Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:32 — 27.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

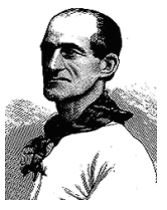

Peter Napoleon Campana (1836-1906), of Bridgeport, Connecticut, known as “Old Sport,” was recognized as the most popular and entertaining “clown” of ultrarunning. It was said of him, “Campana kicks up his heels and creates a laugh every few minutes.” He was one of the most prolific six-day runners during the pedestrian era of the sport. All of his amazing ultrarunning accomplishments were made after he was 42 years old, and into his 60s. He competed in at least 40 six-day races and many other ultra-distance races, compiling more than 15,000 miles during races on small indoor, smokey tracks. He never won a six-day race, but because he was so popular, race directors would pay him just to last six days in their races. Admiring spectators would throw dollar bills down to him on the tracks during races.

Peter Napoleon Campana (1836-1906), of Bridgeport, Connecticut, known as “Old Sport,” was recognized as the most popular and entertaining “clown” of ultrarunning. It was said of him, “Campana kicks up his heels and creates a laugh every few minutes.” He was one of the most prolific six-day runners during the pedestrian era of the sport. All of his amazing ultrarunning accomplishments were made after he was 42 years old, and into his 60s. He competed in at least 40 six-day races and many other ultra-distance races, compiling more than 15,000 miles during races on small indoor, smokey tracks. He never won a six-day race, but because he was so popular, race directors would pay him just to last six days in their races. Admiring spectators would throw dollar bills down to him on the tracks during races.

He didn’t age well, lost his hair, had wrinkled skin from being outdoor so much, and people thought he was 10-15 years older than he really was. He never corrected them in their false assumption and wanted people to believe he was very old. While he was well-loved by the public, he wasn’t a nice person. During races, when he would become annoyed, he would frequently punch competitors or spectators in the face. In his private life, he was arrested for assault and battery multiple times, including abusing his wife, and spent time in jails for being drunk.

Read about the fascinating history of the more than 500 six-day races held from 1875 to 1909 in Davy Crockett’s new definitive history in 1,200 pages. Get them on Amazon.

Campana’s Youth

As a young man of about twenty years old, in 1856, Campana moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut. He became a peddler of nuts and fruit, and at other times operated a corner peanut stand. “He soon became known in Bridgeport as an expert and fearless volunteer fireman and did good service at several large fires. He was always a fast runner and was noted for his courage and promptness of action in time of danger.” He made a challenge to all New England runners in a five-mile race to win a belt. He won the race that took place in Providence, Rhode Island.

Life Before an Ultrarunner

In 1860, he lived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, again working as a fireman. He once challenged the entire fire department of the city to a half-mile race. The challenge was accepted, and he won in 2:30. He competed in several races up to ten miles and won many. He beat a noted runner, “Indian Smith” at ten miles, in 57:26. That year, he married Mary (1840-) and had a son Napoleon Campana (1861-1862) who died as a young child. They later had another child that died young.

In 1875, he stopped a runaway horse team in the city, saving several lives. He was injured in the act and rewarded with a gold medal and a new peddler’s wagon. The city wanted to hear his story and put on a ball for him, displaying his new peddler’s wagon in the ballroom. At the largest ball known in the city, he was able to line his pockets with plenty of congratulatory money. But it was said, “He is free with his money when he has any.” He became popular with the young boys of the city.

By early 1878, he didn’t have a great reputation around town and was referred to as a “loafer.” “He has been knocking around the street in a vagrant fashion for a year or more, doing nothing, and as he expresses it, ‘sleeping on a clothesline, and only getting a square meal once a month.” He became inspired by two men who walked 100 miles in Bridgeport. He started to train himself and was able to walk to Danbury, Connecticut, and back, about 48 miles, in 12 hours. “On another occasion he went out to Waterbury, 40 miles, and walked in, beating the milk train that distance, which showed either that he was a very fast walker, or that the milk train was short-winded.”

Seeking the Six-Day World Record

The Start

Campana started impressively, reaching 50 miles in 6:55:00 and 100 miles in 17:35:53, claiming an American record, breaking Charles A. Harriman’s recent record of 18:48:40. He peronally helped keep track of his laps by putting a mark on the wall for each lap. It was a slow way to keep record of the progress. “He weighs about 145 pounds, is of rather slight build, and as wiry and gritty as an Indian. He has a slight swelling at one knee and at the ankles, but it does not perceptibly affect his gait. He underwent no preliminary training. No one supposed that he would last the day out. To say that Bridgeport is astonished over what he has done, would be putting it mildly. He sometimes wore street shoes and sometimes slippers. He walked and ran in a pair of shoes that did not fit him. He lived on potatoes, beef tea, toast soaked in beef tea, bread, a little beef, milk, and tea.” For much of his walk, he did not have proper food. He kept three dogs in the hall and one of them frequently walked with him. “A short time ago, before the walk began, one of the best-known citizens of Bridgeport kicked one of his dogs and Campana blacked the man’s eye.”

