Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:06 — 30.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

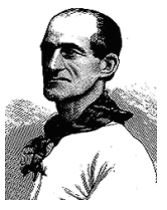

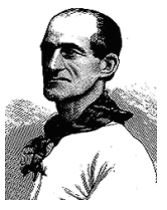

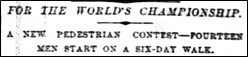

In early 1879, he had a poor reputation, and his integrity was questioned. But during the coming 15 months, as he ran more miles in races than anyone in the world, he would win over the hearts of the public. He would be called “perhaps one of the best-known athletes in the country.” He became a crowd favorite to watch in 1879 when the six-day race was the most popular spectator sporting event to watch in America.

| Learn about the rich and long history of ultrarunning. There are now twelve books available in the Ultrarunning History series on Amazon, compiling podcast content and much more. Learn More.

|

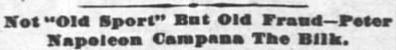

What was the reaction to the bombshell news in Campana’s hometown? “Bridgeport had freely given Campana their confidence and their backing. Now there is surprise that the community could have been sold so cheaply and completely. As a pedestrian, Campana is looked upon as a dead duck.” Still, there were those who believed his effort was legitimate. A reporter from another newspaper, who witnessed the last day of that event and interviewed witnesses stated, “I gained a firm impression that the walk had been honestly conducted, and that Campana had really passed over the number of miles with which he was credited. No one whom I met in Bridgeport appeared to have any doubt about the matter.” He believed there was a conspiracy against Campana. (Author’s note: Given that Campana never exceeded 521 miles in all his future 40+ six-day races that he competed in, I believe that the effort involved fraud and should be discounted. It is likely that Campana was naïve and wasn’t involved in the fraud that was conducted by his backers.)

Campana had a trial in late January for physically abusing his new young wife, Jennie A. (Dalton) Campana (1853-). She returned to her father’s home and took her new wardrobe and $100. “In court he showed a big roll of bills and said that he was in the hands of men who had hired him for a year, and he couldn’t walk anywhere without their permission.” He had argued with his wife when two other women came into their new house in Waterbury, Connecticut, who he didn’t want there. He suspected that she had him arrested so she could strip the house of costly things while he was in jail. Despite this terrible incident, the two were reconciled and Jennie moved back to their home.

On the Road

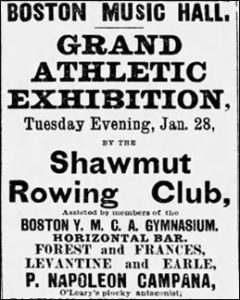

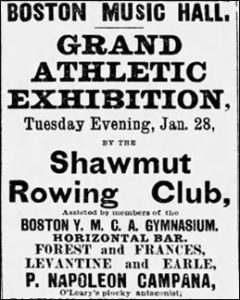

He went to Boston, Massachusetts, making an appearance at the Music Hall during a Shawmut Boat Club night of entertainment. He was still suffering from blisters that developed on his leg from the tight wrap during his race with O’Leary a month earlier. “Campana was on the program, and from his peculiar garb and long sloping walk, created much amusement as he sped round the track. When he entered the hall, a shout mingled with applause went up from the audience, which the pedestrian took very cooly as a broad smile overspread his peculiar face.” He ran on a temporary track, twenty laps to the mile, and reached five miles in 33 minutes.

He next went to New Haven, Connecticut, in March 1879 to attempt to run six-days solo. He reached 401 miles, a far cry from his previous alleged 521 miles. During the attempt, he rested for 33.5 hours. Later that month, he did not compete in historic Third Astley Belt Six-Day race held at Gilmore’s Garden, in New York City, but he was seen among the spectators “in his usual (fireman) red shirt.” He was referred to as “Connecticut’s big pedestrian fraud.”

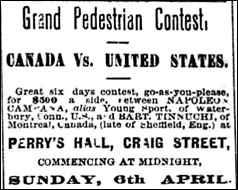

Six Day Match in Montreal, Canada

Campana stretched a lead of nine miles on the next day. “Both men were feeling fresh, but the feet of both are considerably blistered.” Campana held the lead after three days but “was badly used up.” On day four, he claimed that he had been badly treated. He had been promised a trainer and that his expenses would be paid in the amount of $95. But once it was determined that the race was not making money, he was denied any more help. He then accused Tinnuchi of running laps without the official scorer recording, which was true. Tinnuchi offered to credit Campana with 21 laps but was refused the offer. Then Campana said that he was told the race was being canceled because of lack of interest, when he had a 20-mile lead. He left the track with 248 miles, but his competitor went out again and was later said to be the winner with 400 miles, claiming the little gate money.

