Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:30 — 31.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

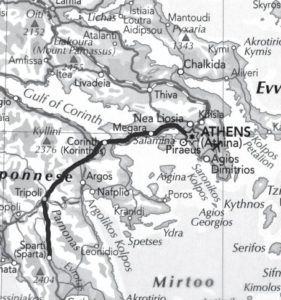

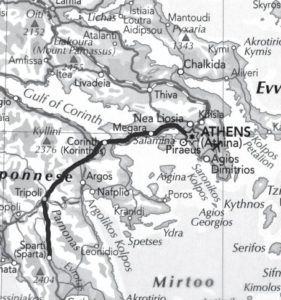

Spartathlon is one of the most prestigious ultramarathons in the world. It is a race of about 246 km (153 miles), that takes place each September in Greece, running from Athens to Sparta on a highly significant route in world history. It attracts many of the greatest ultrarunners in the world.

This is part one of a series on the history of Spartathlon. In this episode, we will cover how Spartathlon was born, a story that has never been fully told until now. It was the brainchild of an officer in the Royal Air Force, John Foden.

| Help is needed to continue the Ultrarunning History Podcast and website. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

Pheidippides’ Historic Run

In 490 B.C., one of the most famous battles in world history was held between the Athenians and the Persians who invaded what we now call Greece, landing at Marathon. Before that battle, a professional messenger named Pheidippides was sent by Athenian generals to Sparta, with an urgent message to ask for reinforcements against the much larger Persian incursion.

John Foden

Over the years, the Foden family would make multiple long sea voyages to Great Britain to visit family in England and Scotland. At the age of seven, John travelled to and from England by steam ship with his mother, his three-year-old sister, Pauline Margaret Foden, and his uncle, James Shields Boyd.

Foden Takes Up Running

In 1978, Foden was studying for an advanced degree at a university. As part of an assignment, he read about the story of Pheidippides’ run from Athens to Sparta as recorded by Greek historian Herodotus. He read in that history, “Pheidippides was sent by the Athenian generals, and, according to his own account . . . reached Sparta on the very next day.” As a long-distance runner, that caught Foden’s attention. He wondered if the story was true. Herodotus had been criticized for in inclusion of legends and fanciful accounts in his work. A fellow historian accused him of making up stories for entertainment. But many of his tales had been confirmed by modern historians and archaeologists. Foden wondered if Pheidippides’ run was truth or an impossibility as so many had suspected.

In the meantime, Foden continued to go further and faster. In 1980, at the age of 54, he won a silver medal at the World Masters Athletic Championships in New Zealand.

Foden Begins Ultrarunning

By 1981, Foden was stationed in Germany and began running ultradistances in races around Europe. He ran in the Lauf Unna 100 km in Germany, finished 26th out of 554 finishers, in 9:03:49.

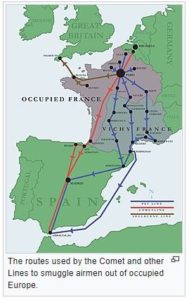

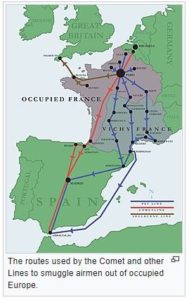

The 1982 relay that Foden participated in was designed to raise funds for the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society that aided families of continental civilians who gave their lives in helping British fliers escape from the Nazis. The run was organized as a relay of eight airmen from four countries. Each ran 10 km legs over the nine days. Foden remembered, “We met so many interesting people down the route and there were some phenomenal coincidences with those we met.” They received a marvelous reception from people along the way that moved them to tears. This experience certainly must have further sparked his interest in recreating the run made by Pheidippides in Greece.

Also in 1981, Foden ran in the World Championship Marathon Christchurch and had a podium finish. Early in 1982, he ran 100 miles in 31 hours at the Pilgrims Race in Britain.

Plans for the 1982 RAF Expedition.

It was reported, “Foden conceived the idea of repeating the ancient run, an attempt which as far as the Greek athletic authorities were aware had not been tried during the past 2,400 years.” When asked why he was doing the run, Foden in later years admitted, “I wanted to be famous, the man who proved an important piece of history was correct.”

Foden recruited four other marathon runners in the RAF that were stationed in Germany to join him in the run. Two were from Scotland and the other two from England and Australia. He also recruited six other RAF servicemen to serve as a support crew. All six had marathon experience and included a medical attendant and a cook. A date in October 1982 was chosen and travel with the RAF was arranged. That month was important because it was believed the the battle of Marathon occurred anciently in the Fall. Unfortunately, their flights From Germany to Athens were cancelled indefinitely so he had to rent two “minibuses” (vans) for the trip.

