Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:10 — 42.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

Stu Mittleman was the sixth person to be inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. During the 1980s, while a college professor from New York, he became the greatest multi-day runner in the country who won national championships running 100 miles, but ran much further than that in other races. During that period, no other American ultrarunner, male for female, exhibited national class excellence at such a wide range of ultra racing distances. He brought ultrarunning into the national spotlight as he appeared on national television shows and became the national spokesman for Gatorade.

Stu Mittleman was the sixth person to be inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. During the 1980s, while a college professor from New York, he became the greatest multi-day runner in the country who won national championships running 100 miles, but ran much further than that in other races. During that period, no other American ultrarunner, male for female, exhibited national class excellence at such a wide range of ultra racing distances. He brought ultrarunning into the national spotlight as he appeared on national television shows and became the national spokesman for Gatorade.

| Learn about the rich and long history of ultrarunning. There are now eleven books available in the Ultrarunning History series on Amazon, compiling podcast content and much more. Learn More. If you would like to order multiple books with a 30% discount, send me a message here.

|

Stuart “Stu” M Mittleman was born in New York City in 1951 to Irving Jacob Mittleman (1924-2009) and Selma R (Mitzner) Mittleman (1929-2023). His Mittleman grandparents were Jewish Russian immigrants who came to America in 1913.

Stuart “Stu” M Mittleman was born in New York City in 1951 to Irving Jacob Mittleman (1924-2009) and Selma R (Mitzner) Mittleman (1929-2023). His Mittleman grandparents were Jewish Russian immigrants who came to America in 1913.

When he was in high school in Dumont, New Jersey in the late 1960s, he was on the track team and ran the mile in 4:39 mile, the half mile in 2:01. He was better at wrestling in which he lettered and was a district champion. At the University of Connecticut, he continued wrestling for one season but switched to long-distance swimming and weightlifting. At Colgate University, he was on the dean’s list and earned his bachelor’s degree in liberal arts. He earned his master’s degree at the University of Connecticut. He was a heavy smoker during school, going through two packs of cigarettes per day.

During the early ‘70s, he became disillusioned with the state of the country during the Vietnam War era and spent time on the West Coast, where he took up running again “for his head.” But while skiing in 1975, he had a terrible fall, tore his ACL and damaged cartilage. He had knee surgery and could not run for five months. When he could run again, he did it for relaxation and to find a quiet time for himself.

Becomes a Marathon Runner

In 1977, he ran up Flagstaff Mountain in Boulder, Colorado and fell in love with running. He went into a running store and asked how he could sign up for the Boston Marathon, three months away. They told him he needed to qualify, so he ran Mission Bay Marathon in San Diego with a qualifying time of 2:46. Early into his dream race at Boston, he was running in a drainage ditch in efforts to pass runners and twisted his ankle terribly. Disappointed, but determined, he tied ice around his swollen ankle and vowed not to drop out of the race. He finished in 4:03. He returned to Boston the next year and finished in 2:31:11. After finishing the New York City marathon six months later in 2:33:00, he couldn’t understand why he couldn’t run any faster, even though he was never tired at the end of his races. “I just started thinking, why did I have to stop? I wondered how much longer I could have run.” This thought made him turn to “the longer stuff.

First Ultramarathon

Mittleman was 5’ 8” and about 140 pounds. As a graduate student in sports psychology at Columbia University, Mittleman ran his first ultra in 1978, running 6:11 in the Metropolitan 50 in Central Park, New York. That year the race was poorly organized, and the front-runner went off course, but he placed 8th with 6:13. “I ended up sprinting the last 10 miles and I was hooked.” He liked ultras better than marathons because they were less competitive and they had a friendlier atmosphere.

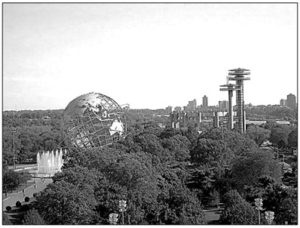

The 1979 Unisphere 100

With that elite performance, he qualified to enter the 1979 Unisphere 100, held at Flushing Meadows in Queens, New York, on a 2.27-mile loop road course around Meadow Lake. This 100-miler was first held in 1978, won by Park Barner in 13:57:36. In 1979, it was the TAC 100 Mile National Championship. The races’ namesake, the Unisphere, a massive spherical steel representation of the Earth, was created as part of the 1964 World’s Fair.

