Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:12 — 34.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

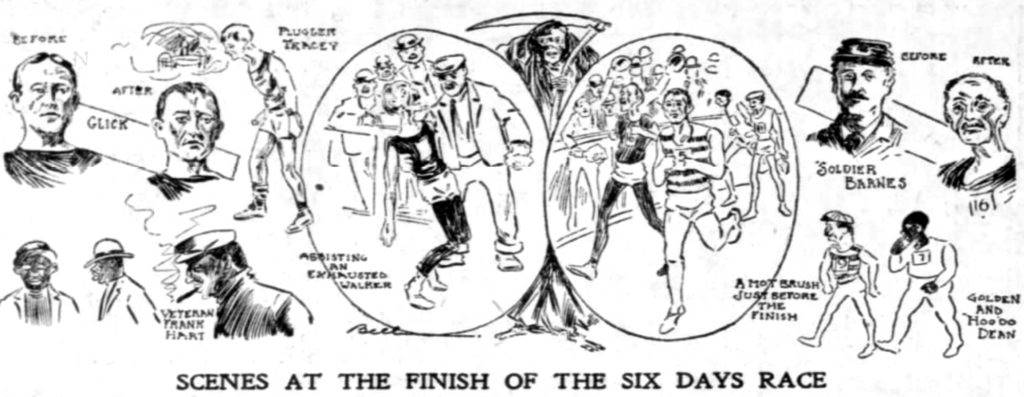

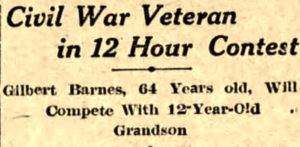

Old Soldier Barnes was a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who became a very popular professional ultrarunner in 1900 when he was in his early 50s. He must have not worn his age well, because people always thought he was much older than he really was. He entered the sport when the six-day race was making a comeback in Pennsylvania, about 20 years since its heyday in the 1800s when it was a huge spectator sport, watching walkers and runners go in circles for six days trying to travel as many miles as possible.

Old Soldier Barnes was a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who became a very popular professional ultrarunner in 1900 when he was in his early 50s. He must have not worn his age well, because people always thought he was much older than he really was. He entered the sport when the six-day race was making a comeback in Pennsylvania, about 20 years since its heyday in the 1800s when it was a huge spectator sport, watching walkers and runners go in circles for six days trying to travel as many miles as possible.

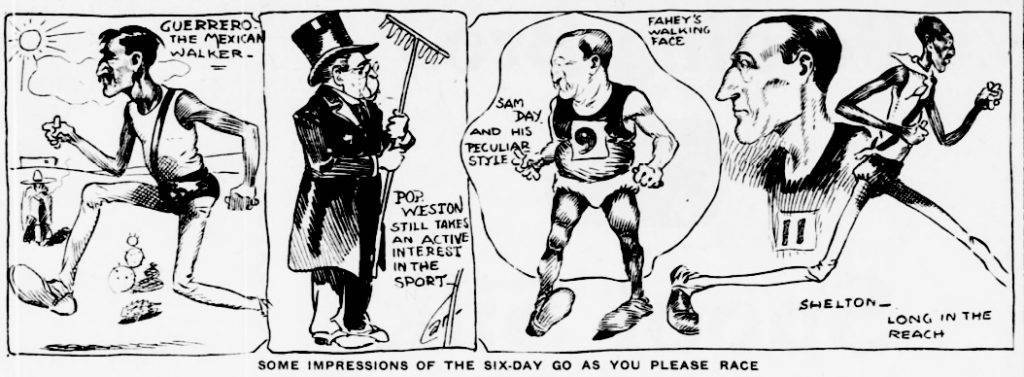

There was a brief resurgence of six-day “go as you please” races in America from 1898-1903 until states passed laws to halt these all-day and all-night running affairs along with similar six-day bicycle races.

Soldier Barnes, in his 50s, became a highly competitive tough multi-day runner who was well-respected and always a crowd favorite. He was one of the most prolific six-day runners of that time. This article will follow his participation in the sport and hopefully leave readers with a deep understanding of the fascinating six-day running races that were held about 120 years ago.

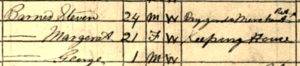

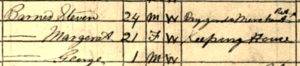

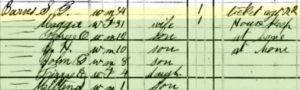

Stephen Gilbert Barnes was born on May 23, 1846, in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania. He lived in that area near Pittsburgh his entire life and went by “Gilbert” during his running years. Gilbert Barnes’ ancestors were nonconformists of England, some who suffered martyrdom in England. His ancestor, Richard Barnes settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony before 1636. His grandfather and namesake, Captain Stephen Barnes (1736-1800) commanded a company during the Revolutionary war and settled in Pennsylvania. His parents were Pennsylvania natives. His father, Joseph Barnes (1777-1855), was a millwright and built ferry boats, and his mother Clara Elizabeth Leer (1818-1847), died about a year after he was born.

Early Life

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Barnes enlisted in the Pennsylvania Reserves. At the end of his enlistment, he tried to reenlist but they were not recruiting at the time. He then joined Company K of the Pennsylvania Cavalry and fought with them throughout the rest of the war.

