Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:09 — 24.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]() Both a podcast and a full article

Both a podcast and a full article

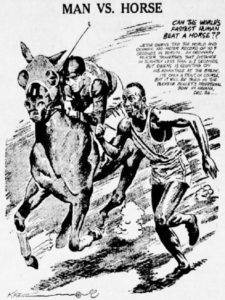

For more than two centuries, people have debated if humans on foot could beat horses. Those on the side of humans argued that over a long enough distance, human beings could outrun horses. It has been contended that humans are capable of covering vast distances after the horse becomes winded and unable to continue.

To try to prove this point, ultradistance races billed as “Man vs. Horse” were competed as early as 1879. But it was a 157-mile “man vs. horse” race held in Utah, in 1957-58. that captured the attention of America and beyond.

| Check out Davy Crockett’s new book, Strange Running Tales: When Ultrarunning was a Reality Show, https://ultrarunninghistory.com/strangetales/ |

19th Century

In 1818 at Feltham, Hertfordshire, England, a Mr. J Barnett, a long-distance runner “pedestrian” of Feltham, took on a bet for 200 guineas that he could beat a fast horse in a 48-hour race. The horse carried 168 pounds. The horse went out fast and reached 90 miles in 13 hours, stopping to feed only twice. After 24 hours, the score was horse: 118 miles, Barnett: 82 miles. After 48 hours the horse won, 179 miles to 158 miles. It was believed that the horse could have only gone a few more miles if the race was for another day.

In 1818 at Feltham, Hertfordshire, England, a Mr. J Barnett, a long-distance runner “pedestrian” of Feltham, took on a bet for 200 guineas that he could beat a fast horse in a 48-hour race. The horse carried 168 pounds. The horse went out fast and reached 90 miles in 13 hours, stopping to feed only twice. After 24 hours, the score was horse: 118 miles, Barnett: 82 miles. After 48 hours the horse won, 179 miles to 158 miles. It was believed that the horse could have only gone a few more miles if the race was for another day.

Shorter races involving a steeple chase were competed too. In 1840 at Hyde Park in Sheffield, England, a match was conducted between a Mr. Cootes and an old hunting horse, “George IV.” Along the way the two were required to leap over hurdles four feet high. “Cootes took the lead at starting, but the horse refused the first leap and could not get along. The biped continued to increase his lead, the horse repeatedly refusing the hurdles. In the eleventh round, and at the 55th leap, horse gave in, after which Cootes had the race to himself, and won as he liked.”

In 1855, a unique race was conducted in Paris, France. A Spaniard, Genaro, was pitted against thirteen English racehorses. The rules for this race required the horses to constantly run or trot. If a horse started to walk, they were out. Genaro could run or walk. The race was limited to seven hours and the person or horse to go the furthest distance was the winner. Laps were made around a large circus area, about a mile and a half. All but two horses gave up before Genaro was tired and quit. He had covered about 46 miles and the two horses, about 60 miles.

It was clear to the public of that era that horses could easily beat runners at short distances. For entertainment there were many events where they established handicaps to make it more competitive. In 1857 a race was held in Rochester, New York pitting Charles Curtis against a famous horse, Frank Hayes. The horse needed to run three miles against Churtis’ one mile. The horse completed miles in 2:53 and 2:48, but Curtis won with a mile time of 8:42, winning by two seconds, “admid the tremendous cheers of the large concourse of people present on the track to witness the feat.”

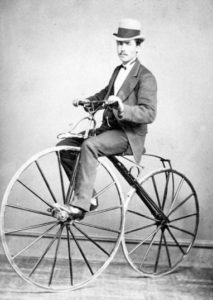

By 1869, contests that pitted men on early bicycles against horses were being held. On May 11, 1869 at Riverside Park in Boston, Massachusetts, Walter Brown, a talented oarsman, riding a velocipede raced against a horse John Stewart. A month earlier Brown had amazed the country by riding his primitive bike 50 miles in four hours. In this race, Brown had to cover three miles to the horse’s five miles. Brown won in 26:20. The horse completed nine miles in 26:35.

By 1869, contests that pitted men on early bicycles against horses were being held. On May 11, 1869 at Riverside Park in Boston, Massachusetts, Walter Brown, a talented oarsman, riding a velocipede raced against a horse John Stewart. A month earlier Brown had amazed the country by riding his primitive bike 50 miles in four hours. In this race, Brown had to cover three miles to the horse’s five miles. Brown won in 26:20. The horse completed nine miles in 26:35.

In 1878, the endurance aspects of humans vs. horses again surfaced in newspapers. In Holmes Ohio, a man wagered he could walk further in a week than a horse ridden by a farmer. The results are unknown, but a debate resulted. “It is affirmed that a man’s powers of endurance are superior to those of a horse. The question is one of endurance, not rapidity of gait. Properly tested, the man would probably be found to be superior.”

In January 1879, George W. Guyon (1853-1933) originally from Canada, living in Chicago, Illinois, an elite pedestrian, and later the 6-day world champion that year, raced against a stallion, Hesing Jr. for 52 hours in Chicago. Guyon reached 149 miles, but the horse covered 201 miles despite the small track in the Exposition Building with sharp turns. The Chicago Tribune stated, “It was the first time in a long journey that a horse had defeated a man.” The horse took long rests totaling 24.5 hours. Reasons given for Guyon’s defeat was that he wasn’t feeling well and “the cold air of the building affected him to such an extent that during the last 24 hours of the contest he was unable to do himself justice.”

