Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:31 — 29.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

Both a podcast episode and a full article

After the golden age of Pedestrianism of the late 1800’s, a new breed of ultra-distance runners emerged in the early 1900s. Events were few. The world wars and the great depression all but snuffed out their efforts to continue to go the distance, to demonstrate what was possible. It became impossible to try to make a living with their legs. In America, only the most determined runner emerged out of the strife of the 1930s and 1940s to continue their craft into the post-war modern era of ultrarunning. One of these athletes was Alvin “Mote” Bergman.

After the golden age of Pedestrianism of the late 1800’s, a new breed of ultra-distance runners emerged in the early 1900s. Events were few. The world wars and the great depression all but snuffed out their efforts to continue to go the distance, to demonstrate what was possible. It became impossible to try to make a living with their legs. In America, only the most determined runner emerged out of the strife of the 1930s and 1940s to continue their craft into the post-war modern era of ultrarunning. One of these athletes was Alvin “Mote” Bergman.

In 1896 the first marathon was competed in the inaugural Olympic Games at Athens, Greece. The idea was quickly adopted elsewhere and the Boston Marathon soon was established. Other marathons followed and competing at that distance grew in attention. But there were only a small number of runners competing at longer distances such as 50 miles and 100 miles. The Trans-America races “Bunion Derbies” of 1928-29 did gather together talented runners, but soon America turned their attention to just surviving during the depression.

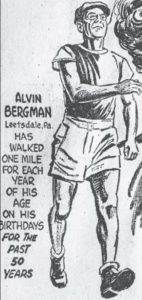

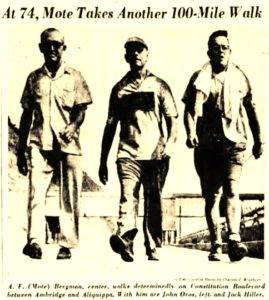

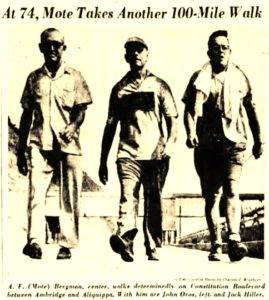

Without very many ultra-distance professional events to compete in, some of these early ultrarunners used their marketing creativity to transition to “solo artists.” Mote Bergman would eventually take this road in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area and would become known as “the wizard of the colossal art of walking,” and the “world champion birthday walker,” He was one of the very few American ultrarunners who kept up ultrarunning through the Great Depression, through the World War II years, and went on to span into the modern era. He was likely the first American to walk or run a sub-24-hour 100-miler in the post-war modern era of ultrarunning.