With that elite performance, he qualified to enter the 1979 Unisphere 100, held at Flushing Meadows in Queens, New York, on a 2.27-mile loop road course around Meadow Lake. This 100-miler was first held in 1978, won by Park Barner in 13:57:36. In 1979, it was the TAC 100 Mile National Championship. The races’ namesake, the Unisphere, a massive spherical steel representation of the Earth, was created as part of the 1964 World’s Fair.

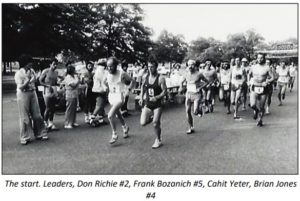

The race had strict qualifying requirements and the cutoff time to finish 100 miles was set to a very difficult 18 hours. It was said, “qualifying times were established to weed out any who might hurt themselves by trying something they weren’t ready for, or who hadn’t the potential to finish within the time limit.” Headlining the race that year was the 100-mile track world record holder, Don Ritchie, from Scotland.

The race had strict qualifying requirements and the cutoff time to finish 100 miles was set to a very difficult 18 hours. It was said, “qualifying times were established to weed out any who might hurt themselves by trying something they weren’t ready for, or who hadn’t the potential to finish within the time limit.” Headlining the race that year was the 100-mile track world record holder, Don Ritchie, from Scotland.

Mittleman said, “When I first considered 100 miles, I thought it was impossible. When I found out that people were doing it, it forced me to re-think that. The toughest decision was to go out and attempt it.”

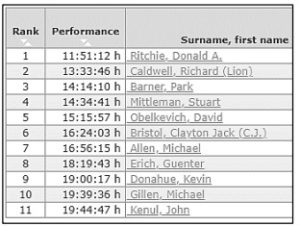

In all, there were 27 starters, including many of the best ultrarunners in the country. As expected, Richie won and set a world 100-mile road record of 11:51:12. Mittleman reached 50 miles in 7:02:44. “At 60 miles, I was farther than I had ever run. Anxiety and fatigue overcame me, and I was ready to drop out. I decided to walk a lap. While I was walking, I felt rejuvenated, and I started to walk again. At that point, I stopped being in awe of the distance and did what I had to do.” He finished in fourth place with an impressive 14:34:14.

In all, there were 27 starters, including many of the best ultrarunners in the country. As expected, Richie won and set a world 100-mile road record of 11:51:12. Mittleman reached 50 miles in 7:02:44. “At 60 miles, I was farther than I had ever run. Anxiety and fatigue overcame me, and I was ready to drop out. I decided to walk a lap. While I was walking, I felt rejuvenated, and I started to walk again. At that point, I stopped being in awe of the distance and did what I had to do.” He finished in fourth place with an impressive 14:34:14.

The 1980 New York Invitational 100 Mile Run

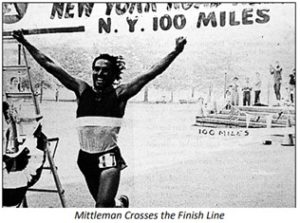

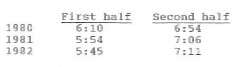

In 1980, this 100-miler continued to be held on the Flushing Meadows Park loop, put on by the New York Road Runners Club (NYRRC), but was rebranded as “NYRR New York Invitational 100 Mile Run.” The 1980 race was still a restricted invitational and for this year it was said to include the most elite field for any American ultra. There were 29 starters. “Mittleman had been in 8th place at 14 miles, but by 37 miles had advanced to the head of the class. It was a position he never relinquished, carving out a comfortable 14-minute lead by his 50-mile split at 6:11:41. Eventually it ballooned to over 42 minutes at one point.” During the night he started hallucinating, seeing himself as an ancient Greek, running through the streets of Athens.