Later in 1879 two of the greatest pedestrians in history, Edward Payson Weston (1839–1929) and Daniel O’Leary (1841-1933) discussed the previous event and speculated how a man would do against a horse in a 6-day event. They disagreed on this subject. O’Leary believed that horses would win, Weston was on the side of humans. To settle the debate, a race was held in San Francisco beginning on October 15, 1879, with seven men against eleven horses on a track at Mechanics’ Pavilion. A horse named Pinafore won with 557 miles, but there were no truly elite runners/walkers in the event.

Later in 1879 two of the greatest pedestrians in history, Edward Payson Weston (1839–1929) and Daniel O’Leary (1841-1933) discussed the previous event and speculated how a man would do against a horse in a 6-day event. They disagreed on this subject. O’Leary believed that horses would win, Weston was on the side of humans. To settle the debate, a race was held in San Francisco beginning on October 15, 1879, with seven men against eleven horses on a track at Mechanics’ Pavilion. A horse named Pinafore won with 557 miles, but there were no truly elite runners/walkers in the event.

Weston was still unconvinced, so O’Leary put on another 6.5-day event in Chicago starting on September 5, 1880. It was held at the Haverly tent on the lake shore and included prize money of $3,000. Fifteen men and five horses competed. There was a crowd of four thousand spectators on hand for the first day. The runners started off on a six-minute-mile pace and the horses were clocking eight-minute-miles early on. After the first day the leading horse had reached 130 miles and the leading man, 117. When 48-hours was reached, the top horse, Speculator, had reached 220 miles. The top man was at 195 miles, but he would quit at 200 miles with a swollen face.

Five days in, Daniel Byrnes, age 21, of Elmira New York, took the lead. On the last day Speculator had regained the lead but sadly died while resting in his stable. Byrne also suffered during the later stages. “He began to bleed at the nose and fell down in a fainting fit and was carried into the tent amid a chorus of ‘ohs’ from the ladies. It took half an hour to revive him, and when he came out again he had lost five miles besides being very stiff and sore.” The leading horse was a black mare named Betsy Baker. She “failed to respond to the whip” and went in for two hours before she could come out again. She had finally responded to a “dose of champagne.” But after that she could do no more than a slow walk. Byrne won, covering 578 miles in the 6.5 days. Betsy Baker finished in second with 563 miles. One horse died as a result of the race.

The Chicago Tribune stated, “That it was a genuine feat of endurance, as between the parties to the race, no one who witnessed it will doubt. Both horses and men were sent for all they were worth, and that the horses, after leading for over four days, suddenly began to fall away because they could not be made to go any faster, for all available means to urge them forward were employed.” Edward S Sears, in his book, “Running Through the Ages” concluded, “The race did not prove men could always beat horses at multi-day racing, but it did show that horses were prone to dropping dead from exhaustion or overheating in long races where healthy humans were not.” During the event the Illinois Human Society caused the arrest of a man on charges of cruelty to animals and after the event warrants were also issued for five other men.

During February 1894, a fifty-hour race was conducted in Paris, France between a Belgian, Gallot, on foot against a jockey Cody, who could use two horses. Gallot reached 151 miles compared to Cody’s relay of horses who reached 160 miles. “In the last half hour, Cody changed horses every two laps to the disgust of the onlookers, several of whom were expelled from the building for pelting him.”

Woman vs Horse

Did woman pedestrians race against horses. No matches have been found, but in August 1880, Lizzie Baymer the champion bicyclist of the Pacific Coast, raced against a horse on a bicycle at Sacramento, California at Agricultural Park in a three-hour contest. In 1885, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Elsa Von Blumen rode against a horse named, Lady Pond Dexter. She ran a mile to the horses’ mile and a half. The horse won by 100 feet.

In 1908 a similar contest was conducted as the woman world’s champion, Fraviola (real name, Belle Norton) competed against two horses in a three-hour race at Cincinnati, Ohio. “She made the first mile in three minutes, but the horse was under the wire an easy winner.” The race was hard for Fraviola because of the rough dirt track. She had to peddle around the outside of the track as the horses used the inside line. The organizer changed the terms of the race, and new heats were conducted where Fraviola was given a handicap, requiring the horses to go twice as far. Fraviola won the remaining heats as the horses began to tire. The male cyclists of the era also competed against horses in races of various length and usually fared well, coming out as the victors.

Early 20th Century

In 1927 an elite young runner of that era, Paul “Hardrock” Simpson (1904-1978), raced against a Texas pony on a 500-mile course from Burlington to Morehead City, North Carolina and back. A large ceremony sent the two racers off. At Raleigh kids chased Hardrock and threw rocks at him. Accounts about the finish vary and really changed as Hardrock’s legend grew. The true story is that at about mile 145, a doctor determined that Hardrock’s foot was infected and that he needed to stop. He did. The horse was in poor shape too, five miles ahead of him. They both stopped. Hardrock did not win and was not awarded $500. The legend that was later told was that Hardrock stopped when he learned that the horse dropped dead 25 miles behind him, and he won the $500. This is not true. It is amazing how legendary stories change and grow over the years.

In Sept 1929 at Philadelphia, a six-day race was conducted to answer the question yet again: “In an endurance race would a man beat a horse?” The race was held at the Philadelphia Arena with five two-men teams and the same number of horse teams that ran alternate hours. The runners included some of the greatest ultrarunners of that era including, Peter Gavuzzi of England, Arthur Newton of South Africa, and Johnny Salo of the United States.

