Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:20 — 34.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

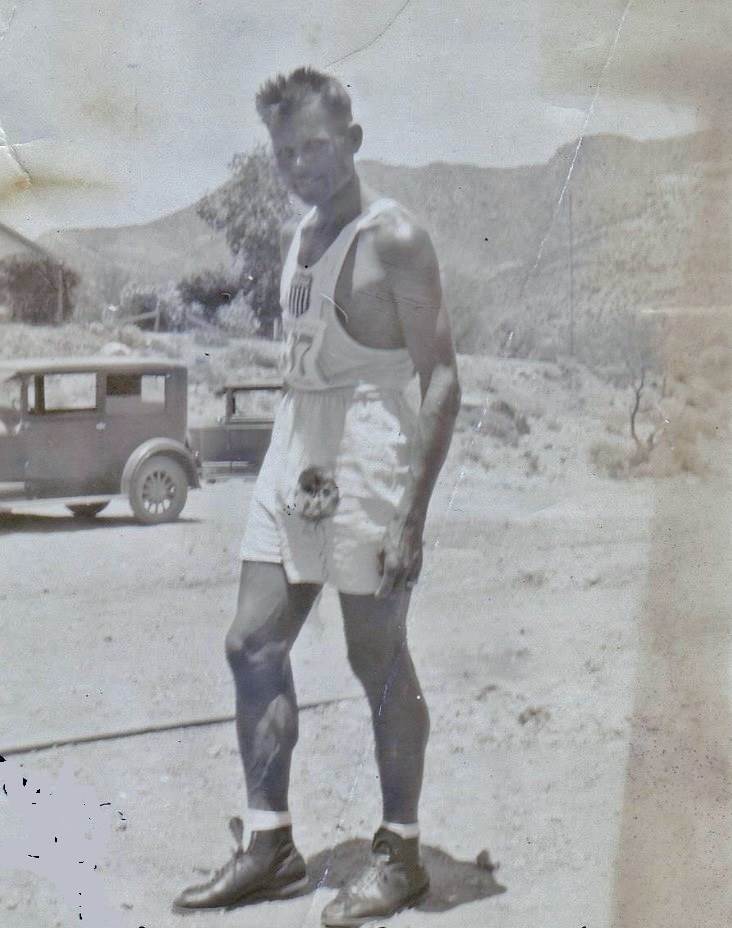

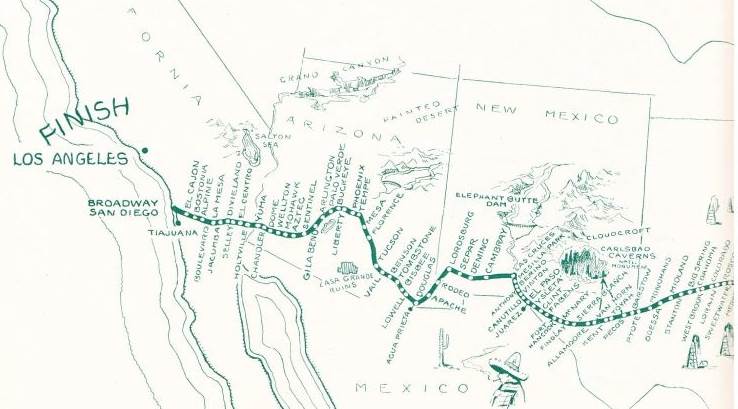

Johnny Salo, of Passaic, New Jersey, was the greatest American ultrarunner of the first half of the 1900s. This is part two of the story of his amazing life and the story of the 1929 “Bunion Derby.” If you haven’t already, go read Part One, Johnny Salo – 1928 Bunion Derby which highlights Salo’s rise to running fame when he placed second in the 1928 race across America in the “Bunion Derby.” In this concluding article, Salo’s fame grows even more when he ran in the 1929 Bunion Derby with perhaps one of the most exciting finishes in ultrarunning history.

Johnny Salo, of Passaic, New Jersey, was the greatest American ultrarunner of the first half of the 1900s. This is part two of the story of his amazing life and the story of the 1929 “Bunion Derby.” If you haven’t already, go read Part One, Johnny Salo – 1928 Bunion Derby which highlights Salo’s rise to running fame when he placed second in the 1928 race across America in the “Bunion Derby.” In this concluding article, Salo’s fame grows even more when he ran in the 1929 Bunion Derby with perhaps one of the most exciting finishes in ultrarunning history.

But sadly, his amazing running career soon was cut short by tragedy. You may want to find a tissue for the end of this story. This article attempts to celebrate the amazing accomplishments and impactful life of Johnny Salo. Once a huge hero, he has now been forgotten, even by his hometown of Passaic, New Jersey, and needs to be remembered again.

Plans for 1929 Bunion Derby

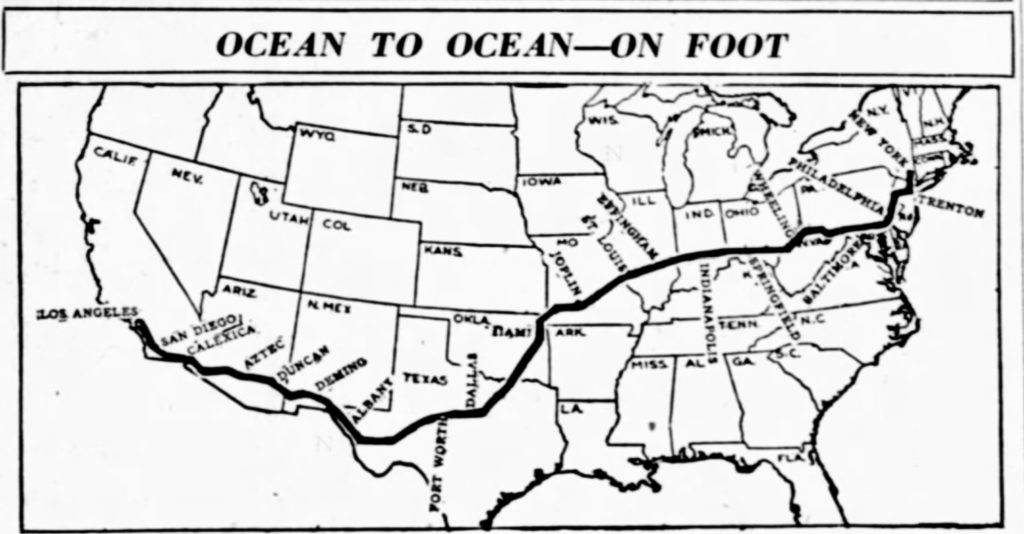

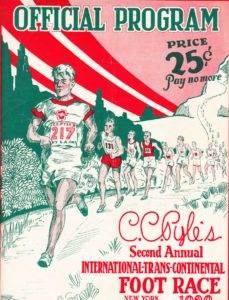

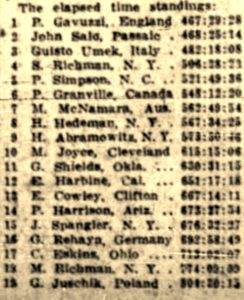

By Feb 1929, Charles C. Pyle (1882 – 1939), known as “Cash and Carry Pyle” was at it again, promoting an upcoming 1929 “International Continental footrace” (Bunion Derby) that this time would go from New York to Los Angeles with a more southern route. He traveled in his huge bus around to cities to get contract agreements signed for stopping points.

By Feb 1929, Charles C. Pyle (1882 – 1939), known as “Cash and Carry Pyle” was at it again, promoting an upcoming 1929 “International Continental footrace” (Bunion Derby) that this time would go from New York to Los Angeles with a more southern route. He traveled in his huge bus around to cities to get contract agreements signed for stopping points.

In March, Salo announced locally his intention to get unpaid leave from the Passaic, New Jersey police force to run in the 1929 Bunion Derby. An editorial in his hometown newspaper thought the idea was terrible. “For a long time after his return he was not altogether a well man Salo shouldn’t think of going into another such nerve-wrecking, body-breaking test of endurance. For his own sake and his family’s, he should be dissuaded from making this next race. His sturdy physique, weakened by the last effort could be shattered in the next.”

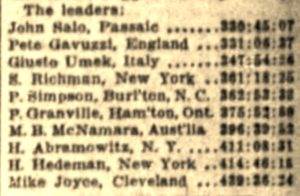

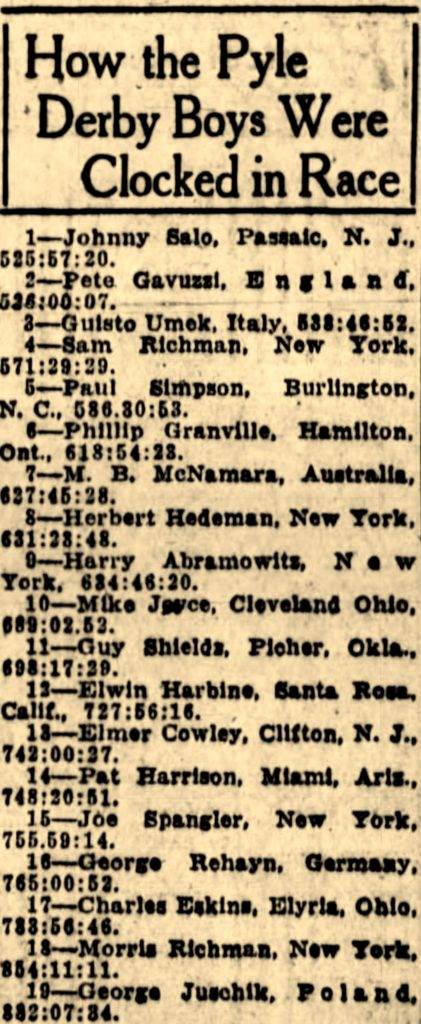

By late March, 81 runners from 14 countries had gathered at Pyle’s training camp on Long Island preparing for race day. They all sought to win the $25,000 first place prize or at least finish in the top fifteen to get a piece of the total $60,000 pot. About 30 of the 1928 Bunion Derby runners returned to run again.

