Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:19 — 32.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

Pam Reed, age 61 in 2022, from Jackson Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona, is a 2022 inductee in the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame, its 21st member. Over the years she has been a prolific, successful runner, especially in desert races in the western United States.

Pam Reed, age 61 in 2022, from Jackson Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona, is a 2022 inductee in the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame, its 21st member. Over the years she has been a prolific, successful runner, especially in desert races in the western United States.

Pam (Saari) Reed (1961-) grew up in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, in the small mining town of Palmer. She is the daughter of Roy E. Saari (1932-2018) and Karen H. Peterson (1935-2014). Her father worked at an enormous open pit iron mine in town and was always on the go. Her mother was a nurse who instilled in her daughters “the values of initiative and assertiveness,” and was active in outdoor sports such as snowmobiling and cross-country skiing.

Pam has Scandinavian ancestry: Finish on her father’s side, Norwegian and Swedish on her mother’s side. Her grandfather Leonard D. Peterson (1895-1972) was a man of determination who worked two full-time jobs, for the railroad and the Chicago Transit System. Once he walked all the way from Merrill, Wisconsin to Chicago, about 300 miles.

| Get Davy Crockett’s new book, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim History. The trails, bridges, early daring canyon crossers. Enhance your Rim-to-Rim experience. |

Early Years

As a youngster, Pam, with her competitive nature, would enjoy challenging the boys in races and games. She had dreams of competing in the Olympics in gymnastics, but she became better at tennis. At the age of fifteen, she started running to get into shape for tennis

As a youngster, Pam, with her competitive nature, would enjoy challenging the boys in races and games. She had dreams of competing in the Olympics in gymnastics, but she became better at tennis. At the age of fifteen, she started running to get into shape for tennis

Pam attended Negaunee High School, about ten miles away, and was very active in sports and activities including track, tennis, gymnastics, cheerleading and choir. On the high school track team, she didn’t like the long three-mile runs because they were boring, and she would lead her friends cross-country across backyards to cut down the distance.

Pam attended Negaunee High School, about ten miles away, and was very active in sports and activities including track, tennis, gymnastics, cheerleading and choir. On the high school track team, she didn’t like the long three-mile runs because they were boring, and she would lead her friends cross-country across backyards to cut down the distance.

Negaunee is the home of the Suicide Ski Jump facility and a luge track. Winter sports were an important part of the region where Pam grew up, although she didn’t especially enjoy skiing, because she didn’t like the cold. She remembered, “I grew up skiing. My dad would take me skiing and I didn’t like going. I was five years old and there was tons of really heavy snow, and I broke my leg.” She didn’t know it then, but she was destined for the desert.

Hard work was in her blood. She said, “Physical toughness was a strong point in my family, and maybe in the Upper Peninsula as a whole. It was cultivated and bred into us over many generations, so it came easily to us. It was expected of us, and it was what we expected of ourselves.”

Hard work was in her blood. She said, “Physical toughness was a strong point in my family, and maybe in the Upper Peninsula as a whole. It was cultivated and bred into us over many generations, so it came easily to us. It was expected of us, and it was what we expected of ourselves.”

For college, Pam attended Michigan Tech in the remote town of Houghton, Michigan, about 90 miles away, where she continued to compete in tennis and excelled. She majored in Business and later transferred to Northern Michigan University in Marquette. She soon married her high school boyfriend, Steve Koski. They moved to Tucson, Arizona where Pam transferred to the University of Arizona to complete her college education and she eventually received a Bachelor of Science in Business.

Pam became an aerobics director at a Tucson health club and started to compete in triathlons in 1989 at the age of 28. She also started running marathons. (She would eventually run more than 100 marathons, with 2:59:10 at the 2001 St. George Marathon as her personal best.)

Pam had two young sons, but her marriage to Steve ended in divorce. She soon married Jim Reed, an accountant, who also competed in Ironmans. He also had two sons.

Becoming an Ultrarunner

In 1991, a friend, Bennie Linkhart (1931-2017), age 60, gave Jim a copy of Ultrarunning Magazine. Bennie was a state weightlifting champion who had taken up running and was training to run Leadville 100. When Jim introduced Pam to Bennie, she thought, “Who in the heck runs 100 miles? No one can do that.”

When Pam read the magazine, she became excited. Bennie urged both Pam and Jim to try ultrarunning and took Pam on training runs in the canyons above Tucson. She said, “He became my mentor, and I would talk to him, and I would run with him. He really inspired me to do a lot, and to get into 100-mile runs.”