In Sept 1929 at Philadelphia, a six-day race was conducted to answer the question yet again: “In an endurance race would a man beat a horse?” The race was held at the Philadelphia Arena with five two-men teams and the same number of horse teams that ran alternate hours. The runners included some of the greatest ultrarunners of that era including, Peter Gavuzzi of England, Arthur Newton of South Africa, and Johnny Salo of the United States.

The horses ran on a “tanbark ring” and the men ran on a boarded track inside that ring. In this case, the men took the early lead after two hours, 18 miles to 14 for the horses. After 26 hours they were still leading with 144 miles to 122. But on day 4 and day 5 the horses took a lead. The horses evidently were getting bored with going in circles on the small indoor track and would continually slow to a walk despite their jockeys’ efforts to push them into a trot. Finally, they refused to trot. The horses were replaced (unknown to the spectators) but eventually the new horses also slowed to a walk. The original horses were brought back, but by then the runners had a firm lead. Johnny Salo and Joie Ray won with 523 miles and were about 13 miles ahead of the horse team.

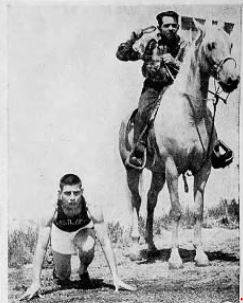

In 1929 at a huge rodeo at Roswell, New Mexico, Flying Eagle, a 34-year-old Hopi Indian runner ran in a 100-mile race against a horse on an oval track. He was one of the best and famous Hopi runners of the time and had helped in the search for a downed airliner “City of San Francisco” with eight aboard in the mesas of New Mexico. Charles Lindbergh also helped with the historic search.

The 100-mile race against the horse started at 4 a.m., but on this day, the horse was the victor. Only once was Flying Eagle in the lead when the horse was brought in for a rest. At mile 43, after nine hours, Flying Eagle was five miles behind the nine-year-old mustang, “Boss.” At that point Flying Eagle fell exhausted on the dirt track and was taken to an emergency hospital. Boss was “lathery and showed signs of fatigue” but its owner believed he could have completed the 100-miles if necessary.

Circus, Carnivals, and Stunts

Over the years various “man vs. horse” acts were part of circuses and carnivals for short distances or strength contests. P.T. Barnum of circus fame would stage a man against a horse. The man would run one mile, while the horse ran two miles. Under the circus tent, a 350-yard course was used around the rings, it was pretty much a staged act. “In each race the horse started about seven lengths behind the human runners and the jockey was instructed to slow the horse in the stretch, if necessary, in order to make sure that one or the other of the two foot racers was first under the wire. This made the race unusual, which it wouldn’t have been had the horse beaten the men.” The runners would draw straws to see who would win each race. In the 1930s, two professional runners did this act twice a day for two weeks and lost several pounds. They decided to start “loafing” until the finish. When they began to loaf, the horse came up behind them, breathing hard on their necks. “That scared us. The jockey used to holler at us, ‘Go on you pair of mud turtles, or I’ll climb up your back.’ Then we had to run.” After three weeks they were “cooked” and just couldn’t take it anymore. The next night they faked injury at the first turn and limped off to the dressing room. They were fired and the manager said, “You’re just a couple of bums. I’m going to put an ostrich in your place to run against that horse.”

In 1936 at Havana, Cuba, Olympic champion Jesse Owens (1913-1980) ran against a horse in the 100-yard dash. Well, actually the horse had to run 140 yards and Owens just 100. Owens ran in 9.9 seconds and won by 15-20 yards. It was his first race as a professional enabling him to be paid for the event. He commented, “People said it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do? I have four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.”

Another race in the 1930s “saw a foot runner pitted against a thoroughbred on a tiny 18-laps-to-the mile course. The human won because the horse went wide at all the sharp turns and finally got so dizzy it was no contest.”

In 1940 in Summerville, South Carolina, Dr. Arne Suominen, originally of Finland, wanted to test his running ability against a horse in a 40-mile race. He set up a course for this solo event that would be out on the road and conclude with 13 miles around a track. The trainer of the horse used a run/walk strategy for the horse. It would trot for eight minutes and then walk four minutes. The horse took the early lead, but the doctor went ahead at the three-mile mark. They exchanged the lead for the next seven miles. Suominen took many walking breaks and drank orange juice. When they reached the track stage, the horse was less than a mile ahead, but Suominen complained of bad blistered feet, so he removed his shoes, running barefoot. This didn’t help much and when he was two miles behind the horse with 5.5 miles to go, he quit and conceded victory to the horse.

Canada Six-day

In 1941 in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, Robert Bower raced against a horse in a six-day event on a half-mile track. It was a close race but on the fourth day, Bower withdrew withdrew because of a sore toe.

1943 Event in Southeastern Utah

The man vs. horse debate heated up in rural Utah during 1943. “For years the argument whether man can out-endure a horse in the long run had raged in and about Douglas Galbraith’s general store at Blanding, Utah. Galbraith (1893-1988) stood up for the man’s superior powers of endurance, but many a stockman spoke up in favor of the horse.” A “man vs horse” event that they thought was the first of its kind in the nation, was set up and hundreds of dollars of bets were put on the line. Leland Shumway (age 27) (1915-2000) a miner, was chosen as the runner and a horse named Zebs would be the four-foot contestant. The contest was a 24-hour, fixed time event on a rural highway between Blanding and Bluff, Utah, near the four-corners region. It was described as “a lonesome road running through a fantastic country gashed with canyons and dotted with sage, all but uninhabited. Its dips and turns on the way down to the Arizona border are so pronounced it is referred to in guidebooks as American’s ‘last adventure road.’” The contestants would go back and forth on the 26-mile stretch of road, trying to pile up as many miles as they could in 24 hours.

