Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:33 — 45.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

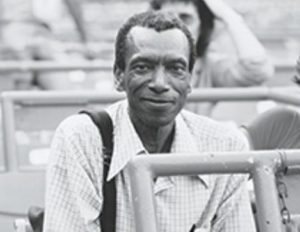

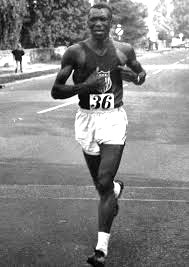

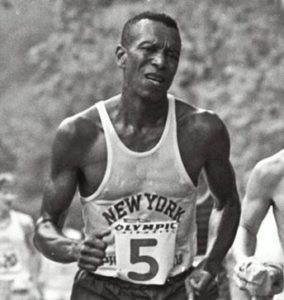

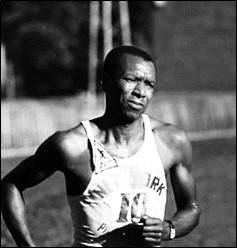

For most elite ultrarunners, as they reach their mid-40s, their competitive years are mostly behind them. But for Ted Corbitt, his best years were still ahead of him, as he would become a national champion and set multiple American ultrarunning records. Read/Listen to Part 1 and Part 2 of Corbitt’s amazing history as he became “The Father of American Ultrarunning.”

For most elite ultrarunners, as they reach their mid-40s, their competitive years are mostly behind them. But for Ted Corbitt, his best years were still ahead of him, as he would become a national champion and set multiple American ultrarunning records. Read/Listen to Part 1 and Part 2 of Corbitt’s amazing history as he became “The Father of American Ultrarunning.”

Perhaps Corbitt’s most notable achievements in the sport of long-distance running was his groundbreaking work in course measurements. He said, “My initiating the accurate course measurement program in the USA is easily the most important thing that I did in the long-distance running scene.” He understood that “for the sport long-distance running to gain legitimacy, a system was needed to verify performances, records, and ensure that courses were consistently measured in the correct manner.”

| Learn about the rich and long history of ultrarunning. There are now ten books available in the Ultrarunning History series on Amazon Learn More |

Course Measurement Standards

Mistakes were made at times. In October 1879, a couple weeks after the Fifth Astley Belt race held in Madison Square Garden, won by Charles Rowell (1852-1909) of England with 530 miles, the track was remeasured for another race and was discovered to be several feet short per lap which meant that Rowell actually instead covered 524 miles. The controversy resulted in a lawsuit because the error affected the distribution of enormous winnings earned by the runners. After that debacle, race managers were much more careful about certifying their tracks.

In the 20th century, ultrarunning returned to road courses. With the introduction of the automobile, odometers were typically used. But those devices were rarely calibrated accurately as auto manufacturers liked to have them register more miles than actually traveled. Off-road course measurement was even more difficult. In 1959, a five-mile cross country course was used in the Bronx, New York. A careful remeasurement after the race discovered that the course was short by 490 yards.

Another important example: As the famed Western States Trail was used by the horse endurance race, The Tevis Cup, in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, and for the early years of the Western States 100 foot race, it later was discovered in the 1980s the course was not even close to 100 miles, it was no more than 89 miles, more than 10% short. It wasn’t initially a 100-mile race.

As Corbitt went to England in the early 1960s to compete in London to Brighton, he became acquainted with John Jewell (1912-2001), a founding member of the Road Runners Club in England. In 1961, Jewell wrote a paper describing the process of road race course measurement in England. He refined a method of using calibrated bicycle wheels for measurement. Jewell measured the London to Brighton course that Corbitt competed on.

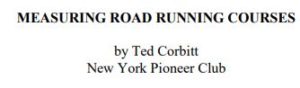

Corbitt was convinced that a method of accurate course measurement was needed for America’s long-distance races. He pointed out, “The U.S. has sent marathoners and walkers to the Olympic Games who thought they were in a certain time range, but who in reality were several minutes slower on full length courses. This is unnecessary since it is possible to measure courses accurately.” He exported many of Jewell’s ideas, did his own research, and published a historic 29-page booklet in 1964, “Measuring Road Running Courses.” He evaluated all the typical methods of measuring courses and concluded that the best method was to use a calibrated cycle wheel, which was extremely accurate and could be used rapidly.

