Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 34:06 — 41.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

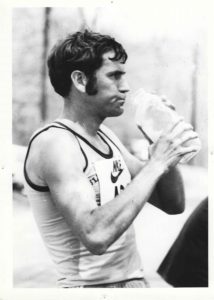

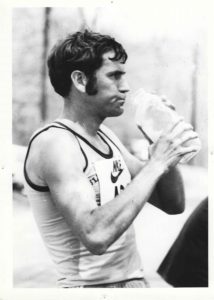

Barner won, and he won often. At one time he held the world record for the 24-hour run and other ultra-distance American records. But he said that he didn’t really need trophies or wins to feel satisfied. To him, running was something he enjoyed doing. He said, “It makes me feel good. I sort of feel like a kid.”

Of Barner, it was written, “He had a unique depth of constitutional strength and resiliency. The stories of his ‘outside the box’ exploits are nearly as impressive as those of his greatest races and have contributed to his almost mythical status in the history of the sport. He was called, “The Lonely Machine,” “The American Record,” “The Human Treadmill,” and “The Human Metronome” for his even-paced racing.

In 1974, one who knew him well wrote, “What Park has done is merely to shatter the existing standards of what the human body is physiologically capable of doing. He is establishing himself as a living legend in the ultra-distance events.” During the oil crisis of 1979, it was written about him, “Park Barner is the guy with the answer to gasoline prices.”

Today few runners have heard about Park Barner. Here is his story.

Early Years

Park Ivan Barner Jr. was born January 13, 1944. His father, Park Ivan Barner Sr. (1922-1992) was an electrical technician and in military service when Park was born, He soon went away to serve with the Army in World War II while Park was only an infant. Their Barner ancestors were farmers who lived in Pennsylvania for six generations and had immigrated from Switzerland in the mid-1700s. They settled in the beautiful farm area that is known as the Pennsylvania Dutch (German) region, near Harrisburg, along the Susquehanna River.

After returning to the United States in 1968, he was stationed at Fort Devens in Massachusetts. One evening after a ball game he decided to walk the 38 miles back to the base. He went through the night and finished at 10:00 a.m. in the morning. Soon after, he started running seriously at the age of 24.

Barner said, “nothing special got me going into running. It’s just wanting to run farther and farther all the time. Running just made me feel better.” In 1969 after spending four years in the army, as he was getting ready for civilian life, he was told by an Army doctor looking at his aching knees, “You’d better forget about running.” But Barner had been dreaming about running the Boston Marathon and after he got out of the Army, he started to seriously train. Three months later he finished Boston slowly, in 5:16. He said, “I think I was about 900th. I ran the first eight miles and limped the rest of it. I had tendonitis in my left knee.”

A year later he trained harder to do better at Boston. A month before the race in one weekend he ran 45 miles and 36 miles. At the 1970 Boston Marathon, he drastically improved, running it in 2:47:45 for 135th place.

At the 1971 Boston Marathon, he met ultrarunning legend Ted Corbitt (1919-2017) and asked him, “How do you run 100 miles?” Ted’s reply was, “You just have to tell yourself to keep going.” Barner finished Boston that year in 2:50. He quickly believed he had peaked at the marathon, and inspired by Corbitt, was ready to go further.

Barner at the age of 27, in 1971, started running ultra-distance races. He didn’t realize how far he could go until he ran from Harrisburg to Breezewood, Pennsylvania, a distance of 88 miles, to visit a friend. He said, “I finished just when the sun was setting, going down that last hill into Breezewood. I felt so great; it was exhilarating.”

Metropolitan 50

In the 1970s Barner ran the country’s preeminent 50-mile races regularly. One of these races was the Metropolitan 50, held in Central Park in New York City. The race began in 1971 and attracted many elite runners who later progressed to the 100-mile distance. The course for the race was run on asphalt with four-mile loops and a one-mile out and back. The race was held on weekends when car traffic was not allowed in the park. It was often the road 50-mile National Championship and other years was pretty much the unofficial championship because it was so competitive.