Soon after the start, Zebs pulled ahead of Shumway, who had not done any specific training for this race. Zebs covered the first 52-mile lap back to Blanding in less than seven hours. Poor Shumway was still near Bluff about 25 miles behind. After a total of 15.5 hours, as Shumway was nearing Blanding, Zebs lapped him, reaching 104 miles. Shumway ate and rested at Blanding and then continued. Six miles later his legs were so stiff that he had to stop for an extended rest. Word came to him that Zebs was also having problems and was near collapse. This motivated Shumway to continue. But Zebs recovered, made it to Bluff for the third time and continued. Shumway quit after 20 hours, covering only 60 miles. Zebs covered 140 miles in 24 hours. It is uncertain if Zebs always had a rider on board.

This event didn’t really settle the debate. Shumway said, “The radio says that I said I was licked. But I’m not convinced.” Folks in Blanding pointed out that if Shumway would have trained for the race he could have run further and probably could have won.

Oregon’s Man vs. Horse Craze

In 1947 Oregon became interested in Man vs. Horse events. First it was a highly publicized tug-a-war in Waterloo, south of Salem. The horse won in about 30 seconds. In 1949, at Lebanon Meadows, Paul Smith of Portland (age 64) challenged a horse in a walking-only content for 75 miles on a half-mile oval track. Smith had finished the famous 1928 Bunion Derby (trans-continental) race in 17th place. The racers were away in a chilly stiff 15 mph wind, early in the morning. Smith always ate as he walked and just paused briefly now and then for a swig of ice water, lemon soda or hot coffee. The horse was taken off the track twice for oats and a brisk rub-down. But over the day, the horse averaged about one mile per hour better and reached 75 miles in 14:40. Smith reached 61 miles in that time. He said, “On a hundred mile course, I know I could outlast any horse. I’d like to take him on a longer test.” Salem High School even got into the act in 1949 when the captain of the track team raced 100 yards against a horse.

In 1947 Oregon became interested in Man vs. Horse events. First it was a highly publicized tug-a-war in Waterloo, south of Salem. The horse won in about 30 seconds. In 1949, at Lebanon Meadows, Paul Smith of Portland (age 64) challenged a horse in a walking-only content for 75 miles on a half-mile oval track. Smith had finished the famous 1928 Bunion Derby (trans-continental) race in 17th place. The racers were away in a chilly stiff 15 mph wind, early in the morning. Smith always ate as he walked and just paused briefly now and then for a swig of ice water, lemon soda or hot coffee. The horse was taken off the track twice for oats and a brisk rub-down. But over the day, the horse averaged about one mile per hour better and reached 75 miles in 14:40. Smith reached 61 miles in that time. He said, “On a hundred mile course, I know I could outlast any horse. I’d like to take him on a longer test.” Salem High School even got into the act in 1949 when the captain of the track team raced 100 yards against a horse.

Utah’s 1957 Man vs. Horse 157-mile race

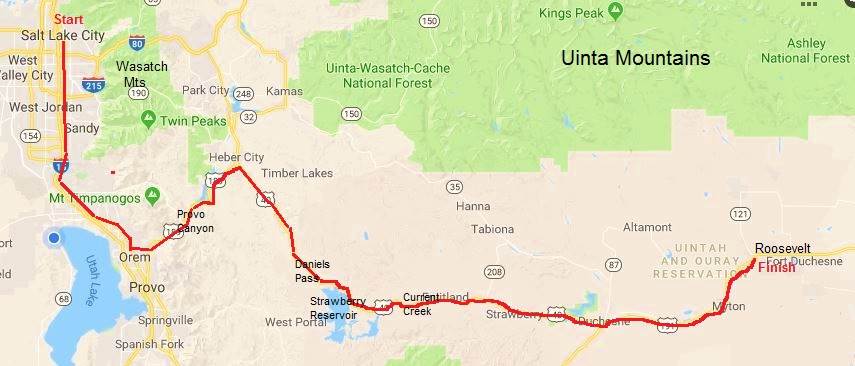

In 1957 the country turned its attention to rural Utah “to pit endurance against speed,” men against horses. The 1957 contest was between two men and two horses from downtown Salt Lake City, to the rural ranching/oil town of Roosevelt, in eastern Utah, a distance of about 157 miles. The course went south, up Provo Canyon to Heber City and then on Highway 40 to Roosevelt. It started at 4,300 feet and reached as high as 8,000 feet at Daniels Pass.

The runners chosen for this race were elite college distance runners on the Brigham Young University (BYU) track team. They were Albert Ray (age 24) of St. Albans, New York, and Terry Jensen (age 18) of Idaho Falls, Idaho. Ray was confident. “I think we’ll beat them. The asphalt will be murder on the horses’ feet.”

BYU track coach, Clarence Robison (1923-2006), who ran BYU track in 1948 and went to the London Olympics that year, predicted that his runners would win in 30-36 hours on the all-pavement course. He said that if the course was instead less than 75 miles, the horse probably could win, but beyond that the advantage leans toward humans who have greater recuperative powers. He also pointed out that the runners could eat and drink on the run.