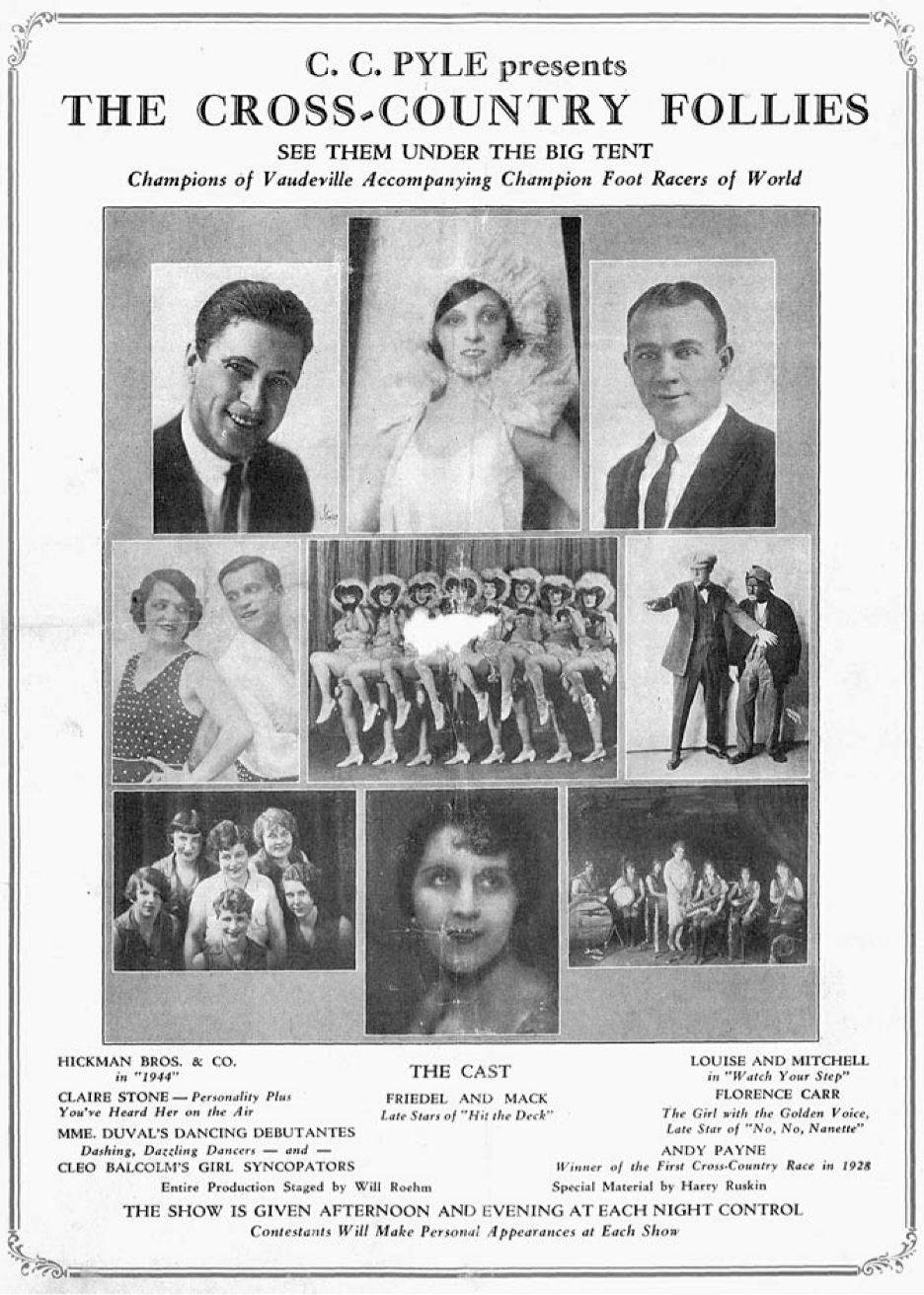

The 1928 winner, Andy Payne wouldn’t try to defend his title. “The Oklahoma farm boy, now quite wealthy through the purchase of coal and oil land, will go along as a helper.” He would be Pyle’s, public figure head, be a featured attraction at Pyle’s nightly side-show, and would also act as the “chief patrolman” during the daily runs, aiding runners and crews.

The Start

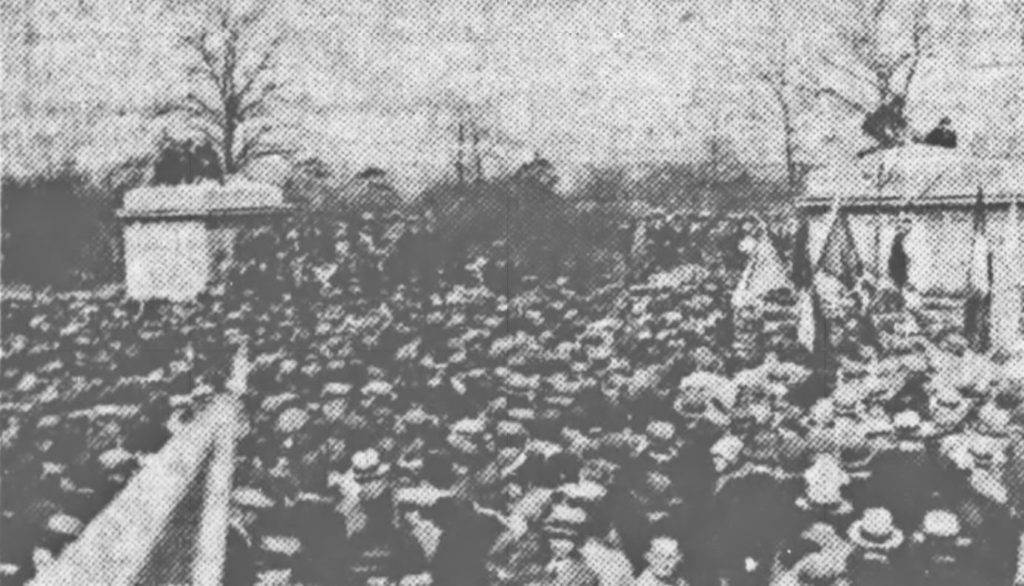

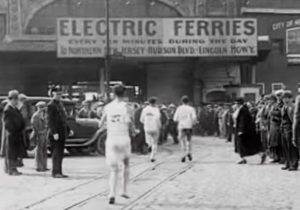

The 1929 Bunion Derby began on March 31, 1929. An estimated 50,000 people jammed Columbus Circle in New York City for the send-off. Steve O’Neill, football star of the New York Giants pulled the trigger of the starting gun. The runners first ran 2.5 miles to board an electric ferry on 23rd street (Pier 63) to cross the Hudson River.

About 500,000 people lined the route to Elizabeth, New Jersey, the first stopping point. Police in Elizabeth enforced its Sunday “blue laws” and refused to let Pyle put up his evening side show.

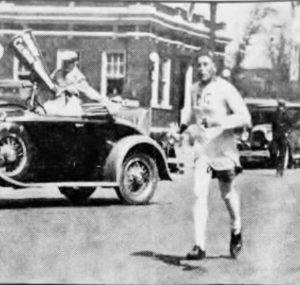

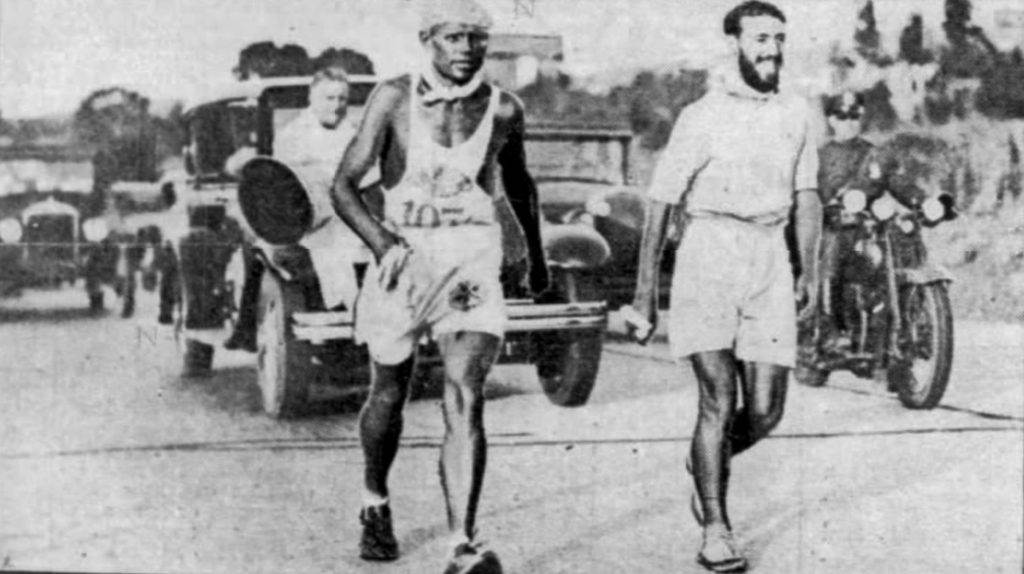

Salo unfortunately became ill early because of the heat, so he took it easy on that first day. But all along the way, he was the center of attention among the fans. Many would ask, “where is Salo?” He ran along in his same usual stride. A Passaic motorcycle cop, Michael Palko (1897-1975), opened up a running lane ahead as they entered Elizabeth, New Jersey where Salo finished in 10th place for the first day.

