Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:43 — 39.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

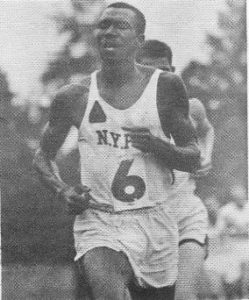

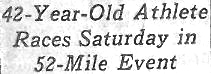

After Ted Corbitt’s disappointing 1952 Olympic marathon, he was determined to continue running. (Read Part One). His key takeaway was that he had to elevate his performance by running more often and covering greater distances. But as he continued to push his training, he experienced a series of chronic muscle strains for the next year.

After Ted Corbitt’s disappointing 1952 Olympic marathon, he was determined to continue running. (Read Part One). His key takeaway was that he had to elevate his performance by running more often and covering greater distances. But as he continued to push his training, he experienced a series of chronic muscle strains for the next year.

Corbitt was focused on the marathon distance and continued to finish high each year at Boston. He believed that success would require training every day, reaching at least 100 miles per week. His perseverance finally paid off in January 1954, when he emerged victorious in a marathon held in Philadelphia, completing it in 2:36:08. He won again, at the 1954 Yonkers Marathon, considered the national championship, with a time of 2:46:13. He had proven that his 1952 Olympic selection was justified. In 1955, he made the team for the Pan American team in Mexico City but was cut from the team became of lack of funds. It bothered him that some newspapers listed him as a non-finisher in the race. He never started it. Throughout his long running career, he never had a “did not finish (DNF).”

| Learn about the rich and long history of ultrarunning. There are now ten books available in the Ultrarunning History series on Amazon Learn More |

London To Brighton

Ultra-distance races essentially disappeared during the World War II era. In the late 1950s, the modern era of American ultrarunning gave birth. This was largely because of the efforts of the Road Runner Club of America (RRCA) established in 1958, and also because of the efforts of Corbitt.

England took the lead in the 1950s to reestablish ultras, and specifically the 50-miler. The London to Brighton 52-miler began as an official running race in 1951 with 47 starters. It had been a standard point-to-point challenge for both walkers and runners since the first running race held in 1897. Heel and Toe walking races were held for many years on the route during the first half of the twentieth century. In 1951, the London to Brighton running race was established by Ernest Herbert Neville (1883-1972) and the Surbiton Town Sports Club. It would eventually be considered the de facto world championship 50-mile race for several decades.

The Road Runners Club (RRC)

By 1953, London to Brighton got the attention of leading long distances runners from other areas of the world, especially among ultrarunners in South Africa who had been running the Comrades Marathon (54 miles). London to Brighton became the race that the best ultrarunners in the world wanted to compete in. The RRC was an amazing success and the number of road races in Britain tripled in just a few years.

America was much slower to bring ultrarunning back from its disappearance during the war years. It first needed to go through England. Ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy, wrote, “The London to Brighton race was to be a major catalyst in the development of the North American ultrarunning.” Amateur distance-running athletes who grew up running in high school and college looked to the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) to provide races, but by the late 1950s it became clear that the organization wasn’t really interested in putting on many races, especially races beyond six miles.

The Road Running Club of America

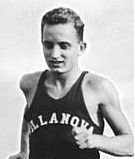

Harrison Browning Ross (1924-1998) was an important person in reestablishing road ultrarunning in America. In high school, he was a New Jersey State Champion. While attending Villanova University in 1948, he won the NCAA steeplechase championship. In 1951, he won the gold medal in the 1500 meters at the Pan American Games. He also competed in the 1952 Olympics held in Helsinki.

The Road Running Club of America

When Ross competed in England, he joined the Road Running Club and was impressed with the way it had brought new life into the sport there. Running historian, photographer, and Corbitt’s future biographer, John J. Chodes (1939-) wrote, “The RRC of England promoted the ‘spreading of the gospel’ to the other countries. Ross became a zealous missionary.” There were only nine marathons in North America, with only about 300 Americans taking part.