In 1980, this 100-miler continued to be held on the Flushing Meadows Park loop, put on by the New York Road Runners Club (NYRRC), but was rebranded as “NYRR New York Invitational 100 Mile Run.” The 1980 race was still a restricted invitational and for this year it was said to include the most elite field for any American ultra. There were 29 starters. “Mittleman had been in 8th place at 14 miles, but by 37 miles had advanced to the head of the class. It was a position he never relinquished, carving out a comfortable 14-minute lead by his 50-mile split at 6:11:41. Eventually it ballooned to over 42 minutes at one point.” During the night he started hallucinating, seeing himself as an ancient Greek, running through the streets of Athens.

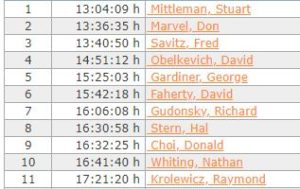

Mittleman experienced a mild slump near the end that prevented him from breaking 13 hours. He finished in 13:04:09, which was the second-fastest American 100-mile time in history at that point. He became the 100-mile national champion.

Mittleman experienced a mild slump near the end that prevented him from breaking 13 hours. He finished in 13:04:09, which was the second-fastest American 100-mile time in history at that point. He became the 100-mile national champion.

He told the New York Times, “I’m compulsive, obsessive. I seem to always have to try to do more and go farther. This 100-mile race is a good test of yourself. Everyone seems to be running the marathon. The ultramarathon is something different. Running gives a person a chance to explore themselves. Some really get heavily involved in it. For others, it’s like a form of relaxation and a chance to grow healthier.”

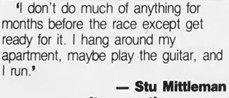

In the fall of 1980, Mittleman moved to Manhattan’s upper west side and could be seen running 120-200-mile weeks through Central Park, along Broadway, and along the avenues south to Battery Park. He said, “I like hopping over garbage cans and getting to know all the dogs in the neighborhood. It makes the whole experience less tense. If I run through Chinatown and Little Italy, I really feel like I’m taking a trip.”

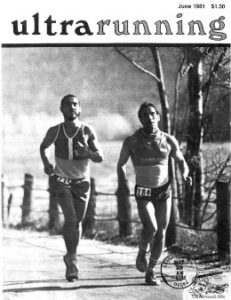

The 1981 New York Invitational 100 Mile Run

In late 1980, at the age of 29, Mittleman experienced bad pain in his damaged knee from his 1975 skiing accident. He took time out and tried everything, but after several months, still couldn’t run. He finally went to an orthopedic surgeon who gave him the bad news that he had no cartilage and had an arthritic knee of a much older man. He told him to stop running. Mittleman couldn’t accept that and resorted to other physical therapy treatments and improved health. Things improved and in April 1981, he was able to run 30 miles a day again.

In late 1980, at the age of 29, Mittleman experienced bad pain in his damaged knee from his 1975 skiing accident. He took time out and tried everything, but after several months, still couldn’t run. He finally went to an orthopedic surgeon who gave him the bad news that he had no cartilage and had an arthritic knee of a much older man. He told him to stop running. Mittleman couldn’t accept that and resorted to other physical therapy treatments and improved health. Things improved and in April 1981, he was able to run 30 miles a day again.

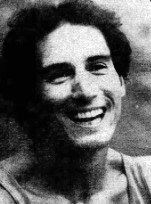

Mittleman was teaching history and sociology of sports in the health and physical education department of Queens College. He was also an adviser to a master’s degree program in athletic coaching at Columbia University, working on his doctorate in education in the field of sports psychology. He said, “Among the things I am working on is how emotions and personality effects an athlete’s physical ability. I can teach coaches to use that knowledge to train athletes.”

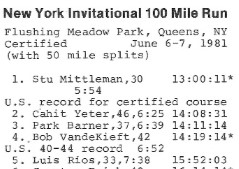

There were 38 starters at the 1981 100-mile invitational race at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. “The small area behind the amphitheater reminded one runner of his Army camping days before inspection with tents, blankets, and sleeping bags all scattered about.” Mittleman reached 25 miles in second place with 2:52:00. The race was hot and humid and an ambulance had to be called for one runner. Mittleman really wanted to break the American record for 100 miles but tightened up for the last five miles. “Though he slowed from record pace, Mittleman still won the race in 13:00:11. The hardest part of the race for him? ‘The gnats at sundown, I swallowed a bunch of them.’ ‘Thought you were a vegetarian,’ someone quipped.’ He won a silver champagne bucket trophy for his efforts.