Pam and Jim signed up for their first ultra, Elkhorn 100K in Helena, Montana and trained in Jackson, Wyoming. Jim said, “Since neither of us really knew what we were getting into, we made a pact to stay together for the whole race.” They finished dead last, in 14 or 15 hours. (Pam would later win this race four consecutive years.)

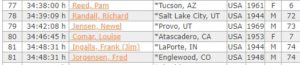

With that initial success, or survival, they both ran in the 1992 Wasatch Front 100. Jim DNFed about mile 60 and Pam went on to finish in the back of the pack with 34:38. That began her love for running the 100-mile distance and since then, she has finished at least one 100-miler every year. The following year she won her first ultra, the Old Pueblo 50, in 8:11:04, held near Tucson in the Santa Rita Mountains.

With that initial success, or survival, they both ran in the 1992 Wasatch Front 100. Jim DNFed about mile 60 and Pam went on to finish in the back of the pack with 34:38. That began her love for running the 100-mile distance and since then, she has finished at least one 100-miler every year. The following year she won her first ultra, the Old Pueblo 50, in 8:11:04, held near Tucson in the Santa Rita Mountains.

Pam quickly excelled in ultras and more wins came. (She would go on to win at least 30 ultras as of 2022.) She won her first 100-miler in Tucson in 21:30:00 and broke 20 hours with a win at 1998 Old Dominion. She completed the Grand Slam of ultrarunning that year, becoming the twelfth woman to finish four classic 100-milers in one calendar year. Her combined time is still the ninth best in history among the women. In her ultra career, she achieved 13 wins in races of 100 miles or more and at least 45 podium finishes in 100-milers.

Pam quickly excelled in ultras and more wins came. (She would go on to win at least 30 ultras as of 2022.) She won her first 100-miler in Tucson in 21:30:00 and broke 20 hours with a win at 1998 Old Dominion. She completed the Grand Slam of ultrarunning that year, becoming the twelfth woman to finish four classic 100-milers in one calendar year. Her combined time is still the ninth best in history among the women. In her ultra career, she achieved 13 wins in races of 100 miles or more and at least 45 podium finishes in 100-milers.

The Tucson Marathon

In the early 1990s, Jim Reed was the treasurer for the Tucson chapter of the Road Runners Club of America. They had held a small marathon in which Pam placed second in 1993. But when it wasn’t held in 1994, Pam took over the Tucson Marathon and became its race director for 1995. She said, “I kept thinking that it would be really cool to have a downhill marathon in Tucson. I had just run an article in Runners World on the downhill marathon in St. George, Utah. Every year for nearly 30 years I had to change the course.” With the help of others, it grew into a prominent, massive marathon of nearly 5,000 participants. She finally retired and sold the marathon in 2022 to Aravaipa Running.

In the early 1990s, Jim Reed was the treasurer for the Tucson chapter of the Road Runners Club of America. They had held a small marathon in which Pam placed second in 1993. But when it wasn’t held in 1994, Pam took over the Tucson Marathon and became its race director for 1995. She said, “I kept thinking that it would be really cool to have a downhill marathon in Tucson. I had just run an article in Runners World on the downhill marathon in St. George, Utah. Every year for nearly 30 years I had to change the course.” With the help of others, it grew into a prominent, massive marathon of nearly 5,000 participants. She finally retired and sold the marathon in 2022 to Aravaipa Running.