Foden’s wife declined the invitation to go with him to Greece. “My wife thought I was mad. She thought the whole thing was ridiculous and didn’t want to encourage me.”

It was a long and difficult trip that passed through Communist-occupied Yugoslavia. They had hoped to get to Greece sooner, in order to scout out the route carefully, but they only had a week to prepare. Before he left Germany, Foden was able to get an air navigation map that included Greece, but it was still too small of scale, so he had to adapt and propose a route in the days leading up to the run.

The First Five Runners

The five runners who took part in the historic 1982 run in Greece were:

- Ted Marsh, age 47, was a Warrant Officer.

- John Harold Scholtens, age 27, primarily stationed in Lossiemouth, Scotland. He was a flight Lieutenant and served as a “Buccaneer navigator.”

- John Foden, age 56, was a Wing Commander stationed in Germany. He was oldest, but also the most experience runner in that group, and in charge of the route.

- Norman Niblock was an Air Electronics Operator also primarily stationed in Lossiemouth, Scotland, who described himself as “a young 43.”

- John McCarthy, age 40, was a Flight Sergeant. He already had some ultrarunning experience. He ran in the 1982 Vogelgrun 100 km in France and finished 32nd out of 65 runners with a time of 10:11:31.

Crew from Campion School in Athens

Campion was an English-language international school with a British curriculum adapted to make full use of the location and culture of Greece. It was established in 1970. There was a wide range of competitive sports to offer at the school, including cross-country running. It was hoped to find runners and guides familiar with the country who could lend valuable support along the way.

A team of six from the school volunteered to be part of the adventure, including four teachers and two students. The teachers were Phil Simmonds (art teacher), Dave Ireland (the school team organizer), Rob Biggs, and Andy Birch. The two students were Nick Papageorge (age 18), and Ian Katsivalis (age 16). The four teachers did not speak Greek, but the two students did.

Nick Papageorge

The Start

On October 8, 1982, Foden, age 56, and the other RAF officers started out at Athens at dawn, at 7 a.m. They began their run at the edge of the ancient Agora marketplace that lies beneath the Temple of Hephaestus. Anciently, this marketplace was the primary meeting ground for Athenians, where business was conducted, a place to hang out, watch performers, and listen to famous philosophers.

It was reported, “Five marathon runners from the Royal Air Force have set off from the ancient Agora beneath the Acropolis to retrace Pheidippides’ steps.” The goal was to finish in less than 36 hours. Foden said, “It was really a test initially because I didn’t know if I could do it. I was very uncertain, but I was determined to do it.”

Foden recalled, “Once I started running, I had to forget about everything else and concentrate on one thing alone, and that was to get to Sparta.”

The First Day

The RAF crew of six, in two vans. tried to follow along on nearby roads. “To make sure that the team does not die of hunger or thirst, Sergeant Harry Killeen has established a series of refreshment stations along the route. The runners will be given a hot meal of pasta or rice every 32 miles.” They also fed on military meals ready to eat along the way.

Foden explained that their main problem during the first stretch was the heat. The runners had hoped to acclimatize to the hotter Greece weather, but their one week in Greece had had been untypically cool weather.

“The five runners initially stuck together, trying to protect one another and covering each other’s backs.” Later, they became split up and ran at their own paces, making things more difficult for the support crew. Marsh, ahead, had no food all the way to the Corinth Canal (about mile 52), so he had to buy some from a shop. “John McCarthy was so thirsty at Zevgolation, he tried to drink from a tap at a petrol station. But the owner set his dogs on John to chase him away.”

Niblock dropped out early before Corinth (about 85 km/52 miles) because an old knee injury was giving him pain.

The Campion School Crew Joins In

It wasn’t until later in the day that the six helpers from Campion School joined in. The teachers brought two cars they owned to make the rugged trip, two very old Mercedes. Papageorge explained, “We heard that the runners had started at 7 o’clock in the morning, outside of Athens, just as the sun was rising below the Acropolis. After school, we met up with them about 4 p.m., just past Corinth, about the 80 km mark, at the Corinth Hellas Can Factory.”

Papageorge initially paced Marsh during the early evening. They plodded along and talking about many things along the way. But Marsh gave up about 40 km later near Nemea because of a bad sunburn. He also knew that he had gone out too fast and was very disappointed. Marsh and Papageorge jumped into the car driven by one of the teachers.

Things were confusing as the runners were spread out, supported by the four vehicles that would go ahead, wait, and at times go back looking from them. Papageorge recalled, “There weren’t any check points. The RAF expedition was pretty badly planned for an RAF expedition.”

