Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:24 — 36.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

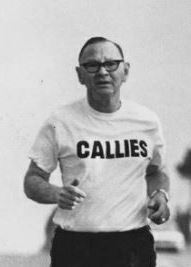

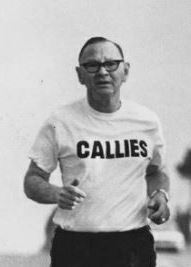

Mavis Hutchison was a pioneer ultrarunner from South Africa who blazed the trail for women runners worldwide. She finished Comrades Marathon (55 miles) eight times in years when very few women ran. She had an impressive ultrarunning career that took her to many countries, and she went on to become one of the most popular women in South Africa.

Childhood

While a teenager, Mavis really wanted to be a good athlete. Her father had been training girls at her school, so she joined in. She said, “I started out full of enthusiasm. I seemed to be getting nowhere fast. I told myself that if I did not have instant success I would never get there. I found excuses to give up. I believe my dad was disappointed, but he never forced me. I restarted a few times but ended the same each time a failure.”

Because of her poor health, her schooling suffered, and she never graduated from high school. World War II arrived, and she worked at the government mint in her hometown making tools for the manufacture of weapons. She wanted to join the Army, but her father would not give consent. He gave her good advice and always emphasized that she needed to be nice to others but should also stand up for herself. He wanted her to work hard but take time to smell the roses. Of her mother, she said, “My mom was a very private person, but some things did rub off and what rubbed off on me most was about going the extra mile, working hard, being not just a starter but a finisher, and being there for one another.”

Troubled Marriage

Mavis sought for more independence and when she was twenty-two, she married a man who turned out to be a heavy drinker bringing misery and abuse into her life. In 1947 she gave birth to twin boys prematurely and one only lived a day. The other son, Jess, was severely disfigured and underwent many operations.

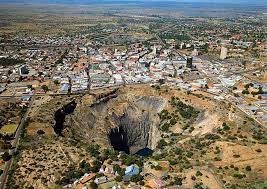

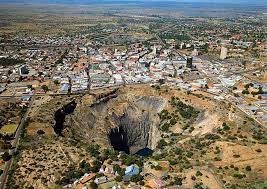

At the age of twenty-four she was worn out mentally and physically, feeling like an old woman. Her husband deserted her by the time she gave birth to another son, Alan, in 1949. She divorced in 1951 and started a new life with her two little boys. After working as a saleslady in Kimberley, she moved to Johannesburg working first for an art dealer and later for record companies. Her family nanny for the past 25 years came along with her and helped raise the boys.

New Life

A few years after moving to Johannesburg, Mavis met and married Ernest “Ernie” John Hutchison (1916-1991) who was a miner. He was a quiet man, but a great stabilizing influence on her and always supportive. After a short courtship they married in 1955. Ernie had two children of his own and adopted Mavis’ sons. Two more daughters arrived, making up a “yours, mine and ours” family of six children.

In 1960, Hutchison’s boys, Jess and Allan got involved in the latest new fad, racewalking. She and Ernie watched them train and compete. Her sons pulled her to be more involved in athletics. As she watched her boys run, she realized she needed some form of exercise and rekindled the desire to become a good athlete.

Early Racewalking

Hutchison said that she began her running career at the age of thirty-seven by chasing after her sons. “Although I was very unsure and nervous at the time, I started training with the boys by running around the local golf course every afternoon. I wanted to be healthier and fitter. With six children, a husband and a home, I realized I had to improve my health and toughen up, or else life would become increasingly miserable.” Her health greatly improved. She started to go on four-mile walks with her sister Ivy and then entered an 8-mile walk race. She eventually attempted her first 50-mile walk in 1962 which she said was a disaster. She quit that day after 16 miles.