One runner described races in Central Park: “That park is crowded, not with race participants, but with people on training runs, joggers, walkers, bikers, skateboards, or roller skates. Dealing with these hordes during the late stages of a race presented an interesting problem.” Another commented, “The crowds of joggers and the constant short hills and turns on the course keep the runner alert. There was also the contrast between natural scenery and dramatic city walls, the sense of being in the center of a great city.”

At the 1972 Metropolitan 50 Barner went into the lead at mile 36 and continued on to claim the win in 6:04:01, the first 50-mile race he ever ran. He wept with joy. It was the first time he had ever led and won a race. He ran that race nearly every year. His times improved to 5:50 and he finished it ten times.

JFK 50

When Barner first ran the JFK 50 in 1972, he competed with an astonishing 1,075 hikers and runners. He had visions of beating the course record of 6:15:42 set the previous year by Elton Horst, a talented cross-country runner at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virgina.

London to Brighton

England deserves much of the credit in the 1950s for reestablishing ultras in the modern era, and specifically the 50-miler. The London to Brighton 52-miler began as an official running race in 1951. Ted Corbitt of New York City established post-war ultra-distance races again in America as a means to qualify to run London to Brighton. Ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy, wrote, “The London to Brighton race was to be a major catalyst in the development of the North American ultrarunning.”

Barner quickly knew that he needed to make the pilgrimage to run London to Brighton. He ran the famed race in October 1972 and finished 12th in 5:56:58, the only American finisher that year. Later in Runner’s World Magazine it was written that he had run London to Brighton after a 24-hour fast of no food. “Not only did he finish without having his energy dry, he ran almost a half hour faster than his previous best for 50 miles.”

Lake Waramaug

Barner ran Lake Waramaug in its inaugural year, 1974. This was Barner’s first 100 km race. He won, beating Ted Corbitt (age 54 at that time), with a time of 7:37:42, setting an American Record for 100 km. Along the way he also won the 50-miler in a blazing time of 5:55:30. He would win the 100 km there for the next two years and finish Lake Waramaug 100 km nine consecutive years.

Once while running there, Dave Obelkevich recalled that Barner stopped to get some food from his wife. Obelkevich and Leslie Watson (from England) pass him. When Barner resumed running and caught up to them, he went by without a word. Obelvevich yelled out, “Hey Park, this is Leslie Watson from England, trying to break the world record for 50 miles. ” Barner turned and said, “Oh.. Good luck.” Yes, Barner was a man of few words.

Ultrarunning fame grows

By 1974, Barner was no longer a new-comer in American ultrarunning. He was becoming the best ultrarunner in America. In April 1974, Barner appeared on a local television show. The episode was entitled, “The Loneliness of the Ultra-Distance Runner.” The Harrisburg Area Road Runners Club Newsletter wrote, “What Park has done is merely to shatter the existing standards of what the human body is physiologically capable of doing. He is establishing himself as a living legend in the ultra-distance events.”

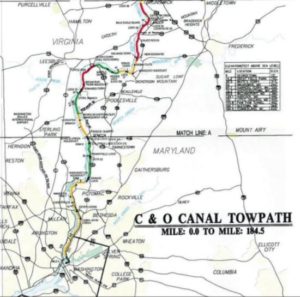

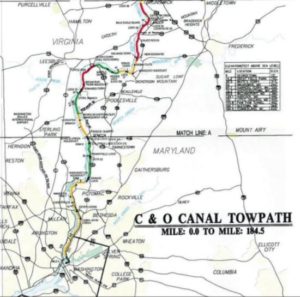

1974 C&O Canal Race

Barner had his eye on a new very long “supermarathon” of 300 kilometers (186 miles). Late in 1974 he put in 1,266 miles during two months to prepare, including a 194-mile week. Two weeks prior, he placed second at the Metropolitan 50.