The concept was simple, to use a counter similar to the ones found on a surveyor’s wheel to keep track of the rotations of a bicycle wheel. He included details of how to construct a home-made measuring wheel. Corbitt made it an immediate goal for the NYRRC to get all their courses checked, measure, and certified.

In 1970, Alan Jones, an IBM computer engineer, inspired by Corbitt, made the wheel measuring process easier when he invented the Jones Counter, which Corbitt endorsed and distributed to many races.

Corbitt’s efforts for accurate road course measurement, led to the formation of AAU’s National Standards Committee, which later became the Road Running Technical Council (RRTC). He established America’s first course certification program and served as the country’s chief course certifier from 1964 to 1984. In 2015, the RRTC established the Ted Corbitt Award, “given to a person who has demonstrated a superior level of skill, consistency and competency in course measurement and certification over a sustained, extended period of years.”

1964-1965

At London to Brighton, Corbitt finished in second place, only 58 seconds behind the winner, Bernard Gomersall (1932-2022) of England. The other Americans fared well. The Millrose AA team narrowly lost the team title to the Tipton Harriers. Thanks to Corbitt, Americans were finally competitive in international ultrarunning.

Corbitt wrote encouraging words for those considering trying to run ultramarathons. “The Millrose men found the experience of becoming 50-milers not as difficult as expected once the soul-killing summer training was finished. The message is, that a trained marathoner can race up to 30-40 miles with no added training. With a little added training you can run 50 miles. If you want to run these distances very fast, then much added special training is needed unless you are a 2:30 marathoner.”

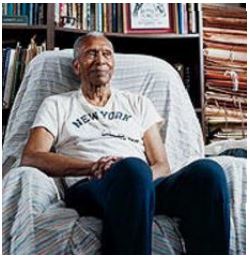

Tom Osler, America’s 50-mile champion later recalled, “My most memorable meeting with Ted came when my wife Kathy and I visited him in his apartment in the Bronx. We sat in his living room as he described his training for upcoming ultra races. He frequently ran from his apartment to Manhattan, then circled the entire island of Manhattan and returned home, a distance of almost 35 miles. He would carry change with him so that he could ride the subway in case of difficulty. Sometimes he did two laps – nearly 70 miles!”

At the 1965 London to Brighton, he again placed second to the Comrades champion, Gomersall, in another close race. Gomersall was arguably the greatest ultrarunner in the world that year. Three other American runners also finished. His loss was a disappointment, and he later learned that if he had pushed hard one more time near the finish, that Gomersall would have conceded the victory to him.

The First AAU 50 Mile National Championship

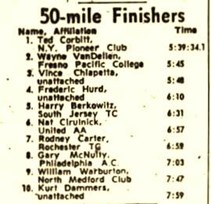

Thanks to the efforts of Aldo Scandurra and Corbitt, the AAU was convinced to recognize a national 50-mile championship to be held in 1966. The American record for 50 miles was not known at the time. It was held by a professional, Dennis Donovan (1858-1882) of Natick, Massachusetts, who ran the distance in 6:18:00 in 1880, in Providence, Rhode Island. The amateur record was 6:46:10, set in 1935 by Hugo Kauppinen (1892-1969), of Brooklyn, New York, during a Metropolitan 50-mile run on Staten Island. The 50-mile track world record was held by Gerald Walsh of South Africa, who ran 50 miles in 5:16:07 in England, in 1957. Tom Richards, of England, ran a 50-mile road split of 5:12:37 during the 1955 London to Brighton. The International Amateur Athletics Federation still did not recognize the 50-mile distance and didn’t keep records on it.

