Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:34 — 24.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

|

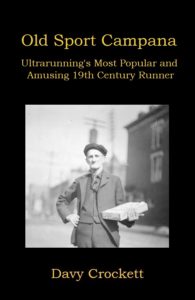

Another Retirement

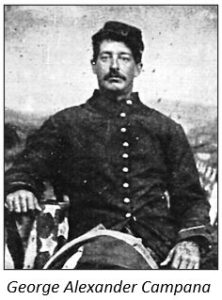

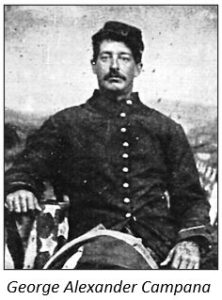

After May 1884, the number of six-day races declined. Those held until 1886 were more of a minor nature, and no races were held in Campana’s favorite venue, Madison Square Garden. It was written, “Walking matches no longer fire the public heart to the violence of a volcano”. The lull was mostly caused by a long financial recession until mid-1885, which contributed to tightening money. Campana did not compete in another six-day race for nearly three years.

He tried to enter the first major six-day roller skating race held in March 1885, in Madison Square Garden. “One of the familiar sights was the appearance of Old Sport Campana, the ancient rival of O’Leary, still wearing the peaked cap, red shirt and bandanna neckerchief, that made him the object of curiosity in days gone by.” He believed he could win the race, but the managers refused to let him enter, knowing about his clowning reputation.

Campana’s Fame

Campana was now recognized nearly everywhere he went. One day, he showed up in Boston. “A number of people followed the ‘old hero’ about town with no particular object in view, other than to see him. Finally, he went into one of the drug stores and purchased sixteen ounces of the tincture of Jamaica ginger, which he drank at once, on a bet. Everyone expected to see him drop dead, but ‘Sport’ is not one of the dying kind. It took considerable water and a good deal of profanity to cool his mouth off.”

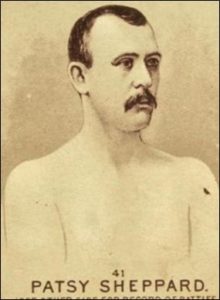

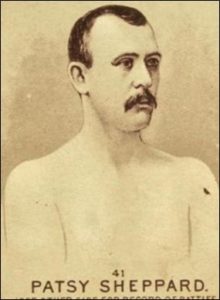

Later in the month, Campana was in New York City, examining a bunch of bananas in the warehouse of a Greenwich dealer. Going by, was a well-dressed man, with three friends who went into Smith & McNell’s hotel. Campana yelled out, “There goes John L. Sullivan and Patsy Sheppard (boxers).” That started a mob of nearly 500 men going to the windows of the hotel trying to get a glimpse of the famous athletes.

Campana Seriously Injured

At his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut, one day in June 1885, Campana was at a baseball game, cheering for Princeton instead of Bridgeport. He went too far, became abusive, and refused to leave. “The old man doesn’t like the Bridgeport team worth a cent, and he kept on with his voice regardless of consequences.

He ended up in the hospital for weeks, sick, in critical condition, and without money or friends. In August 1885, after six weeks, he was discharged, became a ward of the city, and was expected to die at any moment. A month later, he had recovered and seemed to be like his old self.

Campana the Peddler

Campana succeeded in peddling a new product. He said, “There’s no place like the New Milford fair. I went up there without a cent. I didn’t know what to do. Peanuts didn’t sell very well, and the outlook was bad. Finally, I went into the lemonade business. I found a friend to help me find some and I bought a barrel for ten cents and filled up with some stuff. The day was warm, and the countrymen were thirsty, and I sold the barrel of lemonade. Thirty dollars! A $30 clean profit out of nothing. I’m off for the Norwalk Fair too, and don’t you forget it.”

