Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:09 — 29.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

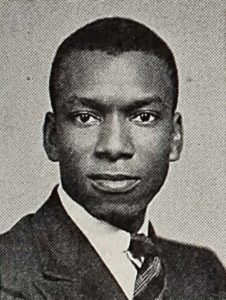

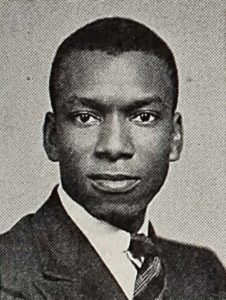

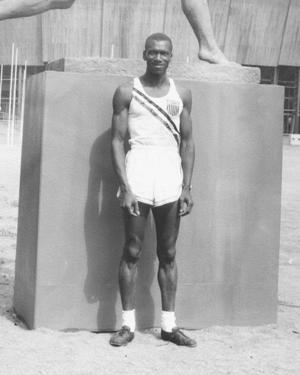

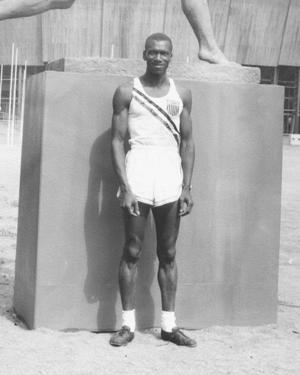

Ted Corbitt, known as “The Father of American Ultrarunning,” was from South Carolina, Cincinnati, Ohio, and New York City. Ultrarunning has existed for more the 200 years, but with the Great Depression and World War II, it went on a long hiatus in America. Because of Corbitt’s efforts, running past the marathon distance took root in the New York City area, starting in the late 1950s.

Not only was he a world-class runner, but he became a talented administrator, and race organizer that made huge contributions toward innovations to the sport, such as course measurements, that we take for granted today. All ultrarunners need to take time to learn who this man was and not let the memory of him fade. He was the first person to be inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. Because of his significance to the sport, this will be a multi-part article/episode. Visit TedCorbitt.com to learn far more about this amazing athlete and man. Also, you can read his official biography by John Chodes: Corbitt: The Story of Ted Corbitt, Long Distance Runner.

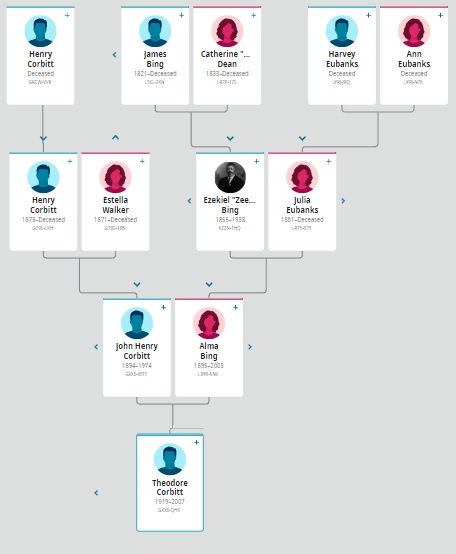

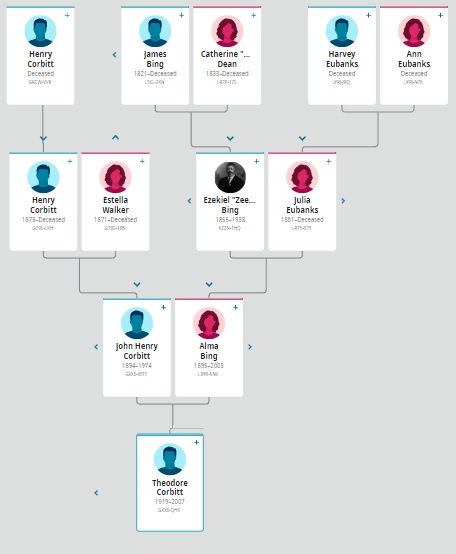

His grandfather, Deacon Zeek Bing (1855-1938) was born into slavery, also in Barnwell County. In 1860, there were at least 17,000 slaves in the county. Most of them had ancestry from Angola, Africa. Children on the cotton plantations started to work by about the age of five and by 10-12 years old did hard adult work. When freedom came after the Civil War, the hard work as freedmen to survive in South Carolina did not go away.