The race was in November 1974. He went to Washington DC to run the length of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O Canal) dirt towpath from Georgetown to the canal’s end at Cumberland, Maryland, a distance of 300 km or about 186 miles. The race was put on by Robert Crane of Vienna, Virginia. Runners ran this race in three days, 100 km each day. No one had ever run the Canal in three days. The 300 km course began at the Washington Monument and wound its way about a mile to where the C&O Canal towpath began in Georgetown, Maryland.

Barner covered the 100 km segments with amazing consistency and speed, 7:52, 8:12, and 7:48. He averaged 7:42-mile pace spread over the three days for a total time of 23:53:54. Six other runners entered and only one other finished, Alan Price, with a time of 46:46:00, nearly double Burner’s time.

1976 C&O Canal Race

He reached the 100-mile mark at 16:14:10. He then ate, slept in his crew’s car for a half hour, and felt better. He said, “Once I got in the car, they had the heater running and I napped for about a half hour. But when I warmed up, I started shivering. Once I started running again, I felt like I was just starting out fresh.”

After that break he was able to average nine-minute miles. Later on, his crew couldn’t find him for a while. Somehow, he was missed at a planned checkpoint. Four hours later he became dehydrated and had resorted to walking. At mile 156 he decided to wait if no one was there, but luckily his crew showed up and took care of him during a 35 minute break. He drank his favorite drink of orange juice mixed with honey.

Barner finished in 36:48:34. None of the other five entrants finished. The next day he ran a recovery run of eight miles at 8-minute-mile pace. Three days later he ran at 6:15 pace feeling the best he had felt in two years. (For those who care about the C&O towpath fastest known time, it should be noted that Barner’s time included about two extra miles off of the towpath to bring the race mileage close to 300K. It was estimated that his time on the towpath end-to-end was about 36:30 which is faster than the published time of 36:36, accomplished by Michael Wardian in 2018.)

Back-to-back Barner

Barner was famous for his “back-to-back” runs. For example, in 1973 he finished a 50 km race in Vermont and the very next day finished 3rd at the inaugural Harrisburg Marathon.

In 1974, just two weeks after his first C&O run, he ran a marathon personal best of 2:37:28 at the Baltimore Marathon on a Saturday and followed that up with a 2:39:26 the very next day at Philadelphia. At that time, it was thought to be the fastest American marathon double.

In 1976 he ran a 50-miler in New York on a Saturday in 5:54:22 and the next day finished the Harrisburg Marathon in 2:51:08.

In 1977, he set a course record of 6:13:22 in the Stone Mountain 50-miler, in Georgia. The race committee paid for his motel, a first for Barner. After finishing, he then boarded a bus and rode 19 hours to arrive five minutes before the 7 a.m. start of Maryland’s Beltsville marathon. The bus seat was so cramped that the 6’1½”, 162-pound Barner could not even bend over to change into fresh socks. He ran in them again and finished in 3:01:22.

Later it was written about Barner, “Normal men—those, say, with one heart, two legs, two arms and the requisite amount of marbles—do not attempt ultradistance races or even marathons two days in a row, certainly not four on consecutive weekends. But Barner, who is so unassuming that he makes Don Knotts seem like Don Rickles, has run 14 ‘back-to-backs,’ as he calls them, nine of them combinations of marathons and runs of 50 miles or more, and he says, ‘I usually feel better the second day.’”

100-miler

Barner tried to break Corbitt’s record the next year at the same event and was leading at mile 67 when he injured his hip. The temperature was in the 90s so he decided to drop out.

1976

In March 1976, Barner won yet another 100 km race at Mechanicsburg Navy Depot, in Pennsylvania, with 7:11:44, lowering his own American record. The course was on a six-mile loop during “inhospitable conditions of frequent wet snow squalls through the day.” During that race, he hit the marathon mark at 2:58 but was seven minutes behind the leader. He caught up at mile 46 and went on to win. (Frank Bozanich would best the record in 1979, in Miami, with a 6:15:21).

