Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 29:40 — 34.7MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

Spartathlon, an ultra of 246 km (153 miles), takes place each September in Greece, running from Athens to Sparta and with its 36-hour cutoff. It is one of the toughest ultramarathons to finish.

In Part 1 of this series, episode 88, the story was told how Spartathlon was born in 1982, the brainchild of an officer in the Royal Air Force, John Foden. Three servicemen successfully covered a route that was believed to have been taken in 490 B.C., by the Greek messenger, Pheidippides. The 1982 trial run set the stage for the establishment of the Spartathlon race. The race’s 1983 inaugural year is covered in this part won by Yiannis Kouros of Greece.

| There are now ten books in the Ultrarunning History series by Davy Crockett, available on Amazon. https://ultrarunninghistory.com/urhseries/

|

The Founding of Spartathlon in 1983

After John Foden and two others finished the historic 1982 trial run between Athens and Sparta, Foden told those at the finish, “You need to make the route we have run, a race.” However, he did not think seriously that a race would be organized anytime soon. Michael Graham Callaghan (1945-2013), an Athens businessman, and a member of the British Hellenic Chamber of Commerce (BHCC) in Greece was the driving force and the founder of the formal Spartathon race.

Back in 1982, Callaghan had helped Foden organize his trial run and obtained sponsors. Callaghan was at the finish in Sparta and awarded the three finishers crowns of olive leaves. A month later, Callaghan received a kind letter from Air Marshal Thomas Kennedy from the Royal Air Force (RAF) in Germany, thanking him for his support of Foden’s 1982 RAF expedition run from Athens to Sparta.

Plans for Spartathlon come together

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A multi-national team of supporters came together led by Callaghan and was based at the British Hellenic Chamber of Commerce in Athens. Under Greek law, Callaghan was not allowed to be the actual president of the organization, but he was the first race organizer. Foden said, “My idea to have a race would never have taken off if were not for Callaghan’s energy, enthusiasm and talents as a salesman. At the start he might not have known much about running and relied on the advice I gave him during visits to Greece, but he soon became very knowledgeable.” A group of Athens-based British businessmen were signed up to be the main sponsors for the 1983 race.

Entrants

Yiannis Kouros

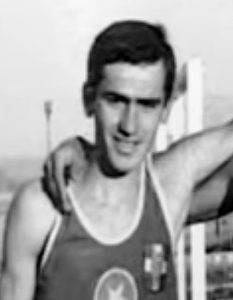

At the age of sixteen, he began formal athletic training and started running races. At first his coach dismissed Kouros as being “a mediocre athlete who just didn’t have the build to go fast.” But he progressed to be one of the top high school runners in Greece. He was a junior champion at the 3,000 and 5,000 meter distances.

In 1977 at that age of twenty-one, Kouros ran his first marathon in 2:43:15. His times continued to improve to 2:25 in 1981. Soon he discovered that he excelled far more at ultra distances. In 1981 he worked as a guard at an athletic stadium. In found time to train about twice per day. By the end of the year, he asked the Sports Council to send judges to witness his attempt to run 100k, running on a 20k road course, seeking to set a national record. He finished in 7:35 but no judges came.

By 1983, the year of the first Spartathlon, Kouros, age 27, had finished 25 marathons, but he was not well-known outside of Athens, Greece, certainly not known internationally among ultrarunners. He said, “I read about a race from Athens to Sparta. I wanted to sign up. I had confidence I would complete the race and that I would probably be the first Greek to finish.”

“I knew part of the course, especially the last third of it. I made a plan that I should cover it between 21 and 22 hours. But I thought that those experienced runners who had also world records and great performances should finish in less time. I never thought it would be easy. In contrary, I considered it heroically.”

Eleanor Adams

Adams then gave up running for the next eight years and had three children. In 1978, at the age of thirty-one, she took up jogging again to try to regain some fitness. Adams first marathon came in 1980, the People’s Marathon at Solihull, England, where she finished second with 3:26:41. She soon broke three hours routinely.

Adams said, “I never had heard of ultrarunning at the time in the early 80s. I was focusing on being a marathon runner because women were just starting to be accepted in running marathons.” A British women marathon squad was established with the top ten women marathon runners and Adams was ranked 12th. Her primary goal was to make that squad.