There were 38 starters at the 1981 100-mile invitational race at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. “The small area behind the amphitheater reminded one runner of his Army camping days before inspection with tents, blankets, and sleeping bags all scattered about.” Mittleman reached 25 miles in second place with 2:52:00. The race was hot and humid and an ambulance had to be called for one runner. Mittleman really wanted to break the American record for 100 miles but tightened up for the last five miles. “Though he slowed from record pace, Mittleman still won the race in 13:00:11. The hardest part of the race for him? ‘The gnats at sundown, I swallowed a bunch of them.’ ‘Thought you were a vegetarian,’ someone quipped.’ He won a silver champagne bucket trophy for his efforts.

Mittleman refused to walk during 100-mile races. He said, “There’s no great secret to running 100 miles. I start out by treating it as a 100-kilometer race. When I get to 100 kilometers, which is 62 miles, I tell myself there are only 40 miles to go. You can’t practice running 100 miles to make the experience less awesome. There’s no way to water it down, so you go into it not knowing what to expect.”

When asked if he feared competition from top marathoners, he said, “Those guys are used to all the money under the table, the media spotlight, and the glory. Besides, they know if they run one ultra, they’ll probably finish themselves in the marathon for the rest of the year. It’s just not worth it to them.”

When asked if he feared competition from top marathoners, he said, “Those guys are used to all the money under the table, the media spotlight, and the glory. Besides, they know if they run one ultra, they’ll probably finish themselves in the marathon for the rest of the year. It’s just not worth it to them.”

The 1982 New York Invitational 100 Mile Run

The 1982100 Mile Championship was moved to Shea Stadium to help promote more publicity for the sport. The start/finish line was between third base and home plate. The course ran around on the baseball warning track for a quarter mile and then out in the parking lot in a three-quarter mile question-mark loop, avoiding six-inch puddles from rain. “Aside from a few unavoidable puddles, the lot was fine, but after only a few miles, the clay and cinder warning track became a quagmire. A few strategically dumped wheelbarrows’ worth of heavy-grain sand in mid-race helped a bit, but at least 200 yards per loop consisted of sticky, slippery, inch-thick goo for most of the race.” The lap counters used the Met’s dugout for shelter from the rain.

The 1982100 Mile Championship was moved to Shea Stadium to help promote more publicity for the sport. The start/finish line was between third base and home plate. The course ran around on the baseball warning track for a quarter mile and then out in the parking lot in a three-quarter mile question-mark loop, avoiding six-inch puddles from rain. “Aside from a few unavoidable puddles, the lot was fine, but after only a few miles, the clay and cinder warning track became a quagmire. A few strategically dumped wheelbarrows’ worth of heavy-grain sand in mid-race helped a bit, but at least 200 yards per loop consisted of sticky, slippery, inch-thick goo for most of the race.” The lap counters used the Met’s dugout for shelter from the rain.

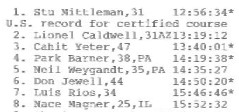

The New York Times published a long article about Mittleman and established him as the favorite. The race was filmed by CBS, and ABC’s Good Morning America planned to have the winner on their show. Mittleman and Lion Caldwell, a doctor from Cibecue, Arizona, sought after that opportunity, and battled intensely. Forty-five men and three women started. Mittleman led the entire race. He reached 50 miles in 5:45:00 with a two-mile lead over Caldwell and said, “From 50 to 75 we were both really pressing. Oh, we were racing so hard in there, neither one of us ever letting up, it was crazy.” Mittleman refused to give up his two-lap lead.

The New York Times published a long article about Mittleman and established him as the favorite. The race was filmed by CBS, and ABC’s Good Morning America planned to have the winner on their show. Mittleman and Lion Caldwell, a doctor from Cibecue, Arizona, sought after that opportunity, and battled intensely. Forty-five men and three women started. Mittleman led the entire race. He reached 50 miles in 5:45:00 with a two-mile lead over Caldwell and said, “From 50 to 75 we were both really pressing. Oh, we were racing so hard in there, neither one of us ever letting up, it was crazy.” Mittleman refused to give up his two-lap lead.

