Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:15 — 37.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Andy Milroy

You can read, listen, or watch

An audio podcast episode has been added to this article.

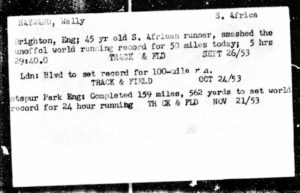

Early conditioning can be very important. Wally Hayward came from a very tough background. His father, Wallace George Hayward, the son of a coal agent, had been born in Peckham in London, England in 1880, and emigrated to South Africa sometime between 1901 and 1906, in his early twenties. It looks probable he actually arrived soon after 1904 when the sand bar which had restricted Durban Harbour to bigger ships was dredged and deepened. This allowed the weekly Union Castle passenger ships from Southampton to enter the port. Bearing in mind Wallace’s later employment, and absence from Union Castle passenger lists, it is possible that he served as a barman on one of these passenger ships, departing the ship at Durban.

Early conditioning can be very important. Wally Hayward came from a very tough background. His father, Wallace George Hayward, the son of a coal agent, had been born in Peckham in London, England in 1880, and emigrated to South Africa sometime between 1901 and 1906, in his early twenties. It looks probable he actually arrived soon after 1904 when the sand bar which had restricted Durban Harbour to bigger ships was dredged and deepened. This allowed the weekly Union Castle passenger ships from Southampton to enter the port. Bearing in mind Wallace’s later employment, and absence from Union Castle passenger lists, it is possible that he served as a barman on one of these passenger ships, departing the ship at Durban.

| On ultrarunninghistory.com, each article/episode takes about 30 hours of effort to research, write, script, edit, publish and publicize. Each month more there are more than 100,000 downloads of these history stories.

Help is needed to continue this effort. Please consider becoming a patreon member of ultrarunning history. You can become part of the effort to preserve and document this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

After arriving in Durban he met Cornelia Gerhardina Jacoba Kritzinger. Cornelia was the youngest of eight children of an Afrikaner farmer, Louis Kritzinger and his wife Rachel. The Kritzinger family had a 3000 acre farm in Zululand, then part of the British province of Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal). The three sons worked on the farm with their father and the women had a whole raft of household tasks to complete – baking and preserving, making and repairing clothes, sewing, knitting and cooking. The sisters took in turn to tackle each of these tasks.

Cornelia was born in 1878 but by her mid-twenties she seems to have rebelled against this demanding regime and left the farm for the city life of Durban. Perhaps the demands and deprivation of the Second Boer War had been the final straw. Cornelia got a job as a cook in a children’s home and some time in 1906/07 she met the younger Wallace Hayward. He had become a barman in a Durban hotel and the couple later lived in one of the hotel rooms.

On the 10 July 1908 Wallace “Wally” Henry was born, named after his father and his grandfather, Henry Hayward. Two years later a sister Agnes was born, then two years after that a brother Horace and finally a sister Gertrude. The names chosen show a great deal about the dynamics between the couple. Basically the children were named after Wallace’s siblings. None of Cornelia’s family had a child named after them. This was in the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War which had made such a horrendous impact on the Afrikaans. Wallace’s dominance in the naming of the children, may have been a response of a victor over the vanquished, but seems at the very least, insensitive.

When Wally was eighteen months old, the family moved to Johannesburg. Without skills, his father found it difficult to get work, and once again wound up as a barman in a hotel. Already a heavy smoker, he began drinking heavily. The Haywards had come to Johannesburg at the prompting of one of Cornelia’s sisters. The Kritzingers had been involved in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). Originally from Germany, three Kritzinger brothers came to South Africa in 1820 and two of them married Dutch women. A descendant, Pieter Hendrik Kritzinger, was a Boer general and guerrilla fighter during the Second Boer War.

Around 1914, when Wally was six, his father got a job working in a mine, eventually becoming a mine captain at the East Rand Propriety Mines, mining gold at Boksburg, a settlement not far from Johannesburg.

In 1916 Wallace enlisted in the South African Overseas Expeditionary Force (as the South African military contingent was called) and subsequently transferred to the Western Front in Flanders in Belgium. He was probably in the Third S.A. Infantry Regiment, raised in the Transvaal, that was part of the Somme Offensive in July that year.

