Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:27 — 37.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

But the spark of running or walking 100 miles on foot still smoldered during the next two decades despite the severe difficulties of the Depression and World War II. Isolated 100-mile accomplishments took place to remind the public what the human body could do, but 100 miles was still considered to be very far and out of reach by all but freakish athletes.

Gruber’s “softies”

Gruber’s comments cause a bit of an uproar and debate across America. Newspaper commentary included, “We know of no way to prove the general is in error and of no way to prove that he is right.” But young men across the country found a way to provide some anecdotal proof that Gruber was wrong.

The general did hear about it. Gruber wrote a letter of congratulations to the youth stating that he hoped the performance “would inspire other young men to watch their health and keep themselves in good physical condition.” Morton was soon hired by the army as messenger for a commanding officer and made daily walks and runs of 8-15 miles to deliver messages.

“The oldest contestant, Milton Graham, a 30-year-old truck driver, gave out at the end of eight miles, complaining a football knee was troubling him. As the sun climbed and the mileage passed 20 miles, there was little running going on. Ted Morton collapsed three times on his fourth 6-mile lap, but he recovered sufficiently from severe leg cramps to finish second, dropping out at the 44-mile point.”

The notoriety Morton received for his running exploits continued to spur him on. In September 1941, he attempted to run 100 miles in less than 24 hours, going from Nevada, Missouri to Kansas City, Missouri. Physicians warned him that he should not plan to run the entire stretch at one time. He ran on U.S. highway 71 with the help of pacer Frank Grantello. Morton’s girlfriend, Betty Grantello, daughter of his pacer, rode along providing support from a car. His crew said he ran 6-10 miles at a stretch and then rested 10-15 minutes. Morton was successful and reached 100 miles in 23:54.

War-time 100-milers

A Dutch marine, “Bert” who visited the USO Club at Camp Davis, North Carolina, told an interesting tale to those there. When the Germans closed the schools in Holland, the students went off to work on the outlying farms. Bert became a farmhand about 100 miles from his home city of Amsterdam. He said, “Two days after Christmas I was in the field, and looking up, saw my mother standing close by. Thinking I was dreaming, I rubbed my eyes to wipe away the tears. Then my mother spoke saying ‘Merry Christmas, son.’ It really was my mother. She had walked the 100 miles to be with me on Christmas, but the journey had taken her longer than she had anticipated, and so she was two days late.”

Rangers in the United States Army received especially tough training. “Their training included toughening up day and night exercises in which they often marched 100 miles in two days with little rest and few rations. Such marches led them through rivers and up precipitous cliffs. They wiggled through barbed wire and dense undergrowth, and to simulate battle conditions live bullets whizzed over head or kicked up dust behind them.”

Lt. Omar N. Bradley, who at one time was overall commander of American troops fighting in France, earlier had served at Fort Riley, Kansas where his horse-drawn artillery battery was the first known unit to complete a 100-mile forced march in less than 24 hours! Yes, even in the army sub-24-hour 100-milers were accomplished by men in uniform.

100 miles across the Sahara Desert

In 1943, Sergeant Alban Petchal of Steubenville, Ohio was on a plane flying as a gunner, heading to the war in Africa. When they reached Central Africa, near a combat zone, Petchal’s plane became separated from the rest and wound up running out of gas over the Sahara Desert. “They rode the plane into the sand dunes, which were everywhere, and about two stories high. They bounced across the tops of four and slammed head on into the fifth. All three men were painfully hurt.”

The men crawled out of the wrecked plane, patched up their wounds and made a shelter out of their life raft. After three days the three wounded men decided that they would have to walk out of the desert. They sprinkled the plane with gasoline and set it on fire. They then started off on what they knew would be perilous 100-mile journey carrying a five-gallon can of water slung from a stick. Along the way, they battled sickness and freezing nights. Two officers became delirious and quarreled violently. “Finally they found tracks, and the same day ran onto a camel caravan. The Arabs fed them and invited to join them. The boys tried to ride the camels, but it was so rough and horrible that they finally had to get off and walked.” After walking a total of 100 miles across the desert they finally arrived at a French unit.

Prisoners of War 100-mile marches

After four months of intense battle, on April 9, 1942, American troops surrendered to the Japanese. The captured Americans and Filipinos were subjected to a torturous march of more than 65 miles during which thousands died. Many books have been written about the event.