“There was a certain business air about the way that Sport and his dogs set about the task. The old hall wore a very dejected look on the night of the start, with the exception of the presence of about 300 of the gang. The president of the Athletic Club was referee and starter. Dancing parties had been prosperous all through the winter, but after Sport had been walking two days, five couples could not be found at the dance halls, and, in fact, the prayer meetings could not get a quorum. The neighbors who would, under ordinary circumstances, scorn to be seen reading sporting news, could be found reading accounts published in the local papers of the wonderful feat Sport had so far accomplished. The men and even the female portion of the community got very excited, and were it not for the dense clouds of tobacco smoke thick enough to be cut wiith a knife, that came out of the hall windows, the fair sex would certainly have applied for admittance too see the wonderful performance.”

“The fourth day was a terrible one for Sport who had reduced himself almost to a skeleton by his long and persistent fight to swamp the previous performance of O’Leary. The dogs, who appeared so happy at the start, annd who had set the pace for their master, also wore a very serious expression, and to gaze on them with their skinny frames and sad faces, it could not fail to recall the song of ‘Old Dog Tray.'”

Solid Progress

At one point, he refused to walk another step unless a mirror was hung up so he could see himself. His aid station was a side room with a bed of a straw mattress, covered with a sheet and blankets, bottles, lemons, old shoes with patches, and little white dogs scattered around.

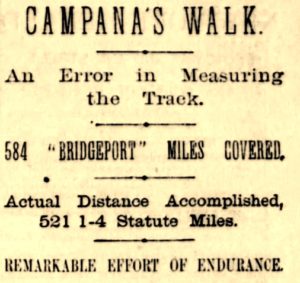

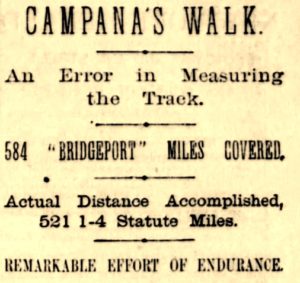

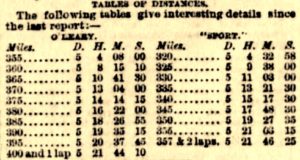

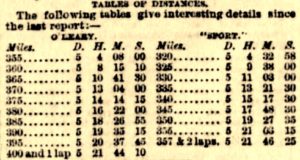

Bridgeport Miles

The attempt got the attention of some of O’Leary’s friends, who came to watch and became skeptical. A deacon of a local church came in and disputed the record. On the sixth day, the track was remeasured by the city surveyor, H. G. Schofield, and found to be 15.625 laps to the mile instead of 14 laps to the mile. He thought he was at 543 miles, but actually at about 484 miles. On hearing the news, Campana became discouraged and almost quit, but encouraged on by his handler, Samuel Merritt, who would become a very accomplished six-day runner. For the last day, Campana walked with one of his attendants. They wouldn’t let him know correctly how many miles he had left. They kept telling him that he had 42 miles left. “Early in the evening he was nearly discouraged and had thoughts of leaving the track,” but when they told him the correct number, he went off at a brisk run.

The Finish

“The news spread throughout Bridgeport and the surrounding country that ‘Sport” was likely to beat O’Leary’s distance, which caused Bridgeport to be in a state of excitement.” A “terrible” brass band came to play in front of the building. A crowd of 1,000 people surrounded the building, with another thousand packed into the hall. “With the howling, excited multitude, the scene resembled a perfect pandemonium.” Another 5,000 people crowded Main Street, waiting to hear the result. “As the end approached, the crush became absolutely dangerous, and the policemen had all they could do to preserve a narrow passageway for ‘Sport’ without resorting to violence.”

Campana finished with what he thought was 521.25 miles, breaking O’Leary’s 520 miles record. “The crowd cheered him until the walls shook and a number of bouquets what had been sent to him by some ladies of Bridgeport were handed to him. ‘Sport’ was hoisted on the scorers’ table and called upon for a speech, in which he thanked the people for their kindly interest.” His friends then picked him up and carried him from his track to his hotel room. “Sport was the hero of the hour, and after he was attried in his very scant costume, he was carried to the best hotel in the town, where one week before if he had applied for admission, they would have set the dogs on him.”

Tragically, Campana’s favorite dog died of exhaustion soon after the race. “The faithful canine was planted about two miles outside of the town, where a wooden slab marked the spot where Sport’s pacemaker came to an untimely death.”