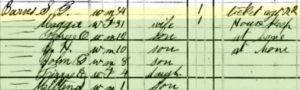

After the war, in 1868, Barnes married Margaret Elizabeth Couch (1848-1915) and they had six children from 1869 to 1884. By 1874, he was a dry goods merchant in Springdale, Pennsylvania, but had huge debts of about $7,000 and filed for bankruptcy. It was granted and some of his property was put up for sale and liens liquidated within two years.

By 1880 he lost his store and was a ticket agent for the railroad. On Mar 26, 1880, he became postmaster for the town of Armstrong, Pennsylvania. In 1884 a newspaper was started in Indiana, Pennsylvania called the “Indiana Weekly News.” Barnes was employed as the editor for many years.

Barnes was always proud of his military service and was a member of the G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) in Post 157. The G.A.R was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army, Union Navy, and Marines who served in the Civil War.

By 1898 Barnes became a professional runner and he worked very hard to be able to finish high enough to win monetary awards. Fixed-time multi-day races, especially the six-day race had become well-established in the 1870s. Those who competed in them were call pedestrians. These races at first observed strict “heel-toe” walking rules but eventually progressed into “go-as-you-please” formats open to both walkers and runners. Barnes became a runner.

1898 Pittsburgh 72-hour six-day race

In February 1898, it was announced that the six-day race “go as your please” footrace would be revived in Pennsylvania after a long absence. A 142-hour race was planned to be held in Saenger Hall, the largest “amusement building” in the city. Unfortunately, plans were changed to hold a six-day bicycle race instead, building on a recent successful event held in Madison Square Garden, in New York City. Nevertheless, the seed was planted, and Barnes likely followed the news of multi-day foot races returning.

The newspaper reported, “The professional pedestrians entered the ring at noon and got away promptly upon the sounding of the gong. The men started off with a vim and spirit that augurs well for a very exciting race. The old soldier Barnes was loudly applauded. The pace was so hot that he had to remove his uniform before many laps were covered. The uniform, however, served to arouse the spectators to a high pitch of patriotic fervor and there were many cheers for the gallant soldier. The old man was walking a good pace and would keep the younger element keyed up to their best speed.” The nickname of “old soldier” would stick.

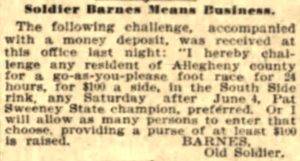

Running challenges for wagers

Barnes continued to issue challenges in newspapers to race at various distances, but willing contestants didn’t materialize or just didn’t show up for the races. At one event he ran a five-mile exhibition, and it was reported that he ran the five miles in 25 minutes! He also sought to race a horse.

1899 races in New York City

Barnes continued to learn and progress. On February 11, 1899 he ran in a 12-hour race at Grand Central Palace, a six-story exhibition hall, in New York City, with a field of 35 runners on a small track, 13 laps per mile. “Gilbert Barnes, the old G.A.R. veteran from Pittsburgh, looked sadly out of place among the young ones, but he held to the race bravely.”

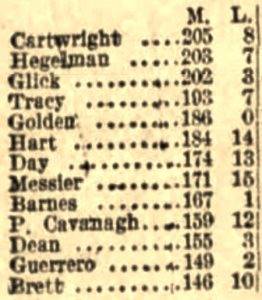

In May, he again competed in the Palace, this time in a 72-hour, six-day race, Barnes took with him Lon Taylor to “take care of his cooking department.” Cots and hotel accommodations were provided for the contestants so they would not need to leave the building until the race was over. After the first day Barnes had covered 60 miles, the leader was at 75 miles. Only a few spectators attended. Barnes reached 118 miles in the first 24 hours, 168 by 48 hours. A Swedish runner collapsed after reaching 200 miles, became delirious, and was rushed to the hospital. Barnes finished with 352 miles in the total 72 hours for 7th place. The winner reached 407 miles.

1899 International Six-Day at Madison Square Garden

On June 11, 1899, a unique race was held at Madison Square Garden, in New York City. This was the first the multi-day race to be held under a new state law that prohibited races for being held for more than 12 hours in a given day. They set up this race to be a 72-hour, six-day race with two waves, one starting at noon, the other starting at midnight with a total of 31 runners.

It was announced, “Everything is in readiness for the beginning of the race, the sawdust track being made and laid in accordance with the wishes of the pedestrians, which always have to be respected in this matter. Much depends upon the formation of the track and its construction, whether the contestants are able to stand the strain of a long, weary jaunt.”

From the start, it could be seen that New York spectators just weren’t responding to the return of indoors ultrarunning. At the start there were only 200 spectators. Barnes started in the second wave. As he was finishing up his first 12 hours, the manager of Madison Square Garden came for the daily rent and the runners noticed that something was wrong. After raising only $143 in gate receipts, the race manager, A.R. Samuels could not be found anywhere. He had been seen leaving at 10:30 p.m. and didn’t return.

But as the crowd started to dwindle away, the Garden management turned out the lights and drove away the rest of the runners at midnight. Barnes had the lead with 67 miles. At the end, everyone flocked around the scoring board. One of the runner’s trainers jumped up on the scorer’s platform and explained that his 61-year-old runner was left without a cent and was now stranded in New York. The hat was passed around and quite a contribution was collected. Many of the runners were furious with Samuels and wanted to go find him.