Early Running

So, Hutchinson began running. When she started, she felt unsure and did not have any goals in running. She thought that she would never really achieve anything in her lifetime. She began her running on a sand and sawdust track that was used by horses which helped to strengthen her legs. The longest races for women at that time in South Africa was the half-miler. She entered a race feeling confident, went out too fast and finished in the back of the pack. She learned from that perceived failure and started to concentrate more on pacing, learning for others in her club. She started to also get involved in long-distance road running, even though at the time it was considered unwise and unsafe for women. She wanted to run the marathon distance.

First Marathon

Against all odds, she ran in the 1963 Johannesburg Marathon, the only woman among 75 men and the first known woman to run in a marathon race in 37 years. “The officials were not especially enthused but allowed her to run ‘unofficially’ perhaps because a woman who could racewalk 80 km in record time was unlikely to embarrass them by collapsing.”

She explained, “I had to start after the gun had gone off. I had to wait until the runners left, because if I didn’t, I was told that the entire field could be disqualified.”

During the race she received much encouragement from the male runners and from spectators along the flat circular course. The runners were not allowed to take any refreshments for the first ten miles. She ran with ease and finished with a time of 3:50, the second fastest time on record for a woman. She said, “It was so exciting to realize that I had actually finished a marathon.” That was four years before Katherine Switzer’s famed finish at Boston and it was a half hour faster.

For the next few years she was the only woman in South Africa running on the roads. “I was considered a freak! People pitched up at road races just to see me. Running the highways and byways made me a stronger person. It allowed me to cope with what life had to offer. I grew mentally, physically, emotionally and spiritually.”

Comrades

She wrote for permission to run with the support of her own running club. The official reply was “women are not allowed to participate officially in the Comrades Marathon,” but she was permitted to run unofficially and was promised assistance along the road. She trained hard, mostly in the early morning dark or in the evening. Her husband Ernie and son Jess were also entered. At a prerace social she was able to see Comrades great, Wally Hayward.

Sleeping the night before the race did not come easily because of nerves and worry about the rain that was falling. She got up early and jogged to City Hall for the start with nearly 400 runners. She was thrilled to be the only woman in the field but had doubts whether she would succeed. Rain started before the start and continued on throughout the race.

Hutchison, at the age of forty, became the third woman to finish in the history of that race with a time of 10:07. She was so excited to have finished within the official cutoff time. But the experience in the rain was pretty miserable and she said, “never again.” But as a typical ultrarunner, she changed her mind once the pain went away and continued on.

It was disappointing to not receive a finisher medal as all the men did. “I trained as hard as anyone else that was in the race, probably twice as hard and did not receive any recognition at the finish.” (Years later Comrades gave her the medal). She went on to finish Comrades seven more times and every year was joined by more women. Ten years after her first Comrades, women were finally allowed to enter officially.

Throughout the 1960s, Hutchison continued to run in cross-country events even though they were too short for her. She helped younger women succeed and was considered a pioneer in the early days of women’s cross-country. She led a team that traveled to compete in the United Kingdom. At some events men’s teams threatened to boycott if women ran and at an event in Scotland, the women’s team was sadly banned from running.

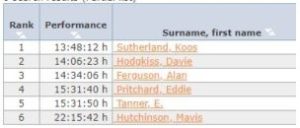

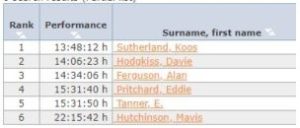

1971 Johannesburg 24 Hour Track Race

Hutchison wanted to compete over very long distances on the road. Comrades was too short to bring out the best in her. By 1971, at the age of forty-six, she was ready for a greater challenge – a 24-hour race on a track at Hector Norris Park in Johannesburg. She put in three months of intensive training including hours after work and eight hours a day on weekends, mostly on a track. She explained, “I sometimes did a bit of road work, but people passed remarks and some men even tried to pick me up, until they saw my gray hair.”