In October 1885, Campana went back into the peanut stand business in Bridgeport. He ordered 25 bushels of peanuts that came on a ship. But when a steamboat captain refused to deliver them to him and returned to New York City with the peanuts, Campana went to the city with the intent to “lick” the captain. “Old sport spent the greater part of the morning looking for the captain in the saloons. His energetic search made him very tired. Some of his old-time friends to whom he told his troubles were so anxious to see him lick the steamboat Captain, that they agreed to pay for his peanuts if he would do it.” Then somebody pointed out one of the crew of the steamboat. Campana attacked the man who wasn’t the captain. “The two were soon making the dust fly out of the floor of the pier. The old pedestrian was not hurt by the steamboat man, but he was made very uncomfortable by a shower of fish, lobsters, and several bags of his own peanuts as he left the pier.” He then went to find a lawyer to sue the steamboat company.

In October 1885, he was seen selling peanuts at the Danbury, Connecticut Fair. “His shouting attracts nearly all who pass by. He made so much money off his peanuts that he hired an assistant and supervised his peanut emporium in haughty leisure.”

In March 1886, he was seen in New Haven, Connecticut, peddling oranges. He went there hoping to arrange a running match against a local pedestrian, Uncle Willis Bunnell (1832-1903), but that did not come together. In June, he made news by simply visiting the circus at Hartford, Connecticut. Reporters were impressed by his crazy, colorful red shirt with blue stripes. They also were amazed that he had an encyclopedic memory of sports and records during the past 50 years.

In November 1886, Campana completed a tour with Barnum‘s circus (probably selling lemonade). There were rumors that he would run the first six-day race held in Boston in seven years, but he did not appear. Evidently, he was doing well with his peddling business. Runners who were in last place in races were said to be running “in Campana’s place.” Runners who displayed comedy while they ran were said to be “the successor to Old Sport Campana.”

The New York Times helped their readers understand what happened to Campana. “That unique figure of the six-days’ walking matches of years ago, Napoleon Campana, or ‘Old Sport,’ as he was popularly called, is not dead, as was reported some time ago. In fact, he is very much alive, and having lost the money he made on the sawdust track, and with it, the wife that the money brought him, he is now eking out a living by vending fruits in the streets of various New England cities. His gaunt, striking figure and his weird street cries, serve to bring many quarters and dimes to the pockets of this strange character.”

The Sport Wants Old Sport Back

As six-day races were held again, the sport continually tried to draw Campana back in during 1887. Races would publicize that he would be among the starters, but he was not. Connecticut scheduled a 27-hour state championship and had a struggle to get good competition to come. The race was to be held as part of the state fair held in Meriden, Connecticut, in September 1887, where Campana was employed, probably as a peddler. They really wanted him in the race because they knew he would be “a drawing card.” The weather did not cooperate, and the race had to be canceled. It rained hard and soaked the track. “Men were at work dipping up the water which covered it in some places by means of sponges.”

The local professional pedestrians, Alfred Elson (1836-1900), of Meriden, and George Darrow (1820-1906), of New London, were the runners that had to be in the race to make it legitimate. Money had to be raised to get Campana to come. He boasted that if the race had been held as originally scheduled, that he would have walked the competition “off their feet.” The race was rescheduled, but Campana had taken a fall at the fair and became injured. The race was held without Campana. Elson won after reaching 50 miles in 8:55. Darrow dropped out of the race early with stomach issues. The race was called a “big fizzle.”

Hall’s Six-Day Race

In 1888, Campana, age 51, was finally ready to return to the six-day sport. His friends in New York City paid for his entrance fee to the next major race to be held in Madison Square Garden. He immediately started training again in Hubbell’s Hall in Bridgeport and charged five cents admission to watch. “Old Sport is getting up his muscle by rushing about the streets of Bridgeport trying to sell oranges from two baskets, one on each arm. The exercise develops his lung power the most.”

His local newspaper declared, “Old Sport has entered in more six-day races and made smaller records than any pedestrian in the world.” The New York City press wrote, “He’s an old white-headed man, but tough. So long as a ghost of a show for a place in the receipts lasts, Old Sport plods along in the face of all odds. He bobs up at every race.” Meeting with the press the day before the race, “his long chin chapped energetically up and down as he told of past exploits.” He showed up at the Garden with his wardrobe wrapped in a string and overstated his age by four years.