Mittleman commented about the mud on the warning track, “I don’t run too well in the rain, and I run better when it’s hot. I think the best running I did last night was from the 50-mile to the 75-mile point. It was like running in glue. The mud was treacherous and there is no doubt that the race took its toll on me. I’ve never competed under these kind of conditions.”

Mittleman commented about the mud on the warning track, “I don’t run too well in the rain, and I run better when it’s hot. I think the best running I did last night was from the 50-mile to the 75-mile point. It was like running in glue. The mud was treacherous and there is no doubt that the race took its toll on me. I’ve never competed under these kind of conditions.”

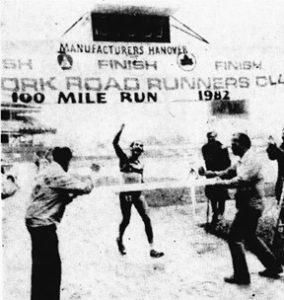

It was reported, “During the last five hours, the warning track slime became so bad that handlers had difficulty walking through it.” It was also said that Mittleman changed shirts about 40 times during the event. He won with an astonishing 12:56:34 in the rain and came within two minutes of breaking Jose Cortez’ long-standing American 100-mile record. He said, “The degree of agony and discomfort might have been the worst I’ve experienced to date, yet I managed to hold on to the fast early pace and win.” He ran a victory lap as a CBS reporter interviewed him. Sue Medaglia, from New York City, finished first among the women, with 18:43:07.

It was reported, “During the last five hours, the warning track slime became so bad that handlers had difficulty walking through it.” It was also said that Mittleman changed shirts about 40 times during the event. He won with an astonishing 12:56:34 in the rain and came within two minutes of breaking Jose Cortez’ long-standing American 100-mile record. He said, “The degree of agony and discomfort might have been the worst I’ve experienced to date, yet I managed to hold on to the fast early pace and win.” He ran a victory lap as a CBS reporter interviewed him. Sue Medaglia, from New York City, finished first among the women, with 18:43:07.

The race took its toll on Mittleman. For three hours after finishing, he could not stand up. “He needed two helpers to shuffle to a car. Speech slowed and slurred, he confessed, ‘I’m just devastated. Well, maybe I left the best part of myself out there today. I’ve never felt this way after a race. I guess it comes with the territory.” His win was awarded the Ultrarunning Performance of the Year by Ultrarunning Magazine. He received national attention and had a live interview on CBS after a boxing match. With that national exposure, he was hired to become the national spokesman for Gatorade.

The 1983 New York Invitational 100 Mile Run

In 1983 Mittleman set a goal to win the 100-mile Championship at Shea Stadium for the fourth time in a row. To prepare for the 100-miler, he used the Boston Marathon for a “sharpener” and then ran Lake Waramaug 100K. He averaged about 110 miles training per week but started concentrating on more intense workouts. He had a positive attitude: “I could enter the next 100-mile race, and somebody could beat me, but they don’t defeat me; they just do better than me that particular day. I’ve come in second a lot more times than I’ve come in first, and it didn’t diminish the feeling.”

In 1983 Mittleman set a goal to win the 100-mile Championship at Shea Stadium for the fourth time in a row. To prepare for the 100-miler, he used the Boston Marathon for a “sharpener” and then ran Lake Waramaug 100K. He averaged about 110 miles training per week but started concentrating on more intense workouts. He had a positive attitude: “I could enter the next 100-mile race, and somebody could beat me, but they don’t defeat me; they just do better than me that particular day. I’ve come in second a lot more times than I’ve come in first, and it didn’t diminish the feeling.”

He came to Shea Stadium ready to compete against the huge field of 90 runners. But during the early stages of the race, a volunteer on a bike, delivering water to the aid station, crashed into Mittleman. After 57 miles, he quit from groin injuries resulting from the crash. Ray Scannell, of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, won in 13:06:02.

He came to Shea Stadium ready to compete against the huge field of 90 runners. But during the early stages of the race, a volunteer on a bike, delivering water to the aid station, crashed into Mittleman. After 57 miles, he quit from groin injuries resulting from the crash. Ray Scannell, of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, won in 13:06:02.