William “Bill” Wiklund (1907-1980), his trainer, and Salo’s wife Amelia, who was also part of his crew driving along, helped him the best they could to overcome his stomach trouble. Wiklund, also Finnish-American, had been the captain of the champion Passaic High cross country track team in 1924, so had some good running experience to apply to his trainer role.

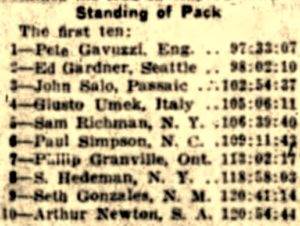

On the second day, Hardrock Simpson (1904-1978) led the runners as they ran toward Trenton, New Jersey, and Salo was in third. A cold rain fell on them as they passed Princeton. “Salo refused to chase the leaders. He declared that real competition would not develop for two weeks and in the meantime, he would be content to remain close to the leaders.”

The city of Trenton wouldn’t let Pyle put up his sideshow, so the runners continued across the Delaware River to stop at Morrisville, Pennsylvania. “A few of the runners already have felt the effects of the pavement pounding and the trainers were busy soothing aching dogs and administering to incipient blisters.” Two runners were already out. One tripped and fell as he finished the first stage and another had been struck by an automobile.

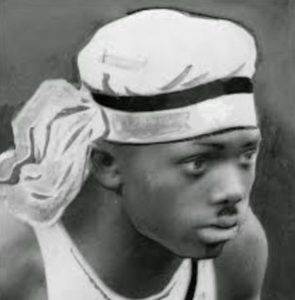

Running out of Trenton, New Jersey on day three, Salo narrowly escaped meeting disaster when an automobile brushed him. “Johnny leaped to the sidewalk but could not hold his footing and went sprawling except for a few scratches, however he was uninjured.” He ran a couple days with the very talented African American runner, Ed Gardner (1898-1966) from Seattle, Washington. They had become friends the previous year.

Delaware

Salo won his first stage on day four, tied with Peter Gavuzzi (1905-1981) of England. Gavuzzi was a world class ultrarunner who was leading the 1928 Bunion Derby late but had to pull out due to badly infected teeth. On this day, Salo had been leading, but when he stopped for a drink, Gavuzzi sped past him. Salo was determined to catch him. After fifteen miles he caught up and they went into the control point at Wilmington, Delaware together.

Maryland

Many of the runners were shivering in a drizzle as they lined up for the roll call and start of the day’s 40-mile run to Baltimore, Maryland. Some were covered in raincoats. Salo tied for second that day. It was said that the early betting among the “bunioneers” was favoring Salo to finish first or second. Only a few Baltimore citizens came out to watch the runners.

The weather made things tough on the crews too. “The army of trainers and attendants who accompany the runners in trucks, apparently decided that the grounds were too muddy for tenting. With few exceptions, quarters were found in hotels.”

For Pyle’s nightly sideshow, he decided that the tent was just too big. It took too long to raise every night with many men. He sent it back and, in the meantime, performed in theaters until a smaller tent arrived.

For Pyle’s nightly sideshow, he decided that the tent was just too big. It took too long to raise every night with many men. He sent it back and, in the meantime, performed in theaters until a smaller tent arrived.

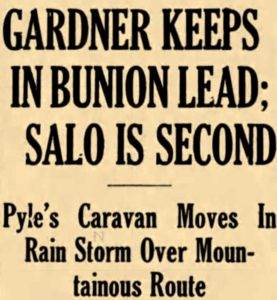

Salo took the overall lead at Fredrick, Maryland. The following day, Salo and Gardner (in overall second) dueled for 36 miles in scorching sun. “Gardner hopped into the lead at the start and was ahead a mile and a half before Salo started to chase him.” He caught him after two hours and they ran neck and neck. Salo pushed into the lead, but after drinking some milk, his stomach rebelled, allowing Gardner to take the day’s 52-mile victory. Four runners dropped out on that tough day.

Salo lost his overall lead as they hit the hills in the Cumberland Mountains. Fearing shin splints, he walked up most of the hills. He said he wasn’t worried about losing the lead. “There will be plenty of opportunities in this race. It is too early to think about getting a lead and holding it.”

Pennsylvania

The runners faced one of the toughest stages of the entire race when they had to run 63 miles up and over the Allegheny Mountain range to Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Salo did not eat any breakfast and in the morning suffered from stomach issues. A heavy downpour of rain slowed everyone down but was a welcome relief from the torrid heat of the past few days.

The runners faced one of the toughest stages of the entire race when they had to run 63 miles up and over the Allegheny Mountain range to Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Salo did not eat any breakfast and in the morning suffered from stomach issues. A heavy downpour of rain slowed everyone down but was a welcome relief from the torrid heat of the past few days.

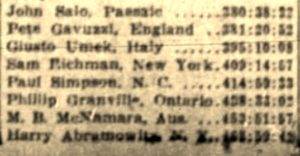

By the end of the stage, Salo was trailing the overall leader Gardner, by an hour and a half. The next day, still with stomach problems. “he was forced to stop a dozen or more times in the 33 miles and could not hold down any food. It is believed that water he drank in Cumberland, Maryland combined with the sudden change in weather, was responsible for his condition.” Only 34 of the 81 starters remained in the race.

West Virginia

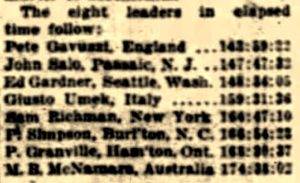

After wallowing through the mud for nearly eleven hours without anything to eat, Salo finished fifth on the 12th day at Wheeling, West Virginia. Overall, after 500 miles, he was overtaken by Gavuzzi and had slipped into third place. For a time, they had to truly run on trails. “Because of the poor condition of roads taken, consisting of little more than cow paths, it was impossible for the trainers to follow them in automobiles, hence Bill Wiklund, Salo’s trainer, could not give him food or water during the run. Salo was also forced to run in a heavy downpour of rain without adequate protection.”

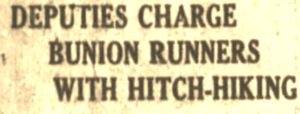

Sheriff deputies in West Virginia reported that on the leg from Wheeling, West Virginia, that there were many runners who disappeared from the course during the 50-mile leg and received rides from motorists. “The deputies also said rebellion had split the ranks of the runners with hose actually running aligned against those hitch-hiking.”

Sheriff deputies in West Virginia reported that on the leg from Wheeling, West Virginia, that there were many runners who disappeared from the course during the 50-mile leg and received rides from motorists. “The deputies also said rebellion had split the ranks of the runners with hose actually running aligned against those hitch-hiking.”

Ohio

Stunning reports reached Passaic that Salo had broken his leg in Ohio. It was a cruel hoax. Salo finally recovered from his stomach trouble after entering Ohio. He picked up his speed and finished second on two consecutive stages to Zanesville and Columbus.”

Ohio was rough. “Unpleasant weather and poor receptions for the patient plodders at most of the stops spread a feeling of depression over the bunioneers. Pavement pounders shivered in unseasonable cold as they shuffled into Springfield.”

At Springfield, Ohio, Solo’s discouraging illness returned. He still didn’t panic and finished in sixth in cold weather and rain. One runner quit because he “didn’t feel like running anymore.”

Indiana

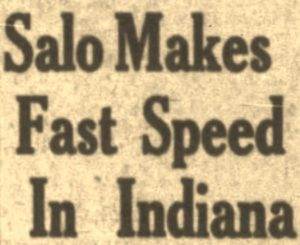

Salo returned to his old form as he won the 17th stage into Richmond, Indiana, covering 63 miles in an impressive 8:47:10 despite a stiff headwind along the bleak, unpopulated, lonely road. Crowds lined the streets of Richmond as he finished his impressive run that day. It was commented, “If anyone has any doubts about that feat being one of the greatest accomplishments of the 1929 athletic season in any branch of sports, let him come out here and tell it to the residents of this Hoosier state community.”

Salo returned to his old form as he won the 17th stage into Richmond, Indiana, covering 63 miles in an impressive 8:47:10 despite a stiff headwind along the bleak, unpopulated, lonely road. Crowds lined the streets of Richmond as he finished his impressive run that day. It was commented, “If anyone has any doubts about that feat being one of the greatest accomplishments of the 1929 athletic season in any branch of sports, let him come out here and tell it to the residents of this Hoosier state community.”

The following day Salo again lead the runners, completing 34.7 miles in 4:25:45, cutting nearly a full hour off of the lead. He said, “I feel like running so why hang back.”

Salo made it a three-peat win into Indianapolis, covering 35.3 miles in 4:27:15. “Salo tore along the road as if he were trying to reach Los Angeles before the sun dipped in the West. He was going so fast that he sped past the timer’s table at the finish.”

Arthur Newton, running in 9th place was struck by an automobile and suffered and dislocated shoulder. He would continue traveling with the race assisting Gavuzzi.

Illinois

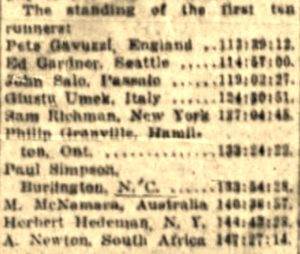

Salo took over second place overall, running into Effingham, Illinois, winning a 52.4-mile stage in 7:11:45. “Salo had a lonely time in the run. Most of the day a cold rain fell as lightning cracked and thunder growled. He was far ahead until five miles from the finish when Giuato Umek caught him and tried to pass him. Johnny advanced his spark and tore down the main street four minutes ahead of the Italian runner.”