Lt. James Kermit Vann described his “100-mile death march.” He felt lucky that he survived the march, but he suffered terribly. He wrote, “This prisoner army of almost 3,000 most of them dirty ragged and unshaven was led to a road and under cloudless skies was ordered to march. None of us got any water until nightfall. We had passed many natural wells off the road, but the bayonets wouldn’t let us near them.

At times we were ordered to sit down in the road under the hot sun. Anyone who tried to stand up was knocked down. Anyone who tried to stretch out his legs was forbidden to relax. We sat there for four or five hours. It wasn’t long before I came down with malaria, beri-beri, dysentery and other ailments. It wasn’t until the fifth day that we were given any food. There was almost no conversation among the men. They were too sick, too weak, too hollow-eyed and sunken-cheeked to care about anything except home. I was so weak and dizzy that I don’t remember too much about the rest of the march. I believe we made the 100-mile march in seven days.” 100-mile runners are concerned about losing too much weight during their events. Lt. Vann lost 55 pounds during his march, to a weight of 105 pounds.

100 miles to Germany

In 1944, near the end of the war in Europe, the German army was in retreat from France. Thousands of Allied prisoners were being held at Montigny, France. They were told by their German captors that they were going to be marched 100 miles through the war chaos to Germany. John Mecklin (1918-1971) was an American correspondent who had been taken prisoner and wrote about the terrifying 100-mile march. About 2-3,000 men began the 100-miler in a column about a mile long.

“When we started, we were in reasonably good spirits, but that did not last long. After an hour or two the whole column moved in sullen beaten silence.” The men and the Germans were in constant fear of being bombed by American planes who had no idea that a prisoner 100-mile march was taking place. “We made an ideal air target. The road ran almost entirely through open, rolling fields. Even the ditches were too shallow for good protection. I carried a blanket, a musette bag, a canteen of water, toilet articles and two cans of German tinned meat, and with each step the load became heavier.”

The Germans set the initial pace, but before long, the prisoners who were younger and in better shape, took over the pace. Finally, the exhausted Germans decided to use a bus to shuttle prisoners in a round-robin fashion up the road in five-mile stretches. Cheating the 100-mile course for stretches was a luxury as they rode with their guard in a corner of the bus with a revolver balanced in his lap.

At Bourbonne-les-Bains, the 100-miler became a pure “endurance contest.” They walked steadily for three hours without rest. The Germans knew they were racing ahead of the advancing Allied forces and were very nervous. Finally, the bus crashed into a ditch and was broken down. There would be no more rides during this 100-miler. When a small pick-up truck came by, the Germans elbowed each other to pile in, one sobbing that he could walk no father. But the Americans had no choice but to continue their long walk.

“The whole atmosphere among the men in the column was beginning to change. They became a sweaty, dragging anguish. Panic was beginning to seep into the minds of the men on that endless road, while the sun beat down and seared everything. When the column passed villages, we prisoners would straighten up and walk firmly.”

As they continued on, the Germans started talking in low voices and the prisoners feared that they would soon be shot. A guard told them that they could run into the woods and escape around the next bend. Was he trying to give them a reason to get shot? Mecklin and few other went off the 100-mile course and dashed into the woods. They threw away all that they carried and ran at top speed and then tried to find someone to put them up for the night. Finally, at dusk three men came toward them and to their relief they wanted to help. “They took us to an ancient mill on the edge of the village and before long we were the center of attraction at a full dress banquet. Fifty people came to visit us within an hour. We went out with the people to stand in the square and sing the French nation anthem. An officer said, ‘You are free. The Germans will not be back.’” It was one of the greatest celebrations for DNFing a 100-miler in history.

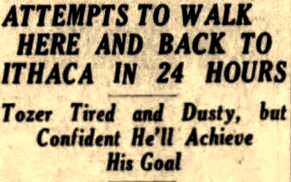

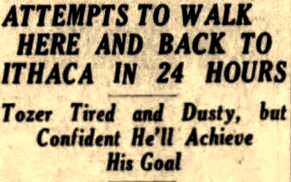

Frank Tozer – prolific 100-mile walker

He also became a bicycle enthusiast and in 1926 pedaled all the way to Florida. Tozer gained wide fame in 1938 when he set out from Ithaca New York, accompanying two others, a policeman and a fireman, on a 34-mile walking race to Elmira New York. Tozer finished first in 7:50, beating the policeman, Daniel B. Flynn, by nearly three hours. After arriving, Tozer declined a ride home and completed his return trip in 8:20.