On February 22, 1958, under Ross’ leadership, a small group met at Paramount Hotel, in New York City, to develop the structure for a RRCA and how it would work with local chapters. Some people were concerned that the AAU would oppose the idea, but the founders were careful to work within the bylaws of the AAU, which allowed clubs to be formed within the AAU and club events could be held. The idea proposed that runners would join the AAU and then join the RRC so that they could run RRC races and not risk losing their amateur status. The first local chapter was established in Philadelphia, with Ross as president.

Harry Berkowitz (1940-2008) one of the RRCA founders at that first meeting, later wrote, “Ross had the foresight to establish an organization to get around the AAU bureaucracy and allow runners to organize races that they wanted to run.” Ross’ vision was to provide running opportunities for as many people as possible and he wanted those people to be involved in the organizing of events, not relying on the AAU to do so. This vision paved the way for today’s ultramarathons to be organized by local clubs and runners. Ultrarunning pioneer, Tom Osler (1940-2023) said, “Once Browning started the RRCA, the national mechanism was in place for running to grow by millions of runners. All that was necessary was to expand the size of the fields.”

The New York Road Runners Club

Local RRCs were organized. John Sterner (1922-1980) of the New York Pioneer Club was at that historic RRC organizational meeting. He worked with the Pioneer Club members and asked Corbitt if he would be the president of the New York Road Runners Club (NYRRC). (The original name was: Road Runners Club, New York Association). At first, he was resistant about getting involved in administration, but as the New York runners refused to join the RRCA, Corbitt agreed to be the first president of the NYRRC. In April 1958, the New York Road Running Club (NYRRC) was founded by Sterner with 29 members. Ted Corbitt was appointed president, Joe Kleinerman (1912-2003) vice president, and John Sterner as secretary. It would be the most influential organization in reestablishing ultramarathons in America.

The Cherry Tree Marathon and Ultra

Soon, there were six chapters of the RRCA. Races started to be organized, including national championships for 10 miles, 12 miles, and a fixed time race of one hour. On February 22, 1959, the Cherry Tree Marathon was originated by Aldo Maxim Scandurra (1916-1999) of the Millrose AA, and a founding member of the NYRRC. Sterner proposed that the NYRRC sponsor the race, and they agreed.

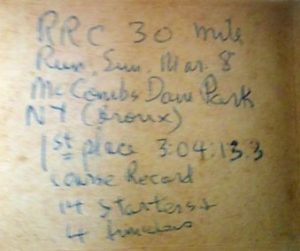

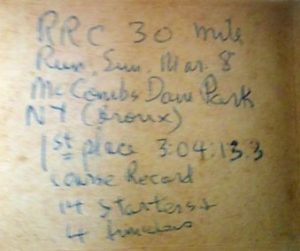

Earlier, in 1958, Michael Joseph O’Hara (1913-1998) age 45, a Navy veteran of 85 marathons, ran a 30-mile version of the Cherry Tree Marathon course in 3:33:01. It is believed that a 30-mile race was also held in MaCombs Dam Park back in 1955, where O’Hara finished second in 3:37:15. In 1962, O’Hara would become the first American to finish 100 marathons.

Corbitt ran the 30-miler, and won with 3:04:13, among four finishers. This was one of the earliest modern-era (post WWII) road ultras held in America. (A three-man 100-mile out and back road running race was held in 1952, between Salem and Portland, Oregon. Also, The Padre Island 110-miler on dirt started in 1953, in Texas.)

At the 1958 Boston Marathon, Corbitt experienced a very unusual disqualification. At a pre-race medical check, his heart rate was considered high by doctors who did not understand the pre-race excitement and stress experienced by elite runners. Two others were also disqualified. Corbitt ran anyway and finished in unofficially 6th with 2:43:47. The other two finished in 7th and 9th place. At the 1958 Shanahan Marathon in Philadelphia, he set his lifetime personal best of 2:26:44, the third fastest marathon by an American at that time.

The Ultramarathon

In Corbitt’s mind, establishing a 30-mile race was the first step toward establishing a 50-miler. He dreamed of breaking the American 50-mile record which was thought to be 6:13:58. (The American 50-mile record was actually 6:18:00, set by Dennis Donovan (1858-1882) of Natick, Massachusetts, in 1880 on a track. On the road, Johnny Salo (1893-1931) ran 50 miles in 6:34:55 in 1929. Both were professional runners).