Salo took over second place overall, running into Effingham, Illinois, winning a 52.4-mile stage in 7:11:45. “Salo had a lonely time in the run. Most of the day a cold rain fell as lightning cracked and thunder growled. He was far ahead until five miles from the finish when Giuato Umek caught him and tried to pass him. Johnny advanced his spark and tore down the main street four minutes ahead of the Italian runner.”

The American Legion from Passaic wrote letters to many of the Legion posts in cities along Salo’s route asking them to give aid to him. Many responded. A person from a post in Vandalia, Illinois wrote back to the Passaic post, “We were delighted to entertain Comrade John Salo last night and I assure you everything was done to make him and his wife comfortable while in our city. I assure you we were only too glad to do this. He told me this morning he was feeling fine and went away from here leading the bunch.”

The American Legion from Passaic wrote letters to many of the Legion posts in cities along Salo’s route asking them to give aid to him. Many responded. A person from a post in Vandalia, Illinois wrote back to the Passaic post, “We were delighted to entertain Comrade John Salo last night and I assure you everything was done to make him and his wife comfortable while in our city. I assure you we were only too glad to do this. He told me this morning he was feeling fine and went away from here leading the bunch.”

Salo chalked up another stage win running 59.8 miles in 8:12:50 into Collinsville, Illinois. He said, “A dog ran after me near a farm. I had to run!” There were only 28 runners left in the race and so far, they had covered 1,036 miles.

Missouri

Ed Fetting, a former professional basketball player who wrote for a St. Louis Newspaper, composed a column about Salo. “The other morning as I stood at the foot for Free Bridge that crosses the Mississippi River in Missouri, I saw a little sun-baked figure trotting along the highway. No one to the right of him, no one to the left of him. He seemed as a phantom runner coming out of some unknown world. Pressing on, he passed the throngs with eyes glued to the trail before him. Not a glance toward the curious, not one smile for the cheering. Into free air again, where he and his thoughts could go steadily on, on, and on. It was Johnny Salo, the Finn from Passaic.”

At Maplewood, a suburb of St. Louis, the fire station there opened up their facilities for Salo to stay in. Checking his weight there, he was 145 pounds, having lost 11 pounds since the race started. His left hip and leg muscles had been giving him quite a bit of pain for the past three days. To the firemen, he pointed to his bandage toes and said, “I lost two nails yesterday and I guess I’ll lose another one tomorrow.”

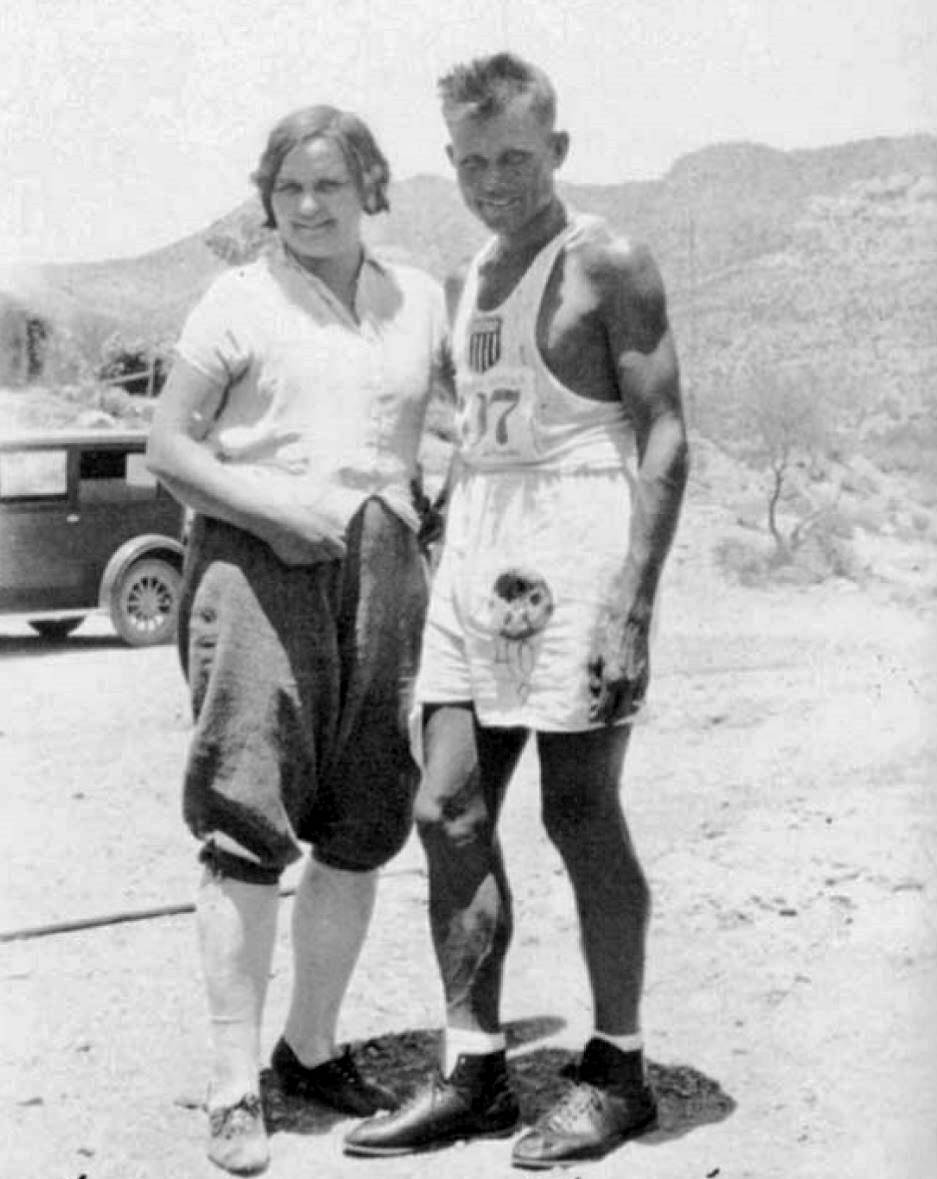

Salo praised one of his trainers, his wife, Amelia, who had joined his crew at Columbus, Ohio. “She’s the only woman trainer in the race. And man, she’s a good one. The best I ever saw, and just learnin’ too.” Amelia, also an athlete when she was younger, was credited for bringing Salo out of his stomach illness when it seemed certain he would have to quit.

Salo gained nearly a full hour on Gavuzzi by winning a 61-mile stage in 8:42:10 to Sullivan, Missouri. That stage had been the toughest of the first 26 stages. “Strong headwinds made it impossible to maintain a stead gait, the gale at times checking the runners completely. A cold penetrating rain fell all day to add to the discomfort.”

On the following day, the three leaders ran together. “Salo, Gardner, and Gavuzzi narrowly escaped injury on the road when a motorcycle swerved into them. Gavuzzi wrenched his back getting out of the way, and Salo made a grab for the driver and, failing to catch him, tossed a stone at him. It was low and on the outside, and the wild driver took the base.”

On the following day, the three leaders ran together. “Salo, Gardner, and Gavuzzi narrowly escaped injury on the road when a motorcycle swerved into them. Gavuzzi wrenched his back getting out of the way, and Salo made a grab for the driver and, failing to catch him, tossed a stone at him. It was low and on the outside, and the wild driver took the base.”

Gavuzzi, knowing that his lead was decreasing went on a “heart-breaking” pace the next day to gain 20 minutes by running 41 miles in 4:41:10 to Springfield, Missouri which was thought to be an unofficial world best for that distance.

After the next day, Salo was nearly four hours behind first place Gavuzzi overall. Salo said he had eaten too much the night before and had no pep in the morning. He also mentioned that he had seen a snake wiggle across the road in front of him and was so frightened he couldn’t breath easy for ten minutes. “I’m scared of snakes and I’m going to buy a gun and ammunition.”

The next day a terrible wind and hail kept the snakes away and Salo won the stage to Joplin, Missouri, because it was said Gavuzzi’s long beard caught the wind and held him back.

Oklahoma

Salo cut 20 minutes off the lead running the 32nd stage into Miami, Oklahoma, running 36.7 miles on bumpy clay roads in 4:36:50 with Sam Richman. He was nearly nine hours ahead of Gardner in third place. Sadly, Gardner gave up the race the next day due to shin splints.

“Salo narrowly escaped serious injury along the rough roads. A Texas car, made him jump to the center of the road as it sped past him. Another car going in the opposite direction passed at the same time and almost struck him.”

“Salo narrowly escaped serious injury along the rough roads. A Texas car, made him jump to the center of the road as it sped past him. Another car going in the opposite direction passed at the same time and almost struck him.”

Only 24 runners were still in the race as they ran a 60-mile stage to Holdenville, Oklahoma. It was truly Salo’s day as he finished first in 8:06:40 and trimmed Gavuzzi’s lead to less than two hours. “The American Legion took Salo in hand and gave him food and lodging for the night. He was given a tremendous ovation as he checked in by the thousands that lined the streets.” The next day, Gavuzzi reclaimed the minutes that Salo had gained.

A reporter from Salo’s hometown newspaper, Arthur G. McMahon rode along covering the race. He recalled, “Many a hot night I hitch-hiked sixty miles to the nearest telegram station to file my story after the runners had been safely tucked in bed. Sometimes I had to wake up sleepy telegraphers on a railroad line. Other times I had to pound on doors of dingy telegraph offices to awaken someone to take my messages.”

