Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:36 — 38.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

The Comrades Marathon held in South Africa is the world’s largest and oldest ultramarathon race that is still held today with fields that have topped 23,000 runners. The year 2021, marked the 100th anniversary of Comrades Marathon.

| Help is needed to continue the Ultrarunning History Podcast and website. Please consider becoming a patreon member of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

This episode on Jackie Mekler is the sixth part of a series honoring Comrades and South African ultrarunning.

- 80: Comrades Marathon – 100 years old

- 59: Arthur Newton

- 83: Hardy Ballington – The Forgotten Great Ultrarunner

- 84: Wally Hayward (1908-2006) – South African Legend

- 85: Mavis Hutchison – Galloping Granny

- 86: Jackie Mekler – Comrades Legend

This episode is largely based on Jackie Mekler’s autobiography Running Alone: The autobiography of long-distance runner Jackie Mekler where you can read far more details about his running career.

Childhood

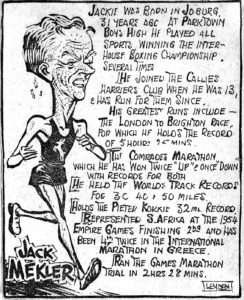

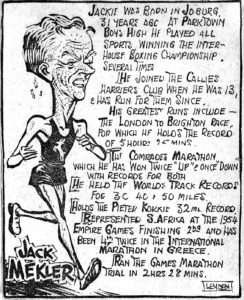

Jack “Jackie” Mekler was born March 4, 1932, in Johannesburg, South Africa. His parents, Mike and Sonia Mekler emigrated to South Africa from Eastern Europe in the 1920s with little more than the clothing on their backs. His father had studied to become a dental mechanic but was unable to find employment and the young couple struggled to survive financially. Children were born, first Hannah and then Jackie.

The Meklers first lived in a large room with family friends in Bertrams, a Johannesburg suburb, A few years later, there were able to afford buying a fairly new home nearby. Sadly, Jackie’s mother, a nurse, developed Parkinson’s disease that crippled her requiring the young children to care for her. His father worked long hours selling fruit from the back of a horse-drawn cart trying to support the young family.

Jackie wrote, “Physically, I was always small and underweight for my age – facts that caused my parents considerable concern in my preschool years. I remember regular visits to the local hospital, where I was put on innumerable courses of ‘pink pills’ and tonics.”

Life at an Orphanage

When red-headed Jackie was nine years old, his mother became so ill that she needed to be sent to a nursing home. His father just couldn’t deal with raising children and also working long hours, so he decided to send Jackie and Hannah to live at the Arcadia orphanage. Jackie came home from school one day to find a large black sedan parked in front of their house waiting to take them to the orphanage. The two children cried and argued with their father, who bribed them with a half a crown each if they agreed to go. They no choice and moved into the orphanage. A couple weeks later their father visited with news that their mother had died.

Arcadia was a Jewish orphanage that was established at a villa in 1923. Jackie Mekler was required to participate in Jewish rituals and rules which was a major adjustment for him. There were about 300 children who lived in large dormitories, each with a locker for their few personal belongings. The children were ruled with strict discipline. Punishment involved missing meals or being sent to the superintendent’s office for a “caning.”

The place did have sporting facilities and Mekler grew up competing with boys in various sports, mainly cricket and soccer, but lived in an environment where the adult caretakers lacked compassion. He learned early on to become self-sufficient. He said, “I became hardened, both physically and emotionally. I learned that I would have to work for things that I wanted and that nothing was going to just fall into my lap.”

Growing older into his teens, Mekler attended Parktown Boy’s High School which was really his first experience mixing with boys from outside his orphanage environment. He took part in cricket, rugby, and boxing, but as a smaller boy was always on less-skilled teams.

Starting to Run

At the age of thirteen, Mekler decided to improve his health and fitness by running. He recalled, “Early in the morning on December 26, 1945, I slipped out of the dormitory while everyone else was still asleep and walked down the long curved, concrete driveway lined with Jacaranda trees. I waited for the second arm of my watch to reach zero so that I could time my first half-mile run. It didn’t take me long to realize that this first run would develop into my life-long passion, if not obsession. It was the one activity I could undertake easily – alone.” He began running three times each week and dreamed of breaking the 4-minute mile barrier.

