Podcast: Play in new window | Download (36.2MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett and Phil Lowry

You can read, listen, or watch

In Auburn, California, on the evening of July 30, 1972, an awards banquet was held at the fairgrounds for the finishers of the Western States Trail Ride, also known as the Tevis Cup. There was additional excitement that year among the exhausted riders, who early that morning had finished the most famous endurance ride in the world. Not only would the 93 riders receive their finisher belt buckles, but they would witness a trophy awarded to the first person in history to finish the famed trail, not on a horse, but on foot. The special trophy was made and would be presented by the ride’s founder, and president, Wendell Robbie.

In Auburn, California, on the evening of July 30, 1972, an awards banquet was held at the fairgrounds for the finishers of the Western States Trail Ride, also known as the Tevis Cup. There was additional excitement that year among the exhausted riders, who early that morning had finished the most famous endurance ride in the world. Not only would the 93 riders receive their finisher belt buckles, but they would witness a trophy awarded to the first person in history to finish the famed trail, not on a horse, but on foot. The special trophy was made and would be presented by the ride’s founder, and president, Wendell Robbie.

But when the trophy was presented, it was not awarded to Gordy Ainsleigh. His important accomplishment would come two years later. He was not the first to finish Western States on foot, despite the marketing hype you may have been told for 45 years. Ainsleigh was in the audience and watched the trophy and other awards go to the true first finishers. This is the story that has been left out of Western States 100 history.

Note: Also listen to the audio episode for a discussion at the end between the two researchers/authors of this article.

| Learn the true history of Western States 100, including this story in the new books covering the history of the 100-milers. This true story is covered in detail in part two: https://ultrarunninghistory.com/100miles2/ |

Today, where is the trophy for the first finisher on foot? It likely resides forgotten in a dusty storage room in Fort Riley, Kansas, 140 miles west of Kansas City. Perhaps, similar to the depiction in the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark, the trophy will stay hidden for another 50 years. What is the true story behind this “first finisher on foot” trophy, and who received it? It was a front-page story in the Auburn Journal that was later forgotten and buried.

How the First Finisher Story Started

The Western States first finisher story started in 1967 with a young woman named Mary Bradley Lyles (1948-), of Visalia, California. Mary’s father had served in the cavalry in World War II and passed on his passion for horsemanship to his daughters. As teens, Mary and her two sisters, Anne and Peggy became very involved in equestrian events, shows, competitions and weekly training events outside their back door. Their mother would support them by driving horse trailers all over. Mary became a very experienced rider and completed the 1967 Western States Trail Ride at the age of 18. It had been an amazing experience riding day and night across the High Sierra. She married Joseph Thomas McCarthy (1945-) in 1969, who was in the army and soon was sent off to fight the war in Vietnam.

After returning from the war, Capt. McCarthy was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas. He became the leader of an adventure team consisting of many Vietnam veterans still in the service.

As McCarthy was looking for a hard endurance adventure to test his team, his wife, Mary, proposed that the team try to cover the Western States Trail on foot, with the horses, during the Western States Trail Ride that year.

McCarthy loved the idea and received initial approval from Fort Riley post commander, General Edward M. Flanagan, Jr. (1921-2019), who had formed the adventure team, part of the 6th Battalion of the 67th Air Defense Artillery Regiment. Having the team climb over the Sierra for 100 miles in military-issue leather boots and fatigues could be viewed as “fun” for recruiting purposes.

Plans for the March

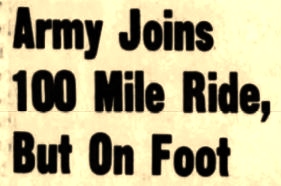

Early in 1972, McCarthy contacted Wendell Robie (1895-1984), the president of the Western States Trail Ride to ask permission for his team to march the trail during the upcoming ride. He explained to Robie, “The Army has a new program of providing its men with challenges that give them an opportunity to see the country. It’s adventure training, providing an incentive challenge, rather than marching in circles.” Robie was thrilled about the idea and had visions that Auburn would someday be the endurance capital of the world. He pledged his support and planned to prepare a “first finisher on foot” trophy. In February, more than five months before the Ride, news went out about the attempt in the Auburn Journal which stated, “we’re sure the troopers will make it to the finish line, or at least to Michigan Bluff.”