The performance was deemed “not sufficiently authenticated to entitle him to a record. Next time he must walk his next race neither in Bridgeport miles nor by Bridgeport count.” People started calling him “Old Sport” instead of “Young Sport” because he looked old with his weathered face and receding hairline.

Campana was confident that he had broken the record and was willing to prove his abilities against the best. He became an instant celebrity in Bridgeport, quickly divorced his wife, and married a new much-younger woman, Jennie A. (Dalton) Campana (1840-), also known as Mary Jane Dalton. They already had a daughter, Mamie Campana, who was born in 1877. Jennie had been a member of Kiralfy’s orginal “Black Crook Company” that put on musicals. She had also been in other leading burlesque companies.

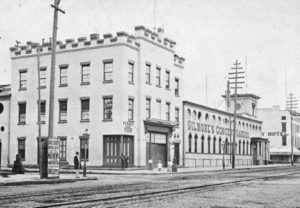

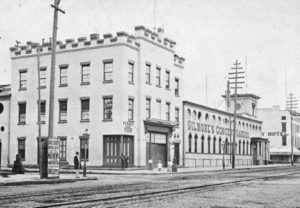

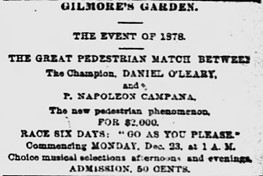

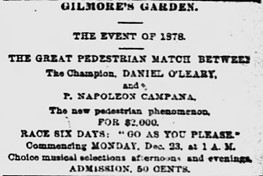

Six-Day Race against Daniel O’Leary

The head-to-head race was scheduled to be held in the greatest arena of the era, Gilmore’s Garden in New York City (later renamed to Madison Square Garden). Campana arrived in New York City the day before the race with his new wife, Jennie, and Fred Englehart, who would be his handler. Making his way through a storm, he went to Gilmore’s Garden, where he met with O’Leary and his backer, Al Smith. Two separate rolled sawdust tracks were ready to be used, one for each competitor, nine laps to a mile and eight laps to a mile. While a temperance meeting was being held in the building, they flipped a coin, and O’Leary chose to walk on the inside track. The outside track was viewed as the best. O’Leary was being nice to Campana, who was a bundle of nerves, facing a world-class competitor for the first time. “It is impossible for him to keep still for five seconds, except when asleep.” Neither man seemed over-confident. The wager settled on, was for $1,000 as side.

The Start

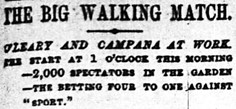

Both men occasionally broke out into a run. After ten hours, Campana had established an eight-mile advantage because O’Leary’s took an early two-hour break and suffered from a blister on his heel. “The blister increased in size, and continued to trouble him very much all day, besides causing him frequently to leave the track for a few minutes to change his shoes. He did not limp or show that he was suffering, but walked with a firm step, erect head, and perfect carriage of his body.” William Edgar Harding (1848-), editor of the National Police Gazette, was O’Leary’s handler, and he downplayed the effect of the blister to reporters. Campana battled an upset stomach and took frequent doses of Jamaican ginger and “laudanum” (tincture of opium).

The First Day

The Race Progress

During the second day, Campana left the track frequently, but only for a few minutes at a time, “but was to be seen at all times shambling around apparently ready to fall to pieces at each step.” He was nearly always accompanied by one of his attendants, who kept a step ahead of him trying to spur him on. His dogtrot degraded into a shuffle in which he hardly lifted his feet from the ground and plowed through the sawdust.”

In the evening on the second day, Campana’s appearance was rather disgusting. “His breeches slipped down so as to leave visible an expanse of dirty underclothing at the waist.” His legs were wrapped with bandages. He left the track reaching 150 miles, and looked as though he could not walk another step. O’Leary went into the lead at that point. “Careful treatment has caused the blister on his heel to disappear. His step is springy and elastic. He walks in perfect form, with head erect and arms swinging easily, and maintains without a break, hour after hour, a steady five-mile gait.” He finished the day with a six-mile lead and 156 miles. Knowledgeable sporting men understood that this was a poor distance for two days during a six-day race. O’Leary held the 48-hour world record of 207.5 miles, set in 1877. At midnight cries of “Merry Christmas” were shouted to O’Leary.

On Christmas Day, it became very clear that O’Leary would win. Halfway through the week, about 40,000 people had watched the race so far. A New York Times reporter couldn’t understand the fascination given by many toward the race. “Thousands who, despite the manifold discomforts to which they were subjected, found a mysterious fascination in the place that compelled them to linger hour after hour, gazing at the contestants and yelling themselves hoarse over the mediocre exhibition to which they were treated. The clouds of dust and tobacco smoke that were so dense that from one end of the building to the other was invisible, made an atmosphere that was terrible to breathe, and proved very distressing to the pedestrians.” The Christmas crowd was very lively and drank lots of beer and strong liquor. “Fights were of frequent occurrence, and many a tattered and bloody individuals were marched off by the police, of whom a large force was in attendance.”