As he became committed, he started to keep a diary that included his running miles, a record he kept for the next 22 years. By age fourteen, he had run 493 miles. He usually ran during the early morning before the other boys woke up at the orphanage dormitory. One morning he decided to find out how far he could run and reached six miles before he started to feel tired. “I noticed a marked improvement in my standard of fitness, which made me feel good. I began to develop more self-confidence as my fitness improved. These runs gave me an opportunity to escape the constraints of the orphanage. Being out on my own, free and able to enjoy the early morning peace and tranquility, was of huge value to me.”

As a lone orphan runner, he was self-taught, and read everything he could find about running in the newspaper, pasting articles into a scrapbook. He would sneak out of the orphanage on Sundays to watch cross-country meets. There, he would listen to runners chatting at events and collected autographs as a way to meet the runners.

Joining a Running Club

Long Distance Running Begins

Leaving the orphanage disrupted Mekler’s High School education. Needing a trade, he became an apprentice in the printing industry but continued to run in three-mile track races over weekends or after work. His first long-distance race of 20 miles came in 1950, running from Johannesburg to Krugersdorp, when he was almost 18 years old. He experienced the thrill of passing weary runners toward the end of the race and finished 17th out of 31 finishers.

During 1950, Mekler’s running ability continued to improve as he traveled to many towns competing in cross-country races. He ran a portion of the famed Comrades Marathon course (54 miles) and imagined himself running and winning Comrades one day.

Later that year, he entered his first marathon in Johannesburg. The three-lap course started and finished at Wembley Raceway Stadium. After 18 miles he cramped up, started walking spells, and finished in 3:12:53. “I was disappointed with my run and sat dejectedly in the changing room afterwards, pondering what had happened. I believed that I could easily improve my marathon time by 10 minutes.”

In 1951, Mekler watched South African legend, Wally Hayward (see episode 84) win a 38-mile ultramarathon. “I vividly recall marveling at the tremendous power with which he ran, effortlessly brushing aside all opposition. opposition. On that occasion he was well-tanned, a picture of health, vitality and fitness. I wondered if I could ever compete in his class. Of course, his autograph was one of my prized possessions.”

Early Ultrarunning

In 1952, Mekler increased his training to 130-mile weeks, with long Sunday runs of 30-50 miles which was very unusual at that time. Everyone on his team ran without socks. They rubbed the inside of their tennis shoes with soap which formed a cushion.

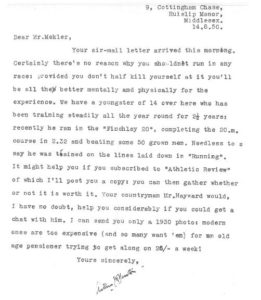

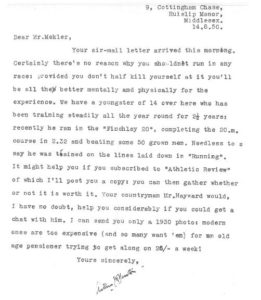

Mekler continued to mostly learn the art of running from books. He responded to an advertisement for Arthur Newton’s book and was shocked to receive a reply from the great runner himself. This started a long-distance friendship with the patriarch of South African running who then lived in England.

Mekler mostly continued to run alone early in the mornings before work. Once he even got up at 2:30 a.m. to run 36 miles for five hours before work. He said, “I was quite content and even preferred running long distances on my own. Frankly, I knew of no one who would have been able or prepared to accompany me. The quietness and solitude I experienced in the dark on those early mornings and the wonderful clarity of the fresh, cool air was just so inspiring.”

The large city of Johannesburg was his running world at night. “On these early morning runs I kept to well-lit streets that were totally deserted apart from an occasional late-night reveler, a few milk delivery vans; and the municipal cleansing department hosing down the streets. Butcher shops were always the first to open, followed by bakeries. The few people who were around seemed to take little notice of the solitary idiot pounding the streets.”

Mekler ran to work many days. He needed to make sure he was there at 7:30 a.m. and working by 7:45 a.m. “One day I was three minutes late. The foreman stormed across the floor and blasted Mekler for being late. He asked, ‘What’s more important, your running or your work?’ I gave the wrong answer and I was suspended for two weeks. I didn’t stop me from running but I made sure I got to work earlier.”