The riders were Roy Hatch (age 71) (1881-1959), a rancher, and Ray Hall (age 18) (1939-1988), an oil worker, both of Roosevelt. Hatch rode a 6-year-old thoroughbred-quarter horse. Hall rode a small 11-year-old wild Mustang that he had caught two years earlier and trained for the race.

The race was sponsored by the Roosevelt Bullberry Boys Booster Club and part of a “Days of 1906” celebration marking the opening of the nearby Ute-Ouray Indian reservation and the settling of Roosevelt, Utah. The club was led by Lynn Whitlock who contacted many television and radio networks about the event, putting the little town of Roosevelt on the nation’s map. Stories were published as far away as Venezuela and Panama.

The race started on South Temple Street in downtown Salt Lake City near the Brigham Young monument on November 15, 1957. The contestants first paraded through downtown for five blocks where a ribbon was cut by the city mayor, and the sheriff fired a gun to officially start race. Jeeps pulling trailers were provided as crew vehicles. Light snow fell, and the forecast was for snowy weather during the race. The tracksters wore blue sweat suits and their heads were covered with woolen khaki covering with only their eyes and noses exposed to protect them from the cold.

Betting was part of the event. With one dollar, a person could put in a winning time prediction with the hope of winning a $500 U.S. Savings bond. Profits went to a new rodeo arena for Roosevelt.

After about two hours they were in nearby Sandy. The runners were about 1.5 miles ahead of the horses. BYU track coach Robison drove along with the runners crewing them. A BYU professor in the health education department had tests performed on the runners during the race including electrocardiograms, blood tests, and urinalyses. He said, “it isn’t very often that we have an opportunity to study body functions of a man who has run 100 miles.”

That night, runner Jensen dropped out about the 55-mile mark along the Deer Creek reservoir up Provo Canyon due to a tight leg tendon. The other runner, Ray slept for about 2.5 hours during the early morning at about the 70-mile mark in Heber City and was in excellent condition. The horses had the lead and were re-shoed. As for the human shoes, Ray tried various shoes to help his feet. One pair were shoe used by marathoners with thin soles but with “rippled rubber” lugs were added. This type of shoe was developed for paratroopers “to lessen the shock of hitting the ground.”

Ray reached the 100-mile mark in about 35 hours. Coach Robison ran along pacing him at times during the second night. At about mile 110, with about 48 miles to go, Ray rested for 90 minutes at Current Creek, but shortly thereafter gave up the race because he was hobbling on swollen ankles. He was clearly under-trained for ultradistances. He said, “I caught up with the horses at Current Creek and felt fine except for my feet and ankles. I was forced to quit because the doctors were afraid that blood poisoning was starting to develop in the legs.” Ray was later taken to the hospital in Roosevelt, and then transferred to the BYU health center and treated for his swollen ankles. Ray said, “I’ll be back again.”

The two horses ridden by Hatch and Hall went on together, eventually trotted down main street in Roosevelt, and broke a ribbon that stretched across an intersection to the cheers of more than 6,000 people. They finished in a very slow time of 57:15. Their actual riding time was 32:15. At times the horses were so exhausted that they refused to eat. Hatch said “I never had such a thrill as when someone from Salt Lake City called me Roy Rogers. The only thing is, I don’t think Trigger could have made the run.”

The winner of the $500 Savings bond was a man from Orem Utah who guessed the finishing time within about 11 minutes.

A few months later in 1958, a Utah editorial was critical of the race and plans for a second race that year. “The man vs. horse race is a nice publicity stunt. However, over the Salt Lake to Roosevelt course it proves little—except that both horse and man get lame pounding the paved roads.”