But the 59-year-old walker had difficulty on his return trip. He tried to take a shorter route but made a wrong turn and walked bonus miles. When the 24 hours expired, he was still about 20 miles from the finish. He learned the he really needed to have a crew car drive along with him. He stated, “When you are walking against time, you don’t have any time to stop and make inquiries. I would have been better off with help like that.”

Later in 1943, Tozer returned to Ithaca and was employed at the Cornell University Library. In November 1945, at the age of 66, he measured off a two-mile stretch and walked it over and over again to reach 100 miles during a 24-hour period. This walk was very challenging because of a bitter cold wind. He was paced by Orhan Illgaz a college student from Turkey who usually walked 6-7 miles per day. For 1946, Tozer walked around Cayuga Lake and through several towns to again accomplish 100 miles.

During May 1947, he decided to walk 100 miles from Ithaca to Rochester, New York to deliver a letter to the newspaper there and to visit relatives. His first attempt was a bust because of a bad rainstorm along the way that caused bad blisters. But in July he was successful and finished his 100 miles in less than 24 hours.

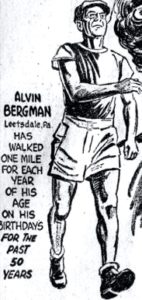

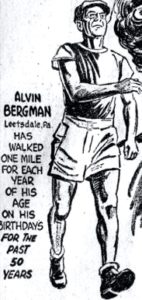

Mote Bergman

Walking 100 miles in a day became Bergman’s goal. In 1939 at age 52, he took his walking talents to the Leetsdale High School track where he walked/ran 100 miles in 22:05 on the quarter mile track. He would accomplish several other sub-24-hours 100s in the future. It was reported, “He frequently walks 20 miles before breakfast just to get up an appetite, and he always fasts as part of his training before a long distance stroll.”

On August 26, 1950, Bergman accomplished another sub-24-hour 100-mile walk. He walked through several towns with a car following to measure the distance on the odometer. When it showed 50 miles, he turned around and started back. He finished in about 23:30, which was one of the first sub-24-hour 100-milers accomplished by an American in the post-war era of ultrarunning.

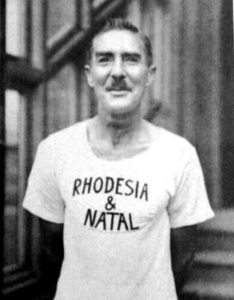

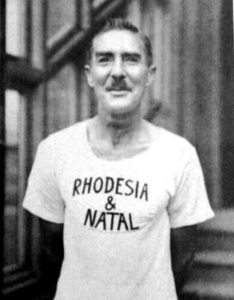

Arthur Newton

Hardy Ballington

He did, in 1933, and finished in a surprising 4th place with 8:01. The following year he won the Durban Athletic Club Marathon in 3:08. But he soon put his concentration on the ultra-distances and believed he could win Comrades. He would become one of the greatest of all the Comrades champions.

Ballington’s success continued, winning Comrades again in 1934 and 1936. During the depression era, he became known as the world’s greatest ultra-distance runner.

Ballington’s London to Brighton Record

In 1937, Ballington skipped running Comrades and instead wanted to go after Arthur Newton’s 50 and 100-mile records that he set in England. Newton was the driving force behind Ballington’s attempts that were sponsored by News of the World. Ballington traveled to England in April with his expenses paid for him. Newton paid special attention to Ballington, escorting him by bike on his training runs. He logged an astonishing 1,100 miles on training runs in one month.

Ballington’s 100-mile World Record

Through the challenging World War II times of the 1940s, not much is known about Ballington’s running efforts, but in 1947, after the war, Ballington won the Comrades Marathon for the fifth and final time at the age of 35. He went on to be a travel agent and by 1966 had flown around the world six times visiting the major cities of the world. In 1969 Comrades established the “Hardy Ballington Trophy” for the first novice runner to finish the race.

