Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:22 — 27.6MB)

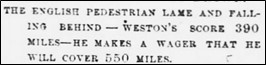

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

The Astley Belt was the most sought-after trophy in ultrarunning or pedestrianism. This race series was recognized as the undisputed international six-day championship of the world. The international six-day race series was established in 1878 by Sir John Astley, a wealthy sportsman and member of the British parliament. Daniel O’Leary won the first two races and then lost the coveted belt to Charles Rowell of England at the Third Astley Belt held in Madison Square Garden during early 1879. Rowell received several challenges for the belt and, by rule, needed to defend the belt again in 1879 and eventually was scheduled in June.

The Astley Belt was the most sought-after trophy in ultrarunning or pedestrianism. This race series was recognized as the undisputed international six-day championship of the world. The international six-day race series was established in 1878 by Sir John Astley, a wealthy sportsman and member of the British parliament. Daniel O’Leary won the first two races and then lost the coveted belt to Charles Rowell of England at the Third Astley Belt held in Madison Square Garden during early 1879. Rowell received several challenges for the belt and, by rule, needed to defend the belt again in 1879 and eventually was scheduled in June.

Making challenges to the belt was costly, requiring a deposit of £100, which today would be the same as depositing nearly $20,000. So, you needed to be very wealthy or must have wealthy backers who wanted to see you enter so they could wager on you. The first ultrarunner to make a formal challenge was American, John Ennis, was one of the first to enter.

Runner Spotlight – John Ennis

John T. Ennis (1842-1929), was a carpenter from Chicago, Illinois. He was born in Richmond Harbor, Longford, Ireland, emigrated to America while young, and served in the Civil War for Illinois. He had been competing in walking since 1868. He beat O’Leary in a handicapped race, early in October 1875, walking 90-miles before O’Leary could reach 100-miles. Additionally, he excelled as an endurance ice-skater. In 1876, he skated for 150 miles in 18:43.

John T. Ennis (1842-1929), was a carpenter from Chicago, Illinois. He was born in Richmond Harbor, Longford, Ireland, emigrated to America while young, and served in the Civil War for Illinois. He had been competing in walking since 1868. He beat O’Leary in a handicapped race, early in October 1875, walking 90-miles before O’Leary could reach 100-miles. Additionally, he excelled as an endurance ice-skater. In 1876, he skated for 150 miles in 18:43.

Ennis was a veteran of several six-day races, but he usually came up short due to stomach problems. Many in Chicago had turned against him. “Is it not about time that this man should end his nonsensical talk? He has made more failures than any known pedestrian in this country.” His pre-race bio included: “John Ennis of Chicago, a remarkable, but unlucky pedestrian, who on several occasions, with victory almost in his grasp, has been forced to leave the track through sickness.”

In 1878, Ennis finally started to taste success. He won a six-day race in Buffalo, New York, but only reached 347 miles. Then he finally had good success walking six days in September 1878, again at Buffalo. He won with 422 miles. The next month, he went to England and raced against Rowell and others in the First English Astley Belt Race where he finished 5th with 410 miles. He finished second in the Third Astley Belt race with 475 miles, winning a fortune of $11,038 ($340,000 value today). He was 5’8” and weight 156 pounds.

Before the Race

Ennis sailed for England on the steamer City of Berlin, on April 20, 1879, to get a full month of training in England before the race. He said, “I never felt better in my life than now.” During the voyage, he planned to walk up and down the decks to keep himself from getting rusty. He would train at the London Athletic Club at Lillie Bridge, Fulham. He said, “The whole of England is against me, I know, and I shall exert myself to perform the greatest feat in my life, and if possible, to bring the Astley Belt back to the United States.” His wife and three children sailed with him, and they arrived in London on May 5th.

Ennis sailed for England on the steamer City of Berlin, on April 20, 1879, to get a full month of training in England before the race. He said, “I never felt better in my life than now.” During the voyage, he planned to walk up and down the decks to keep himself from getting rusty. He would train at the London Athletic Club at Lillie Bridge, Fulham. He said, “The whole of England is against me, I know, and I shall exert myself to perform the greatest feat in my life, and if possible, to bring the Astley Belt back to the United States.” His wife and three children sailed with him, and they arrived in London on May 5th.