Some in the press were delighted with the race failure. “As for those ghastly shows known as ‘six-day races,’ one can only be thankful that they will soon run their course. However strong a man may be, there is neither rhyme nor reason in taxing his powers to this extent. But while the worship of brawn continues at its present level, there is small chance of such Idiotic exhibitions being entirely abandoned.”

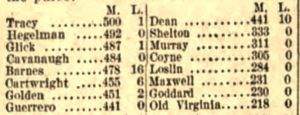

1900 St. Louis Six-Day

1901 Six-day Race in Philadelphia

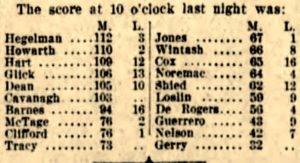

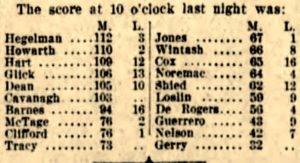

The pace was fast at the start, but after 21 hours, it was slow. “A fast walk is about the best show of speed that can be generated by the human walking machines. The challengers are greeted with cheers by the crowd. Gilbert Barnes’ pale face and bent shoulders carrying the weight of sixty-odd years (actually 55) is a man who attracts attention. He is an old soldier and started out bedecked with badges. These he has laid aside, as well as his army coat, and is down to solid business.” He reached 100 miles is less than 24 hours.

As the event progressed it was reported, “That the race will prove a big success is hardly doubted now, as all day yesterday and last night the big hall was crowded, and the police had their hands full keeping the aisles clear. At 10 o’clock there were over three thousand people in the place and their presence seemed to inspire new life into the already weary walkers, and the cheers and encouraging words of the spectators and the music of the band kept more than one from giving up in despair.”

On the second day, it was said that Barnes appeared to look the worst off. “One or two of the men have shown signs of going ‘daffy’ for a time. The first was Barnes who is being handled by his son. He looked at the track so continuously during the first two days that he imagined it was jumping up in his face and he began to walk backwards. He was given a rest and told to keep his eyes off the track. Since then he has been going around all right.”

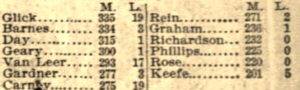

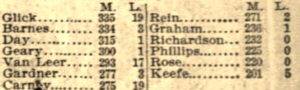

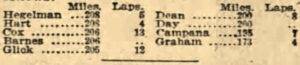

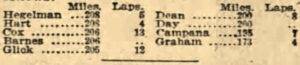

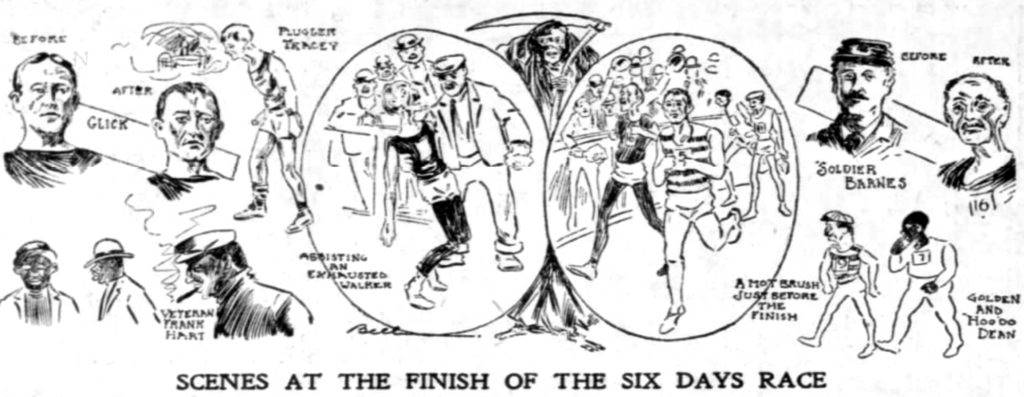

By Day 4, Barnes was in third place with 341 miles. On Day 5, he had reached 420 miles and was in second place, five miles behind the lead. “Gilbert Barnes is pushing John Glick hard and is calling up all the energy in his body to enable him to overtake the lead of Glick. Regarding the grand old man, the physician reported that his general condition was good. Barnes is the strong favorite. The old war horse keeps plugging along. He marches with the same air of hope and determination that made the Union arms successful against their countrymen. With a haircut and shave, he appeared on the track early yesterday morning. But at times he forgets the war is over and starts off at the double quick, yelling like he used to yell in the 1860’s, ‘Yip, Yip.’ Then he dashed off lap after lap in fast time.”

On the last day, Glick extended his lead and finish positions in the money were well established causing the runners to lose motivation for pushing hard. Those out of the money were begging the crowd to empty their purses for them. Barnes, ten miles back seem indifferent and the leader Glick was on and off the track. “The management, however tried to whoop things up, but its effort was in vain. There was nothing brutal about the finish. It was a calm and peaceful ending.”

Barnes placed second with 479 miles, and Glick won with 485. Because the crowds were large, Barnes’ share of the winnings was $900 (about $27,000 value in 2019 dollars).