Mittleman Dominates in Shorter Ultras

Mittleman used various shorter races to train for his 100-milers and multi-day races. At times, he would run and win races every other week. In 1981, he won the Lake Waramaug 50 Mile in 5:14:05, becoming #5 on the all-time U.S. list. In 1982 he ran a 6:57 at Lake Waramaug 100K, setting a course record that stood until 1994.

Mittleman used a unique approach when he would feel cramping starting during a race. “I try to visualize the muscles, the way they’re constructed and how they work. I focus my attention on the vision for some time and try to visualize the tension. Finally it does away.”

Mittleman liked to hang out at the finish line until the last runner completed a race. He said, “People who run ultramarathons are real sensitive to each other. They reach out to each other. It’s something very unusual that they each have in common. It is the runners that take the longest to finish that should be congratulated. They have more courage. Their only reason for running is to find out something about themselves.”

Mittleman liked to hang out at the finish line until the last runner completed a race. He said, “People who run ultramarathons are real sensitive to each other. They reach out to each other. It’s something very unusual that they each have in common. It is the runners that take the longest to finish that should be congratulated. They have more courage. Their only reason for running is to find out something about themselves.”

1983 New York Six-Day Race

In 1980, six-day races were reestablished after a 60-year absence. In 1983, the 6-day race came to New York City, put on by the New York Road Runners Club. It was to be held at Downing Stadium on Randalls Island. Mittleman decided to sign up. Fred Lebow, president of the NYRRC, was delighted and arranged to have Mittleman featured on ABC’s Night Line each night to be interviewed by Ted Koppel. Asked about what he would bring to the race, Mittleman joked, “I was thinking of bringing a portable television. I also thought about bringing my guitar. Then I decided that any time I spent in the tent should be with my eyes closed.”

In 1980, six-day races were reestablished after a 60-year absence. In 1983, the 6-day race came to New York City, put on by the New York Road Runners Club. It was to be held at Downing Stadium on Randalls Island. Mittleman decided to sign up. Fred Lebow, president of the NYRRC, was delighted and arranged to have Mittleman featured on ABC’s Night Line each night to be interviewed by Ted Koppel. Asked about what he would bring to the race, Mittleman joked, “I was thinking of bringing a portable television. I also thought about bringing my guitar. Then I decided that any time I spent in the tent should be with my eyes closed.”

Mittleman, working on his PhD in sports psychology at Columbia University, was a rookie at multi-day races and first just went with a strategy to run as long as he could, rest and then run again. By 36 hours without sleep, he was a mess and only covered five miles in seven hours. He said, “I was hallucinating. The track temperature was 104 degrees and it was red clay. I felt like I was in a groove on a big muddy turntable (record player). I didn’t feel part of this planet.” A fellow ultrarunner told him to observe Sigfried Bauer, of New Zealand, who was using a strategy of running hard four hours, resting, and then repeating. Mittleman changed his strategy and things eventually came together. He said, “Toward the end, I found that it was more uncomfortable to rest in my tent than to be on the track with the other runners. The race became not a matter of individual will, but of community effort.” He went on to set a modern era six-day American Record of 488 miles, but came in short of Bauer’s winning distance of 511 miles. (The overall six-day American record was held by James Albert Cathcart, with 621.7 miles, set in 1888).

1984 New York Six-Day Race

In a historic 1984 six-day race in New York City, Mittleman was the local favorite and got a lot of publicity. But he had what he considered a poor race with 502 miles, finishing 7th in a highly competitive race with 17 runners covering more than 400 miles. Yiannis Kouros of Greece, set a World Record and Mittleman had severe post-race depression with a foot problem. He wrote, “Searching for reasons, I could only conclude that my breakdown was the inevitable outcome of running as many miles as I did. I did not even for a moment, consider that my diet might have something to do with how I felt.” He met with Dr. Phil Maffetone who tried to convince him to get sugar out of his diet, eat more oils, and dramatically increase his consumption of water. Mittleman took the advice and a month later was back competing well. The theory was, “you need to eat fat in order to burn fat.”