The race was postponed for two weeks until June 16th. The defending champion, Rowell, had to pull out of the race because of an abscess on his heel. During some of his final training, the heel was punctured by a peg or small stone that had to be extracted. “Unfortunately, the chief interest in the present competition is lost, owing to the fact of Rowell having at the last moment, broken down.” This was the first time that the Astley Belt holder would not compete to defend the belt.

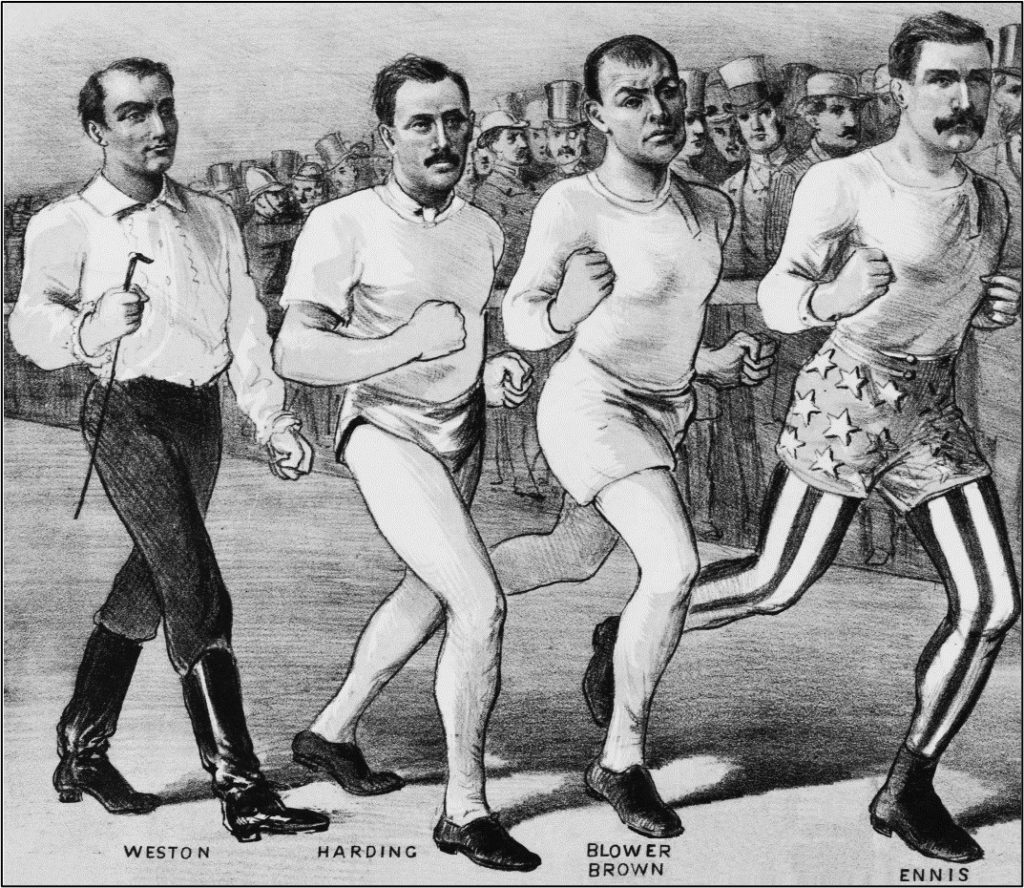

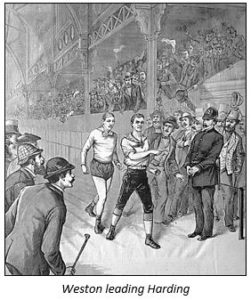

There were four starters, John Ennis, of Chicago, Edward Payson Weston, of Connecticut (but had been in England for three and a half years), Richard “Dick” Harding, of Blackwall, London, and Henry “Blower” Brown, of Fulham, England, holder of the English Astley Belt, and the current six-day world record holder. Their best six-day records were: Ennis, 475, Weston, 510, Harding, no finish, and Brown 542.

Harding was a new six-day runner, backed by the friends of William “Corkey” Gentleman, and was thought to be a genuine competitor. He was best known for competing in minor rowing matches. Brown was the obvious favorite.

Edward Payson Weston

Edward Payson Weston (1839-1929) was the pioneer six-day walker of the Pedestrian era. He was the first person in history to reach 500 miles in six-days. He introduced the six-day race to England in 1876. For months, no British runner could beat him. Eventually, he was beaten by Daniel O’Leary (1846-1933) from Chicago, who went to England to challenge him. Weston stayed in England where he was generally treated well and he won a fortune. However, he lived the highlife and spend his fortune freely, quickly resulting in filing for bankruptcy in England. He also had large debts back in America with aggressive creditors, so he had stayed in England for three and a half years.