It would be the first time that a six-day race would be held in Madison Square Garden since 1884, when Patrick Fitzgerald (1846-1900) broke the world record with 610 miles.

The event was put together by Frank Hall, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, assisted by William M. O’Brien (1858-1891), of New York City, the editor of the Sporting Times. New York City seemed ready for the return of the six-day race. Front page newspaper coverage in the New York papers was long and detailed throughout the race. This would be one of the most historic six-day races during the pedestrian era for American ultrarunners.

Twenty-five minutes before the start, the building was “packed as full as a sausage case” with up to 15,000 people. Because the building looked full, co-manager O’Brien decided to close the doors, not admitting about 2,000 people waiting to get in. All the seats were taken, and “a surging mass of people passed over the bridge to the ground inside the oblong oval track and soon it was impossible to make progress through the crowd there. There were knife boards, baseball targets, cane racks, places to buy railroad sandwiches and sawdust pie, soda-water fountains, peanut and popcorn stands, candy stands, fruit stands and a bar where 100 bartenders dealt out beer.”

To the delight of the crowd, Campana was the first of the 47 starters to appear on the track for the race. “A blue and white bandana swathed the old head of the peanut vendor. A gorgeous pink shirt followed after his gray and rather maugy neck. Blue polka-dot trunks came next and dirty gray drawers and old shoes completed the outfit. Works of the tattoo artist were seen on his weazened arms.” He received a loud ovation and acknowledged the attention by kicking up his heels. He would have to run fast on the first day because of a new requirement to reach 100 miles during the first 24 hours or be tossed out of the race.

Each of the runners wore black bib cards on their chests. The race began on February 6, 1888. They were given the word “Go” from Referee Peter J. Donohue (1861-1894), the sporting editor of The World. The scorers had a difficult time for the first few hours managing correct laps for the huge field of runners. Campana complained that he had been cheated out of some laps. Because of the large field and narrow eight-foot track, the men “jostled and interfered” with each other, making early fast records out of the question.

As dawn arrived at 7 a.m., the electric-colored globes of lights were turned off. The atmosphere in the Garden was already suffocating from cigar smoke. Most of the enormous crowd had left during the night, with only a handful of lifeless people in the seats. “Old Sport Campana plodded about painfully with glassy eyes and piteous gazes at the bulletin board which recorded his laps.”

After twelve hours, Campana “excited some amusement and applause by walking around the track with a huge piece of lemon pie in his hand.” At 16 hours, he was at the back of the pack with 66 miles. At 5:02 p.m. (17 hours), Campana left the track with 70 miles for an extended period. It was said that he would come back, but he did not. At the end of day one, only 25 of the 47 starters reached 100 miles.

By rule, those that did not reach 100 miles left the competition, including Campana. A Connecticut newspaper was embarrassed. “Campana was among the first to get out. He should leave the business and seek to make a living by other pursuits. He amounts to nothing as a walker and would probably never be heard of among men who possess any ability as pedestrians if he had to work to earn the money to pay as an entrance fee.” The next morning, he sat in front of his hut and watched the race. In the end, James Albert (Cathcart) (1856-1912), of Atlantic City, New Jersey, broke the world record and reached 621.7 miles. That mark is still the American six-day record today.

Clearly, after being away from the sport for so long, Campana wasn’t in shape to last for six days anymore. Back in Connecticut he said, “it would be a cold day (in Hell) when he enters another walking match.” He vowed to put all his efforts into peddling oranges and other green groceries.

Races in Connecticut

But he did not actually give up. In March and April 1888, he competed in two small local races in Birmingham, Connecticut, and did better. He reached 112 miles in a 27-hour race. He entered a small race in Ansonia, Connecticut. They tried to offer him $150 to enter, but he refused the payment and said, “All I need is beef tea, milk, Jamaica ginger and I’ll have a good supply this time, you bet. I’ll knock ‘em all out and don’t yer forget it. Yer can tell by my nose that I’m a stayer.” The reporter commented, “The nose is certainly a remarkable organ, both in size and color.”