One weekend she was intending to run a marathon at Leicester. She noticed in the newspaper that there was going to be a 12-hour event at Nottingham. Her three children were small and she thought they could play in the infield as she ran. So, she and two other teammates went to the 12-hour race. She intended on only running the marathon distance, but things went so well that she kept going.

Adams heard about Spartathlon from Malcolm Campbell (1934-), an experienced ultrarunner and an influential British running administrator, who offered to arrange for her travel to the race with a large contingent of the top British ultrarunners. She recalled, “There was a race across the across the mountains in Greece called, Spartathlon, Athens to Sparta. I knew all about Athens to Sparta. I used to teach history for a time. So, I knew the historic aspect of it. The whole thing sounded really interesting and fun.”

Adams had difficulty being allowed to run in the inaugural race because she was a woman. She explained, “Because the race was based on a historical military event, the race officials were very much against having a female competitor and it was only due to the intervention of male ultrarunners that I was allowed to compete. I didn’t know until the very last minute that I would be going to Greece. I did no specific preparation for the event.”

Still an ultrarunning rookie, Adams said, “I had no idea what I was doing. The whole thing was hugely exciting, and I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I knew there was a big hill to go up and down, but other than that I was in very much ignorance of anything. The buildup to the race was great because we were there a few days before. There was quite a lot of hype connected with it. There were quite stringent cutoffs. I was the only lady taking part.”

Finally in Greece, on the bus previewing the course and sight-seeing, she said, “It’s going over that mountain in the dark that worries me a little. It’s a tiring course for someone who’s only run round and round a track. It will be a real challenge.”

Dusan Mravlie

Mravlie took up ultrarunning in 1979, running in several of the massive 100 km races and gained experience going over 100 miles by reaching 128 miles in a 1983 24-hour race in Czechoslovakia. He signed up for Spartathlon, confident that he would do well.

He said, “I am a fanatical long-distance runner, so you can imagine how excited I am at the thought of taking part in this spectacular historical event, especially because this is the first time it is being held.”

Patrick Macke

For several years he preferred the marathon and 50K distances as opposed to the longer ultras. Spartathlon would be his first time going after big miles, starting his life-time association with with the race. That first year he just hoped to finish and planned to run the entire way with Edgar Patterman(1934-) of Austria.

Ed Dodd

Dodd was invited to run at Spartathlon by Dan Brannen. “The only reason I went, was that my way was paid. There was no way with three little kids and a high school salary that I could afford to fly to Greece and spend a week away from my job to run a race. Dan Brannen called me up and said he had been asked to go but he couldn’t. The woman who was funding the trip was willing to send anyone he recommended. She was an American woman married to a Greek Naval officer. I said ‘sure I’ll go’ and she made all the arrangements.”

Marvin Skagerberg

Marvin Skagerberg (1938-) of New York City was another American in the field. He had accomplished running 405.5 miles at a six-day race earlier in the year. He said, “The interesting thing about Spartathlon is definitely the historic angle and of course it’s a multi-day race which is growing increasingly popular in the United States.” John Wallis, 46, of Michigan was the third American. He was a very experience ultrarunner and had about ten 100-milers to his name.

On the preview bus ride, Dodd and Skagerberg said, “I’m just intrigued with the opportunity of running in the footsteps of such an historical figure as Pheidippides.” “I think most of us couldn’t resist running the Spartathlon because we would be sharing a course that was run by another human being 2,500 years ago.”

Other Runners

John McCarthy, one of the original three runners from the 1982 trial run came back to run again. John Foden was also there but not running. McCarthy said, “Because I have done it once already, I found I had to come back and do it again. We are hoping that it will become a regular event. I’m as terrified now as I was last year. It is a daunting task, but I think I can do it.”

A Greek runner said, “I first admired Pheidippides when I was a schoolboy. I’m very lucky to be here in Athens to run in this event. Besides, I like to meet foreigners and make friends in the spirit of friendship and peace. I am a fanatical long-distance runner, so you can imagine how excited I am to being able to take part in this spectacular historic event, especially because it is the first time it is being held.”