Texas

Salo lost 29 minutes on a long 74-mile stage going into Texas. His wife, Amelia said, “Johnny Salo eats too much. He eats all day and all night. How can he run?” He argued back, “Well, I am hungry and I’m going to eat. Sometimes at midnight I get hungry and have to get out of bed and eat.”

![]() On the 41st day, Salo ran 80 miles to Dallas in 11:22:15 “and jumped up the steps of the famous Oak Cliff High School at the finish line with a smile on his bronzed face. He was anxious to talk after his lonely sojourn on the red clay roads. ‘I ran a mile out of my way, but that’s all right. Sure it was a pretty tough grind, but here I am.’” He sliced 52 minutes from Gavuzzi’s lead.

On the 41st day, Salo ran 80 miles to Dallas in 11:22:15 “and jumped up the steps of the famous Oak Cliff High School at the finish line with a smile on his bronzed face. He was anxious to talk after his lonely sojourn on the red clay roads. ‘I ran a mile out of my way, but that’s all right. Sure it was a pretty tough grind, but here I am.’” He sliced 52 minutes from Gavuzzi’s lead.

The press recalled what a stir was caused two years earlier when the Tarahumara ran 89 miles to Austin in 14:46. At that time, they had been branded “superhuman.” “More than one columnist commented on the fact that the youth of American couldn’t hold a candle to the Tarahumara in the matter of endurance. And yet today, John Salo, rambled 80 long miles in 11:22.” And he did it after running an ultradistance run for 40 straight days It indeed was a far more impressive performance.

For the next four days it was said that Salo “loafed along the way,” doing much walking, content to finish near Gavuzzi. “The cop and the Italian joked along the highway, making no effort to win the lap.”

For the next four days it was said that Salo “loafed along the way,” doing much walking, content to finish near Gavuzzi. “The cop and the Italian joked along the highway, making no effort to win the lap.”

The true race resumed on a 39.4-mile stage to Anson, Texas. “Salo sped over the rough Texas roads beneath a broiling sun at high speed, although the sun slowed all the boys down.” Salo won the stage in 5:08:05, trimming nineteen minutes off the lead. The runner’s camp was swept by a heavy sandstorm soon after the last man checked in. The next day Salo climbed within less than an hour of the lead to Sweetwater, Texas. “He was in good shape when he checked in and trotted around the hall after the time clocked him.”

Wiklund, Salo’s trainer later said, “People don’t realize the tremendous stamina a runner must possess to finish a race like the Bunion Derby. In Texas, the rain was like ice water and the hail came down so hard the runners were busied. When it wasn’t raining the sun was beating down on the athletes. Sometimes they were so badly sunburned they couldn’t lie down in comfort at night. They had to get up and run the next day, just the same.”

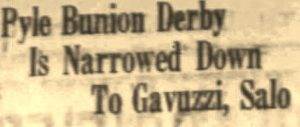

Salo vs. Gavuzzi

With still about 1,400 miles to go, race predictors felt the winner would be either Gavuzzi or Salo. “Gavuzzi runs easier than Salo. He is a small man, no more than five feet, four inches and weighs about 126 pounds. He has an easy stride and is unbeatable over forty-five miles. He has a cheerful word when he checks in and immediately grabs his pipe for an evening’s smoke.”

“Salo, on the other hand, looks strained when he pounds the highway. He looks neither to the right or left, and a wave of the hand is ignored by him. When he stops to eat or drink or change shoes, he has little to say. When checking in, however, he generally has a wide smile and stops to talk for a few minutes.”

“It is hard to make a selection between Gavuzzi and Salo. If the outcome depended upon the last two or three days, Gavuzzi would win. He is fast as groomed lightning and can set a terrific speed for long distances over two or three days. Should the last two weeks decide the winner, however, the wise money would ride on Salo. His strength, stamina, and ability to cover grueling grinds at a fast pace constantly, would win for him.”

“It is hard to make a selection between Gavuzzi and Salo. If the outcome depended upon the last two or three days, Gavuzzi would win. He is fast as groomed lightning and can set a terrific speed for long distances over two or three days. Should the last two weeks decide the winner, however, the wise money would ride on Salo. His strength, stamina, and ability to cover grueling grinds at a fast pace constantly, would win for him.”

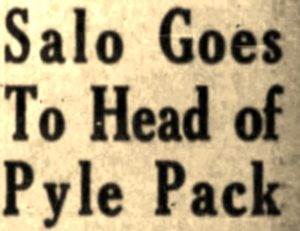

West Texas

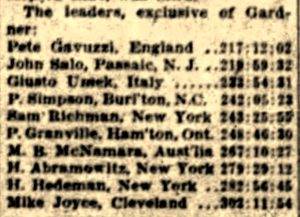

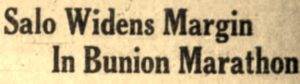

After trailing Gavuzzi overall for 1,200 miles, Salo finally took the lead by four minutes after 40-mile stage to Midland Texas. For the next few days they kept each other in sight. “These boys are going to have a great battle for the remainder of the trip. Every day thousands struggle for a view of them along the roads. A cold cutting rain that made the lonely Texas roads appear even more desolate fell on the patient plodders.”

After trailing Gavuzzi overall for 1,200 miles, Salo finally took the lead by four minutes after 40-mile stage to Midland Texas. For the next few days they kept each other in sight. “These boys are going to have a great battle for the remainder of the trip. Every day thousands struggle for a view of them along the roads. A cold cutting rain that made the lonely Texas roads appear even more desolate fell on the patient plodders.”

The two leaders continued to run together through west Texas. “They are a great pair, these leaders. Good friends despite the rivalry between them. A heavy rain fell on them, lightning flashed and thunder rolled, but both laughed and joked as they jogged along. Running through the heat of the Texas oil fields, the runners saw trees for the first time in almost two weeks. Otherwise it was the same wide open spaces with wide-eyed cattle watching the procession in bewilderment.”

Getting closer to the Mexican border, “Salo, attired in a Mexican hat, did a war dance every 700 yards or so. When he came to a brook, he suggested going for a swim. The idea was voted down, however, by the other runners.”

Passaic New Jersey’s newspaper finally admitted its editorial was wrong a couple months earlier that was opposed to Salo’s decision to run the race again. “We thought it would be too much for him but we were wrong and so we are glad to admit the fact. May he show his heels to the rest of them all the way to the Coast! So here’s to Johnny Salo. May he come through first.”

On the 57th day, Salo again seriously raced during a very hot 59.4-mile stage to Fabens, Texas near the Rio Grande. “Umek and Salo battled hard for the lead for twenty miles, averaging nine and a half miles an hour in their anxiety to finish first. A blazing sun beat down on them unmercifully, making it necessary for them to take refreshments every half mile. Thirty-five miles out, with the hills of Mexico in sight and the Rio Grande flowing along the road, they jogged together over the border highway.” Umek’s car broke down, so Salo’s crew cared for Umek. They tied for the stage win.

Mexico

![]() The race crossed over into Mexico because El Paso’s chamber of commerce wouldn’t agree to a Pyle contract to let the race stop in their city. “The boys checked in at the foot of the International Bridge leading into Juarez, Mexico, and those who were eligible, including Salo, went across the Rio Grande into foreign territory.”

The race crossed over into Mexico because El Paso’s chamber of commerce wouldn’t agree to a Pyle contract to let the race stop in their city. “The boys checked in at the foot of the International Bridge leading into Juarez, Mexico, and those who were eligible, including Salo, went across the Rio Grande into foreign territory.”

New Mexico

The next day they ran into New Mexico, reaching Las Cruces. Salo held a 40-minute lead. “With less than three weeks of the race remaining, things are bound to pop soon. It is going to be a battle to the death, and the winner right now is a toss-up.”

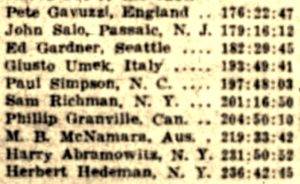

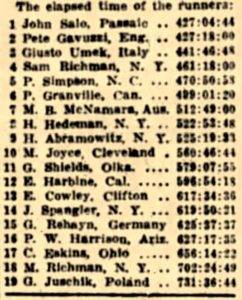

![]() The race did start heating up again the next day when Gavuzzi excelled in a true desert 63-mile stage to Deming New Mexico, covering it in 8:14:30, taking back Salo’s ten-day lead and pushing it to 21 minutes. The hot desert was tough and only seven runners finished in under 12 hours. There were only 19 runners left in the race. Compare that to the 55 who finished in 1928.

The race did start heating up again the next day when Gavuzzi excelled in a true desert 63-mile stage to Deming New Mexico, covering it in 8:14:30, taking back Salo’s ten-day lead and pushing it to 21 minutes. The hot desert was tough and only seven runners finished in under 12 hours. There were only 19 runners left in the race. Compare that to the 55 who finished in 1928.

Arizona

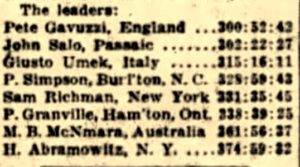

Running into Arizona, “Gavuzzi never let Salo get out of his sight and when Salo spurted, Gavuzzi paced him, always a foot or two behind. They finished hand in hand in third place.” After covering 2,883 miles, they were on a pace 70 hours faster than the race in 1928.

Salo took the overall lead back at Safford, Arizona. “Salo is in perfect shape, looking better than in weeks, and in excellent spirits. He will be hard to push aside. His ability is strengthened by confidence.”

But the lead was short-lived and ping-ponged back to Gavuzzi at Miami, Arizona, claiming a 16-minute lead with only 13 days remaining. The next day, the ball was back on Salo’s side of the table as he took a 13 minute lead after a short 21-mile stage to Superior, Arizona that Salo sprinted in 2:38 over grueling hills and sharp grades.