Six-Day Race in France

Two months later he was recovered and headed for La Rochelle, France, to run a 6-day race on an indoor 200-meter paved track inside an exposition hall. In the middle of the track was a restaurant and all sorts of entertainment. One runner said, “It is as if we are on show all the time.” Thousands of people showed up for the opening ceremonies. Twenty runners had been invited to compete, and in the days leading up the race, they made visits to schools and businesses. Mittleman decided to incorporate a new strategy for his six-day race. He would walk the first hour, run the next five, and repeat. He said, “The event begins, and the runners are off. The crowd roars and the music blares thunderously on. What do I do? I start walking. The crowd begins to yell, but not in support. I manage to hear taunts of ‘Yankee, go home.’ Mixed in with the more universal and easy to understand ‘boo.’” By the end of the first hour, he was in dead last, but when he ran, he would catch up, and then fall behind again as he walked. After two days, he was in the bottom third of the field. But on day three, he was able to run faster than anyone else. By the end of day four, he was closing in on the leaders. He moved into second place, but was too far behind to win. He finished in second place with 571 miles, setting a new modern-era American Record (50 miles behind the all-time American record set in 1888). After the race, a spectator that came every day came up to him and said, “I have never seen a race like that before, Bravo Mittleman.”

More Six-Day Races

Mittleman had his sights on breaking 600 miles during six days, an accomplishment that only three Americans in history had achieved, doing it nearly 100 years earlier. He felt that he could do it at the 1984 Rocky Mountain 6-day race run at altitude in Boulder, Colorado. It was held in the University of Colorado Fieldhouse on a tiny 220 yard track. It was observed that every minute of every day of Mittleman’s run was planned and accounted for, including every meal. He ran an amazing 215 miles during the first two days, determined to break 600 miles. But on day five, he developed Achilles tendon problems because of shoes that were too small, and had to walk the rest of the way. He did extend his personal best to 577 miles. This had been Mittleman’s third six-day race in six months and he exceeded 500 miles in all of them. He commented, “We’re still learning about 6-day racing.” (In 1899, George Noremac, also of New York City, concluded his six-day racing career with 16 six-day races with more than 500 miles, the most 500+ finishes in history.)

In early 1985, Mittleman ran in the New Astley Belt race held at El Cajon, San Diego, California. He ran 124 miles on the first day, but the heat slowed him down and after four days, he was not being pushed by any competition and ended up with 534 miles to win that race by 111 miles. One onlooker commented about the heat’s effects on the runners, “Their lips looked like their feet.” In June 1985, he ran in the sixth-annual Edward Payson Weston Six Day Track Race held in New Jersey. He unexpectedly dropped out while leading with 191 miles on the second day.

The 1986 1,000-mile race

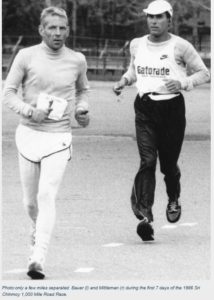

In 1986, Mittleman ran in a historic 1,000-mile race and battled the famed World Record holder, Siegfried Bauer, of New Zealand, for nearly 11 days at Flushing Meadows on a one-mile course that consisted of an out-and-back lap and was barricaded to keep separated from the thousands of park visitors who would stop to see what was going on. There were thirteen competitors. Bauer was determined to defend his World Record. Don Choi, of San Francisco, was also there to defend his American Record set the previous year. Mittleman was ready to compete.

In 1986, Mittleman ran in a historic 1,000-mile race and battled the famed World Record holder, Siegfried Bauer, of New Zealand, for nearly 11 days at Flushing Meadows on a one-mile course that consisted of an out-and-back lap and was barricaded to keep separated from the thousands of park visitors who would stop to see what was going on. There were thirteen competitors. Bauer was determined to defend his World Record. Don Choi, of San Francisco, was also there to defend his American Record set the previous year. Mittleman was ready to compete.

After the first day, Bauer had the lead, four miles ahead of Mittleman, who had run 116 miles. After six days, he was behind Bauer by ten miles with 503. But then he ran the second 500 miles faster than the first and went into first place near the end of day seven. On the tenth day, they were battling for hours during the night, each determined to stay on the course at all costs. They both believed that the first one to walk off the course would be conceding the win. To Mittleman’s surprise, Bauer stopped running and went off into his tent. Mittleman had a 30-mile lead at the point and came away the victor with a time of 11 days, 20 hours, and 36 minutes. He lowered Bauer’s World Record by 16 hours.