The Start

Athens to Corinth

At the 31 km mark Mravlie was in leading followed by Alan Fairbrother, 27, of Great Britain and Yiannis Kouros, 27 of Greece. The rest of the field had become widely separated. Kouros surprisingly took the lead at 34 km. He reached 71 km (44 miles) in five hours.

Corinth to the Mountain

The first cutoff point was at about mile 52 after the Corinth Canal. Runners needed to arrive there by 6 p.m., eleven hours. When Kouros crossed over Corinth Canal, he did so about two hours before the most optimistic estimate by race organizers. Many of the runners did not make this cutoff either because of lack of training or because of the stifling heat.

After Corinth, Kouros became upset because he thought the course was not following the route Phiedippidis took. He said, “I got annoyed and started shouting when after Corinth we headed to the right (northbound). When Phiedippidis reached the Isthmas, he knew Sparta was to the south, the man was in a hurry.” Clearly, he disagreed with the route that John Foden had researched that tried to use ancient military routes. Kouros continued, “I had strange feelings about the falsification of the history that was taking place once again in my country and at the same time, I had to work hard to find thoughts to make me keep going.”

After eight hours and about 56 miles, Kouros held a 3 km lead over Mravlie. Fairbrother was still in 3rd, several more kilometers back.

By late afternoon, Macke, Adams and Dodd were about 30 km behind the leader, Kouros. They passed by ancient Corinth as the sun was going down.

During the evening, children would come running out of each little village to greet the runners. American John Wallis would teach them how to high-five as he ran by. They would then run into the village and see all the citizens out in front of the taverna cheering them on. After midnight, the villages were sleeping, but still there were always three or four volunteers maintaining the aid stations and checkpoints.

After dark, disaster struck Dodd’s race. “During the night, my light went out. A Greek runner came up on me. I didn’t speak Greek and he didn’t speak English. I somehow told him that the battery had gone out. He had someone helping him. We got to a town and they went into store with me and we bought batteries for my headlamp. I don’t know what I would have done with that because he was going faster that I was and couldn’t hold him up.”

Out in the dark there were eerie sounds. “Once it got dark it was a little eerie running down this dirt road in a foreign country hearing these howlings going on off in the dark. Barking animals. I don’t know if they were dogs. I had never run a true trail race before. I was a track and road person, so this was very unusual to me.”

Adams commented, “When we got to the mountain it was dark and we had a guide to take us up and over. It was quite surreal looking back down the mountain seeing all these little twinkling lights because we had to carry torches.” Dodd added, “On the mountain, I knew I was running short on time. They had people situated at various locations, I guess to point us in the right direction. It wasn’t a very difficult mountain, but I got to it in the middle of the night.” Skagerberg said the final ascent of the mountain was steeper than the last mile up Pikes Peak, though the descent down the other side was easier.

Adams remembered that there were no course markings, but Dodd said that it wasn’t possible to get lost, certainly not on the mountain. He never had any anxiety when he came to a turn because of the number of helpers. Dodd made it to the top and then started his run down. “When I came off the mountain, I said if I don’t really run, I’m not going to make the 105-mile cutoff. So the last five miles down the mountain I ran it like a cross country race which was a big mistake. By the time I reached the checkpoint, I was pretty whooped.”

From the Mountain to Sparta

Many hours later as Dodd was making his way over the Mountain, he came across fellow American Marvin Skagerberg. Dodd said, “I remember going through a small town late at night, and he was lying on a bench. I asked him how he was feeling and he said, ‘Not too well.’ I kept going. We both made it over the mountain. We had to be at the Nestani (mile 107) checkpoint by 24 hours. I got there about 24:05. I sat down all dirty from the mountain, washing my legs off. Marvin came in and sat down next to me.”

Skagerberg recalled, “At 7:04 a.m., I screamed a very bad word at the gorgeous Greek countryside. Three-quarters of a mile short of the 24-hour elimination point, I ground to a halt and walked slowly in. I was doubly disappointed to see Ed Dodd a quarter mile ahead, also eliminated by just a few minutes.” The third American Wallis had packed it in a few kilometers earlier when he saw that it would be impossible for him to make the cutoff.

