Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:21 — 29.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

|

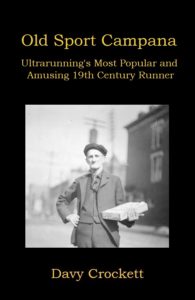

![]()

![]()

Campana published a boxing challenge to the world. “I, Napoleon Campana, alias Old Sport, hereby challenge any man in the world 61 years of age, to fight to a finish, London prize ring rules, for the sum of $500 a side. If this challenge is not accepted, I claim for myself the title of champion of the world.” No one took up the wager, so he must have become the champion boxer of the world. He next issued a challenge to race any man over 60 years in a 100-mile race. Campana was actually 52 years old. It would not have been a fair race.

It September 1889, Campana announced that he was in training for his “farewell race in America,” a six-day twelve-hours-per-day race to be held at the Polo Rink in New Haven, Connecticut. Would it really be the last race of his career? He was asked how he made a living. He replied, “I don’t work for a living young feller.” He demanded $250 from the race manager, James L. Meenan, to start in the race but was refused. He left the rink in disgust.

Campana returned later as a spectator and sent a gift to his Connecticut rival, Alfred Elson (1836-1900), who was in the race and was the same age as Campana. It was a cabbage with $5 rolled inside it. “Elson declined to carry the cabbage around the rink, so Sport stuck it on the end of a board and dogged him around the track, holding the cabbage over Elson’s head.”

The Street Peddler

Skipped a Waterbury Connecticut Race

In January 1890, Campana was asked why he wasn’t competing in a race in nearby Waterbury. He explained that the race director, Maloney, had come to recruit him for the race. He asked Campana what he wanted. “I told him I wanted a suit of clothes, not like the clothes he had on, but a suit to walk in. He said I could have anything I wanted and told me to meet him at the train depot on Monday.” Maloney publicized that Campana would be in the race, but he was a no-show at the train station. “Why that Maloney wanted me to go to Waterbury and advertise his walking match. That was all he cared about. But the fellow knows now that the old man ain’t no fool and won’t spoil his reputation for a few dollars. Yes, mister, Old Sport is poor, but honest.”

Jumping Off a Freight Train

![]()

![]()

Off to Chicago

75-hour Race in Chicago, Illinois

The event was poorly attended and lost money. “Campana’s share of the gate receipts will not be enough to enable him to retire and he will continue to sell chewing gum at so much per chew.” In August 1890, he was spotted still in Chicago, training with George Connor (1863-) of England, who was living in New York City. “The two endeavored to arrange a pedestrian contest in Chicago, in hopes of realizing sufficient funds to enable them to reach home without walking.”

Six-Day Race in Detroit, Michigan

Detroit was an epicenter for several six-day races in 1890. William “Billy” Crawford announced that with a summer’s rest, another six-day race would be scheduled during Detroit’s Exposition week in September 1890. His planned race was backed by “a number of Detroit capitalists.” By August, excitement grew. “In many ways the coming six-day race will be by all odds the most remarkable ever seen in Detroit or anywhere else.”

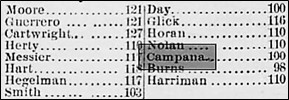

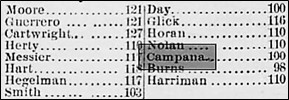

Campana went to Detroit to compete. The day preceding the race, the runners paraded through the city, led by the Detroit Military band, to much fanfare. They were dressed in “natty dusters and hats and carried canes.”

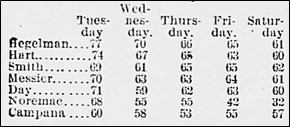

Campana reached 100 miles during the first 24 hours, tied for eleventh place. “He covers ground remarkably well, considering his age and the fantastic garb he wears.” In 48 hours, he reached 175 miles and climbed into seventh place. He was three miles ahead of his training partner, George Connor, who was half his age. He needed to reach 475 miles in order to share in the winnings. Some of his friends from New York City planned to award him with a nice purse of money if he succeeded.