At Fort Riley, twenty soldiers were selected by a competition, among fifty volunteers, for the Western States march. Ten others would also be bussed out with them to provide support. McCarthy would be their commander and crew chief, and Lt. Larry Hall would be their march leader. The team trained under the direction of Hall for four months before the historic march by doing five-mile group runs up and down the small Kansas hills, made a few longer hikes, and ran daily. With about three weeks to go they marched 30 miles in six hours in heat that reached 102 degrees and in 96% humidity. But nothing they did in Kansas sufficiently prepared them for what was ahead. At the fort, they were at times referred to as “The New Lewis and Clark Expedition.” The army prepared medals for any who would finish the march.

At Fort Riley, twenty soldiers were selected by a competition, among fifty volunteers, for the Western States march. Ten others would also be bussed out with them to provide support. McCarthy would be their commander and crew chief, and Lt. Larry Hall would be their march leader. The team trained under the direction of Hall for four months before the historic march by doing five-mile group runs up and down the small Kansas hills, made a few longer hikes, and ran daily. With about three weeks to go they marched 30 miles in six hours in heat that reached 102 degrees and in 96% humidity. But nothing they did in Kansas sufficiently prepared them for what was ahead. At the fort, they were at times referred to as “The New Lewis and Clark Expedition.” The army prepared medals for any who would finish the march.

A couple weeks before the historic event, McCarthy and Hall went to California to meet with Robie to plan the march. Robie and Jim Carrier of the Forest Service took the two men to preview the Western States Trail, a historic miner’s trail rediscovered in 1930 by Robert Montgomery Watson (1854-1932) that was initially named “Auburn-Lake Tahoe Riding Trail.” As they went over the map, Robie suggested that they start a day before the ride, which would give them 48 hours to complete the course on foot, well before the awards dinner that would be held that Sunday at 6 p.m. Robie also arranged for an experienced Tevis rider and distance runner, Jim Larimer (1948-2013), his grand son-in-law, to accompany the soldiers with his horse as a guide.

We Aren’t in Kansas Anymore

With two weeks to go, the team completed their training with a 50-mile march. Trained or not, the 20 soldiers and their support staff boarded their bus to California, blowing a fair amount of coin and drinking hard on their last stop in Reno, Nevada, before arriving at Squaw Valley (now called Palisades Tahoe). As they approached the high Sierria, jokes were made that they were not in Kansas anymore. Most of them were cocky that the mountainous march would be no problem, but down deep they were having second thoughts about what lay before them. One of the soldiers who would march said, “We did not expect the terrain to be so difficult.” As he looked up at the mountain peaks, the thought, “This is going to hurt.” Another said, “It was the first time I had been in the western part of the country and the size of the mountains really scared me.”

With two weeks to go, the team completed their training with a 50-mile march. Trained or not, the 20 soldiers and their support staff boarded their bus to California, blowing a fair amount of coin and drinking hard on their last stop in Reno, Nevada, before arriving at Squaw Valley (now called Palisades Tahoe). As they approached the high Sierria, jokes were made that they were not in Kansas anymore. Most of them were cocky that the mountainous march would be no problem, but down deep they were having second thoughts about what lay before them. One of the soldiers who would march said, “We did not expect the terrain to be so difficult.” As he looked up at the mountain peaks, the thought, “This is going to hurt.” Another said, “It was the first time I had been in the western part of the country and the size of the mountains really scared me.”

The soldiers set up a make-shift camp in Squaw Valley and soon many of the more than 170 riders and crews also arrived and filled up the valley, preparing their horses for inspection.

The soldiers set up a make-shift camp in Squaw Valley and soon many of the more than 170 riders and crews also arrived and filled up the valley, preparing their horses for inspection.

The Start

To get a head start on the horses, the twenty soldiers started the day before, on the morning of July 28, 1972, at about 8:30 a.m. A number of curious riders watched the soldiers start. The soldiers, guided by Larimer and his horse, set off to a round of nice cheers. Immediately they faced a 2,500-foot climb to the 8,750-foot Emigrant Pass. Enthusiastic chatter was quickly replaced by labored breathing as they strained to climb in the thin air. Soon the team strung out into separate groups

Their one-quart canteens quickly became low, even though they were supposed to sustain them until the first checkpoint, 20 miles forward. The stragglers began to hold up the team. After the exhausting climb to the Pass, it was easy to see that if they all stayed together, they would never finish, so they broke up into teams of three. Each team could go at their own pace, and the march evolved into a race between the men.