But Dodd explained, “The official came up and said, ‘You two are the last two over the mountain. Even though you missed the cutoff we will let you keep going.’ Marvin said, ‘That’s OK, I’ll stop.’ I said, ‘Oh great, I’ll keep going.’ That was a dumb thing to do. So I got up and kept going. Within ten kilometers I was shot. I just sat down in an olive orchard and waited for someone to pick me up and take me to the finish in Sparta.” Dodd was totally out of fuel and badly dehydrated with no crew. He made it to about 112 miles (180 km).

Skagerberg had a theory about their DNF. “We three Americans had probably eliminated ourselves with a tactical error. We had run the first 50-mile sector very slowly, between 9:40-9:55, assuring that we came through the 85 degrees day fresh and ready for a good run all night. But the next 55 miles were more difficult than we had anticipated, steep and rough dirt tracks that slowed us and kept us in time trouble.”

Adams kept plugging along. She saw a mountain wolf at dawn. “I was always attracted to doing things that were difficult. Ultras were made for me in many ways. But in a lot of ways they weren’t. I was very good at sleeping and I was absolutely hopeless in eating. I suppose mentally I had the toughness, drive, and focus. The mental attribute were all there.”

The Finish

It was reported, “At a quarter to five in the morning, Kouros was only one kilometer from the statue of Leonidas. Leading towns people, race officials, and a few citizens of Sparta were waiting at that early hour to greet the seemingly tireless Greek runner, a 20th century Pheidippides.” Irene Watson heading up the race headquarters in Athens reported, “On of our team was placed behind the statue with an open land line and she excitedly reported as Yiannis was approaching until he touched the statue of Leonidas.”

Adams passed Macke coming down the hill into Sparta. He was having great difficulty. The British runners who had previously DNFed came along the last stretch to give out bottles of water to the Brits still running. Adams finished in 32:37:52 and Macke finished in 32:55:51. Adams said, “I finished in a dreadful state. I wore a pair of what would have been trail shoes at that time. But of course there was a lot of road. The first 50 mile were all on pavement. Wearing trail shoes was not great on the feet.” Macke was thrilled with the experience in Greece. He said, “This event is much more than just a race.” There were fifteen finishers. (For some reason, in later years an inaccurate finish list was created that included others.).

The Awards

Skeptics

Skagerberg was still thinking of the Kouros victory on the flight home. He wrote, “After I settled in my seat, I thought about the race. There had been a lead vehicle, and also a supply truck on which we had left some supplies for the night as there were no drop bags. The truck had been pulled to the front and was never seen by us slower runners. ‘Wait,’ I said to myself, “the lead vehicle and the truck was with the front runners for the whole time, and the officials were British! How could Yiannis have cheated?” I was a Yiannis supporter from then on.” Irene Watson who headed up the race headquarters said, “Yiannis was tracked throughout. We all knew he was not cheating.”

A few months later, Kouros was invited to run in a three-day 200-mile stage race across Austria. They had a car with him the entire time and Dan Brannen was there to witness. He crushed the field again. Kouros was never seen walking, even while passing through 30 aid stations. His slowest mile during the three days was faster than eight minutes. He won by more than three hours, even with taking a wrong 3 km turn that cost him about 20 minutes. After that race, the ultrarunning community started to believe that he was the real deal. Kouros would return to Spartathlon the next year and truly make history.

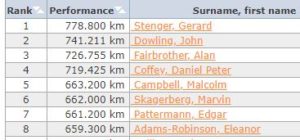

Both Yiannis Kouros and Eleanor Adams (now Robinson) have both been recognized by many ultrarunning historians as being the greatest ultrarunners of all time.

Sources

- Spartathlon – British Spartathlon Team

- Spartathlon – historisk aspekt

- RAF Exppedition – John Foden

- In the Footsteps of Pheidippides (1st Spartathlon – 1983)

- Yiannis Kouros 1983 Spartathlon Finish

- Eleanor Robinson results

- Legends of Spartathlon – Episode 8 – Eleanor Robinson

- Katie Holmes email, Oct 24, 2022

- Interview with Ed Dodd, Oct 4, 2021

- Johnson City Press (Tennessee), Sep 29, 1983

- The Billing Gazette (Montana), Sep 30, 1983

- Tallahassee Democrat (Florida), Oct 2, 1983

- Ultrarunning Magazine, Sep 1982, Dec 1983

- Comments by Irene Watson, Oct 9, 2021