A small holding, bought with some of the pension money, enabled Cornelia to put food on the table, or at least vegetables and fruit. A cow provided milk and hens, eggs. Cornelia’s childhood on a farm had prepared her well. As Wally later wrote she “was a very hard-working little lady.” Wallace’s condition deteriorated and after spending the last eight months of his life in bed he died in 1922, he was only around 42 years old.

In later life Wally was quite dismissive of Wallace. As I said, Wally felt Wallace had spent money, needed to feed and care for his family, on drink. However, it should be remembered that during the formative period of Wally’s life Wallace had either not been around, in the army or away working with the bakery, and then an invalid and bedridden before he died when Wally was only in his mid-teenage years.

Growing up immediately after the Anglo-Boer wars in Johannesburg, with an Afrikaans mother and English father, Wally would have faced an identity crisis, particularly when the learning of Afrikaans became enforced at school. However, It is apparent that Wally got his steel and toughness from his mother and his Afrikaans heritage as well as from his childhood; the great determination wedded to a very methodical mind that was needed to survive and care for his mother and siblings. His mother’s strong discipline gave rise to his strong self-discipline.

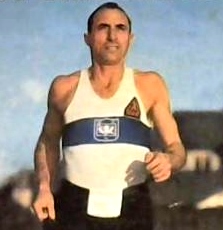

At the age of 16, Wally became an apprentice as a carpenter and builder. Wally was always a very methodical and meticulous individual in his work, and his mantra was “If you can’t do it properly, don’t do it at all.” His daughter later wrote “There has always been an obsessive determination to achieve the best, particularly where his running was concerned, and it is this plus his phenomenal ability which got him to the top.”

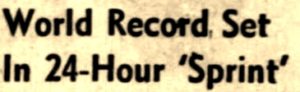

Race organiser, Vic Clapham, told Wally to ease up otherwise he would not finish. By the end his 29-minute lead had largely evaporated, he really struggled over the closing stages, only winning by 31 seconds from Masterton-Smith. A broken bone in his foot and a faulty diagnosis of a “strained heart” meant Wally did not defend his Comrades title. In 1932 he was fit enough to win the national 10-mile track title for a second time (56:52:28). In 1936 in the trial for the Berlin Olympics his calf muscle seized up and he had to withdraw from the race.

In 1937 Wally won another South African track title at the shorter 4 miles event in 20:34.6. As a result, he was selected for the 1938 Sydney Empire Games for the South African team at 3 and 6 miles. He won a bronze medal at the longer distance (250 yards back from the winner, Cecil Matthews ENG (30:14.5)) and was 4th in the shorter (14:24.4).

In the Second World War he joined the South African Engineers Corps, reaching the rank of sergeant, serving in North Africa and Italy. He was awarded the British Empire Medal for bravery for going into a blazing building.

Wally’s leg problems might been triggered by his decision to attune himself to marathons after near twenty years of track running. He had changed his style from running on his toes to running flat footed. This caused him weeks of agony as his no longer young muscles got used to the change. He was 40 in 1948. If he had run in the London Olympic Marathon, he would not have been the oldest runner, Britain’s Jack Holden was two years older than Wally.

In 1949 he won the Pieter Korkie ultramarathon. He also won the Korkie the following year, in between finishing second in the 1950 SA Marathon (2:42:21) and winning the Comrades for a second time. In 1951 he won the Comrades again and in 1952 he unexpectedly won the South African Marathon Championships in 2:37:00.5 and the selectors extended the South African Olympic marathon team, somewhat controversially, to three.

When Arthur Newton had come over to England in the 1920s, it had been to seek verification and confirmation of his ultra feats at 50 miles and the Comrades by reproducing that form in England. In 1927 he had run 14:43 for 100 miles in Rhodesia but once again he returned to England to test himself on the other famous pedestrian road, that from London to Bath. In 1928 he improved his time to 14:22:10 on the run from Box in Wiltshire to Hyde Park Corner in London, reputedly 100 miles. In 1934 he had taken a final shot at the course recording 14:06.

When Hardy Ballington had come to England in 1937 with the intention of repeating the Newton feats he had won an international London to Brighton and set a new best time for the Box-Hyde Park Corner event of 13:21:19.