As the British considered Weston’s chances in the race, they wrote, “Weston is always to be feared. There is no knowing what may happen should the sun pour down on the glass roof of the Agricultural Hall and raise that building, never famous for ventilation to an almost tropical heat. The heat may prove more trying than any of the competitors have imagined, and under these circumstances, Weston’s chance should not be lost sight of.” During the past 14 years, he claimed that he had walked 53,000 miles.

Weston had asked Astley to back his £100 fee, but Astley tried to discourage him from entering, believing that it would be a waste of money because Weston, a walker, would be no match for a runner. Weston went ahead and entered on his own. He trained hard. He wrote to a friend, “For the first time in my life, I am at present enjoying a severe and strict course of training.” For the first time, he trained to run.

The Start

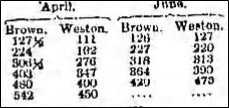

The four competitors were sent on their way at 12:55 a.m., on June 16, 1879. Harding went out fast, followed closely by Brown. Since Weston ran at times, and took fewer rests than the others, he took the lead after 18 hours and made it a close race with Brown. Harding and Ennis were left far behind. At the end of day one, Weston reached 127.3 miles, establishing the third best 24-hour mark in the world and an American record. Brown reached 126.1 miles and Harding was only at 87 miles.

Ennis was even further back, at 70 miles, and had been off of the track for many hours because of terrible stomach and groin pain. A week before the race, he strained his back, plunging into a river near Teddington, England, attempting to rescue some women from drowning after their small boat was capsized when struck by a tugboat. “In performing his plucky action, Ennis struck his head and has not yet recovered from the shock.” He also caught a cold walking in wet clothes back to where he was staying.

Day Two – Brown Breaks 48-Hour World Record

Brown took the lead on the second day and by noon had widened the gap to five miles. It was clear that Weston and Brown were the only contenders in the race. Ennis had nearly recovered from his illness after resting for almost 17 hours and was determined to finish the 450-mile race to win money, despite the low odds and being 83 miles behind Brown.

Brown took the lead on the second day and by noon had widened the gap to five miles. It was clear that Weston and Brown were the only contenders in the race. Ennis had nearly recovered from his illness after resting for almost 17 hours and was determined to finish the 450-mile race to win money, despite the low odds and being 83 miles behind Brown.

At 2:30 p.m., Ennis was the only runner on the track. “Brown soon resumed his journey and started off at a five-miles-an-hour gait, which, as his joints limbered, he increased to six-miles-an-hour. Weston soon followed and was greeted with loud cheers by the Americans, who are beginning to take great interest in the plucky pedestrian. Weston soon settled into a regular six-miles-an-hour trot. Brown and Weston kept together amid loud cheers of their partisans.” Sir John Astley helped to crew Weston, who he had wagers on to win.

At 2:30 p.m., Ennis was the only runner on the track. “Brown soon resumed his journey and started off at a five-miles-an-hour gait, which, as his joints limbered, he increased to six-miles-an-hour. Weston soon followed and was greeted with loud cheers by the Americans, who are beginning to take great interest in the plucky pedestrian. Weston soon settled into a regular six-miles-an-hour trot. Brown and Weston kept together amid loud cheers of their partisans.” Sir John Astley helped to crew Weston, who he had wagers on to win.

Weston, as usual, was vocal about the things that bothered him. “He complains much of the annoyance caused him by people leaning over the rail and smoking, the effect of inhaling the smoke as he runs round being to make him feel sick and giddy.”

Weston, as usual, was vocal about the things that bothered him. “He complains much of the annoyance caused him by people leaning over the rail and smoking, the effect of inhaling the smoke as he runs round being to make him feel sick and giddy.”

In the race’s rear, Ennis reached 100 miles in 37:55:00, and Harding finally reached 100 miles in 39:20:00. During the evening, there were about 2,000 spectators in the hall.

The score at the end of day two (48 hours) was Brown, 225 miles (world record), Weston 218 (American record), Ennis 137, and Harding had been off the track since reaching 109 miles, with badly blistered feet. Brown broke his own 48-hour world record set two months earlier by four miles. “Weston continued on the track, going exceedingly well, considering the great exertion he has undergone, and there will evidently be a severe struggle between the two leaders.”