But the lead was short-lived and ping-ponged back to Gavuzzi at Miami, Arizona, claiming a 16-minute lead with only 13 days remaining. The next day, the ball was back on Salo’s side of the table as he took a 13 minute lead after a short 21-mile stage to Superior, Arizona that Salo sprinted in 2:38 over grueling hills and sharp grades.

All were curious who would come out on top during a 51-mile grind to Mesa, Arizona. “Salo was in great condition today and his running over the arid wastelands was a treat to behold. He declared at the finish that he never felt better during the race and expressed regret that the lap wasn’t longer.” He finished the 51 miles in a blazing 6:34:55.

Salo’s lead grew to more than an hour. He stretched it even further on the next 54.2-mile stage to Buckeye, Arizona, future home of the Across the Years race. Gavuzzi commented afterward, “He is either not human or superhuman. He is so far ahead I can’t see him.” By mistake, Salo took a wrong turn in Phoenix cutting off a half mile, costing him a eight minute penalty.

Salo’s lead grew to more than an hour. He stretched it even further on the next 54.2-mile stage to Buckeye, Arizona, future home of the Across the Years race. Gavuzzi commented afterward, “He is either not human or superhuman. He is so far ahead I can’t see him.” By mistake, Salo took a wrong turn in Phoenix cutting off a half mile, costing him a eight minute penalty.

On a 44.4 mile stage from Gila Bend to Aztec, Arizona Gavuzzi ran desperately to overcome Salo’s lead, running a heart-breaking pace for 30 miles leaving Salo far behind. Gavuzzi gained 17 minutes back, still 69 minute behind, but proclaimed that he would regain the lead within two days.

Gavuzzi backed up his bravado the next day by gaining another 30 minutes as Salo was bothered by the heat. “Only a blazing sun that beat down on the desolate desert roads prevented Gavuzzi from assuming the lead. Both Gavuzzi and Salo are dog tired.”

Mexico again

As Gavuzzi predicted, he took the lead the next day on a 44-mile stage to Algodones, Mexico, across the border from Yuma, Arizona. Salo lost an hour and a half in time to him, giving Gavuzzi a lead of nearly an hour. “Handicapped by stomach trouble, aggravated by natural exhaustion from his hard running, Salo turned in one of his poorest runs of the derby. He gamely plugged on despite his trouble.” With only six days left, it didn’t look good for Salo. He seemed to be heading for another second place finish.

As Gavuzzi predicted, he took the lead the next day on a 44-mile stage to Algodones, Mexico, across the border from Yuma, Arizona. Salo lost an hour and a half in time to him, giving Gavuzzi a lead of nearly an hour. “Handicapped by stomach trouble, aggravated by natural exhaustion from his hard running, Salo turned in one of his poorest runs of the derby. He gamely plugged on despite his trouble.” With only six days left, it didn’t look good for Salo. He seemed to be heading for another second place finish.

California

On the next stage into California, Gavuzzi refused to let Salo get away from him and they “compromised on a tie as they ran together over desert roads beneath the blistering sun. The agreement clearly favored Gavuzzi as the finish was getting closer.

There was no agreement on the next day, a 58-mile stage to Jacumba, California. “Salo won the most grueling grind of the race entirely uphill beneath the hottest sun of the year.” He covered the distance in 9:09:05 and cut 36 minutes off of Gavuzzi’s lead. “That Johnny meant business was easy to see at the start in the morning. He was quiet and reserved, his attitude generally when he intended to run hard. He took the long steep hills at a fast gait while Gavuzzi walked up most of the grades.”

There was no agreement on the next day, a 58-mile stage to Jacumba, California. “Salo won the most grueling grind of the race entirely uphill beneath the hottest sun of the year.” He covered the distance in 9:09:05 and cut 36 minutes off of Gavuzzi’s lead. “That Johnny meant business was easy to see at the start in the morning. He was quiet and reserved, his attitude generally when he intended to run hard. He took the long steep hills at a fast gait while Gavuzzi walked up most of the grades.”

One poor runner George Rehahn (1902-1978) had an unfortunate experience while crossing the Mohave Desert. “One day, as was his habit, he ran up to an automobile service station, picked up the sprinkling can which is used to fill radiators, and drank deeply therefrom. After quaffing several mouthfuls, he discovered it was kerosene. He was ill for a few days and finished out of the money.”

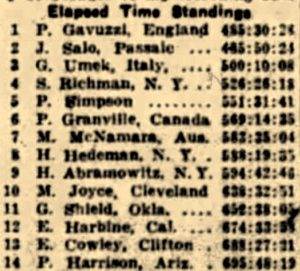

Salo and Gavuzzi tied in a 78.5-mile stage to San Diego. “Salo has two days to overcome the advantage and pile up a lead. It is highly improbable that if the winner is to be decided on the last lap he will beat Gavuzzi.

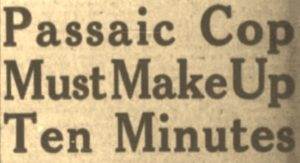

Things got really interesting, setting up a wild finish, as Salo pulled within ten minutes the next day to San Juan Capistrano, California. The stage was about 70 miles. “Both men fought savagely as they ran along the beautiful Pacific Coast Highway. Gavuzzi, his face lined from exhaustion, dragged his weary frame into the control point and witnessed the official timer reduce his margin. What a battle they put up after seventy-six days of running. Worn from the stiff grinds of the last two days, they walked much of the way, one refusing to let the other out of his reach. Then as darkness settled and the monotonous rumble of the ocean broke the silence, the flying cop braced himself and spurted. Gavuzzi wobbled slightly and gave chase but was not strong enough to withstand the assault. It was the most beautiful battle of the race.”

Things got really interesting, setting up a wild finish, as Salo pulled within ten minutes the next day to San Juan Capistrano, California. The stage was about 70 miles. “Both men fought savagely as they ran along the beautiful Pacific Coast Highway. Gavuzzi, his face lined from exhaustion, dragged his weary frame into the control point and witnessed the official timer reduce his margin. What a battle they put up after seventy-six days of running. Worn from the stiff grinds of the last two days, they walked much of the way, one refusing to let the other out of his reach. Then as darkness settled and the monotonous rumble of the ocean broke the silence, the flying cop braced himself and spurted. Gavuzzi wobbled slightly and gave chase but was not strong enough to withstand the assault. It was the most beautiful battle of the race.”

The Finish

June 16, 1929 was the last day of the race to Los Angeles. The race started at 7:40 p.m. at Huntington Park and went for a four-mile run to Wrigley Park, the home of a minor league baseball time, the Los Angeles Angels. There, they would run laps for 26 miles in front of a crowd to finish the race. Salo started at a terrific pace and had chopped four minutes off Gavuzzi’s lead by the time he reached Wrigley Field.

To finish things off, they needed to run 131 laps for 26.2 miles. “Salo’s running was beautiful to behold. He clicked off twelve miles an hour in spurts, his lips set in determination, his face drawn with weariness and pain, his powerful bronzed legs pounding, pounding, pounding, as he drew away.” He caught up to Gavuzzi’s overall lead by mile 12 and then went four minutes ahead by the half marathon mark. Salo tired and Gavuzzi put on a push, but only gained back a couple minutes.

“Gavuzzi sprinted occasionally but his morale was broken. He ran with his head down, eyes on the ground. His fingers clenched nervously as he fought valiantly to catch Salo. But it was the Flying Cop’s night and he gave Los Angeles sports fans the more marvelous exhibition of powerful running it has been their pleasure to behold.”

The winner

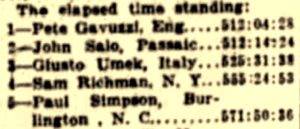

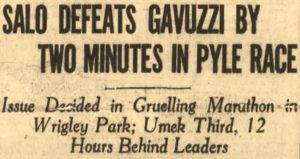

Salo was the winner of the final stage and was the winner overall by just two minutes, forty-seven seconds over Gavuzzi. His finish time was about 50 hours faster than Andy Payne ran the other direction in 1928.

Salo was the winner of the final stage and was the winner overall by just two minutes, forty-seven seconds over Gavuzzi. His finish time was about 50 hours faster than Andy Payne ran the other direction in 1928.

At the finish, Salo gave huge credit to his trainer Bill Wiklund and his wife Amelia who bathed his wounds during the 78 days. With arms around them, he was given a tremendous ovation from 10,000 people when the official results were announced. “A real champion, a real man. Passaic can claim him as its own pride.”

Back in Passaic, New Jersey, from 9 p.m. on, the telephone switchboard was swamped with calls all night until word was finally received when the race ended about 3 a.m. Eastern time. There were more than 3,500 calls more than normal. A crowd with as many as 500 people gathered in front of the newspaper building seeking news. The Police Commissioner, Benjamin F. Turner (1873-1950) was up all night until he received word from the Associated Press that Salo had won. He sent a telegraphy message to Salo that read, “Good boy, Johnny. Congratulations. I knew you would do it.”

Salo’s hometown reporter on scene said, “Salo ran a great race that last day. He was a ten to one shot to lose, but he showed the west coast fans that he is the world’s greatest runner and 10,000 cheered wildly, standing on their feet throughout the last ten miles of the grind. It was a great finish to a 3,600-mile race. Imagine less than three minutes decided the race.”

Wiklund, Salo’s trainer said, “What a heart that man has and what stamina. If we hadn’t had more than our share of bad breaks, the race would not have been as close. Once, when he hit the Rocky Mountains his stomach went back on him and he stopped six hours behind. No matter how sick he was the night before, he got up next morning feeling fit to run the race of his life.”