He won the race and then made a speech. “Ladies and gentlemen (wiping his shining cranium with a bandanna), I’m kind of tired and I ain’t in very good condition tonight. I’m a little stiff in the limbs. The next time (brushing away a tear of perspiration from his nose) hope to give you a better exhibition. Now boys, take your girls to Easter service tomorrow. Good night.”

A week later, he ran in a 48-hour race in Birmingham, Connecticut, finished in third place with 200 miles, and won $50. He stayed on the track for the entire 48 hours. During that race, someone tried to stop him by drugging his liquor. He boasted that in the next six-day race he would stay on the track for 75 hours without sleep. He said, “I can go six months without sleep. In the next race, I’ll show what I can do.”

Old Sport is a Hit in the Theater

The O’Brien Six-Day Race in Madison Square Garden

Campana, now in much better shape, was prepared to enter another world-class six-day race scheduled for Madison Square Garden in May 1888. William “Billy” M. O’Brien (1858-1891), the editor of the Sporting Times, and William “Frozen Bill” P. Corney, (1843-1922), of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, were the managers of the race. Corney was tasked to sort through more than 115 applications, culling them down to those who he thought were the forty best runners. Campana was selected. Like recent six-day races, anyone not reaching 100 miles on the first day would be dropped out of the race.

George Littlewood (1859-1912), England’s current six-day champion, and the world-record holder for the six-days, twelve-hours-per-day format (72 hours), came to America to compete. The six-day world record holder, James Albert (Cathcart) (1856-1912), with 621.7 miles, chose to not compete and would come to only watch if someone was going to break his record.

The Start

Forty-four runners toed the start line on May 7, 1888, after midnight. Campana, age 52, was the first to come out of his hut. “His bald head shone like a billiard ball as he kicked up his ancient heels and munched his toothless jaws in a grimly sportive way. He was clad in a red and white undershirt, which needed washing, blue velvet knee-breeches, black stockings and Oxford ties.” He was greeted with wild applause.

“Once again Madison Square Garden is the scene of a tramping match. Once again, a sawdust ellipse is bordered by thousands of people interested in seeing how much a human frame can endure when striving for livelihood.”

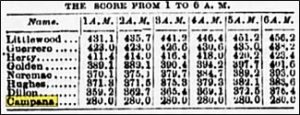

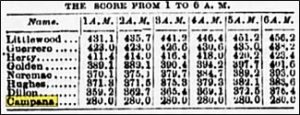

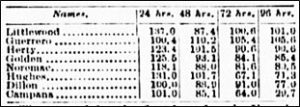

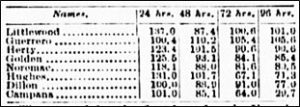

John “Jack” Edward Dempsey (1862-1895) the middle-weight champion boxer of the world, gave the word “Go” at 12:04 a.m. Littlewood and two others lapped the rest of the field at around the two-mile mark. Littlewood settled into the lead and reached 50 miles in 6:58. At 12 hours, Campana had covered 57 miles. Littlewood reached 100 miles in 15:39:00. Campana barely reached 100 miles within 24 hours, letting him continue in the race. “He worked his ancient limbs for 101 miles.”