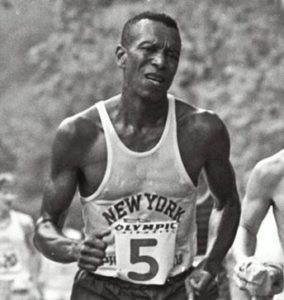

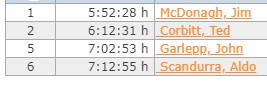

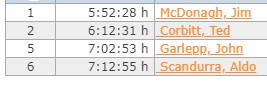

The first US National 50 Miler was held on July 17, 1966, on a road course on Staten Island, New York. Corbitt planned to win the race, but in the ultra races held in New York during the first few months of 1966, he lost some races to his new main competitor, Jim McDonagh (1924-2008). He was born in Ireland and came to the U.S. in 1952. In 1965, he dreamed of qualifying for the 1966 London to Brighton team and used the 1965 and 1966 New York City ultras to build up his abilities.

New York was in a heat wave leading up to the 50-mile championship race day. As Corbitt was packing his bag for the race, he noticed that the heat had melted the glue in his running shoes so that the sole came loose. He grabbed an old pair of leather shoes and hoped for the best.

The course was on a four-mile loop around Clove Lakes Park. Right after the starting gun, Corbitt and McDonagh separated from the others. By mile 15 it was already hot, at 80 degrees. Corbitt started developing blisters because of the old shoes, but he still hit the marathon mark at 2:49. He was still in front at mile 40, but only a few yards ahead of McDonagh.

The 1966 Walton-on-Thames 50-Miler

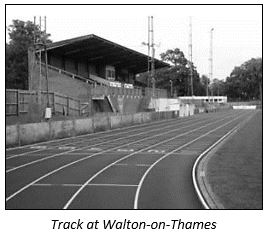

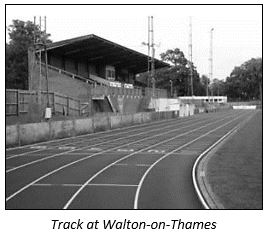

After London to Brighton, Corbitt stayed in England because he had been invited to run in a 50-mile invitational track race on October 15, 1966, at Walton-on-Thames, with 13 starters. Because of overnight rain, turn one was under water and the backstretch was very slippery. Corbitt reported “The runners splashed and skidded through this for 29 miles by which time the grounds-keeper and volunteers had used brooms and giant foam rubber sponges to clear the water away. No one attempted to run the race in spikes.”

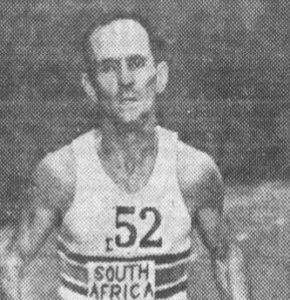

The runners were on world record pace from start to finish. South African, Tommy Malone (1938-2019), started out clocking sub-six-minute-mile pace. The leaders reached twenty-five miles in about 2:30. Corbitt said, “By this time all pursuers were in various stages of decline, each having retreated into his own private fight with fatigue.” Corbitt hung in about tenth place for the first half of the race and then moved up.

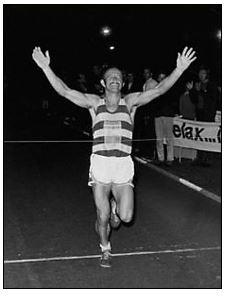

Alan C. Phillips (1929-2019) age 37, a virtually unknown runner from England, eventually went into the lead and observers believed that he wouldn’t last. He did hold on and broke the 50-mile track world record with 5:12:39. Corbitt placed 5th, with 5:54:15. That year, Corbitt also became the second runner in history to achieve the milestone of finishing 100 marathons.

The 1968 American 50-Mile National Championship

The 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100 Mile Track Race

The RRC invitational race was organized at Walton-on-Thames in England to try to break the recognized 100-mile track world record that stood at 12:46:34, set by Wally Hayward in 1953. (Dave Box’s 12:40:48 mark set in 1968 was unfairly not recognized by the British RRC).

Corbitt first ran London to Brighton, finishing in second place. He recovered by doing runs on the grass. To concentrate on his 100-mile training, he avoided people. But being alone aggravated a depression issue. To help, he went sight-seeing. He took a trip to Sweden at the invitation of runner Soren Winge, one of Sweden’s top cross-country runners. Recovered, he could run 20-mile training days again.