Running Through the Night

Papageorge recalled, “I remember running a long way with him, going through some valleys. At one point, we were running through a field trying to go more or less in the right direction. We stopped at some point to stop to eat and drink, and then we heard some local hunters shooting out in the dark. We thought that they were shooting at us. We ended up legging it across this field and getting to the bushes on the other side, getting back onto the road, and continuing on.” They caught up with the car and Papageorge traded off pacing duties with someone else.

Foden remembered, “Navigating at night and in the gray murk of dawn was tricky. Complicating matters, radio contact between the two support vehicles was lost in the mountains, and their ability to communicate with each other was severed.”

Up over the Mountain

Papageorge, in Birch’s old Mercedes. pushed up the mountain on steep and rough switch-back roads. “We drove up quite far. It was a full moon, and we were listening to Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side of the Moon.’ Up there was one of the RAF vans, up as far as it could get, with John Foden in all sorts of trouble. He was irritated and he was quite broken. One of the RAF crew was trying to get him to stop and pull out. He would have nothing of it. He was very stubborn. He swore and went around to the back of the van for a bathroom break, came back and said, ‘I’m off,’ and off he went.” Papageorge got back in the car for much needed sleep.

The Second Day

For much of the second day, Papageorge ran with Foden. They ran together in the morning as the sun was coming up and the fog was dissipating. Papageorge said, “Early in the morning, I recall Foden told me the story of Pheidippides meeting the God Pan. I remember talking about it a lot. I was only 18, but remembered that he was eccentric, but very knowledgeable. He knew a lot of stuff. I ran with him for a long, long while.”

The last fifty miles were down through the center of the Peloponnese, where the ground was fairly flat. Foden said, “I ran from Sangas to Tegea on the second morning in considerable heat for about five hours without a drink, because our support vehicle could not find me. I was reduced to a slow walk. In those days the only road to Tripoli and Sparti was via Argos, so our support vehicle had to make a 100 kms detour, during which it lost all contact with us, and we were already causing it trouble by being so spread out.”

Foden did not mind that they were faced with challenges. “In that sense, we were rather pleased that it wasn’t easy, because we thought that it made it much more realistic to what Pheidippides himself would have had to do when he just wouldn’t have been able to carry enough water and food himself to cover the whole distance.”

For the last 50 kilometers, they ran on the road from Tegea to Sparta. Foden had not had enough time before the run to research this section to look for ancient military roads, so they ran on the modern road.

Foden caught up with McCarthy and Papageorge traded off to pace McCarthy. “I ran a little bit with him and then he was in all sorts of trouble. He was really unable to stay awake or run more than a little bit. He was got massaged by the physiotherapist, got back in the car, and tried to sleep for a bit. He was very, very tired. But he was very gritty and continued.”

The Finish

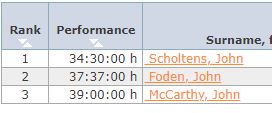

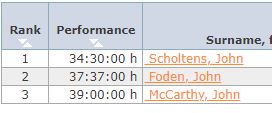

Scholtens was the first to finish, in 34:30. “For Scholtens, there was a rousing cheer from the locals as he entered the sports stadium in Sparta to cross the finish line.”

Foden finished his modern reenactment of the run from Athens to Sparta in the dark at 37:37. The Greeks who cheered him at the finish surprised them with crowns of olive leaves “I just didn’t know what to say. I said, ‘We’ve proved a part of your history is true, the Herodotus was a reliable historian.’”

Papageorge said of Foden, “For me as a kid, when I saw him up on the mountain and his attitude when I was running with him, for him it was not just to prove that the history was true, it was more of a case of winning the day. He was so stubbornly after that.”

Foden insisted in later years that Scholtens had gone off the planned route, taking a ten-mile short cut, helping him to finish first. He claimed that Scholtens had followed a nearly direct course and avoided climb to the pass on Mount Parthenio. In fairness, all the runners got lost, especially Scholtens, and took wrong turns in the towns, so extra miles were experienced by all. McCarthy finished in third, an hour and a half after Foden, in 39:00. He had become lost and ran about seven miles further than Foden. A popular myth that grew out of Foden’s run was that he finished in less that 36 hours, but he did not.

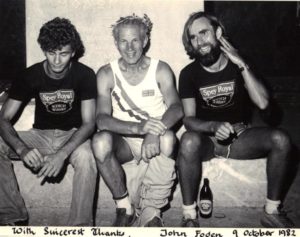

The three runners were thrilled to just sit down to rest on the steps at the foot of the bronze statue of Leonidus at the end of Main Street and just rest. Between the three of them, they had lost a total of 40 pounds. Papageorge paced them for many, many miles of the journey and Foden was deeply grateful for the assistance.