Barner completed another astonishing double later that year. On October 2, 1976, he ran a 2:48:38 marathon at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. After finishing he jumped in his car to drive to run the New England AAU 50 Mile Championship on the very next day in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He had to drive ten hours, stopping for only five hours of sleep, and arrived right before the start.

He said, “The race hadn’t started and I was picked as the favorite to win. They made it sound like all I had to do was finish. About a dozen of us started out in a drizzle and for almost 20 miles, 7:20 pace, I didn’t feel bad although my legs ached the whole time.” He then slowed down and was passed by New England ultrarunning legend, Roger Welch, who went on to win. Barner finished second in 6:37:43. Barner had the ability to recover very fast from a race and showed up at nearly all of the races in the Northeast United States.

1977

While other runners were meticulous about their diet, Barner gave little thought to diet and ate whatever he wanted. The day before a 24-hour run, Barner ate 1½ pounds of oatmeal cookies. “Driving from a New York City 50-miler to the Harrisburg marathon he stopped at a McDonald’s, where he had two large orders of French fries, three milk shakes and a piece of apple pie. He says he rarely eats steak or chicken, and his normal lunch on a workday consists of a bag of peanuts, popcorn or corn chips. He also takes wheat-germ oil and multivitamins with minerals”.

Barner would race with a relentless “metronome” pace, rather than using blazing speed at the beginning of a race. Frequently he would run the second half of a race faster than the first half, producing rare negative ultra splits. He had the reputation of being very durable, only wearing a T-shirt and shorts when running in sub-freezing weather. Once when he ran JFK 50, the race was hit by freezing rain. An amazing 1,100 runners didn’t finish, but Barner finished in second.

By 1978 Barner had finished 41 races of 50 miles or longer and won 19 of them. At that time, legendary Ted Corbitt, had finished at least 16 ultras, so Barner’s 41 finishes was incredible for the time when few ultras were held. Ultrarunning pioneer, Tom Osler, said, “Park is a very unusual creature.”

Unisphere 100

Barner maintained a 9-minute lead at mile 68, but at that point the second place runner chasing him crumbled. Barner reached mile 75 in 9:55 and cruised to the win, with a time of 13:57:36, which was thought at that time to be the second fastest road 100 time ever for 100 miles. His only complaint was that the course was too flat. “I would have preferred a few hills.”

When asked about what Barner thought about while he ran that far, he replied that he simply lets his thoughts wander, daydreaming as if he is a motorist. “It’s the same thing as when you’re driving a car hour after hour on a turnpike.”

24-hour American Record

At the Glassboro, New Jersey 24-hour race, there were nine starters who ran on a cinder track at the State College. Don Choi, the American record holder pushed a fast pace and built up a 18-lap lead on Barner. By mile 100 at 15:04, Barner was just eight minutes behind. Choi started to falter and quit at 113 miles. Choi said of Barner, “People always ask me, ‘Is he human?’”

Barner ran in a T-shirt and shorts the entire time while the other runners were bundled up. During the race he drank three quarts of Gatorade, two quarts of diluted orange juice, one quart of coffee, and 1 ½ gallons of water. Before Power Bars existed, Barner would eat frozen chocolate cookie dough during his ultras.

At mile 103 Barner stopped briefly to change shoes because he could feel the cinders through the thin-soled shoes he was using. He still was running strongly and finished with 152 miles, a new American record, breaking Choi’s previous record of 136 miles. The World Record at that time was held by Ron Bentley of England who ran 161 miles. Barner would next set his sights on that record.

After the race he commented that he could have run 300 miles and wondered when someone would hold a 48-hour race. Hungry for more races, after only a two-hour nap, he drove to Maryland to run a 50-miler the next day where he finished 5th in 8:16:21. Ed Dodd recalled, “I was lying in a van after the race, getting ready to puke, when I saw Park put his stuff in a small Volkswagen bug and drive off for his 50-mile race the next day.” A week later Barner ran Metropolitan 50 in 6:37:30 and the following day ran a marathon in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 3:26:41.