After the finish the crowd cheered the runners.“When Gilbert Barnes put on this old army cap and carried a flag over either shoulder, the band struck up ‘Marching Through Georgia.’ The crowd went wild with delight.” He passed his hat around and gave his collection to a runner who was pulled off the track by the doctors. Then the men were introduced to the crowd and paraded around the track, headed by the band.

October 1901 Six-day in Philadelphia

The first day pace was fast, with few runners leaving the track for the first 12 hours. A few were singled out as pacemakers, and would be mirrored as they walked, ran, and rested. 1,000 people watched the first afternoon. Compared to the six-day race in the same venue earlier in the year, the live music was said to be greatly improved, with the rendition of popular airs which kept the men in good spirits. It was said, “Old man Barnes was not doing so well as last year and shows signs of weakening, but his trainers declared that he is on the improve and would show his old vigor by the night.” He reached about 90 miles on the first day.

Two runners started to get “cranky.” One complained that the scorer’s clock had stopped twice. Another had two or three fights with the scorers, claiming that they were taking off the count of his laps instead of adding to them. “One of the leaders suddenly stopped, and climbed over the rail and ran into the tent of one of the other contestants. He was missed by his trainers who eventually found him and dragged him out, and in a few minutes was back on the track going around as steadily as ever.”

Barnes reached 400 miles by the end of the fifth day, The field of 40 had dwindled down to only sixteen runners. “Nearly all day these weary-limbed contestants toddled around the track, unmindful of the pain they must have endured and keeping up the pace in a mechanical-like manner, as if they were unaware of what they were doing.”

“The fifth man in the race was old Gilbert Barnes with 478 miles. Despite his week of suffering, the veteran finished strong and yesterday made the best showing of any of the contestants and was given great applause. He walked several laps carrying a Union Jack over his shoulder.”

The race was a great success and none of the runners showed any signs of having received permanent injury. An estimated 41,000 people attended the race during the week and Barnes won $440. After the finish, the men were called out of their tents and led by the band around the track to be cheered by the crowd that had remained in the hall.

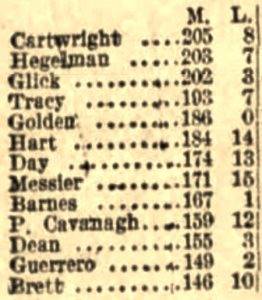

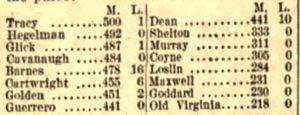

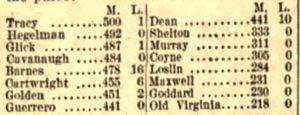

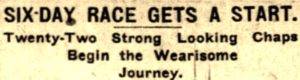

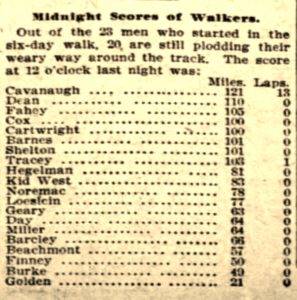

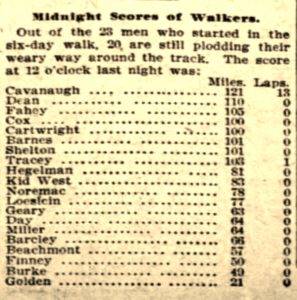

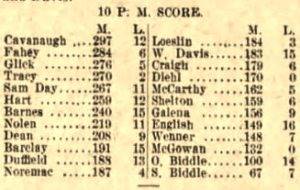

1901 Six-day Race in Pittsburgh

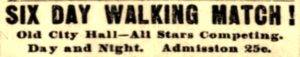

Optimism was strong. “Pittsburgh to all appearances is about to adopt pedestrianism as its favorite sport. The Old City Hall is the scene of a continuous gathering of people who are cheering the weary six-days’ walkers on to top speed. The furious pace that the men set when they were sent off on their death-dealing grind has left its traces. Bleary-eyed, foot-sore and weary, they are defying nature. Every time the band strikes up a lively air, they run like a field of sprinters off on a short dash.”