With twelve days to go, Corbitt returned to London. “Once there, the reality of the 100-miler brought back all the depression and negativism. He became so homesick for his family that he was seriously tempted to take the next plane home.” But he stuck with it and ran a 45-mile park-hopping training run.

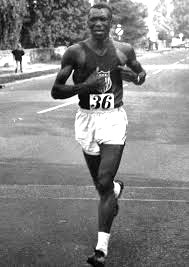

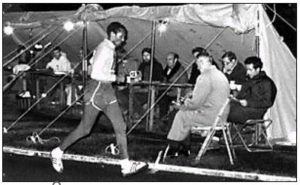

At the midnight start, Gordon Bentley (1938-) of England, moved directly into the lead unchallenged with a sub-seven-minute mile pace. The rest of the runners quickly broke up into several bunches. But by 50 kilometers, he slowly faded, and the race turned out to be a contest between the world record holder, Box, of South Africa, and John “Ghost Runner” Tarrant (1942-1975).

Corbitt reached 50 miles in 6:13:22 feeling good, hoping that Tarrant and Box would annihilate each other. Others dropped out and only nine continued. Corbitt said, “Somewhere along the way I was aware that I was slowing up. I had no state of breathlessness at any point. I did almost step on the curb maybe a couple dozen times, but this was because of a loss of attention. There was no problem with dizziness or discomfort. After a while. I sort of lost interest in looking at the blackboard. It was too much trouble trying to focus on the figures. Sometimes when I did want to check the board, to see if others were catching up, it would take two or three laps for the figures to register.” Corbitt’s 100 km split of 8:19:32 was a new American 100 km Record, beating an 1882 track mark of 8:40:00 set by John Hughes of New York City.

Box held the lead for several miles, but by mile 75 he cracked completely. Tarrant pushed ahead. Corbitt also experienced exhaustion around that point. He knew he couldn’t quit. Like Box, he had traveled too far to take an easy way out.

1970 AAU 50 Mile National Championship

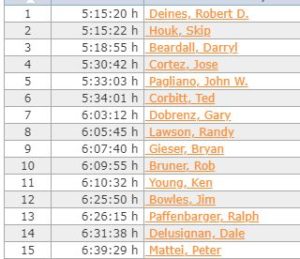

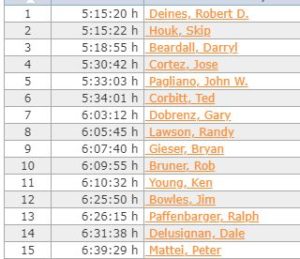

The interest in American ultrarunning continued to spread, thanks to Corbitt. A remarkable shift to the west was noticed in 1970 when the AAU 50 Mile National Championship was held in Rocklin, California. An astonishing 47 runners participated, with only four from the East, including Corbitt. He described it as “the greatest ambush since Custer’s Last Stand.” He reported, “The western aces all unloaded tremendous personal bests at 50 miles, while the easterners all came up with sub-standard performances. The Californians took the first five places.” Robert “Bob” Dale Deines (1947-), of Los Angeles, California, broke the American 50-mile record with 5:15:20. Corbitt, at age 51, finished sixth with 5:34:01, setting an age-group record that still stands today. He was beat by 18-year-old Jose Cortez (1951-) who would break Corbitt’s American 100-mile record the next year.

Corbitt wrote in his newsletter, “The east has failed to attract enough new blood onto the ultramarathon scene to meet the surging western challenge. The westerner’s next attack will be on the famed Brighton Road in England. Will the easterners who have talked of combat at 50 miles , now come into the active ultramarathon ranks, or will they yield to the western challenge in silence? The westerners have learned the obvious lesson that the 50 miler is not to be feared, but is a reasonable challenge for a trained marathoner.” There were several future Western States 100 finishers in the field that year.