Utah’s 1958 Man vs. Horse 157-mile race

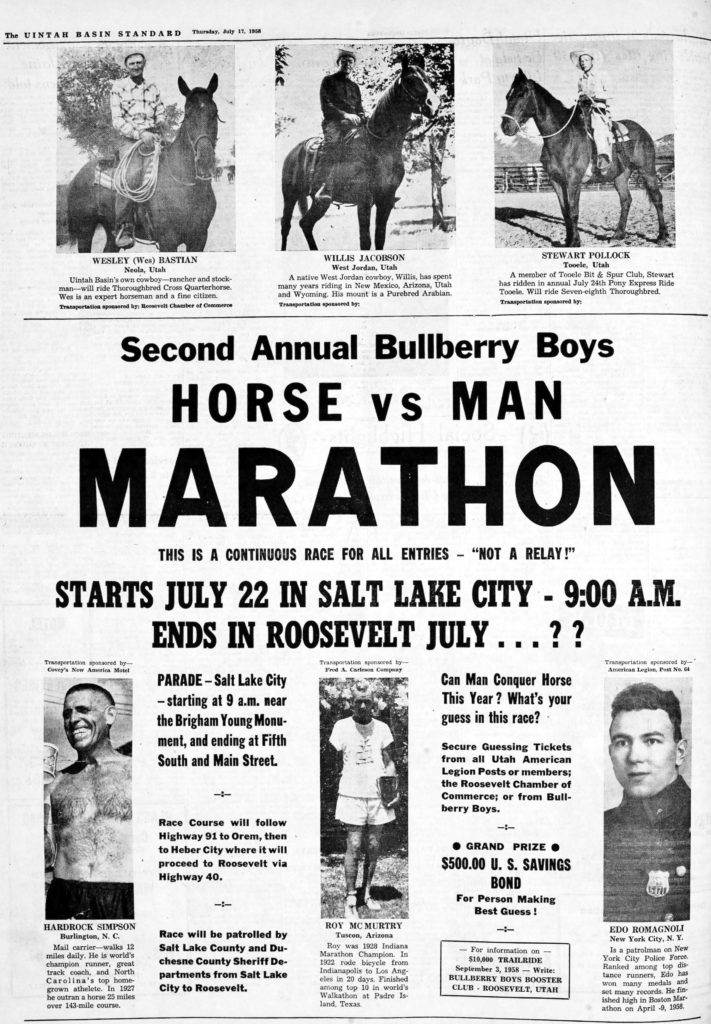

The 1958 event was planned for July 22, 1958. Thirty-five runners applied to participate. Three were selected. The runners were all professionals and included Paul “Hardrock” Simpson (age 53) (1904-1978) a mailman from Burlington, North Carolina. Simpson was a 1929 Bunion Derby (trans-USA) finisher who also raced against a horse in 1927. Also running was Edo Romagnoli (age 37), a New York City policeman who had won multiple marathons. The final runner in the threesome was the famous one-armed runner, Roy McMurtry (age 62) of Tucson, Arizona who had also walked the Padre Island Walkathon in Texas. In 1922 he rode a bicycle from Indianapolis to Los Angeles in 20 days.

The 1958 event was planned for July 22, 1958. Thirty-five runners applied to participate. Three were selected. The runners were all professionals and included Paul “Hardrock” Simpson (age 53) (1904-1978) a mailman from Burlington, North Carolina. Simpson was a 1929 Bunion Derby (trans-USA) finisher who also raced against a horse in 1927. Also running was Edo Romagnoli (age 37), a New York City policeman who had won multiple marathons. The final runner in the threesome was the famous one-armed runner, Roy McMurtry (age 62) of Tucson, Arizona who had also walked the Padre Island Walkathon in Texas. In 1922 he rode a bicycle from Indianapolis to Los Angeles in 20 days.

The horsemen were Willis Jacobsen (age 61) of West Jordan, Utah on an Arabian stallion, Keith Bastian (age 21), who substituted for his father, of Neola, Utah on a thoroughbred quarter horse, and University of Utah student, Stewart Paulick (age 24), of Tooele, Utah, riding on a thoroughbred, Dodger.

Jeeps pulling trailers were again provided for each participant to carry food and medical supplies, and provide a resting place for runners and riders.

A masked “mystery” rider known as “The Bat,” who wasn’t entered in the race, showed up at the start. He was clothed in a black flowing robe and helmet. “The Bat” rode up on a “skittish” cow pony painted with white circles. He was an unwelcome participant and organizer Lynn Whitlock said, “When he gets to Roosevelt, we’ll rip that mask right off.” The “Bat” didn’t say a word at the start. “The rimless spectacles perched outside the mask glinting over its eye holes.”

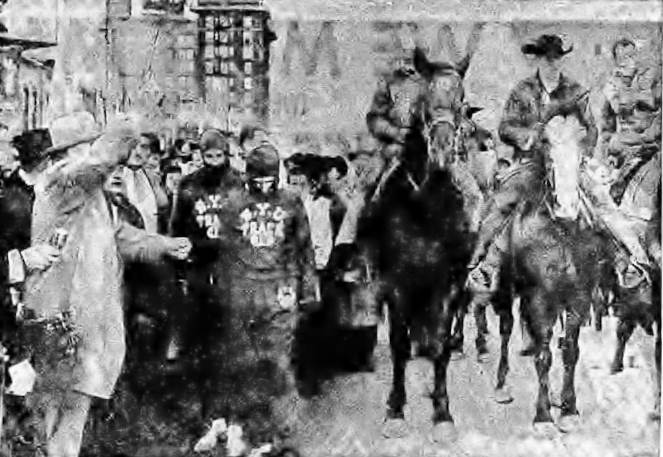

Before the actual start, the participants paraded five blocks in downtown Salt Lake City led by native Americans from the Ute and Ouray reservation, performing tribal dances at the middle of each block and at each intersection.

A kid, Val Sharp, on a long-distance bike, also joined the procession just south of Salt Lake City and tagged along for another 50 miles before pooping out at Heber. “The tourists piled up behind the riders and runners as they headed east from Orem, abandoning four-lane for two-lane pavement. For all of it, they were patient, if somewhat bewildered. Hardly a horn honked and sheriff’s deputies shepherding the caravan waved them by at every wide spot of the road.”

Runner, Romagnoli, led the race for the first few hours but then was overtaken by “The Bat.” McMurtry made it to about mile 25, dropping out three miles north of Lehi. He said, “I had cramps in my leg and they seemed to get worse all the time. This’ll be my last run. At 62 I think I’m just a bit too old.”

In Orem, Hardrock Simpson’s escort Jeep missed the turn toward Provo Canyon and led him four miles out of his way into Provo. When the mistake was discovered, the Jeep driver tried to convince Simpson to take a ride back to the missed turn, but Simpson refused to take a ride and ran back to the mistake point, running a total of eight “bonus miles.”

It was 90 degrees as they made their way up Provo Canyon and they were scattered across ten miles. At the junction in Heber to turn onto Highway 40, there were about 3,000 spectators cheering the racers.