Park Barner – America’s Ultrarunner

About his training, “Barner dismisses the concept of special training and said he simply runs to and from work and during his lunch break. Sometimes on Monday night, he throws in a 20 or 25-mile workout.” He didn’t drive a car. He said he liked to make running natural. “I don’t do any speed training or any of that junk.”

A member of Barner’s Harrisburg Road Runners Club said, when told that sometimes in winter Park doesn’t use the Taylor Bridge across the Susquehanna River, but runs across the river ice, “That’s nothing. He’s been walking on water for years.”

1979

Barner was human. In January 1979, he was favored to win the RRC’s American National Championship 100 km in Miami on a 3.3-mile loop with 83 runners. The heat bothered him terribly. He finished 12th, in 9:12:38, and Frank Bozanich, smashed Barner’s 100 km American record by winning with a 6:51:20. (Don Richie of Scotland held the world record of 6:10.) Barner said of Bozanich, “This clearly puts him at world-class level.”

In April 1979, Barner spoke on “ultramarathoning” at The International Jogging/Running Expo at Boston, before the Boston Marathon. Also that month a feature article appeared in a local newspaper about Barner as he was helping with a Bike/Hike for the mentally disabled. “Barner does things that defy belief. This guy, you say to yourself as you gee-whiz at his accomplishments, certainly can’t be playing with a full deck. Barner is what is known as an ultra-marathoner.” Barner admitted, “I don’t know of many people who’ve run in as many ultramarathons as I have.”

24-hour World Record

For the 649 laps, Barner lost eight pounds and drank 17 quarts of liquid that weighed about 42 pounds. He said, “I didn’t stop and only had one bathroom stop, and that was it.”

About the record, he said, “It was something that just happened. After I ran 100 miles, I felt the best I had the whole run. I knew I had a shot at the record.” Barner received an invitation to appear on The Tonight Show, hosted by Johnny Carson. He turned it down because he preferred to save his vacation days for traveling to ultras. He did later appear on the network show, “PM Magazine.”

Later, the world record wasn’t accepted by those in the U.S. trying to control running records at the time, because the race did not record lap times as was currently required even though the protocol had be given ahead of time to the race director. The lap recorders checked off each lap, and only recorded the time for each mile with a clock time, hour and minutes, without seconds. Barner said he wasn’t disappointed because of the technicality. But honest history does include this record, one of Barner’s greatest accomplishments. He never again would try to break his 162-mile record. He said, “If I ever tried to, it wouldn’t work out. I just like to run. I don’t like to put pressure on myself. Running is its own reward.”

More 1979 Accomplishments

Just a week later in 1979, Barner ran in a historic 100-mile race at Flushing Meadows in Queens, NY. At this race, the famed runner from Scotland, Don Ritchie, set a road 100-mile record of 11:51 on the 2.27-mile loop course. Barner came in third with 14:14. It was a remarkable achievement with only six days rest since his 24-hour world record. Four runners broke 15 hours. Barner had won seven out of his last ten 100+ milers. But during this race, he suffered a rare running injury for him. He had pulled a muscle in his left knee at the 40-mile mark and favored the knee for the rest of the way. He took eight days off to heal and then started running again. In 1981 he ran the Queens 100-miler again and finished 3rd with 14:11.

In September 1979, Stan Cottrell of Georgia, a fitness consultant, claimed that he broke Barner’s 24-hour world record by running solo 167 miles on a high school track. Cottrell’s claim was not part of a race, lacked independent witnesses, and was never verified. He was later exposed as a fraud. Sadly, Cottrell’s story went nationwide and took away from Barner’s true accomplishment.

1980

In January 1980 Barner ran 689 miles. He explained, “I don’t like to think of running as training, so I try to accomplish something when I run. Last month I had jury duty in Carlisle, so I ran the 31 miles there every day. A couple of times, I ran home and took the long way which is 51 miles. A couple of Saturdays ago I wanted to go to Hershey, Pennsylvania to buy a stopwatch. I decided to run there and back, and I got in 40 miles.”

