Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:42 — 29.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

He seemed to never be formally training, but perhaps with all the miles he put in pushing his cart, he was able to regularly run more than 300 miles in a six-day race.

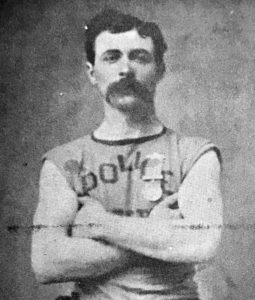

Campana was unusually “unbalanced.” When some spectators mocked him, he would punch them in the face and then continue running. The crowds would roar with approval and the race management would do nothing. The New York Times wrote, “Napoleon Campana, better known to the world as ‘Old Sport,’ is called the clown of the walking matches, and a race without ‘Old Sport’ in it would be a novelty.”

His eccentric nature was also seen in his personal life as a peddler in Bridgeport. His hot-headed nature would frequently end him up in jail. By 1880, his wife Jennie (Dalton) Campana had apparently left him again. He still loved her deeply and had her name tattooed on his leg. Even with the money he received at races, and with his national popularity, he appeared to be nearly destitute because he spent his earnings so quickly, likely on a lot of alcohol.

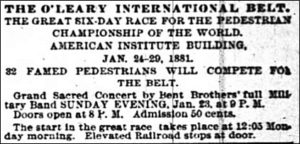

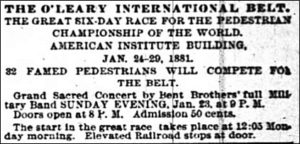

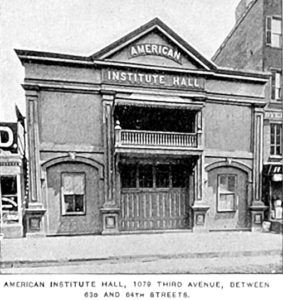

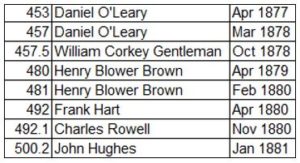

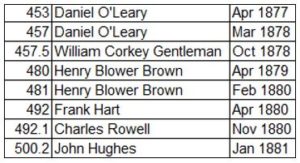

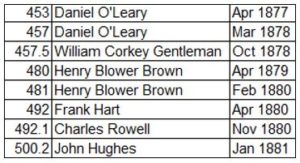

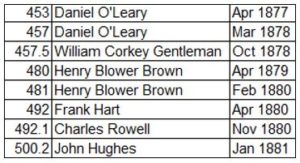

O’Leary International Belt

The Start

When Campana came out to the start line on January 24, 1881, he received huge cheers as spectators recognized him. At 12:05 a.m., thirty-one starters, arranged in ten rows, were sent on their way with the word “Go” by Referee William Buckingham Curtis (1837-1900), of Wilkes’ Spirit of Times. “With a bound, the men darted around the track, the new men mostly at the top of their speed, the more experienced and knowing ones at a steady jog.” Early on, Campana kept up with the frontrunners. After twelve hours, he reached 56 miles, eight miles behind the leader.

Crowd Favorite

On day three, Campana continued to be the main attraction on the track for the spectators. “Poor Campana appeared to be about used up. He made sidelong lunges in his endeavors to keep on his feet after propelling them over 230 odd miles, looking wistfully at the long lines of spectators for expressions of sympathy. The veteran then left the track for a few minutes. When he reappeared, an astonishing change had taken place in his apparel. His limp undershirt and trunks were covered with a Prince Albert coat, and a fine silk hat came down almost to his ears. He had washed his face and brightened up. After a while, he threw aside these habiliments and settled down to business in undress uniform.” Later, he was seen to be wearing a white slouch hat and held a large floral horseshoe “with barely strength enough to carry it around the track.” He strolled from one side of the track to the other, amusing the onlookers with his assortment of odd facial expressions, and seemed to change his costumes every 15 minutes. “He pays more attention to amusing the public by his antics than rolling up the miles.” He had received more bouquets than any other man on the track.

On the fourth day, “Campana ambled from one side of the track to the other, wearing an old white slouch hat, and making all sorts of odd faces to the amusement of the spectators. He reeled around the track apparently with no other purpose than to amuse the spectators. He changed his costumes nearly every 15 minutes, at one time appearing in a dirty suit of merino undershirt and red tights ‘a world too wide.’ At another time in a gorgeous crimson suit and a black silk hat, but always with a soiled bandana handkerchief tied loosely around his long, scraggy neck.”