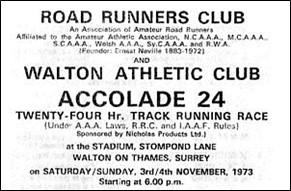

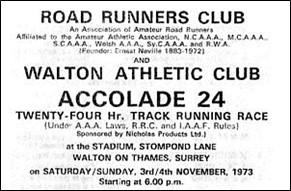

1973 Walton-on-Thames 24 Hour Race

Corbitt knew he was nearing the end of his competitive running career. But he felt he had to run this race because this would probably be his last chance to run in such an ultimate challenge. He had four months to prepare and quickly increased his mileage from 65 to 220 miles per week. He ran 20 miles to work and 20 miles home each day. But the strain was too huge, and he soon had terrible shin-splints. Still, he ran 828 miles in July, 816 in August, 740 in September, and 696 in October. Ten days before the race, he ran 101 miles in 22 hours. It went very well, and he never felt tired. He was ready.

His pre-race bio read: “Ted Corbitt (aged 53), a respected physiotherapist in New York, added an international flavour to the proceedings. He pioneered ultra distance running in the USA, being a founder of the Road Runners Club of America based on the model established by the RRC in the UK. He is recorded as having completed 171 ultra distance & marathons since 1951. He had represented the USA in the Helsinki Olympics over the marathon distance. In terms of experience, Ted was possibly the best equipped.”

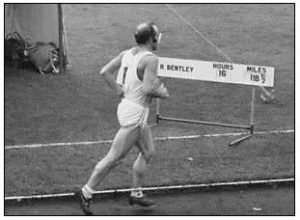

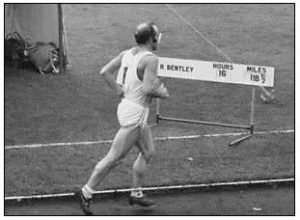

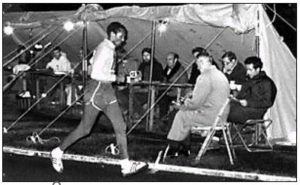

Gordon Bentley shot into the lead at 6:15-mile pace followed by his brother, Ron Bentley (1930-2019). Corbitt was content to run near the rear. After three hours, Gordon Bentley had nearly reached 25 miles, and Corbitt was two miles back. During the fourth hour, one runner threw up repeatedly, and another was seen badly limping. Corbitt stopped for a meal of a hard-boiled egg, and a cup of orange, and pineapple juice.

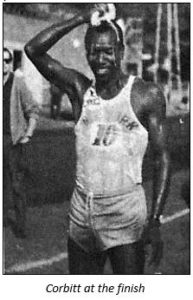

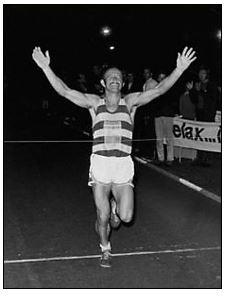

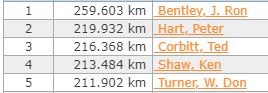

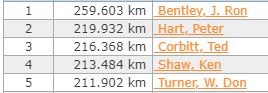

The remaining battle was for second place. Corbitt had held it for 13 hours but with 30 minutes to go, Peter Hart (1938-) was within two laps of him. “The track was a madhouse. Fans and handlers clogged the track, making an obstacle course for the runners.” Corbitt’s crew pled with him to go faster, but it was useless. He had nothing left and with 20 minutes to go, Hart passed Corbitt. Then the gun was fired, and the nightmare was over for Corbitt. Bentley reached 161.3 miles, a new world track 24-hour record. Hart reached 136.4 miles, and Corbitt, 134.6. Eleven out of the fifteen starters remained at the end.