The referee countered this story and said that Campana threatened to quit the race until he was paid. He was promised to be paid after the race and asked to continue. Campana said, “No, not if my mother came out of her grave, except I get expenses paid beforehand.” The race managers believed that Campana was in such bad shape that he tried to find any excuse “to throw the match up.”

Campana left Montreal, went to Toronto to try to drum up a six-day race and complained “bitterly” of his treatment in Montreal. He still was a long way away from being the darling of the sport. A Toronto race did not come together.

Back to America

Campana fled back to the United States after his Canadian visit fiasco. He made an appearance on the last day of the American Championship Belt being held in Gilmore’s Garden in New York City, going down on the track to walk with his fellow Bridgeport runner, Samuel Merritt, who finished in second place with 475 miles.

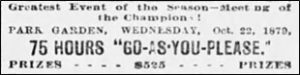

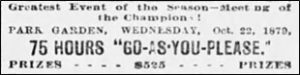

O’Leary’s 75-hour Race in Boston

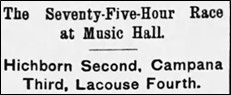

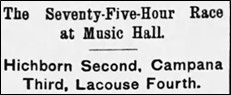

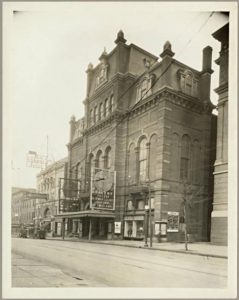

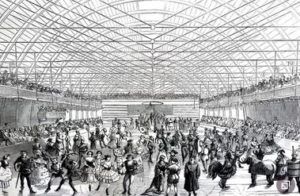

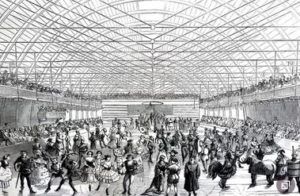

Daniel O’Leary started to hold a series of ultra-distance races. One format was a 75-hour race, different from a six-day race where they ran for 12.5 hours per day. The 75-hour race was a three-day race with three additional hours, so it could be run during four prime-time spectator evening hours. It started at 8 p.m. on Wednesday and concluded at midnight on Saturday. In July 1879, Campana competed in an O’Leary 75-hour race that was held in Boston’s music hall. The attraction was a to get a share of the winnings, a purse of $550 of gold. The race manager was Fred J. Englehardt (1839-1901), of New York City, editor of Frank Leslie’s Sporting Time, who had handled Campana during his race against O’Leary.

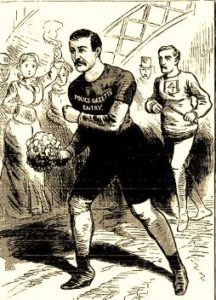

For the finish, the Boston Music Hall was packed like never before. During the final hours, when Campana returned to the track after a rest, he was accidentally knocked down by a spectator, hurting him somewhat. “He soon braced up and stared on a run, the audience cheering him lustily. Shortly afterwards he was the recipient of a very handsome bouquet from a lady, which he carried round the track in great triumph for two laps. Then placing the flowers on the scorers’ stand, he renewed his pedal work.” Later, he became “sullen” and wanted to quit. “He could hardly stand on his feet, and, with tears streaming down his thin face, showed a desire to draw back.” Cheers of “Go on Old Sport” made him run again “like a deer.” In the end, he finished in third place with 262 miles and won $100 (valued at $3,200 today).

A reporter who was emotionally affected by witnessing Campana’s finish went to visit him the next day at the hotel, Adams House, expecting to find him sick in bed. “Much to the surprise, he saw the old man standing in the center of a group of interested listeners, talking of the good old days, and the race.” Campana said O’Leary was the greatest pedestrian alive, and that he was the next best. They were invited to come visit his nice home in Waterbury, Connecticut and “the nicest dogs you ever laid eyes on.” He praised the race staff for taking care of him during the race. He railed against his former backers, Michael O’Rourke and John Scannell, who had taken advantage of him, charging him fees for things in past races.