Their one-quart canteens quickly became low, even though they were supposed to sustain them until the first checkpoint, 20 miles forward. The stragglers began to hold up the team. After the exhausting climb to the Pass, it was easy to see that if they all stayed together, they would never finish, so they broke up into teams of three. Each team could go at their own pace, and the march evolved into a race between the men.

The Pinciaro Company

Alan C. Pinciaro (1949-), of Massachusetts, who had just returned from Vietnam, teamed up with two “West Pointers” who had not served in the war. This threesome would march together all day and into the night. One of the West Pointers had complained early and wanted to quit after just one mile. They wore olive drab green military fatigues, military issue leather boots, did not wear packs, and carried no food. They only carried canteens and would use the Western States Trail Ride checkpoints to refill their water and wolf down food. As blisters started to develop, they would change to fresh white military socks, which they carried in their pockets or hung from their pistol belts.

The soldiers continued throughout the day upon the high ridges and down into the hot valleys. During the afternoon as Pinciaro and the West Pointers looked down into a beautiful valley, they were astonished to see a bear down below hunting around looking for food. That made them realize that great caution would be needed because “unfriendlies” could be encountered along the way.

The soldiers continued throughout the day upon the high ridges and down into the hot valleys. During the afternoon as Pinciaro and the West Pointers looked down into a beautiful valley, they were astonished to see a bear down below hunting around looking for food. That made them realize that great caution would be needed because “unfriendlies” could be encountered along the way.

Pinciaro carried three canteens of water with him, but the West Pointers only carried one each. Both soon became empty. Pinciaro bailed them out by sharing his, but before they arrived at the first checkpoint, all their canteens were dry as a bone. The West Pointers continued to complain and talked constantly about quitting. Pinciaro became concerned about the very white lips on one of his companions, covered with salt.

Pinciaro carried three canteens of water with him, but the West Pointers only carried one each. Both soon became empty. Pinciaro bailed them out by sharing his, but before they arrived at the first checkpoint, all their canteens were dry as a bone. The West Pointers continued to complain and talked constantly about quitting. Pinciaro became concerned about the very white lips on one of his companions, covered with salt.

During the afternoon, their leader, Lt. Hall, further ahead, and two others, flagged down a logging truck with a handful of canteens to get them to a water source. By all accounts, the water situation was a constant struggle all day until it cooled down in the evening.

Hall said, “We weren’t expecting a shortage of water at all. We had been told there would be water all along the trail, but a dry spell in the area had dried up the streams.” Sergeant Mike Paduano added, “When I found out we were out of water, I didn’t think anybody would finish the walk. I don’t see how we made it those first 20 miles. I guess it was by watching the scenery that kept me going.”

During the evening as Pinciaro and the two West Pointers neared Robinson Flat (mile 34), they stopped to lay down in a stream to cool themselves off. As they enjoyed the break from the labored march, they heard an alarming loud noise up the stream. With memories of the bear, they had seen earlier in the day, all three sprang up with amazing quickness. Pinciaro recalled that he “had never seen men run so fast.” They ran several hundred yards to get away from there fast, becoming runners – not just marchers. Once they reached Robinson Flat, the West Pointers called it quits, but Pinciaro was still in the game. He went on alone, sometimes catching up with another soldier, but kept to his own pace.

Nine soldiers dropped out at Robinson Flat, “some suffering severe altitude fatigue sickness, some too dehydrated to go on.” Many had run out of water. A couple men had to be taken to the hospital. Their guide Larimer used his horse to take one dropping soldier the rest of the way to the checkpoint. Eleven remaining men, plus Larimer, continued into the night.

The Kruzel Company

Sergeant Kenneth Kruzel (1949-), was teamed up with Specialist Gregory Belgarde (1952-1985), an Alaskan native, and Sergeant David Lenau (1950-). Suddenly Belgarde’s face was covered with gushing blood from a spontaneous and prolific nosebleed. “Hold back your head!” barked Kruzel, willing the blood to stop. Belgarde did his best to stanch the flow. Blood dripped onto his green fatigues and black leather boots. “Just give me a bit,” protested Belgarde. “I need to sit and get this under control.”