2002 Badwater 135

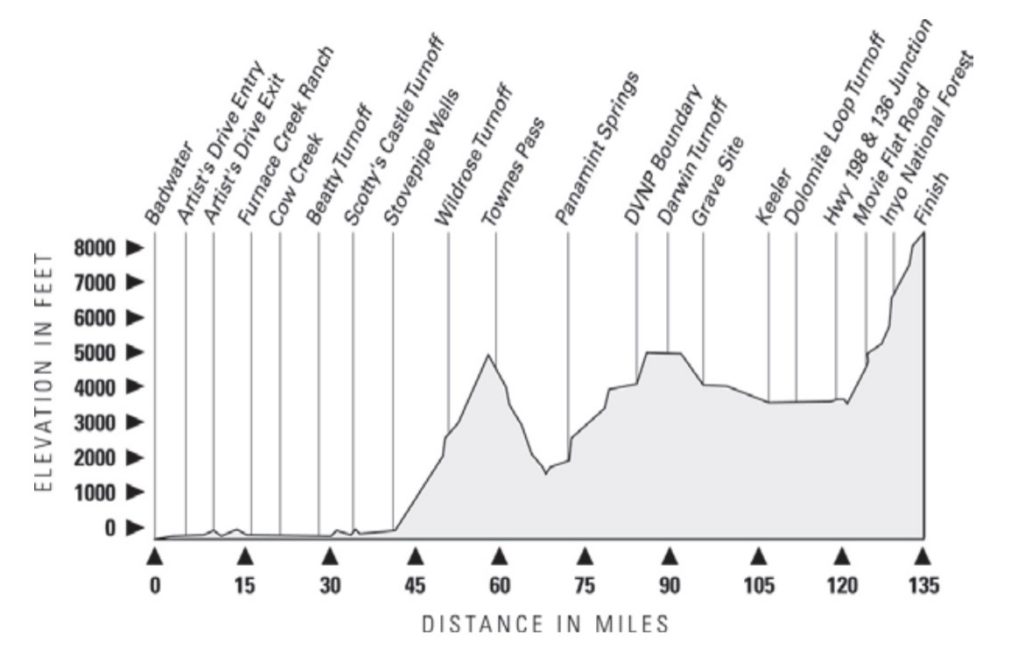

Beginning in 1966, runners started to have a fascination with running across Death Valley in the heat of the summer. In 1987 the first formal Badwater race was organized running from the low point of the U.S. to Mount Whitney. Living in Arizona, Pam was used to running in temperatures over 100 degrees and in 2002 wished to give the famous Badwater Ultramarathon (135 miles) a try in Death Valley. She said, “I love to race in the heat. I think that gives me a big advantage. At home in Tucson, I’m used to running for three hours every day in temperatures of around 100 degrees.”

Beginning in 1966, runners started to have a fascination with running across Death Valley in the heat of the summer. In 1987 the first formal Badwater race was organized running from the low point of the U.S. to Mount Whitney. Living in Arizona, Pam was used to running in temperatures over 100 degrees and in 2002 wished to give the famous Badwater Ultramarathon (135 miles) a try in Death Valley. She said, “I love to race in the heat. I think that gives me a big advantage. At home in Tucson, I’m used to running for three hours every day in temperatures of around 100 degrees.”

For her first Badwater in 2002, there were 79 runners, 63 men and 16 women. (race video). With already twenty 100-mile finishes, she was not the typical Badwater rookie. She started at 6:00 a.m. and it was already over 90 degrees. She said, “My plan was to just keep going as steadily as possible. I wasn’t going to stop unless I had to throw up. . . I just remember the awesome crew running or biking along with me, telling me stories to keep me entertained, spraying me down with water to keep me as cool as possible.” Using a spray bottle was a new technique her crew came up with that year, that others soon copied.

Pam ran on “automatic pilot,” following after her van and ticking off the miles. With about 40 miles to go the race director drove up and told her crew that she was comfortably in the lead with the staggered starts. Pam had just been trying to do well and was stunned by the news. She shifted from just being a participant to a true competitor.

Pam ran on “automatic pilot,” following after her van and ticking off the miles. With about 40 miles to go the race director drove up and told her crew that she was comfortably in the lead with the staggered starts. Pam had just been trying to do well and was stunned by the news. She shifted from just being a participant to a true competitor.

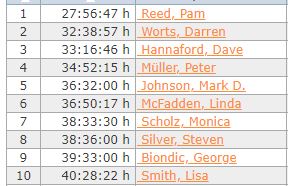

Pam went on, becoming the first woman ever to win Badwater overall, with a time of 27:56:47, and also a women’s course record. Her accomplishment made the front page of the Los Angeles Times the next day.

“Crossing that tape was like dying and being born at the same time. I was literally crying, just letting out all the tension. Though I had managed not to focus on it, I had been scared throughout much of the race—it was so brutally hot, and I didn’t know what was going to happen to my body. Now all I wanted was to sit down. There were a few folding lawn chairs and I just about fell into one of them. People were asking me all kinds of questions, and for once, Motormouth could barely get out two words.”

“Crossing that tape was like dying and being born at the same time. I was literally crying, just letting out all the tension. Though I had managed not to focus on it, I had been scared throughout much of the race—it was so brutally hot, and I didn’t know what was going to happen to my body. Now all I wanted was to sit down. There were a few folding lawn chairs and I just about fell into one of them. People were asking me all kinds of questions, and for once, Motormouth could barely get out two words.”

2003 Badwater 135

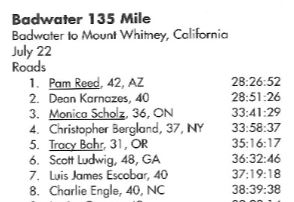

Pam ran Badwater again in 2003. (video). Pam’s win the previous year made such a news splash that many mainstream media outlets came to the race including CNN, ESPN, CBS, Associated Press and others.