O’Leary’s 75-hour race in Providence, Rhode Island

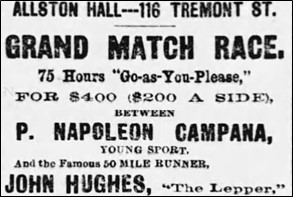

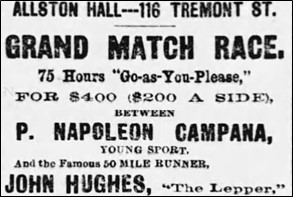

Campana vs. Hughes 75-hour Race

The race began on September 3, 1879. The track was tiny, 28 laps to the mile. Hughes at once sped into the lead and kept up a trot for 30 miles before walking. Campana yelled to the crowd, “I am all right, an old fire boy, no one can beat ‘Old Sport.’” He got an enormous cheer. At 48 hours, Campana had covered 183 miles, six miles behind Hughes. Campana wore a truss when he ran because of two bad hernias. Hughes won the race and $200 from Campana, covering 275 miles to Campana’s 271 miles. “Both men appeared used up.”

Two weeks later, Campana was seen on the streets of New York City making his way to Madison Square Garden to watch the Fifth Astley Belt six-day race that would be won by Charles Rowell (1852-1909) of England. Campana was recognized by those on the street, surrounded and cheered. He was now a pedestrian celebrity.

Six-Day Race in Baltimore, Maryland

Campana went to Baltimore to compete in a six-day 12.5-hours-per-day race in the Academy of Music held in late September 1879. Hughes again got the best of him, winning with 376 miles. Campana finished in fifth place with 329 miles. He went around the track several times holding high the American flag. A couple of days later, he was back at Madison Square Garden, watching the First O’Leary Belt. He still had not entered a big-time six-day race, but loved to make an appearance and get some attention from his fans.

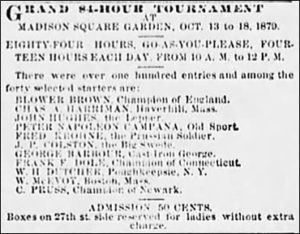

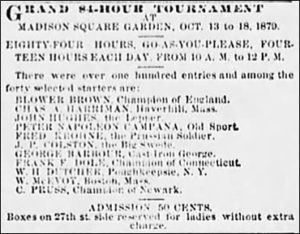

Grand 84-Hour Tournament in Madison Square Garden

After the first fourteen-hour day, Campana was in a respectable seventh place, with 71 miles, ten miles behind the leader. On the second day, he moved up to fourth place with 133 miles. The New York Sun was not his fan. “Campana’s tights were looser and more dingy and had more and more outrageous smears on them than those of any man on the track, and in the point of general disreputability of appearance, he was without a competitor.”

On the fourth evening, there was a lack of excitement in the building because of all the empty seats. “Campana was the only one of these who exhibited any exuberance. It was hard to see why he should feel the happiness that his face denoted. His left knee was done up in a handkerchief, and the varicose veins in his patriarchal ankles were swathed in bandages until his legs looked like piano legs done up to prevent scratching. His body bore every appearance of having been for several hours in a threshing machine, and yet his miraculous head rolled in a gleeful sort of way between his shoulder blades, which were elevated to make a socket for it, and the grinning ends of his crescent mouth touched his waving ears.” Despite his unfair critics, he was in second place, among the eight survivors, with 259 miles.

On the last evening, 3,000 spectators attended and Campana fell into third place. He generally had a problem performing well on the last day of six-day races. “The gas lights began to glow on Campana’s polished head. He evoked considerable admiration by sitting at the side of the track in a chair enveloped in a sheet and looked like an infirm and bald-headed Roman in a toga.” He finished in third place with 363 miles, earning $400, valued at $13,000 today.

Final Races for 1879

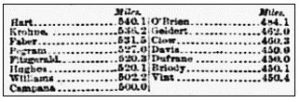

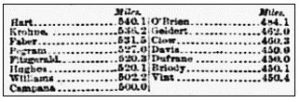

In November 1879, he competed at Newark Rink in Newark, New Jersey in a six-day, twelve-hours-per-day race. Frank Hart set the world record for this six-day format with 373 miles. Campana finished fifth, with an impressive 354 miles in front of 5,000 people.

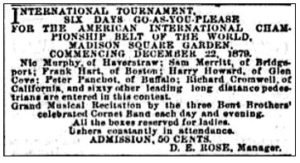

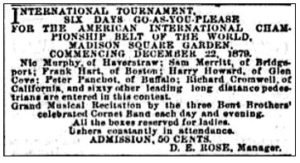

The Rose Belt in Madison Square Garden.

Campana fed on a diet of fish balls and hard-boiled eggs. He said to his handler, “Give me fish-balls, and I’ll fly.” The rougher portion of the spectators occasionally amused themselves by shouting sarcastic and insulting remarks at Campana. No one thought he would win. The bookmakers would not give any odds for him to win. But on the third day, he was still in the mix, in 11th place. “The old man was in fair trim, looking much brighter than on the previous day.”