Barner ran 100 miles in 16 ½ hours at the Dallas Aerobic Center after only 11 hours of sleep the previous two nights. He called that performance “a bad day.”

Miami 48-hour Run

I

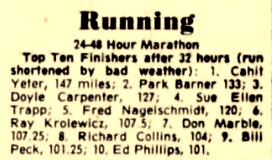

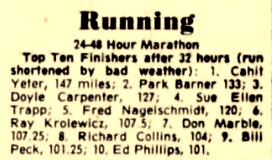

Barner reached 51 miles in a relatively slow. 7:47:45. He said, “I’m not sure exactly what it was. It may have been that I did too much speed training. I know I never trained harder for a race. He covered 115 miles on the first day. But on day two, a terrible thunderstorm dumped heavy rain on the track and the area was under a tornado warning. When Barner could hardly walk, he quit after 27:46 with 133 miles. The race was stopped at 32 hours, 25 minutes. All runners were ordered off the track and two hours later the race was cancelled for “runner safety,” spoiling one of the earliest 48-hour races in modern US history. Sue Ellen Trapp did set the 24-hour world record with 123 miles.

Barner did significantly back off his racing in 1980. He insisted that he was just a guy who enjoyed running. “I still don’t feel like I’m number one. I feel the same way I did when I started running seriously in 1968. I try not to let anything affect me. I don’t need trophies or wins or anything. It’s something I enjoy doing. It makes me feel good. I sort of feel like a kid.”

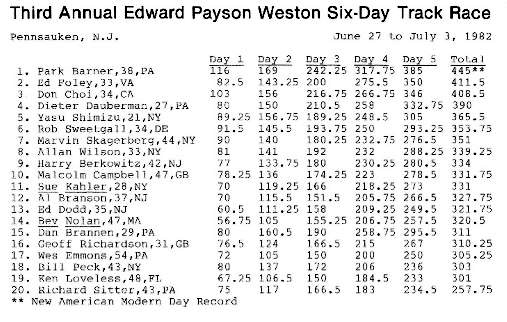

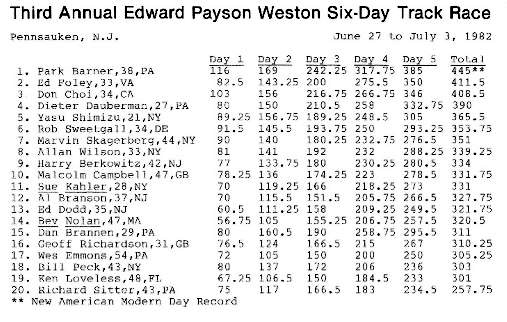

Weston 6-day Race

In 1980 the six-day race returned to America after being away since the very early 1900s. Ed Dodd, a math teacher from Collingswood, New Jersey, had been researching the early Pedestrian races of years gone by and became acquainted with Don Choi, a postman from San Francisco who put on a 24-hour race and the first modern-day 48-hour races in Woodside, California, in 1979. Dodd went out to run in those races and stayed with Choi where they talked about six-day races. On July 4, 1980 Choi hosted the first modern-day six-day race since one held in 1903, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Choi’s race was held on a track at Woodside, California and he won with 401 miles.

Two months later, also in 1980, Dodd organized his own race, the “Edward Payson Weston Six-Day Go-As-You-Please Invitational Track Race” held at Cooper River Park’s cinder track in Pennsauken, New Jersey.

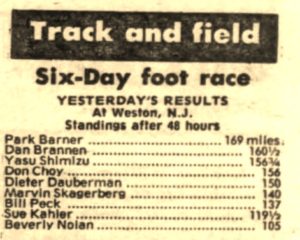

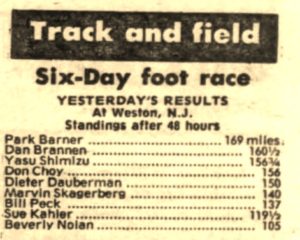

Barner took the lead from Choi at mile 81 and posted the highest mileage that day, with 128 miles. Defending champ Choi developed stomach trouble and badly blistered feet. He was essentially out after 106 miles and hobbled onto the track to shake Barner’s hand already conceding the competition to him. Choi said, “I did everything wrong. I changed my diet and wore different shoes.”