Ted Corbitt was the oldest child in his family. He later had two sisters, Bernice (Corbitt) Buggs (1926-2006) and Louise Estelle (Corbitt) Fairbanks (1927-2022) and two brothers, Elijah Corbitt (1928-1999), and Henry Corbitt (1924-1925) who died as an infant.

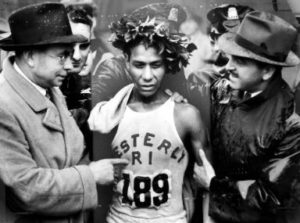

During his high school years, he saw a newsreel about the native American, Ellison “Tarzan” Myers Brown (1913-1975), who won the 1936 Boston Marathon. He marveled at the ability of anyone to run such a great distance and made a vow to himself to run Boston someday. Each year, he followed the results and put Boston Marathon articles in a scrapbook.

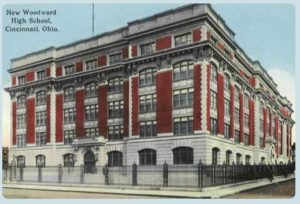

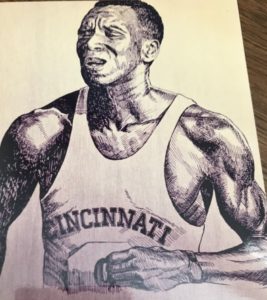

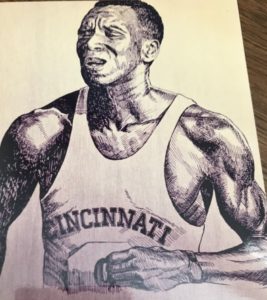

In 1938, Corbitt attended the University of Cincinnati, walking a five-mile round trip from his parents’ house each day. He joined the track team. It was unorganized; the season was short, and because of segregation, he could not run in some competitions. Corbitt was unusual in that he trained on his own during the off-season and increased in ability to run longer distances. He achieved outstanding academic success in the Teacher’s College, earning a spot on the Dean’s list and honor roll every year.

Needing more running opportunities, he joined the Drucker Athletic Club, a local A.A.U. club. He was mentioned in the newspapers running various distance races. One very competitive running event that he ran in each year, for four years, was the Six-mile Thanksgiving Run in Cincinnati. Cincinnati has been the home of this historic race since 1908. In 1939, he finished a very strong seventh with 34:37.

During his junior year, the track team was given more emphasis by the university. Oliver Mumford Nikoloff (1889-1964), who coached other sports, took over the track team and gave them real instruction. He would teach and coach at the university for 42 years. A cross-country team was also reestablished, but only competed in one race. Nikoloff supported a racially integrated team and took segregated schools off the track team’s meet schedule. After the track season, Corbitt was left on his own to continue his training. He mostly just followed his instincts and incorporated things like interval training and running up and down hills.

During his senior year in 1941-42, he became the team’s best sprinter, with a 10.1 100-yard dash and he also excelled in the 440 with a PR of 50.7. After pulling a hamstring while sprinting, his season mostly ended.

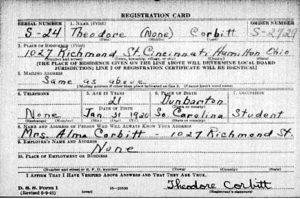

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, the United States entered World War II. Now out of college, Corbitt believed that being drafted into the service was the next phase of his life. He registered for the draft and worked in construction while he waited, and later worked at a cookie factory. He underwent a pre-induction physical and was informed that he had tuberculosis. An x-ray revealed a damaged lung. Despite feeling well and being able to carry out regular tasks, he was not enlisted in the military in 1942.

On August 7, 1943, Corbitt witnessed the legendary Swedish middle-distance runner, Gunder Hagg (1918-2004) breaking the two-mile American Record in 8:51.3 at Withrow Stadium in Cincinnati, with 2,000 spectators. Hagg held seven world records from 1500 to 5000 meters, with a mile time of 4:04.6 and was called “the world’s greatest runner.” He was on an American tour. Corbitt was in awe watching him run and was deeply affected by this amazing event. It inspired him to start training for longer distances instead of sprint distances. He ran a 9:06 two-mile time trial and prepared to compete in an A.A.U 30-kilometer national championship race, but it ended up being canceled.