On the fifth day, the race manager and pioneer six-day walker, “Daniel O’Leary, went on the track and ran once around with Campana, much to the delight of the spectators, who cheered, clapped their hands, and went into ecstasies.”

Antics on the Final Day

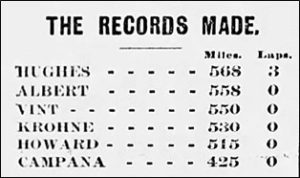

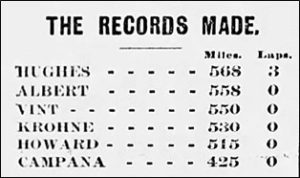

Hughes reached 500 miles in 118:48:00, crushing the world record by 14 hours and became the first person in history to reach 500 miles in five days, causing a tremendous uproar in the building. Only seven runners were still in the race, with Campana bringing up the rear, with 385 miles.

On the final day, Campana left the building unexpectedly to go drinking with some friends. The scorers assumed that he had quit the race. When he came back, he had to beg race officials to allow him back into the race, which they decided to do. Campana went back into his hut but was brought out again by applause. “He wore a disreputable felt hat, and seemed as happy as though the race had been laid on the plan of a donkey race, in which the hindermost beast wins. He ambled, provoking sympathetic smiles.”

Hughes broke Rowell’s six-day world record of 566 at about 6 p.m. “He ran around the track wearing an American flag. Campana trotted behind, holding a broom over Hughes’ shoulders. Campana wasn’t finished with his antics. When O’Leary brought out the O’Leary International Belt and put it on the scorers’ stand, Campana ran by and snatched it. O’Leary gave chase, and it took two laps before the trophy was recovered.”

Third O’Leary Belt

The New York Times wrote, “Campana is the same ridiculous clown that he was in the match in January. He has been paid to do the ‘funny business’ of this remarkable show.” The New York Tribune added, “His bald head glistened in the bright light like a billiard ball. Whenever anyone looked at him, he would dart forward with renewed vigor, his arms and legs flying in all directions as if hung on wires.”

![]()

![]()

Visiting Races

For the next couple of months, Campana visited high-profile races in the New York City area but did not compete. At a “Four-Cornered” six-day race involving four of the greatest runners and walkers in the world, held at Madison Square Garden, he came out on the track, uninvited and was very drunk. He was “unceremoniously hustled out.”

At another Madison Square Garden race, Campana was apparently selling things at the event. During this race Ephraim Clow (1854-1927) from Canada had been bribed to quit the race. When confronted by race management, he demanded $500 from them to continue. They refused and Clow stormed out to the building. Campana was sitting at the Garden door when Clow was leaving. “Campana, in language more forcible than polite, upbraided Clow for leaving the track, and asked for the price of the dozen bottles of imported ginger ale, which Clow had purchased from him. Clow told him to collect the debt in Hades and Campana walked away in disgust.”

O’Leary Heel and Toe Championship

Charles A. Harriman (1853-1919), of Haverhill, Massachusetts, took command of the race and reached 100 miles in 20:17:00. He set a 24-hour American walking record of 118.2 miles. Campana reached 93 miles.

On the fourth day, “Old Sport Campana still hobbles around the track, looking every moment as if going to quit, but he expresses a firm determination to stay with the boys to the end. The soles of his feet were said to resemble porous plasters, as he tolerates no interference on the part of trainers and has a reckless disregard for blisters.”

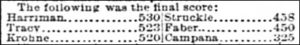

In the end, Harriman finished with a six-day world walking record of 530 miles, beating O’Leary’s existing six-day walking world record of 519 miles set in April 1877, in London, England. Harriman’s six-day record is still an American record today.

In Trouble Again

In August 1881, Campana went to Hartford, Connecticut, to run in a race at the Charter Oak Park picnic, but the weather washed the race out. “Finding nothing to do, he gravitated to the bars until his customary sure footedness was gone and found himself being towed to the lockup by a policeman. It took the station house some time to realize that the unfortunate with a sort of wet rag consistency was the hero of the pedestrian track. A friend gave him $1.40 to pay his fare home, and he was put on the ‘owl’ train early in the morning for Bridgeport. His only request of the police was to keep his name out of the papers as it would hurt his business.”