After three days, he reached 253 miles, 35 miles behind the leader, Frank Hart. “Campana made a speech about every three hours. It was the same in every case, and was to the effect that he has defeated seventeen champions and would whip a few more before the race closed.” He climbed into sixth place after the fourth day, with 335 miles. On the fifth day, Campana quit, a rarity for him, after 375 miles. His feet were so sore, he could no longer walk on them. Hart won with only 475 miles.

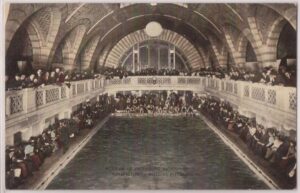

Six-Day Race in St. Louis, Missouri

The race was held in Clark‘s Natatorium, one of the most popular places in the city. It featured a 5,600 square-foot open-air swimming pool, surrounded by spectator seating. It was used for swimming lessons, swimming races, and eventually six-day foot races. During the winters, the Natatorium needed to be used for other attractions, like bicycle and running races. This was the first six-day race held in that building and established the Natatorium as the center place for six-day races during the 1890s.

The Start

Day Two

By the second day, Campana was doing “remarkably well,” in fourth place, with 155 miles in 38 hours, less than twenty miles behind the lead. “The old man took off his walking shoes and trotted around the sawdust ring in his socks and then pulled those off and tried going in his bare feet. His occasional spurts never fail to bring forth applause from the audience. If he should hold out and secure a place, it will break the bookmakers, for tremendously long odds have been laid against him doing so.”

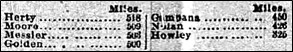

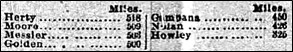

Christmas Day

For excitement, George Cartwright (1848-1928), who had dropped out of the race, came back for a side-show 20-mile race against Peter Hegelman (1864-1944). But before that race, Cartwright went around the building, badmouthing the main event and its manager, Ralph Johnson. “He and Johnson exchanged words and then came to blows. In the scrimmage, the long-distance runner had his eyes blacked, and he was ejected from the building.”

The Final Days

On the fifth day, Campana continued to work hard in fifth place. He was at a serious disadvantage compared to the other runners. “The old man had no trainer and not even a tent in which to sleep. Some boys had fun with him and gave him a little more beer than he should have taken, in his exhausted condition. Sport became even more talkative than usual and, in every lap, would make several stops to talk to the crowd. He also sang his celebrated song about Sullivan. His work is really phenomenal for a man of 62 years of age (actually 54).”

Campana stayed around after the race. “The old man had taken considerable St. Louis beer aboard and was very enthusiastic on the subject of St. Louis and St. Louisans. Instead of going to a hotel, he slept in the cot that had been used by Manager Johnson and stayed there until morning when he was sent to a hotel.”

About 17,000 people watched the race during the week. The race was a financial success for Manager Johnson, who made a profit of $2,000, although he received criticism for broken financial promises. Campana did not receive anything from the race. “He probably got more money thrown to him by the crowd than any of the contestants. If he had not gotten drunk, the old man would undoubtedly have done much better. He sent $175 home to his wife, Jennie, at Bridgeport, Connecticut, as a Christmas gift, and it is believed that he had about $500 thrown to him by the people. That was probably why the old man thought St. Louis was the greatest place on earth.”

Six-Day Race in Minneapolis, Minnesota

There was no long rest for Campana. He quickly made his way to Minnesota for the next six-day race to be held just four weeks later. Minneapolis became a hotbed for pedestrianism and would put on at least five six-day races in the coming years, and Campana made a deep impression on the city. Several prominent runners, including Frank Hart (1856-1908), Norman Taylor (1830-1911), Gus Guererro (1854-1914), would make the city their new home.

The race was scheduled for the large Washington Rink. It was thought to be the largest skating rink in America at that time, but recently had not been used as much, except for political speeches. A couple of weeks before the event, carpenters began the transformation of the rink into a pedestrian arena. “The clang of carpenters’ hammers and the nerve-tearing screeching of a dozen workmen’s saws have set the old building’s heart to throbbing again, and for a week anyway, the ‘good old days’ will be restored.” Campana made his training headquarters in nearby St. Paul until the rink was ready to be run in.