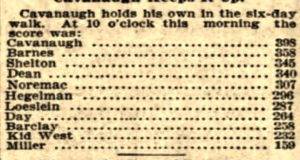

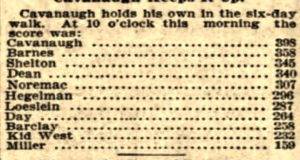

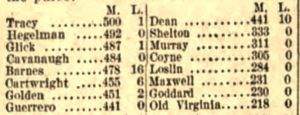

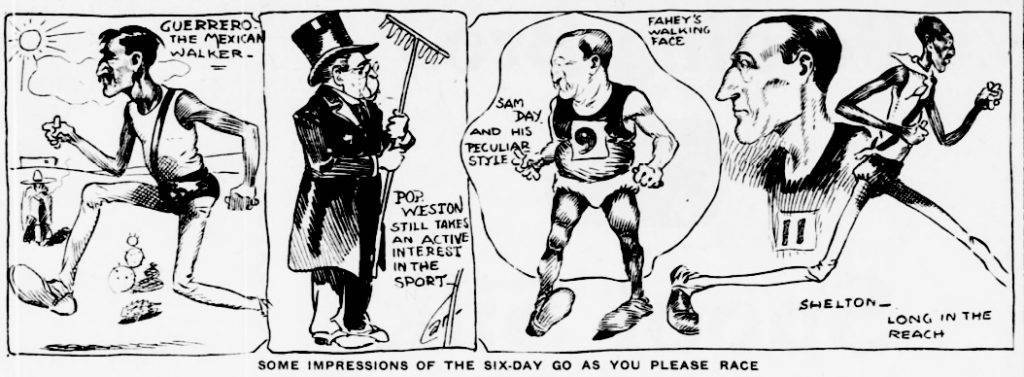

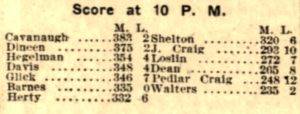

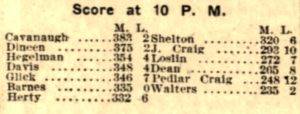

During the first 24 hours, the leader, Patrick Cavanaugh, only left the track long enough for a few “rub downs.” “Barnes, the old man in his sixties, is the marvel of the spectators. He is running at an easy gait and says he will be away up the standings before the end.” Barnes was described as, tall gaunt, specter-like, with a long wisp of grey hair floating out from under his Grand Army helmet like an Indian warrior’s scalp-lock.”

The day 3 report included, “Sixteen men are speeding themselves into premature old age, if not the grave. The 16 physical wrecks are all that remain of the big field of well-trained, bright-eyed athletes who started. The others have fallen by the wayside one by one. Now only the real stars of this sport remain to fight it out for the honors.”

Of the runners still in contention, “all refused to leave the track for fear that some hated rival may cut down the lead they have gained. It is one of the most killing races on record, and just what the future has in store for the men is a matter of guess work.”

“Cranky” runners

Those who followed the sport said that by the 36th hour, typically the runners started acting crazy. “The cranky spell has been reached, and the contestants are furnishing no end of amusement for the spectators. Their tired brains are in a whirl, and it is only to be expected that the men should act like inmates of a ‘funny’ house.”

One runner was so out of it, that he became violent and demanded that he be credited with a mile for every time he covered a 1/20th mile lap. “He claimed that the scorers and spectators had entered into a conspiracy to defraud him and was so demonstrative that his trainers found it advisable to take him out of the race. After a short sleep, he was put aboard a train and sent to his home.”

Others started to act strangely. One imagined that everyone who talked to him was his trainer. Now and then he would call for some gentleman in the crowd to come and give him a rub down. Another asked for a hammer and nails because he said the track ahead of him was springing up. A third was singing most of the time.

“For hours, perhaps, the men will run along without even noticing that they are being watched by interested throngs. Then suddenly, and when least expected, one of them will fly into a fit and rave like a madman.” Dean of Boston, an African American, who was a stenographer by occupation suddenly accused his crew of attempting to poison him. Then he would not accept food from them unless it was first tasted by someone to prove it wasn’t poisoned.

Shelton was given a bottle of ginger ale by his trainer to drink. “While he was gulping down the soft stuff, he yelled out that there was a number of men outside throwing stones through the window at him. Suddenly he threw the bottle through the window, breaking a large pane of glass.”

Tony Loesleine, a tailor, broke down, left the track and went into the crowd. “He asked the spectators to aid him in claiming that his trainers had stolen all his money and clothes. He tried to convince a small group of people that he was a much-abused man, and would have succeeded, had not his trainer arrived on the scene and placed him back on the track, where he continued to run, seemingly well satisfied.”

Band sprints

The runners struggled along in single file until the band played. Then they would start off at a breakneck pace and astonish the onlookers. When the band played a national tune of some kind, a runner who was born there, would demand for the flag of that country and would wave it overhead as he ran like a fury about the track. “Yesterday the band played ‘America’ and Old Man Barnes rushed about with the Stars and Stripes” while another American runner grabbed a tiny flag and ran behind him. “It was a sight to see the two old men sprinting like youths of other days.”

Cavanaugh demanded an Irish flag and threatened to quit the race unless someone got him one. Race management provided him one. “Grabbing it, Cavanugh rushed about the track calling upon the band to play his favorite song, ‘The Wearing of the Green.’ His wish was complied with and such enthusiasm as followed was never witnessed within the confines of Old City Hall. He ran two miles and then placed the flag over his tent.”

The final days of the race

By day 5, the event was deemed as a huge success. ”No event on the calendar of sport held in Pittsburgh in recent years can be compared with the present affair at Old City Hall. Barnes is delighting his fellow townsmen by his game showing. He is now in second place and is likely to stay there, but the old man still has a fighting chance to take the lead from Cavanaugh. All the runners seemed happy, knowing that the home stretch was coming.”

Shelton still imagined that a crowd of enemies was throwing stones through the windows at him. “Suddenly he attacked a tin soldier which was doing picket duty for the advertising department of a big department store. He tore the soldier from the fastenings and while the race managers tried to separate Shelton from the advertising sign, the crowd laughed.” He was taken from the track by his trainers.

The finish

The press covering the race were amazed at what they had witnessed. “It has often been said that a man can endure more hardship, cruelty and physical suffering, and still survive, than any other living being. Its verity has been well exemplified in the six-day grind. The footsore peds are only kept on the track by sheer pluck and gameness, added to force of habit and the use of the most powerful stimulants known to the sporting world.”