Early Running/Walking Career

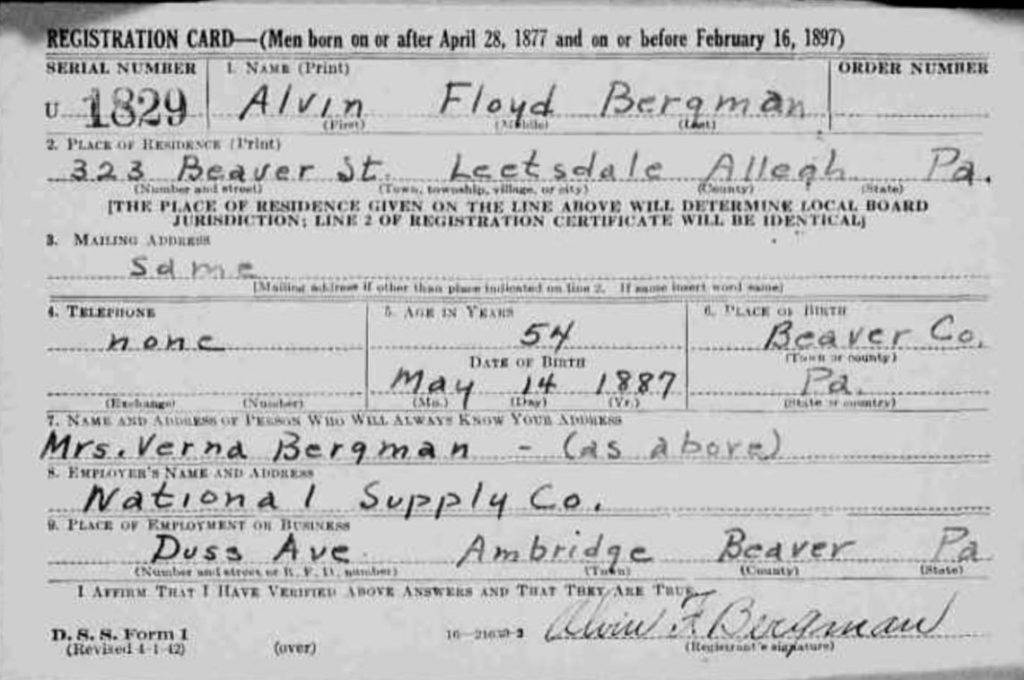

Alvin Floyd Bergman (Bergmann) was born in Virginia on May 14, 1887 weighing only four pounds. His father was a carpenter and his grandparents came from Germany. He was frail as a child and started walking for exercise when he was ten years old. His family moved to Leetsdale, Pennsylvania, a small town on the Ohio River outside of Pittsburgh. In 1900, at the age of 13, he began long distance walks to build himself up physically. He had read a story about the walking champion, Edward Payson Weston, who advised people seeking good health to “walk, walk, walk.” That year he started a very long string of his birthday walks, matching miles to his age. Those birthday walks were eventually featured in Ripley’s “Believe it or Not” column and Mote would keep them going until he was 80 years old.

He wasn’t a powerful looking man, only 145 pounds and 5 ½ feet tall. His nickname “Mote” was derived from his small stature. Mote became a barber, also turned into a professional runner in 1909, and participated in some running races. That year he ran a “marathon” of about 36 miles, near Pittsburgh, in a bad snowstorm and finished in 5:25. Late that year he also participated in a 72-hour “go as you please” race.

In 1915 at the age of 28, he achieved his most proud accomplishment. He walked from Pittsburgh to Chicago, a distance of about 503 miles in an incredible six days, 23:45, believed to be a “world record” at that time. During that trip he walked with pedestrian legends, Dan O’Leary of Chicago and Edward Payson Weston of New York.

Mote ran several years in a professional “foot running race” called “Pittsburgh Leader Race” that went from New Castle to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The race was billed as a 50-miler, but the distance varied each year depending on the route. It was probably closer to 60 miles. The runners were aided by helpers in horse-drawn buggies along the way. In 1915 the winner finished in 8:39. A 72-year old civil war veteran, and famous pedestrian, Stephen G.“Old Soldier” Barnes came in 17th. Wagering took place as to whether the old man would finish. Mote finished two minutes after “Old Soldier” in 18th. A few months later Mote and Old Soldier dueled against each other in a double Pittsburgh Leader, a two-day-stage race from Pittsburgh to New Castle and back for more than 100 miles. (Sadly later in 1919 “Old Soldier” Barnes came down with cancer, walked his last match and passed away that year.)

The 1916 Pittsburgh Leader Race was Mote’s finest year in that event when he finished in second place in a revised course that was closer to 50 miles. He would look back on that finish as his greatest race. He ran that race every year that it was held and was sponsored several times by a newspaper.

In 1929, at the age of 42, Mote ran 400 miles from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Dover, Delaware in seven days. He had prepared specifically for this event, piling up 1,200 miles in training. He hoped to compete in a race across America in 1930, but that event was never held. He did run 74 miles in 12 hours, in Philadelphia. In 1930 Mote tried to break a record running from his home 37 miles to New Castle, Pennsylvania, where a family reunion was to be held. Unfortunately he was stopped by a policeman and questioned for 50 minutes before he could continue on. He still covered the distance in 5:20.

Walking through the Great Depression

Mote’s real passion was for walking. He wasn’t out to set records. He just wanted to walk.’By 1930 he “slowed down” and concentrated mostly on walking. As he perfected his walking, he was able to maintain a speed of up to five miles per hour.

His local fame increased. He was mentioned in Ripley’s “Believe it or Not” publication. In 1936 he accomplished a 55-mile walk to Sharon, Pennsylvania, fueled only by a saucer of grapefruit at the start. When he arrived, he was greeted by the mayor and a band. In 1937 at age 50, his birthday walks began to get attention nationally. He said “A man is as old as his legs.” That year he claimed to have walked 250,000 lifetime miles.

Walking 100 miles in a day became a goal. In 1939 at age 52, he took his walking talents to the Leetsdale High School track where he walked/ran 100 miles in 22:05 on the quarter mile track. He would accomplish several other sub-24-hours 100s in the future. It was reported, “He frequently walks 20 miles before breakfast just to get up an appetite, and he always fasts as part of his training before a long distance stroll.”