Campana Promotes Himself

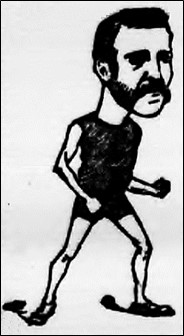

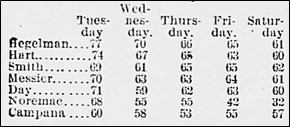

“For the last fifteen years Campana has been a funny card in six-day matches. He was the circus end of the walks contested at Madison Square Garden. He is a little, comical looking man, with a deep valley in his face under his cheek bones, and a big chin and nose so near each other that Mr. Campana is in danger of having them singed if he smokes a cigar more than halfway down. He wears four-days’ old whiskers and is a plain dresser. He might be 35 years old, or 50, or 60. He says he was born 62 years ago.”

Campana was interviewed at a downtown restaurant and had no problem talking about himself. “I’m a dead-game ‘Sport’ and wouldn’t sell my reputation for $50,000. Why, they talk about me in Egypt. I have made 75,000 miles in 30 years.” He showed the reporters all the tattoos on his body, including the name of his wife, Jennie Dalton Campana. “She is my wife. I think a good deal of her. She used to train me in my big matches. I am poor and respectable. I’m a hustler from Hustlerville, and if I didn’t make so much noise about myself, you never would hear of me.”

On the day before the race, all the runners were resting except for Campana, “who continued to shatter the atmosphere with his arms and tell everybody he chanced to meet that he had been acquainted with every man with a drop of sporting blood in his veins since the days of Yankee Sullivan.”

The Start

Day Two

On the second day, Campana still looked fresh. “He talked to everyone, ‘roasted’ his attendants, and pleased the crowd fully.” Other times, he sang songs for the crowd. He received a telegram from President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) that read, “Make 500 miles and I will give you a lifelong job in the lighthouse in Chicago.” Campana claimed that when he was a schoolteacher, Harrison was a student in his school. (Strange, because Harrison was three years older than Campana). He also received a telegram from his hero, boxer, John L. Sullivan (1858-1918), who wrote: “Make 500 miles and I will give you $500 and pay your travel expenses back to Boston.” Campana read that telegram from a chair in the center of the rink and received huge applause.

Day Three

On the third evening, Campana was one of the center attractions. “One of the features was the singing of a song by Old Sport Campana, who caught the audience just right. The old-timer seemed pretty fresh and followed up his song by making a spurt. He declared that he intended to be ‘in at the death.’”

Remaining Days

As the race neared its conclusion, it was written, “Old Sport Campana was on the track more than any man in the race. He made lots of sport for the spectators yesterday. He gathered in a pocketful of silver dollars too. Three admirers gave him $10 each, while several gave him $50. He certainly is a character. Those who have ever seen him will never forget him. He is alone worth the price of admission.” On the closing night, he climbed up on the judges’ stand and sang a song about Sullivan. He received applause for five minutes and the race manager gave him $25 of gold.

![]()

![]()

Six-Day Race in St. Paul, Minnesota

The audience eagerly awaited his performance and self-aggrandizing pronouncements. “Some people may have imagined that yesterday’s windstorm was the result of atmospheric disturbances. Not so. It was all attributable to the fact that on the morning train. Old Sport Campana blew in to take his place on the sawdust track at the Arcade in the six-day race. With a wild whoop, as he passed out of the Union depot doors, Old Sport declared that he was a sure winner of the race. ‘Some of these ducks think I’m not in it. I’ll show ‘em that Sport is on deck yes. I’ll bet any part of a $1,000 that I’m as good as third at the finish.’

The race began on February 24, 1891. Campana did well on the first 12-hour day, reaching 60 miles, in eighth place. “Campana, in whose attenuated frame there lies concealed more of the vigor of youth than would seem possible, kept going in his peculiar gait, a cross between that of a lame dog and a strunghalt mule, but got over the grounds surprisingly. Here is a man sixty-two odd years old, holding his own with the young ones in creditable style. His method of locomotion is entirely the reverse of graceful, but it counts, and Old Sport swears he will be in at the death.”