About the runners, it was reported, “Almost everyone used something light-weight and as wide as possible on their heads, short of a sombrero, at some point to keep the sun off. There were thick sponges soaking in a tub of water for the taking and cold drinks on a table, although many runners provided their own particular fluids.”

After the first day, Barner’s strategy involved never being on the track for more than 12 hours per day, and then to rest at motel nearby. At one point he was off the track for 15 hours straight. “But while on the track he was a machine.”

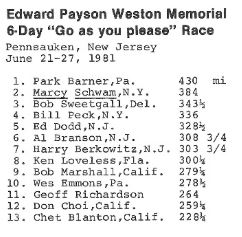

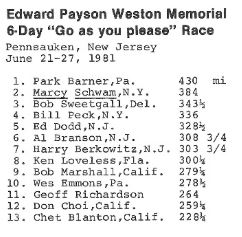

Barner reached 262 miles after three days. A thunderstorm flooded the track on the fourth day and he led with 316 miles. After he broke Choi’s previous year’s 425-mile record, and adding five more for 430 miles, he decided to not run the last few hours. He had a comfortable lead and watched from the stands. He said, “I felt no need to be with those people still running, I’m not a racer. I just run. It’s a natural thing to do.”

In the end he won with 430 miles. Marcy Schwam also won with 384 miles and placed second overall. Barner was asked how many shoes he went through. He replied, “Joggers bounce, and wear out their shoes. Runners glide. I get about 4,000 miles from a pair.”

Barner’s wife, Gail (1951-2013), also a computer programmer, came along for these six-day races to crew him. She packed books, puzzles and set up a lounge chair and quilt, to cheer him on. In return, she received a two-day vacation on the New Jersey beaches. She said, “My idea of a fun vacation is walking along the boardwalk, eating fattening food and relaxing.”

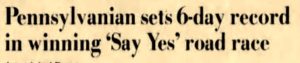

His racing strategy produced 445 miles over the six days and broke the modern-day American record. Barner said, “Apart from running, resting is what I do best.” With his win, he kept possession of the Weston Cup, which he kept on top of his television set.

Barner ran again in the 1983 Weston race, admitted that he was out of shape, and but finished down in the standings with “only” 303 miles. Choi won with 460 miles for a new record.

Barner was indeed an ultrarunning legend. One runner at Weston commented, “I got to run with him and I enjoyed talking to him. He’s the first ultra-marathoner I ever heard about so I was glad to meet him.” Barner ran again in 1984 but only completed 277 miles, finishing in 24th place.

Long Journey Races

Retirement from Ultrarunning

But Barner participated in other activities as an outlet for his intense drive to excel. In 1983 at the age of 39, Barner bowled 39 games and averaged a score of 199. He also had the ability to pitch a softball fastball at 60-65 mph.

Once he retired from running ultras by the 1990s his mileage dramatically dropped to as low as 10 miles per week. He did continue running some marathons.

Barner thought back on the psychology of ultrarunning and said it was more about “trying to keep yourself under control.” When asked about his most memorable ultras, he recalled fondly his experiences running 100 km at Lake Waramaug in Connecticut.