The next month, Mote received a lot of national attention by walking about 400 miles to the New York World’s Fair in six days, five hours. Once there, he was honored by participating in a radio program.

In 1940, now age 53, Mote walked 150 miles to participate in a festival in Elkins West Virginia. His days were carefully planned to walk about 50 miles per day from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. At the festival, he participated in a wood-chopping contest and demonstrated his barber skills by shaving a man with an axe. Many other times he would do unusual things at the conclusion of a walk. Once after a walk to Washington D.C. he washed his feet in the fountain on the Capitol lawn.

Walking During World War II

Mote gave up the barber profession because it was “too confining.” In 1943, during the war, Mote was an auxiliary military policeman at a war plant. Gas rationing was in effect and the local newspaper thought it would be funny to do a feature on Mote because gas rationing was not a problem for Mote. It was reported, “Never in his life did he own an automobile. His only possible concern could be over his supply of walking shoes. But Mr. Bergman possesses five pairs, which at 5,000 miles to the pair and 500 miles to the sole, should last him for the duration.” Whenever he would buy a new pair of shoes he would put them on and wade in a bathtub full of water for an hour. Then he would go walk 40-50 miles letting them dry on the way. He said, “The shoes squish around a little but walking around in them for the rest of the day takes care of the squish. They dry out and fit like gloves.” The most miles he achieved on a pair of shoes was 10,000 miles. He would put a bit of tape around the backs of his shoes “to keep the stones from jumping in,” an early version of gaiters.

Usually his son, John Bergman (1918-1979), would keep track of his laps and times, but he was away serving in the Medical Corps, in England, so Mote’s wife, Verna (1889-1958), kept track of his long walk from the sidelines. She said that since the war started, Mote had worn out all his shoes and used all her war coupons. Every room in their house was littered with shoes. She said that after his birthday treks that he relaxed on their living room couch and required “bell service” from her to bring him cream for his feet or a little lemonade.” She joked that she covered nearly the same miles he does by fulfilling his requests.

Mote estimated that he had walked or run about 260,000 miles so far during his lifetime. To “keep in shape” he would fast three times a year from three to seven days. He said his secret was to just “put one foot in front of the other and push.” He described a long walk to be a distance greater than 25 miles. “I wouldn’t get dressed up for less than 25 miles.”

At the age of 58 in 1945, Mote, now a pipe inspector, set off to again walk about 500 miles from Pittsburgh to Chicago, duplicating his 1915 achievement when he covered the distance in less than seven days. He took off from the Post-Gazette building on a September afternoon in pelting rain. He had no intentions of trying to break his record. He just wanted to get there in time to watch the Chicago Cubs in the World Series. Mote sent money ahead to the hotels he would stop at. With the rain coming down, it forced him to walk on the cement pavement. He preferred to walk on the dirt shoulders. To fuel himself, he took along a mixture of dextrose and orange juice. But he said, “After 40 to 50 miles, I like a couple of bottles of beer. Then I’m good for another 10 miles.” His walk took 10 days and the weather was poor.

Mote had perfected the “ultra shuffle” and explained that the secret of long-distance walking was keeping the feet as close as possible to the ground. “I never raise my leg if I can help it and I never turn around and look back. That’s wasted effort and I find it means a lot.”

When Mote walked, he carried a two-foot long walking stick, not only to club dogs but to help with his balance. The stick was heavier on one end. When he first started out he would grip the stick on the heavy end but by the time he was nearing the end of his run, the stick had dropped and the heavy end was swung like a pendulum. He explained, “It give me momentum, sort of a push with each step.” On most of his walks that lasted a day, Mote didn’t eat along the way but would stop for orange juice.

Walking During the Post-war, Modern Age of Ultrarunning

In about 1948 he participated in a 75-mile race on a track, which was his last formal race. Mote explained, “There were 16 of us in it and all 16 finished. But at one point in the race they accused me of fouling – stepping on the other fellas’ heels and nudging them in the ribs. A fight broke out among the spectators when they accused me and while the fight was going on, somebody robbed the box office. I came in third and got 39 cents.”

Mote’s Atlantic City walk was successful. It only took him about eight days. As soon as he arrived he changed his clothes, ate, and took a walk on the boardwalk that he would grow to love. He planned to stay for a few days “to look over the bathing beauties.”