In the 1943 Thanksgiving six-mile race Corbitt finished in fifth place, with 34:19. He also competed in the Ohio A.A.U Cross Country Championships. During the summer, he put on a surprising performance at an A.A.U. meet in Cincinnati. “One of the finest performances of the meet was that of Ted Corbitt, Negro 440-yard dash man for the Ninth Street YMCA. Corbitt came from far back on the last turn to nose out George Bauer. The winner’s time was 53.2.”

Corbitt made trips to New York City. He spent time in the area to see Ruth Eva Butler (1921-1989) who worked as a maid, (later as a nurse) and lived with her widowed father, who managed an apartment building. Ruth and her family had lived next door to the Corbitts in Cincinnati, but had moved to Brooklyn, New York, while Corbitt was in college. He had known Ruth since before he was 15 years old, and a relationship developed.

Corbitt had another selective service physical in the fall of 1944, and this time he passed it. He was drafted into the segregated service in November 1944 and trained to become a machine gunner. While on a weekend pass, he asked Ruth to marry him. Marriage would wait until he returned home. He was assigned to a ship in Seattle, Washington, and sailed to the South Pacific. During the summer of 1945, as he was about to disembark on the mostly secured Okinawa, news came about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Corbitt spent six months on Okinawa and could not do much running because hidden mines still existed. He was transferred to Guam in January 1946 and was discharged in September 1946.

Corbitt first returned to Cincinnati for a while and ran in a race there in November 1946. But he then made his way to Brooklyn to see Ruth. On December 16, 1946, they were married in Brooklyn. Ruth’s father, Ozzie Butler (1889-1983) lived with them in 1950, in an apartment building at 1930 Pacific Street in Brooklyn. Corbitt embarked on a career in physical therapy while also taking up part-time night classes at New York University to obtain a master’s degree.

In September 1947, Corbitt ran in the National Junior A.A.U. 25 km Championship in Milburn, New Jersey and finish 14th with 1:43:22 in a highly competitive field with 69 runners. It was witnessed by 10,000 people along the road. He listed himself as unattached from a running club, but after the race, Harry Wilson Murphy (1914-1992), a legendary marathon champion and sign painter, who finished right before him, invited him to join the New York Pioneer Club, which he did. (Murphy later founded the Prospect Park Track Club in 1970).

The New York Pioneer Club was founded in 1936, in Harlem. It was the first large-scale integrated. running organization in the world. The Pioneer Club constitution stated: “The object of this organization is to support, encourage, and advance athletics among youth of the New York Metropolitan district, regardless of Race, Color or Creed.” But with his busy life, Corbitt did not have time for serious training, usually only getting out for a short run once a week.

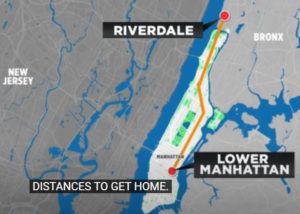

Later, in 1955, that would become much further, taking an hour and 35 minutes, about 11 miles from work to his new apartment in the Bronx at 225th and Broadway. That run was only a quarter hour longer than by subway. He said, “You have to watch yourself in traffic. You can only afford one misstep.” Over the next few years, he would be bitten by dogs several times and stopped by suspicious police over 200 times. When he arrived home, he would run up all 15 flights of stairs to his apartment. Many times he would take a 20-mile route.

Taking advantage of the additional time now finished with school, he began a rigorous training regimen for his first-ever marathon. In the absence of a coach and minimal involvement in the Pioneer Club, he took the initiative to learn how to train on his own. He read about unusual training methods published by Czech Olympic champion Emil Zatopek (1922-2000). Zatopek endorsed the idea of resistance training by running in heavy combat boots. Corbitt tried it and suffered from bruises and blisters from the boots, but persisted. By August 1950, Corbitt could run 15 miles in the crazy boots at Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. He worked up to the goal of running 30 miles (without the boots) and succeeded in early 1951. He also incorporated speed work and set a goal to run sub-3-hours at Boston.

April 1951 arrived, and he toed the start line at the Boston Marathon with 150 starters. During the early miles, he ran in about 40th place. He suffered from a stitch in his side, but pushed on, becoming dehydrated. He was tired but still passed dozens of runners. With two miles to go, he started to cramp up, causing him to shorten his stride. He finished in 15th place with 2:48:42, which was outstanding for a first-time marathoner. This was the first of his 223 marathons or ultras during his running career, and the first of his 22 Boston finishes. During the post-race interactions, Corbitt heard others talking about the upcoming Olympic Marthon Trials.