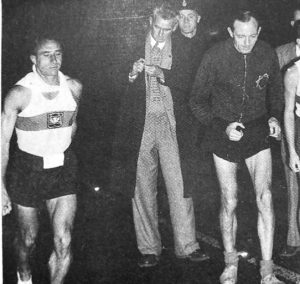

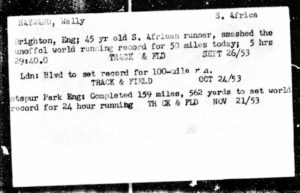

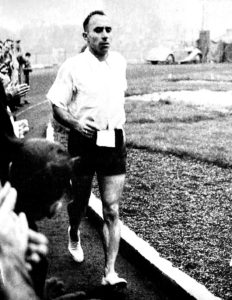

Just under a month after his run in 1953 Brighton, Wally set out from Box on his run to Hyde Park Corner in London. His competition included Derek Reynolds and the young Jackie Mekler. Wally was seconded by Pete Gavuzzi, Newton’s partner in the 1920s Pyle races across America. He reached 26 miles, close to the marathon, in 3:22:21, 50 miles in 6:01:31.

Arthur Newton was still not content. He now suggested that Wally try and break his (Newton’s) 24 hour world best, set indoors in Hamilton in 1931. (152 miles 540 yards/245.113 km.) Neither Pete Gavuzzi, nor Wally were very enthusiastic but did not want to disappoint the venerable and iconic Newton.

The race went smoothly to 100 miles, (he reached 50 miles in 6:06:34) where a brief rest of ten minutes had been planned, but Wally was so tired at that point he wanted to come off for shower and a massage. It was only with great difficulty that after half an hour he was persuaded to continue. By then he had stiffened up and ran differently – walked for a while, then ran for awhile then walked again before he gradually ran heavily and awkwardly. He struggled on like this to the end of the 24 hours.

Pete also reported on Wally’s food and liquid intake in the 24 hour. During the race Gavuzzi and Newton fed him on egg custard and rice. He also had warmed lemon juice laced with sugar and with salt to ward off cramp. (Enough salt to cover a sixpence.) He drank tea and coffee with plenty of sugar – he got through 2lb/1 kg of sugar during the race, with the occasional fizzy drink to wash his mouth out. During the race he lost 7lb/3.1 kg in weight.

On his return to South Africa Wally was to later win the 1954 Comrades in record time, his fifth win and the first man since Arthur Newton to hold both the Up and the Down Records in the Comrades.

Read more details of Hayward’s 100-mile races.

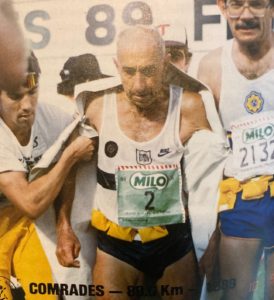

Twenty years later he was reinstated and soon made an impact on veteran events, including the Masters World Championships. Thirteen years after his reinstatement, Wally’s ambitions would return to the Comrades, Les Hackett became involved in running with the now quite elderly Wally but was under strict instructions not to talk to him. His hyper-strict regime involved running at a prescribed rhythm – he took two strides and inhaled, then took two more strides and exhaled. Talking disrupted that rhythm.

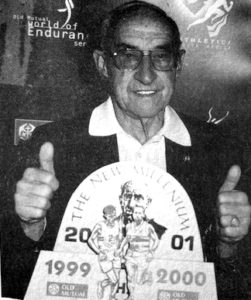

Wally Hayward’s opportunities to shine on the world stage were largely restricted by injury or the War. He won FIVE Comrades Marathons but arguably could have won at least seven, but for his suspension for receiving money. His strength made him well suited to the 100 mile and 24 hours. Arguably in good conditions he could have got closer to 12 hours in the former event and 170 miles/273 km in the latter – a distance he was aiming for in 1953. His times in the London to Brighton were to be surpassed by Tom Richards in 1955, who reached 50 miles in 5:12:37 and the finish in 5:27:24. Richards was a former top class marathon runner, missing out on the gold medal for the Olympic event by just sixteen seconds in 1948. Interestingly he was around the same age as Wally, when he had run the Brighton, born in 1910. Subsequently Ron Hopcroft surpassed his Bath Road 100 mile time in 1958, running 12:18:26, running from Hyde Park Corner to Box. Wally’s 24 hour mark lasted longer, only being surpassed by Ron Bentley in 1973, close to twenty years later. As a South African record it was to last sixty years until finally surpassed by Johan Van Der Merwe in 2013!

Author’s Note

I would like to thank Riel Hauman and Peter Lovesey for their help with this article.