Throughout the last day, the interest in the race grew, and the crowds that came exceeded all previous days of the contest. “The last few hours the hall was so crowded that the police had to exert special care to prevent accidents. In the gallery a band played almost continuously. The music was of the crashing kind and added to the dizzy confusion. Announcements regarding the positions of the men were lost in the deafening uproar.” The 2,500 people shouted, cheered and waved hats and flags and the finish arrived.

Patrick Cavanaugh won with 506 miles. Barnes finished second and reached 478 miles. “Barnes, the merry old soldier held his own so well throughout, up to the very end. His staying powers were remarkable, and elicited the applause from his friend. His wife, and grandchildren were present during the closing hours of the race and seemed pleased with the old man’s showing. He finished his entire 478th mile on the run.”

It was reported that Dean, the African American runner, who had reached 412 miles became insane on the last day and was taken to the hospital. He then he escaped his attendants while in the bathroom. “A search was at once instituted and kept up for several hours without finding any trace of the missing racer.” He was later found wandering the streets and was taken to the police station. “His clothing was covered with blood, the result of a hemorrhage from his nose. He was ragged and covered with dirt. He was wholly irrational and babbled meaninglessly. His trainer soon arrived and took the demented man to St. Francis hospital. It is said that Dean is completely broken down from his exertions in the race. He will probably recover after rest and treatment.”

Concluding ceremonies

After the finish, “Cavanaugh appeared on the track in his racing costume and was greeted with wild applause. He is a little man and looked in prime condition. A few moments later, Barnes appeared, staggering a little, but declaring he felt in prime condition” He said that his race was affected by an infected hand due to a rusty nail.

For the closing ceremonies, “The band was brought from the gallery to the front of the hall and stationed on the racer’s track. Patrick Cavanagh was called forth and was formally presented with a new silk hat, and a fine cane. With these he was requested to march around the track once, the band playing ‘The Wearing of the Green’ during the march, while the crowd cheered.”

“Next came Barnes, who took up his position, wearing the G.A.R. uniform and carrying a flag. The band played “Dixie” as he stepped lively and gaily about the track. Barnes waved his flag in high glee.” He won 10% of the gross receipts of the event, $350 (valued at $10,500 in 2019 dollars).

1902 six-day team race in New York City

In 1902, a truly unique race was held at Madison Square Garden on a tiny track of 20 laps to a mile. It was a six-day, two-man relay race. Each team member was allowed to run no more than 12 hours on the track each day. There were 42 teams. Barnes teamed up with Sammy Day to form the “Grand Army Team.”

“Each team had a trainer and two assistants, one for the sleeping quarters and the other for the track side. Besides this each team had a boy to run errands, which made about 250 persons directly concerned with the work on the sawdust track” Adding in the 100 scorers, race officials and building workers, there were 500 men to conduct the big event. A railing had to be placed on both sides of the track to keep everyone away from the contestants, except the trainers.

Race critics

This “go as you please” race started on February 10, 1902. The elite New York City press was highly critical of the race. After twelve hours it was commented, “There are none who look as if they could truthfully be described as going as they pleased. Many are already lame and halting and if there is anything even distantly related to sport in the performance by the rest, it is difficult to find. As an exhibition of forlornness, it is a winner, for a dirtier, more unkempt gang were never before permitted to appear in a public place. Some of the men have not proper clothing and most of the garments are ill-fitting rags, that only half hide the nakedness of the wearers, while a dozen of so are actually clothed in soiled underwear! From the group of tents there emanates the unattractive odor of careless cooking and rubbing ointments impartially mixed. On the track the ‘contestants,’ some of whom are actually said to have been picked upon the streets and transformed from ‘hobos” into ‘pedestrians’ are shifting, slowly and wearily.”

Some New York City editorials despised the thought of reviving that six-day race that had died from its height twenty years earlier. “These protracted tests of physical endurance serve no good purpose. They prove nothing beyond the fact that some men can force themselves to harmful exertion even when every fiber of their physical being is in active revolt. Some of the men are lame enough to be in a hospital and yet they continue to hobble around the track.”

The big fight

On the second day a fight broke out among two of the runners as several thousand looked on. Tom Finerty was sprinting, taking a position near the rail. Gus Guerroro was following him closely, pressing Finerty hard, and seemed to attempt to shove him from his position. “The Irishman turned around and struck Guerrero a stunning blow in the face, felling him.” They knocked each other down several times or the course of several minutes. The police jumped in and separated them.

“The garden was in an uproar as the men were fighting and even the racers halted and joined in the crowd that surround the contestants. After the police broke it up, they all resumed racing but when Guerrero passed Finerty, he struck the Irishman in the face and another fight started for a few minutes.” Both ended up with badly bruised faces. The police notified everyone that they would stop the race and clear the Garden if the trouble wasn’t ended. Ten teams quit by the end of the first day.

Tragic accident

While Barnes was competing, back home in Pennsylvania, Margaret Barnes, his wife, was run down by a large sled near her home. Eight boys in the sled were slightly injured, but Mrs. Barnes was seriously injured and was in a coma. Barnes received the terrible news by telegram and initially continued on in the race, “with his head thrown to one side, he hobbled around the track without a halt” despite being way behind in the standings. But soon he quit when another telegram said his wife was dying. He was given $25 by race management to pay for his expenses home.