Pam ran Badwater again in 2003. (video). Pam’s win the previous year made such a news splash that many mainstream media outlets came to the race including CNN, ESPN, CBS, Associated Press and others.

The night before the race, she was told that Dean Karnazes was running. She had never heard of him before but was told about his recent accomplishments and fame. Many of the runners wore white suits that looked like biohazard suits. Pam did not, but at time used knee-high stockings filled with ice which she draped over the back of her neck.

For this year, she started in the latest stage at 10 a.m., with the faster runners, when it was 110 degrees. Several men went out fast and by mile 17, Pam was in fourth place. The day was extremely hot, pressing toward 130 degrees with scalding winds.

With the staggered starts, Pam passed runner after runner. At Panamint Valley, she was in second place, although Karnazes was gaining on her. At that point she wasn’t feeling well, falling apart, but pressed on. Karnazes started to have a tough time too.

With the staggered starts, Pam passed runner after runner. At Panamint Valley, she was in second place, although Karnazes was gaining on her. At that point she wasn’t feeling well, falling apart, but pressed on. Karnazes started to have a tough time too.

After dawn, about mile 111 at 6:47 a.m., she went into the lead, passing Chris Bergland, who shook her hand as she passed. With Pam out of sight, the men concentrated on racing for second place. But Pam and her crew knew that Karnazes not far behind. She attacked the final climb, winning by 25 minutes to again be the overall Badwater champion with a time of 28:26:52.

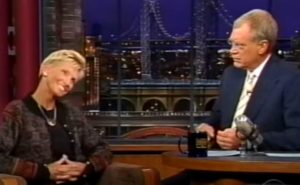

After her second Badwater win, Pam made a classic appearance on the David Letterman Show. Dave asked, “What do you win for your efforts?” Pam replied, “You get a belt buckle.” Dave jokes, “Well good Lord, sign me up. Where do I get in this, a new belt buckle, are you kidding me? What’s it like running at night.” She replied, “It’s kinda fun, you have a flashlight, and you just keep running.” Dave quipped what he thought was a joke, but was actually truth, “You just keep thinking of that belt buckle.”

After her second Badwater win, Pam made a classic appearance on the David Letterman Show. Dave asked, “What do you win for your efforts?” Pam replied, “You get a belt buckle.” Dave jokes, “Well good Lord, sign me up. Where do I get in this, a new belt buckle, are you kidding me? What’s it like running at night.” She replied, “It’s kinda fun, you have a flashlight, and you just keep running.” Dave quipped what he thought was a joke, but was actually truth, “You just keep thinking of that belt buckle.”

Yes, Pam was the Badwater champion and that bothered some of the male runners. “The year after that, the guys got serious about beating me—or so I heard. There were all these rumors about how they were training—for the race in general, yes, but the subtext was that they were going to take out Pam Reed. Except for the added pressure, I found this funny—even flattering.” The next year, she had a tough year, but still finished fourth and Karnazes won.

Yes, Pam was the Badwater champion and that bothered some of the male runners. “The year after that, the guys got serious about beating me—or so I heard. There were all these rumors about how they were training—for the race in general, yes, but the subtext was that they were going to take out Pam Reed. Except for the added pressure, I found this funny—even flattering.” The next year, she had a tough year, but still finished fourth and Karnazes won.

She continued to have a long association with Badwater, where she finished 11 times, all podium finishes with two overall wins, three women’s wins, and seven second places.

Fixed-Time Racing

After Pam won her second Badwater, future hall-of-famer, Roy Pirrung, the captain of the U.S. 24-Hour team invited her to compete at the 2003 24-hour world championship race in the Netherlands. In her first 24-hour competitive race, with only a few months’ training for it, she reached 134 miles, on a road loop. She was the top U.S. woman and sixth among all the women. Three weeks later she ran in a track 24-hour race in San Diego and broke the American women’s 24-hour record with 138.96 miles running on a 400-meter track.

After Pam won her second Badwater, future hall-of-famer, Roy Pirrung, the captain of the U.S. 24-Hour team invited her to compete at the 2003 24-hour world championship race in the Netherlands. In her first 24-hour competitive race, with only a few months’ training for it, she reached 134 miles, on a road loop. She was the top U.S. woman and sixth among all the women. Three weeks later she ran in a track 24-hour race in San Diego and broke the American women’s 24-hour record with 138.96 miles running on a 400-meter track.