Day Three – Brown Breaks 72-Hour World Record

Brown remained strong and appeared bright and cheerful during the morning after sunrise. “Weston was somewhat pale and haggard. He had been indisposed during the night, and a physician was summoned to his tent to prescribe remedies.” He had rested nearly two hours more than Brown during the night.

Ennis quit the race at 5:30 p.m. with 180 miles. He later wrote, “I found myself obliged to retire. I felt very sore about it. I had gone a long way to do good work and found myself unable to do any work whatever.”

Harding disappeared for the entire day and eventually quit, with 109 miles. In the evening Weston was eleven miles behind Brown, trying to catch up. “Weston started to do a fast mile and keeping at the double. He did his mile in 8:53, Brown sticking close to his heels all the way. Weston’s progression at this time was simply marvellous, and he appeared as fresh as though he had just started.” At midnight, with one more hour to go, Brown reached 322 miles, which beat his own 72-hour world record of 306 miles. Weston surpassed it too, with 310 miles, for an American record.

Harding disappeared for the entire day and eventually quit, with 109 miles. In the evening Weston was eleven miles behind Brown, trying to catch up. “Weston started to do a fast mile and keeping at the double. He did his mile in 8:53, Brown sticking close to his heels all the way. Weston’s progression at this time was simply marvellous, and he appeared as fresh as though he had just started.” At midnight, with one more hour to go, Brown reached 322 miles, which beat his own 72-hour world record of 306 miles. Weston surpassed it too, with 310 miles, for an American record.

Day Four

From telegraph to America: “The excitement over the walking match, now narrowed down to Brown and Weston, is increasing, and the American competitor is looming up as the probable victor. Brown’s leg is badly affected. It is much swollen and causes him great pain. He limps painfully and is losing ground.”

At 11:30 a.m. on day four, Weston took the lead at 346 miles. In the afternoon, it was reported, “There is great excitement throughout the city. Weston is running. The spectators are cheering, and the band is playing, ‘Coming Through the Rye.’ Weston seemed to be greatly pleased at the enthusiasm shown for him. Many flowers were presented to him.” He later said, “I never believed that running could hold out against walking, but when I saw the pace of some of these runners, I changed my mind. Some of them ran at a ten-mile gait with less apparent exertions than a man makes in walking four miles an hour.”

At 11:30 a.m. on day four, Weston took the lead at 346 miles. In the afternoon, it was reported, “There is great excitement throughout the city. Weston is running. The spectators are cheering, and the band is playing, ‘Coming Through the Rye.’ Weston seemed to be greatly pleased at the enthusiasm shown for him. Many flowers were presented to him.” He later said, “I never believed that running could hold out against walking, but when I saw the pace of some of these runners, I changed my mind. Some of them ran at a ten-mile gait with less apparent exertions than a man makes in walking four miles an hour.”

The pain in Brown’s leg was worsening, leading to severe suffering. After taking a long rest, he emerged with his knee wrapped, trailing behind by eight miles. A doctor came to see him after he reached 360 miles.

Weston set his sights on reaching 550 miles and said this would be his farewell performance in London. Because he had learned how to include running in his six-day efforts, he was surpassing all of his personal records up to this point. Astley visited Weston and made a bet with him that he would not reach 550 miles. If he succeeded, Astley would pay him £500. If he failed, Weston would pay £100. The score after day four stood at: Weston 390 miles, (American record), Brown 364.

Weston set his sights on reaching 550 miles and said this would be his farewell performance in London. Because he had learned how to include running in his six-day efforts, he was surpassing all of his personal records up to this point. Astley visited Weston and made a bet with him that he would not reach 550 miles. If he succeeded, Astley would pay him £500. If he failed, Weston would pay £100. The score after day four stood at: Weston 390 miles, (American record), Brown 364.

Day Five

Weston’s pace slowed on the fifth day. But when the band played, his pace increased to 5 m.p.h. Brown continued to limp along. The attendance was described as “scanty” since it was now evident that Weston would win. Bets were ten to one that he would win and five to one against him reaching 550 miles. The score after day five stood at: Weston 475, Brown 364. Weston needed 67 miles on the final day to break the world record, and eight more to reach 550 miles.