In the end, the winning team consisting of two of the best ultrarunners of the time, Peter Hegleman and Patrick Cavanaugh, reached 770 miles. Thankfully, Margaret soon recovered and Barnes quickly made plans to enter another six-day race the next month in Philadelphia. Margaret Barnes would live until 1915.

March 1902 Philadelphia Six-Day

Barnes reached 100 miles in the first day and was in second place. “Old man Barnes still keeps up a steady pace and is surprising all hands by his wonderful vitality.” During the afternoon, some runners protested the scoring. Stopping before the immense scoreboard, they lost many minutes of precious time in arguing about the distance covered. “Several of them claimed that they had been robbed of laps, but in every case the trouble was straightened out.” One runner refused to continue until he was given credit for three laps. “After a stormy scene he consented to continue.” Thankfully we have timing chips in modern times.

Many of the men were getting quite cranky and would often do some funny stunts. “Barclay appeared on the track wrapped in a blanket and fought his trainers when they tried to take it away from him. Some complained of the excessive heat, while others contended that the place was cold.”

Attendance was good and the hall was filled each evening. Sometimes the crowd was four-deep on the rails. Every time a man added a mile to his score, he was loudly applauded. “A scramble took place this morning when a wealthy enthusiast threw money on the track just in front of an approaching bunch who eagerly sprinted to secure the prize.”

On day 4, Max Diel fell on the track and was badly injured by being kicked in the hip by another runner. He was taken to the hospital. The leader, Pat Cavanaugh fainted and fell on his face on the track. “Without any warning, he suddenly reeled, and fell forward heavily on his face, throwing the spectators in the greatest excitement possible. He was picked up instantly and carried to his dressing room, where he revived in a few minutes.” The doctors checked him out and soon he was back on the track.

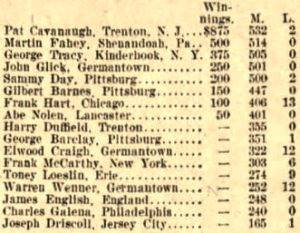

Cavanaugh won with 532 miles. It was said, “The suffering endured by the men during the race has been worse than in any previous contest of this kind, owing to the terrific pace set by the leaders and kept up during the entire week.”

November 1902 Philadelphia Armory Six-Day

Barnes was among 17 runners who started a six-day race at the Third Regiment Armory in Philadelphia on November 3, 1902. “The armory is fixed up in excellent style for the race. The track is an oblong one, being ten laps to a mile and packed down hard with a combination of sawdust and dirt.” As usual Barnes passed 100 miles on the first day. “Barnes is arousing more interest among the spectators than any other walker. The old pedestrian keeps grinding away in a swinging walk, looking neither to the right or left, cutting off the laps with a regularity of a moving pendulum.”

After 69 hours, Barnes was at 246 miles and less than one mile behind that leader. “Gilbert Barnes is rather ‘dopey’ owing to his almost continuous stay on the track. Early this morning he ran two laps backward, finally running into the railing that surrounds the scorer’s box. The collisions seemed to bring him to his senses and he started off in his usual manner.” Near the end of day 5, he passed 400 miles and was just five laps behind Abe Nolan. But Nolan went on to win with 474 miles to Barnes’ 470

1903 Six-Day in Philadelphia – Weston Challenge Belt

On February 23, 1903, Barnes ran in the Weston Challenge Belt Six-Day in the Industrial Art Hall in Philadelphia with 28 runners. “The field is entirely too big for the size of the track and many of the walkers are uncomfortably crowded as they walk around. Tents for the use of the ‘peds’ take up three sides of the hall and with the tan and sawdust track and with the usual vendors’ stands, remind one of the circus.”

On day 4, the race was thrown into turmoil. John Glick was struggling to hold on to third place. After he was passed by a runner, he “began to lose control of himself.” A runner, Davis, was next to try to go ahead and the two became involved in a “hot spurt” for a full mile. Finally, Glick was forced to quit the furious pace and when Davis went by him, Glick struck him in the back of the neck, knocking him down. Davis got up and retaliated, hitting Glick squarely in the face.

Others, both runners and trainers joined in the riot. “Several spectators leaped over the railing and followed suit, and an all round rough house ensued. The other racers were brought to a standstill and there was a general stampede on the part of spectators in other parts of the building to the scene of the fight.” The police took control and within a few minutes the runners were again going around the track. “Davis was cheered by the crowd, while jeers and catcalls were hurled at Glick, who sought refuge in his tent.” He later apologized to Davis.

1903 Philadelphia Six-Day Relay

On November 16, 1903, Barnes participated in a six-day two-man relay race in Industrial Art Hall in Philadelphia on the 17-lap-per-mile track. He was teamed up with Tony Loslein. Barnes and Loslein finished in 5th with 653 miles. The winning team reached a staggering 748 miles. After the race, the winning team was paraded to a hotel, led by a band, and through a blazing scene of fireworks and Chinese lanterns as more than a thousand enthusiastic fans cheered.