In October 1881, he was arrested again at Danbury, Connecticut and locked up for choking a small boy. In May 1882, another major six-day race was held in Madison Square Garden, the Diamond Belt. During this race, George Hazael of England became the first person to reach 600 miles. Campana came to watch. “Some amusement was caused by the ever-present Old Sport Campana, who wanted to fight the man who rolled him off the bench on which he was sleeping, and was noisy because he could no identify him. The dilapidated pedestrian had been in the building since the start and had slept as little as though in the contest.”

In June 1882, Campana turned into a hero again in New York City. He jumped into the water a rescued a young man from drowning after he tried to jump on board an excursion steamship after it had left the wharf. The youth fell into the water and sank three times before Campana jumped in and rescued him.

After being away from the sport for a year, Campana was still a celebrity. At Yonkers, New York, a famous tenor singer by the named of Campanini was introduced to an alderman in city hall. Not catching the name correctly, the aldermen showed excitement and said, “Campana, old boy, you do me proud. Why, see here you old rascal, I’ve got money up on you so just you waltz in and you’ll beat ‘em yet.”

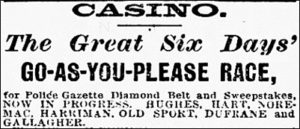

First Fox Diamond Belt

At the end of July 1882, Campana returned to competition. He ran in the First Fox Diamond Belt, held in Boston’s massive new Casino building. (A casino was a social club, not a place with slot machines). Richard K. Fox, of New York City, the publisher of the Police Gazette, to put together a six-day race. The track was the largest for the indoor six-day sport, five laps to a mile. The six-day race began at 12:05 a.m. on July 31, 1882, as Fox gave the customary word, “Go,” to the eight starters. The crowd of 5,000 looked small in the immense building. Campana fell behind a lap by the second mile. He reached 92 miles on the first day, 34 miles behind Frank Hart, the leader. “Old Sport (Campana) looked just as fresh as at the start. He, as usual, is the butt of the crowd.”

In the end, Hart reached 527.2 miles, and quit at about 9 p.m. The others followed suit and also stopped. “The crowd was large at the finish, and the enthusiasm intense.” Noremac reached 505.2 miles, Harriman 500.2 and Campana 360.2. Campana did not win anything, but a young lady admirer presented him with a gold ring. He became bitter that he was only given $5 and felt he had been treated poorly by the race.

A couple of weeks later, it was announced, “’Old Sport’ Campana is going to sue all the papers that have been saying uncomplimentary things about him.” A Boston newspaper wrote, “We have always considered Mr. Campana as the ideal pedestrian of the world, and vastly more competent than any man we ever saw, heard, or read of to cover the rear of a walking tournament.”

Campana Leaves the Sport Again

At the Championship of the World Six-Day race held in Madison Square Garden, in October 1882, spectators were on the lookout for Campana, who did not compete. “A lantern-jawed face, surmounting a warped and unhandsome figure was seen in the crowd, and somebody said: ‘There goes Old Sport Campana.’” When the mail service between New York City and Boston became disgraceful, it was joked that Campana be hired to make round trips, to solve the problem.

What was he doing? “Sport Campana, of Bridgeport, was turning an honest penny, peddling bananas and soda water.”

The Race of Champions

After being away from the sport for nearly three years, Campana, age 47, competed in The Race of Champions six-day race held in Madison Square Garden, in April 1884. The race featured Charles Rowell (1852-1909), of England, who came over, hoping to again make a huge fortune. Madison Square Garden was spruced up for what would be one of the greatest six-day races of the 19th century. “Inside the fresh sawdust track, clean floor, new fences and houses, and renovated seats gave the Garden a bright appearance.”

Out of money, the citizens of Bridgeport paid for Campana’s entry fee and expenses. He hoped to earn them a nice return on their money. He said, “I am going into this race like a gentleman. I shall put ‘Old Clinton No. 41’ over my door and that will be my battle cry for victory. I have made up a schedule of more than 90 miles a day. To do this, I shall eat food with plenty of blood in it. My daily rations will be six fish balls, eight quarts of milk, and thee quarts of beef tea.”