Gavuzzi’s heart-breaking loss

But the loss was heart-breaking to Gavuzzi. Many years later when both Pyle and Salo were dead, he would claim that the starter on the last day said they weren’t racing the first four miles to Wrigley Park, that they would start the marathon together at the park. Clearly other runners didn’t have that understanding. Gavuzzi said that he was held up by traffic and by a very long freight train on the way. But Salo and others went all out and Gavuzzi was only four minutes behind them when arriving at the park. The story doesn’t add up. He still had the overall lead on the track. Salo ran the final 26.2 marathon more than eight minutes faster that Gavuzzi.

Gavuzzi never issued a formal protest at the time. He claimed that Newton talked him out of it. Nothing in the 1929 newspapers mentioned this controversy. Gavuzzi also claimed those many years later that Pyle had told him to keep the race close if he wanted to collect the winnings. That seems believable so get thousands to come and pay to watch the last day. Finally, Gavuzzi claimed that he ruptured his Achilles tendon on the next to last day, an obvious untruth given the racing he did shortly after that. Bunion Derby expert, Charles B. Kastner carefully examined all the evidence in his book, “The 1929 Bunion Derby” and concluded that Gavuzzi’s claims didn’t hold up. Others have believed Gavuzzi’s claims and conclude that Pyle wanted an American hero to win, and tried to rig the race in Salo’s favor at the end. Gavuzzi never felt any hard feelings against Salo, they remained good friends and respected rivals.

Pyle’s troubles

Would the runners get their winnings? A day after the race Pyle met with Salo in Pyle’s hotel room where he offered Salo $12,500 cash, right then, to meet his winner award. Salo refused to take “half a loaf,” would wait for the entire amount, but later would regret that decision. Pyle said publicly, untruthfully, that day that he was ahead of his race expenses. “The boys will get their money.”

Pyle’s troubles started to grow. After just two days, three runners who didn’t finish filed a complaint that they had not been returned money that Pyle promised to hold for them. Some girls in his “follies” road show also had a complaint filed against him along with a man still owed $400 for the 1928 race. A $3,121 suit was filed against him by the Southern Pacific for funds owed them to previously transport some football teams. More former employees came forward who were fired without cause along the way and were never given back pay.

Salo wanted to accept some endorsement offers and vaudeville performing offers, but for some reason Pyle nixed each of these trying to hold out for more money. The Lucky Strike tobacco company offered $1,000 for Salo to endorse their product, also a spring water company wanted his endorsement. The Erie railroad was starting a new fast line between New York and Chicago, wanting Salo involved and was going to name a Pullman car after him. Salo said, “I couldn’t accept any of these because Pyle stepped in. His contract with me tied me up so that I wouldn’t be able to earn a dollar without his consent, and the right share in the profits.”

By July, Pyle claimed he was penniless and that he had lost $100,000 on the race. The claims against Pyle were numerous and he had left many fired employees stranded along the way. At a hearing, he was given a tongue lashing. “These cases are not only serious ones, but they are disgraceful. It would appear that aside from any legal obligations, there are moral obligations involved here.” Pyle still claimed he would come up with the money owed. He was ordered to show is books but his auditor never appeared.

Pyle’s race idea did spread to Japan. In June 1929, ten young men started to race 400 miles in eight days from Osaka to Tokyo.

Six-day relay race in Los Angeles

On the evening of July 13, 1929, Salo and several other Pyle runners started competing in a 6-day (144 hour) relay race held at the American Legion Ascot Speedway. The race was staged by famed athlete, Jim Thorpe. Salo teamed up with Pyle runner, Sam Richman of New York. Eight other teams competed. After a day, Salo/Richman were leading the field. “The monotonous merry-go-round of the course mapped out in front of the grand stand appeared to be taking its toll on the runners as the troupe stumbled forward in the race trying for the record of 733 miles covered in six days and nights set by two French performers twenty-five years ago in New Orleans.”

At 127 hours, they had a 82-mile lead and had reached 650 miles, needing to average 5.1 mph the rest of the way to break the record. In the end, they did it. They won with 749 miles, winning by 107 miles.

Wicklund, Salo’s trainer said, “Johnny had to run better than he ever did before to break the record. His partner, Sam Richman, was badly handicapped with an infected heel. The brunt of the running fell on Johnny and he clearly showed that he is the greatest endurance runner in the world by the way he came through.”

Three months in California

Salo and his wife continued to remain in California making appearances. At times they were guests at Pyle’s “Red G” Ranch in Santa Rosa, California. Salo did fail to make an appearance promised at the Breakfast Club one morning that was attended by Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Gary Cooper, and others. Jim Thorpe announced intentions to take a group of the Pyle runners, including Salo, on a tour of county and state fairs to watch “the greatest troupe of athletes that have ever strutted their stuff.” This never materialized.

Near the end of August, Pyle surrendered to police as a defendant in two labor lawsuits. He reported that he was “dead broke.” Pyle was able to arrange for about $4,000 to be given to Salo and a promissory note for the remaining money.

Return home to New Jersey

Without his full winnings, Salo returned home to New Jersey in early September. He organized a 15-mile race with his Pyle runner pals, Andy Payne, Peter Gavuzzi, and Arthur Newton to be held on the Passaic high school track. They city arranged for $3,500 prize money with $2,000 going to the winner.

On race day, September 21, 1929, 3,000 fans came out to cheer their local hero. From the start, Payne jumped into the lead but then faded fast, seen to be out of shape. The group stayed together during the first mile which was reached in 5:41. Newton took the lead at the second mile “and his graceful, ground covering pace, soon pulled him far ahead. Newton lapped Salo on the 19th lap and continued on to win in 1:32 with Gavuzzi a half mile behind and Salo another quarter mile behind. It was said that “Salo appeared overweight and listless, but Salo’s finish was strong and he received a great ovation from the crowd despite the crushing defeat.”

Man vs. Horse

Just three days later, on September 24, 1929, Salo again took part in a six-day relay, this time pitted against horses and other men relays teams. The race was a two-man tag team race held indoors in Philadelphia. Salo was teamed up with Joie Ray (1894-1978), a taxi cab driver from Chicago who for many years was the top mile runner in America and ran in three Olympic games. Gavuzzi and Newton also ran along with many other Pyle runners.

The horses traveled on a “tanbark” track inside the cinder path used by the runners. The track was 12 laps per mile. The runners and horses alternated every four hours. The runners started with a pace of seven miles per hour. After six hours, Salo/Ray were in the lead with 51 miles. At 239 miles Gavuzzi/Newton pulled into a tie for 1st place. The horses were 12 miles behind. The race ended after 124 hours, at midnight on Saturday with Salo/Ray in 1st place with 523 miles, beating Gavuzzi/Newton by about a mile and a half. The lead horse team finished with 510 miles.

Passaic honors Salo

On October 2, 1929, Salo was officially welcomed home to Passaic at a reception held at the Capitol Theatre. He was presented with a scroll and a silver trophy of a runner mounted on a bronze stand. Salo said, pointing to the scroll, “I wouldn’t part with this for a million dollars. I want to thank everyone for the support given me during the race.” Gavuzzi and Newton were also present, introduced, and received a hearty applause. A few days later, Salo resumed his job with the police force.

On October 2, 1929, Salo was officially welcomed home to Passaic at a reception held at the Capitol Theatre. He was presented with a scroll and a silver trophy of a runner mounted on a bronze stand. Salo said, pointing to the scroll, “I wouldn’t part with this for a million dollars. I want to thank everyone for the support given me during the race.” Gavuzzi and Newton were also present, introduced, and received a hearty applause. A few days later, Salo resumed his job with the police force.

Salo was asked if he would ever get his Bunion Derby winnings. He replied “I have hopes. Pyle is a money maker. He is now dabbling in night clubs and the movies out on the west coast and he writes that someday he will make good all he owes me. I can only live and hope. In the meantime I am a policeman.” He still ran and was in relatively good shape

15-mile race in Montreal, Canada

As the Great Depression began raging across the world in 1930, race events for professional ultrarunners pretty much dried up in the United States. All professional sports suffered in America during that time. For a few years, promoters in Canada filled the void, and were able to attract some of the most talented American ultrarunners to head northward, to run in their races.

As the Great Depression began raging across the world in 1930, race events for professional ultrarunners pretty much dried up in the United States. All professional sports suffered in America during that time. For a few years, promoters in Canada filled the void, and were able to attract some of the most talented American ultrarunners to head northward, to run in their races.

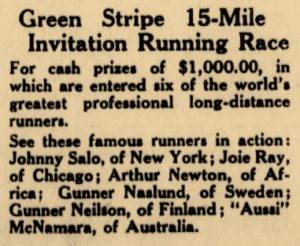

In February 1930, Salo went to Montreal to run in a 15-mile race which was associated with the finish of a long distance Quebec to Montreal Green Stripe snowshoe event that finished in the Montreal Forum. The 15-mile race was a double attraction. In the early stages of the race, Pyle runners, Newton and Abramowitz exchanged the lead. By mile twelve, Joie Ray, Salo’s former relay partner took control and sprinted ahead “with a tremendous burst of speed that resembled a 440-yard runner rather than a marathoner, and soon lapped the field.” Ray won with 1:41:50. Newton came in second, followed by Salo.

The 1930 Peter Dawson 500-mile relay

In July 1930, Salo returned to Canada to participate in a 500-mile relay, again teamed up with Joie Ray of Chicago. Many other Pyle runners also participated. The race involved teams of two runners each. “Unlike the man-killing Pyle 1928-29 marathon races across America which saw individual runners plodding along wearily the width of the continent, the Peter Dawson event will be raced in relays. The relay arrangement ensures more sustained and greater speed, a far more testing race.” The race was run in stages, for eight days. The details of this race can be found in a previous article The 1930 500-mile Peter Dawson Relay. Salo and Ray came in second place to Gavuzzi and Newton.