Weston’s pace slowed on the fifth day. But when the band played, his pace increased to 5 m.p.h. Brown continued to limp along. The attendance was described as “scanty” since it was now evident that Weston would win. Bets were ten to one that he would win and five to one against him reaching 550 miles. The score after day five stood at: Weston 475, Brown 364. Weston needed 67 miles on the final day to break the world record, and eight more to reach 550 miles.

The Finish

![]() Weston ran and walked solidly on the last day, which is rather astonishing because he did not have any close competition pushing him. He reached 500 miles in a time of about 131:30:00, about three hours behind Brown’s world record time. “The excitement at the places in London frequented by Americans is at fever heat, but of the best nature. Greetings of ‘Weston is doing nobly,’ ‘He’s ahead of anything yet,’ and similar expressions are to be heard on every hand.”

Weston ran and walked solidly on the last day, which is rather astonishing because he did not have any close competition pushing him. He reached 500 miles in a time of about 131:30:00, about three hours behind Brown’s world record time. “The excitement at the places in London frequented by Americans is at fever heat, but of the best nature. Greetings of ‘Weston is doing nobly,’ ‘He’s ahead of anything yet,’ and similar expressions are to be heard on every hand.”

At 2 p.m., with 507 miles, he boldly proclaimed that he would reach his goal of 550 miles. “The general opinion is that Weston will not accomplish it.” But he was determined and sped up. “Weston was then going as fast, if not faster than the time of any of the contestants in the present match, and he will probably beat Brown’s record. Brown is walking slowly and is merely persevering in order to obtain a share of the gate money.” The current belt holder, Charles Rowell, came during the afternoon to watch and remained until the end.

At 2 p.m., with 507 miles, he boldly proclaimed that he would reach his goal of 550 miles. “The general opinion is that Weston will not accomplish it.” But he was determined and sped up. “Weston was then going as fast, if not faster than the time of any of the contestants in the present match, and he will probably beat Brown’s record. Brown is walking slowly and is merely persevering in order to obtain a share of the gate money.” The current belt holder, Charles Rowell, came during the afternoon to watch and remained until the end.

At 5 p.m. Weston reached 521 miles to Brown’s 448. An hour later, he reached 526 miles after running a 7:37 mile. As news reached America, reporters were convinced that he had no chance to reach 550 miles before the race was to end at 11:00 p.m. At 6 p.m., he had five hours to cover 24 miles to reach 550 miles.

Back in New York City, bulletin boards were set up in hotel corridors that posted updates. Large groups gathered to get the latest news of the race. “As the evening advanced, and the time for receiving the news of the result drew near, the throngs before the bulletin boards grew larger. When the result was known, there was a general rejoicing.”

At 9:30 p.m., Weston broke Brown’s world record of 542 miles in six days. “As his score crept past the greatest ever made, the building fairly shook with tremendous applause of the multitude who watched the sturdy walker, and the change figures on the blackboard. A large number of Americans were present, and their shouts of encouragement and the many bouquets and baskets of beautiful flowers showered upon their plucky countryman, which seemed to infuse him with new life. With a smiling face, he reeled off the laps as though he were walking for the fun of the thing.” His wife, child, and some close friends gathered at his tent for the final hours.

At 9:30 p.m., Weston broke Brown’s world record of 542 miles in six days. “As his score crept past the greatest ever made, the building fairly shook with tremendous applause of the multitude who watched the sturdy walker, and the change figures on the blackboard. A large number of Americans were present, and their shouts of encouragement and the many bouquets and baskets of beautiful flowers showered upon their plucky countryman, which seemed to infuse him with new life. With a smiling face, he reeled off the laps as though he were walking for the fun of the thing.” His wife, child, and some close friends gathered at his tent for the final hours.

Weston went on to reach 550 miles, with five minutes to spare, running his final mile in 11:21. “As Weston passed his tent for the final lap, he was given the British and American flags, which he carried around the ring, waving them amid deafening cheering and music. The band first played, ‘Yankee Doodle,’ and ended with ‘Rule Britannia.’”

Weston set the new six-day world record 550 miles in 142:00:10. He set new American records for all times and distance from 48 hours and beyond. Brown reached 453 miles. About 5,000 people witnessed the finish. Weston won the bet with Astley. In all, he won £1,000 or $5,000 (valued at $155,000 today). It was rumored that an American who helped Weston train for the race won $150,000 betting on him to win (valued at $4.6 million today) and Weston was given half of those winnings. To those in the sport, he showed that the world record could go much higher.

