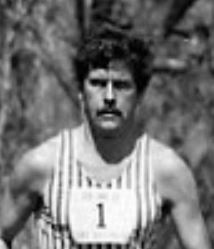

Park Barner is the first Ultra Hall of Fame inductee who could legitimately be called a “legend in his own time.” In the late 1970’s he was the first American ultrarunner to become broadly known for his ultra exploits outside the ultrarunning community. In today’s age of celebrity ultrarunners who make the rounds on national TV talk and entertainment shows, it is worth noting that Barner received an invitation to appear on The Tonight Show, hosted by the late Johnny Carson, 33 years ago (he turned it down because he preferred to save all of his vacation days for traveling to ultras). And this unique stature–remarkable so early in the sport’s history–was certainly not achieved by self-promotion. Barner, from a small Central Pennsylvania town, was shy, disarmingly humble, a man of few words. He was not a talented athlete (his fastest mile was 5:19), and he had an unusual, multi-faceted athletic career. He almost never became an ultrarunner because he almost became a professional bowler. To celebrate his 39th birthday he bowled 39 straight games, averaging 199. Much later, in his 60’s, after retirement from serious bowling and serious ultrarunning, he became a serious practitioner of the art of pitching horseshoes. At the age of 63 he pitched 1,000 ringers in 8 hours. One might detect in this introverted, obsessive personality the key ingredients of a successful ultrarunner–and one would be right.

Park Barner is the first Ultra Hall of Fame inductee who could legitimately be called a “legend in his own time.” In the late 1970’s he was the first American ultrarunner to become broadly known for his ultra exploits outside the ultrarunning community. In today’s age of celebrity ultrarunners who make the rounds on national TV talk and entertainment shows, it is worth noting that Barner received an invitation to appear on The Tonight Show, hosted by the late Johnny Carson, 33 years ago (he turned it down because he preferred to save all of his vacation days for traveling to ultras). And this unique stature–remarkable so early in the sport’s history–was certainly not achieved by self-promotion. Barner, from a small Central Pennsylvania town, was shy, disarmingly humble, a man of few words. He was not a talented athlete (his fastest mile was 5:19), and he had an unusual, multi-faceted athletic career. He almost never became an ultrarunner because he almost became a professional bowler. To celebrate his 39th birthday he bowled 39 straight games, averaging 199. Much later, in his 60’s, after retirement from serious bowling and serious ultrarunning, he became a serious practitioner of the art of pitching horseshoes. At the age of 63 he pitched 1,000 ringers in 8 hours. One might detect in this introverted, obsessive personality the key ingredients of a successful ultrarunner–and one would be right.

Barner began his ultramarathon career in the early 1970’s, when there were barely a dozen ultras in the country (and not a single 100 mile trail race). At 6’2″ and 175 pounds, his physique was uncommon among the sport’s elite. He ran mostly 50 mile races because that was the longest distance he could find. In 1974 he finished second to Max White in the AAU National 50 Mile Championship. The JFK 50-miler, the oldest ultra in the country, just celebrated its 50th running in 2012. Barner ran the mixed trail/road course when it was only 10 years old and only one man had ever broken 7 hours on it. Barner won it in 6:29 (he would later run 6:23 there). In a span of eight years he broke 6 hours for 50 miles nineteen times, and ran between 6:00 and 6:15 another 12 times. In two of the few 100-mile races known to have been held in the U.S. prior to 1980 (both in New York City), Barner ran 13:41 (#3 on the U.S. all-time list at the time) and 13:57.

By the mid-70’s the 100km distance had emerged as the universal global benchmark event. The first certified 100km event in the U.S. was held at Lake Waramaug, CT in 1974. Park Barner won it (beating none other than Ted Corbitt) in 7:37:42, and that time became recognized internationally as the “American Record” for the distance. Over the course of the next 3 years Barner kept possession of that record, lowering it in three times until it came to rest at 7:11:44.

In October 1978, at Glassboro, NJ he entered one of the first 24-hour races held in the U.S. He ran steadily throughout to win with a total of 152 miles, 1599 yards. It was an astounding, world-class performance, over 18 miles further than what was generally regarded as the “American Record,” Ted Corbitt’s 6-year old mark of 134 miles, 782 yards. Eight months later he entered an invitational 24-Hour Race in Huntington Beach, CA. He improved by almost 10 miles, covering 162 miles, 537 yards and besting Englishman Ron Bentley’s World Record by almost a mile. His metronomic, even pacing was unprecedented for this distance range. No one in history had ever run for 24 hours the way he did it. His 50-mile splits were 7:14, 7:15, and 7:21. It took 12 years for an American (Rae Clark, last years’ Hall of Fame inductee) to run farther in 24 hours, and still today, 33 years later, Barner’s distance has been bettered only by 4 Americans.

Park Barner continued to run ultras through the mid-1980’s, then abruptly retired from the sport at the age of 40. In extending his racing range in his final racing years, his highlights included winning the Weston 6-Day race twice, with a best of 445 miles in 1982, and then three months later winning a 500 mile race across the state of Michigan (including a mandatory 8-hour curfew each night) in 6 days, 6 hours.

But it wasn’t just his record-breaking performances that made Barner a “living legend.” He had a unique depth of constitutional strength and resiliency. The stories of his “outside the box” exploits are nearly as impressive as those of his greatest races, and have contributed to his almost mythical status in the history of the sport. He was tolerant of all ranges of weather, but thrived in extreme cold. He commuted to and from his job by running along the Susquehanna River, never wearing more than a t-shirt and shorts, even in single-digit temperatures. His final American 100km record was run on a windy, bitterly cold day, with snow blowing sideways across the course and the temperature plummeting through the day. As the race progressed, most of his competitors added extra layers of clothing with each passing lap of the 10km course. But Barner did the opposite. He started with a jacket, hat, and gloves, but by the end of the race he was wearing nothing but racing shorts and a mesh singlet. To prepare for one of his 24-hour races, he did a training run from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh (203 miles), stopping only briefly in a diner for a piece of pie. In amongst his frequent ultra races he ran a marathon personal best of 2:37, then followed it the next day with a 2:39. His landmark 152+ mile 24-hour run in 1978 in New Jersey was a Friday-Saturday event. From there he took a bus to Baltimore and ran 8:16 to take 6th place (out of 13) in a 50-mile race on Sunday of the same weekend. In 1974 there was a 3-day, 300km stage race (100km each day) along the C&O Canal gravel/dirt towpath from Washington, DC to Cumberland, MD. Barner was the only finisher, with daily splits of 7:52, 8:12, and 7:48. Two years later, seeking a greater challenge, he asked the race director to include a straight-thru, continuously timed division. He ran the 300km nonstop (with nighttime temperatures below freezing) in 36:48. For the size of his physical frame, he was remarkably light on his feet, with impeccable form and an enviably graceful, loping stride. He was frequently referred to by his competitors as a “human metronome.”