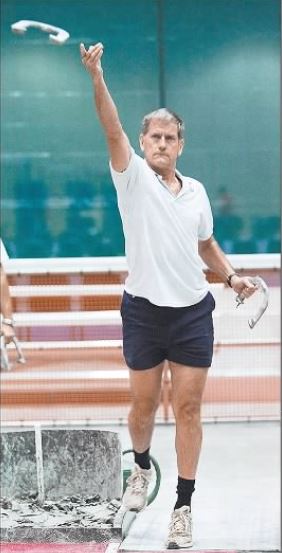

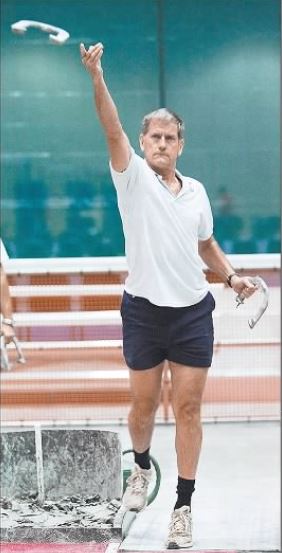

Barner competed at the National Senior Games – in horseshoes. One reporter observed, “Barner looks younger and fitter than most of his competition. And the look in his eye suggests he is totally focused. Ask him if he has tried other sports and he replies without fanfare, ‘I was once one of the best ultramarathoners in the world.’”

Barner reflected, “I try to be humble, but the older I get, the more I think about these things and what I did. I look at my logs and I think, ‘Did I really do that?” Yes, he did. In his hey-day he ran 50 miles in under 6 hours 19 times with his best of 5:42:07 in 1981. He ran at least 100 miles in about 13 races during his career, with his personal best 100-mile time of 13:40:59

Barner still ran about two marathons per year but said that pitching horseshoes took up too much of his time. “One day a year, I go out and try to make a thousand ringers.” It would usually take him eight hours. “I break a lot of horseshoes. It takes about 10,000 pitches to break a shoe for me. I’ve broken over a hundred since I started pitching and these babies aren’t cheap, about $50 a pair.”

In 2012 Barner was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. In 2016, at the age of 71, he was still running in the Harrisburg Marathon. He finished in 6:56 for his 44th finish there. In 2019, Barner finished there for the 47th time. He walked nearly the entire way and was more than five hours slower than his first run there in 1973. “He graciously allowed all 653 other participants to cross the line ahead of him.”

In 2020 Park Barner was 76 and living in Mill Hall, Pennsylvania.

Sources:

- Jim Shapiro, Ultramarathon

- https://vault.si.com/vault/1978/11/20/on-and-on-and-on-and-on

- The Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), Apr 18, 1972, Apr 26, 1975, Aug 8, 1980

- Public Opinion (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), Feb 2, 1973, Sep 15, 1978, Apr 21, Jun 11, 1979

- The Sydney Morning Herald (Australia), Mar 14, 1976

- The Baltimore Sun (Maryland), Mar 1976

- The Potter Enterprise (Cloudersport, Pennsylvania), Jun 16, 1876

- The Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland), Nov 22, 1976

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Jun 25, 1978

- The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), Jul 1, 1978, Oct 13, Dec 8, 1978, Feb 29, Mar 1,3, 1980

- Calgary Herald (Canada), Aug 26, 1978

- The Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), Oct 24, 1978

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Oct 29, 1978, Jun 18, 1984

- The Ottawa Journal (Canada), Jun 18, 1979

- The Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey), Jun 29, 1979, Jul 5, 1981

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Dec 2, 1979

- The Miami News (Florida), Feb 28, 1980

- The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey), Jun 8, 1981

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jun 17, 24 1981

- Courier Post (Camden, New Jersey), Jun 26, 1981, Jun 20, 26 1983

- The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), Jun 28, 1981

- Philadelphia Daily News (Pennsylvania), Jun 29, 1981

- Detroit Free Press (Michigan), Sep 25, 1982

- The Daily Journal (Vineyard, New Jersey), Jul 5, 1983

- Ultrarunning Magazine, September 1981, September 1982, November 1982, September 1983, November 1998

- The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), Jul 6, 2007

- Nick Marshall, “Harrisburg Marathon History, 1973-2019”

- Harrisburg Area Road Runers Club Newslater #20 – November 7, 1976

- Nick Marshall, 1983 Ultradistance Summary

- Nick Marshall memories

- Ed Dodd memories