The Astley belt would be heading back to America and Charles Rowell immediately issued a challenge to get it back and deposited the challenge fee of £100 with The Sportsman. Two days later, Weston returned to the Agricultural Hall with Astley and others to deliver a farewell address before his departure for America. He took his time returning, going on a speaking tour in England entitled, “What I Know About Walking.” He would return to America three months later, in September 1879, to get ready for the next Astley Belt race.

Reaction Back in America

The newspapers celebrated Weston’s accomplishment and called him “The father of long-distance pedestrianism.” Indeed, this was Weston’s greatest pedestrian accomplishment of his life. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote, “After a series of pedestrian failures, which had rendered him a byword for promising to do more than he could perform, Mr. E. P. Weston has at length accomplished a feat unparalleled in these days of walking matches. That he, of all Americans, should have been the champion to bring back the coveted emblem of pedestrian superiority is a surprise. Weston has done his best, without any doubt.”

The newspapers celebrated Weston’s accomplishment and called him “The father of long-distance pedestrianism.” Indeed, this was Weston’s greatest pedestrian accomplishment of his life. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote, “After a series of pedestrian failures, which had rendered him a byword for promising to do more than he could perform, Mr. E. P. Weston has at length accomplished a feat unparalleled in these days of walking matches. That he, of all Americans, should have been the champion to bring back the coveted emblem of pedestrian superiority is a surprise. Weston has done his best, without any doubt.”

Daniel O’Leary, Weston’s former rival, was suspicious. “He said that Sir John Astley would come to New York in the fall, with four or five of his crack walkers and runners, and not only take the belt, but the enormous pile of gate money which would undoubtedly flow into the box-office. Rowell was kept out of the race to save him for the contest in September (the Fifth Astley Belt)” He believed Weston had many British friends after being there for three and a half years and was in cahoots with them.

Boston wrote, “Six-day matches repeated twice or thrice a year cannot be beneficial either to the mind or body. An exhibition of suffering such as were made at Madison Square Garden, ought to be fit subjects of police interference.”

Ennis gave Weston a lot of credit and wrote, “For the first time in his life, he gave himself a fair show. For the first time since I have known him, he went on the track to win and not to win the admiration of the ladies. He discarded his frilled shirt, his fancy sash, and the other trumperies which have generally distinguished him on the track. He was dressed to walk, and not simply to make a show of himself, and he did walk, and he won the belt.” He also said the Brown tried to follow closely on Weston’s heels, dogging him. “Weston saw the game, and he was equal to the emergency. It is a great trick of his to reverse in walking, that is, to turn around and walk in the opposite direction. He practiced this to Brown’s disaster. He knew just when he was going to reverse, but Brown did not.”

British Reaction

The Brits thought Weston was lucky. “It was fortunate for the prospects of the Americans that Blower Brown broke down at such a critical moment of the race, otherwise Weston would have had a hard time of it.” They also admitted, “The sparseness of public attendance during the week proves that the English people are getting somewhat tired of the increasing number of these monotonous competitions.”

They also saw a silver lining. “It was Weston’s last performance in England, and there is therefore room for the hope that the meaningless wearisome feats of endurance which he introduced here may not long survive the departure of their chief exponent.” They claimed that the applause was “fitful and infrequent” during the last evening, “and only really rose to anything mildly resembling enthusiasm during the last mile or two of Weston’s long journey.”

Sources:

- The Buffalo Commercial (New York), Apr 21, May 28, 1879

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), May 1, 1879

- Aberdeen Journal (Scotland), Jun 17, 1879

- The Yorkshire Herald (North Yorkshire, England), Jun 16, 1879

- The Citizen (Gloucester, England), Jun 17, 1879

- Evening Post (Nottingham, England), Jun 18, 23, 1879

- Daily News (London, England), Jun 18, 19, 1879

- The Times (London, England), Jun 18, 1879

- The Sun (London, England), Jun 18, 20, 22, 1879

- Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), Jun 19, 21, 1879

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Jun 19, 21, 1879

- Buffalo Courier (New York), Jun 20, 1879

- The New York Times (New York), Jun 20, 22, July 27, 1879

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), Jun 21, 22, 1879

- The Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Jun 23, 1879

- Poughkeepsie Eagle News (New York), Jun 23, 1879

- The Morning Post (London, England), Jun 23, 1879

- The Yorkshire Herald (North Yorkshire), Jun 23, 1879