Campana finished with 323 miles in sixth place. The race management admitted that he was paid a salary. All the runners spoke very highly of how the race was conducted.

Peddling in Chicago

A month later, in April 1891, it was reported that Campana was peddling chewing gum around sporting resorts in Chicago, Illinois. Gum was becoming more and more popular. William Wrigley Jr. (1861-1932) entered the business with his famous gums. False reporting stated that Campana had been greatly failing and was “a wreck of his former self.” Chicago didn’t understand that he always went back to his peddling once his race season was over and always looked like a wreck.

Race from Chicago to Omaha

In May 1891, C. J. Stephens, “a long-distance pedestrian” was hired by the Chicago Herald to walk 500 miles from Chicago to Omaha, Nebraska, in nine days to advertise the newspaper. He was promised $1,000 if he succeeded. Another company, a wet goods house in Chicago, got in the game and sponsored Campana to beat Stephens. “Stephens was joined by Old Sport Campana, dressed in gaudy colored tights and wearing upon his card the words, ‘The House of David.’ The two were racing and Campana was confident he would win.

The plan was to walk on railroad tracks the entire way. The first 75 miles were accomplished in 19 hours. “Stephens tried to get away from Campana, but the elderly person had a watch placed in his room and whenever his younger foeman tried to get away in the night, he found a tottering shadow following him.” After a couple days Campana was close on the heels of Stephens “who is doing some tall hustling to hold his own with the time-worn pedestrian.” Stephens kept Campana in his sight until mile 77, when Old Sport pressed far ahead.

“Shortly after 9 a.m. on May 19, 1891, a slender, wiry-built, elderly man, with black tights and a red cap, hurried off the Council Bluffs bridge, and followed by a crowd of spectators, made for a saloon.” Campana completed the 500-mile journey in eight days and twenty-two hours. “Old sport, when he arrived, he was tolerably well-pickled in whisky, which he had drunk to keep him up on the way. He drank an enormous amount and attributes his success to that factor largely.” Stephens had stumbled on a railroad trestle in Iowa, sprained an ankle, and had to give up the race. He came in by train.

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part One

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Two

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Three

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Four

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Five

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Six

- Old Sport Campana (1836-1906) – Part Seven

Sources:

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Jul 6, Oct 26, 1889

- The Waterbury Democrat (Connecticut), Jul 11, 1889, Jan 4, Feb 20, Aug 2, 1890

- The Morning Journal-Courier (Connecticut), Sep 14, 1889

- The Meriden Daily Republican (Connecticut), Sep 19, 1889, Jan 20, 1890

- The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut), Sep 23, 30, Oct 21, 1889, Mar 10, Apr 10, Aug 2, 1890

- The Day (New London, Connecticut), Sep 23, 1889

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Sep 1, 1889

- The Brooklyn Daily Times (New York), Sep 7, 1889, May 22, 1890

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), May 26, 1889

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), May 22, 1890

- The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), May 22, 1890

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), May 24-25, Dec 23, 1890

- The Champaign Daily Gazette (Illinois), May 26, 1890

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Aug 30, Sep 2-6, 1890

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Dec 22-29, 1890

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Dec 23, 1890

- The Minneapolis Journal (Minnesota), Jan 6, 1891

- Minneapolis Daily Times (Minnesota), Jan 18-19, 28-30, Feb 2, Mar 2, 1891

- Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Jan 22, 27-28, 31, 1891

- The Saint Paul Globe (Minnesota), Jan 26-28, Feb 22-28, Mar 4, 1891

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Mar 30, 1891

- Grand Rapids Herald (Michigan), Apr 3, 1891

- Wilkes-Barre Times Leader (Pennsylvania), May 13, 1891

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), May 14, 1891

- The Buffalo Times (New York), May 16, 1891

- The Sioux City Journal (Iowa), May 17, 1891

- Evening World-Herald (Omaha, Nebraska), May 19, 1891

- Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), May 19-20, 1891

- The Lincoln Evening Call (Nebraska), May 20, 1891