador for the sport of ultrarunning. To his credit, he was the man who put the greatest spotlight on trail ultrarunning as it was evolving in the 1980s. Happy 50th year anniversary of the run. (As of 2024, the Western States Endurance Run has been held for 46 years).

Sources:

-

- Auburn Journal (California), May 8, 1947, Sep 18, 1952, Sep 17, Dec 15, 1964, Jul 31, Aug 23, 1974

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Nov 20, 1965, Mar 10, 22, 1975

- The Placer Herald (Rocklin, California), Nov 23, 1966, Jun 20, 1989

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, California), May 19, 1967, Jul 15, Aug 6, 1974

- The Tampa Times (Tampa, Florida), Apr 26, Jul 26, 1968

- Arizona Republic, (Phoenix, Arizona), Jun 12, 1970

- The Times (Nanaimo, Canada), May 25, Oct 1, 1974

- The Province (Vancouver, Canada), Apr 23, 1973, Oct 1, 1974

- The Ottawa Citizen (Canada), May 27, 1974

- The Leader-Post (Regina, Canada), May 28, 1974

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Dec 5, 1975

- Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida), May 10, 1075

- Ashbury Park Press (New Jersey), Jun 7, 1975

- The Orlando Sentinel (Florida), May 29, Aug 10, Nov 25, Dec 2, 1975, May 11, 27, Jun 4, 1976

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Jan 12, 1997, Dec 24, 2015

- Social Media conversations on Facebook in 2020, 2022

- gordonainsleigh.com

- Gordon Ainsleigh, the first trail ultra

- A Horse Race Without A Horse: How Modern Trail Ultramarathoning Was Invented

- NorCal Running Review No 46.