For her amazing 2003 achievements, she was named the 2003 USA Track & Field Women’s Ultra Runner of the Year, and the 2003 Competitor Magazine Endurance Sports Athlete of the Year

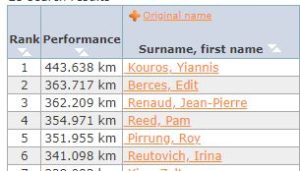

In 2004, at age 43, she was invited to compete at the International 48-Hour Track Championship at Surgeres, France that included legendary Yiannis Kouros of Greece.

“The dirt track ran for less than a quarter mile around a fenced-in area, within which there were lots of parties going on. People were eating, drinking, cooking hot dogs, and everyone was smoking.” With her family crewing her, Pam finished as the top American, fourth overall, reaching 220 miles (354.9 km), beating Pirrung by 3 km. She also broke the American age group record (W40-44) which she still holds in 2022.

In November 2004, Pam continued to travel, and competed in the 2004 24-hour world championship race at Brno, in the Czech Republic, on an asphalt 2.5 km road loop. “The course was outdoors, on sidewalks that wound all over—lots of twists and turns, up a small hill, past what looked like housing projects, past a parking lot. It was a bit on the crazy side. And wouldn’t you know it, it rained.” Pam placed seventh, with 132 miles.

About competing, Pam said, “I don’t think about other runners when I’m in an event. When I first started running, I always assumed someone else would win, and I didn’t worry very much about who that might be. When I became good enough that I might be the winner, I was too focused on the technical side of my own performance to think about the competition.”

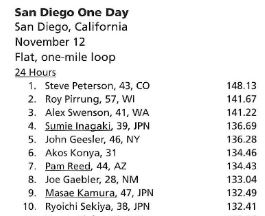

In 2005, Pam competed in the American 24-hours National Championship held in Mission Bay, near San Diego California. The field was stacked with many of the great 24-hour runners in the country along with world greats from Japan. A road one-mile rectangular loop course was used that was not fast. They never changed directions. About 100 runners were entered. With all the runners constantly around her, it became a highly competitive race in her mind, worrying about the others rather than concentrating on herself. She stopped only twice during the entire race, both times to get a quick massage, for a total of 3.5 minutes of down-time.

In 2005, Pam competed in the American 24-hours National Championship held in Mission Bay, near San Diego California. The field was stacked with many of the great 24-hour runners in the country along with world greats from Japan. A road one-mile rectangular loop course was used that was not fast. They never changed directions. About 100 runners were entered. With all the runners constantly around her, it became a highly competitive race in her mind, worrying about the others rather than concentrating on herself. She stopped only twice during the entire race, both times to get a quick massage, for a total of 3.5 minutes of down-time.

After about 20 hours, she moved into the lead among the American women, passing a woman who she had been chasing all day and started to stretch out a lead of multiple miles. She finished 134.4 miles, winning the national championship, about two miles less than a Japanese woman. It was the first time Pam had truly competed hard against specific people for an entire 24 hours.

After about 20 hours, she moved into the lead among the American women, passing a woman who she had been chasing all day and started to stretch out a lead of multiple miles. She finished 134.4 miles, winning the national championship, about two miles less than a Japanese woman. It was the first time Pam had truly competed hard against specific people for an entire 24 hours.

300-Mile Run

In October 2004, Dean Karnazes, the famed “ultramarathon man” ran 262 “continuous miles” in 75 hours, breaking a Guinness Book record for the stunt. This type of run was first popularized by New Zealander, Max Telford, who in 1974 got his name in the book by running 131 miles in 22.6 hours. (Record seekers were allowed to stop five minutes each hour.) In 1976 Telford raised the record to 134 miles in 21 hours running around the perimeter of Oahu, Hawaii. Actually, 19th century runners (pedestrians) went far further doing such continuous running without sleep during six-day races, but also used strong stimulants and cruel crew methods to keep them going.

In 2004, Karnazes blew away all past modern-day “continuous” records by reaching 262 miles. The mainstream media was fascinated by the “record.”

This effort inspired Pam to also give it a try too. She wasn’t really trying to upstage Karnazes, but thought she could go further and longer on a flat road, northwest of Tucson, going back and forth between Marana on the south to Picacho Peak on the north, for a 25-mile loop. She set her target for 300 miles.

Pam began on March 23, 2005, at 6 a.m. “I was caught up in the excitement of all the supporters around me. There had been a piece in the Tucson paper’s sports column about the run, and throughout the day people showed up to watch, crew, or just cheer me on. It was really cool.” She covered the first 50 miles in 8 hours. Many different people ran with her, handing her food and drink. Her mom cooked for her, and her dad took shifts driving the support van. People driving on the freeway would honk their horns as they drove by. A friend drove by, stopped to say hi, mentioning that he was heading to San Diego. When he drove back a couple days later, he again stopped by, and Pam was still running.