Two weeks later, Corbitt ran in a 10-mile race at Yonkers, New York against some of the best long-distance runners in the east, some who were 1952 Olympic marathon hopefuls. He placed eighth with 1:03:38. Long-distance running had certainly taken a front seat in his life. In May 1951, Yonkers was also the site of his second marathon, where he finished 13th, with 2:48:58. During that rainy race, he had to dive into a muddy ditch to avoid being hit by a car skidding toward him. He finished feeling better than he was at Boston. He became a “marathon addict” and sought to run in all of the few marathons held at the time in the northeast. Corbitt received encouragement from experienced runners, stating that he would be a great candidate for the U.S.A marathon team at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland.

Controversy boiled when Edwin John Shepard (1921-2003) of Gorham, Maine, a member of the A.A.U. long distance committee, charged “favoritism” and “disregard of rules” in the selection of Corbitt over Lafferty, citing Laffery’s marathon wins in 1951. “Corbitt should have been disqualified as a candidate, Shepard said, for failing to finish in the first ten in the nationals last year.” Shepard’s facts were wrong, and the protest failed. Corbitt was on the team.

In early July 1952, the USA Track and Field team gathered and trained for a week at Princeton, New Jersey. After flying to Finland, Corbitt was alarmed that the area was experiencing a heat wave. It was very difficult for them to train out on the public roads because of aggressive autograph hunters. “The three men trained every day, sometimes twice a day. They used several running environments: a horse track, a grassy park, rolling meadows, hiking trails through forests, and the out-and-back marathon course itself.” Corbitt was thrilled to meet Emil Zatopek, “The Prague Express” whose training program he had used.

Of the Olympics opening ceremonies, Corbitt wrote, “I have seen the opening ceremony in movies and read of them, but there is nothing like being there. There is a blast of trumpets, followed by the release of thousands of pigeons symbolizing peace. Next, a twenty-one-gun salute. All this added to the buildup of excitement. A terrific roar greeted the arrival of the final torch bearer through the marathon gate, the fabulous Paavo Nurmi sprinted around the track to light the token flame.”

The start of the marathon on July 27, 1952, was delayed because of picture taking. Zatopek, who had won gold in the 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters surprisingly was inserted into the marathon field. He had never run a marathon before. The gun went off, and they ran around the track 3 ½ times and then exited the stadium.

As he left the stadium, Corbitt felt a terrible stitch in his side. He slowed and his teammates passed him. The pain would not end. He tried to block it out but fell into 45th place by the 10-mile mark. He was still running faster than ever before. Nearing the turnaround, he could see that Zatopek had taken the lead. A favorite, Jim Peters (1918-1999) of Great Britain collapsed at the 20-mile mark.

- Ted Corbitt – The Father of American Ultrarunning – Part One

- Ted Corbitt – Part Two – 1853-1963

- Ted Corbitt – Part Three – 1964-2007

Sources:

- John Chodes, Corbitt: The Story of Ted Corbitt, Long Distance Runner

- Gary Corbitt, TedCorbitt.com

- Ancestry.com

- Familysearch.org

- Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Jun 24, Nov 18, 19, 24, Mar 1, 1939, Mar 1, May 18, Jul 19, 1940,

- The Cincinnati Post (Ohio), Jun 1, 5, Oct 30, 1942, July 26, Aug 9, 1843

- The Morning Herald

- The Millburn and Short Hills Item, Sep 25, 1947

- The Day (New London, Connecticut), Nov 11, 1950

- Mount Vernon Argus (White Plains, New York), Apr 30, 1951

- The Standard-Star (New Rochelle, New York), Apr 30, 1951

- Biddeford-Saco Journal (Biddeford, Maine), Jun 22, 1951

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 20, 1941, Jul 1, 1952

- “History of 20th Century Running in Greater Cincinnati” https://gcincyrunhistory.blogspot.com/2016/

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Apr 20, 1952

- The Daily Times (Mamaroneck, New York), May 19, 1952

- The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), June 30, 1952

- Portland Press Herald (Maine), Jul 3, 1952

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Jul 16, 1952