By 21.5 hours, her crew realized that she could break the 100-mile time set by Geraldine Watson back in 1934 of 22:22:00. Hutchison gritted her teeth for the final laps and reached 100 miles in 22:15:42 which she thought was a “world record.” However, her time was far off Nancy Cullimore’s 100-mile road time of 16:11:00 set earlier that year in America, that they certainly did not know about. (See episode 64).

But Hutchison wasn’t finished, she intended to claim the world record for 24 hours. When the clock reached that point, she had covered 106 miles, 736 yards, indeed a new world best. She commented, “Surprisingly, afterwards I did not feel exhausted, though the tops of my legs were sore. They put a laurel wreath around my neck. There were a few damp eyes while this was being done.” An ambulance crew rushed onto the track with a stretcher expecting her to pass out at any moment. She did not. Of the fifty-one men who started, only twenty finished.

Quest to Run in the Classics

Next Hutchison wanted to run in the classic ultras of the time, London to Brighton (52 miles) and Two Bridges in Scotland (36 miles). Her dreams were dashed when she was informed that women could not run officially in those races but could start an hour after the men so as not to confuse spectators that she was really part of the race. She could not accept those discriminatory terms and was very disappointed not to compete in these DeFacto world championship ultras.

1973 Germiston 24-hour Walk

In 1973, Hutchison entered the first 24-hour walk ever held in South Africa. She trained for the race by walking about six hours each day. The event was held on July 8, 1973, at Germiston’s Delville track in front of a large crowd. Her family again crewed for her along with legendary Wally Hayward.

“As Mavis relentlessly strode around the track, and the sun sank below the horizon, the temperature that winter’s night dropped well below freezing, but she was set on giving her utmost.” A shoelace was too tight and ended up causing painful tendonitis after six hours, but she pushed on. Smoke from fires keeping crews warm during the frigid night also affect her. She successfully reached 100 miles in 23:48.

1973 374-Mile Run from Johannesburg to Durban

Hutchison had dreamed for three years of doing a multiday run of about 374 miles over the Drakensberg mountains from Johannesburg to Durban on the coast. Several men had accomplished this grueling run. It would be much further than any woman had been known to run. On October 14, 1973, shortly after 4 a.m., Hutchison started her historic run to the cheers of an enthusiast crowd. She said, “As with all great challenges, doubts and misgivings fed my apprehension. Had I been too ambitious this time?” Many of her clubmates ran with her through the streets of Germiston. Also running with her was John Ball of England, who held the fastest known time for the run. Wally Hayward also was on hand. She was officially a big deal in South Africa.

She reported, “My progress was very slow indeed. I just could not move forward at any reasonable pace and felt most annoyed and disappointed. At about 4:30 that afternoon it was decided to call it a day after 73 kilometers.”

The next day there was again a major struggle in nearly hurricane force winds of 70 mph. Her optimism waned and she wondered if she would have to quit soon. “I was so exhausted from the wind and the rain. It actually ripped my waterproof jacket to ribbons.”

After dinner that day she collapsed from exhaustion. Her trainer suggested that she quit, but she was determined to carry on. Each day she courageously continued. Truck drivers on the road recognized her, honking, and waving as they passed. She even received a kind escort from the local Traffic Department.

On the fifth day she decided to run through the night, going for twenty-seven straight hours with pacers taking turns to help her. “I will never forget the 27 hours I had them constantly at my side, providing vital encouragement during this long stint. Two of them ran on either side of me; one to protect me from the on-coming traffic and the other to protect me from stepping off the edge of the road, which at times was quite a hazard, especially as it grew darker.”

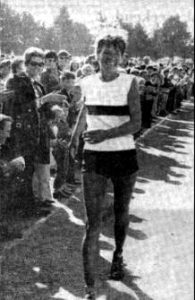

After 6 days, 13 hours, and 55 minutes she reached the finish at Durban City Hall where she was greeted by 3,000 cheering fans. They sang, “For She’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Tears of appreciation poured down her cheeks as she felt the crowd’s warmth and love. A garland of flowers was put on her. Her mother was there and commented to a reporter, “She’s always been a little crazy.”