As the race went on, Campana became the focus for the spectators. “Old Sport, attired in scarlet, attempted a brush with ‘The Lepper’ (John Hughes). The more Campana ran, the more he bent his head over his right shoulder. When about the pass Hughes, he began his wobbling motion from side to side in the middle of the track and plunged ahead at great speed. He caught up with Hughes once, but was unable to maintain the pace, and notwithstanding the cries of the spectators, he fell back again into his old limp.”

The newspapers were finally positive about Campana and his impressive performance. “Campana, who has been christened the ‘clown of the track,’ as usual created much merriment during the match by his peculiar antics. Considering his physical condition, his performance was considered a wonderful one.”

In Buffalo, New York, it was written, “’Old Sport’ was probably the worst used up man of the lot. After making the greatest effort of his life (500 miles), blistering his feet until they became perfectly raw, and otherwise badly injuring himself, his portion of the gate mounts to nothing.”

For the 1879, in Campana’s eleven ultra-distance races, he covered 3,527 miles.

1880

Head-to-Head 75-hour Match in Brookyln, New York

The Hall was filled for the start. Many were there simply to see Campana. The track was 24 laps to the mile. “Campana was in his usual walking rig, white shirt, blue cap with white stripes, black velvet trunks, red drawers and blue homespun stockings.” For the first few hours, he kept up a constant dog trot. “To a stranger entering the hall, it would appear from his looks and manner of running that he was just about to break down, but men who have seen him before know better, and have confidence in his powers of endurance. He was perspiring and panting, and occasionally slapping his thighs to prevent cramps. He has a most awkward gait when running. His head is leaned over the right shoulder, and his arms from the shoulders down to the elbows are jerked in a convulsive sort of way with each step he takes.” His wife, Jennie, stood at the door of his room and greeted him with smiles as he passed around the track, urging him to win. “She is quite a young woman in comparison to her husband, and of a pleasant demeanor.”

Lewis reached 100 miles first, in 25:20:00, with Campana five miles behind. To keep his lead, Lewis dogged Campana’s steps for hours. Campana claimed that Lewis, who was nearly six-feet tall, was crowding him and had stepped on his heels. He said, “I know Lewis is a faster walker than I am, but I think I can outstay him.” Campana would walk around the track carrying a little can with a spout containing beef tea.

Full-time Pedestrian

During the first half of 1880, Campana competed in about every race he could find, traveling to them with his wife Jennie. In February, he ran in a five-day fourteen-hours-per-day race on March 2, 1879, in Boston’s Music Hall. He finished in fifth place with 300 miles. At Boston, they joked, “It is denied that ‘Sport Campana’ was present at the time of the Israelitish exodus and led the tribes during their forty years’ wanderings. It is pretty clearly established that he was not alive at that time.” He next traveled north to Bangor, Maine and ran in a 27-hour race, reaching about 90 miles. Then just two weeks later, this amazing prolific runner ran in a six-day 12.5-hours-each-day race in Brockton, Massachusetts, in the Opera House, where he finished in fifth place, with 350 miles, again just out of the money. He finished two more races in April 1880, fourth place with 265 miles in a 75-hour race at Amsterdam, New York, against amateur competition, and at an O’Leary six-day twelve-hours-per day race in Buffalo, New York, in the Pearl Street Rink.

Six-Day Race in Buffalo, New York

At Buffalo, they treated him well. “Napoleon Campana, better known as ‘Sport,’ is perhaps one of the best-known athletes in the country. Although well advanced in years, he appears to be possessed of tireless energy. He looks like a physical wreck and every stranger expects to see him collapse momentarily. He doesn’t drop but grinds off mile after mile. He goes shambling along in stocking feet with no more style than a bag of bones, his arms working feebly, head on one side and tongue out. Suddenly, like some inspired fossilized trotter, he shakes himself and spurts away at a gait that even the most fleet footed cannot maintain, and this peculiar ped has lived more than a half century. (Not true, he was only 43 years old).”

During the race, it was observed, “He might truthfully be termed the Lone Fisherman of the party, as he seems to shake off all companionship with competitors, and his gait is such that no one could dog him. He is tenderly cared for by his wife, who is an exemplification of womanly devotion.” When he was in a good mood, when his competitors passed him, he would say “Go it, my boy!” When he wasn’t feeling good, he was “inclined to growl.”