After the first day, Bauer had the lead, four miles ahead of Mittleman, who had run 116 miles. After six days, he was behind Bauer by ten miles with 503. But then he ran the second 500 miles faster than the first and went into first place near the end of day seven. On the tenth day, they were battling for hours during the night, each determined to stay on the course at all costs. They both believed that the first one to walk off the course would be conceding the win. To Mittleman’s surprise, Bauer stopped running and went off into his tent. Mittleman had a 30-mile lead at the point and came away the victor with a time of 11 days, 20 hours, and 36 minutes. He lowered Bauer’s World Record by 16 hours.

In 1988, Mittleman ran a 12-hour run in Syosset, New York, on a track, and came in third with 73 miles. He also ran the 100 mile race at Shea Stadium that year, but dropped very early, at mile 16. Soon thereafter, he put a hold on his competitive running career at the young age of 37 to devote his time developing his fitness training business, “WorldUltrafit” that he founded in 1987.

Coming out of Retirement

In 1992 Mittleman, at age 41, came out of racing retirement and competed for the first time in several years by running at Metropolitan 50. In 1993, he returned and won that event. Also, that year he ran in the new Ted Corbitt 24-Hour run to honor the “father of ultrarunning.” Corbitt showed up and even ran 77 miles at the age of 73. Mittleman could still run fast and far. He placed second with 129 miles. In 1994, Mittleman became the first American ever to win the six-day race in La Rochelle, France. He covered 536 miles. In 2000, he ran across America from San Diego to New York City in 56 days, raising about $175,000 for charity.

In 1992 Mittleman, at age 41, came out of racing retirement and competed for the first time in several years by running at Metropolitan 50. In 1993, he returned and won that event. Also, that year he ran in the new Ted Corbitt 24-Hour run to honor the “father of ultrarunning.” Corbitt showed up and even ran 77 miles at the age of 73. Mittleman could still run fast and far. He placed second with 129 miles. In 1994, Mittleman became the first American ever to win the six-day race in La Rochelle, France. He covered 536 miles. In 2000, he ran across America from San Diego to New York City in 56 days, raising about $175,000 for charity.

Slow Burn

Mittleman published a book in 2002, “Slow Burn” that contained excellent advice for runners. About 2004, he moved to Palm Desert, California. In 2008, he was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. In 2010, he ran twelve marathon distance runs in twelve days to raise money for Haiti. In 2011, at the age of 60, he ran his last-known ultra, the Peanut Island 24-hour run and covered 71 miles. He ran with one of his clients who was raising money for a boy fighting cancer. In 2024, Mittleman was 73, and was living in Indio, California.

Mittleman published a book in 2002, “Slow Burn” that contained excellent advice for runners. About 2004, he moved to Palm Desert, California. In 2008, he was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. In 2010, he ran twelve marathon distance runs in twelve days to raise money for Haiti. In 2011, at the age of 60, he ran his last-known ultra, the Peanut Island 24-hour run and covered 71 miles. He ran with one of his clients who was raising money for a boy fighting cancer. In 2024, Mittleman was 73, and was living in Indio, California.

Sources:

- Stu Mittleman, Slow Burn

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), Dec 9, 1967, Sep 21, 1972, Jun 21, 1973, Jun 17, 1979

- Newsday (Melville, New York), Apr 18, 1978

- Nick Marshall, Ultra Distance Summary, 1979, 1980

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Jul 1981, Jul 1982, 1983, 1984, Jul 1986

- Daily News (New York, New York), Jun 14, 1981, Jun 14, 16. 18, 1983

- The Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey), Jun 8, 1981

- The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey), Jun 8, 1981, Jun 7, 1982, Mar 14, 1983

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), Aug 31, 1981

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), May 9, 1981

- Press and Sun Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Jun 9, 1983

- The Buffalo News (New York), Jun 10, 1984

- Hartford Courant (Connecticut), Jun 1, 1984

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), Jul 25, 1984