Other Multi-day runs

The next year she attempted to repeat the run, but this time in the much more difficult uphill direction during the winter. She beat the fastest known time. A police escort rallied around her as she finished in Germiston on June 10, 1974. “If the down run was seen as an unusual accomplishment, the more difficult up-run was unthinkable. Yet Mavis was terribly disappointed not to have met the schedule she’d set. ‘I hoped to be here a day earlier.’” A newspaper article called her “the woman who doesn’t know what it means to give up.”

As early as 1973, Hutchison dreamed of running across America, but because of the extreme cost, she knew that she needed to start attracting sponsors. In 1975, backed by a popular soft drink, risking her amateur status, she ran 1,000 miles from Pretoria to Cape Town. She finished that amazing run in 22 days, four hours, averaging about 44 miles per day.

That year, 1975, women were finally allowed to officially run Comrades. Not yet recovered from her 1,000-mile run, she desperately tried to run but had to drop out for the first time.

In 1976 she ran about 915 miles from Germiston to Cape Town in what she called “the worst experience of my career. The road was so bad with rocks and pouring rain.” She pushed through injury, determined to finish, and reached Cape Town in 19 days and 50 minutes, averaging about 48 miles per day.

Hutchison’s amazing ultra accomplishments attracted a sponsor, Vanda Cosmetics, who agreed to fund her run across America scheduled for 1978. To prepare, in 1977, she ran across South Africa north to south in seven and a half days, for about 340 miles in rainy weather.

Early Runs Across America

Who was the first known woman to cross the continent on foot? In 1890-91, Zoe Gayton, a famous actress, claimed she walked from San Francisco to New York City in 184 total days, with 148 walking days. (See episode 24). Analysis of the evidence left behind has shown that her walk was likely legitimate, and she may have been the first.

The woman usually credited for the first transcontinental run is Barbara Moore, a Russian immigrant to Great Britain, who went from San Francisco to New York City in 1960 in 85.35 days. However, she received a car ride for 5.5 miles which she “made up” near the finish in Central Park. By 1978, there had been at least 99 transcontinental walks/runs that were considered legitimate with the fastest known time of 52.82 days by ultrarunner Tom McGrath, a bartender from New York City. He went from New York City to San Francisco.

1978 Run Across America

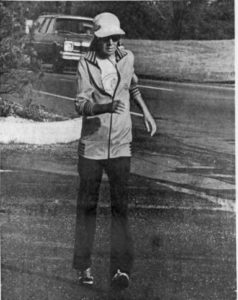

The traffic on the roads she ran on was often terrifying. She said, “I never took my eyes off the cars and trucks. It was the traffic from behind that scared me half to death. At times they would be so close that I could touch them. The heavy trucks drawing trailers would lift me up as they passed and I would always land on my right leg.” Passing motorists would constantly stop thinking that she needed a ride out in the middle of nowhere.

important thing for me personally is I’m actually doing it right now.” She was particularly proud that age was not a barrier for her.

Hutchison took a southern route during March and April through California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma. In total she crossed thirteen states. Her support crew scouted out the best routes, handed out press releases, shopped, cooked, and kept the budget for the trip. They usually spent nights in campgrounds but occasionally splurged and stayed in motels. She generally began her run each day at 4 a.m., stopped for tea around 7 a.m., and took quick naps during the morning and afternoon. Her average pace was 20-minute miles and she averaged forty-five miles per day.

Her scariest experience was in the Midwest. “Running across the MacArthur Rail Bridge in St. Louis was terrifying. It was so high and narrow, and I kept my eyes closed nearly all the way across.”