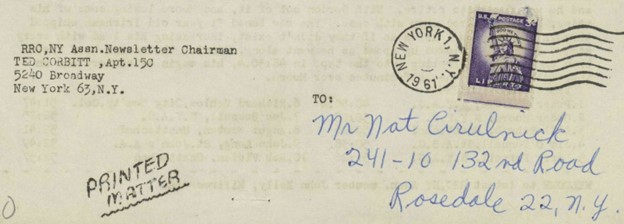

During the Summer of 1959, Corbitt started publishing a Road Runners Club, New York Association Newsletter that came out quarterly. In his fall 1959 issue, he suggested holding up to three races each year of 30-50 miles. He called them “ultra-long distance races.” But ultra races were put on the shelf for a few years. The 30-miler taught Corbitt that racing past the marathon mark was possible, but to reach 50 miles would require much more work because near the end of the 30-mile race his legs at stiffened and he became dehydrated because he did not take in fluids as he ran. Still, 50 miles remained a goal.

In about 1959, Corbitt coined the turn “ultramarathon” for a race more than the marathon distance. The term had been used before in isolation, to help newspaper readers understand that an extra-long endurance feat was taking place. The Redwood Indian Marathon (480 miles), held in 1927, in California, was referred to in a headline as an “Ultra Marathon.” In 1977, Jim Shapiro used the term in a widely published article about ultrarunners. It then became a mainstream term.

The Belt Buckle

Most ultrarunners of today have been told that the Western States 100 started the belt-buckle tradition and awarded the first ultramarathon buckle in 1977. They certainly instilled the long-lasting tradition in the sport, but they did not award the first ultra buckle. Buckles had a long tradition as an award in sports. In the 1920s buckles were awarded in amateur boxing matches. In 1923, in Sacramento, California, they were awarded to the first six runners who finished a cross-city race of two miles. During the decades to come, buckles were awarded in football, wrestling, swimming, track and field, rodeo, endurance horse riding, and even bowling.

In 1959, Corbitt and the NYRRC awarded the first ultramarathon belt buckle to the top three finishers of the Cherry Tree 30-mile Marathon, more than 18 years before the first buckle would be awarded by the Western States Endurance Run.

Early RRCA Years

In 1960, Corbitt served as the national president of the RRCA for a year. He had a challenging year as president of the RRCA. The AAU viewed the RRCA as an emerging threat, especially the New York chapter. The AAU flexed their muscles and at first refused to accept the RRCA as a participating member of the AAU and told the RRCA to stop organizing races. They wanted the RRCA to just be a social running club. But with Corbitt’s leadership and influence, the issue was resolved. The RRCA pushed on, and eventually the AAU sanctioned RRCA races.

Many more RRCA races started to be held. For example, before the Midwest RRC was established, Chicago had 3-4 distance races per year, but by 1961 there were about 20 per year in the Midwest RRC.

1962 London to Brighton

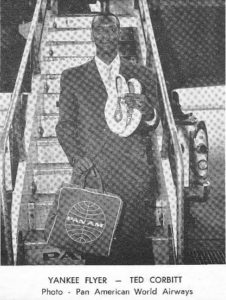

Corbitt continued to compete well in many marathons. By the end of 1961, he was approaching 50 career marathon finishes. Back in 1956, when he made a business trip to Europe, he often ran past the marathon mark in training. While there, he had thoughts of running London to Brighton, but he did not. After winning the Shanahan Marathon in January, 1962, he set his sights on running London to Brighton in 1963. But then, Browning Ross approached him and suggested that he should plan to run the 1962 London to Brighton, and that he would help raise funds for the plane fare.

In Browning’s January issue of The Long Distance Log, he put Corbitt on the cover. In the next issue, he wrote, “The 12th Annual Open Road Running Race from London to Brighton, England is one of the world’s classic races. This year’s 54-miler will be held on September 30, 1962. I would like to propose that a fund be started to send Ted Corbitt over, in quest of the ‘Arthur Newton Cup.’ I can think of no American runner more deserving of such a trip than the veteran New York Pioneer Club marathoner. Ted feels that with a year’s preparation, that he can well represent the United States in this great race. $300 would be the minimum plane fare and we feel sure that our friends in the British RRC would accommodate Ted during his visit.”