Pam began on March 23, 2005, at 6 a.m. “I was caught up in the excitement of all the supporters around me. There had been a piece in the Tucson paper’s sports column about the run, and throughout the day people showed up to watch, crew, or just cheer me on. It was really cool.” She covered the first 50 miles in 8 hours. Many different people ran with her, handing her food and drink. Her mom cooked for her, and her dad took shifts driving the support van. People driving on the freeway would honk their horns as they drove by. A friend drove by, stopped to say hi, mentioning that he was heading to San Diego. When he drove back a couple days later, he again stopped by, and Pam was still running.

Things went relatively well until the third day after mile 250. Pam started to feel weak. She had been forgetting to eat and her tired crew had lost focus going into the third night, evidently forgot to feed her too. Toward the end, she was managing 20-minite-miles. The last 25-mile loop took her more than nine hours. She said, “It was scary for a while. I couldn’t quite think clearly.” She finished with her youngest son, Jackson pacing. The official distance was 301.08 miles in 79:57. Sitting in a chair at the finish, she said, “I’m amazed I did it, but I’m more amazed at how good my body feels. I’ve hurt more after a marathon.” The next day, she flew to New York and was on The Tony Danz Show.

Things went relatively well until the third day after mile 250. Pam started to feel weak. She had been forgetting to eat and her tired crew had lost focus going into the third night, evidently forgot to feed her too. Toward the end, she was managing 20-minite-miles. The last 25-mile loop took her more than nine hours. She said, “It was scary for a while. I couldn’t quite think clearly.” She finished with her youngest son, Jackson pacing. The official distance was 301.08 miles in 79:57. Sitting in a chair at the finish, she said, “I’m amazed I did it, but I’m more amazed at how good my body feels. I’ve hurt more after a marathon.” The next day, she flew to New York and was on The Tony Danz Show.

She was interviewed by many news outlets. Her common statement was, “This was the highlight of all the running I’ve done. This was the hardest run I’ve ever done, but it was also the best experience.” She was especially grateful for her family and friends who crewed her during those three days and nights. Thinking for her father’s Finish ancestry, she said, “There’s a Finnish word, sisu, that means “guts.” That’s a part of my heritage that I try to live up to.”

In ultrarunning circles her success strengthened the idea that some had, that she had a rivalry with Karnazes, and that rivalries were somehow bad for the sport, a form of grandstanding. She tried to make things clear, “I don’t’ do what I do to get attention for myself. Nobody loves publicity enough to run for 80 hours without sleep.” The author of an article in a national magazine tried to invent a story that Pam was obsessively jealous of Karnazes’ fame and that a feud had developed. It wasn’t true. Regarding supposed stalking of Karnazes’ “continuous running” record, today people are always trying to improve fastest know times (FKTs), no matter who sets them. It makes you wonder if she received criticism at that time because she was a woman. She was focused on showing what a woman could do. It truly was amazing to see a woman ultrarunner receive the over-due national exposure that Pam received for both her Badwater wins and her 300-mile run. It was good for the sport and inspirational to women to get into it.

Sri Chinmoy Six-Day Race

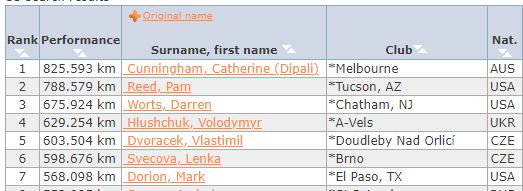

Pam had proven her ability to pile up mega miles across multiple days. In 2009, at the age of 48, she ran in her first and only six-day race on a road loop at Flushing Meadows, Corona Park, in Queens New York. She went there in hopes to break the six-day road world record of 510 miles held by Dipali Cunningham,50, of Melbourne, Australia, a very experienced multi-day runner on the Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team who was also running in the race.

Pam had proven her ability to pile up mega miles across multiple days. In 2009, at the age of 48, she ran in her first and only six-day race on a road loop at Flushing Meadows, Corona Park, in Queens New York. She went there in hopes to break the six-day road world record of 510 miles held by Dipali Cunningham,50, of Melbourne, Australia, a very experienced multi-day runner on the Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team who was also running in the race.