College Students

The parts of this 100-mile series:

- 54: Part 1 (1737-1875) Edward Payson Weston

- 55: Part 2 (1874-1878) Women Pedestrians

- 56: Part 3 (1879-1899) 100 Miles Craze

- 57: Part 4 (1900-1919) 100-Mile Records Fall

- 58: Part 5 (1902-1926) London to Brighton and Back

- 59: Part 6 (1927-1934) Arthur Newton

- 60: Part 7 (1930-1950) 100-Milers During the War

- 61: Part 8 (1950-1960) Wally Hayward and Ron Hopcroft

- 62: Part 9 (1961-1968) First Death Valley 100s

- 63: Part 10 (1968-1968) 1969 Walton-on-Thames 100

- 64: Part 11 (1970-1971) Women run 100-milers

- 65: Part 12 (1971-1973) Ron Bentley and Ted Corbitt

- 66: Part 13 (1974-1975) Gordy Ainsleigh

- 67: Part 14 (1975-1976) Cavin Woodward and Tom Osler

- 68: Part 15 (1975-1976) Andy West

- 69: Part 16 (1976-1977) Max Telford and Alan Jones

- 70: Part 17 (1973-1978) Badwater Roots

- 71: Part 18 (1977) Western States 100

- 72: Part 19 (1977) Don Ritchie World Record

- 73: Part 20 (1978-1979) The Unisphere 100

- 74: Part 21 (1978) Ed Dodd and Don Choi

- 75: Part 22 (1978) Fort Mead 100

- 76: Part 23 (1983) The 24-Hour Two-Man Relay

- 77: Part 24 (1978-1979) Alan Price – Ultrawalker

- 79: Part 25 (1978-1984) Early Hawaii 100-milers

- 81: Part 26 (1978) The 1978 Western States 100

- 87: Part 27 (1979) The Old Dominion 100

Sources

- David Blaikie, “The history of the London to Brighton Race”

- Rob Hadgraf, Tea with Mr Newton: 100,000 Miles – The Longest ‘Protest March’ in History

- John Cameron-Dow, Comrades Marathon – The Ultimate Human Race

- Albuquerque Journal (New Mexico), Oct 10, 1929

- Morristown Gazette Mail (Tennessee), Jul 2, 1930

- The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada), Dec 30, 1933

- The Albion Argus (Nebraska) Mar 22, 1934

- The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), May 23, 1937

- The Observer (London, England), May 23, 1937

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Jul 21, 1937

- Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), Jul 18, 1938

- Press and Sun Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Aug 3, 1938

- The News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina), Jun 17, 1940

- The Kansas City Star (Missouri), Jan 30, Jun 1,20, Aug 3, 1941

- Lancaster New Era (Pennsylvania), Jan 30, 1941

- Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), Feb 4, 1941

- The Times (Shreveport Louisiana), Feb 8, 1941

- The St. Louis Star and Times (Missouri), Sep 22, 1941

- The Jackson Sun (Jackson, Tennessee), Jul 21, 1941

- Wilkes-Barre Times Leader (Pennsylvania), Jul 21, 1941

- The Kansas City Times (Missouri), Jun 27, Jul 11,21, Sep 22, 1941

- The Age (Melbourne, Australia), Aug 1, 1942

- The Cushing Daily Citizen (Oklahoma), Aug 19, 1942

- The Amarillo Globe-Times (Texas), Jan 27, 1943

- The Gettysburg Times (Pennsylvania), Jun 2, 1943

- The Miami News (Florida), Jun 3, 1943

- The Evening Times (Sayre, Pennsylvania), Oct 13, 1943

- Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Mar 11, 1944

- Dayton Daily News (Ohio), Sep 24, 1944

- The Bangor Daily News (Maine), Aug 15, 1944

- The Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), Apr 19, 1945

- The Knoxville Journal (Tennessee), Nov 25, 1945

- The Daily Reporter (Greenfield, Indiana), Dec 15, 1945

- The Ithaca Journal (New York), Aug 27, 1935, Aug 2-5, 1938, Nov 26, 1945, Sep 17, 1946, May 27, 1947, Jan 12, 1950

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Jul 2, 1947

- The Tipton Daily Tribune (Indiana), Aug 30, 1957

- The Sydney Morning Herald (Australia), Mar 18, 1966