Day Two

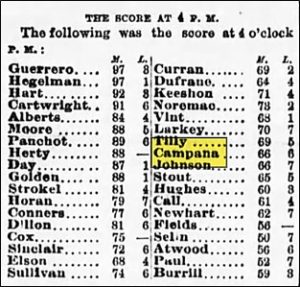

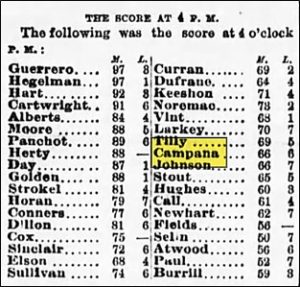

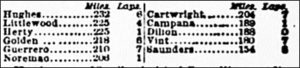

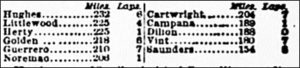

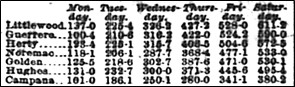

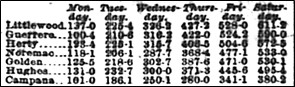

Campana was in thirteenth place after the first day among the 44 starters and continued to move up in the standings, as others quit the race. At 36 hours, he was in ninth place with 141 miles.

At the front of the race, there was hot competition for the lead between Littlewood and the “Lepper,” John Hughes (1850-1921), of New York City, the 100-mile American record holder. After two days, Hughes reached 232 miles, with a seven-mile lead over Littlewood.

Campana climbed into eighth place with 189 miles. The New-York Tribune called him “The wonder of the race,” and “The living skeleton,” and thought he was over sixty years old. Campana also added ten years to his actual age. He said, “I am 62 years old, and I haven’t got a tooth in my head and only a few hairs on it, but I’m here for sport, and don’t you forget it.”

With the smaller field and slower pace, Campana became one of the main focuses for spectators to watch. “Campana plays the clown as of old and eats strawberry shortcakes on the track when anybody is good enough to buy it for him.” The belief was that money handouts from spectators would ensure his participation until the race’s conclusion. “He created much amusement early in the morning. His knees were swathed in huge bandages. When opposite the scorers’ stand, he stopped, unrolled yards of rag and disclosed a big porous plaster. Tenderly lifting one end, he gently scratched his knee. This action, with the smile of satisfaction and relief which stole over his face, caught the crowd and they laughed uproariously. He grew very indignant at a lady who was slightly under the weather and who persisted in shouting at him, ‘Ah, there you Connecticut chestnut.’ He said he was just as young as the rest of them.”

![]()

![]()

Day Three

The New York Press observed, “Campana drank water now and then from a beer mug and seemed to enjoy it. His nose and chin seemed nearer together than ever, if possible.” The New York Journal wrote, “Poor Campana! His trousers are ripping. He toiled most wearily along, casting envious glances at his two attendants (Alfred Elson and John M. Sullivan), who sat in front of his hut and complacently smoked and watched the object of their motherly solicitude.” The New York World added, “Old Sport Campana was the merrymaker of the day. He looked very badly dilapidated at about noontime and dragged his legs after him heavily. He said, ‘I’m feelin’ a heap slight better’n I look.’ He is certainly a phenomenal old man. He has tired out a score of trainers who are young enough to be his grandchildren, and he says he will certainly stick the race out to the end.”

Day Four

On the fourth day, Campana was bringing up the rear among the eight runners still in the race. He claimed he had eaten seven plates of mackerel for breakfast. At 11:50 a.m., with 260 miles, he announced he was retiring from the race. “The strawberry shortcake that he had been dieting upon did him in.”

But Campana was not really out of the race. He continued. “Old Sport, who reconsidered his determination to quit, came on again.” He reached 280 miles by the end of the day, slept all night, and returned to the track as the morning crowd returned. It was believed that he stayed in the race because a man bet money that he would reach 400 miles. “Campana is not bothered with floral tributes, but occasionally some sympathizer will give him a dollar. This, the old man held aloft and waved wildly.”

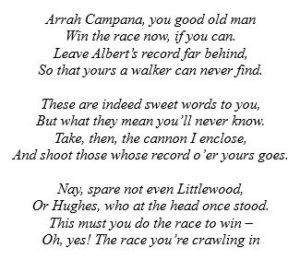

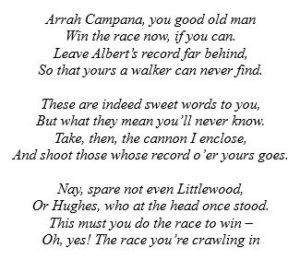

Alarming Package Received

Campana received a mysterious package in the mail that worried him. He had Special Officer Harry Nugent open it. It contained a toy pistol with the name “Daisy” on it. Enclosed was also a poem encouraging him to shoot his competitors in order to win.