Pam recalled, “Here we were out there doing it, and we killed each other in the first 24 hours, We did way too many miles. So, then we both backed off and then we both came back, and she beat me by twelve miles the last day. I kept asking ‘what do I need to do to get the American record?’ I remember going around and around asking, ‘Am I going to do it? Am I on it?’ That’s what kept me going, and I did it.”

Pam placed second overall and raised the women’s American six-day record to 490 miles, which she still held in 2022. (The previous record was 487 miles set by Donna Hudson in 1987). In this race Cunningham raised the road six-day world record to 513 miles. (The track six-day record was and still is 549 miles held by Sandra Barwick in 1990).

Pam placed second overall and raised the women’s American six-day record to 490 miles, which she still held in 2022. (The previous record was 487 miles set by Donna Hudson in 1987). In this race Cunningham raised the road six-day world record to 513 miles. (The track six-day record was and still is 549 miles held by Sandra Barwick in 1990).

To understand the significance of Pam’s American Record, you need to understand that during the six-day race glory days of the 19th century, only a few American women went over 400 miles in six days and no women during those decades in more than 50 races came close to the distance that Pam achieved on a certified course.

To understand the significance of Pam’s American Record, you need to understand that during the six-day race glory days of the 19th century, only a few American women went over 400 miles in six days and no women during those decades in more than 50 races came close to the distance that Pam achieved on a certified course.

The race made a deep impact on Pam. “That is when I decided I wanted to run across America because it just felt like a job to me. I went to sleep for two hours; I got up and I ran. I just kept doing that and it felt like I could do that forever.”

Mountain 100-milers

With all her achievements and records on roads and track, Pam’s true love has been running on the mountain trails. She has had goals to finish three of the classic 100-milers ten times, Western States, Wasatch Front, and Leadville. At age 61 in 2022, that goal has likely slipped away, but she has finished Wasatch Front 100, fourteen times, with two second place finishes, Western States 100 seven times, and Leadville 100 six times with four top-ten finishes. In addition, she finished two Hardrock Hundreds, both in the top ten, and four Arrowhead Winter 135s with two wins.

With all her achievements and records on roads and track, Pam’s true love has been running on the mountain trails. She has had goals to finish three of the classic 100-milers ten times, Western States, Wasatch Front, and Leadville. At age 61 in 2022, that goal has likely slipped away, but she has finished Wasatch Front 100, fourteen times, with two second place finishes, Western States 100 seven times, and Leadville 100 six times with four top-ten finishes. In addition, she finished two Hardrock Hundreds, both in the top ten, and four Arrowhead Winter 135s with two wins.

When asked why a desert runner who hated the cold wanted to run Arrowhead in Minnesota in the dead of winter, Pam replied, “I liked the idea that it was the coldest place in the U.S. so I thought, I should be able to do this. I thought I needed a different challenge. It has a really cool vibe. It feels like the original ultrarunning to me, like old-time ultrarunning.”

When asked why a desert runner who hated the cold wanted to run Arrowhead in Minnesota in the dead of winter, Pam replied, “I liked the idea that it was the coldest place in the U.S. so I thought, I should be able to do this. I thought I needed a different challenge. It has a really cool vibe. It feels like the original ultrarunning to me, like old-time ultrarunning.”

In 2015, Pam finished in the same year, Western States 100, Hardrock 100, and Badwater 135, all three in just 33 days, the first and still the only person to accomplish that.

In 2019 she became aware that she had 85 100-mile race finishes and set an ambitious goal to soon reach 100 finishes. Her 100th finish came on February 3, 2021, at Grandmaster Ultras in Arizona, just three weeks before her 60th birthday. She became the 19th person to be inducted into the 100×100 club. Half of her 100 finishes included mountain trail 100s

In 2019 she became aware that she had 85 100-mile race finishes and set an ambitious goal to soon reach 100 finishes. Her 100th finish came on February 3, 2021, at Grandmaster Ultras in Arizona, just three weeks before her 60th birthday. She became the 19th person to be inducted into the 100×100 club. Half of her 100 finishes included mountain trail 100s

She said, “When I compete in a 100-mile race, I do it one mile at a time. In my own mind, I’m not really running 100 miles. I’m running one mile 100 times, which to me, as weird as it may sound, is something very different.”

Since reaching the 100×100 milestone, Pam has finished an additional seven 100s as of 2022, including the difficult and cold Arrowhead Winter Ultra (135 miles), Hardrock Hundred, and Cocodona 250, all while over the age of 60.