Kruzel knew not to leave a buddy behind, but they needed to continue to make progress if they hoped to finish. He replied, “OK Belgarde, Lenau and I will push on. Do what you can.” Belgarde responded, “Roger that. I can fix it.”

A few miles later in darkness, Kruzel and Lenau saw a light approaching from the rear. “Who is that?” murmured Lenau, wondering if his eyes were playing tricks on him. Kruzel squinted, holding up his angle-head flashlight. A figure approached, the chest of his green fatigues covered in blood, his white teeth flashing a grin. It was Belgarde. Kruzel smiled and said, “That’s one tough critter.” Now reunited, the three moved through the night.

Riders catch up to the Soldiers

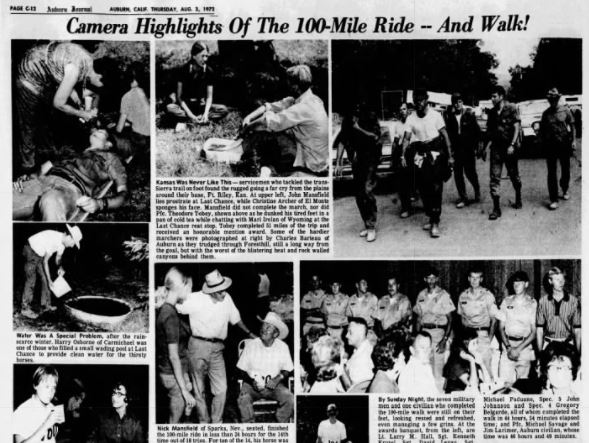

Last Chance (mile 40) was originally planned to be the location for a short sleep stop and several of the soldiers rested, ate, slept, and then continued on after two hours. But others did not stop. One observer stated, “Half the battle was mental attitude. They hypnotized themselves and kept going.”

Specialist Joe Hindley (1949-), of New Jersey, was a talented photographer and artist who was assigned to photograph the historic event. Robie provided him with a vehicle and driver who would take him to each checkpoint to take pictures of the men as they came through. Servicemen from a local Army post also came to the event to serve as the groups’ “crew.” With the soldiers scattered along the trail for miles, it was stressful for the support crew to figure out where they should be to help.

The next afternoon, a group of worn-out soldiers arrived at Michigan Bluff (mile 60). Hal V. Hall (1955-), the leading rider in the endurance ride, and eventual 2nd place finisher, caught up with them.

Hall recalled, “They looked a bit whipped. Their faces were blush-red, they were sweaty, and generally looked tired. They were under a shady tree, most of them seated, and some lying on the ground. Some were shirtless as they filled canteens, and wetted bandanas for their heads.” At this point Larimer, their guide, left his horse Smoke behind and continued the rest of the 60 miles on foot.

Hall recalled, “They looked a bit whipped. Their faces were blush-red, they were sweaty, and generally looked tired. They were under a shady tree, most of them seated, and some lying on the ground. Some were shirtless as they filled canteens, and wetted bandanas for their heads.” At this point Larimer, their guide, left his horse Smoke behind and continued the rest of the 60 miles on foot.

The soldiers continued down the trail, and in the late Saturday afternoon, at about mile 70, were greeted by Rho Bailey on her Arabian horse. Bailey recalled, “They were nice, but at that point didn’t look very much like Military men.”

The Final Miles

At about mile 79, Pinciaro marching alone through his second night, on pace to finish, was the lone soldier at Echo Hills, the 85-mile checkpoint. At each check point, the soldiers were provided food that consisted mostly of freeze-dried Long Range Patrol Rations (LRP), the predecessor for Meals Ready to Eat (MREs). The local servicemen heated up a pot of water for Pinciaro and he dumped a dehydrated LRP Ration in the pot.

But as he began to eat, his sunburn worn-out lips were burned badly by the hot and salty meal. Quickly after that, he fell into a deep sleep. Sadly, no one would wake him up until the morning when it was too late to continue. He was very disappointed that he came so close but did not finish. But he was relieved that his “march of torture” was over and was taken to the local Army post to clean up and rest.