As with most of the running “solo artists” over the years, he was a blatant self-promoter who constantly sought sponsors to help fund his walks and he frequently found them. He would get sponsorships from the clubs he belonged to and local businesses. While he gained national fame, he was never rich and stayed true to his main message: “My advice to all if they want to enjoy good health and long life is to walk, walk, walk.” He told reporters continually that he had a transcontinental walk across America in his near-term plans, but he never attempted it, probably because of the lack of sponsorships.

Mote’s worst obstacle during his walks were usually dogs. He said, once while walking across Indiana a “dog tried to make a dinner out of me. My foot swelled up like a watermelon, but I recovered after treating myself with beer and whisky. Not the dog though. He died.” But Mote loved dogs and very often walked with his dogs. He had one dog that lasted 70,000 miles. “They’re the best companions on the road you can get. No matter what the weather is like, no matter how cold it is, they never complain about sore feet. I love all dogs, but all dogs don’t love me. Down through the years, I’ve had 13 dog bites.”

On August 26, 1950, Mote accomplished another sub-24-hour 100-mile walk. He walked through several towns with a car following to measure the distance on the speedometer. When it showed 50 miles, he turned around and started back. He finished in about 23:30. It was likely the first sub 24-hour 100-miler accomplished by an American in the post-war era of ultrarunning.

Mote continued his annual birthday walks and at age 65 walked from Detroit to Pontiac, Michigan and back, for the Detroit Elks Club. His wife, Verna, was asked about his walking hobby. She replied, “It’s a better hobby than hunting or fishing. The only trouble is, he’s always too tired to enjoy his own birthday parties.” Verna passed away in 1958.

Over 70 and Still Going

Around his hometown, everyone knew him. He waved to all he saw when he walked. He explained that it sometimes had its disadvantages: “Once I was standing on the corner and I decided to take a bus. I waved at the bus driver and he just smiled and waved back, and kept on going.”

In 1961, Mote was sounding a little cocky when he offered $50 to anyone who could stay with him on a 50-mile walk through neighboring towns. He said about walks in the past with people, “A few can keep up with me for a while, but sooner or later they fall off – from exhaustion, stomach cramps or sore feet.” At the end of this walk he planned to dance at a bar. Two men took him up on his offer. One man was Young Kemper (age 44) who had been training with Mote. The other was John Oros (age 27) who was a golf caddy. Oros boasted, “After lugging two golf bags over both shoulders for 100 holes a day, I could walk to the moon and back.” By mile 20 the trio had walked for four hours. All three ended of doing well. Mote finished the 50 miles in 12:38, Kemper in 12:40, and Oros in 12:43. The two split the $50.

While 81 years old in 1968, Mote walked 25 miles to the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball home opener. His string of birthday walks likely ended that year to cap off an amazing birthday walk string of nearly 70 years.

In 1978, Alvin F. “Mote” Bergman died at the age of 90 in the Elks National Home, Bedford Virginia, where he had been living for the previous two years. He finished his walking career with about 385,000 miles. Mote set his mark on ultrarunning history by being one of the very few Americans who spanned the pre-war era of ultrarunning into the modern era. While he didn’t participate in races after about 1948 because they were few and far between, he most likely was the first American to cover 100 miles in less than 24 hours during the modern era with his walks in 1950 and 1961.

Sources:

- Pittsburgh Press, Jan 31, 1909, May 10, 1914, Mar 24, 1915, Oct 7, 1931, Sep 30, 1940, May 12, 14, 1944, May 12, 1946, Aug 21, 1949, Apr 11, 1965, Aug 15, 1949, Jul 3, 1961, May 6, 1967

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Oct 26, 1917, May 24, 1943, Sept 24, 1945, 15 Aug 1949, Aug 28, 1950, Sep, 9, 1958, 21 May 1960, Jul 4, 1961, Sept 5, 1961, May 7, 1962

- Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Jul 25, 1936, Jun 6, 1939, Jul 20, 1941

- South Bend News-Times, Nov 7, 1914, Dec 11, 1914

- New Castle News, 27, Oct 1915, June 7, 1916, 19 Aug 1930

- The Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), Aug 22, 1930

- The Indiana Gazette, Sep 24, 1945.

- Pittsburgh Daily Post, Dec 4, 1916

- The Morning News (Wilmington, Deleware), Aug 7, 1929

- Nebraska State Journal, Oct 4, 1945