Final Days

Staying in the race was certainly worthwhile. “Campana, with an expression of desolation on his wrinkled old face, ran a few laps on the track occasionally, and had picked up about $100 in small bits from tender-hearted and open-handed spectators. He slouched around wagging his head, somewhat disconsolately.” After he was through parading his greenbacks around, stuffed in the buttonholes of his shirt, he would stop at the scorers’ stand and deposit the money to be cared for by Edward F. Plummer (1846-1905), head of scoring. “Campana had no chance for a share in the gate receipts, and the funds he flourished were contributions from the spectators, who seemed to think that the clown of the show should be remunerated in some way. He wears a buttonhole bouquet pinned on this white shirt, a flashy cap and white drawers.”

The evening crowd filled the building, estimated at 10,000 people. “After theater time, the boxes began to fill up with bright-faced women and their escorts, clubmen, and men well-known in Wall Street and political life. The girls in the boxes chewed gum tranquilly, and the men smoked languidly.”

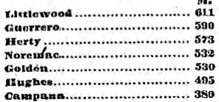

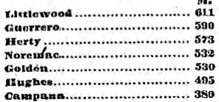

Littlewood won with 611.3 miles. Campana reached 380 miles. It was estimated that he had received $300-$400 in donations from admirers. Near the end of the race he was dressed in his red fireman’s shirt, wearing an old-time fire helmet with No. 41 on the shield. “He ran a couple of laps and the spectators almost went wild with enthusiasm.”

Feeling like he struck gold, Campana returned to Bridgeport, Connecticut. He told everyone that he was feeling first rate and was ready to race again. “He floated down Main Street smoking a good cigar and twirling a dizzy little whip. He was greeted right and left and seemed to enjoy it. He looked well and said he felt better than he looked.”

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part One

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Two

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Three

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Four

Sources:

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 15, Sep 18, 1885, Jun 2, 1888

- The Sun (New York, New York), Mar 17, Oct 1, 11, 1885, Feb 4, May 10, 12, 13, 1888

- The New York Times (New York), Jun 13, 1886, Nov 21, 1887, May 9, 11, 1888

- The New-York Tribune (New York), May 8, 1888

- The Evening World (New York, New York), Feb 4, 6, May 7-12, 1888

- Lancaster Daily Intelligencer (Pennsylvania), Jun 23, 1885

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Connecticut), Jun 24, 1885, Sep 12, 1887, Feb 6, Mar 12, Jun 21, Sep 14, 1888

- The Day (New London, Connecticut), July 29, 1885, Mar 18, Aug 27, 1886, Feb 7, 1888

- The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut), Oct 10, 1885, Feb 23, 1886, Sep 14, 16, 1887

- The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut), Jul 17, 1886, Apr 20, May 11, Jun 19, 1888

- Daily Sentinel (Rome, New York), Nov 1, 1886

- The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut), Sep 15, 1887

- Waterbury Democrat (Connecticut), Dec 29, 1887, Feb 3, 1888

- The Springfield Daily Republican (Massachusetts), Feb 7, 1888

- The Brooklyn Daily Times (New York), Feb 8, May 12, 1888

- Brooklyn Eagle (New York), Apr 2, May 9, 13, 1888

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), May 7, 1888

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), May 7, 1888

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), May 13, 1888

- Sunday Truth (Buffalo, New York), May 13, 1888

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Jun 16, 21, 1888

- The Waterbury Democrat (Connecticut), May 19, Jun 4, Aug 22, 1888

- Transcript-Telegram (Holyoke, Massachusetts), May 19, 1888

- The Springfield Daily Republican (Massachusetts), May 22, 31, 1888

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Oct 18, 1888