Mekler’s First Comrades

At the pre-race meeting at a Durban hotel, final instructions were given to the small group of runners. Five-time winner Hardy Ballington addressed the runners and gave them some advice. Race-day morning arrived on July 14, 1952. Mekler wrote, “I got up at 5 a.m. to go through the all-important pre-race ritual: wash, shave, check my kit, grease around the armpits and inner thighs, and putting sticking plaster onto the nipples.”

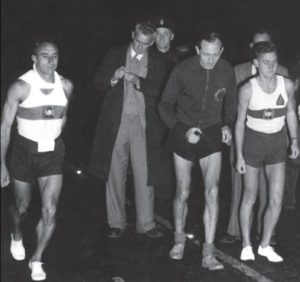

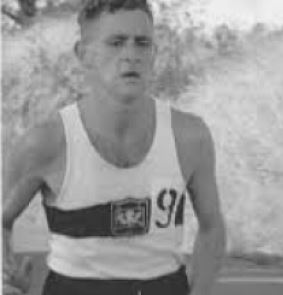

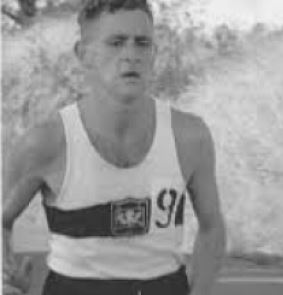

Comrades began that year in front of the Durban City Hall. Mekler was only 20 years old, five-foot-six, and weighed just 118 pounds. “It was cool and dark in the hushed silence in those last few seconds of patient expectation just before the six o’clock chimes of the City Hall clock and the crack of the Mayor’s pistol.”

“On cresting the monstrous hill, I recovered and ran all the way to the finish, even increasing my pace over the last two miles. As I ran the final lap around Alexandra Park, I experienced a strange, sad feeling that the race was over, which reflected the overall disappointment of my run.” He finished in seventh place, in 7:45:03, winning the Hardy Ballington trophy for the first novice to finish.

After 7,000 miles of training and 116 races, at the young age of 20, he won his first marathon a few months later in October 1952 with a time of 2:42:56. He recalled, “It was a wonderful feeling to taste success at last. I had worked toward this victory for so many years and in spite of frequent injury and indifferent performances, I never doubted that I would eventually succeed.” More wins started to come as he continued to run in nearly every race that came along, both long and short.

London to Brighton

In 1953, Mekler, age 21, wanted to make the ultrarunning pilgrimage to England, to run the most prestigious ultra at the time, London to Brighton (52 miles). Funds were raised to send him on the long trip. To prepare, he trained with legendary Wally Hayward who poured his ultrarunning experience onto Mekler.

In England, they stayed with ultrarunning great, Arthur Newton. Mekler was thrilled to meet the legend for the first time. “The door opened and there stood a lean, elderly gentleman dressed in grey flannels with a grey lightweight jacket. He had a kind, gentle face, his thinning grey hair combed straight back. In his hand he held a pipe. Here, after our 6,000-mile journey, stood Arthur Newton, the most famous long-distance runner the world had ever known. I just stood, utterly overawed and totally speechless!” Training quickly continued with Newton following along on his bicycle.

Newton introduced Mekler to a helpful running shoe modification. South African runners had been running in “zero-drop” tennis shoes. Newton introduced them to a modification of gluing a crepe heel on the sole of the shop to introduce an elevated heel to alleviate tension on the Achilles tendon. This modification away from “zero-drop” proved to be very successful in Mekler’s future running career.

After several weeks of training in England, the race day for London to Brighton arrived on September 26, 1953. Hayward was the favorite. Mekler recalled his pre-race jitters, “This was my most important race to date and my first ultramarathon that included runners from overseas.”

At 7 a.m., 52 starters raced off across Westminster Bridge in thick fog on their way to Brighton, 52 miles away. Hayward dashed off with the leaders and Mekler settled into about 20th place. At the halfway point he realized that he was too far back and needed to run more seriously. He put on an impressive charge and finished in 4th with 5:48:03, four minutes better than the existing course record. Hayward crushed the record winning in 5:29:40. Mekler said, “I was delighted with my run, largely because I was a lot closer to Wally than I had been in the Comrades.”