But as he began to eat, his sunburn worn-out lips were burned badly by the hot and salty meal. Quickly after that, he fell into a deep sleep. Sadly, no one would wake him up until the morning when it was too late to continue. He was very disappointed that he came so close but did not finish. But he was relieved that his “march of torture” was over and was taken to the local Army post to clean up and rest.

By mile 85, there were seven remaining soldiers continuing. One of them, PFC Mike Savage, lagged a few miles behind. Riders, including Gordy Ainsleigh, passed by them all night. Lt. Hall said, “We had to stick together towards the end. We needed a collective effort to finish. There were times when one of us would feel like quitting, but the added moral support kept us together.”

The First Finishers

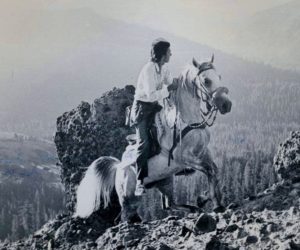

The rhythmic plod, plod, plod of leather boots dominated the sound of that very early Sunday morning, occasionally broken by a barking dog or occasional clip-clopping of a rider passing by with a “Keep it up!” or “Looking good!” The riders shook their heads in disbelief, sympathy, or amazement. After perhaps the longest night of their lives, the soldiers saw lights ahead, the unmistakable finish. The lead six soldiers and Larimer entered McCann Stadium at the Gold Country Fairgrounds.

Hall, the rider who finished many hours before, got up occasionally to walk his horse so it would not stiffen up. He hoped to see the soldiers’ arrival and was awake when they came into the lighted stadium. Cheers went up with congratulations all around. Their finish time was 44:54.

Still out on the trail, Savage made painfully slow progress. All of the horses had passed him, and he was greeted from behind by a rider making sure everyone made it off the course safely. This “sweeper” got off his horse and walked with the limping Savage to the finish. Savage finished in 46:49.

The first to cover the Western States 100 course on foot during the endurance ride were: Larry M. Hall, Michael Paduano (1951-2012), Gregory Belgarde (1952-1985), Kenneth Kruzel (1949-), David E. Lenau (1950-), Jon Johanson, and Michael Savage.

The soldiers’ feat invoked surprise at the finish. “All were tired and footsore, but otherwise in good shape.” One soldier said, “It’s a once in a lifetime thing! I’d never do it again unless I had to, but what a great sense of satisfaction to have finished. I have no regrets that I did it, but I will be damned if I ever do it again.” To a man, none ever did anything like it again. They reveled in their accomplishment but much later looked back on it with a shudder, like many soldiers do when surveying their careers and combat deployments.

Western States First Finishers on Foot

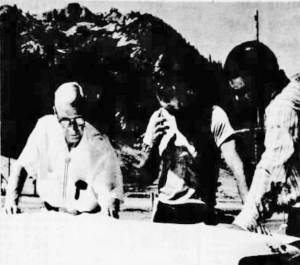

After resting all day, later that night at the awards banquet, the soldiers received a special plaque, recognizing the “First Auburn Endurance March” presented to 1st Lt. Hall by William Penn Mott Jr. (1909-1992), the State Director of Parks and Recreation. The Army awarded additional commendations and medals. The soldiers also received replicas of medals awarded at the Squaw Valley Olympic Games.

It was reported, “Wendell Robie, president of the Western States Trail Ride Association, presented the first six finishers with a collective first finisher on foot trophy. The trophy will be displayed in the battalion’s trophy case.” He said that he hoped another group of soldiers would return next year. The Fort Riley Post stated, “This was the first time the trail had been competitively traveled on foot with a time factor involved.” The soldiers were granted a one-week pass, perhaps their sweetest reward.

Details and pictures of their march appeared in the local newspaper, The Auburn Journal, and in other newspapers across the country. The soldiers eventually returned to Fort Riley and went on with their lives, never to return to Auburn.