That evening, Romagnoli took a two-hour rest stop in Heber. He vowed, “I’ll go on ‘till I fall on my face.” He was treated like a hero “through towns along the race route and drew cheers and applause. Patrons of a café in Heber City, where he stopped for two glasses of water Tuesday night, rose and applauded as he entered.”

“The Bat” dropped out about mile 85 at Strawberry Reservoir. His horse was exhausted, and it refused to go further. (“The Bat” was later identified as Kenneth Higley (1925-2006), of Salt Lake City. He was a World War II veteran pilot and was age 32 at the time with a wife and several children).

Paulick took over the lead as his horse, Dodger had renewed strength. Paulick explained, “He started running like he usually does and that’s when we made our time.” When Romagnoli reached the high point of the course, Daniels Summit, near Strawberry Reservoir, there were no hot drinks there as he had expected, and he was chilled for the rest of the night. He said, “Even though it was all downhill, my legs were chilled, and aching and I couldn’t run.”

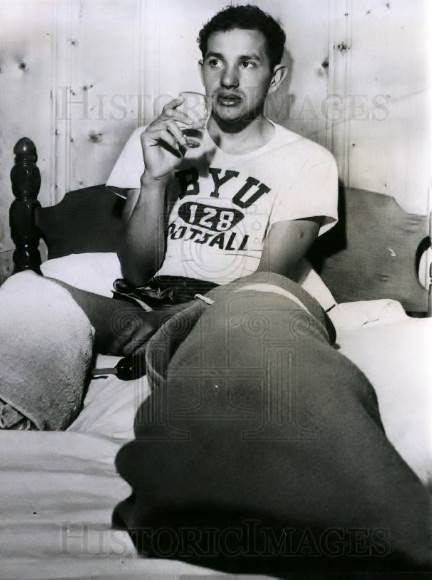

Romagnoli, far ahead of the other runners, made it down from Strawberry Reservoir and hit the 100-mile mark at 21:22 which that year was the fastest known time for 100 miles in the modern (post-war) American ultrarunning era. He continued and about 6 a.m., at Currant Creek, he was treated to a hot bath. A small cup of blood was drawn from blood blisters beneath two toenails. (He later lost six toenails.) The bath seemed to hurt more than help because it drained his remaining strength. He said, “I could feel it coming and knew after two miles I didn’t have any bounce and wouldn’t be able to finish.” He dropped out at about mile 118 because of severe cramping and at the recommendation of a doctor. At the time, he was only about two miles behind the leading horse (Paulick on Dodger) and well ahead of the other remaining horse and runner in the race.

For the last 20 miles of the race, driving rain pounded the leader, Paulick on Dodger. It was the first rain in that area in 2 ½ months.

Paulick entered the little town of Roosevelt, cheered by about 2,000 people jamming Main Street, and finished on Dodger in 29:33:40, beating the remaining runner, Simpson, by 57 miles. During his ride, Paulick made six rest stops totaling about three and a half hours. He reported that he had stiff legs and was eager to get into dry clothes. Paulick said that Dodger trotted about 90 percent of the time. Dodger was ready to drop at the finish but was quickly led off for feed, water, and a rub down. (The vets would declare the next day that he was in sound condition. In 2018, Joseph Stewart Paulick was 84 years old and still living in Tooele, Utah).

Race organizer, Whitlock proclaimed, “Horses have proven, for the second time in less than a year that man is no match in a long race.” Romagnoli, who as the finish line, agreed that “man will invariably come in second in an endurance race. Everyone knows a horse can run faster than a man, but the theory was that the horse would wear out over a prolonged route, but they don’t.” Romagnoli also said, “I don’t think anyone ever ran 100 miles like that before. You could go all over the world and not find a course as rough as that. I made a good race while I was in it.”

Whitlock announced that this race was the last “Man vs Horse” race to be put on by his group. “After a race using amateur runners and one using professional runners, we feel it has been decided definitely that a horse can outrun a man over a 157-mile course.” (A 1959 race was held on the same course, but between men and women riders. Dorothy Luck covered the 157-mile course in just over 16 hours on her thoroughbred horse.

After Paulick finished, Simpson, at mile 100, was told the race was over and that he needed to stop. Simpson vowed he wouldn’t quit until he reached Roosevelt. Officials ordered the removal of his escort jeep and formally declared the race was finished. But Simpson continued to run, with his wife driving along in a station wagon. A few hours later, as evening arrived, Simpson decided to quit after reaching 118 miles, stopping at the same point that Romagnoli had reached. Rider, Willis Jacobsen also continued. He managed to finish at Roosevelt during the night about ten hours after Paulick, in about 39 hours.

A few weeks later Edo Romagnoli was on the TV program, “To Tell the Truth” to pick the right person who ran against the horses. In 2018, Romagnoli was 97 years old and still living in New York.

In October 1959, Alva Leroy Hatch, a horseman finisher of the 1957 race went missing on a scheduled bus trip from Long Beach, California, to Durango, Colorado. His body was found four months later near Farmington New Mexico. Family members said that 73-year-old Hatch liked to “roam around and prospect.” They believed that he experienced a heart attack. Foul play was ruled out.

Montana Race

After these successful events, a similar race was staged in Missoula, Montana, in 1960. Former Montana State University track star, Bill Anderson who held the school record for the 880, ran against a horse in a 72-mile uphill distance race from Missoula to Polson. It was part of the city of Polson’s founding celebration. Anderson “Andy” was confident. “Seventy-two miles actually isn’t a long distance for a man. But I seriously doubt if the horse can finish.” He predicted that he would win in about 12 hours.