Reaction to this fund-raising effort was positive. William “Bill” Wiklund (1907-1980), of New Jersey, who had coached Johnny Salo (1893-1931) to his 1929 win in the “Bunion Derby” race across America, gave high praise to Corbitt. “After having witnessed a great deal of this longer distance type of running, and also all of Ted’s performances in the past ten years, I feel certain that he is the ideal choice for this race.”

By mid-June, Corbitt had lost eight weeks of training due to illness, injuries, and attending school. In May he had tried to run 52 miles but stopped, discouraged, at 32 miles. During the summer, his training improved. The fund-raising effort was successful. At the Milk Run, Browning presented Corbitt with the funds for his plane trip. Corbitt had been doing some long training runs to get ready, including back-to-back 50-miler on Labor Day weekend. On September 16th, about two weeks before the race, he ran a 42-mile training run in 5:04. He wrote, “Best solo effort around Manhattan.” It gave him confidence that he was ready, and he began to taper. “I ended training with my legs almost pain free, in contrast to the problems at the start of intensive training.”

The British press knew that Corbitt was going to compete in London to Brighton and mentioned him in many newspapers. After arriving in England on September 24th, Corbitt contacted the RRC for help in finding handlers to ride a bicycle along with him during the race. Legendary 83-year-old RRC founder, Ernest Neville visited him, welcomed him to London, and gave him advice about the course.

The Race

Corbitt met a few elite runners who had run well in the recent Comrades Marathon in South Africa. Checking in consisted of just receiving bib numbers for the front and back of his shirts. He wrote, “There was no pre-race physical examination. Instead, the RRC had a committee to check entries. They rejected five entries this year because they found that these men had not trained enough to tackle this event. A physician and an ambulance were in attendance during the race.”

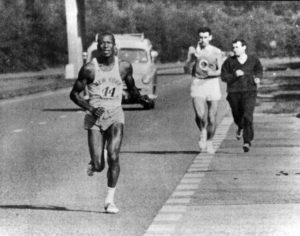

The race started on September 29, 1962, when Big Ben tolled at 7 a.m., with 46 runners. Corbitt started mid-pack but then accelerated to run with the leaders. At ten miles, he was just two minutes behind the leader. At 20 miles, he was in fourth and he reached the marathon mark at 2:45. He took his first refreshments at mile 23. They always ran on the left side of the road with traffic. Corbitt wrote, “I decided to stay as close to 10 m.p.h. as I could for as long as possible.” He started in a Pioneer Club sweatshirt but later discarded that, revealing a “American RRC” shirt given to him by the NYRRC.

Each runner had a cyclist handler riding near them. The cyclist could scout out the competition. At the “Valley of Shattered Dreams” Corbitt’s cyclist urged him on, but Corbitt’s quads from screaming and wouldn’t let him run faster. Dale Hill appeared at mile 45, the biggest hill on the course. At the top, mile 46.5, he was still in fourth, about four minutes behind the leader. On the downhill, Corbitt’s cyclist yelled, “Show me what an American can do! You call that running? My five-year-old sister can run faster than that!” Corbitt tried hard, but just couldn’t catch the runner ahead. All the leaders struggled for the last six miles. Corbitt finished in fourth with 5:53:27. He set the record for the fastest “newcomer” and was determined to return and run faster. Brighton’s mayor, William Button, presented him with the fourth-place plaque and a trophy for the fastest newcomer.

Chodes wrote, “Between finishing and the awards ceremony, Ted underwent an amazing transformation. Instead of a shattered runner whose last thoughts were to endure this torture again, he was suddenly filled with renewed enthusiasm. This time, the course mastered him. The next time he would be running to conquer the Brighton Road.” He extended his stay in Europe to take an advance massage class. The day after the race, he could barely lift his feet. The next day, he walked a very slow quarter mile. After four days, he could finally cover 2.5 miles in 30 minutes.