In July 1930, Salo returned to Canada to participate in a 500-mile relay, again teamed up with Joie Ray of Chicago. Many other Pyle runners also participated. The race involved teams of two runners each. “Unlike the man-killing Pyle 1928-29 marathon races across America which saw individual runners plodding along wearily the width of the continent, the Peter Dawson event will be raced in relays. The relay arrangement ensures more sustained and greater speed, a far more testing race.” The race was run in stages, for eight days. The details of this race can be found in a previous article The 1930 500-mile Peter Dawson Relay. Salo and Ray came in second place to Gavuzzi and Newton.

Policeman Salo on patrol

Salo used his running skills to again become a local hero when a mad dog attacked six people near a miniature golf course. The police were called in. “Officer Salo joined in the chase and finally cornered the dog in a back yard. Officer Crawbuck arrived with the net and dog was put in the patrol wagon and taken to headquarters”. On another day an insane naked man jumped from his third story window and fled down the street. Salo chased after the naked man for a half mile in a bizarre race. “Pedestrians were thrown into a turmoil.” The man finally slowed due to his injuries and Salo called for an ambulance.

The 1931 Peter Dawson 500-mile relay

In August 1931, Salo returned to Canada and again ran in the Peter Dawson 500-mile relay, this time teamed with Pyle runner Ed Gardner. Things didn’t go well and they finished in a a distant eighth place. Newton and Gavuzzi won for the second year in a row. It was rumored that Salo had been diagnosed with diabetes and that his health had deteriorated.

After this race, Salo hoped to run in a big snowshoe race held later in the winter also held in Canada.

Salo’s tragic death

On October 4, 1931, Salo was on police duty at a local exhibition baseball game at Third Ward Park. During the seventh inning, a crowd of fans started to surge onto the playing field along the third base line. Salo tried to get them to move back. The left fielder retrieved a hard hit ball and threw it toward third base on a perfect line, but Salo was in its path and was hit in the back of the head, near the right temple. He never saw it coming and fell to the ground unconscious for several minutes. He soon revived from first aid provided by players and spectators.The man who threw the ball, Ziggy Mayor demanded that Salo be taken to the hospital. Salo refused and resumed his duties. He was heard to say, “I’m not a quitter, I can take it.” Salo’s wife and children witnessed the hit and were just 100 feet away.

After the game as he was directing traffic, he was seen to begin to stagger. Two spectators dashed out to give him support and he collapsed in their arms. An ambulance was called and he was rushed to the hospital where he was in critical condition. He was attended to by several doctors who were consulting about the best course of action, but he never regained consciousness and passed away at 9:40 p.m. at the age of 38, with his family at his bedside. The cause of death was determined to be due to hemorrhage of the brain following a fractured skull. “Grief stricken Mrs. Salo was taken to her home after her husband had passed away, solaced by the presence of many kind friends”

“The news of Patrolman Salo’s untimely end cast a pall of gloom over the entire city, for he was exceedingly well-liked and was perhaps Passaic’s widest-known citizen. Salo’s body lay in state at his home and hundreds of admirers of the great runner came there to pay him tribute. All day long telegrams of condolence were received by Mrs. Salo coming from all parts of the United States.”

One of the telegrams was from C. C. Pyle. He pledged that he would still meet his debt, now to Mrs. Salo. He never came through on that promise. Flowers came from Gavuzzi and Newton. Salo’s relay partner, Joie Ray, came in from Chicago to pay his respects. More than 100 World War I veterans came to Salo’s home, four abreast to pay their last respects for Salo.

The next day a military escort brought Salo’s body to the funeral service at the First Presbyterian Church. “The funeral cortege passed between lines of thousands who lined the streets and were massed at before the church.” Leading the procession were Salo’s comrades of the Passaic Police Band.

The next day a military escort brought Salo’s body to the funeral service at the First Presbyterian Church. “The funeral cortege passed between lines of thousands who lined the streets and were massed at before the church.” Leading the procession were Salo’s comrades of the Passaic Police Band.

Two hours before the church service started, the building was filled to capacity. “So large was the throng that church officials had to notify the fire department to close the doors. Thousands unable to get within a block of the church stood outside with bared heads during the entire service.”

After the service, the police band played as the coffin was carried from the church and placed upon military wagon. Mrs. Salo was overcome with grief and fainted. She was revived and escorted to a waiting automobile. Kind people looked after and comforted her children, Leo and Helen.

After the service, the police band played as the coffin was carried from the church and placed upon military wagon. Mrs. Salo was overcome with grief and fainted. She was revived and escorted to a waiting automobile. Kind people looked after and comforted her children, Leo and Helen.

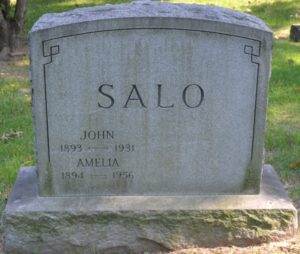

Thousands of school children lined Lexington avenue for several blocks. Several of his Bunion Derby friends with many war veterans and police, escorted his body to his last resting place at Cedar Lawn Cemetery. “There was no sprint at the finish. All that was mortal of one of the world’s greatest endurance runners was drawn along Lexington Avenue by six horses, animals he ‘ran into the ground’ not many months ago. The pace was slow.”

A firing squad of eight men fired three volleys as the silver casket carrying Salo’s body dressed, in his police uniform, was lowered into the grave and an old Army bugler played taps. A couple months later the American Legion gathered and placed a bronze marker on his grave. In 1998, his name was added to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington D.C.

A firing squad of eight men fired three volleys as the silver casket carrying Salo’s body dressed, in his police uniform, was lowered into the grave and an old Army bugler played taps. A couple months later the American Legion gathered and placed a bronze marker on his grave. In 1998, his name was added to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington D.C.

“Passaic has never before seen such a funeral. It showed how the world, in a rather soft day, appreciates strength and endurance, understands dogged courage, and admires simplicity of soul. Peace be with Johnny Salo.”

Passaic’s memory of Salo started to fade fast, but some cared deeply about his family. At first the police were only going to give Amelia Salo half of his pension, but they adjusted to a full pension. At first the city intended to tax Mrs. Salo on the promissory note, but people stepped in to make sure that didn’t happen. The full winnings were never received. Pyle continued with financial ruin. He had a devastating stroke and was never the same. He died in 1939.

Amelia Salo never remarried and raised her children as a single mother. She died in 1956. Son Leo played football in high school and daughter Helen was a cheerleader. In 1940 Helen married Everett J. Lotz Jr. and was a secretary. Leo married in 1945 to Edna “Joy” Mueller. At the time he was an air student at the Army Air Force Cadet Training Station in Douglas, Arizona. He died in 1970. John and Amelia had six grandchildren.

Salo’s running career and life were cut short. He was the greatest American ultrarunner of the first half of the 20th century. What would have happened if he had lived? Ultrarunning races dried up for all the Pyle runners during the great depression by 1932 and most of the American runners retired from the sport. Salo would have likely put it aside too, and would have continued to serve his community.

In 1982, ultrarunning pioneer Dan Brannen, of Philadelphia, remembered Salo. He held a 200-mile “Johnny Salo Memorial Road Race” from High Point, New Jersey to Cape May, New Jersey. An article about the race mentioned that Salo was North Jersey’s greatest single sports hero of the past century. His daughter, Helen was interviewed at that time and said, “My mother didn’t want him to race the second year. She felt it was too much for him.” She said that in Texas, near Mexico he got sick because of the water and his trainer told him to quit the race. “My father struck at him and said, ‘don’t ever say that to me again.’ Helen died in 1992. Johnny and Almelia Salo have quite a few great-grandchildren, some who are on Facebook.

Sources

- Mark Whitaker, Running for their Lives: The Extraordinary Story of Britain’s Greatest Ever Distance Runners

- Charles B. Kastner, The 1929 Bunion Derby: Johnny Salo and the Great Footrace Across America

- The Baltimore Sun, Apr 6, 1929

- The Richmond Item (Indiana), Feb 2, 1929, May 30, 1929

- The Morning Call (Paterson, New Jersey), Mar 18,23, Apr 2, 1929, Sep 6,9, Oct 8, 1929, Mar 12, 1930

- The Herald-News (Passaic, New Jersey), Mar-Aug, 1929

- The Daily News (Passaic, New Jersey), Mar-Oct, 1929

- The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), Mar 26, 1929

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), Apr 1, 1929

- The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), Apr 1, 1929

- Chillicothe Gazette (Ohio), Apr 16, 1929

- Daily News (New York, New York), Apr 21, 1929

- Casper Start-Tribune, May 30 1929

- The Daily Free Press (Carbondale, Illinois), Jun 28, 1929

- The Los Angeles Times, Jun-Jul, 1929

- The Havre Daily News (Montana), Jul 18, 1929

- Salt Lake Telegram, Jul 19, 1929

- The Boston Globe, Jul 20, 1929

- The Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), Jul 22, 1929

- The Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), Sep 23, 1929

- Pottsville Republican (Pennsylvania), Sep 24, 1929

- Times Colonist (Victoria, BC, Canada), Sep 25, 1929

- The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania), Sept 26, 1929

- The Billings Weekly Gazette (Montana), Sep 27, 1929

- Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), Sept 28, 1929

- The Guardian (London, England), Sep 30, 1929

- Daily Record (Morristown, New Jersey), Mar 17, 1982, Apr 11, 1992