After the start, the horse, Little Joe, took a fast lead. Anderson kept a fast pace for the first 16 miles but slowed on a tough climb. At Arlee, a crowd of spectators lined the road. Little Joe was about five miles ahead of Anderson at this point, the marathon mark. In Arlee, Anderson ate bits of beef and sipped liquid as his legs were massaged by trainers from MSU athletic department to get out the knots in his muscles. One of his legs had been wrapped against cramps fairly early in the race. Soon the other had to be wrapped. Anderson blamed a cold rain for his cramps and swollen knees.

Anderson only lasted six hours and 37 miles because of the leg cramps. The horse, Little Joe, was a couple hours ahead of Anderson when he quit. This was yet another example of a college track star who had no idea how to train for ultradistances. The horse went on to finish in 12:20.

Man vs. Horse Marathon

In more recent times, “Man vs. Horse” for ultradistances have run its course as there is more attention put into caring for horses in endurance events. There still are such races at shorter distances. For example, in 1980 the Man vs. Horse Marathon was established in Wales, with a distance of about 24 miles and more than 4,500 feet of climbing. It is still held today (2018) and was established as most of these races were, to settle a debate between two people. In the race’s history, there have only been two human champions.

Arizona’s Man Against Horse

In 1983, a Man Against Horse race was established near Prescott, Arizona. It was a two-day 60-mile event, 30 each day. Runners, cyclists, and horses were invited. It was put on by the Prescott Police Athletic League. In 1985, two runners finished just 50 minutes behind a horse. The horses had won each of the first three years of the race. The course was tough in 1985. One runner said, “I could have used a rope out there on some of the climbs.” Weather played a role each year with snow, rain, and mud. Eventually the event was changed to a one-day event with various distances including a 50-mile race.

In 1983, a Man Against Horse race was established near Prescott, Arizona. It was a two-day 60-mile event, 30 each day. Runners, cyclists, and horses were invited. It was put on by the Prescott Police Athletic League. In 1985, two runners finished just 50 minutes behind a horse. The horses had won each of the first three years of the race. The course was tough in 1985. One runner said, “I could have used a rope out there on some of the climbs.” Weather played a role each year with snow, rain, and mud. Eventually the event was changed to a one-day event with various distances including a 50-mile race.

In 2019, Nick Coury of Arizona became the first runner to beat the horses in the history of this race. He finished the 50 miles in 6:14. The horses were required to stop at three vet checkpoints and rest for a total of 75 mandatory minutes during the race. In 2019, Coury beat the horses by more than 75 minutes and was the legitimate overall winner. In 2021, he beat the horses by 73 minutes. Also, later that year, Coury, now a world-class ultrarunner, broke the American Record for running 24 hours, with a new mark of 173 miles.

Conclusion

With all this information, has the debate been settled? Probably not. In 2009 the New York Times published an article that observed: “But when it comes to long distances, humans can outrun almost any animal. Because we cool by sweating rather than panting, we can stay cool at speeds and distances that would overheat other animals. On a hot day, a human could even outrun a horse in a 26.2-mile marathon.”

Sources

- John D. Barton, A History of Duchesne County.

- Edward S. Sears, Running Through the Ages

- Andy Milroy, North American Ultrarunning: A History

- Geoff Williams, C. C. Pyle’s Amazing Foot Race: The True Story of the 1928 Coast-to-Coast Run Across America

- The Ipswich Journal (England), Nov 7, 1818

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Feb 21, 1840

- The Ormskirk Advertiser (Lancashire, England), Oct 4, 1855

- The Wells Journal (Somerset, England), Oct 13, 1855

- The States and Union (Ashland, Ohio), Oct 7, 1857

- Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (Pennsylvania), May 12, 1869

- Bucyrus Journal (Ohio), Nov 8, 1878

- Burlington Weekly Hawk-Eye, Sep 9, 1880

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Oct 16, 1879, Sept 15, 1880

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Feb 11, 1894

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Aug 10, 1908

- The Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct 3, 1957

- The Daily Tribune (Wisconsin), Nov 5, 1957

- The Uintah Basin Standard, Nov 7,21, 1957, Jul 24, 31, 1958

- The News-Review (Oregon), Nov 16, 1957

- The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), Nov 15, 17-18, 1957, Mar 4, 1958

- Bennington Banner (Vermont), Nov 18, 1957

- The Salt Lake Tribune, Jan 20, 1958, Apr 15, 1958, July 23, 1958

- Lehi Free Press, Jul 31, 1958.

- The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), Jul 23, 1958

- Great Falls Tribune, Jun 9, 1960

- The Daily Inter Lake (Kalispell, Montana), Jun 17, 1960

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Dec 23, 1936

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Dec 29, 1936

- The Amarillo Globe-Times, Jul 4, 1950

- The Salt Lake Tribune, Mar 28, 1943

- Casper Star-Tribune, Jul 24, 1958

- The Bee (Danville, Virginia) Sep 28, 1927

- Rocky Mount Telegram (Rocky Mount, North Carolina), Jul 23, 1958

- Tara Parker-Pope, “The Human Body is Built for Distance,” The New York Times, Oct 26, 2009

- Arizona Republic, April 6, 1984, April 29, 1985

- Albany Democrat-Herald (Oregon), Jul 25, 1849