Mekler’s First 100-miler

The next running event in England for Mekler was to participate in a 100-mile world record attempt with Hayward on the Bath Road from Box to London. It was sponsored by The News of the World newspaper. This would be Mekler’s first attempt to run the 100-mile distance and some speculated that Mekler could beat Hayward.

Plans were put into place. Mekler recalled, “A race as long as 100 miles naturally involved complex logistical arrangements, not the least of which were managing the traffic on a major highway.” The police suggested alternative courses, but Newton and Hayward insisted on the traditional course. Approval was given as long as they called it a “time trial” instead of a race with only three runners, Hayward, Mekler, and Derek Reynold. John Legge was also allowed to run but had to start two hours later.

The press thought the event was crazy and called it “100 miles of murder.” Mekler lacked confidence that he would do well, especially with leg pain from excessive training weeks of 147 and 171 miles leading up to the 100-miler run. He said, “I had never run such a great distance before. The thought of running 40 miles further than I had ever run was something that had to be considered right from the very start.”

The historic 100-mile run began at 3 a.m. on October 24, 1953, at the Bear Inn, in Box. They would be duplicating the record runs accomplished years earlier by Arthur Newton and Hardy Ballington. From the start, Hayward and Reynolds pushed ahead. Mekler decided to stick to his own even pace and gradually dropped further and further behind. After 25 miles he was 13 minutes behind the leading Hayward. After going through 50 miles in 6:25:10, he was able to pass Reynolds. At 74 miles his crew car which had not been crewing him very well, started providing him better support. He said, “I enjoyed an ice cream and some home-made egg custard. I also brushed my teeth, had a general clean up and felt much refreshed.”

Mekler’s main goal was not to beat Hayward, but to finish better than the existing 100-mile world record held by Ballington of 13:21:19. As he approached London, the traffic became heavy and endangered his finish goal hopes. But Mekler ran hard, producing negative split times. “Finally, to my great joy, Hyde Park appeared, and I had to run through the park itself to the finish line at Hyde Park Corner. There was still a large crowd waiting at the finish and several young athletes in tracksuits came to run the last half mile with me. I thought I would surprise them by putting in a fast finish, leaving them gasping behind.” He finished his very first 100-mile attempt in 13:08:36 beating the old world record by 12 minutes.

Mekler shortly started his trip back to South Africa and again ran laps on the ship deck during the voyage. Reflecting on this historic trip he wrote, “I felt that the 1953 trip to Britain had done me the world of good in every way. I was now a much stronger runner with far more confidence as a runner and as a person. The privilege of meeting and getting to know Arthur Newton was life-altering.”

World Records

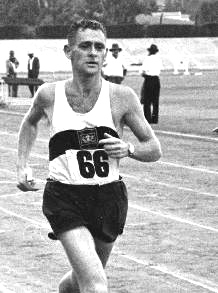

In the fall of 1954, Mekler was encouraged to go after Derek Reynold’s 40-mile and 50-mile world track records. He decided to make the attempt on his home track at Delville Stadium, in Germiston, South Africa at an altitude of 6,000 feet.

The track surface wasn’t especially fast, a grass surface and the inside lane was roughed up by rugby player boots. In the pre-dawn hours, cars were positioned with headlights directed on the track for the start. There were quite a few spectators who came to watch. Two other club members started off with him. “The crack of the starter’s pistol echoed through the suburbs of the sleeping city and the challenge was on. Soon the sun peeped over the horizon and the car headlights were no longer necessary.”

Mekler, age 22, started off strong and knew that he needed to complete each lap in less than 99 seconds in order to break the 50-mile world record. He cruised through the marathon mark in 2:47:25 but started to tire at 35 miles. This made him shift his primary goal toward the 40-mile record. “I started taking more frequent drinks of lemon squash, glucose and salt together with regular sponges as by now the sun was beating down.” Forty miles came and he beat the record by a minute with a new world record of 4:18:14.