The Soldier’s Western State Accomplishment Buried and Forgotten

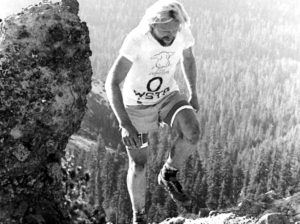

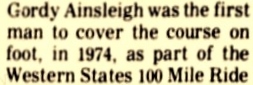

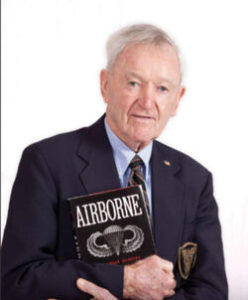

Two years later, in 1974, Gordy Ainsleigh accomplished his run on the Western States Trail, and did it in just under 24 hours. The course was later discovered to be less than 89 miles long. The Western States 100 was established three years later in 1977 by a group of horse endurance riders, including Gordy, under Robie’s direction. Sadly, they purposely buried the accomplishment of the dedicated soldiers and instead propped up a revisionist history, claiming that Ainsleigh was the first to cover the course on foot, and gave him all the credit. Ainsleigh ran with the story and further proclaimed that he invented trail ultrarunning, an obvious falsehood that so many have believed.

Two years later, in 1974, Gordy Ainsleigh accomplished his run on the Western States Trail, and did it in just under 24 hours. The course was later discovered to be less than 89 miles long. The Western States 100 was established three years later in 1977 by a group of horse endurance riders, including Gordy, under Robie’s direction. Sadly, they purposely buried the accomplishment of the dedicated soldiers and instead propped up a revisionist history, claiming that Ainsleigh was the first to cover the course on foot, and gave him all the credit. Ainsleigh ran with the story and further proclaimed that he invented trail ultrarunning, an obvious falsehood that so many have believed.

As the soldiers’ legacy faded, Ainsleigh’s grew. In 1978, the Auburn Journal falsely mentioned that Ainsleigh was “the first man ever to finish the 100-mile course,” and in 1979 hailed him as “the first man to take the course on foot.”

Where Are They Now?

As for the soldiers, most of them left the Army within a few years of the march, losing contact with one another. Some have died.

Ken Kruzel, one of the seven finishers, was 72 years old in 2022, living in Michigan and contributed to this story.

Dave Lenau, one of the first finishers, today reflects on his achievement as he takes walks with his disabled son in the Missouri countryside. He doesn’t really appreciate what he and the others did, which explains much. While it meant a lot to him personally, he was content to allow it to be forgotten.

Greg Belgarde, another finisher, the soldier from Alaska who had the prolific nosebleed, left the service in 1973 and sadly took his own life in 1985 at the age of 32. He is buried in Idaho. When his family was contacted during the research for this story, they were thrilled to learn details of his accomplishment.

Greg Belgarde, another finisher, the soldier from Alaska who had the prolific nosebleed, left the service in 1973 and sadly took his own life in 1985 at the age of 32. He is buried in Idaho. When his family was contacted during the research for this story, they were thrilled to learn details of his accomplishment.

Michael Paduano, also one of the finishers, left the service, went into construction and was an avid New York Giants fan. He settled in Virginia and passed away suddenly and sadly in 2012 at the age of 60. He left behind a wife, two sons and four grandchildren at the time of his death. He had told his son about the march and always said that “it was test of heart, either you wanted it or you didn’t. He also said he just loved the brotherhood of all those who were with him.”

Alan Pinciaro, who wasn’t awakened at mile 85, left the service in 1974 and pursued a career in construction as a truck driver and heavy equipment operator. He now lives in Maine. In 2018, he and his wife had three beautiful daughters, eight grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. When told that someone wanted to talk to him about the march, he searched his memory and started to laugh. He had never heard of the Western States Endurance Run but was thrilled to learn that he was a pioneer of the Run.

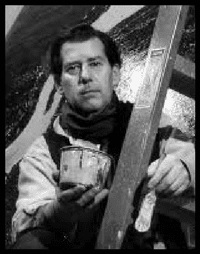

Joe Hindley, who photographed the 1972 event for Fort Riley history, was thrilled to be contacted. He later was selected to the Combat Artist Team working for the Department of Military History in Germany. He went on to be a very accomplished artist, has artwork hanging in the Pentagon, and lives in Michigan.

Joseph McCarthy, the commander and crew chief for the team, in 2022, lived in Laconia, New Hampshire and was 76 years old.