He was said to be “the old Italian fruit dealer of Bridgeport.” It was said, “His age is a delicate subject to discuss, but it is variously estimated from 35 to 50. He is about 5 feet 7 ½ inches in height and pulls the scale at 138 pounds.” He trained with others at Bernard Wood’s Athletic Grounds in Williamsburg (Brooklyn). That was the popular place to watch some entrants train, along with other professional athletes, including boxers. A bridge led curiosity seekers down to the ground-floor sawdust track that measured 16 laps to a mile. One morning, 1,000 men came to watch. “All that could be seen by most of the throng present was the bobbing heads of the runners as they ran around at the edge of the dense crowd on a seven-minute-mile gait.” Running for 20 miles (320 laps) was a typical session for the ultrarunners. Campana rested at Putnam House, across the street from Madison Square Garden.

![]()

![]()

After Campana had run only 47 miles in eleven hours, Samuel Day (1852-1913), originally from England, but living in America, who was leading the race with 74 miles, said something about Campana to another runner. “Campana, with a half shriek, half laugh, said, ‘Never you mind Englisher, you’ll have to swim home this time. You won’t make enough to pay your way back.’ There was a general laugh, and Campana showed his tusks and laughed until his head seemed about to part company with his body. He is by far the most awkward man in the building, and he knows it. He grins with delight when the people laugh at him and shakes his fist at them good naturedly. He plodded along as though he had got hold of some other fellow’s arms and legs by mistake, and his thin face looked drawn and worn.”

During the first evening, with only 71 miles, Campana said that he was done. He was suffering from colic. “They will have to draw me out with a rope if they get me on that track again.” He was annoyed that people yelled at him when he slowed to a walk. “They sing out ‘Run, you old fool, run.’ I suppose the people of Bridgeport will be mad at me, but I can’t help it. I don’t much mind being called Old Sport, but I don’t like the other name.” There was hope that with a few hours’ sleep that he would continue.

Campana and his trainer stayed in the building, trying to find funds to return home. “A drunken sailor wandered into the Garden during the early morning hours and two thieves got him into the bar room. They were appropriating his watch and money when Campana came to the rescue. The sailor generously handed him $3.” He now had money to return home.

Patrick Fitzgerald (1846-1900), of Long Island City, New York, went on to win the race and broke the six-day world record with 610 miles.

Back Home at Bridgeport

Campana went back to peddling things from his cart. One day, while watching some teenaged boys place baseball on a lot, he became offended by some of the remarks they made about him. He jumped from his cars and ran toward the boys, intent on clearing them off the field. “But the big lads were too much for him, and after they had rolled him around in the dirt and pounded him a little while, he escaped from their clutches, grasped each one by the hand, forgave them all around, and murmured, ‘Bless you, my children,’ and departed on a hop, skip and jump.”

For the November 1884 Connecticut senatorial election, five people wrote in Campana’s name on their ballots.

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part One

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Two

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Three

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Four

Sources:

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Jan 24, Aug 20, 1881, Nov 18, 1882, May 2, 1884

- The Sun (New York City, New York), Jan 24-27, 29-30, 1881, Apr 2, 23, 29, 1884

- The New York Times (New York), Jan 23, 24, 29-30, Mar 2, 6, 1881, Jul 31, 1882, Apr 27-30, May 2, 1884

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jan 7, 12, 23, 25-27, 29-30, Mar 11, May 10, 1881, Mar 2, Jun 1, Aug 2, 3, 6, 1882, Apr 2, 9, 28-29, 1884

- Boston Evening Transcript (Massachusetts), Aug 4, 29, 1882

- Fall River Daily Herald (Massachusetts), May 13, 1881, Sep 2, 1882

- New-York Tribune (New York), Jan 19, Feb 28, Mar 2, 1881

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Jan 24, 1881

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Jan 22, 1881

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Jun 4, 1882

- Brooklyn Eagle (New York), Jan 29, Mar 1, 6, 1881

- The Brooklyn Daily Times (New York), Apr 5, 1884

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Mar 6, 1881

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), May 13, 1881, Aug 1, 1882

- Connecticut Western News (Salisbury, Connecticut), Oct 19, 1881

- The Yonkers Gazette (New York), Jun 24, 1882

- The Hazleton Sentinel (Pennsylvania), Oct 26, 1882

- The Day (New London, Connecticut), Jan 24, 1883, Nov 20, 1884

- The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut), May 18, 1883, Apr 24, 1884

- Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Apr 2, 1884

- The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut), Jul 9, Sep 2, 1884