Ultramarthons Begin in the Eastern United States

Corbitt’s outstanding performance on the world stage at London to Brighton caused some enthusiasm among Americans to compete in distances greater than the marathon distance. They did not know it at the time, but this would launch the modern era of ultrarunning in America. It was time for more Americans, besides Corbitt, to venture into ultra distance.

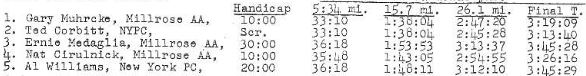

Aldo Scandurra, of the Metropolitan AAU Long Distance Committee, took up the baton and started a program of ultramarathons 30-44 miles to be held regularly. Corbitt hoped these races would generate a core of American runners who could compete at a future London to Brighton once they were ready. “These will be invitational races. To receive an invitation, a runner must have proven his ability by having run a great many marathons or he must be approved by the chairman (Scandurra).” Several of the races were handicapped races, where starters were given head-start minutes credit compared to Corbitt, who had no advantage.

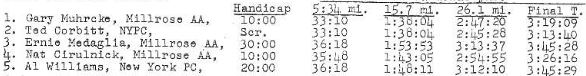

The first handicapped race in this historic ultra series was a 30-miler held at Van Cortlandt Park in The Bronx. Corbitt finished in third place, in 3:22:32, but with the fastest time. The next AAU 30 miler was held three weeks later on Jan 20, 1963, again in the Bronx. It also was a handicapped race. Corbitt again had the fastest time with 3:13:40. These road ultras were organized without aid stations. Instead, handlers drove along or rode bicycles.

In March 1963 a 33-mile race with handicaps was held in Bethesda, Maryland, where Corbitt finished in second place with 3:57:00. During the hot July summer, a 35-miler was held again in The Bronx. The road was so hot that Corbitt’s shoes melted and fell apart. He received a new pair from his nine-year-old son, Gary, as he passed by his house. He won in 4:34:45. He had no intention to run London to Brighton in 1963 but headed up a fund for donations to send someone to England. Others wanted to go, but as it came closer, he discouraged that idea, because he felt that they were not ready, “would get murdered,” and needed another year to train. Two more “developmental” ultras were held in 1963, a 44-miler in Alexandia, Virginia, and a 30-miler that started at Yankee Stadium. Corbitt won both of them. These races were a successful beginning, but something else caused ultrarunning to explode in 1963.

The 1963 50-mile Frenzy

Corbitt did not take part in this 1963 50-mile frenzy and concentrating on more serious races, but with the ultras being established in the East, and with positive public awareness that venturing past a marathon was possible, the infancy of modern-American ultrarunning was ready to take off. A new generation of ultrarunners would enter the sport in the New York City-Philadelphia area that would lay the foundation for the modern era of the sport.

- Ted Corbitt – The Father of American Ultrarunning – Part One

- Ted Corbitt – Part Two – 1853-1963

- Ted Corbitt – Part Three – 1964-2007

Sources:

- Jack Heath, Browning Ross: Father of American Distance Running

- John Chodes, Corbitt: The Story of Ted Corbitt, Long Distance Runner

- tedcorbitt.com

- “History of Road Runners Club of America”

- Andy Milroy, North American Ultrarunning: A History

- Andy Milroy, The Long Distance Record Book

- Abilene Reporter-News (Texas), Apr 12, 1927

- Long Distance Log March 1959, January, February, March, October, December 1962, March 1963

- RRC-NYA Newsletter, Summer 1959, Fall 1959, Spring, Winter, 1960, Fall, 1962

- The Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Aug 30, Sep 11, 1952

- The Observer (London, England), Dec 14, 1952

- Road Runners News Letter (England), Dec, 1952

- The Gazette, (Montreal), Sep 7, 1954

- Daily News, (New York), Oct 20, 1957

- The Corpus Christi Caller-Timer, Feb 18, 1963

- “The History of the London to Brighton Race,” Ultramarathon World, 1998

- Timothy Noakes, Lore of Running

- Leonard T. Olsen, Masters Track and Field: A History

- The New York Times (New York), Sep 23, 1962

- The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio), Aug 27, 1956