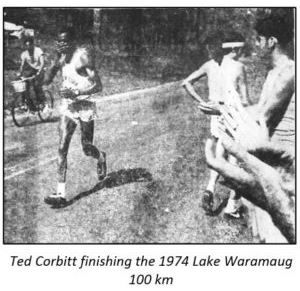

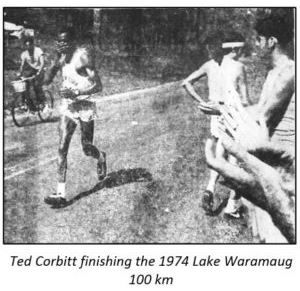

The 1974 Lake Waramaug 100 km

Corbitt said, “It was a great race. The course is beautiful, the traffic minimal. It is a moderately hard course, and I hope we can have the race every year.” He admitted that he was only in “fair condition,” and hoped to train harder for future races. The Lake Waramaug 100K became America’s de facto 100 km national championship for many years.

Historian Andy Milroy wrote, “This race marked the end of a proud era. People didn’t realize it at the time, but Waramaug in 1974 represented the true passing of a torch from one generation to the next. For Ted Corbitt, the most recognizable figure in American ultramarathoning since the 1950s, it was his last hurrah. Shortly thereafter, he was beset by nagging injuries. After two decades of elite performances, he was never again a competitive threat in these events, and soon had to give them up altogether.”

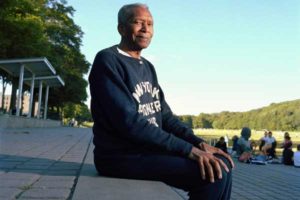

Later Years

In 2001, at the age of 82, he walked 303 miles in a six-day race held on Wards Island in New York City. He wished he would have tried that race when he was young to join the few who had accomplished 600+ miles.

In 2004, he was the first inductee into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. In 2005, he received a lifetime Achievement Award as Runner’s World Heroes of Running.

In his last public speech in November 2007, he said, “I became addicted to running long, long distance runs, and inspired others to do it better. In addition to training extensive mileage, I spent years doing administrative stuff in the background to help our sport survive and grow.”

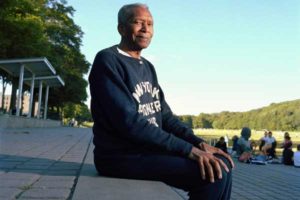

Ted Corbitt passed away on December 12, 2007 at the age of 88. USA Track and Field’s “Men’s Ultra Runner of the Year” is named after him. In 2014, 228th Street at Broadway in New York City was named Ted Corbitt Way. This is near the home that he lived in for many years. Ted Corbitt was truly the father of American ultrarunning. He is missed, but not forgotten. He was America’s ultrarunning national champion and at one time held the American records for 50 miles, 100 km, and 100 miles.

- Ted Corbitt – The Father of American Ultrarunning – Part One

- Ted Corbitt – Part Two – 1853-1963

- Ted Corbitt – Part Three – 1964-2007

Sources:

- John Chodes, Corbitt: The Story of Ted Corbitt, Long Distance Runner

- John Jewell, “Notes on the Measurement of Roads for Athletic Events” http://coursemeasurement.org.uk/history–/jewell.pdf

- org.uk

- Ted Corbitt, “Measuring Road Running Courses.” https://www.rrtc.net/Articles/Corbitt.pdf

- Alan Jones, “The Jones Counter: Recalling the introduction of a device that revolutionized course measurement.” https://worldathletics.org/heritage/news/jones-counter-course-measurement

- com

- Road Runners Club New York Association Newsletter, Fall 1964. Fall 1970

- Long Distance Log, November 1966

- The Guardian (London), Oct 17, 1966

- Bill Jones, The Ghost Runner: The Epic Journey of the Man They Couldn’t Stop

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Sep 25, 1967

- Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), Dec 16, 1968

- Coventry Evening Telegraph (England), Oct 12, 1968

- Los Angeles Times (California), Nov 7, 1968

- Los Angeles Times West Magazine, Jan 10, 1971

- Sports Argus (England), May 10, 1958

- Coventry Evening Telegraph, May 15, 1958

- The People (England), Jun 8, 1958

- Birmingham Daily Post (England), Oct 27, 1969

- The Sacramento Bee (California), Oct 17, 1970

- “40 Year on: Ron Bentley and the 24 Hour World Record” 4 parts

- Daily Mirror (England), Nov 6, 1973

- Andy Milroy, “24hr Run History”