“Having tucked away this record I was tired. It seemed to have taken all my effort to clinch it, and now I had to face another 40 laps of continual grind around the parched track.” He tried to envision that he was then just running a simple 10-mile run. The crowd became enthusiastic. His handler, Fred Morrison kept screaming at him. In the end he finished with a new 50-mile track world record of 5:24:57, beating the previous mark by more than five minutes. Unknown to him at the time, Mekler also lowered the world 50 km track mark by about two minutes to 3:25:29.

The news press wasn’t very complimentary, not giving much value to running at ultra-distances. They thought the marathon distance had true value and that this was just a publicity stunt. Mekler, the youngest ultrarunner ever to set a world best, ignored it all and knew that since his record was set at altitude, that others would come along and break it if they ran at sea level. (Indeed, three years later, Gerald Walsh of South Africa improved the record by seven minutes in England.)

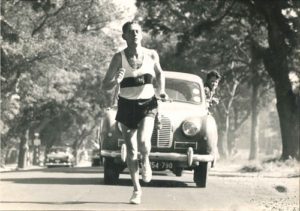

Comrades Champion

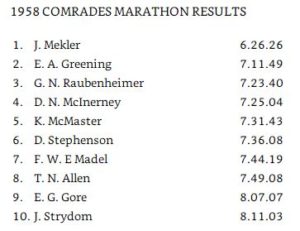

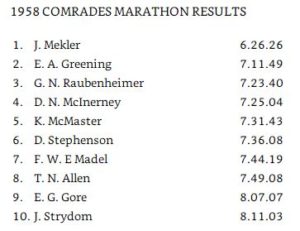

In 1958, at age 26, Mekler had been running for 13 years. He had already covered 35,000 miles in training and racing, but he still had not won the jewel of running in South Africa, the Comrades Marathon. After a long absence of five years, he toed the Comrades start line on May 31, 1958, with 60 runners. “The atmosphere at the Durban City Hall was awe-inspiring though tempered somewhat by the realization I had not given too much thought or proper preparation.”

Two years later, in 1960, Mekler broke Hayward’s “up” Comrades record becoming the first runner to break six hours, winning with 5:56:32. Some compared it to breaking the four-minute mile barrier. He ranked it as being one of his finest runs ever. When asked how long he had trained for the race, he replied, “Fifteen years.”

1960 London to Brighton

Mekler’s Germiston Callies team decided to send a team to run the 1960 London to Brighton. Mekler headed up the team. Sadly, Arthur Newton was not in England to greet him this time. He had passed away the year before. This time Mekler took a flight and arrived ten days before the race. His chronic knee pain resurfaced in the cool London weather in the days leading up to the race. Peter Gavuzzi, Newton’s longtime running partner agreed to train and crew Mekler.

His knee improved and he lined up at the start with fifty other runners. “The early morning mist should have made for pleasant running, but I was too busy nursing my knee over the first few miles, literally dragging it along as if it didn’t belong to me. In spite of this handicap, I was most surprised to find myself right up with the leaders. I continued to limp along as fast as I could until at eight miles, I actually found myself in the lead.” A runner he passed called out, “Hey, I thought you were supposed to have a sore knee.”

The pain decreased and he ran splits close to record time. He reached the marathon mark in 2:36, but by mile 38 was 2.5 minutes behind record pace. “This was a great disappointment and I realized very clearly that unless I did something desperate, I would have no chance of beating the record.” He pushed harder, not satisfied just to win. He wanted the record. Gavuzzi egged him on, jumping in and out of the crew car.

100-mile World Record Attempt

After winning London to Brighton, like Newton, Ballington, and Hayward before him, just three weeks later he went to try to break the 100-mile world record on the Bath Road.

A cold wind blew on his exposed legs, and it seemed impossible for him to warm up. At seventeen miles he was two minutes behind record pace. He said, “I knew I was not running as freely or as easily as I had hoped.” He had his first drink there, bottled lemon squash with glucose and salt and went on and hit the marathon mark in 3:04, still two minutes behind the record pace.

“As the darkness of night gave way to the cold, the first hint of trouble occurred in a pain behind my right knee. I continued to run into a strong and icy headwind and my running lacked ease and confidence.” By mile 40 he realized that his chance of even finishing was slipping away, ten minutes behind Hopcroft’s pace. He reached 50 miles in 6:08:06 with a painful knee and a swollen Achilles tendon. At that point he quit in great disappointment. “I felt that I had been cheated as I was still full of pent-up energy and enthusiasm, but once again disaster had struck.” The officials who had organized the event and a big celebration afterwards, were equally disappointed. Mekler would never race 100 miles again.