Mary Lyles McCarthy and Joseph had two daughters, one, Laura, was born at Fort Riley, a few months before the march. The McCarthys divorced in 1975. Sadly, their daughter, Laura died in 1985 at the age of thirteen from an equestrian accident. In 2022, Mary is 74 years old and still living in California.

Jim Larimer, of Foresthill California, the soldiers guide, completed eight Tevis Cups and one Western States 100. He was a trail supporter and explorer, who embodied the endurance spirit. Jim was instrumental in developing many trails in the Sierra. He passed away in 2013, at the age of 63, leaving behind a wife and two children.

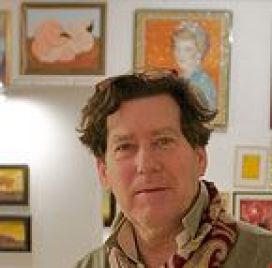

Edward M. Flanagan Jr., the founder of the Fort Riley adventure team, retired from the military in 1978 after 36 years with the rank of Lieutenant General. He went on to author many books and was recognized as the nation’s leading authority on Airborne history. He settled in Beaufort, South Carolina where he died at age of 98 in 2019.

The soldiers of Fort Riley proved that the Western States Trail could be covered on foot in one go. They were the true first finishers of Western States 100. Hopefully now, they will not forgotten and someday will be fully embraced into the carefully crafted Western States Endurance Run’s history. July 30, 2022 will be the 50th anniversary of this historic march. Will Western States honor it?

Will Western States ever honor this history?

The strangeness surrounding acceptance of this history by a very few associated with Western States, despite the facts, is explained toward the end of the article: Western States 100 on Foot – The Forgotten First Finishers in the section “Legacies fade and grow.” The Tevis Ride staff were experienced in putting on 100-mile endurance events and knew better than anyone how to transition to support ultrarunners in 1977 and 1978. Their experience created the cradle into which modern 100-mile trail ultrarunning was born. Putting the March into its proper place in history is not an easy task, or one devoid of passion, but it remains important, just as much as recognizing Wendell Robie for his vision of distance performance.

The Spartathon in Greece was also started by servicemen who attempted the course on foot for the first time in modern times. They are revered and honored in their history. The first known person to run Badwater to Mount Whitney, before the race was established, Albert L. Arnold, was a World War II veteran. He is very honored in Badwater history.

Sadly, a few involved in the early organization of Western States 100 disparage the soldiers because it doesn’t fit the history that they want all of us to believe.

Sources:

- Western States 100 – Legends, Myths, and Folklore

- Western States 100 on Foot – The Forgotten First Finishers

- Gordy Ainsleigh

- Western States 100 – First Year 1977

- Auburn Journal (California), Jul 20, 1972, Aug 3, 1972, Section C, “Camera Highlights of the 100-Mile Ride – And Walk!”, Feb 24, 1972, A-10; Jul 13, 1972, A-10; June 19, 1978, A-8; June 23, 1982, C-1.

- The Press-Tribune (Roseville, California), Jul 26, 1972

- Reno Gazette-Journal, Jul 14, 1972, 5; Jul 31, 1972, 15; Aug 3, 1972, 13

- Fort Riley Post (Kansas), “Seven Air Defenders finish 100-mile hike,” August 11, 1972, 1-2

- 2017 interview with rider, Hal Hall, 30-time finisher and past member of the Western States Trail Foundation.

- 2017 interview with rider, Rho Baily, past member of Board of Governors for the Tevis Cup.

- 2017 interview with Shannon Yewell Weil, original board member of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run and Trustee for 30 years.

- 2017 interview with finisher, Ken Kruzel, soldier

- 2017 interview with finisher, David Lenau, soldier

- 2018 interview with photographer, Joe Hindley, soldier photographer

- 2018 interview with soldier Alan Pinciaro

- 2014 Western States history presentation by Shannon Yewell Weil at the 2014 Western States Training Weekend. This Will Never Catch On: The birth of an Icon

- Results and history of the Tevis Cup (results no longer available online)

- Bill G. Wilson, Challenging the Mountains: The Life and Times of Wendell T. Robie

- Western States 100-mile Endurance run website

- Obituaries for Gregory Belgarde, Jim Larimer, and Edward Flanagan