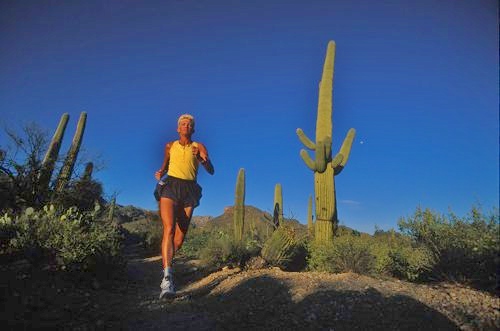

The Desert Ultra Legend

Of her more than 200 ultra finishes, at least 100 could be classified as Desert ultras. Pam Reed is truly the legend of desert ultramarathons. She said, “There is something inside my soul that when I’m in the desert, my body feels so much better. My muscles would be warm enough and I could just go on forever. It is also the beauty of it. I love all the cacti. When I went to Death Valley, it was like wow! It felt like I was at the bottom of an ocean. All of my crew was just as much into the desert as I was. You see the beauty in the oddness of it.”

Of her more than 200 ultra finishes, at least 100 could be classified as Desert ultras. Pam Reed is truly the legend of desert ultramarathons. She said, “There is something inside my soul that when I’m in the desert, my body feels so much better. My muscles would be warm enough and I could just go on forever. It is also the beauty of it. I love all the cacti. When I went to Death Valley, it was like wow! It felt like I was at the bottom of an ocean. All of my crew was just as much into the desert as I was. You see the beauty in the oddness of it.”

Pam loves the Grand Canyon too. “When I go to the Grand Canyon, I just get chills, it is so amazing to me, being able to run down and have all those changes.” She has also finished Zion 100 ten times which also gave her the beautiful desert canyon feeling.

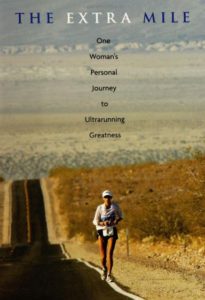

In 2005, Pam authored the book, The Extra Mile: One Woman’s Personal Journey to Ultra-Running Greatness. She still has a goal to write another book about aging runners.

In 2005, Pam authored the book, The Extra Mile: One Woman’s Personal Journey to Ultra-Running Greatness. She still has a goal to write another book about aging runners.

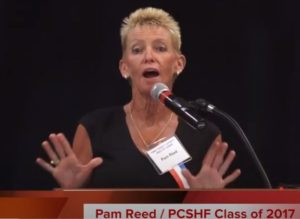

In 2017, Pam was inducted in the Pima County Sport (AZ) Hall of Fame. Pam’s original mentor, Bennie Linkhart was there and passed away within the year. In 2019, Pam was also inducted into the Arizona Runner’s Hall of Fame, sponsored by the Phoenix 10K.

In 2017, Pam was inducted in the Pima County Sport (AZ) Hall of Fame. Pam’s original mentor, Bennie Linkhart was there and passed away within the year. In 2019, Pam was also inducted into the Arizona Runner’s Hall of Fame, sponsored by the Phoenix 10K.

As of 2022, Pam has finished 64 full Ironmans including nine finishes of the Kona Ironman. “The Ironman is like a 100-mile run to me which of course it’s not, it is more like 100 km. But I get the same satisfaction from an Ironman.”

In 2022 Pam was competing in an Ironman in St. George, Utah when a spectator walked into her bike. She broke her femur and hip and was still recovering six months later. She once said, “I have to admit that running is like breathing for me. I don’t know what would happen if I couldn’t run.” With her current struggle to recover from injury, she added, “I’m struggling right now because running has always been so easy for me, but right now it’s not as easy as I want it to be.”

In 2022 Pam was competing in an Ironman in St. George, Utah when a spectator walked into her bike. She broke her femur and hip and was still recovering six months later. She once said, “I have to admit that running is like breathing for me. I don’t know what would happen if I couldn’t run.” With her current struggle to recover from injury, she added, “I’m struggling right now because running has always been so easy for me, but right now it’s not as easy as I want it to be.”

When asked about her future goals, she replied, “I still want to run across America. That has been a goal of mine for so long. I would like to do the Ultraman in Hawaii. Ultraman is like a double Ironman in three days. I want to do UTMB next year. Hopefully I’ll get back into Hardrock.” Congratulation to Pam Reed, the “desert ultrarunning legend,” a 2022 inductee into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.

When asked about her future goals, she replied, “I still want to run across America. That has been a goal of mine for so long. I would like to do the Ultraman in Hawaii. Ultraman is like a double Ironman in three days. I want to do UTMB next year. Hopefully I’ll get back into Hardrock.” Congratulation to Pam Reed, the “desert ultrarunning legend,” a 2022 inductee into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.