When asked about her impression of America she said, “The traffic in America is absolutely non-stop. It keeps going 24 hours.” During one stretch cars were whizzing past her every seven seconds. Throughout the entire trip, she took only one day off, day thirty-three when she suffered from shin splints. She said of the journey, “There were times that I was not sure I would get to the end of the day, let alone the end of the week! Sometimes even the next hour was not a certainty.”

Hutchison met the missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints just before she left for the United States and asked them to come back. They did on her return to South Africa and she was baptized into the Church on September 30, 1978.

John O’Groats to Land’s End

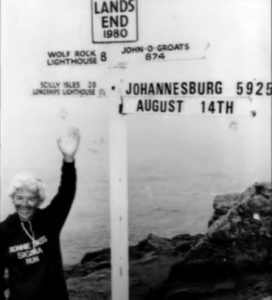

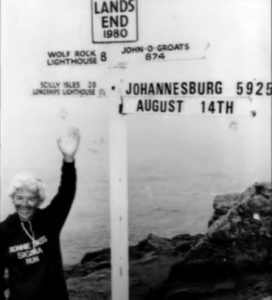

Hutchison eventually wanted to have another adventure after achieving her life-long goal. She chose to go after the John O’Groats to Land’s End fastest known time, running the length of Britain, a distance of about 874 miles. In July 1980 at the age of fifty-five, she traveled to Great Britain for the mid-summer attempt, announcing that she intended to beat the 17-day record by two days.

On the day Hutchison started from John O’Groats, Scotland, she was surprised that others were starting their attempts including some attempting to push wheelbarrows the entire way. Nearly every day there was another person making the pilgrimage.

As the end came closer, she put in a couple all-nighters, 20-hour efforts. Eventually she could no longer run but continued to walk forward. With only twenty-five miles to go, it was written, “There are already signs of jubilation in the growing caravan camp that is following her. They are sure Mavis is going to do it. She says very little herself but presses on with relentless determination. There are no moans from her.”

She told reporters on her arrival that she was finished with marathon running and would instead take up sprinting. News of her accomplishment was printed in newspapers across America. The BBC called here “the toughest grandmother in the world.”

Banned from Amateur Athletics

But even while barred, she continued to run. In 1982, at the age of 57, she accomplished an amazing 2,000-mile charity run in 58 days. In 1985 at the age of sixty-one, she accomplished a 930-mile run to fight drug abuse. She was recognized as being one of the most popular women in South Africa.

International Masters World Games

On May 19, 2022, Mavis Hutchison died at the age of 97.

The Comrades Marathon (about 55 miles), held in South Africa, is the world’s largest and oldest ultramarathon race that is still held today with fields that have topped 23,000 runners. The year 2021, marked the 100th anniversary of Comrades Marathon.

This episode on Marvis Hutchison is the fourth part of a series honoring Comrades and South African ultrarunning.

- 80: Comrades Marathon – 100 years old

- 83: Hardy Ballington – The Forgotten Great Ultrarunner

- 84: Wally Hayward (1908-2006) – South African Legend

- 85: Mavis Hutchison (1924-2022) – Galloping Granny

- 86: Jackie Mekler (1932-2019) – Comrades Legend

Sources:

- Dave & Gillene Laney, Unstoppable Woman: The Forgotten Story of Mavis Hutchison — First Woman to Run Across America

- E. Dale LeBaron, Three Thousand Mile Lady

- Mavis Hutchison Blog

- usacrossers.com

- Talk Ultra Podcast, episode 20

- LimeGong – Mavis Hutchinson

- Modern Athlete, Nov 1, 2010, “She is still…the Galloping Granny!”

- Des Moines Tribune (Iowa), Mar 2, 1978

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Mar 4, 1978

- The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey), May 19, 1978

- The Daily Breeze (Torrance, California), May 21, 1978

- Daily News (New York, New York), May 21, 1978

- Newcastle Journal, July 26, 1980

- Aberdeen Press and Journal, Sep 24, 1980

- The Jackson Sun (Tennessee), Aug 15, 1980

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Aug 15, 1980