An admirer presented Campana with a “handsome pair of moccasins.” He was “happy as a schoolboy.” He also received a bouquet made from cabbages and radishes, which he ate. On the final day he was presented with a loaf of French twist bread and ran around the track triumphantly as he began to chew on the bread.

Near the end of the race, O’Leary carried the medal for the winner around the track. “Once when it was very temptingly displayed before Campana, the old fellow snatched it and dashed through the crowd for the door. However, he soon returned and amidst deafening applause, he ran down the track, side by side with O’Leary.” He finished in fifth place, with 340 miles, winning $50, along with a generous sum from O’Leary. He said, “Buffalo has used me well and I’ll never forget it.”

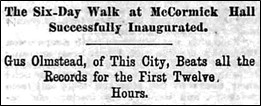

O’Leary Six-Day Heel-and-Toe Race in Chicago, Illinois

Campana competed well, and as always, was the race clown. During the evening of day three, he trotted around in his stocking feet as happy as ever. “He delights in wild colors, and his stockings and trunks of bright red make him conspicuous. ‘Don’t throw any carpet tacks on the track,’ he constantly cautioned the new arrivals as he drew attention to the fact that he wore no shoes. He sometimes struck a questionable gait for a square heel and toe walk, and when his attention was called to it by the spectators, he would make a reply that set the crowd in a roar.”

At the end of day four, Campana had 228 miles and was walking in third place, six miles out of the lead. This statement from a Chicago newspaper described him well. “’Old Sport’ Campana continued to amuse the spectators, who also had a respect for his persistency. He has developed staying qualities superior to those of the younger men.” He changed things up, as he was seriously competing. “Campana dropped his monkey movements and taken up a long swinging stride that reduced the number of miles between him and the leader considerably.” He received many presents from the crowd, including a silk walking cap which he prized greatly.

More than 2,000 people packed the building to watch the finish. Campana tried hard to move into second place but could not get there. He closed out with 327 miles, for third place, winning $150. It was one of his finest races.

Campana continued on the O’Leary race tour and went to Pittsburgh a week later and competed in a six-day 12-hours-per-day go-as-you-please race with sixteen starters. He again did very well, finishing in fifth place with 336 miles. “How he does it nobody knows, but he always manages to turn up for a place when Saturday night comes.”

Campana Retired?

After seventeen months of racing every month, once or twice, for a total of 21 races and 6,523 miles, Campana finally took a break and returned to Connecticut. During that seventeen-month period in 1879-1880, he was the most prolific ultrarunner in the world. In August 1880, he was seen on the streets of Bridgeport, selling pencils. For the rest of 1880, he did not run in any races. Everyone wondered if he had retired from the sport.

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part One

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Two

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Three

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Four

Sources:

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jan 26, 28-29, Apr 7, Jul 27, 28, August 10, 14-18, 27, Sep 3-5, Oct 26, Dec 29, 1879, Mar 28, 1880

- The Boston Post (Massachusetts), Jul 21, 28, Aug 27, Sep 4, 1879, Apr 27, 1880

- The Boston Weekly Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 30, 1879

- Boston Evening Transcript (Massachusetts), Apr 12, 1880

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Jan 8, 1879

- The Evening Post (Cleveland, Ohio), Jan 11, 1879

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Connecticut), Jan 25, Aug 15, 1879

- New York Times (New York), Mar 9, May 5-11, Oct 14-18, Dec 22, 24, 1879

- The Sun (New York, New York), Apr 20, May 5, Oct 14-19, Dec 23, 25, 1879

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Oct 11, 14, Dec 28, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Times (New York), Mar 12, Apr 8, 1879

- The Brooklyn Eagle (New York), Jan 18, 22-25, 1880

- Connecticut Western News (Salisbury, Connecticut), Mar 12, 1879

- The Montreal Star (Canada), Mar 19, 20, 1879

- The Kingston Daily News (Canada), Apr 7, 1879

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Apr 7, 1879

- The Gazette (Montreal, Canada), Apr 7, 11-12, 14, 1879

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), Apr 10, 1879

- The Hamilton Spectator (Canada), Apr 18, 1879

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Jun 20, 1879

- Buffalo Post (New York), Sep 22, 30, Dec 30, 1879, May 3, 17, 1880

- Buffalo Courier Express (New York), Oct 20, 1879, Apr 26-May 3, 1880

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), May 2, 1880

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Oct 5, Dec 28, 1879

- Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Mar 29, Aug 19, 1880

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), May 11-12, 15, 1880

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), May 13-14, 1880

- Chicago Daily Telegraph (Illinois), May 13-14, 1880

- The Daily Graphic (New York, New York), Jan 27, 1881