Fred J. Englehardt (1839-) of New York City, the editor of Frank Leslie’s Sporting Times, and former editor of Turf, Field and Farm, was Campana’s trainer/handler. He had been involved in organizing and refereeing all sorts of sporting event including running, boxing, rowing, boating, and horse races. A couple of years earlier, he had handled Edward Payson Weston in an event and started to become more interested in longer-distance pedestrian races. He had observed Campana both during his Bridgeport solo six-day effort and this race, and said that Campana looked far worse than he did during day three at Bridgeport, but he was determined to run during the remainder of the race. The next day, Campana fired Englehardt “for alleged incompetency,” and replaced him with a well-known boxer, Barney Aaron (1836-1907).

Campana Crumbles

A reporter asked O’Leary if Campana was too old to on the track. O’Leary laughed and said he wasn’t too old, that others had done better. He then pulled a newspaper article out of his pocket from London Field, which he had been carrying around for a long time. It mentioned that Mr. Eustace, age 77, had walked 200 miles in four days, in 1792. Also, John Batby, age 55, had walked 700 miles in fourteen days, in 1788. O’Leary then said, “’Sport’ is lauded as being the best old man the world ever produced, and he is young compared to men who accomplished long distances nearly 100 years ago. As an extraordinary walker, I think he is a failure, but as a man of pluck, worthy of praise.”

Campana appeared on the streets that day after the race. “Those who recognized him were astounded at his exhibition of vigor and resolution after the dreadful ordeal through which he had gone.” After dinner, he went into a saloon and showed people his swollen, raw leg. Later, back at his hotel room at Putnam House, he was interviewed by reporters, with two dogs near him. The air was thick with the heavy odor of liniments. He gave some blame for his poor performance on shoes provided by O’Leary’s shoemaker that didn’t work at all. He implied it was a “put-up job” purposely designed to make him fail. He was also suspicious that the doctor may have wrapped his leg too tightly on purpose. The shoemaker denied the accusation and published a response stating that Campana had tested out the shoes well before the race and that feet were in perfect condition after the race.”

Campana’s Downfall

![]()

![]()

A second witness signed an affidavit that ten extra miles were given to Campana on the last day to help him reach 521.25 miles before time ran out. Campana never denied the charge, and started to call himself, “champion long-distance runner and walker of the world.” O’Leary would have never run against him if he had known that he was a fraud and pretender.

The press was not kind to Campana. “Campana proved an utter failure as a long-distance walker, and was of course, like all of his kind, ready with excuses for not having done what he promised. The truth is, that he is an old, played-out man, whose days for tremendous exertions have long since passed.”

Another article summed up the disappointing six-day race held at Gilmore’s Garden, “When someone has made a great hit in a particular line of public entertainment, crowds of frauds and pretenders are sure to foist themselves on the public, in the hope of raking in heaps of shekels. Pedestrianism is no exception to this rule. Frauds forced themselves before a long-suffering public.”

Campana received about $2,000 ($63,000 in today’s value) from the race against O’Leary. The original agreement was that he needed to reach 450 miles to receive any of the gate money. However, halfway through the race, when it became clear that he would not reach that amount, his backers threatened to pull him off the track, leaving O’Leary alone on the track, resulting in no interest in the event. O’Leary’s team agreed to guarantee Campana $2,000 if he stayed the entire six days.

Within a couple of weeks, he bought a new house in Waterbury, Connecticut, and furnished it luxuriously. After moving in, his new young wife Jennie pressed charges against Campana for beating and choking her, but they were reconciled. On his right leg, he had her name tattooed, “Jennie Dalton Campana” within a wreath. He was a man of many tattoos. On his chest he had tattoos of his sporting friends, including boxers John L. Sullivan and Yankee Sullivan. On his left hand he had tattooed, “Young Sport.”

Old Sport Campana would win back the spectators of the sport. He was just beginning… To be continued…

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part One

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Two

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Three

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Four

Sources:

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Nov 19, 1878

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 9, 29, 1878, Feb 13, 1888

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Dec 24, 1878

- The Cincinnati Daily Star (Ohio), Dec 26, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Nov 14, Dec 25, 27, 1878

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), Nov 14, 1878

- Buffalo Post (New York), Nov 16, 1878

- New York Daily Herald, (New York), Nov 16, 17, Dec 30, 1878

- The New York Times (New York), Nov 17, 19, Dec 15, 23-26, 1878

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Nov 19, 1878

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 7, 9, 1878

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Dec 23, 1878

- New-York Tribune (New York), Dec 24, 1878

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Dec 26, 1878