After the Run

Foden told the Greeks around him, “You need to make the route we have run, a race.” But at first, he didn’t seriously think a race would be organized soon. They never dreamed for one moment what a monumental classic like the Spartathlon would grow out of their pioneer run.

The next day, the entire group got together again to take pictures at the statue. John McCarthy was still suffering. Papageorge remembered that Foden stunned his RAF team with a proposal.

Papageorge listened carefully, “Foden said, ‘Let’s walk back to Athens.’ Everyone said, ‘Why, what for?’ He said, ‘That way we can prove that’s what Pheidippides did, because he walked back.’ He said that as a professional messenger, Pheidippides was allowed to eat at any inn or private house, to go in and get their food, water, wine or anything they wanted. Foden said, “We’ve got to prove that this was possible. So, let’s walk back.” Everybody said ‘No, we cannot do it.’ It was a bit strange. I was just a kid, and I could feel the tension. But Foden was quite adamant to do it even without support over three-four days. Fortunately for the whole expedition, they talked him against it.”

The school crew hung out in Sparta during the day, had some dinner and then drove back to Athens. The RAF team later met at the British embassy in Athens and had an awards ceremony, attended by the Campion School teachers. A week later, the five runners ran in the Athens marathon and then returned to Germany. After that they went their various ways and never did hold a reunion. Foden made a report to the RAF on their ‘military exercise.’

Foden’s Later Life

Foden became a driving force in ultrarunning in the UK and an active member of the Road Runners Club. In 1987, Foden organized and was the race director of a 24-hour race held indoors at the Milton Keynes Mall in England. In 1989 his old friend John McCarthy ran there. In 1990 the race was the IAU International 24-hour Championships.

In 1994 Foden was secretary of the Ultra Running Committee of the British Athletic Federation. At the age of 68, he entered an 80-mile World Trail-Running Championship race in Sussex with five hundred others.

Foden ran for the last time in 2000. Later that year he experienced a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. Foden’s wife tragically became disabled as a result of a car crash they were in and passed away in 2001. John Foden died on October 21, 2016, at the age of 90.

The Other Runners

What about the other four who ran in 1982? What happened to them? John Scholtens went on to run London to Brighton twice, in 1983 and 1988, but then quit ultrarunning. He passed away in his early 60s. John McCarthy remained active in ultrarunning through the 1980s, running Spartathlon again in 1985. In 1989 he ran in a 24-hours indoor race at the Milton Keynes Mall in England, reaching 116 miles. Norman Niblock, with his problem knee, did not continue running ultra-distances and passed away in 2015 at the age of 76. Ted Marsh ran London to Brighton in 1975.

Nick Papageorge, the young pacer, graduated from Campion School in Greece the summer after the 1982 run and then went to college in England. He continued running but did not hear about the establishment of the formal Spartathlon for several years. He started running again and did triathlons and then settled in Denmark and worked in Information Technology. He took up ultrarunning in 2012, qualified for Spartathlon by running a 10:22:02 100 km in Copenhagen. He ran in the 2013 Spartathlon but had to stop after 70 km which was very disappointing to him. But he followed that by running 113 miles in a 24-hour race in Spain. Papageorge reflected back, “It was amazing when I think back how privileged we were, all of us, not only the two kids including myself, doing these things out of nowhere, to be part of modern history which is related to ancient history.”

Spartathlon was born! Just as serviceman proved that the Western States course could be covered in less than two days ten years earlier in 1972, servicemen again contributed toward ultrarunning history in 1982 by pioneering Spartathlon.

Next

Just four months after the 1982 RAF Expedition, in February 1983, the Greek Athletic Association announced that a Spartathlon would be held on September 30, 1983. The next episode tells the tale of the first formal Spartathlon in 1983.

Sources:

- Interview with Nick Papageorge, Sep 17, 2021

- Evening Standard (London, England), Aug 7, 1956

- North Wales Weekly News (Denbighshire), Jun 2, 1977

- Lynn Advertiser (King’s Lynn, England), Oct 27, 1981

- Aberdeen Press and Journal (Scotland), Oct 13, 1982

- The Guardian (London, England), Oct 11, 1982, Feb 4, 1983, Jun 24, 1994

- Spartathlon Historical Information

- John Foden documentary – ULTRA

- In the Footsteps of Pheidippides – 1983 footage

- Dean Karnazes, The Road to Sparta

- From the Newsletter of Spartathlon Club of the British Isles 1998/1999

- Australian War Memorial, James Clement Foden

- Spartathlon 30 Years. The footsteps of a Legend

- Peter Krenz, The Battle of Marathon (Yale Library of Military History)