1905 Pittsburgh 72-hour Race

By 1905 Pennsylvania passed a law making six-day races illegal, which halted the six-day race comeback in that city. Like New York, races could not be more than 12 hours during a day. In early 1905 people thought Barnes was well over 70 years old even though he was only 58. He was convinced to enter a six-day 72-hour race, running twelve hours a day held in the Old City Hall in Pittsburgh. He said, “This is not my style of race. I can make a better showing in a 142-hour contest, and I am afraid I won’t have much chance with some the young fast men entered, but I’ll guarantee to cover 350 miles during the week.” The world record for this type of race was thought to be 432 miles, with the American record at 417 miles held by Gus Guerero set in 1892.

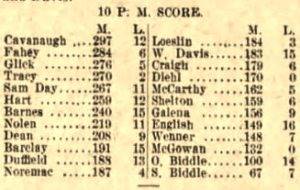

The race started on February 6, 1905 at 1 a.m. On Day 5 it was reported, “Gilbert Barnes met with an accident last night. All day long he had been making an awful battle with John Craig for eighth place. When Craig was within a few laps, Barnes fell near his training corner from sheer exhaustion and was picked up unconscious. He was brought to quickly, as not a moment could be spared from the track if he was to hold the coveted position and he pluckily took to the track at once.” In the end, Barnes reached an impressive 325 miles for 9rh place, just out of the money. Patrick Cavanaugh won with 365 miles.

But unfortunately, the race was not a financial success and signaled further that the six-day race would die. “It is not at all likely that the men who took part in the 72-hour walking contest in Old City Hall last week will ever consent to play a return engagement in Pittsburgh. Viewed from a financial standpoint, the affair was what the dramatic editor would term, a ‘frost.’”

The press joked about how boring six-day races had become for spectators. “A six-day race is always enjoyable until the band wakes you up.” Also, “One of the six-day racers slept for two days after the race was over. Some of the spectators beat him by four days.”

Entering his 60s.

As with other ultrarunners of the era, Barnes greatly embellished his resume to the press. In 1911 he said he had won five ultra distance races in Pittsburgh, 10 races in Philadelphia, won in Madison Square Garden, and won first place in St. Louis (he actually placed 3rd). While Barnes was a world-class multi-day runner, no evidence has been found in newspapers that he ever came away with any wins.

1918 500-mile to Virginia

Barnes said, “The lads gave me a great reception. I only remained a short time in camp. I took my supper in the mess with the boys and afterwards was given a rousing sendoff. The soldiers sang for me and gave three cheers for me as I left.”

Stricken with Cancer

![]()

![]()

Death

Sources:

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pennsylvania), Apr 19, 1898, Feb 12, 1900, May 1, 1919

- The Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania), Apr 19, 1898, Feb 12, Apr 11, May 6,8 Jun 19, 1899, Mar 31, 1900, Oct 31, 1901, Feb 13, 1905, Feb 19, 1909, Dec 14,24, 1911, Jun 17, 1914, Feb 18, 1916,Dec 30, 1916, Mar 18-29, 1918, Ap 9, 1918, Nov 10-17, Jan 10, 1919, Mar 20, 1919, May 1, 1919.

- Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pennsylvania), Apr 19, 21-22, May 18,22,25, Aug 1, 189, Apr 27, 1899, Feb 18,28, 1900, Mar 30, 1900, Aug 22, 1900, Mar 11, 1901, Oct 16, 1901, Nov 10-17, 1901, Mar 17, 19, 1902, Feb 11-12, 1905, Dec 27, 1906, Feb 19, 1909, April 12, 1909, Mar 10, 1911, Dec 14, 1911, Jun 15, 1913, Jan 10, 1919

- Wilkes-Barre Times Leader (Pennsylvania), Apr 8, 1899, Mar 15, 1901, Nov 18, 1903

- Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (Pennsylvania), Aug 11, 1874

- The Pittsburgh Commercial (Pennsylvania), May 1, 1876

- Centre Democrat (Pennsylvania), Apr 1, 1880

- The Indiana Progress (Pennsylvania), Mar 13, 1884

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Jun 11, 1899, Mar 12-17, Nov 17, 1901, Nov 3-10, 1902, Feb 23-29, 1903

- The Brooklyn Citizen (New York), Jun 11, 1899

- The Times (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Jun 4, 1899, Mar 12, Oct 7-15, 1901, Feb 14, 1902, Mar 10-17, 1902

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Jun 13, 1899

- Buffalo Evening News, Jun 13, 1899

- The Sun (New York, New York), Jun 13, 1899

- The New York Times, May 9, Jun 13, 1899

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), May 10-11, 14, 1899, Jun 24, 1900

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Feb 6,14, 17, 1900

- Louis Globe-Democrat (Missouri), Feb 12-13, 1900

- New Castle News (Pennsylvania), Feb 12, 1902

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Feb 3, 1902, May 27, 1912

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Feb 10-14, 1902

- New York Tribune, Feb 11, 1902

- Miners Journal (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Mar 13, 1902

- Harrisburg Daily Independent (Pennsylvania), Mar 14, 1902

- The Daily Notes (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania), Sep 1, 1902

- Republican and Herald (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Nov 17, 1903

- Altoona Times (Pennsylvania), April 2, 1909

- Lancaster Intelligencer (Pennsylvania(, Sep 20, 1913

- The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), May 26, 1912

- The Daily Courier (Connellsville, Pennsylvania), Mar 21, 1918

- New Castle News, Aug 16, 1916