Recovering from Injury

Serious racing retirement drew near. Mekler explained, “Looking at my running career, I realized that something very basic in my personality prevented me from slowly slipping into the role of an ‘also ran’ and fading away into successive defeats. Either I stayed pretty near the top or I would not compete at all. Entering races as ‘training runs’ was foreign to me. I took every contest seriously, never entering a race without planning for and focusing on either winning the race or breaking the record.” He began to scale back his weekly training miles, relaxed and played more golf.

Fifth Comrades Win

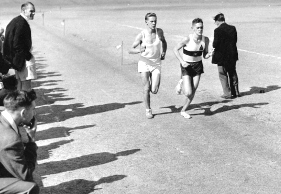

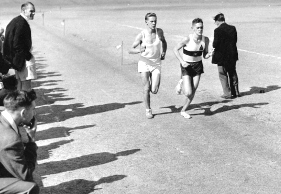

At Comrades, during the second half of the race, Mekler waged a ferocious duel with Tarrant. However, he had heard that Tarrant had dropped out of races before once caught near the late stages. With this in mind, Mekler pushed hard one final time to pass Tarrant and drop him. It worked, and he never saw him again. Another runner crept up on Mekler, but he was able to hold him off and won Comrades for the fifth time in 6:01:11 on the “up” course. Tarrant came in fourth place, with 6:18.

Mekler was thrilled with his win and wrote, “What counted most was that I had won a coveted fifth victory, finally joining the exclusive ranks of my friends Newton and Hayward, as well as Hardy Ballington. It was a tremendous thrill and relief finally to have accomplished this feat!”

Racing Retirement

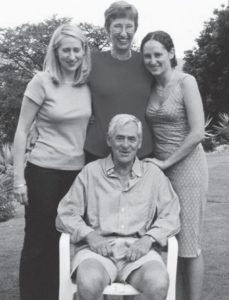

In 1969, after a disappointing third place finish at Comrades because of diarrhea, Mekler went into racing retirement but maintained his close association with the race. He married Margie in 1972, they started a family, he progressed in his printing career to be a managing director, and he took up farming as a hobby for the weekends.

During his running career, Mekler raced in 41 marathons, winning 14, and 32 ultramarathons, winning 13. In addition, he raced in a staggering 403 races under that marathon distance.

In 2017, the Meklers retired, sold their farm, and moved to Cape Town where they could be close to their daughters and grandchildren. In his late 80s, Mekler thought back about his early life in the orphanage. “What would I have done if I hadn’t become a runner or even had I not been sent to an orphanage? I might have gone on to the university. If so, I would have missed out on the exciting life that running has brought me. The influence of orphanage life helped introduce me to running and gave me reason to express a determination that masked my embarrassment at being a product of an orphanage. The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle. The essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.”

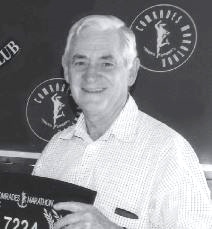

Nine-time Comrades winner, Bruce Fordyce said, “Jackie Mekler was one of the true legends of the race but more importantly in later years, he was an elder statesman of the race, a role he filled with dignity, humility and grace. He was an inspiration to all of us and I am proud to have called him a close friend. Goodbye Jackie Mekler!”

Sources:

- Jackie Mekler, Running Alone: The autobiography of long-distance runner Jackie Mekler

- Jackie Mekler Comrades Speech

- John Cameron-Dow, Comrades Marathon – The Ultimate Human Race

- Tim Noakes. Lore of Running

- Andy Milroy, “The Long Distance Record Book.”

- Bill Jamieson, Just Call Me Wally: Wally Hayward, A Legend in his Lifetime

- Jackie Mekler Comrades Obituary

- com Mekler tribute

- Dave Jack memories of Jackie Mekler

- Evening Standard (London, England), Apr 17, 1954

- The Courier (Waterloo, Iowa), Sep 7, 1954